WSJ, Financial Times Raise Issue of Oil Prices Causing Recession

Posted by Gail the Actuary on March 28, 2011 - 10:39am

The idea that high oil prices cause recessions shouldn’t be any surprise to those who have been following my writings, those of Dave Murphy, or those of Jeff Rubin. Last month, though, the Wall Street Journal finally decided to mention the idea to its readers, in an article called “Rising Oil Prices Raise the Specter Of a Double Dip“. The quote they highlight as a “call out” is

When consumers spend more at the pump, they often cut back on discretionary purchases.

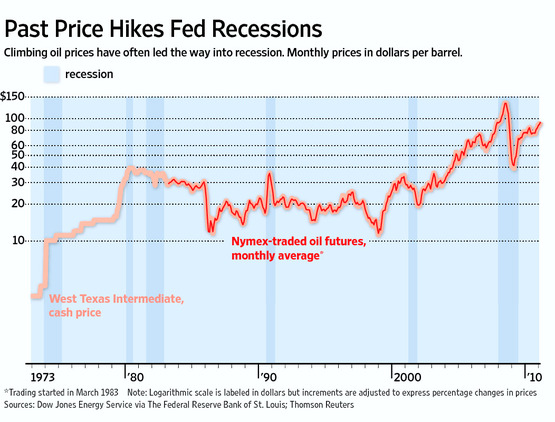

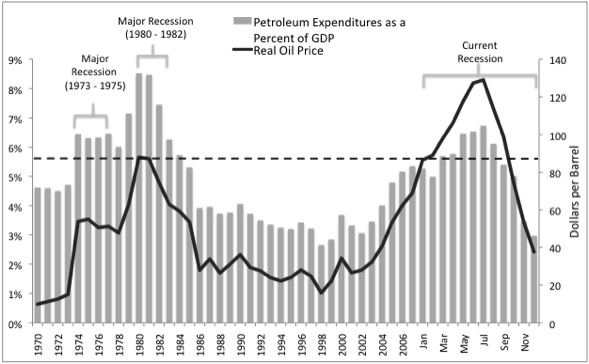

The WSJ shows this graph, linking oil price hikes to recessions:

A Financial Times blog by Gavyn Davies says something very similar:

Each of the last five major downturns in global economic activity has been immediately preceded by a major spike in oil prices. Sometimes (e.g. in the 1970s and in 1990), the surge in oil prices has been due to supply restrictions, triggered by OPEC or by war in the Middle East. Other times (e.g. in 2008), it has been due to rapid growth in the demand for oil.

But in both cases the contractionary effects of higher energy prices have eventually proven too much for the world economy to shrug off.

In this post, I explain what the WSJ and Financial Times articles are missing regarding the connection between oil and the economy. I also explain how the inability of oil prices to rise very far suggests that the downslope may be considerably steeper than most models based only on the Hubbert curve would predict.

Impacts of High Oil Prices on the Economy

The graph shown in the WSJ is very familiar. On November 5, 2008, I wrote a post called Jeff Rubin: Oil Prices Caused the Current Recession that included this graphic from this publication of CIBC World Markets.

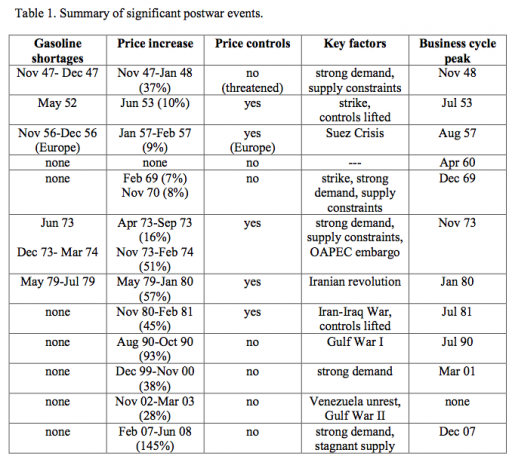

A more recent analysis by James Hamilton called “Historical Oil Shocks” published (here or here) as a National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper shows that almost an “if and only if” relationship exists between oil price shocks and U. S. recessions. According to page 26 of his paper,

All but one of the 11 postwar recessions were associated with an increase in the price of oil, the single exception being the recession of 1960. Likewise, all but one of the 12 oil price episodes listed in Table 1 were accompanied by U.S. recessions, the single exception being the 2003 oil price increase associated with the Venezuelan unrest and second Persian Gulf War.

My own research relates to reasons why changes in oil price can be expected to have a disproportionate effect on the economy. It has not entirely been published, but has been presented at conferences including the 2009 Biophysical Economics Conference and at the 2010 Advances in Energy Conference in Barcelona, Spain, and will shortly be written up in a book in Springer’s Brief’s in Energy Analysis series, under Professor Charles Hall. My analysis indicates some of the reasons for the connection between oil price spikes and recessions are as follows:

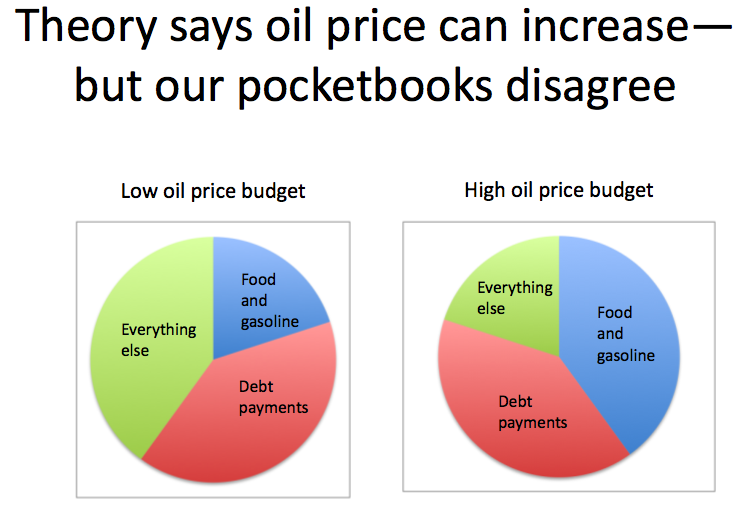

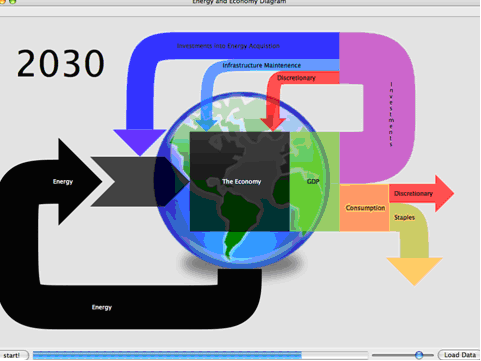

Cutbacks in Discretionary Spending. If a person (or state government, or other organization that cannot easily pass through its costs) faces an increase in oil costs, it has a tendency to cut back in discretionary spending, since many oil expenditures are for necessities, like commuting to work. This is an exaggerated graphic I put together in a post I wrote called There is plenty of oil but . . . showing that because most incomes do not rise when oil prices rise, there is a compression in discretionary spending.

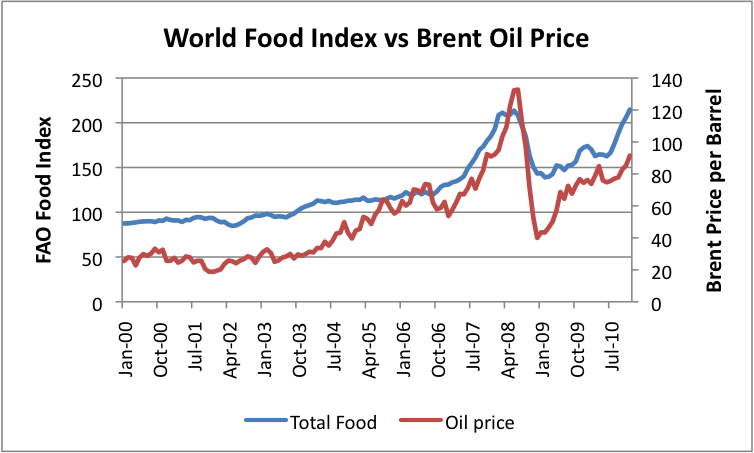

In Figure 3, I combine food and oil prices, because food prices tend to rise at the same time as oil prices. This occurs because oil is used very extensively in raising crops (operating farm machinery, herbicides and pesticides, irrigation, fertilizer) and in food transportation and packaging. A comparison of FAO’s Food Price Index and Brent oil prices (spot prices from the EIA) shows a high correlation:

Interest Rates and Inflation Rates. Higher oil food prices directly affect the inflation rate. Furthermore, if prices of other types of goods rise because of higher transportation costs, this also tends to raise inflation rates.

