The Retreat Of Goyder's Line

Posted by Big Gav on February 2, 2008 - 9:22pm in The Oil Drum: Australia/New Zealand

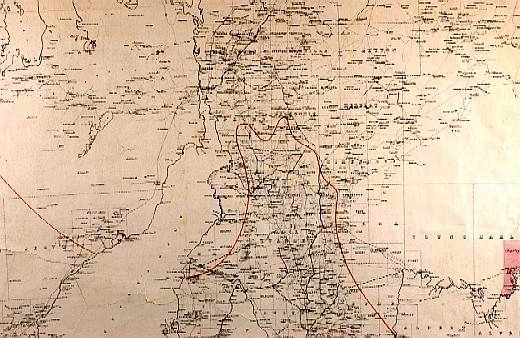

Jamie Walker at The Weekend Australian has an interesting article on the movement to the south of "Goyders Line" - the line that defines the limits of practical farming in South Australia.

See the link for an accompanying video. The ABC did a documentary on the history of Goyder's line last year as well.

An inch still means everything out here on Goyder’s Line. It can make a man or break him, realise his dreams or turn them to dust. An extra inch in the rain gauge will fill a paddock knee-high with wheat, washing away the bitter seasons and piled-up debt. That inch – 25mm – is what Kym Fromm lives for.

Yet when this third-generation farmer looks out of his home’s dirt-streaked windows, beyond the sunburnt sheep and crop stubble he’s turned them loose on, towards a horizon that shimmers in the heat, he wonders what’s going on with the line. It was the one thing people thought they could count on in an unpredictable land. It was supposed to be immovable, a fixture among the dancing whirlwinds and blown hopes of the early settlers, whose ruined homesteads dot the countryside. Fromm’s not so sure: inch by inch, year by year, the line seems to be closing in.

If this is climate change at work, he ponders, it won’t leave him all that much of a future. The past two disastrous seasons confounded all his experience of cropping in South Australia’s drought-prone Mid North. “Everything happened back-to-front,” he sighs, nursing a coffee in his leathery hands. “The rain came in summer when we didn’t need it, it was dry all winter, and what was left of the crop got burned off when the northerlies started up in spring. Crazy stuff, mate, even for this country.”

The implications go far beyond his 2000ha property near Pekina, on George Goyder’s famous “line of reliable rainfall”, three hours’ drive from Adelaide. For more than 140 years this line has marked the limit of possibility for

broadacre farming in the nation’s driest state. The colonial surveyor-general was undoubtedly a man ahead of his time. In the 1860s, he mapped where crops could be grown and where they could not. The debate he unleashed has never been more passionately argued than it is today, as drought and global warming raise new concerns about how intensively marginal agricultural lands should be worked, if at all.

The questions echo across the land, through the towns and cities, all the way to the marbled halls of federal Parliament. Are some growers simply in the wrong place, on country that can no longer sustain them? Could advances in farm practices and new crop varieties be their salvation? Or is the fight already lost (in which case, why should taxpayers throw good money after bad by subsidising them)?

Goyder’s answer, all those years ago, was to partition South Australia along what turned out to be the 10 inch (254mm) isohyet. (An isohyet is a line drawn on a map connecting points that receive equal rainfall.) It was an astonishing feat. With limited climate data he followed the rainfall contour on horseback, tracking the tell-tale break in the landscape where eucalypt forest and native grasslands gave way to sparse saltbush country. For every mile ventured beyond the line, rainfall was said to drop by an inch, until it became so low there was no point doing the arithmetic.

People set out to try to prove Goyder wrong by farming beyond the line. Few succeeded. Being on the safe side of the line – as 51-year-old Fromm is, if barely – instilled confidence that drought and disastrous seasons could be endured.

No longer. The reality of climate change has swept away the certainties of Goyder, feeding into wider concern that rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns will push vast tracts of marginal agricultural land past the point of viability. In the worst-case scenarios developed by South Australia’s Research and Development Institute and CSIRO, the line will shift south, rolling over Fromm’s dusty fields, perhaps all the way to the vineyards of the Clare Valley, about 120km distant.

Nearly everyone seems to have a theory about where the line will end up, and what that means for hardscrabble farming. Fromm is holding on – just. In 2006, he lost his entire crop. Last year was even more devastating, because for a while he had dared to believe the worst was over. Good rains in January 2007 were followed by a soaking in May, persuading him to go for broke and plant an extra paddock. Then, nothing. For a second successive year the winter rains failed.

Meticulously, he diarised the whole sorry saga. Fromm stabs a meaty finger at the entry for August 31, 2007: “Windy, 33 degrees,” he declaims, “hottest winter’s day I’ve had.” A scorching northerly began blowing on October 5 – the barley had “gone off” and the wheat was severely stressed. By the end of the month temperatures had hit 40 degrees. “Really bad,” he noted on the 27th, “Severely windy … dust everywhere.” Eventually he brought in a crop, but it was too meagre to retrieve the season. Despite near-record wheat prices he wound up $50,000 further in debt. “We had a 10 per cent chance of it going bad and, guess what, it did,” he says, draining his coffee, a long, sweaty afternoon’s work on the tractor beckoning. What he desperately needs is a return to something like normal conditions this year. If he loses another crop, he doesn’t know what will happen. Truth be told, no one really does. ...

Quite interesting as relatives used to live on Eyre Pensinsula and they would point out 'that's Goyder's Line next to that stump'. The concept of it moving was never envisaged. As farming got harder at least some locals got jobs at Roxby Downs without feeling isolated like city slickers.

