EROI, Insidious Feedbacks, and the End of Economic Growth

Posted by David Murphy on September 17, 2010 - 10:16am in The Oil Drum: Net Energy

The following is a brief portion of a paper of the same title that we (Charles Hall and I) wrote and that is currently under peer-review. I will be presenting on this topic at this year’s ASPO conference in Washington, D.C. I hope that our readers will attend!

Numerous theories attempting to explain business cycles have been posited over the past century, each offering a unique explanation for the causes of--and solutions to--recessions, including: Keynesian Theory, the Monetarist Model, the Rational Expectations Model, Real Business Cycle Models, New (Neo-) Keynesian models, etc…

Yet, for all the differences amongst these theories, they all share one implicit assumption: a return to a growing economy, i.e. growing GDP, is in fact possible. Historically, there has been no reason to question this assumption as GDP, incomes, and most other measures of economic growth have in fact grown steadily over the past century. (Note: economic growth and “business as usual” economic growth are used synonymousy to mean an annual growth in GDP)

But if you believe as I do that the world is entering a unique period defined by flattening and then declining oil supplies, then for the first time in history we may be asked to grow the economy while simultaneously decreasing oil consumption, something that has yet to occur in the U.S. In this post I attempt to answer the following question: Is a return to long term economic growth possible?

Economic growth over the past 200 years has correlated highly with energy consumption (Figure 1). Even more telling, since 1970, 50% of the year on year change in GDP in the U.S. is explained by the year on year change in oil consumption alone (Figure 2). This is important because oil consumption per se is rarely used by neoclassical economists as a means of explaining economic growth. For example, Knoop (2010) described the 1973 recession in terms of high oil prices, high unemployment and inflation, yet omitted mentioning that oil consumption declined four percent during the first year and two percent during the second year. Later in the same description, Knoop claimed that the emergence from this recession in 1975 was due to a decrease in both the price of oil and inflation, and an increase in money supply. To be sure, those factors contributed to the recession and the emergence from the recession, but what was omitted, again, was the simple fact that higher oil prices led to less oil consumption and lower economic output during 1973 and lower oil prices led to increased oil consumption and hence greater economic output in 1975.

Figure 1. Energy production and GDP for the world from 1830 to 2000.

Figure 2. Correlation of YoY changes in oil consumption with YoY changes in real GDP, for the U.S. from 1970 through 2008. (Oil consumption data from the BP Statistical Review of 2009 and real GDP data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve.)

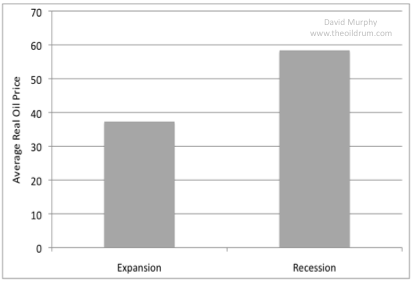

As this example indicates, it is not just simply having access to energy per se that causes economic growth, rather the energy must be accessible cheaply. For example, the inflation-adjusted price of oil averaged across all expansionary years from 1970 to 2008 was $37 per barrel compared to $58 per barrel averaged across recessionary years (Figures 3).

Figure 3. Real oil prices averaged over expansionary and recessionary periods from 1970 through 2008.

To summarize: economic growth requires not only energy per se, but inexpensive energy.

With that point in mind, we can address the previous question about whether or not a future of long term economic growth is possible by answering two sub-questions: 1) do we have the physical resources to supply a growing economy, and 2) can we reach those supply targets while maintaining a low price? Since long term economic growth requires an increasing supply of cheap energy, answering no to either of these sub-questions would indicate that long term economic growth is unlikely.

First, economic growth requires increasing oil supplies, so increasing GDP by 4 or 5 percent per annum will require a commensurate increase in oil supplies. Although most of the readers on this website are aware of Peak Oil, some argue that it is a red herring. I will not go into the numerous arguments rebutting the naysayers other than saying the following: what matters in the context of business as usual economic growth is whether we can continue increasing our oil supply into the future or whether oil supplies will be constrained. In this context, the actual date of the peak is irrelevant. Even a cursory examination would reveal that, at a minimum, oil supplies will be constrained in the future.

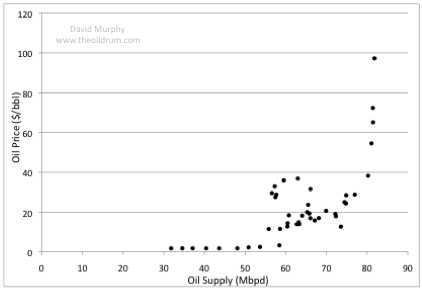

Second, increasing the supply of oil will require maintaining current production and discovering new sources of oil. This includes maintaining production in oil sands, exploring ultra deep water, and exploring even the poles. Let’s say, for argument sake, that we are able to find oodles of oil in these locations. The question then becomes: can we produce this oil cheaply? We can get a glimpse at how production costs change over time by relating the EROI of production to the financial cost of production (Figure 4). As resource quality declines, i.e. lower EROI, the cost of producing the resource increases. Alternatively, if we examine a supply graph for global oil production we can see an interesting relation between quantity and price (Figure 5). Both of these figures indicate that increasing oil production much beyond today’s level will create an exponential increase in price. In sum, increasing the oil supply, if in fact we can do such a thing, can occur only at high oil prices.

Figure 4. Oil production costs from various sources as a function of the EROI of those sources. The dotted lines represent the real oil price averaged over both recessions and expansions during the period from 1970 through 2008.

Figure 5. Real oil prices plotted as a function of global oil supply from 1970 through 2008.

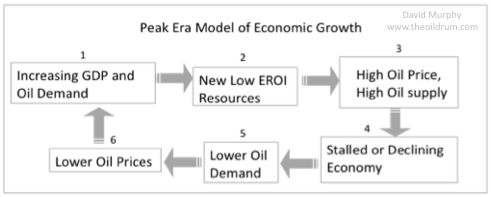

Due to the depletion of high EROI oil (and hence cheap oil), the current economic situation can be described by the following feedbacks (Figure 6): 1) economic growth increases oil demand, 2) higher oil demand increases oil production from lower EROI resources, 3) increasing extraction costs leads to higher oil prices, 4) higher oil prices stall economic growth or cause economic contractions, 5) economic contraction leads to lower oil demand, 6) lower oil demand leads to lower oil prices which spur another short bout of economic growth until this cycle repeats itself.

Figure 6. Peak era model of the economy.

This system of insidious feedbacks is aptly described as a growth paradox: maintaining business as usual economic growth will require the production of new sources of oil, yet the only sources of oil remaining require high oil prices, thus hampering economic growth.

The growth paradox leads to a highly volatile economy that oscillates frequently between expansion and contraction periods, and as a result, there may appear to be numerous peaks in oil production (a so-called "undulating plateau"). In terms of business cycles, the main difference between economic models of the past and the this model is that in the past business cycles appeared as oscillations around an increasing trend whereas in this model they appear as oscillations around a flat trend. In other words, our baseline economic models may be switching from an implicit 1 or 2 percent growth to a steady-state, or dare I say, declining trend.