In the 2004 -2006 period, when oil prices rose, the Federal Reserve raised target interest rates, from 1% to over 5%, specifically mentioning rising oil prices, and their expected impact on inflation rates as a problem. To the extent that these higher interest rates affected consumer loans, the higher interest costs also acted as a reduction to income, over and above higher food costs.

The WSJ doesn’t seem to think that the Federal Reserve will again raise target interest rates this time. The WSJ reports:

In part because it is driven by something other than increased demand, the rising price of oil is unlikely to prompt the Federal Reserve to move more quickly toward raising short-term interest rates, now near zero, or otherwise moving to tighten credit. That could change if higher energy and goods costs begin to seriously feed into prices of other goods and services. But with unemployment high, a large share of U.S. manufacturing capacity still idle, and little sign that public or market expectations for inflation are moving up, Fed policymakers see the chances of inflation rising by more than their informal target of about 2% this year as remote.

Of course, it isn’t necessary for the Federal Reserve to raise target interest rates in order for interest rates on debt to rise. If investors can see that inflation is heating up, they will demand higher interest rates to compensate for the higher expected inflation rates. CNN Money shows the chart shown in Figure 5 in a February 7 article titled Bond shoppers: 10-year yields pushing near 4%.

These higher interest rates on 10-year treasuries tend to translate to higher rates for other types of loans, such as mortgages, as well. So interest rates seem already to be headed higher, perhaps in part reflecting the inflationary impact of higher oil prices over the past year.

Decline in Home Prices. Another type of discretionary purchase is the purchase of a home. A person needs to have considerable discretionary income to purchase a more expensive home. So cutbacks in discretionary income tend to reduce demand for homes, and because of this, home prices tend to drop. Figure 4 shows that oil prices started rising in 2004. The timing of the 2006 -2007 home price drop matches very well with what a person might expect, based on the 2004-2006 oil price rise and the interest rate rises that followed the run-up in oil prices.

Debt Defaults. If oil and food prices are higher, some of the more marginal buyers are likely to find it difficult to keep up their payments, and miss payments. In the 2006-2007 period, many of the more marginal home buyers were holders of subprime loans, but there are many others as well. Businesses facing cutbacks in buying because of reduced demand for discretionary goods are also likely to be affected by reduced demand, and find it difficult to pay their mortgages.

Eventually, banks figure out that loan applicants are likely to have a hard time repaying their loans, and cut back on offering credit because it doesn’t make sense to offer loans to people (and businesses) who are likely not to be able to repay them.

Balance of Payments. If oil prices rise, balance of payments are likely to get more out of balance than otherwise, with oil sellers benefitting from the higher oil prices.

What oil price level is needed for recession?

The WSJ article linked above says:

Most economists reckon that the price of oil would have to rise to at least $120 a barrel, and stay there, to threaten the recovery.

It is not clear how good an estimate we can expect from economists regarding when oil can be expected to affect the economy. The question of oil prices has only recently begun appearing on the radar screen of most economists.

One factor that may make recent estimates too low is the recent disparity between West Texas Intermediate oil prices and Brent prices. Most US analysts follow West Texas Intermediate (WTI) oil prices. These are the oil prices shown in Figure 1. WTI prices are now depressed relative to most other oil prices, as I discuss in this recent post, because of processing/shipping issues in the US Midwest. Another oil index, Brent, which many think is more representative, is $114 barrel now. So while WTI prices are “only” at around $100 barrel, other more representative oil indices are already higher.

Furthermore, other analyses show lower oil prices can lead to recessions. Charles Hall, Steven Balogh, and David Murphy did an analysis of the connection between the price of oil and when recession can be expected (Figure 6). In their view, recession is likely when oil amounts to more than 5.5% of GDP. When their analysis was done in 2008, this corresponded to a price of about $85 barrel.

If rising oil prices leads to recession, what are the implications for future oil supply?

If there were no problem with oil prices leading to recession, prices could keep on rising as much as they need to, to encourage additional production and to encourage alternatives. It is the fact that high oil prices cause recession, and the fact that recession tends to causes oil prices to drop, that prevents oil prices from continuing to rise, in a fashion that would allow oil companies, and makers of alternatives to be able to rely on the higher prices. This hampers the continued growth of oil supply.

If we think about it, extracting oil requires investment at many steps along the way: whenever exploration is done; whenever a new well is drilled, or “fracking” is done; when a decision is made to replace a broken oil and water separator; even when decisions are made to hire and train new staff members. As long as oil prices are rising enough that there is an adequate gap between the cost of production and what the oil can be sold for, there is the possibility that there will be enough funds left to reinvest.

In terms of Charlie Hall's “cheese slicer model,” if the Energy Return on Energy Invested (EROI) is high enough, there will be enough energy coming out of the red arrows of Figure 7 for both (1) New Investment in Oil Extraction and (2) Demand for New Products that Use Oil. (See Nate Hagen’s post, At $100 oil, what can the scientist say to the investor?)

On Figure 7, there are two red arrows. The one pointing to the right is the one relating to discretionary spending, and the one pointing down is the one for reinvestment. What happens is that over time, the easy-to-extract, high EROI oil, is depleted, and it takes more and more energy the extract the remaining oil. As the EROI declines, the size of the investment for new oil extraction keeps going up (the black arrow across the bottom gets larger).

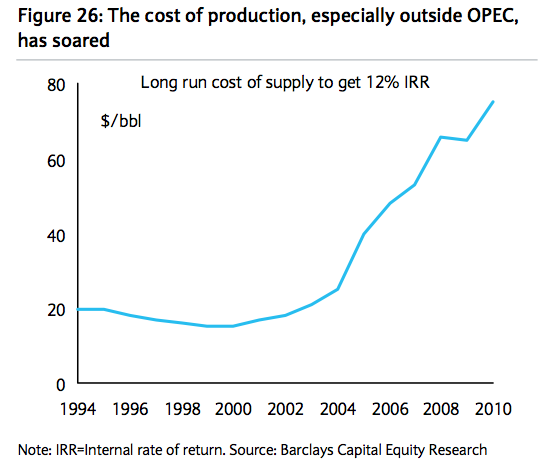

Barclay’s recently illustrated their view as to how much the cost of oil production is increasing (Figure 26 in a publication called The Return to Scarcity).

A rise in oil cost of production generally corresponds with lower EROI. I don’t know whether Barclay’s analysis is precisly correct, but it is clear that the cost of oil production has been rising, both in dollar terms, and in energy required to produce the energy we are using. What happens when increasing energy is required to produce oil is that the amount of energy coming out of the red “discretionary use” arrows becomes less and less, so the arrows become smaller.

As the red arrows denoting discretionary output become smaller (compare Figure 9 to Figure 7), the need for investment (big black arrow at the bottom) becomes larger, causing a serious conflict between what is needed for investment, and what is available for investment.

It seems as though we may already be reaching this point of conflict, especially if oil prices do not keep rising. We have been able to disguise this conflict in the need for investment funds partly through borrowing, but if credit restrictions associated with recession occur, it will become increasingly difficult to find adequate funds for investment.

The small arrow to the right for discretionary purchases (for Figure 9, compared to Figure 7) indicates that there is a constriction in demand for goods of all kinds (including those using oil), because the system of extracting oil uses so much energy itself. If the red arrow to the right were bigger, it would denote higher demand for goods and services, even goods and services made with expensive oil. But with weak demand, we get recession, rather than demand for goods produced from high-priced oil. At times, this lack of demand may manifest itself as a glut of high-priced oil on the market, because people can’t afford it. The net effect of all of this is that the lack of energy “push” from the red arrows is what brings the system to a halt. This may look like a lack of “oil demand” to economists.

