Of Milk Cows and Saudi Arabia

Posted by JoulesBurn on September 10, 2013 - 9:59am

Under the desert in eastern Saudi Arabia lies Ghawar, the largest oil field in the world. It has been famously productive, with a per-well flow rate of thousands of barrels per day, owing to a combination of efficient water injection, good rock permeability, and other factors. At its best, it set the standard for easy oil. The first wells were drilled with rather rudimentary equipment hauled across the desert sands, and the oil would flow out at ten thousand barrels per day. It was, in a sense, a giant udder. And the world milked it hard for awhile.

Under the desert in eastern Saudi Arabia lies Ghawar, the largest oil field in the world. It has been famously productive, with a per-well flow rate of thousands of barrels per day, owing to a combination of efficient water injection, good rock permeability, and other factors. At its best, it set the standard for easy oil. The first wells were drilled with rather rudimentary equipment hauled across the desert sands, and the oil would flow out at ten thousand barrels per day. It was, in a sense, a giant udder. And the world milked it hard for awhile.

However, this article isn't just about a metaphor; it is also about cows, the Holsteins of Haradh. But in the end, I will circle back to the present and future of Saudi oil production.

In my Google Earth-enabled virtual travels around Saudi Arabia looking for oil wells and such, I have come upon many strange sights. Some of these are of natural origin yet can only be appreciated from a satellite's perspective, as is the case for this tidal pool located near a gas oil separation plant for the Safaniya oil field:

| ||

| Figure 1. My favorite Google Earth view, near Safaniyah oil field, Saudi Arabia |

There are many crop circles scattered about eastern Saudi Arabia -- by which I mean circles of crops watered by central pivot irrigation (as opposed to circles of crops flattened by aliens). A line of such circles cuts across the southern tip of the Ghawar field, seemingly following the course of a dry river bed.

| ||

| Figure 2. Irrigation along the southern fringe of the Ghawar Oil Field, Saudi Arabia. Arrows indicate location of features of interest. |

Located on this line, just to the west of the field periphery, are three rather symmetrical structures:

| ||

| Figure 3. Symmetrical objects of interest near Ghawar oil field. |

Each of these is about 250 meters in radius. It took me awhile to discover what these were, as at the time, crowdsourced mapping was just getting started. It so happens that they are part of a huge integrated dairy operation, one of the largest in the world. Fodder crops are grown in nearby circles, cows are milked with state of the art equipment, and the milk is packaged and/or processed into cheese and other products before being shipped. All of this happens in the northernmost fringe of the Rub' al Khali desert, one of the most inhospitable places on earth. Start here to browse around Saudi Arabia's Dairyland on your own using Google Maps.

Turning Black Gold Into White Milk

Here is a glossy PR video describing the operations:

Although the original intent was to locally breed cows more suited to the Saudi climate, it seems they had to import them. Here is another video describing the transport of cows from Australia. A bit different than a Texas cattle drive.

They Built It, But They Didn't Come

Answering why and how these dairy farms came to be located here reveals some interesting history of Saudi Arabia. Although great wealth of the country results from its abundant store of fossil fuels, the necessity of diversifying the economy has long been recognized. The lack of food security was always a big concern. In addition, there remained the nagging problem of what to do with the Bedouins, nomadic peoples who resisted efforts to be integrated into the broader Saudi society. And since they now had it in abundance, they decided to throw money at the problems. What could go wrong?

As related in the book "Inside the Mirage" by Thomas Lippman, a problem with Saudi agriculture is that most of the private land was owned by just a few people, and they were wealthy aristocrats, not farmers, and there wasn't much local knowledge of modern large-scale agriculture in any case. One of the proposed solutions was to create huge demonstration projects by which modern techniques of farming could be learned and applied. As for labor, the goal was to provide individual farms, housing, and modern conveniences to the Bedouin, who would settle down for a life on the farm. The largest such project was the al-Faysal Settlement Project at Haradh, designed for 1000 families. It didn't work out as planned, though, because the Bedouins never came:

You know of the Haradh project, where $20 million was spent irrigating a spot in the desert where an aquifer was found not too far from the surface. This project took six years to complete and was done for the purpose of settling Bedouin tribes. At the end of six years, no Bedouin turned up and the government had to consider how to use the most modern desert irrigation facility in the world.