So arguments that cite vast oil reserves 10,000 leagues under the sea or in the poles as evidence that peak oil will not matter need to realize that in terms of economic growth, oil per se isn’t enough. Cheap oil is needed for economic growth, and we are simply running out of the good, cheap crude.

I would be inclined to agree with the statement "cheap energy is needed for growth" but the statement above is too simplistic. And I can't tell whether the argument given is supposed to apply to the US only or to the world as a whole.

In general, I love the idea of looking for patterns in the following kinds of scatterplots

Patterns always emerge and they have huge explanatory power.

But doing this only for the world as a whole and only for one energy resource is like painting your canvas with a roller and only one color -- the real world has much more variation than is depicted here.

Fuel-switching does happen and is well documented in the historical record in various countries.

I cannot say much more than that as I have not found a good, historical dataset with international GDP numbers to use in a databrowser. But I'm sure that plots generated on a country-by-country basis would reveal a variety of patterns and the fun would begin when we try to explain the differences.

The world is a very heterogeneous place and response to fossil fuel shortages will be equally varied.

Jon

Johnathan Callahan,

You are correct in stating that this is a generalized piece based on a more complex issue. However, none of the arguments I present are flawed in any major way. Fuel switching, or 'substitution,' can and will occur over time. But the problems presented by peak oil are more than just substituting at the margins, i.e. natural gas fired electricity for older coal generation. We are talking about substituting for an entire primary energy source, something that Marchetti (1977) examined. He found that substituting for primary energy takes a very long time - upwards of a century for a new energy source to replace 50% of market capacity of the older source. Hirsch (2005) has also spoke about the time it takes to replace infrastructure.

Marchetti. 1977. Primary Energy Substitution Models: On the Interaction between Energy and Society. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 10: 345 - 356.

Hirsch, Bezdek and Wendling. 2005. Peaking of World Oil Production: Impacts, Mitigation, and Risk Management. SAIC. 1 - 91.

David,

I do in fact agree with your overall logic and assessment that we are likely to see a "highly volatile economy that oscillates frequently between expansion and contraction". And, of course, liquid fuels have a special importance because of their dominance in transportation.

So please consider my comment merely as a suggestion for a more nuanced approach in the text and perhaps an examination of how some individual nations have dealt with decreased access to petroleum products. Economic (or political) duress can speed up the fuel-switching process as seen in Iran which was forced to switch from 80% dependence on oil to 40% dependence in just 30 years. (Still a long time!)

I have no doubt that increasingly expensive liquid fuels will wreak economic havoc throughout the industrialized and developing world. I just think it will play out very differently in different nations depending upon several factors:

Clarifying that your approach applies particularly to the US or to all OECD nations is all I am suggesting.

Best Regards,

Jon

Johnathan,

Your comments are appreciated, understood, and on-point. thank you!

Dave

These graphs are excellent to a point. They don't really show substitution though. They only show that the use of gas increased relative to oil. This could mean that oil went down and gas went up, it could mean that oil use was flat and gas went up, or it could be that oil use is up and gas is up. I'd guess it is the latter. So...good stuff, but it would mean more to include absolute numbers.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2d/ELM_Iran_Oil.png

I don't know the particulars, but I would expect that oil use to generate electricity has gone down in absolute terms, and likely been substituted for with gas....but overall consumption has increased.

-dr

The Energy Export databrowser has several plot options which allow you modify the appearance of the plots. Here is the plot you are asking for:

So you are absolutely correct that "oil use is up and gas is up" -- both dramatically! Iran didn't actually switch in terms of amounts. But they did rework their economy so that growth now comes primarily from gas rather than oil.

A better example of actual fuel switching would be Denmark, where total consumption of oil has decreased by more than 50% since 1972 and where total energy use from fossil fuels has actually gone down every year but two since 1996.

You may find other examples that show various degrees of fuel switching if you poke around in the databrowser.

Happy Exploring!

Jon

For starters:

Now on what basis would you conclude that: since 1970, 50% of the year on year change in GDP in the U.S. is explained by the year on year change in oil consumption alone when it is at least equally logical to conclude from the evidence that it is the change in oil consumption which is explained by the change in GDP?

I see money supply gets a passing reference in your unflawed-in-any-major-way arguments. Why don't you attempt to control for money supply in your effort to show that correlation is causation (and that your view of what is cause and what is effect is the correct one)?

And on the subject of money and its circulation through the economy, why haven't you examined the international financial architecture during the periods in question from the perspective of the role played by structural impediments to the recirculation of petrodollars?

You have chosen to believe the simple fact that higher oil prices led to less oil consumption and lower economic output during 1973 and lower oil prices led to increased oil consumption and hence greater economic output in 1975. "Led" in this context implies causation, and while there is ample evidence that price affects consumption, there is only your assertion and that of like-minded 'believers' that the change in oil price was anything more than a barely proximate contributing factor to the changes in economic output.

Toilforoil

I did not include this in the post, but it is in the longer paper that is currently under review. There has been a myriad of work done on the nexus of income and energy. Much of the literature is confounding - see Karanfil (2008). However, amongst these studies there is clear trend in causation from energy to income if the quality of energy is accounted for. I direct your attention to Cleveland et al. (2000).

Cleveland, Kaufmann and Stern. 2000. Aggregation and the role of energy in the economy. Ecological Economics, 32

Now on what basis would you conclude that: since 1970, 50% of the year on year change in GDP in the U.S. is explained by the year on year change in oil consumption alone when it is at least equally logical to conclude from the evidence that it is the change in oil consumption which is explained by the change in GDP?

This. A thousand times, this. Which is cause and which is effect? It's accepted gospel here on The Oil Drum that it's oil availability that drives economic growth rather than the other way around, and personally I agree with the idea in the long term, but we need to recognize that oil and the economy are linked in a complicated 2-way feedback where each controls the other.

The above article contains zero information to distinguish cause from effect. And unlike other fine articles here on ToD, it doesn't even recognize that this is an issue to be dealt with.

One final criticism: the statistics are biased by the long-term trend. When considering bulk human statistics, the problem is that "everything goes up": a graph of global chicken population vs global GDP would give similar numbers ... but nobody believes that chickens are the primary driver of the economy! To partially but not totally ameliorate this problem, use per capita statistics.

please see my response to ToilForOil above.

David

Great concise summary of a complex subject. Looking forward to hearing your talk in D. C.

Link to Marchetti article:

http://www.cesaremarchetti.org/archive/scan/MARCHETTI-007.pdf

That is a key observation which spoils some of the doomer fantasies.

We could well see many geographical areas which ride out global energy shortages very well for decades or even centuries.

I can imagine islands of advanced technology in an ocean of poverty .... err, a bit like the present world I suppose, but with a much greater percentage of the population in the poverty camp.

At some stage there will be a big push to develop energy efficient technologies : the countries & people which can design / build / operate these technologies will be at the top of the pile.

The transition could however be painful as town after town in the West slides into third world status, with only the university towns and similar privileged areas maintaining a decent standard of living.

"spoils some of the doomer fantasies"

Only if you can be sure that you will be on one of the islands of (relative?) non-doom.

But that I guess is the point. He said:

Another way of saying this is that the world is not deterministic, and that different regions will play out at different rates. One of the big problems with the LimitsToGrowth system dynamics model is the level of determinancy that it demands.

