Tech Talk - Oil Tankers in the wake of the Egyptian Crisis

Posted by Heading Out on February 6, 2011 - 9:01am

Gail Tverberg’s analysis of some of the underlying causes of the current Egyptian crisis is cogent, but one of the other consequences caught my attention today. For, as was noted in Forbes

While most equity-related assets got battered, a select group of stocks, oil shippers, were corking champagne bottles. Apart from Overseas Shipholding, Frontline Ltd. had a killer day, gaining 7.8% or $1.96 to $27.10.

An analyst for a shipping hedge fund explained that the spike is connected to fears surrounding the continued operations of the Suez Canal, amidst social unrest caused by massive riots against President Hosni Mubarak’s 30 year rule. “While Suez closure is not much of a threat, shippers are refusing to load in the Red Sea and transit the Canal,” explained the trader. “What’s probably going to happen is that they re-rout ships to the Cape [of Good Hope],” he noted.

“[Re-routing] makes voyages longer, which ties up ships and in turn diminishes supply,” said the analyst, “[this] is positive for the tanker market.”

The change involved is not just giving a tanker captain a different map and saying “get on with it.” Because of the relative size of the Suez Canal, there are different sizes of tankers involved, and so I thought it useful to talk about the different sizes of tankers, how fast and where they go, (and what the cost of that re-routing might be) in the post today.

To begin with let’s look at the traffic along the Suez Canal itself. Note that there is no immediate port of access into the Mediterranean, and thus to Europe, from Saudi Arabia or the nations of the Gulf.

The EIA, in writing about the Canal noted that

Almost 35,000 ships transited the Suez Canal in 2009, of which about 10 percent were petroleum tankers. With only 1,000 feet at its narrowest point, the Canal is unable to handle the VLCC (Very Large Crude Carriers) and ULCC (Ultra Large Crude Carriers) class crude oil tankers. The Suez Canal Authority is continuing enhancement and enlargement projects on the canal, and extended the depth to 66 ft in 2010 to allow over 60 percent of all tankers to use the Canal.

There are restrictions on the tanker size that can fit through the canal. This is mainly based on draft, or the depth of the tanker underwater, which has to be less than the 66 ft depth of the Canal, but there is also a bridge over the canal that the tankers must pass under. Those that fit into this range are designated as Suezmax tankers. In terms of the classification of tanker sizes they lie in the mid-range of those available. In a typical day about 1.8 mbd of oil passes through the Canal, which is about 5% of the global oil tanker trade.

The smallest of the tankers are those that act as coastal tankers. Typically from 300 to 670 ft long, with a draft that can go from 20 to 52.5 ft, they are used locally for the trans-shipment of refined fuel products. Ranging from 1,000 to 50,000 tons deadweight they are, most typically, the small local vessels that are often the only tankers that folk will see coming into harbor.

The design objectives for coastal tankers are demanding and sometimes contradictory, maximum volume in minimum dimensions. Operation in coastal service means frequent harbor calls, often through very restricted waterways having high currents and winds. Good manoeuvring capabilities are thus also required and, of course, high system availability to avoid incidents and accidents in case of system malfunction.

One of the more modern ones is fitted to carry either oil or liquefied gas.

But before I go on, I now need to define deadweight (DWT). It is not the weight of the empty tanker, but rather the weight of the cargo and fuel that the ship carries. In other words almost everything but the weight of the ship (which, just to be confusing, is known as the lightweight). Put them both together and you get the displacement of the vessel. So, that a tanker with a 50,000 ton DWT, with 6.3 barrels to the ton, would carry 315,000 barrels of oil. Now this is not all cargo since perhaps 5% of that total would be the fuel oil to drive the ship, which in this case would be around 15,000 bbl, giving a capacity of around 300,000 bbl. The density of the oil varies, and I used a value from one of the shipping companies, rather than the 7.3 value I have used in the past when converting shipped product.

And remember that bridge over the Canal that I mentioned? Well that brings in the other measure, known as “air draft.” This is the head room that the tanker needs, and for Suezmax this is 223 ft.