(From a 1974 Ford Foundation memo)

Eventually, the Saudi government partnered with Masstock, a Dublin-based industrialized endeavor run by two brothers. The Haradh project became the largest of their operations in Saudi Arabia at the time. Eventually, a new company called Almarai (Arabic for "pasture") was created which involved Prince Sultan bin Mohammed bin Saud Al Kabeer. In 1981, a royal decree created the National Agricultural Development Company (NADEC) for the purpose of furthering agricultural independence, and (for reasons I haven't discerned), NADEC gained control of the Haradh project. Almarai went on the become the largest vertically integrated dairy company in the world, and Al Kabeer is a hidden billionaire.

As a side note, NADEC sued Saudi Aramco a few years ago as a result of the latter using some NADEC property for Haradh oil operations, and a lower court ordered Saudi Aramco to vacate. The web links to those reports have disappeared, and one wonders how the appeal went. Separately, NADEC has reportedly obtained farmland in Sudan. Food security.

Speaking of Cash Cows

A half decade ago, much of The Oil Drum's focus was on possible problems with Saudi Arabian oil production. Was the flow from Ghawar tanking? Were all of their older fields well past their prime, and were their future options as limited as Matt Simmons suggested in Twilight in the Desert? My analyses and those of others here seem to suggest a rather aggressive effort to stem decline. With further hindsight, it is clear that Saudi Aramco was caught a bit off guard by decline in existing production. But over time, they were able to complete several decline mitigation projects as well as many so-called mega-projects with many million barrels per day of new production. With each project, the technological sophistication has grown - along with the expense. The Khurais redevelopment, which is reportedly producing as expected, features centralized facilities for oil, gas, and injection water processing. Water goes out, and oil comes back.

|

| |

| Figure 4. Left: map showing Saudi oil fields, Right: Khurais Project pipeline network (source: Snowden's laptop) | ||