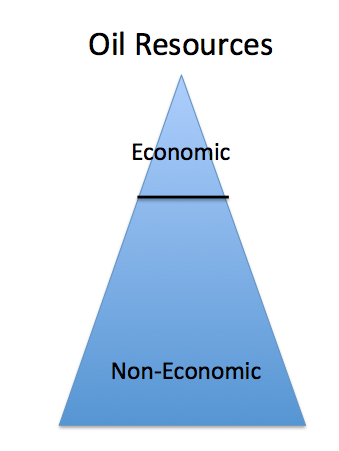

The way I visualize the situation is to think of oil resources as a triangle, with the easiest to extract at the top, and the most difficult to extract at the bottom. These resources would include both conventional and unconventional oil. These resources would also include oil that can be gotten through very advanced (and expensive) extraction techniques, as well as oil that can be extracted very simply (and cheaply).

Right now, many people assume that all of the oil resources that we can “see” will eventually be economic. But if prices cannot rise high enough, then there is a limit on which of this oil can be extracted. It is not obvious from just looking at the available resources where this might be, but the limit is there. For example, if the limit where the economy goes into recession is $120, and if a particular “high-tech” extraction method needs a price of $140 to be economic, then that approach is not going to be economic, and what looks like usable oil resources using that method is likely to prove to be a mirage. Technology improvements may cause some oil extraction to move above the line, that would otherwise be below the line, and lack of investment funds may cause some oil to move below the line.

Many people see Hubbert’s Curve as predicting a peak and slow decline, based on M. King Hubbert’s analysis of how individual reservoirs depleted. It seems to me that Hubbert’s analysis more or less says what will happen to conventional liquid oil, extracted using low tech methods. But it really doesn’t tell us much about how much oil from lower quality sources or extracted using more and more advanced techniques will prove to be economic. The cutoff really takes place when prices are not high enough relative to production costs, so that there are not enough funds for investment and to support continued demand for energy-using products by consumers.

Once we start reaching economic limits (marked by serious recession and inadequate funds for reinvestment), we are likely to be well past the point where 50% of the oil that is economic to extract has been removed. Lack of funds for reinvestment can act to cut of future development fairly quickly, it would seem to me. If prices are not very high, say $60, much of the more expensive oil production will cease.

It should be noted that this model is not really complete. There may be other types of limits in addition to the cutoff relating to what is economic. We are hearing about the possibility of the breakup of Libya and damage to oil fields. To the extent that political turmoil makes it impossible to extract oil, then even what appears to be economic in Figure 10 may prove to be impossible to extract.

See also: Developed countries share of oil

Nice piece. I doubt you would get more than 5% of economists to conclude that the 2008 recession was caused by the oil spike at that time.

Strangely enough, less than 5% of economists had any clue that the GFC was coming up, at that time.

Why do people continue to listen to manifest failures?

I have discovered at least some actuaries are quite interested in what I am saying, because recession very much affects insurance, and actuaries are not particularly tied to what economists are saying. I was at a conference this week, and talked about the connection between oil price spices and recession, as well as the fact that exponential growth cannot go on indefinitely in a finite world. My talk was well-received.

Given that "finite" is not a recognised economic concept, I'm not surprised.

I think the fact that your talk was well-received among actuaries is very significant. Actuaries have a huge influence in the insurance industry. Would you say that when actuaries speak, insurance executives listen? Executives may not always make their decision based only on what actuaries say, but I imagine they pay close attention. That may determine what industries can get insurance and at what price. If the price of insurance for oil companies goes up, would that not be another factor in what oil becomes feasible to exploit?

I think the reason the talk resonated well in the insurance industry is the fact that they are aware that recessions have always affected insurance companies by a huge amount. One of my employers "went under" subsequent to the 1973-1974 oil spike; another of my employers almost did--had to be bailed out, by a buyer who bought the company for $2 a share. This is one reason I have always worried about a connection between oil limits and the health of financial institutions.

There are some companies that are affected favorably though. If people drive fewer miles, private passenger auto rates may prove to be too high in a recession.

Actuaries are not as "hung up" by the pronouncements of economists as a lot of business people /economists, because they generally have not had a lot of economics courses. Typically, they have majors (or masters degrees or PhDs) in math or a hard science. Some of them have had quite a bit of exposure to what happens in practice with the financial system, though. I also think of actuaries as being practical, rather than hugely theory driven. There aren't a whole lot of actuaries from Ivy League schools; most seem to come through university systems or local private colleges. The Casualty Actuarial Society exams are given outside of the university system, so most people work and study the actuarial material on their own.

I am not sure that this particular talk will reach terribly far, because it takes time for new ideas to work their way through the system, and the initial impact was only the people in the breakout session at the Ratemaking and Project Management Seminar who heard my talk. People who are aware of what I am doing are writing about it though. Two different people plan to write up the work I am doing, one in a publication for insurance executives, the other in a publication for actuaries. There has also been discussion about putting this subject as a major panel at the Annual Meeting later this year.

Beware of this article...

As an economist and mathematician with years of experience in forecasting models,

I would urge some circumspection here.

(1) The record of forecasting models in economics is generally poor. The oil analysis

may have some nuggets of gold in it BUT in general one ought to be cautious on

interpretations.

(2) More specifically, I would argue this...

Recessions often occur after a period of growth. A consequence of growth periods

is resource exhaustion, and higher prices of eg oil, food etc.

Recessions can be caused by different factors.

When a recession occurs finally after eg a boom, it is likely that one will

notice that oil rose prior to the recession.

This does NOT necessarily imply oil was the cause in ALL cases.

Oil may have been the rpimary cause in some cases;

a secondary cause sometimes; or frankly not really a factor, more of a coincidence

of timing.

Economics, being the study of human productive and financial interactions is complex.

I abhor any explanation which takes ONE factor and says..there that's it.

Life in general is MULTI-FACTORIAL in its driving motives.

I am not convinced that the issue is oil by itself. I think energy in general is an issue, and oil prices quickly spill to food prices.

Electricity prices have not spiked in the same way as oil, and in fact, are now down a bit because of low natural gas prices. If electricity prices were to spike, or if electricity were to become less available, as it is now in northern Japan, I expect that these would also have a huge impact on economies.

Yet, I'll bet that you wouldn't have a problem blaming it on an increase in interest rates if that had happened. That would be a single factor that can bring on a recession.

Oil touches almost every step of production in our modern world. An increase in the price raises the cost of raw materials, transportation, manufacturing, it raises the price that the workers have to pay to get to the factories to make everything. An increase in oil prices is a de facto value added tax of enormous magnitude that hits suddenly, and without warning. When almost all costs go up, everything being equal, profits must come down. When profits go down quickly at every stage of production, how can you possibly avoid a recession?

In fact, you could argue that it is worse than a value-added-tax, because the money is not staying in this country, an enormous amount is transferred over seas in the form of a trade deficit. At least in earlier recessions, the increased profits from higher oil prices that oil companies received, stayed mainly in the U.S. and helped even things out.

http://cr4re.com/charts/charts.html?Trade#category=Trade&chart=TradeDefi...

Now the money goes to the unstable ends of the earth and Canada. There is also no shadow banking system left to recycle that money back into mortgages and CDOs.

There are all kinds of indirect effects too. If people have less income to spend, they can't afford to buy more expensive homes, and the demand for homes goes down, as does the price of homes.

One would expect the stock market to go down, but with Quantitative easing, the stock market tends to stay up, and interest rates tend to stay artificially low. It is not clear how well the government will be able to QE, without the bad impacts reappearing. The Economist had an article recently, called Stopping quantitative easing may be harder than starting it.

Something wrong with this link Gail?

It should be fixed now.

Some people point to Canada as evidence that the recession was caused by other factors. One argument goes that Canada had no real recession because they kept tight regulatory control over their home loans. But then again, they have a much larger oil reserves than USA especially with respect to their population base. Which factor tipped the scale?

I'm not quite sure of the answer, but I suspect it has to do with the fact that Canada is an oil exporter, and the US is an oil importer.

When oil prices spiked, OPEC countries did well, and so did Canada. Additional funds relating to the higher price of oil flowed back to Canadian stockholders and to employees. Employment in the oil industry rose. I had thought that the fact that OPEC countries limited oil prices to consumers made a difference (and it no doubt did), but it may be that the higher oil prices, and higher employment (leading to higher demand for homes) also played an important role in helping these countries avoid recession.

The US is an oil importer, and in fact has been an oil importer for the entire time period since World War II. So Hamilton's study is really of the impact of price spikes on a large oil importer. In the US and quite a few other OECD countries, high oil price seems to trigger lower consumption. In Canada, high oil price did not lower consumption until 2010. See Energy Export Data Browser. Lower oil consumption seems to be correlated with recession.