This points to the rationale for the dispersive discovery model and why the logistic Hubbert peak profile is better understood by considering randomness and dispersion rather than by some deterministic birth/death equations.

Until people understand this stuff, we will have doomers continue to think that things will fall off a cliff. We aren't necessarily close to being reindeer on an island or a culture in a Petri dish.

WHT,

As many folks like the "fall off a cliff" image perhaps we should promote another climbing metaphor that captures non-deterministic, dispersive behavior?

May I humbly suggest that modern society is not about to "fall off a cliff" but instead "tumble down a scree slope" with all the stops and starts of aangel's stairsteps.

We're quite sure of the direction of travel but the speed and distance traveled, the number and length of pauses and the cumulative injuries experienced on the way down will be different for different members of our party.

Best Hopes for picking a path with a decent runout.

Jon

That's a better metaphor. The other analogy to introduce is that you can't continue to build a plateau on a scree slope by piling up bits of rubble. There will be a steeper decline at the point where the plateau can no longer support itself, i.e. technical improvements can't keep pace.

Straining for metaphors of course, but most of these dispersion arguments come from known solutions to classical physics problems such as diffusion and convection as well as thermodynamics of course.

My metaphor is a forest fire.

While it would be insane to deny the forest fire there will be regions that fare better.

Perhaps Bob Mugabe was inadvertently picking the least worst course for his nation, Zimbabwe, when he pulled the plug on the industrial experiment, causing the population to prematurely crash to sustainable levels.

Concerning the "Doomer fantasy" epithet all predictions are mental constructs and are therefore by definition fantasies.

That regrettably is itself a fantasy.

It helps to allay the perhaps premature "prediction" about your (and my) mortality.

___________________________________

"Even the immortals must die" --Eric Nortman (True Blood)

That is certainly comforting, thank you.

It sounds like a classic distinction without a difference.

Perhaps you've never been climbing?

I'll take "tumbling down a scree slope" over "falling off a cliff" any day.

Best Hopes for safe climbing practices including map and compass skills -- it's important to know the terrain ahead.

Jon

We have certainly already pushed the rest of the living world down a very steep scree slope, and perhaps a bit of a cliff.

I actually consider myself a bit beyond "doomerism," since this usually is predicting impending doom, and I consider us already deep in the belly of doom. The sixth mass extinction has been going on for some time now, even before the effects of GW had really gotten going.

I don't think we can absolutely rule out any kind of future black swans or "discontinuities," in fact some are virtually guaranteed--it is just a bit difficult to get their exact timing and magnitude right.

Yes, I like university towns too and I even live in one. However, it is hard to imagine a really huge gap existing between such towns and the rest of the country - at least not much more of a gap than at present, and the present gap is at least partially a matter of aesthetic preference, more than it is absolute wealth.

But a truly wide gap would quickly be narrowed, as it always has been, by human migration. Just look at the southern border of the USA. In theory, it is strictly controlled by one of the richest, most technologically advanced nations in the world. But in practice, there are many industries that depend on a sub-minimum wage labor force that works hard and never complains. And even upper middle class families enjoy the really cheap gardeners and maids. They may vote conservative, "but Maria is really like part of the family, and she even babysits for us" (at $3.50/hour). Recent Federal Court nominees have spilled that little secret for all to see.

So unless these "privileged areas" become like walled medieval towns, there will be plenty of hopeful visitors and new neighbors from the 3rd world areas (and they will probably arrive even with the fortress walls) and then before you know it, "there goes the neighborhood".

Yair...

"The transition could however be painful as town after town in the West slides into third world status, with only the university towns and similar privileged areas maintaining a decent standard of living."

I don't think the university towns will be priviledged areas...you will need to know real world stuff like how to pluck a chook or dress out a kangaroo/deer.

Very good.

This article is consistent with what I have been trying to explain to my own circle of family and friends.

And my gut feeling has been that $75 oil is too expensive for the maintenance of a non-recessionary, growing economy. It only being a matter of time before $75 oil forces us into another leg down.

But, my question is, are the figures cited above adjusted for inflation to today's dollars? I mean the below $40 oil needed for growth and the over $40 oil ultimately leading to renewed recession. Or, is $75 oil, after adjusting for inflation, still within the "safe zone" permitting economic BAU?

Jabberwock,

Everything is inflation-adjusted - both GDP and oil price numbers.

Thanks, David.

I prolly shoulda' deduced that;-)

Mr David MURPHY,

I suppose you are well named, considering your subject matter. ;)

As I see it, there is no way, theoritically, to prove that we can't have a growing economy with a shrinking oil supply, as the answer depends on the asumptions made both pro and con.

As a practical matter, I also see a lot of stuff held up as "proof" by economists as merely good indicators of likely outcomes, were history to repeat itself.

An economist would look at five or six plays run successfully, or unsuccessfully, by a football team, or even three or four plays sometimes, and draw sweeping conclusions about the effectiveness of certain defensive or offensive strategies, where as even a junior high school player would understand that dozens or hundreds and thousands of other factors must be considered to accurately evaluate what happened during those few downs.

As a practical matter,I do not doubt that a shrinking oil supply means a shrinking economy, and that the shrinkage will continue for a very long time.

Large elements or players, physical and cultural, are so tightly embedded in our economy that we might as well regard them as builtin or structural-the automibile industry physically and the driving habit culturally;the people and businesses involved will fight a viscious rear gaurd action as they see thier livelihoods and life styles beginning to disappear;this will slow down any transition to mass transit by decades at least.

I am sure you and many others can think instantly of many other examples of a similar nature;change is not dependent on mere technological progress.

But I have not seen a good argument made by anybody to the effect that once we hit bottom on the oil supply, the economy cannot begin to grow again, this of course after Mr Malthus finally gets his long overdue the last laugh.

The post oil economy probably won't approach the size of the current oil based economy for centuries, if ever, but there is no way to know that for sure.GDp is a truly rotten metric anyway, and we should be measuring the economy on a quality of life basis instead.

If culture changes such that people invest a much larger portion of thier disposable income in long term capital type goods(people who don't see houses as investments are intellectually blind to the fact that a house provides a steady but non cash income stream to its owner occupant) such as building and improving a truly "built for the future" house, they don't need to travel so much to have an equally desirable life.

Since our family home is provided with a swimming pool, a masonry storage barn, nice landscaping, a glassed in porch,lots of outside recreational areas, and so forth, we are happier than many people with far more money living in far more expensive places;and although we never have had much money, we were able to fix this place up the way it is simply by forgoing some other consumption-such as by driving one new truck into the dirt every fifteen years instead of trading every few years for a new one.

I don't belive that new tech can save us from a long period of decline, as there simply does not appear to be time for such tech to be invented, commercialized, and built out before the oil issue knocks us on our collective economic butts.

But otoh, there is no reason to think that technological progress will come to a halt, either,over the next century or two, unless we descend all the way back to a stone age.

Even very expensive , scarce renewable enery can provide us with a very comfortable lifestyle, if we are willing to give up our current habits.

The amount of money most middle clas people pee away on UNNECESSARILY expensive automobiles alone-( often hundreds of thousands of dollars over thier working lives) would be more than ample, if added to thier housing budgets, to put them into zero net energy houses, using todays existing technology. HOUSES CAN BE LEFT as gifts TO CHILDREN OF COURSE , and often are-depending on the culture involved-in exchange for helping look after the elderly who after all, are soon enough departed.