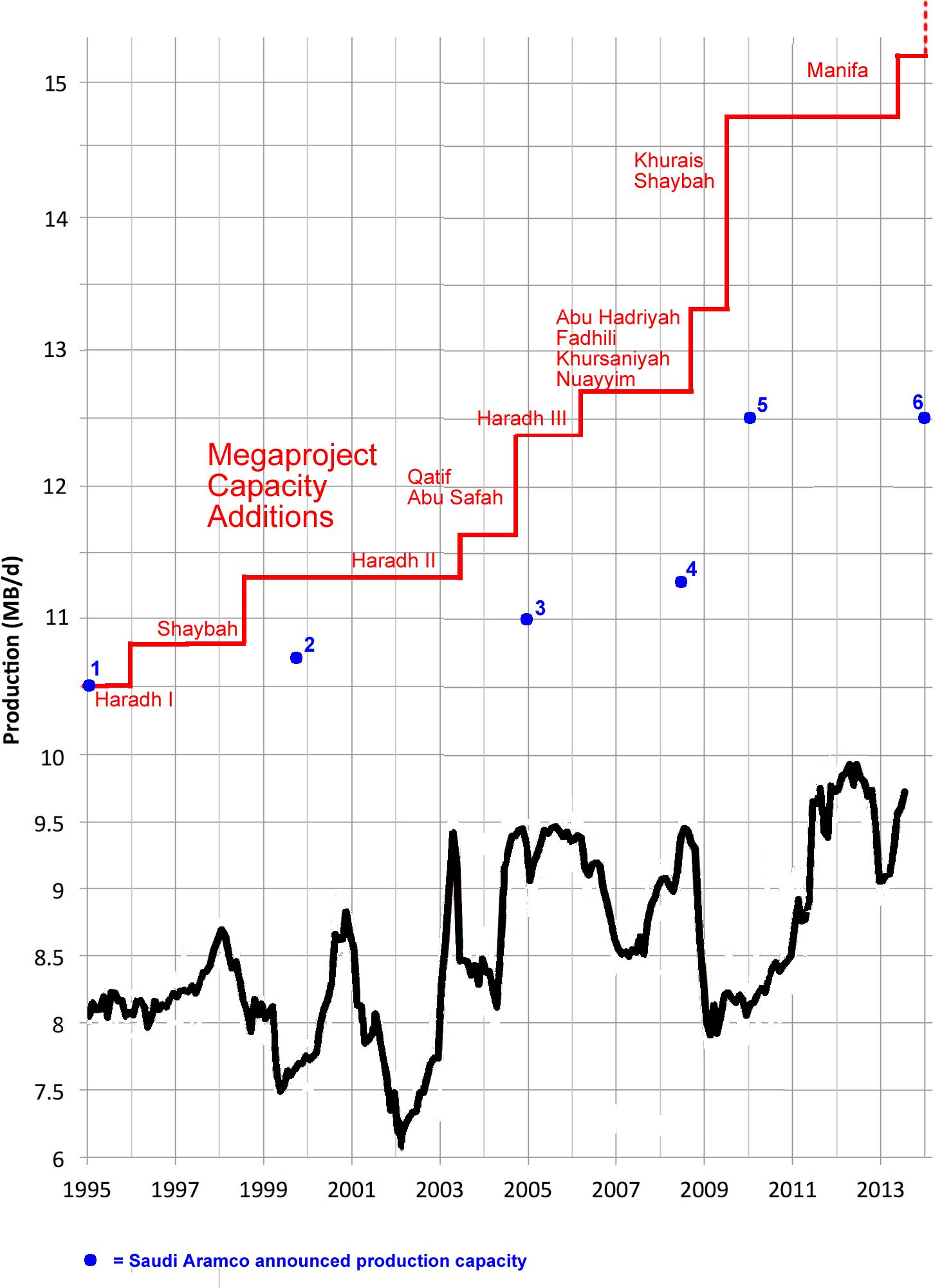

The most recent project, the Manifa field redevelopment is a logistical marvel. These have so far proven to be very successful projects (even though Manifa is not fully completed). But if one looks for the impact of the projects on their total output, one comes back somewhat underwhelmed. In the following graphic I show Saudi Arabian production with the theoretical (zero depletion) and official (as reported directly by Saudi Aramco) production capacities.

|

| Figure 5. Saudi Arabian crude oil production increases from megaprojects since 1996, compared with actual crude production (source: Stuart Staniford). Cumulative increases are superimposed on the Saudi Aramco reported baseline value of 10.5 mbpd capacity in 1995. Blue dots denote values obtained from references 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 |

Here are some conclusions one might draw from the above (including the references):

- Saudi Aramco has generally been self-consistent when reporting spare capacity and total capacity in light of actual production

- Production capacity increased subsequent to startup of megaprojects. However, the net production capacity increases were uniformly and substantially less than the planned increments. In total, 5 million barrels per day of production was added, but capacity increased by only 2 mbpd.

- It is most unlikely that reported production capacities accurately reflected what was producible at any point in time, given the reported values as correlated with the timing of the increases from the megaprojects.

- However, actual production did not generally increase immediately after projects were completed, indicating that production capacity was not completely exhausted beforehand. But there was certainly an impetus to add a lot of production quickly.

The gap between what might have been (red staircase) and what is reported as production capacity (blue dots) is explained by considering the net of two competing developments: 1) depletion of legacy fields (Ghawar etc.) as they are produced, and b) mitigation of this depletion by drilling new wells in these fields. Since Saudi Aramco does not release data for individual fields or new vs. old wells, we are left to speculate on the relative magnitudes of these. On the plus side, the 5 mbpd from the new projects will (hopefully) deplete less rapidly than older fields. On the minus side, only 2 mbpd capacity was added - and they have exhausted all of the major fields in the pipeline. On the double minus side (for the world, anyway), only 1 - 1.5 mbpd of actual production was added since 1995, and (according to BP) all of that increase went into internal consumption. So after nearly 20 years, though total world crude production (and population) has increased, Saudi Arabia exports the same amount of oil as before. And yet, there is still a lot of hydrocarbons under Saudi Arabia. And it seems they already realize the need for more, as there are reports of planned increases from Khurais and Shaybah totaling 550 kbpd by 2017 to "take the strain off Ghawar". I feel its pain.

Addendum: According to this news report, oil has not actually flowed yet from Manifa. The new Jubail refinery has reportedly no received any Manifa oil as of yet:

The refinery is configured to run on heavy crude oil. But two industry sources said the refinery had not received any of the heavy crude expected from Aramco's new Manifa field and that it was running instead on light crude. Aramco said in April that it had started production at Manifa.-Reuters

Still the One?