Edit

When I look up economic growth for Alberta on Google, I find that in October 2006, an article says,

A Januuary 2008 report says, Alberta Economic Growth the envy of other provinces.

The Alberta Quick Economic Facts says

So the oil riches have spilled through to a very low tax environment otherwise.

I wonder what kind of economic growth the rest of Canada had. I expect it would be fairly much reduced, if oil exporting areas were excluded.

Generalizations can be fairly dangerous.

No doubt the energy resources including the oil in Alberta helped make the recession less severe in Canada, but Alberta is less than 15% of Canada by population.

Other factors that clearly had a role in limiting the recession were a budgetary surplus going into the recession and relatively sound banking practices. Specifically, the sub prime mortgage market didn't really exist in Canada and an number of other shady practices such as paying a fee not to document income, and securitization of mortgages were not allowed.

The world is not as simple as I would like it to be.

I wonder what kind of economic growth the rest of Canada had. I expect it would be fairly much reduced, if oil exporting areas were excluded.

The rest of Canada did not fare so well. Canada's auto industry (centred in Ontario) had to be bailed out same as the US, some major retail companies went broke, as did many other businesses. The property market did not collapse aka the US, but did get the wind knocked out of it's sails. Many projects have been halted, many property developers went broke, lots of construction industry workers laid off/reduced hours etc. The maritimes have been an economic basket case for years, so this didn't help that cause. Quebec is, well, Quebec - they used this to leverage even more money form the fed gov - that has been a "long bailout" if ever there was one. The prairies have done OK, because they produce lots of food and some oil. And here in BC, where no one will really admit that the economy is based on property development and retirees (from the rest of Canada), well the property market died and retirees stopped coming here and/or spending, with predictable results.

My take on Alberta it is that the oil industry, and governments, who receive oil royalties and taxes from oil related companies, did benefit from higher oil prices. However, lower natural gas prices were not so great - they took quite a chink out of Alberta's revenues, though I'm not sure if it was made up for by oil. Alberta gov was debt free in 2007, but has had to go into deficit to do its own "stimulus spending" , so Alberta did not escape unscathed. Even the oil industry had its casualties - many oilsands expansion projects were shelved - some have resumed, but many, particularly heavy oil "upgraders" have not. Rocky Mtn guy is the exert here though - he can give a much better picture on Alberta (and Canada in general, actually).

Also, keep in mind that 87% of Canada's exports go across the border, so no matter what Canada does, if the US is in recession, Canada will feel the pinch. The US has more cross border trade with Canada at the Windsor-Detroit bridge than it does with Japan, so you start to see how big of a deal it is for Canada. One politician described it as being in the same room as a wounded elephant - you have to make sure it doesn't fall on top of you! The steadily rising Cdn dollar (or depreciating US dollar) has hurt the exporting industries that are still operating.

Some protectionist US policies didn't help either, like the requirement to use only US made steel on gov funded reconstruction projects - caused some trouble for long time suppliers, and ensured US gov projects got less for their steel dollar!

Overall, the economy was not nearly as over-extended as the US, so there was less pain to be had, but no matter how good any business is, if your biggest customer is in trouble, you share some of the pain.

Beating the US for the hockey gold medal at the Olympics provided a brief distraction from the depressing realities...

All of what you say is true and very well put, but still the complaints got fairly thick in Canada when the recession threatened to head into its 3rd quarter and unemployment inched over 8.5%. Note that this performance is far less harsh than than what happened in most other parts of the US. The Canadian economy tends to suffer more frequent, longer and deeper recessions than the US economy for all of the reasons that you detail. The variance from the normal pattern of the Canadian economic is surprising and contrary to recent history.

It is undeniable that high oil prices were a trigger for the recession. (Gas prices peaked at about $6.00 per gallon.) It appears to me that the difference in performance comes largely from the institutional framework that dampened (rather than amplified) the feedback loops once the recession hit. Specifically, better banking (and especially mortgage lending) practices prevented the housing market meltdown and protected the financial system.

Construction slowed down a bit, unemployment went up a bit, and government deficits reappeared as they put in stimulus programs to counter the recession. And then, surprisingly sluggish growth started up.

It was very clearly not the oil industry in Alberta that ended the recession. The conventional oil production seems to be stable to declining. The tar sands were struggling with a cost squeeze before the recession hit. Steel was in short supply. Labor was in short supply. Fuel prices to run everything from heavy equipment to heaters to liquify the tar for extraction were making operations very marginal. When the recession hit, oil demand and prices dropped. New projects were put on hold. (All of the foregoing seems to fit pretty well with Gail's analysis.) Alberta didn't really get going again until after oil prices started to go up and after sluggish growth had returned elsewhere in Canada.

About 1000 days before you joined us, Gail gave a forecast for '08. Maybe we should beware of you.

http://www.theoildrum.com/node/3382

The Barclay's piece tells an interesting story and I believe it is the ultimate driver of prices at peak oil. Last year, I predicted much higher oil prices due to the distinction between "cost push" (Barclays illustrates) and "demand pull inflation". The interesting, worrisome and key question will be how long this 45 plus degree trendline will continue and how high it will go.

The cost-push story is really a "declining EROI" story. We are rapidly reaching the point where EROI is too low to support all of society's needs. This is indeed worrisome.

Very good report Gail. I agree with your views that finance and politics will be the big game changers as oil supply diminishes. It always has been !!

Gail

It is not just the WSJ or FT that are taking notice. I see increasing commentary in the British press, specifically the Daily Telegraph's Ambrose Evans Pritchard's recent articles on world food and the margin of spare world oil capacity, that begin to connect the different pieces of the scene.

I am interested in the geopolitics of food production. With regard to food and food pricing the world has not stood still in the last two decades. In particular, increasing urbanization and industrialization, and westernized dietary changes, have driven up the need for primary food commodities to be internationally traded. Competition for these internationally traded food commodities appears to have been on a long term upward trend.

My guest post you posted on ToD in 2008 http://www.theoildrum.com/node/5181 has an FAO chart that illustrates the trend in international trading of cereals, increasing from a previously low base. The chart is only to 2003, but the trend continues.

http://www.fao.org/es/esc/en/15/70/81/highlight_79.html

The internationally traded cereals depend on areas that in turn depend on high inputs of fossil fuel, including oil. (The trends in fertilizer pricing are more complex.)

There seems to be a tightening of the coupling between fuel costs and the cost of food supplies for urban populations (affordability) but I note that some important areas are not in recession. 'Emerging' economies like the BRIC countries, illustrate the point. I read also that even in the USA there are disparities between 'growing' and recessionary areas; the big agricultural producing States have been described as more like an emerging economy; seeing growing prosperity with fewer municipal and State financing problems compared with the rest of the USA.

Is 'recession' more of an affect of competition, where there are winners as well as losers? The balance between growing and shrinking economies has some interesting tipping points.

best

phil

Fill up, set the cruise control to 55mph, and watch 1000 miles of open freeway roll by. (If you can find 1000 miles of open freeway without major hills)

"When consumers spend more at the pump, they often cut back on discretionary purchases."

Duh of the day.

"If you can find 1000 miles of open freeway without major hills)"

Cheyenne, WY to Columbus OH. I've done Billings,MT to Madison WI more than once.

My discretionary spending is restaurants in cities. I also tend to drive up and down interstate 35 for about 2-4 hours at a time, and I spend quite a bit more on food in a week than I do on fuel.. I also get about 60 miles per petroleum gallon when running a prius on E-40, and the corn that made the ethanol that has provided 30-50% of my fuel energy for the last 90,000 miles is also providing DDG's to raise the roast beef I had in a sandwich yesterday. The petroleum I burned is just gone, one use only.

The biggest impact on my mileage is not whether I put 50/50 gas/ethanol in, vs straight gas... It's what direction the wind is blowing. That 80mpg vehicle will drop to 45mpg with a 25-40mph wind coming at the car from 20 degrees off the direction of travel. The best you could do is maybe 100mpg if you have a low-turbulence tailwind coming exactly from behind the vehicle.

What you see in that 1000 miles of open freeway is a lot of farmland, and in Iowa/Minnesota, you see a lot of wind turbines installed as well as on the road en-route to installation. You can also find a lot these blender pumps outside the cities too..