We can garden for exercise and relaxation instead of playing golf, bicycle locally and swim in a community park instead of hopping a jet to Colorado.

Is this growth?

I guess it depends on the way you define the word.

The only real difference, in the grand scheme of things, is that it will probably never be as fast as the growth experienced during the oil era.

Excellent points. Let us avoid knowing the price of everything and the value of nothing. We innumerati might value a bus trip to a concert in Millenium Park (in Chicago) more than a trip to the mountains, but our present pricing mechanisms are incapable of registering this.

The only snag from a policy standpoint is that within the range that, realistically, we're probably discussing, "quality of life" is so utterly subjective. (And we wouldn't be bothering to discuss this if it had no policy implications.) Thus, we might poll people every so often and ask them whether said "quality" is getting better or worse. But that would provide little or no guidance about how to improve matters, since there are so many possible reasons for such perceptions. So we might in addition ask them what changes they might see as offering better quality - and get a bazillion incompatible answers, pointing in every direction on the compass, as well as more than a few directions completely off the compass.

So, in the real world, we must try something else entirely, lest we become utterly lost in a muddle. Most of the time, we follow a standard procedure:

(1) a self-appointed absent-minded professor (or committee of professors or pollsters) creates a random list of possible characteristics of a region, which will serve as a tractable stand-in for characteristics of a lifestyle.

(2) said self-appointed professor(s) assign each chosen characteristic a coefficient ex cathedra - so many points for "free" medical care, so many points for narrow streets, so many points for bus service never mind whether it runs on time, so many points for access to "nature", etc. etc. etc.

(3) their grad students compute scores for a set of regions.

(4) finally, in the manner of "the idiot who praises, with enthusiastic tone/ all centuries but this and every country but his own" (link) the professor(s) declare that country X (where X must be the USA or another developed country, never some oppressive, violent 'third-world' hellhole) is an abomination, or at least deliciously wicked.

Unfortunately, this process tells us a great deal about the quasi-religious whims and biases of the professor(s), and nothing whatever about the desirability of living in country X. After all, one person's greater "quality" is all too often another person's lesser "quality", vide, say, the arguments over

suburban cul-de-sacsjust about everything. Once we get beyond a handful of "obvious" characteristics that "everybody [supposedly] agrees on", we're lost, we've got no sound basis to assert that there's anything more we can really measure with any stable or universal yardstick.This seems to leave us in much the same quandary as the drunk looking for the glasses by the lamppost. True enough, the glasses aren't actually by the lamppost. OTOH not much use looking out in the darkness since one couldn't see them even if they were there.

In the case at hand, another pair of glasses happens to lie conveniently near the lamppost - GDP. Maybe it's not quite precisely what we were after, but at least it measures something. And that something does tend to correlate positively with subjective expressions of the elusive concept of "happiness" even if the correlation declines with increasing income.

In other words, we seem to be stuck with GDP because any other measure ensnares us in endless bootless arguments of a quasi-religious nature (arguments of the sort that, for example, the framers of the First Amendment wisely chose simply to sidestep) - many of which may never be widely or broadly settled.

Good points. I would only differ in saying that GDP is no less "quasi religious" than any other measure--it just seems less so (to some) because they are used to it (or are so far inside the 'religion' that it looks like God's Truth to them).

Because it is not easy or clear is no reason not to seek to improve our models.

I believe you are grossly misrepresenting the formation of modern GPI (Genuine Progress Indicator) systems. Rather than being based on characteristics and weightings chosen by some "self-appointed professor", institutes are much more likely to actually survey the public about what THEY value. The resulting rankings are thus far more valid than your description would indicate, and represent how the public feel their quality of life is, and how it is trending.

Plus, those studies generally show that the US and other developed nations have a pretty high quality of life, but it is not clearly linked to GDP - does not grow as quickly, or may plateau or even drop as GDP grows beyond a certain point. Not quite a "wicked abomination", but perhaps it comes across that way to anyone who is dead certain that GDP rise must always = general life improvement.

On the other hand, there are some real questions about the accuracy of aspects of GDP, and even more about how appropriate it is as any kind of progress measure once it exceeds somewhere around $10,000 per capita.

Nothing worthwhile is being said here, because it is never acknowledged that the general population has little to say about how it decides its gut feelings about quality of life, and if they were to do so, it would merely launch another corpocracy media assault on their feelings.

As is obvious from cultural anthropology, quality of life, or distance from revolution, to be accurate, is not even minimally linked to GDP, but rather to conformance between what is expected, and what is received (crisis of rising expectations).

I think modern perception-molding techniques are more than capable of making people happy with whatever the corporate masters need, including less travel, smaller houses, plainer food, less education (pointy-headed professors, above) and shorter lives. Medicine can treat symptoms instead of causes, and TheOilDrum can fritter away time exploring endless theories based on unprovable or easily refuted axioms.

Fine with me, but don't think you've got a handle on anything, or what you're saying will convince a skeptic. It's too weak in axioms, and the logic doesn't follow.

Causation is not coincidence.

I know very little about GPI systems, which are relatively new .

If anybody has read up on them, please post some good links -you can fiddle way a lot of time googleing stuff.

Thanks in advance!

OFM

These guys have been around a while and have some intellectual horse power.

New Economics Foundation http://www.neweconomics.org/programmes/well-being

A recent book on income equality as an important societal marker has got a good reputation: http://www.amazon.com/Spirit-Level-Equality-Societies-Stronger/dp/160819...

Personally I was interested in mental health of traditional farming in Himalayan Buddhist villages (but never got to visit) and in their sensible agricultural arrangements in a constrained (dry) environment, and in their child-rearing and family adaptation over centuries. I have big book of studies but it is not electronically available. EDIT but is apparently available in UK Amazon http://www.amazon.co.uk/Himalayan-Buddhist-Villages-Environment-Resource...

I'm not particularly fond of GDP as a metric either. At the very least it should be measured per capita (GPPC), not in aggregate. And then perhaps it should be a median value, not an average.

Since happiness by most measures seems to correlate with GDPPC up to $15,000 or so maybe we should count the percentage of the population that has an income over $15,000/y.

If we want to look at alternatives that are free of some of the measurement problems associated with GDP and are not subjective we could take measurements like longevity and use them as a proxy for economic growth.

Also as was mentioned by others I also am troubled by graphs showing GDP vs energy. There are quite large variations between countries in GDP/energy used; right now I believe that if we capped energy consumption at current levels GDP growth would slow, but certainly would not stop. The growth of GDP is dependent on many factors, not just availability of cheap high quality energy.

The point I would make is that the economy isn't monolithic. Some parts are much more sensitive to oil prices than others. Take two examples - airlines as one industry that is highly sensitive to oil prices, and at the opposite extreme you might things like companies that sell things like bicycles or seeds for vegetable gardens (as just two examples).

In times of high oil prices, the industries that are highly sensitive are going to struggle to survive, and many companies in those industries will need to downsize or change their business practices to use less fuel. Industries that aren't sensitive at all may be able to continue on with far less of an impact. Each price shock is going to lead to yet another round of cuts in price-sensitive industries, and growth when it does come is more likely to come first in sectors of the economy that are far less price sensitive.