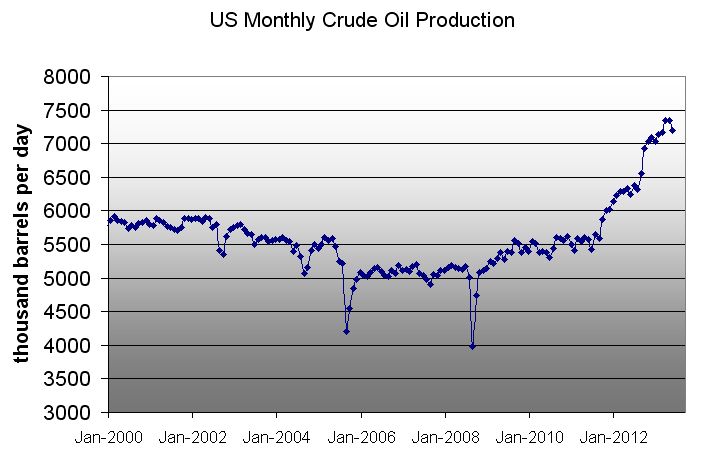

Despite all of the negativity emitted above, it is also evident that Saudi Arabia has had and will continue to have a role as the primary provider of spare capacity which can be deployed to buffer variability in world demand. It can do this because Saudi Aramco, the largest oil company in the world, can effect oil prices by virtue of what it can put on or take off the world market. Contrast the Saudi production profile with that of the United States, shown below.

|

| Figure 6. United States monthly crude oil production (source: EIA) |

Aside from some minor month-to-month fluctuations and some notable downward spikes caused by Gulf of Mexico hurricanes in 2002 (Isadore), 2004 (Ivan), 2005 (Katrina and Rita), and 2008 (Gustav), production follows a smooth trend. Especially noteworthy is the contrast between Saudi and US production subsequent to the economic downturn in 2008, when oil prices collapsed: Saudi Arabia throttled back while the US kept pumping. Any individual producer in the US had little incentive to hold back oil. However, with the increased importance of Shale plays (Bakken and Eagle Ford) to US production, this might change the dynamics going forward. Since these wells deplete rapidly, any decrease in drilling caused by low prices will also throttle demand (although with a time lag).

The Hungry Cow

The other new "above ground factor" is the problem of growing internal consumption in Saudi Arabia, of just about everyting including oil. To air condition all of those cows, it takes a lot of electricity (and currently oil). And all of that milk feeds a growing, young population. But that milk is bound to get more expensive, since the aquifers from which those massive dairy operations get their water are being rapidly depleted.

Milk consumption in Saudi Arabia reached 729.4 million litres in 2012

...

The Kingdom has already depleted 70% of these sources of water and must now turn increasingly to desalinisation which when factored into the cost of producing fresh milk is very expensive. Experts have estimated that it takes between 500- 1000 litres of fresh water to produce 1 litre of fresh milk if one takes into around the irrigation required to grow the Rhodes grass or Alfalfa required to feed the cows.

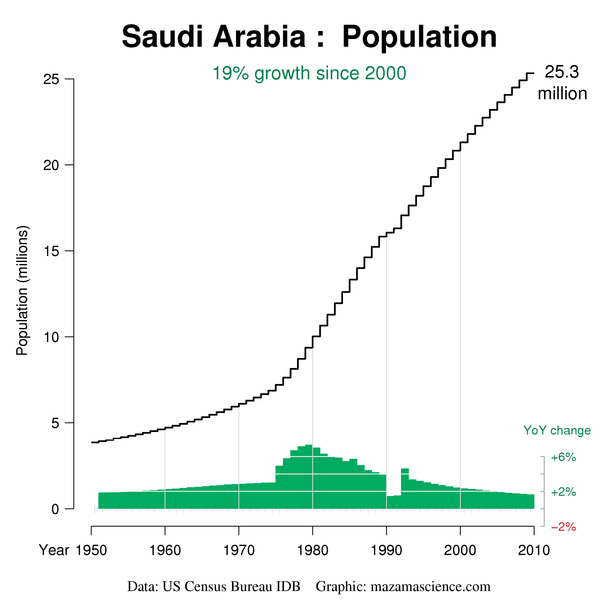

It seems Saudi Arabia has cash flow problems, although it is hard to imagine why, given that they are currently producing as much oil as ever at $100/barrel. For one thing, their population keeps growing:

|

| Figure 7. Saudi Arabia population growth (source: Thanks, Jonathan!) |

and they need to spread around some money to maintain political stability. Their energy use is out of control, as is their water consumption. And for those segments of Saudi society into which much of the oil revenue flows, consumption is a happening thing. And nobody really knows where the all money goes.