The next significant size category up are known as Aframax, and for a long while I thought that this related to some African capability. However it actually refers to the Average Freight Rate Assessment (AFRA) for the classification. A typical tanker will have DWT range from 80,000 to 120,000 tons (i.e. typically a useful cargo of around 690,000 bbl), a draft of 49 ft and a length of 820 ft. It has a typical speed of 14.7 knots. For those interested, Venezuela just bought 10 of these for $70 million each from Russia. Lloyds see a continuing oversupply of this category, to the point that (until this weekend) they projected rental costs of $10,000 a day or less, below operating costs. However there is a current hope in the industry that the rates may now rise (hence the champagne).

The next category will be the Suezmax category which has the restrictions that I mentioned above. They range up to 160,000 tons DWT.

In addition to the air draft, the vessels are limited to a maximum width of 230 ft. Such a tanker might consume 410 barrels of oil a day, and travel at about 15 knots.

Those vessels that are too large for the Suez Canal, (and for that matter many ports) divide into two categories. The smaller is the VLCC (very large crude carrier) which are those carriers above 200,000 tons DWT, and then there are the ULCC (Ultra Large Crude Carriers) carriers, which are those above 320,000 tons DWT. These are large enough that they have been used for oil storage, as well as for transport. Just over a year ago there were more than 30 such supertankers parked around the globe. At that time rates of up to $75,000/day were being charged for the use of those tankers. In September 2010 Lloyds reported that the number was around 57, holding around 70 million bbl. These are the vessels that are very hard to turn, and take a long time and distance to stop. (Don't for example try throwing out an anchor.)

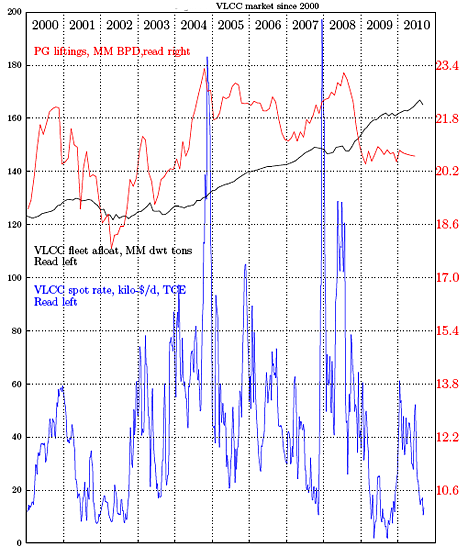

Once one gets to this size of vessel, the amount of fuel that is used in making a voyage becomes a significant factor in deciding how fast the ship will steam. Though that, in turn, is controlled by how valuable and necessary the cargo is at the time. For example in 2007 spot rates went from $30,000 a day to $300,000, but more recently have fallen steadily.

According to Devanney VLCC move at between 12.5 knots, (50% power) and 18 knots, though at increasing fuel demand (which at top speed and loaded may reach up to 800 barrels of fuel oil a day.) As he notes in one example:

Once we get to 12.5/14 kts, we note that by speeding up another half knot, we can save 1.53 days at a cost of $63,000. This is a good idea if and only if we can earn $44,000 per day (about WS53)) or better with the days saved.

The 12.5/14 knot selection refers to the difference in speeds between when running loaded, and when in ballast (i.e. empty).

If one knows the intended travel speed, then one can look up the relative distances to be travelled (remembering that the vessel has to go both ways to complete one trip). The distance from Ras Tanura in Saudi Arabia to Port Sucre in Venezuela, for example, is 10,245 nautical miles. At 12.5 knots this would take 35.6 days at sea, each way (providing that the tanker was small enough to fit through the Suez Canal).

Going from Ras Tanura to Rotterdam via the Cape of Good Hope adds an additional 74% of the miles traveled going through the Suez Canal (from 6,399 to 11,109) while adding 20 days (from 41 to 61) to the round trip.

The costs incurred from going round the Cape is related to the extra fuel consumption but also to the extra capacity required and related insurance premium increase in order to lift the same quantum of cargo in the same amount of time. Conversely, the costs incurred in going through the Suez Canal consist of canal tolls, extra insurance risk premium and the use of services such as tugs, pilotage and mooring. Canal costs have decreased by 5% over the last five months.

The break-even point at the moment is related to the cost of bunker fuel. Should this be below $370 a tonne, then it is cheaper to go around the Cape, should it be over $370 a tonne then it is cheaper to go through the Canal. (It is currently well above that price). However the break-even is a function of charter rates and other values, and so varies with time.