This is a valid point and can be carried one further; the global economy isn't monolithic. Certain national economies are going to be more sensitive to oil prices than others for a whole host of reasons. And I think we're seeing this play out in real time. The Asian economies with their higher utility of oil usage, their lower tax structure, their lower environmental standards, etc. are still growing strongly; 4, 6, 8% or more. The western economies with their much higher tax structures, heavy loading of social "safety nets", higher environmental standards, lower utility for oil usage, etc. are, for the most part, looking at 1% growth going forward (if that).

The sixty-four thousand dollar question is; with the economies within the global economy all being interconnected and interdependent, which link is going to fail, when will it fail, and then bring down the whole rotten structure.

Thank you for an informative article, I look forward to the paper.

The real oil price can be determined any number of ways: oil priced by GDP, oil priced by industrial output, oil priced against various currencies and oil priced by inflation/deflation. In any pricing regime the real price of oil is rising even as real output - what is the return on that oil's use - declines.

Even adding more cheap oil will return less as the necessary increase in infrastructure needed to consume the oil becomes a 'sink' for both energy and funds.

China as a 3d world producer with factories and little else WAS much more productive than a China with cars, freeways, luxury apartment complexes and 'high speed rail'. China becoming America or Japan is it becoming another dead economy walking.

Also, the economic consequence of energy return shortfall is deflation which becomes reinforcing. Oil prices decline, because customers are too poor to bid up them up. Any lower cost oil is held off the market as it becomes in turn too valuable to sell.

With more or less worldwide ZIRP (zero interest rate policy) credit has become irrelevant, we are in the middle of the energy deflation, not at its beginning.

Yes, Austerity is the order of the day.

Growth is no more and the next 20 years will be different from the previous period.

We are in a Global recession.

Why is it such a bleak picture....Because Growth is and has always been associated with OIL production/ consumption.

We have reached peak oil...Oil companies now search for oil with billion pound rigs in deeper and deeper ocean areas...desperate measures are now being taken...even going to war (Gulf wars).

OIL = GROWTH

We have lived through unprecedented growth over the past 100 years or so, but the party is over as we approach diminishing oil resources.

We have technology, science, education etc, but nothing I can see, can replace or be a substitute for oil...

You see, talk of an alternative for oil, inevitably means that rare earth materials, come into the equation and the operative word here is "rare"...

In the next 20 years, if growth world wide was to double, (i.e. 3.5% per annum growth), then the oil consumption/ production during the next 20 years would exceed all the oil production ever produced since day dot (simple arithmetic...work it out)....Obviously not sustainable.

So whatever political views one may hold, change is inevitable.

The fear is that during this transition, which is going to be extremely painful, the majority will have to sacrifice their standard of living, whilst a few will fight tooth and nail to maintain their standard of living....and who do you think the few, who are in power at the moment are.??....

But really, to see where all this is going to take us, we have only to watch the USA, because that is where all the consumption is at the most and that is where we shall see the effects of austerity first....Watch and learn from the events that is going to take place in the USA...

Unfortunately we have already witnessed an event in the Iraq war, instigated by the USA and backed by a UK Governmenmt....What next one may wonder.?

Take a moment to reflect on the choice of the word "insidious."

No doubt, one salient point of the article is that the true nature of these feedback loops are unidentifiable.

We continue to experience the "eroi" of the Deepater Horizon efforts-

Who can measure all the travel movements by all the BP representatives and the coastal population's effort to recover damages from BP?

How many miles of jet travel by attorneys? How many automobile travel miles by claimants. How many countless hours of future litigation, investigation, and or misappropriated regulation or other "business practices adjustments?"

Insidious indeed.

Hence, Orlov's Descent-Shock Model in which peak cheap energy triggers a positive dynamic between economic descent, and increasingly out of reach, expensive energy supply. Economic flows, which have roughly pushed forward for over 200 years-- (Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations published in the late 18thC comes around the time that British coal mining makes great advances in extraction)--now turn either negative or become more diffuse. And, finally, we know that transition itself and the cost of reordering the built environment needs oil as the construction fuel. So, the world even if it wanted to migrate more heavily towards natural gas still needs oil as the price of admission, to that transition. Finally, we are really good at doing nothing about problems, in groups. So, I am liking Orlov's Descent-Shock Model quite alot these days.

G

Figure 6 especially captures the point that the economy will continue to 'porpoise', albeit in a downward slope, unless it gets out of the narrow operating bandwidth mentioned in the leaked German military oil supply study.

Boy, the "Peak Era Model of Economic Growth" sure looks like and sounds a lot like Eric Janszen's "Peak Cheap Oil Cycle model" that was documented on the economic website iTulip in November of 2009.

It is part II of the write-up below and is behind subscription pay wall:

http://www.itulip.com/forums/showthread.php/12799-Peak-Cheap-Oil-Update-...

dbarderic,

I have never heard of that model, but would like to read it (for free...). Is there a link anywhere else?

Dave

Eric Janszen is making the rounds on all the right-wing radio shows with his new book.

He is the guy that predicted the next bubble is in alternative energy

http://www.harpers.org/archive/2008/02/0081908

The problem with this bubble is that we won't be able to distinguish it from any economic decline caused by oil depletion.

Unfortunately, no. I searched all over for a free version of the article or at least a copy of the visual chart that explains the theory. You need a subscription to view the entire behind pay wall article and economic theses. You can read part I of the article I linked to above. Part II is summarized and behind pay wall. Part two outlines EJ's thesis. One month is $30.

At one point I did have a subscription and have reviewed the thesis. The economic model is nearly the same as it outlines an economy that goes in a downward circular pattern of economic growth, spiking oil prices, economic decline, falling oil prices, then another attempt at economic growth again. Almost a ratchet type of effect rather than one continuous decent.

It is probably not worth it. Like I said elsewhere Janszen has been making the rounds on the radio circuit for his book on "The Postcatastrophe Economy" and the two times I have heard him, not a single word about peak oil or the effects of oil depletion. He is a pundit and probably not too deep.

Do you really believe oil sands cost $90 per barrel to produce?!

For Q1 2010 Syncrude Canada Ltd. (Syncrude) reported operating costs of $41.81 per barrel of SCO, and production costs of $25.37 per barrel of bitumen. Canadian Natural Resources Limited (CNRL) has reported a similar $43.12 per barrel of SCO. Meanwhile, Cenovus Energy Inc. (Cenovus) and ConocoPhillips Canada (ConocoPhillips) have reported in-situ operating costs of $16.41 per barrel of bitumen produced at Christina Lake and $11.11 per barrel of bitumen produced at Foster Creek.

http://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=5aa1f6d6-9c0b-4cd8-baae-ab...

When conventional oil starts to deplete unconventional will be developed as there are no ready substitutes for petroleum.

Majorian,

Those are not my numbers - in fact they are from CERA.

CERA. 2008. Ratcheting Down: Oil and the Globabl Credit Crisis. Cambridge Energy Research Associates.

Please provide a link.

It's not that I don't trust you but..I don't really trust you.

;^)

My link to syncrude is,

http://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=5aa1f6d6-9c0b-4cd8-baae-ab...