Saudi Aramco is overseen by the Petroleum and Mineral Resources Ministry and, to a lesser extent, the Supreme Petroleum Council, an executive body. The company pays royalties and dividends to the state and supplies domestic refineries. Revenues go to the Finance Ministry, but the amounts are not published. There is no transparency in the national budgeting process, and it is unclear how oil revenues are used. Environmental impact assessments are required, but the results are not made public. Laws and decrees concerning the extractive industries are published and include guidelines for the licensing process in sectors other than upstream oil, but do not contain details on fiscal arrangements. Saudi Arabia has no freedom of information law.

Some ends up in London, where some Saudi tourists spend the entire summer. Of course, this was true in 2002 (and oil was $26/barrel then).

But they do seem to have money to throw around to garner political influence (note that the US does the same with money that it doesn't have). And they have grand plans for looking beyond their petro-heritage:

Best hopes for wise spending.

Au revoir. Au lait.

Fascinating story of the dairy in the desert. It's new to me. Those irrigated circles are in the 50-90 acre range each. I wonder how much water they collectively use and how long it's going to last? But it's an impressively large modern industrial farming and production setup, judging by the video. Amazing that it's in the middle of such an arid area.

The Saudis are buying land in South Africa. Not for farming, but for hunting our local bustards with falcons.

Thanks for reminding me to add something on that. See in the main post, just below the "Hungry Cow" heading. A thousand liters of fossil water for every liter of milk. And desalination is a costly alternative. Assume that desal costs are $1 per cubic meter of water:

https://www.fnu.zmaw.de/fileadmin/fnu-files/publication/working-papers/D...

This would add $1/liter to the cost of the milk.

There are occasional references in the agricultural press about such desert farms but I haven't followed up on them.

Anybody who is interested in this economic farce farming could probably find out a lot if he were to spend a few hours looking.

It's common knowledge that the Saudis wasted billions trying to grow irrigated wheat before they gave up in the face of aquifer depletion.

I have remarked here before that vertical farming is a pipe dream for economic reasons even though the technical problems can be easily solved by throwing ENOUGH money at them.

The lack of light for instance could be remedied with grow lights in the shaded interior portions of a vertical farm, and the problem of the vertical farmer being sued for blocking the sun from neighboring properties could be settled with lawsuits and purchases of any adjacent properties deprived of sunlight.

I guess if the Saudis can afford this sort of dairy farm, they can afford to convert or build high rise buildings to grow veggies too. sarc

Someday about 99 percent of them are going to either either emigrate or starve unless they are able to either build out a huge nuclear energy capability or a equally huge solar capacity, or some of both.

What is the current status of nuclear desalinization in Saudi Arabia? Are there still plans for future plants?

In the link I provided, it is said they hope to have 2 reactors in 10 years, then adding 2 every year until 2030.

There are a number of examples of solar greenhouses that desalinate and grow crops.

see this: http://www.sundropfarms.com/

The issue is access to seawater which may require piping a considerable distance as well as a return for the hyper-saline effluent.

I would expect that the components could be sized to produce excess fresh water and electricity.

As the oil output decreases, KSA could use the seawater pipeline infrastructure to Ghawar and Khurais as a source for the wate requirements. My understanding of the Sundrop Farms technology (in discussion with the founder creator of the technology, Charlie Paton) is that there is very little effluent per se, just a large amount of salt (which of course has uses...).

In terms of the electricity requirements for these dairy farms, the huge amount of roof space would lend itself well to PV.... or, even better, PV-T (hybrid PV / solar thermal panels) where the hot water produced could be used for washing down and would enable greater electrical output from the panels by allowing them to operate at a lower temperature than conventional PV.

First of all, the water requirements for Ghawar etc. are actually rather modest compared to what is currently being done with desalination (drinking water). But more to the point, the reason that those dairies are there is because of the aquifer. It would make more sense to move them closer to the sea.

Are we getting into geoengineering here? Getting all a bit sci fi.