There is one other way of shipping oil through Egypt and that is to put some of the liquid in a Suezmax vessel to transship the canal, and send the surplus up through the Suez-Mediterranean pipeline. With the enlargement of the canal this option is less favored, and the EIA note that volume in the pipeline dropped from 2.3 mbd in 2007 to 1.1 mbd in 2009.

I have not written much on ULCC since they have proved unpopular.

As of 2010, only 12 tankers above 320,000 dwt remain. Of this, only two "true" ULCC of around 430,000 dwt are left in operation, the TI Europe and the TI Oceana, which were part of a group of four ships constructed between 2002 and 2003. The other two ships, TI Africa and TI Asia were converted into floating storage and mooring units in 2010.

.

The vessel TI Europe was built in 2002. It is 1,246 ft long, it is 223 ft wide and has a draught of 80 ft. It can carry 3.2 mb of oil. (DWT 441,893 tons.) The optimal speed of TI Europe is 16.5 knots laden and 17.5 knots in ballast.

Great post!!

Now, think of all the Energy, in Steel, Human hours and other assorted sundries, wasted on building a Ship like the TI Europe.

How many homes could be Superinsulated, with additions of Passive Solar and PV? Just a question.

Just say no, to Super Tankers, and yes, to Superinsulation!

Choose Wisely.

The Martian.

Do you have any superinsulation for sale? Cheap solar panels?

Nice article Gail, I always like the way you highlight all the various financial aspects of the world's energy infrastructure.

Heading Out, not Gail, is the author of this article.

Sorry about that--I was interrupted for an hour between reading the article and answering--still my comment stands that it is an informative piece as Heading Out is noted for and I do like Gail's way of examining different issues.

Generally I look at NRT rather than DWT and use about 7.3bbl/ton.

NRT: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tonnage

Here are a couple of listings for sale:

http://www.frontline.bm/pdf/Front_Brabant.pdf

http://www.timaraya.com/listing/626/149803_DWT_Doube_Hull_Suezmax_FOR_SA...

http://www.timaraya.com/printer.php?view=626

They have an NRT of somewhere in the 40-50K/t range so that would be 300-350k bbl for suezmax.

Rgds

WeekendPeak

Ironically another name for the Suez Canal Bridge is the Mubarak Peace Bridge. Power of suggestion, eh? Various tankers like this one which I checked out at tradewinds.no all seemed to have air draughts of ca. 50m, so this doesn't seem to be much of a consideration. It's interesting to read up on the history of the canal - it was shut down 1967-1975, leaving the so called Yellow Fleet trapped inside, to gather dust, hence the name. 30k spectators cheered the return of a German member of the fleet in 1975; an Australian ship had an effective voyage time of 8+ years.

Also on the subject of the surreal, the punchline of HO's link about VLCC's inability to throw out an anchor is that said anchor would have to be the size of a small ship itself. There's an image for you!

Anyone else seen this site that tracks large ships? I assume that tankers are included.

Notice that almost every ship tracked appears to be in port.

http://www.marinetraffic.com/ais/

DD

I was interested in AIS when I chanced across vesseltracker.com a couple of years ago, when there was all that hubub about floating storage; but it's too low-res and limited in scope to be of much use there, it seems to me. You'd spend all afternoon attempting to figure out what was offshore Galveston, then refresh and things would have changed utterly.

I wonder about the risk of sending more tankers south along the pirate-infested Somalia coast, versus through the Suez.

Good article. I wonder also if they are filling up tankers now and parking them in case the Suez gets shut down. Or are the oil companies and cartels using the unrest in Egypt to justify jacking up the prices again. The oil companies are certainly in no recession, and did very well when oil went to $149 a barrel. Why would they care about the rest of us, if higher profits are to be made? I expect this will be an outcome.

Casey - Once again I'm forced to point out that we don't have to justify our prices to anyone one. We can raise prices for any reason, or no reason, we want. The only thing that holds us back is the competition between our companies. Give us a good reason to jointly raise prices and we will. We don't care about the rest of you. Our sole design is to make a profit...not be your mommy.

Don't like the cold hard truth then change your greedy energy ways and elect politcians who'll start addressing the situation NOW!

There is not a specific high-level group of corporate oil people who set the price of oil. Like Dr. Evil's inner circle.

Think of it like this. The average American uses literally tons of oil per year or 13 times the average chinese citizen:

Here an American uses 3.4 metric tons of oil per year (or 2.8 gallons per day).