I gave you the link. the report exists - i just can't access the full thing and can't provide the figure here.

http://www.cera.com/aspx/cda/client/report/reportpreview.aspx?CID=9812&KID=

-dave

OIL could be the next international monetary exchange standard.

Because oil will be a diminishing resource, the world demand for oil will increase its value.

Prior to the 70s, there was the gold standard…the value of the dollar was guaranteed by the gold in Fort Knox.

We have got away from the gold standard. After all what is gold useful for…(electrical contacts)….and so the Dollar became the international currency standard.

However Dollars are easily printed……and the printing machines have been very busy recently….

The world needs oil, so it will become the international standard of currency..

1 barrel of oil = how many Dollars.?

1 barrel of oil = how many Euros.?

1 barrel of oil = how many Pounds .?

1 barrel of oil = how many Yen.?

1 barrel of oil = how many Yuan.? Etc. etc.

As Peak Oil is upon us, the value of a barrel of oil will escalate. (After all the international price of Gold has escalated recently)….This Gold bubble will burst soon when it is realised that OIL and not GOLD is the real world…Just like the black tulip.

So the three most important things about international currencies, will be..

OIL + OIL + OIL.

The grab for oil, will be frightening and possibly there will be wars over it. (Oh just realised, there already has been wars over oil recently …Kuwait and Iraq).

The weakest countries (i.e those countries that have no access to oil) , will be the ones to suffer first…Their currency will not buy a pint of oil.

It will not matter how many plastic cheap toys or cheap designer dresses or clever electronic goods that that country manages to produce in it’s sweat shops…It’s currency will depend on it’s access to oil.

So take Spain for example…has it got access to oil…or Italy….or Ireland??...Will the Euro maintain it’s value in the world, if some or most of it’s countries have no oil and don’t or can’t produce anything of value internationally.??...Where will it get it’s oil from, with diminishing currency value against a barrel of oil….

This recent international financial crisis and an international chase to austerity is a sign of things to come, as it is realised that the value of a currency will all depend on the price of a barrel of oil.

EVERYTHING WILL DEPEND ON OIL.

Actually I think that food (and probably water) may prove to be the ultimate thing humanity needs but we are a way off this yet -certainly prices will rise considerably till we get there.

Gold will do well too untill the whole thing collapses.

Nick.

'.

EVERYTHING WILL DEPEND ON OIL.

I beg to differ. The major oil exporters are generally unable to feed their own populations. Saudi Arabia, for example, imports 79% of its cereal consumption.

Countries which can produce a food surplus for export, even with high prices for oil, will be in relatively good shape. I doubt if there are many such countries.

Countries which cannot feed themselves even with low oil prices, and buy both oil and food by selling manufactured goods, will have a tough time.

Countries which rely on food aid today . . . well they're the ones which will feel the truth of Malthus' predictions first and most violently.

And don't forget water.

Here's a graph smoothed for the fluctuating price of the $;

-as its a ratio no amount of QE would help out here.

Things to note:

1. During the Clinton Years / 90s oil was cheap and "Peak Cheapness" was reached in 98/99. This was also around the time Gold bottomed.

2. Energy/oil has got progressively more expensive in the last decade, culminating in a 'head shock' oscillation in 2007/8 about the time of the credit crunch/Lehman/stock panic.

I explain the increase in (2) by suggesting Industrialising Nations where/are mopping up spare supply at an ever increasing rate (read China/BRIC) and that the price shock ($147 oil) was caused by speculators seeking ever bigger returns once mortgage debt had run its course and jumping on the remaining thing that was giving returns into 2008: a multi-year commodity 'bandwagon' that eventually tipped the global economy 'over the edge' as the ratio reached down to 0.5. I don't have data going back much further than this but it would be interesting to see previous data and if/when it has ever dropped below 1.

Going forward I would suggest energy continues its upward price tragectory (down-slope in this graph) untill we are at somewhere near 0.5 at which point we endure another crash moment. This can happen either by debasing the Dollar from here by ~50%, increasing the oil price by 100% or some combination of the two...

Regards, Nick.

""Peak Cheapness" was reached in 98/99"

Some of us think that this was because it was the point of peak available energy--the moment when the maximum amount of net oil energy was being extracted. After that, falling EROEI caught up with still-rising-but-not-fast-enough total oil produced. By these calculations, the net energy extractable from remaining oil is, at this point, quite small indeed--maybe 10% of the total available when the oil age began.

interesting paper! I wish I could be there to hear it in person, but I can't.

:-(

Here's another angle I don't think you considered.

Demand destruction making room for growth. As long as the demand reduces faster than the decline in production, your economy can (technically) grow.

Random scenario: massive rationing, oil goes to specific necessary industries. The poor get squeeeeezed even more, lots of suffering, but the economy "grows", even on declining inputs.

Brutal, yeah, but I'm just looking at what you wrote and considering "ways around it".

have a good time in DC. I lived there for 9 long miserable years. Check out the Ethiopian food in my old 'hood, Adams Morgan - brilliant stuff.

David,

Very nice. I posted a response yesterday to Hannes work that bears on this as well. I think its really important to realize that our current problem is not only the dynamic you described above(the extremely convex shape of the marginal supply cost curve as you move from 80 million barrels to 90 million, just to pick numbers), but also that we lack a broadly helf belief in the future scarcity of oil. This means that our financial system cannot effectively put to use the increased savings that come from higher oil prices (because in my model at the current time, the change in the terms of trade is greater than the change in amount of resources the oil patch sucks from the rest of the economy).

I really like your schematic, but it another one needs to be added.

Increase Demand> higher oil prices > petro-windfall > attempted reinvestment of said windfall > failure of reinvestment to ameliorate oil problem > consumer exhaustion/bankruptcy > destruction of credit enabled economic activity > lower demand > building inventories >lower spot oil prices.

Its important to quantify whether the increase in oil prices is mechanically more a sucking of resources from all of society towards oil production, or a change in the terms of trade between oil production and consumption. I did the work a while ago in another context and believe strongly that at the current point of time it is the latter. I do believe that we are relentlessly moving towards it being more of the former, which by the way is the neo-classical definition of a resource constraint (where the long term average costs curves cease to decline).

Why does this matter? I think it matters because it suggests that the fundamental problem we face right now is not one of physical system determinism, but rather of coordination. The world cannot agree on a plausible use of its current surpluses (petro states, capital exporters, etc...) to fund investment that would ameliorate our oil dependence. Economic coordination is very important, and conventions that allow us all to make decisions in the present based on shared expectations of the future are the most obvious example of this need. Think of how crazy it is that at the height of the oil price spike (which was an increase in world savings, even though a decrease in U.S. domestic savings precisely for the reasons laid out above) the world decided that the best course of action was for the surplus to be recycled back into the U.S. in the form of consumption and construction. Ha.

There is an assumption that economic growth is a good goal for a society to have. The economic goals ought to be to minimize poverty on one end and concentration of wealth on the other end. Economic growth has not been shown to do either job at all. For instance the GDP is higher than it was 10 years ago and the number of poor in America is at an all time high and as a percentage of the population the highest in over 40 years. Economic growth ought to be seen as the result of reducing poverty and not the method.