My company bought 4300 acres of cropland with great water rights in the Delta region of CA. A major competitor was a company that specializes in export of alfalfa hay for Saudi dairies. So, they are not just looking to Africa for food security, but right in the heart of the most production agricultural and populous state in the US.

Interesting Jason. But importing hay from California to feed dairy cows in Saudi Arabia doesn't scream "food security". I think the only reason this is happening is that certain royals have a stake in the dairies.

Thank you Joules. I really have missed posts like these, not many from anybody the last couple years.

As for the US throwing around money it doesn't have, well that's out there in the realm of finance where quantum foam is in the realm of physics. If I understand the concept more or less correctly that foam is essentially the matter that 'isn't there' at the moment of measurement but it accounts for something like 30% of the mass of the matter which 'is there' right then (we are talking the visuable measureable stuff here not even touching on the dark stuff). We are well beyond simple measurements and straight line flows when we get out into these realms.

I wouldn't be too concerned with Saudi population growth. Seems the young population has already figured out ways to slow it down by speeding up!

Tom Murphy has a great post on population and energy over on his Do The Math site: http://physics.ucsd.edu/do-the-math/2013/09/the-real-population-problem/

And there's this effort from TeD with a Middle East focus and excellent graphics by demographer Hans Rosling: http://www.ted.com/talks/hans_rosling_religions_and_babies.html

Hint: it's not about religion but about women's education

I believe the Fremen do exist in vast numbers

Yet the point of perhaps the most interest to Murphy, the outlier status of Qatar in the population growth and income stakes, completely contradicts what Rosling is saying (at TEDx Doha, Qatar!), that even Qataris have settled down to two-child families like almost everyone else.

The nations "above and to the right of Germany" with high income and positive population growth are destinations for economic migration. The world, as a whole, is not and cannot be. World population growth is births minus deaths, alone. What happens to births to migrants when they arrive in a high-income country? What happens when high incomes reach poor, rapid-growth, migrant source nations (such as Ireland, Mr Murphy), or when a country's per capita income reaches the world median income?

To appreciate population effects on the world as a whole we should look not at national population growth rates but at the global one. It is trending down as per capita energy consumption (and income in real terms) trend up.

http://www.google.com.au/publicdata/explore?ds=d5bncppjof8f9_&ctype=l&me...

This is the kind of article that got me hooked on TOD six or seven years ago. Great stuff!

I keep thinking lately about the difference between SA and Mexico. Here you have two countries with similar legal structures for their oil wealth. One seems to do everything right in developing and managing their oil and the other seems to do nothing right.

Interesting question. There are so many variables/differences, including the relationship with foreign service providers (Haliburton et. al.), the fact that the transition from Aramco to Saudi Aramco was rather smooth, and expats still have a strong hand in running it. Mexico's population is much larger, and their oil bounty smaller. Ghawar vs. Cantarell. Petrobras would be another comparison, though I know little about that company as well.

Excellent article. In fact, it was udderly fascinating. ;)

How long can they keep this up? You say:

"Despite all of the negativity emitted above, it is also evident that Saudi Arabia has had and will continue to have a role as the primary provider of spare capacity which can be deployed to buffer variability in world demand."

What if some of the larger and older fields start to decline much faster than anticipated and the newer ones don't produce as much as expected? Isn't that a real possibility?

I honestly don't know. The only thing that I can say is that some 3 mbpd is no longer being produced by the older fields as compared to a dozen years ago. They have since put a lot of money in north and central Ghawar, Safaniyah, Berri, Abqaiq (still!), Zuluf, Marjan, etc., and there is a limit to what more money will do. But the uncertainty is asymmetrical. I don't think the world is going to get any more oil per day from KSA than they do right now. Perhaps less, but I don't know over what time this will happen.

As for the new ones not producing: as the oil is there, they will find a way. They have a ways to go before they reach Bakken-level or Athabasca-level extraction costs.

I understand, while there is a danger in being a Pollyanna when it comes to problems with oil depletion. It is also a problem yelling the sky is falling all the time. It seems that we will start to see when we have peaked in oil production and are on the downslide. The only problem is that with human nature when hording occurs people tend not to say how many eggs are in their basket for fear of losing them. SA seemed to be nervous initially about US shale deposits but have since backed off. I was surprised to read how many people here have stated that they think the main problems are 20 years off into the future. I was thinking they were about 3 years into the future! When the Bakaan and Eagle Ford start showing signs of aging and it is too hard for the media to cover up the stories.