So the price of oil kind of reflects population growth and the high consumption rate once you begin to think about it some.

These so-called choke point problems could slow the flow of oil and hence the price increase is required to allow production to meet demand.

One may even expect that the current price of oil is too heavily subsidized worldwide and you should not complain at all about its price. The true price would be much greater.

Oil Traffic through the canal seems to be pretty balance (north vs south bound):

http://www.eia.doe.gov/cabs/world_oil_transit_chokepoints/Suez.html

Rgds

WeekendPeak

I recall learning that these ships basically shut down their engines while still 900 miles out at sea and coast the remaining distance. This would lead one to think that getting up to speed must require a lot of energy, I wonder how much inertial return is realized.

I grew up on Ripley's Believe It or Not, and I eventually learned that the "or Not" part was true. They would occasionally stick in the intentional fibs to keep you guessing. This sounds like one of those cases.

Pinch of salt time on that one I think.

The International Regulations For Preventing Collisions At Sea - known as ColRegs - would imply that the vessel would not be under control. Should anything happen when the engine was off, the master would be in serious trouble.

Given the amount of time it takes to fire up the main engine - which is the size of a small building - no sane captain would order it shut down whilst under way.

If you can run a ship 900 miles with no power, you could go from Seattle to San Francisco and not burn any fuel and become rich in the steamship business.

Also, what is the name and horsepower of the VLCC that can steam fully loaded at 18 knots?

Horsepower versus ship speed is a cubic relationship. If you want to double the speed, you need 8 times the horsepower and you will have to burn 8 times as much fuel.

Yes, but you will get to your destination in half the time. So for a given journey you will burn 4 times as much fuel.

Note that there is no immediate port of access into the Mediterranean, and thus to Europe, from Saudi Arabia or the nations of the Gulf.

Iraq is barely on the Persian Gulf, but the northern oil fields of Iraq are connected to Ceyhan, Turkey, a port on the Mediterranean.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kirkuk%E2%80%93Ceyhan_Oil_Pipeline

Another pipeline from Iraq to a Syrian port has been out since the US invaded Iraq in 2003. (Wonder why we bombed that one and not the one through Turkey ?)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kirkuk%E2%80%93Banias_pipeline

However, the northern oil fields of Iraq are not close to the Persian Gulf, so you are not entirely wrong.

Alan

Seems that the saboteurs know what's up. They like to bomb the pipe to Turkey all the time.

But the bigger point is that this pipe is an alt route to the Med from the Middle East, now was that the reason we invaded Iraq. I keep forgetting the REAL reason? LOL

I've sailed as an engineer on crude tankers up to 125,000 DWT.

The ships will coast through the water for a few miles, not hundreds of miles. As the Captain is arriving at a port, they'll begin slowing the engine so the ship is moving at it's "SLOW" speed with the engine just ticking over when they reach the pilot station.

The ships commonly stop at sea if they are a few hours ahead of schedule or berth availability. Diesel engines do not run well at reduced speed for long periods of time--they don't operate hot enough at reduced speeds to burn the fuel and excess lube oil cleanly. The engine can be restarted in less than a minute and be up to full sea speed in less than an hour. The extended time is for everything to warm up evenly and for the hull to regain speed to avoid excessive load on the engine.

There are some tankers that can transit the Suez Canal southbound in ballast, the empty return leg of the voyage, even though their loaded draft is too deep to transit the canal loaded northbound.

One would think it would be prudent for some of the oil refiners to stockpile loaded tankers around Europe in case the canal closes, but these things take time...getting the tanker to the loading port and getting it to the storage location. And, it is costly with the valuable oil sitting idle and the tanker charter costs adding up each day.

I was at the HDW shipbuilder in Kiel, Germany, where they have a graving dock (dry dock) built to construct 750,000 DWT tankers. They didn't build any that size, but the dock and its 900 ton gantry cranes are impressive.

Thanks for the first hand knowledge. I've been wondering about the crash stop manuever.

I'm guessing any four stroke marine engine would have to have running gear to effect a full reverse. Do the huge Wartsilla slow speed two strokes just stop the engine and reverse crank shaft rotation do the same? It appeared the shaft went straight to the prop on the pictures I saw. There are some huge thrusters on the big ships but it would seem the crash stop would require the big prop to reverse.

Thanks for the post Dave. Any idea on what percentage of ocean going oil is carried by each class of ships?