Hummers are so last century. What you need in these more environmentally responsible times is the Cadillac CTS-V Sportwagon. A 6.2L/556-hp/551-lb-ft supercharged OHV 16-valve V-8 propels it 0 to 60 mph in 4.2 seconds.

At EPA city/hwy fuel economy of 14/19 mpg, this appears to be Cadillac's answer to the Volt.

http://www.motortrend.com/roadtests/wagons/1012_2011_cadillac_ctsv_wagon...

Perhaps it's more correct to refer to 'fuel burn' than 'fuel economy' on this vehicle. :)

Recession in a country is closely tied to how much oil a country is able to consume. OECD countries have been declining in their share of the worlds' oil consumption, even as world oil production has been flat. This explains how OECD countries were in recession, even as BRIC countries continued to expand.

(I believe you typo'd: OECD, not OPEC)

Comment: Fixed it. Thanks!

The graph says OECD. Your comment was about OECD, right? Then what about OPEC? Wouldn't their share of consumption be expected to be flat or rising?

OPEC is part of the remainder. It is in the piece with increasing consumption. (Sorry about the original typo--it is now fixed.)

Hi Phil,

We have similar interests. Wanted to get more of your take on the situation.

It is amazing to watch the quantity of land being brought into production in tropical countries. Much is geared towards the cereal export market. One thing that concerns me is the input costs of this. How costly is it to fertilize those highly oxidized, wet tropical soils?

I see it similarly to this issue of how declining EROI for oil impacts reinvestment funds for further extraction. Does the world reach a point where food prices need to be very high in order to justify the cost of fertilizer applications? And since food is a staple like energy, does this cut so much into discretionary spending to cause recession and dampen the ability to invest in food production?

While this all worries me, I do see the world essentially wasting a huge amount of cereals each year so theoretically we have a large buffer if distribution inefficiencies could be improved.

Refrigeration and good transportation have helped distribution inefficiencies. It is possible we could see an increase in distribution inefficiencies, before there is a complete return to relocalization at some point in the future.

Investment in storage and transportation is likely leading to less spoilage of grains. However, my comment on inefficiencies of distribution was about the proportion of cereals going to biofuels and animal feed, and the ability to afford food during economic duress.

Most biofuels are complete waste (i.e., corn ethanol), while grains to meat is a caloric EROI of ca. 1:8. Therefore, even with a huge decrease in the amount of cereals produced there'd theoretically be plenty of food. Just that in such a situation (meaning a world in which cereal production crashes because of declining investment in production) I worry about how many people would be unable to pay for food.

Jason

I have only just come back to this discussion.

Thanks for your thoughts. I agree with your point about 'inefficiencies', where calories and primary protein go for animal feed, or heaven help us, the calories go for biofuels.

Despite the modern trends and their profitability, the large majority of the world though is still not fed by the internationally traded cereals and legumes, which are still a minor part of total world yields of these crops. However, these globally traded bulk commodities have increased as a proportion of total world yields and are critical for price setting. There always have been large populations subject to 'food insecurity' as long as I can remember, but a very few years ago I thought that 'world food security' would not be a general issue for another 20 years. However, the speed of developments seems to match those of the 'energy issues'. Modern trends might continue, while at the same time, more and more people are hard put to it to afford food? The situation in North Africa, Middle East, perhaps illustrates the coming dilemma for much of the world? (The first part of my 2008 TOD guest post, linked already above, refers to a 1999 paper by Dyson that addresses potential regional vulnerabilities. Some but not all of his analysis is proving prescient.)

I wish I knew more about tropical soils. The British Empire did a lot of R&D in tropical agriculture, plantation crops and forestry in particular, but in general found introduction of temperate modern agricultural methods inappropriate in the tropics. The 'green revolution', when it came with new varieties that could use high NPK fertilizer input, transformed yields in the vast intensive traditional agricultural systems of Asia as well as in our industrialized agriculture, for a while. The question in my mind this last 15 years has been whether rapid industrialization elsewhere and the need to feed the growing urban populations in places like China and India will adversely impact their vast and populous rural economies, which must compete against the world market. Governments in those countries have no option but to ride the unstable situation. The situation looks increasingly unstable to me, and the cropping of new land in the tropics seems high risk and likely to be part of the problem, not the answer. But like biofuels, these ventures could be highly profitable in the short term.

best

phil

Nice work Gail. So what is the current global cost of extraction for conventional oil per barrel? Anyone know?

Gail, what about investment in renewable energy sources then? Won't there be an impact there too, and not for the good?

Investment funds are limited, and we now have an inflated view of how much investment funds are available, because of the borrowing (particularly government borrowing) that is being done. The government borrowing is being used for stimulus funds and to support investment in renewables--also the subsidies are having the same effect.

The high price of renewables on a delivered basis indicates that they are very low EROI energy sources on a "delivered" basis--there is a huge difference between the "wellhead" basis and the "delivered" basis which standard EROI calculations do not measure. The fact that we are supporting investment in high priced renewables takes investment dollars away from higher EROI investments.

The system is not sustainable, but "picking winners," when the winners represent expensive ways of saving a little natural gas, doesn't help at all.

If there was something that truly worked and was cheap (thorium for nuclear??), it might be helpful.

For all practical proposes there is only one renewable liquid fuel at the moment that amounts to anything: ethanol.

This paragraph makes no sense in regards to ethanol. We are not supporting ethanol more than oil. If all the tax subsidies, expenditure for oil wars and defense of shipping lanes are taken into account the cost of oil is much higher than ethanol.

The economic cost of imported oil is higher still since resources are sent of of the country to pay for it. This is the main reason the economy goes into recession with higher oil prices.

If the oil were coming from the American economy it would not matter so much since the higer expenditure would stay within the economy. This is the big benefit of ethanol that ethanol critics refuse to talk of even think about.

They remain fixated on meaningless comparisons of different things using EROEI. Even oil that is exactly the same is different depending whether domestically produced or imported. EROEI doesn't even recognize this problem. EROEI is nonsense.

It may have some utility comparing two ajacent oil wells, but $RO$I wouild do the same thing without all the hocus pocus. All oil is not the the same even if has identical characteristics. It matters that oil is imported or not.

Imported oil is especially toxic as oil prices rise. On the other hand domestic produced ethanol which keeps resources within the economy does not have this problem. If its prices rises the revenue stays at home without the draining effect that is participating recession after recession as Gail correctly points out.

It is hard to understand why energy analysts can not see the importance of domestically produced liquid fuel over imported.

It is blind spot they refuse to acknowledge.

I agree that imports are definitely worse than home-produced energy, but even locally produced low EROI energy is a problem.

You missed what X said that he does not believe in EROI.

I suggest that we give X enough fossil fuel to grow his corn for one season. At the end of that season he can sell off his corn for food or to a distillery. The catch is that every subsequent year he can only refuel using the ethanol that came from the distillery that he sold his corn to and the distilled fuel they produced from his bushels. That is he has to buy it back. He can't use any gasoline or diesel for anything related to farming. We can also extend that to natural gas for his fertilizer.

This is called a bootstrap experiment. See how far he gets.

The same can be said for wind farms and solar in terms of embedded energy, but we all know this is a factor. But we don't appear to go to the lengths that X does to create some fantasy land for ethanol.

Now I understand why he calls himself X. If X is the amount of corn he sells as food and 1-X is the amount that he sells to a distillery, I wouldn't doubt that X may turn out to be a big fat ZERO.

If I have some of this problem statement wrong, let's clean it up a bit. It might help people understand EROI.

"If the oil were coming from the American economy it would not matter so much since the higer expenditure would stay within the economy."

X is right here, but only to a small extent. In his hypothetical situation oil profits would enrich domestic oil producers and their shareholders, but high oil prices would still create a massive reduction of discretionary income for the middle and working class. Thus the U.S. would be in a similar situation to where we are now--the economy has hit a ceiling because the middle class' pocketbook is over extended and consumer spending can't grow. Oil profits are great for the rich, not so much for the rest of society unless there is substantial redistribution of wealth. In the case of ethanol we can say that domestic production creates wealth for midwestern farmers and Con Agra, but less so for the average American (without the redistribution of, in this case, federal subsidies).

The game-changer here, in this hypothetical situation, would be if the federal government nationalized our oil or ethanol resources and sent out royalty checks to every family, something like Alaska has done. That would truly keep oil profits within the domestic economy.