I think the basis of that assumption is that, starting in the 19th century, growth was good for all of the segments of society. The working classes of the entire western world became much richer, while the "titans of industry" gathered up fabulous wealth. Even as late as the post WW2 era economic growth did mean increasing wealth for the working classes of the industrialized societies. While that model has become less effective,or even counterproductive in the US, no one seems to know another way to increase the quality of life of the average citizen. Today it seems that the European style mixed economy is the best solution but who would predict that it can last much longer with ageing populations and troublesome immigration? It, too, depends on growth.

Great post David, particularly insidious feedbacks. I've been harping on price for a long time now, saying the actual peak date for oil is secondary to the economic effects of relatively high priced oil.

I remember well the recession of 74 via high priced oil, and noticed at the time the economy did not begin to rebound until the price of oil dropped back down.

fact is, we're stuck in a recession that will only get worse over time.

David,

One of the arguments made in response to these discussions is that of correlation vs. causality. You mention in one of your responses that there are papers that clearly indicate a causality between energy and income (represented, I assume, by GDP). I think that one of the problems is that this discussion talks about oil, not energy.

I, personally, believe that the bottom line would be the same, but the argument might be more effective if presented in total energy terms (and total energy per capital terms). As I said, to me the link between energy and growth is self-evident, growth requires energy and cannot proceed without it. Any significant long-term growth requires energy supply growth. From a presentation point of view, perhaps you might want to make the case that:

a) energy is required for growth

b) increasing growth requires increasing available energy at economically affordable prices

and then ask and answer the questions...

1) can we continue to increase available energy given peak fossil fuels?

2) if (1) is technically/physically possible, can we do it at a price point that does not cause economic contraction?

Presenting the argument on an energy basis, rather than an oil basis, I think would address some of the criticisms. If you are firmly of the belief that oil supply, by itself, is sufficient to determine energy growth and therefore economic growth, I think it would be helpful to more definitively make that connection (e.g., perhaps liquid fuel prices and availability are sufficient to cause economic havoc regardless of the availability and price of electricity, etc.). Perhaps your paper already explores all these issues.

I look forward to seeing the finished paper.

Two other quick notes:

- In the text and one chart you use $58 as the average for price during expansions. In Figure 4, the line appears to be drawn at $68, not $58.

- It seems unlikely to me that the oscillation would occur around a flat trend. The nature of the volatility would be a positive feedback, in terms of reducing investment in future supply, resulting in an increasing decline rate over time. At least, it seems like that's what would happen.

Brian

Brian, thanks for the comments.

I focus on oil because it has the largest impact on economies, but your comments about the whole energy system are correct. I definitely drew the wrong line on that figure - thanks for noticing. I wonder if the peer-reviewers will catch it!

-Dave

Economic growth has been declining for a century in the U.S. We already replaced all human and animal physical with machines and have efficient, automated processes for manufacturing and computers for back office operations.

In growing food, oil related cost is about equal to other cost at $50/bbl. At $100/bbl oil is almost three quarters of the cost of producing food. Then there is transportation and distribution of food. As people spend more on food and gasoline there will be economic contraction, as we are now experiencing. We cannot overcome oil prices increasing several percent per year with productivity growth that probably is really something like 0.5%. That explains the economic crisis of recent. There is no breakthrough on the horizon that will restore economic growth. Energy substitution would at best only maintain the economy at near zero growth. A breakthrough that actually lowered energy cost would not create a boom unless energy cost approached zero. For comparison, electricity costs fell around 90% since 1900. The big slowdown in growth occurred soon after electricty prices leveled off around 1970.

Unemployment will stairstep higher with ecah new downturn. Government insolvencies will result, with Japan being the huge approaching shock to the world economy.

I'm glad somebody finally said it.

It's not just about the oil.

It's about blind faith in the mantra that:

Greed is Good,

Efficiency is Good,

Low labor costs are Good,

Offshoring is Good

From the usual perspective, replacing ourselves with machines is a great tragedy. But look at it from another point of view:

Manual labor can be enjoyable occasionally, but doing it as a career sucks. So does office drudgery. If our society eventually turns into one in which all the repetitive jobs are done by machine, and humans only work in entertainment, education, volunteer public service and medical care, is that a nightmare scenario?

Or is it the closest we'll ever get to utopia? A society in which everyone works to have fun, learn things, and help their neighbors sounds pretty good to me!

Of course, it takes energy to keep the machines running, but a machine-industrial future might well be more energy efficient than one dominated by human labor. Humans, after all, run only on one kind of fuel, a fuel which is energy-inefficient to produce and and which humans don't use efficiently either.

Anyway, I don't want to come across as a pollyanna here, but I do want to question the basic assumption that a future full of machines is necessarily a dystopia. Let's consider not just The Matrix as a possible future, but also the Culture novels of Iain M. Banks.

That's not obvious to me. Simplistically, in a world where everything you need to survive is free, all men are both kings and paupers.

But more realistically, why would mechanization target the middle class in particular? To crudely assign roles to the classes in our society, the rich provide capital, the poor provide menial labor, and the middle class provides technical expertise. In a world where material goods are cheaply made by robots and factories can be retooled by software, it's possible capital will be no obstacle, menial labor will not be needed ... but technical expertise will still be valuable.

Not saying that's certain, but your middle class doom scenario isn't well justified.

There will be no unaffected social class. There is no real return on most capital. Interest rates are negative, even before taxes. The only reason the stock market is doing as well as it is is because of negative interest rates. When it is apparent that we are in irreversible long term contraction, equities and small businesses will devalue. Those who own natural resources and land will be the winners.

Labor and capital are in oversupply. As for reprogramming factories and using robots, the question is to produce what? There has been a surplus of productive capacity since 1925. The work week has declined from 70 hours to 33 in the last 150 years. In theory we should be wealthier if we worked more hours, but everything is in oversupply, except oil, copper, platinum, potash, metallurgical coal, etc. and soon grains.

The fundamental beliefs of Western society are based on growth. Some of these are saving and investing for retirement or relying on pensions and social security. Also government borrowing. For government and other debt to be repaid, the stock market to grow, and the financial industry to exist, there must be either economic growth or inflation.

The limits of technology to replace labor have been reached. For example there are the Japanese robot junkyards. It many cases it is cheaper to use offshored labor at a few dollars per work day than to employ robots that are enormously expensive to build and maintain. This was not the result of higher priced oil. If faced with constant resource prices we may have been able to maintain an equillibrium but would still have had an economic crisis. Declining resources mean that we are approaching the end of the industrial and information revolutions and will be headed into an entierly new age.

“He that will not apply new remedies must expect new evils, for time is the greatest innovator.”

—Francis Bacon, Essays

I had a bit of an epiphany reading these texts along with the texts of "The Fake Fire Brigade Revisited #4 - Delivering Stable Electricity":

In the United States, decades of time have passed without the fully exploitative development of nuclear energy. This is an artificial situation. It has led to an under-use of nuclear energy that is, perhaps, comparably, as deep as the overuse of oil. The guttering oscillation of the economy in plateau described above is also known as a relaxation oscillator. It is like the "motor-boating" of an old-school transistor radio trying to run on dead batteries: the radio cuts-out, the electrochemistry of the batteries recovers a bit, the radio tries to function, the batteries fade immediately back down, the radio cuts-out... (at about seven cycles per second in this example). So... perhaps the novel development, the salvation of this terrible moment, will be nuclear power: We know how to do it. Is is better than massive disruption, upheaval, and decay. If it only lasts a while and makes a mess... so what? All technology is stop-gap: it gets you from here to there, like whale-oil. The energy will buoy-up the leaders in their insane and foolish pursuits. Continuity will obtain. Maybe someone will remember that we need new planets to plunder... There are many new reactor designs. Here is a forgotten blast from the past:

http://nucleargreen.blogspot.com/2007/12/aqueous-homogeneous-reactor.html

http://www.orau.org/ptp/collection/reactors/cs137homogeneous.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aqueous_homogeneous_reactor

The use of oil as a feedstock is a separate problem:

http://www.energybulletin.net/stories/2010-09-17/fred-kirschenmann-speak...