It's not that far off. Their costs must be approaching shale oil or oil sands levels as they try desperately to keep their old oil fields running while trying to bring new and much more difficult fields on line. They don't have the free-enterprise system to keep their costs down, or a highly educated population of people who are willing to get their hands dirty and work long, hard hours under difficult conditions to eke out those last barrels of oil.

Saudi Arabia is the poster child for unsustainable development. It is basically a desert wasteland with a few oases and very little agricultural potential, whose only important assets are oil and religion. At the same time as its oil reserves are starting to decline, its population is growing very fast. It has nearly 30 million people now, almost as many as Canada, compared to about 4 million in 1960 when its oil production really started growing. By the time it runs out of oil completely, it will probably have more people than Canada or California. This will not be a good experience for its people. Religious fervor will not keep them fed.

A last kick at the can before TOD shuts down completely.

I'm working on updating, with 2012 annual data, my paper on what I call the Export Capacity Index (ECI*). Here is a chart showing the 2005 to 2012 rates of change in the ECI ratios, by country for the (2005) Top 33 net oil exporters:

Based on the 2005 to 2012 data, about four-fifths of the top 33 net oil exporters in 2005 were trending toward zero net oil exports.

Note that even if an oil exporting country is showing increasing production, if their consumption is rising faster than production, their ECI ratio is declining, and they are headed toward zero net oil exports, which is why the US and China both became net importers, prior to production peaks.

In any case, based on the 2005 to 2012 data, I estimate that Saudi Arabia may have shipped about half of their post-2005 CNE (Cumulative Net Exports) by the end of 2017, four years hence. Note that a similar extrapolation for my Six Country Case History produced a post-1995 CNE estimate that was too optimistic.

*ECI = Ratio of total petroleum liquids + other liquids production divided by liquids consumption (EIA)

WT - where will you post such things post-TOD? Graphoilogy? Looks like the latest post there is over a year old... Will you be updating there, or elsewhere? Thanks! And thanks for beating your drum so relentlessly all these years - ELM & ELP are no longer a tree and a band to those of us around here...

I'll primarily be on the ASPO-USA website, with articles usually also posted on PeakOilBarrel and on the Resilience website.

I've actually been having some interesting discussions with a senior EIA analyst regarding "Net Export Math," following a meeting last year with senior EIA and DOE personnel (part of a contingent from ASPO-USA, including Art Berman and Tad Patzek). My hope is that they start modeling future global net exports based on the assumptions of varying rates of increase in domestic consumption in oil exporting countries.

"My hope is that they start modeling future global net exports based on the assumptions of varying rates of increase in domestic consumption in oil exporting countries.

Since the surest way to ensure continuing levels of exports from these countries, long term, is to destroy or limit their ability to consume those resources themselves, I'm just curious as to what your motivation is in bringing this information to the attention of TPTB. Please don't take this the wrong way, but it occurs to me that this is as likely a response as any. Then, again, if the US and its western allies don't do it, China probably will.

Just askin': Why bother?

"If a Path to the Better There Be, It Begins With a Full Look at the Worst."

If TOD wasn't going out of business, I would like to an article entitled milk cows and arizona, and how it is any different. Like the rest of the western states, 75% of arizona's water goes to agriculture.

How much goes to golf courses? There seems to be a lot of those around Phoenix, which is where I presently find myself.

4%-5% of Phoenix water goes to golf courses. A majority of Tucson area courses use reclaimed water. Some courses have water rights dating from when the Apache roam this area and can drain our aquifers cheaper than drawing municipal water. Tucson has reached peak golf. The city of Tucson has five golf courses that don't pay for themselves that they are trying to do something with. Private golf course owners are struggling too but its harder to get straight numbers from privately held firms. The water bill on a golf course can exceed a quarter mil per year.

Robert a Tucson

The people of Arizona have forty nine other states they can move to without passports.

But you have an excellent point.

When the population of Arizona and California outstrips the water supply, local farmers will have to give up irrigation.

Food can be imported more easily and cheaply than water adequate to grow the food , and a few thousand farmers , even rich ones such as dominate in California, must eventually lose any political fight with a few million urbanites.