We get statements of this general sort all the time, and each and every time they still carry the strong whiff of the Broken Window Fallacy. Even if cycling the money (i.e. markers) more directly might be slightly better, in the end, fruitless makework is still just fruitless makework. Some variation of Fischer–Tropsch would surely be a much less Rube Goldberg way to convert coal and natural gas into liquid fuel.

Actually, FT itself is not unlike like a Rube Goldberg process - very complex and must be very well managed . A good write up about a real FT facility is by Robert Rapier when he went to Shell's Bintulu GTL plant in Malaysia

Doing coal/gas to methanol is much simpler...

Either way though, you are facing much higher expenditure with these X-to-liquids technologies.

Gail,

I always love your posts! I have another somewhat depressing thought. What about the established interests in the economy? Why would they have an interest in seeing alternatives (any alternatives) from upsetting their existing profitability? I would expect that the normal rules of competition would "force them" to defend the existing technologies and make it very hard for new entrants. For example, one could make a good case that battery technology has been neglected (suppressed?) in the effort to maintain the current ICE car market. This could extend all the way to influencing the political process through donations to "friendly" politicians, i.e. those that would favor the existing large market entities over potential "threats". I would think that this would increase the risk of the existing technologies being stretched past their useful life and increase the chance of a "discontinuity".

I use this paragraph as a preamble. I believe that there are a FEW possible alternative technologies that offer some technological hope of ameliorating the decline. However, I am very worried that the existing economic order would make the widespread acceptance of such technologies much more difficult than it would other wise be. I would love to see Thorium fission reactors become a reality in the world. However, combined heat and power would seem to be a more likely short term partial solution to some of the problems posed by the Peak Oil challenge. My favorite long term "solution" (not a real solution but a hope), is Chemically Assisted Nuclear Reactions-CAGR (sometimes called "Cold Fusion"):

www.lenr-canr.org

There has been a huge volume of peer reviewed work accomplished since Pons + Fleishman to show that this is a real physical phenomenon (e.g. more than 5000 peer reviewed publications). However, it is a long way from a practical energy source that would enable cheap electricity as a substitute for coal and natural gas. It is ever farther from anything that could substitute for liquid fuels in vehicle and aircraft. I have some hope nevertheless. Perhaps it is a fool's hope, but as long as we pursue the best energy policies that we can under the assumption that fossil fuels are going to decline pretty rapidly, perhaps it is worth some small amount of research investment (e.g. 1-5% of energy research), in a possible breakthrough technology, perhaps it is worthwhile.

Hope springs eternal in the Human psyche!

I am not sure that work has been neglected (suppressed) on batteries. We had electric cars 100 year ago, that were only marginally worse than the ones today. See last year's guest post The status quo of electric cars: better batteries, same range.

Furthermore, if we lose nuclear power because of (valid) concerns regarding safety, the whole idea of recharging cars off the grid may be moot anyhow. Nuclear is a big source of power (20% in the US, including 30%-35% on the East Coast). If the licenses for these plants are not renewed when they come up in the next few years, it will be hard to maintain the current level of electric power service, much less add more for electric cars. I have written about this on Our Finite World, here and here.

It would have been good if our original nuclear research had been along the thorium route. Maybe we could have gotten that to work.

At this point, it is getting late to start ramping up new technology.

Gail, Thorium may be a possibility. Some intermediate technology may be appropriate in the near term. We must address depletion of low cost fossil fuels, over-population, and climate changed. A good path is to trust science and technology. Embrace modern Ag and nuclear power. Provide affordable nuclear power to the third world so that they can industrialize and grow their economies. The solution to overpopulation is wealth and urbanization. Nations with GDPs above $7500/capita have negative birthrates. Urban women choose to have small families.

Energy is equal to wealth. Nuclear power is an inexhaustible energy source and its energy density is 50 million times greater than chemical energy on a volume basis. New generation reactor designs are needed to produce electricity cheaper than dirty coal plants.

TerraPower is a company founded by Bill Gates for the express purpose of building a high temperature Traveling Wave Reactor (TWR) with potential to replace liquid fossil fuels and coal. The aim is to combat global warming. The TWR is designed to use the spent fuel from our current LWRs and it will be loaded with enough fuel to operate for 60 years without refueling.

Prof. Per Peterson at UC Berkeley has designed a low cost Pebble Bed Advanced High Temperature Reactor. The power output of a full-sized 4 m tall (2 m wide) reactor core unit would be 400+ MWe, which is surprising large for such a small size core. The driving aim is to get these units commercialized in the near term, and to bring down costs, thereby paving the way for later widespread commercial deployment of full Generation IV designs like the LFTR and IFR, which not only achieve high burn up, but also completely close the fuel cycle.”

Nuclear fission can provide the energy to make affordable liquid fuel from water and carbon dioxide. Iceland is building a facility which will open in 2014 that will produce dimethyl ether from carbon dioxide and hydrogen. Dimethyl ether is a clean fuel for diesel engines. They expect that the new dimethyl ether plant will reduce their imported petroleum of by one third. High temperature nuclear reactors can split hydrogen form water at high efficiency. The thermo-chemical splitting of water at high temperature looks like a winner. One such system uses sulfuric acid and iodine as catalysts. I have read of 60% efficiency for hydrogen production at temperatures in the 900 to 1000 degree C range. Synfuels can be produced by chemically reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide with the efficiently produced hydrogen. Wealth remains in our own economy when we use domestically syn-fuels. The hydrogen split from water can also be used to make nitrogen fertilizer. Five percent of our natural gas is now used as a source of hydrogen.

For our environment's sake and our economy's sake we need to embrace modern Ag (including genetically engineered organisms) and nuclear energy. To do otherwise will place our grandchildren in a world of mass starvation.

I'd prefer to see relocalisation, reduced consumption and a simpler way of life as a prescription for change. The quest for technological "solutions" to the mess we find ourselves in seems to me like (to paraphrase Einstein) using the same thinking to fix a problem as was used to cause it.

Or, to put it another way, working with nature instead of constantly challenging it.

I agree in principle with all you say;however, in the short to mid term, our only slim hope for preventing a dieoff on the grand scale is to embrace science ant technology.

There is simply no way we will ever reduce the population fast enough to swith over to a renewables based economy without suffering a major dieoff-with the associated wars that will accompany the resource crunch thrown in by the devil(figuratively speaking) for additional good measure.

The things that will kill us over the long run are the only things that can get us, or at least might get us, thru the short to medium term still in the land of the living..

It is interesting to revisit EROI ideas in light of the cost of oil these days. The premise that the decline could be rapid as opposed to a smooth descent makes sense. As the cost increases, the relative standing of one currency against another will also become problematic as money buys less and less in real terms. More change than the US dollar as reserve currency, will large purchases of oil one day be bartered for other goods.....say... we will provide 15 f-15s for .....? (We don't want your stinkin money, man) Seriously, if the profit is hard to predict, then why would any sane business invest billions in dollars and effort to be paid in funny money of decreasing value?

People lose millions playing the airline game; the lure, cachet, and flying is irresistible for those infected. I find it hard to believe the same willingness to play a losing hand exists in resource exploration and oil production? (Panning for gold excepted, of course.)

The plateau dropping away as predicted by Ron and others starting 2012...with an upward view of 2020. The staircase model seems likely as the struggle for BAU renews over and over, until one day we wake up and walk towards a simpler life. This could be a fine scenario for those prepared and living in a benign place of hope, but God help the rest of us.

Thanks for a great article.

Paul

The basic decline curve when available resources have been extracted in the animal world is overshoot and collapse.

The Limits to Growth book from 1972 tries to look at the interactive impacts, and comes up with a decline scenario, starting about now (varying, depending on the scenario chosen). The book very explicitly says its model is not set up to determine what happens after the decline scenario sets in, because things will be so different then.

It seems to me that during the decline phase, Liebig's Law of the minimum will come into play, quite a bit. There may be some additional oil available, as societies drop to lower levels, and can function on lower EROIs. But this is likely to be offset by countries overthrowing their rulers, as conditions become intolerable. The new governments are likely to function less well than the old ones--some states may break up into component parts. This was a post on my view of Libya's situation, which did not run on TOD. I have a hard time believing that a new government will be formed which will keep up oil production as well as the old one.

It is hard for us to foresee precisely what will happen. But we can already see what happens when a little part for new cars is not available. If some oil production is taken offline because of revolution, or if the EU dissolves, or if major countries dissolve, there could be much bigger impacts.