For smartarses the technical term I believe is 200 millimetre isohyet. However now I think we need a 3D concept, not just rainfall contours but another dimension for rainfall variability. It may be that some annual contours (isohyets) are constant but the seasonal standard deviation is changing ie long dry spells punctuated by irregular storms. Net of evaporation the contours would change however.

The other factor governing where the line is for farming is wheat yield - the article talks about some genetically engineered varieties which do better in low rainfall environments - but this is more of a aid to retreating slowly than a fix to the problem...

On rereading the article I see they reckon more like 250mm; those Eyreheads (residents of Eyre Peninsula) told me wrong.

I think rainfall variability is a ticking time bomb. For example the 'sustainable harvest' of logs for Gunn's new pulp mill may be far less than claimed. Ditto river red gums along the Murray-Darling. We might think a tree or an annual cereal crop can take a dry spell but then they go and die on us. Alternative hardy plants may survive but they don't waste effort on high yields of oil (fatty oil, not essential oil) and plump seeds. This year could be an eye opener.

Yes - I suspect big changes are coming down the pipeline as it runs out of water.

(Well - I'm assuming southern Australia really is drying out - here on the east coast it is *really* wet)

Bill Heffernan noted in the article that agriculture is going to have to follow the water - and that means heading north (one of his occasional moments of sanity).

Maybe the great Ord River project and other similar ventures will be revived...

It's funny, Kenyans have resisted desertification for decades by a tree-planting scheme - the women planting and caring for trees in their area. And it's worked.

But I guess we don't have anything to learn from them poor darkies...

Ah yes - Wangari Matthai and her green belt - one of those Club Of Rome people (see my comments about limits last week).

I think that tactic only works if you have a certain amount of rain though - its fine for preventing desertification caused by over-grazing - perhaps not so good for altered rainfall patterns.

It's not as simple as that. Forests actually promote rainfall. Plants when hot transpire, let off moisture - that's why they turn limp in the heat, the moisture is also used for them to stand up.

The transpiration collects and becomes clouds, and this encourages other water in the atmosphere to condense ("snowball effect"), which gets you more rain.

The reverse has been seen in Australia, where removing forests dried out the land. Bear in mind that for a good part of our history we actually paid farmers to clear their land, and if you were squatting or leasing land and didn't clear it, you'd lose it.

I mean, you can't just chuck half a dozen pines out in the middle of the Simpson and expect them to do alright, you have to work with current vegetation and build out from there. And you have to choose the right trees and plants, and tend them, and so on.

Now, we are not going to turn this,

into this,

But we can perhaps turn this,

into this:

which I reckon would be an improvement.

True - thats a realistic assessment. Providing rainfall doesn't drop to near zero.

Most Australians would support tree planting...as long as they didn't have to do it personally.

I think teh Landcare movement has done a great deal for re-building the knowledge bank as well as fostering a tree planting culture. The problem still is that we have a higher level culture which dictates that a profit must be generated at some point or the exercise is worthless.

One of the main problems with agriculture, particularly if it is low value, high volume product such as wheat is the cost of getting to a market or port for export. In southern Australia all the rail lines built 100 years ago are in dire need of major maintenance but no Govt or private enterprise is willing to invest. If it goes to road transport the cost for both the producer and the public will be significant and may kill off the industry.

The mention of the Ord Scheme and the suggestions that we should follow the rains north is fine provided that Australia's population also heads north - most unlikely! The Ord is now relatively successful but only on a small scale because simply it is too far away from the major markets. To transport a product from the Ord to say Melbourne is time consuming and expensive and could only be justified for difficult to grow products or high value crops. One the main outputs of the Ord now is sugar which is exported to Indonesia.

Another issue to consider is soil fertility.

It bears repeating that Australia has generally poor soils.

There are a few exceptional areas mainly due to localised volcanic activity (eg SE SA and SW Victoria).

Pivot is a successful company for a reason.

Currently we import phosphate, apply it to land to grow crops that are removed, fed to us (directly or via cattle) and then generally all that nutrient is flushed out into the ocean.

And thats just the phosphate input.

Which brings me to another nice Age article.

Here's the beef: meat-eating days may be numbered

Now I like a good chop like anyone else... but eating 250g per day of the stuff is a bit over the top. An adult human does not need that much protein per day!

Key Quote

"...the United Nation's Food and Agriculture Organisation, which also estimates that livestock production generates nearly a fifth of the world's greenhouse gases — more than transportation"

I think what Bill Heffernan is saying is if you need steak and chips then move to where cows and spuds are easy to grow. That's maybe the Kimberley coast or the southwest tip of Tasmania. I regard water as the greater limitation since you can always make soil from a rocky base; some barren islands off the Irish coast were built up with seaweed I believe.

The cities now experiencing chronic disamenity were originally chosen as campsites by British explorers. They had no inkling millions of people would be living there 200 years later. But they do since the kids go to school, the RSL has Friday night meat raffles and their not so great job at the council is semi-secure. These people are not going to move to the Kimberley coast. Quite the reverse, environmental refugees from Tuvalu etc are going to flock to those cities.

But hasn't a flood of people from the south to the (Queensland) tropics already begun ?

(admittedly the effect has been overwhelmed by the large level of immigration more than replacing them in Sydney and Melbourne)

If "growth" (industries, jobs, property prices etc) occurs in the far north, because that is where the viable opportunities are, won't the northward migration accelerate ?

Is a council job in Darwin really that much worse than a council job on the Central Coast ?

Anyway - Bill is just talking about farmers heading north, not the population as a whole - so the RSL folk might not notice either way, so long as the steak and spuds continues to arrive at Woolies or BiLo every week.