Water rights in the west are first in time- first in line. A yak herding farm from the 19th century has priority and can use all the water they want. All the urbanites who moved here after the 1960s come last. You might be surprised how much political pull a few thousand farmers have. When we drank all of Mexico's water, allocated to them by international treaty, the solution was to build a desalinization plant at ginormous cost. Asking alfalfa farmers to be more conscientious with their circular sprinklers not happening. The second largest city in California, that would be San Diego, is building their own desalination plant.

Here is something on AZ water rights and the CAP:

http://cms3.tucsonaz.gov/water/water_law

and something on apportionment:

http://www.azwater.gov/AzDWR/StateWidePlanning/CRM/Overview.htm

I propose diverting it all to someplace upstream of Tucson on the Santa Cruz River, and then putting in small scale hydro.

Your first link is twenty years old. The problem of CAP water being too expensive for agriculture is still here.

CAP water is pumped uphill from the Colorado river to Tucson using gigawatt coal burning plants on the Navajo reservation in the four corner region. I can totally see a Tucson councilperson proposing pumping CAP water uphill to Mexico in order to install small scale hydro. Maybe we would get some green credits for it. This geography fact has some bearing on CAP water costs.

Well, it's been over 20 years since I lived in Tucson, and I would rather remember it the way it was then.

When Linda Ronstadt still sang.

...and if you wanted to cross Speedway, cars would stop.

I'm aware of western state water laws.

I'm also aware of how perfectly clear and unambiguous law can be subverted over time, and repealed out right , when enough people want rid of the old status quo.

The rear guard actions being fought by big ag interests California will probably succeed in delaying the inevitable for some time yet- maybe even a couple more decades if they are extremely lucky..

The ag interests are indeed worth many many billions , and they are all back to back presenting a bristling figurative wall of shields and spears in the form of 1000 dollar an a hour attorneys- whole buildings full of them - to the to the millions of people in thirsty California cities.

And as you say the law is on their side.

They can hold of the attack for a while, no doubt.

But the fecal matter is going to hit the fan in a big way some time,probably sooner than most people would guess, in the form of a water crisis( due to drought and climate disruption ) bad enough to shut down EITHER the irrigated farms OR the cities.

The farmers won't have a prayer except to collect compensation when this happens.

The president and the congress aren't going to mention even a hypothetical or theoretical evacuation of Los Angeles.

Doing so would be impossible, politically, and perhaps impossible physically, although I guess the National Guard might be able to pull it off, if enough units were called up, and the troops were willing to shoot a few hundred people every day to enforce the evacuation, and places could be found to accept millions of newly homeless , jobless, angry people.

Building desalination plants in a sudden crisis situation won't even be seriously considered, because of time constraints, never mind the financing.

The Supreme Court, contemplating the magnitude of the crisis , will figure out a way to come out on the side of the cities.

Emergency powers state and federal will be exercised, and the water will be diverted to the cities.

The lawsuits will last for decades.

When I lived in California 21 years ago, Ag consumed 88% of the state's water. Residents had strict limitations on usage, along with annoying jingles ("If it's yellow, let it mellow") everyone liked to rattle off, and draws from major rivers or the level of the Hetch Hetchy were on the TV news daily. Might as well have been "Who is John Galt?". Problem is, most of the water - canals, aqueducts, etc - flows through farming country on the way to cities on the coast. I think it would take the National Guard to enforce any change.

Joules, in your earlier work there was quite some emphasis on the use of MRC wells in the new SA development. Now you have shown mature well production declining at least 3 mb/d in the last 10 years. You also mentioned that most new wells were near the centers of the large fields. The decline then is probably the more periphral wells watering out. The question then is how soon the water reaches the MRC wells and how rapid the resulting decline will be. Too me theb future looks pretty fragile.

No more upcomming DB so I'll post it here.

NCIDC, who monitor the arctic ice and are part of the climate change research on the planet are today closed due to bad weather and flooding. A bit ironic I think.

http://nsidc.org/arcticseaicenews/

I guess this is my last TOD post unless more key posts come up so good bye all and everyone.

well if you could make do with just a little ice fix here is the current NOAA map

moderate melt on the Alaska side this year. The window Shell's Kulluk missed wasn't all that big this season.

I agree with those who've said this is the kind of article that made TOD most interesting to read... that, and the Drumbeat. Here's an example of the kind of DB article now finding their way to TEX, that it would be great to see de-constructed by the ex-DB community:

Mexico could make North America the world leader in oil production