As I recall, Limits to Growth and its sequel Beyond the Limits both targeted about 2012 as the year when worldwide industrial economic production would peak for BAU. One of the scenarios which gave more credit for improving technology pushed things out another 20 years or so.

Thanks for the article. One of the most interesting points is Figure 8, the cost of production. One would like to read more on that.

Unfortunately, this is one thing that it is hard to get good numbers on.

Sometimes, even when numbers seem to be available, for example on the oil-rich plays in the US, it is hard to interpret them. The calculations are set up as if the huge initial investment will in fact make extraction over a very long time period (40 years?) possible. If this assumption is wrong, the calculations will make it look like less investment is needed than is really the case.

Thanks. It makes sense that the numbers are hard to come by ... which means informed estimates based on projected total output for a given area are the best we can do. And of course weeding through the spin of the numbers-producers is a must.

The value of oil is much greater than its retail price.

Over at Automatic Earth blog they partially dismiss oil prices as a cause of recession. If you just take cash value of fuel this seems reasonable, but less oil means less work done. Less work done feeds back through consumer confidence and all the other complexities of the economy.

If you just count the cost of the fuel and don't look at the losses from people not travelling, not working, not visiting the malls, not going on holidays, not ploughing the land the cut in oil use multiplies its effects. Less oil burnt means less professional drivers and less jobs.

Max

There are a lot of different connections with oil. Some posts I have written on Our Finite World that are not on TOD include

How is an oil shortage like a missing cup of flour? and

The Oil Employment Link, Part 1

The many connections between oil and the economy is really the theme of my book, which is tentatively being called, "Beyond Hubbert: How Limited Oil Supplies Cause Economic Crises".

In the best scenario I can think of, we will all stop driving, and we will walk around our neighborhoods or small towns, write poetry, have plenty of time to engage in creative cooking with a much smaller number of ingredients, make music, make love, and play with the kids and the dogs.

In short, back to idyllic Medieval Europe, the sort of thing they show in dioramas and "intentional communities."

Was it ever this nice?

No, the Black Death intervened.

Normalized Oil Consumption (100 = 1998, EIA) for the US and Four Developing Countries, 1998 to 2009:

From 1998 to 2008, average annual US spot crude oil prices rose at 20%/year. From 1998 to 2009, they rose at 14%/year.

If we extrapolate the 2005 to 2009 rate of increase in Chindia's net oil imports, they would be consuming 100% of global net oil exports sometime around 2025.

Interesting coincidence that if we extrapolate the 2005 to 2009 rate of decline in the US petroleum C/P (Consumption/Production) ratio, the US would approach zero net oil imports around 2024 (C/P ratio of 100% indicates zero net oil exports and zero net oil imports):

In any case, as they say, somethings gotta give, and right now it's hard to tell what. But a safe assumption is that the outlook for the US economy is less than rosy.

With the US trade deficit running over $500 billion / year, and oil imports running on the order of $1 billion / day, it is only a matter of time until US oil imports have to go to zero. 2024 is as good a year as any other, although I would think it would be sooner.

Besides economic recession, changes in international finance and geopolitics are also foreseeable.

Japan, which had recently fallen to third place in the GDP tables, is likely to continue to decline as a result of the earthquake/tsunami/reactor disaster. The US is in no position to bail out Japan with cargos of oil and gas, or to assist Japanese reconstruction in any meaningful way. Japan is somewhat in play and will likely move towards closer integration with Southeast Asia, China and the Russian Far East.

The Middle East situation has gotten beyond the ability of the US to control events. If democratic forces succeed, the result will be more energy consumption at home, higher prices for oil exports, and less friendly relationships with the US and its allies in the region.

Post USSR, the US's approach has been to expand NATO and to prevent any rapprochement between Russia and Europe. However, it is clear that Central and Eastern Europe's best hope for energy security is to achieve some arrangement for energy supplies from Russia, Central Asia and the Caspian Sea states, including Iran. These supplies should be overland or via the Black and Mediterranean Seas, and they should avoid transiting the Persian Gulf, Indian Ocean and Red Sea.

NATO meanwhile is proving to be unresponsive to US and UK direction with respect to Libya -- its expansion has resulted in a "talking shop". The Eurozone has its own problems, specifically Ireland, Portugal and Greece. It is notable that these problem countries all have long historic ties to the UK, and Anglo-America style banking and finance was part of the cause of their financial woes. The Eurozone needs to reorganize its economic structures on sounder principles, and it may need to eliminate some recalcitrant members.

The trilaterlist's troika of New York, London, and Tokyo continues to decline in the face of new international finance centers and new geopolitical events.

I'm pretty much up to here with all the economic disaster starts at $XXX a barrel or XX million barrels/day of production. There is no physical reason why the current global population can't do just fine of half of that. Or less. And none in the long run.

Assuming that the costs of production go somewhere, the money isn't lost and increased production expenditures add to GDP. As one wag pointed out, in our culture a heart bypass is seen as a drain on the economy while a facelift is economic growth.

Granted, given our current state of organizational paralysis and lack of foresight, oil price 'spikes' do create recessions. Then we wait for market forces to do their thing and go back to doing the same stupid stuff with the same organizational model as before.

If we took a fraction of the amount of real capital we can deploy - human endeavor currently sidelined by unemployment of engaged in non productive crap games - and got on with alternative energy and efficiency projects we wouldn't need the article.

Almost all of the US building and housing stock is obsolete and functionally worthless; indeed, all of the houses built during the recent boom are useless crap in the long run yet somehow we can't figure out how to put any significant fraction of the money expended and labor consumed into things like the power grid or CSP plants. Never enough money to do it right but always money to do it over - and wrong again. Instead of millions of excess houses in abandoned subdivisions we could have had......

The only recession is in our inability to conceive of an economic and organizational system that could actually efficiently utilize our endeavors for our mutual long term benefit. We're still making cheap crap to fall apart and require replacement to keep churning a 'vig' to capital, yet have no national railway system [horrors!; socialism] yet somehow an interstate highway system.

So whenever I hear that we can't do X because of a recession I have to point out that until we haven't any more serious work to do the blame lies with the publics own gutlessness at tolerating an organizational system that is run by grifters and liars and sycophantic idiots who haven't realized that the parasite has almost devoured the host.

Then it will be 'Who knew?' time.

To be fair, I don't think the public is given an alternative by any parties, but I agree with everything else.

Alternatives aren't usually given or offered but rather demanded or just taken. Thus the question becomes at what state of disfunctionality the citizenry decide to actually get involved in their long term future and whether sufficiently robust and competent organization can be maintained long enough to achieve anything.

The current Tweedledee/dum two parties system is so firmly entrenched that there is no word for tripartisanship. Or quadpartisanship. Say what?? So we're either with them - or the other them. And each election is a tale full of sound and fury.

Canada currently has "quadpartisanship", and it does not necessarily create any better results, especially since the Westminster system, which both countries use, is really meant to be a two party system.

The more parties you have, the more you tend towards minority governments, which, by definition, do not have a strong mandate to govern. In systems like Canada, this leads to frequent and unnecessary elections - minority government was defeated last Friday so now we get the 4th election in 7 years, and likely to result in another minority! In fixed term systems, minority situations often render the government impotent for the whole of the term.

The more parties, the more they each represent specific minority groups (e.g. the Quebec separatists), and the more pandering that has to be done to get them on board -though they can still turn on the gov at the drop of a hat.

Ultimately, it is up to the people, collectively, to demand better government - having more parties involved is no guarantee of getting it, and often makes it worse.

Just a short look outside the US. Using the oil export browser and Wikipedia GDP data, plus a danger threshold of 5.5% of GDP spent on oil, I get an oil price recession threshold of

$107 per barrel for the USA

and

$214 per barrel for France

Interesting!

If US oil consumption per capita fell back to our 1949 rate (EIA) it would still be higher than France's 2005 per capita consumption rate (Nationmaster).

I am not sure that you can extrapolate the US results to France. This is link to a site showing France's real GDP growth by quarter. It looks like they had recession in 2008-2009, too.

There is also an issue of "wholesale" vs "retail" calculations. Different people have done the calculations on a wholesale price basis vs a retail basis, and gotten different percentages, but similar dollars. It is possible you are mixing apples and oranges in your comparisons.

Yeah France had a recession too but I think there is some truth to the point that France's economy is more resilient to high oil prices. Their land use and transportation patterns are much more energy efficient. People can still get to work without driving if they have to. They have a more robust local agriculture.

The US has none of these things. Yet our consumption has propped up the world's economy for generations. When we go down everyone else will go down too, but other countries will have a shorter fall to the bottom than we will.

I think it is fair to say that most OECD countries experienced a recession, or at least a plateau, in the last couple of years.

But what I find interesting is that this seemed to happen regardless of their oil consumption. Canada uses as much oil per capita (and more per GDP) than US, but had (has) a much less severe recession. The euro countries use half the oil per capita, and they all had recessions, to varying degrees. Australia is somewhere in between, and had a flattening of growth,but not a real recession, and is well out of it now - regardless of oil prices.

So while oil prices may trigger recessions, it seems that other factors, mostly domestic, determine, or at least majorly influence, how deep/long they run.

That said, I'm all for using less oil, regardless

OIl usage kept going up in China, India and quite a few oil exporting nations. They didn't have recessions.

China uses mostly coal, rather than oil, so it was less affected. Oil exporting nations generally don't charge their own people the high prices that outsiders pay for oil, so their own people don't ever see the high prices, perhaps explaining the lack of cut back.

Quite so - that is why I was only considering the OECD economies, which I regard as "mature" economies, but China and India, and most of the oil exporters, are certainly not. And the China/India oil/GDP is certainly much lower then OECD.

But among the OECD group both UK and USA have severe recessions, but UK uses half the oil/capita. Mind you, with the very high fuel taxes, making the pump price double the US -the $ spent per person on fuel might be similar, with similar results on discretionary spending.

In any case, the depth of (OECD) recessions does not appear to be solely linked to oil/capita or per GDP, though the timing certainly is.

Hi Paul. I think that Australia has a unique position in what has unfolded during the recession. Australia has enormous reserves of industrial raw materials, particularly coal and iron ore, that are in high demand from China. China has maintained growth and continues to demand these raw materials. Just how much China needs was illustrated by the impact of the mine closures in Queensland as a result of disastrous floods early this year.

Great article Gail, fascinating thread Oiler's.

Thai,

i would agree with that assessment 100%. Australia has real materials to sell that are in real demand, so has dodged the bullet. Canada has real materials to sell, and got off almost as lightly as Australia. The US has to sell - well, treasury bonds!

It would be nice if Australia did some value adding instead of just shipping the raw commodities as soon as they are dug up - but China does that part cheaper than Australia, or anyone else...

This was indeed a good article and discussion. I am going to send it to my contact in the Australian government.

In order to add value, you would need a larger workforce necessitating a larger population. From what I have seen, the Australian government does not want the population to rise too much more than what it is right now. Alternatively, they seem to be content exporting raw materials with a smaller population.

n order to add value, you would need a larger workforce necessitating a larger population.

Not necessarily. Converting iron ore to iron, or NG to ammonia/fertiliser, or bauxite to alumina to aluminium are all high energy, high capital, low labour operations. Australia has lots of energy, capital, and a skilled workforce. Going further than iron to making widgets from it is a whole differrent story, and is not likely, more for the labour cost than the population issues.

Making widgets is tough, because you never really know if your widget will still be needed in the future, and someone else can copy the design - stealing/devaluing the IP. But iron, fertiliser and aluminium will always be needed, and there is no IP to steal in their manufacture, be, so we might as well turn the raw commodity into the upgraded version, then let others take it from there - Australia does largely do that with bauxite-aluminium.

As for population, yes, there is no real need to grow it - some are of the opinion that pop growth in and of itself will grow the economy, and it may, but there are other, better ways to grow the economy too. There are some limits, particularly fresh water, on how many people can comfortably live in Australia.

Gail,

while it is true that discretionary spending declines the increased investment for producing the energy also provides economic support- Consumption plus investment doesn't change so neither does economic growth.

It seems to me that there is a difference between low cost oil sold at a high price with the funds received by the oil producers deposited in a bank and high cost oil sold at a high price. The former situation hss a handful of very large winners while the latter creates both large winners and losers -great for people living near or associated with oil production and so good for consumers who have to drive a lot but whose wages are not going up.

If I am right then perhaps higher oil prices because of higher costs of production doesn't result in a recession. The date points for co-relating recessions and oil prices all relate to low cost oil sold at a high price.

"Consumption plus investment doesn't change so neither does economic growth."

Crazyv, thanks for pointing out the enormous flaw in the logic of economists. You really think that whats going on Fort McMurray, Alberta is sustainable economic growth, equal to the growth that would have occurred if oil prices were low and consumers could still drive, shop, visit tourist destinations etc? Well thats what our current method for calculating GDP would tell us, and its f-ing crazy.

I live in Western Colorado, an area where there is a lot of expensive oil and gas being produced, where in theory it should return wealth to the local economy. In the long run its a disaster for the local economy. The only people it enriches are a few local landowners (the old boys club) and a bunch of roughnecks from Louisiana who have the side benefit of making our town unlivable for anyone else who would like to add longterm economic value. And then the bust will come, landvalues will bust, and the region will have put all our economic eggs in the oil and gas basket, and we will be mired in (another) localized depression for the next twenty years. All this boom/bust cycle does is redistribute wealth to the top 3% of society and those most willing to cut corners and rape our local land and water, throw up crappy subdivisions, and discourage any stable economic forces from coming in. But hey, its all economic growth!!

You are forgetting about the declining EROI issue. There is less net energy being produced, with the same number of real dollars. And it is net energy, particularly high quality net energy, that determines real output. Economists don't seem to think that net energy is important, but it is very important. In a way, it means that $$ spent for investment now provide less real benefit now than they did in the past.

When people pay a higher price for food, it goes for a higher price for fertilizer--same amount of food, and same amount of fertilizer, but more money needs to be invested to get the same amount of fertilizer. There are people paid more wages, but there is not more fertilizer produced or more food produced, just more inflation, because of the lack of real improvement in output.

So with lower EROI, what we get is inflation (at least in oil, food, and energy intensive goods). People are forced to cut back on other goods, causing recession.

I suppose a person could develop a model of a world with only three goods: oil (used to produce food and widgets), food, and widgets. As more and more labor and capital are required for oil production, less oil is produced for a given amount of investment. In order to get adequate food output, a high proportion of the oil must be used for food production, leaving less for widget production. Workers may be paid the same amount, but what they end up purchasing is a similar amount of food (because this is a necessity) and less widgets. The result looks like food inflation to the worker. (I am assuming the worker is not buying oil.)

So what exactly are the OP's and commenters' predictions for oil prices over the next 20 years? As I read the OP, she seems to be saying prices won't go very high because as soon as the price increases some the world will go into recession and bring the price back down.

I disagree. I still think prices will go to the moon. Oil prices are set internationally. The increase in demand from China, elsewhere, population growth and the declining supply will overwhelm any recessionary effects (although prices will go up in a fashion of two steps forward and one step back).

pasttense,

I used to agree with you, but have since come to believe that the enormous debt burden that banks and governments have leveraged on our wealth will precipitate a more serious collapse. Its the oil problem PLUS the debt problem that will be too much for China's momentum to overcome. China's growth is dependent on the over-leveraged American consumer, so they are just as screwed as we are.

Without the debt explosion of the last 25 years (it really started in 1986) you are right, oil prices would go two steps forward and one back. Then again, all that debt explosion is what allowed us to use so much oil so fast in the first place, so prices would probably be lower now and peak oil would be put off another ten years.....

Anyways.....I think if the only problem were peak oil, civilization could over come it. If the only problem were our debt burden, we could muddle through and fix our financial system. Put the two together and its pretty tough. Overhauling our energy system's infrastructure would require a lot of debt, and we just don't have the wiggle room we need (thanks G.W. Bush for the tax cuts and wars!)

It is a mistake to assume that China is still dependent on America to drive it's economy. The continued Chinese auto sales growth is an example of strong domestic demand. They will also be ready to supply the products which Japan will be unable to deliver due to their crisis.

It seems possible that the Chinese RMB may increase in value. Then their cost would remain the same even as the dollar value of the oil price goes higher. We will be outbid for the oil in the open market IMHO.

One person’s / entities debt is somebody else’s asset.

Rgds

WeekendPeak

In many cases, they are assets of insurance companies, pensions, or banks. If people don't pay back the loans, our financial institutions are "toast".

I am doubtful that our current financial system will last for 20 years, so I am not sure there is a real answer to your question.