"Fertilizers, pesticides, equipment manufacturing and operation, all rely upon cheap fossil fuels. When the cost of fossil fuels goes up, farming costs skyrocket. In Iowa, anhydrous ammonia went from $200 per ton to more than $1,000 per ton almost overnight when energy prices peaked in 2008.

'Course, ya might want some dirt with that:

http://www.dirtthemovie.org/

Maybe some water, too:

http://www.agmrc.org/renewable_energy/climate_change/climate_change__imp...

.

.

.

Pretty song:

http://vids.myspace.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=vids.individual&videoid=231...

Err, but that claim is not supported by our own data examples

If you look carefully, at

http://www.theoildrum.com/files/Figure2_a.png

there are a number of important details:

a) The fitted line does NOT pass thru 0,0; it shows around 3% growth is possible, with no Oil increase.

b) There are many data points showing an INCREASE in GDP, with a DECLINE in Oil

- quite clearly, it is NOT always required to have a "commensurate increase in oil supplies".

Other countries have done better, so the smarter question, is to ask how do you get more into that first quadrant ?

Cheap is widely variable, as so is growth.

Certainly, the long term (non) availability of affordable FF (finite fuels), is going to drive changes. In some sectors, this change will be larger than other, and just like any change, there will be winners and there will be losers.

Incomes that depend on the discretionary use of finite fuels, will be the most exposed.

We-the-people sure don't behave like we value human labor - our actions would indicate our deepest commitment is getting more for less.

Perhaps it is because we actually DON'T value it! "Hey, it isn't MY job to need other human beings, isn't that what the Economy is for?" "If there's unemployment, isn't it the fault of the government?"

Right, outsource responsibilty. People who pass the buck to their leaders get leaders who pass the buck.

Fractals. Run an equation again and again, and a pattern will emerge – something that looks like a fern leaf, say. Change the equation and you can get an entirely different pattern – a coastline, or a fungus colony. The patterns may have characteristics which appear to be “centralized” (like the apex of a pyramid), but in fact there is no centralized control in the entity which emerges. Decision-making – if you want to call it that – is diffuse. And this is relevant to our discussion here – the issue of where we choose to assign blame and responsibility in this thing we call civilization.

The equation we are running - hundreds of billions of times - is "get more for less". In the life-and-death Darwinian economic struggle that emerges, the survivors MUST behave like BP and Wal-Mart, Exxon and Georgia Pacific – i.e. like sociopaths. Moreover, given this equation it is INEVITABLE that Wall Street will buy Washington. Nothing short of a revolution in the equation – i.e. the spending habits of hundreds of millions of people – will change matters.

For sure Change will not begin at this place we call the top.

The fact that this is not obvious to everyone is proof of the insanity of our time.

Dave, I like your Figure 1. You need to learn to plot a second y axis - its easy, and to add the third key variable which is population and stick in a bit of forecasting. Energy = money. People = GDP. (with a few minor adjustments).

Those last two graphs seem to show a considerable rise in oil production in the last five years. That does not seem to be the case. Am I missing something?

Dave,

Whilst I agree with your basic trust of what you are saying, I would also say that Oil & Energy do not exist in isolation.

Oil & Energy per se, are part of an interlocking whole, in which humanity integrates Population issues, such as Aging, over-population & decline, other major factors include Debt, Climate Change & human interaction with ourselves.

The human condition itself is a source of major conflict, as some want to retain what they have, whilst others see what is available and seek it for themselves!

You talk of a flat trend, a steady state and possibly dare to say, declining trend.

I would observe that you have rightly pointed out regarding Oil & Energy and that the other major factors of Aging (Baby Boomer Bust), an actual declining population starting within 20-30 years, Global Debt oveflowing & Climate Change, are all conspiring to prevent the usual Economic remedies!

Given the broad thrust of all major influencing factors, I would suggest that there can be no flat trend and no steady state.

Global Economics is now set on that growth paradox, which leads to a highly volatile economy, which oscillates frequently between expansion and contraction, but now the new trend line is down and it is set to continuing reversing until probably the end of this century or longer.

As usual, there is a possible way out and that depends on whether a cheap and abundant replacement for Fossil Fuels is found, in terms of Power generation, Liquid Transport Fuels & the many others uses, as well as a quick agreement can be found thru the human condition, to implement that new Energy source, with a Manhattan project urgency, on a Global basis!

Very nicely put.

The impression we get from a lot of these reflections on these changing times is that we will see clearly perceptible ramp-ups in economic activity, then the balancing rise in energy cost then the consequent ramp down in economy again - in cycles taking perhaps years, possibly months.

I believe we see this occurring in much shorter time-frames - days and at the most weeks and sometimes hours. The variability in crude prices is matched very rapidly by economic performance.

The economy of my own small and remote country went through the 2008-2009 big dip with all the bells and whistles, and over quite long time-frames (months, at least) things trended to bad, then things seemed to ease back to better.

But now here in late 2010 the 'wobbles' between individual businesses and whole local economies appear to be bouncing around the present oil prices within a fairly tight range on a daily basis; but with a pretty steady trend away from Business as Usual towards The Other Place.

We don't see immediately-measurable or recordable changes in the local on-the-street indicators - Petrol prices wriggle up and down without apparent reason, stuff at the supermarket seems to cost more each time, but there is not enough to give individuals a "Wow! This is getting Bad!" experience. But I think there are enough people and businesses well engaged with the key global economic indicators to ensure that their business intuition is reflected in what happens on development sites, on the street and in the cash registers.

The sum of this sensitivity is that we will see a decline down the back of the Hubert Hill in the form of small local wriggles interspersed with frightening down-steps as we hit increasingly likely then frequent non-delivery of fuel boundaries. We've just had an economic hit in the form of a major earthquake hitting one of our major cities, and currently the biggest storm on Earth is beating up the country from one end to the other. So whammy upon whammy, and none of them helpful.

Our Government has absolutely no sensible response to this prevailing economic circumstance; except borrow in the expectation that we (aka: our children) will be paying back when things get better, or even any process to discern it. So we-the-people are left to make our own arrangements.

Not pretty!

Actually it probably IS possible to arrange it, but it probably won't happen.

The key is efficiency and pushing down oil usage via efficiency faster than you want the economy to grow. Every year. Year on year. That way you create headroom for new 'growth' by cutting the wastage.

As an example, if you mandated that the average mpg of new cars had to be 50mpg, and you actively ensured that the replacement rate ran at the rate that would replace the entire fleet in 20 years, then you would be able to cut oil usage fast enough to accommodate your desired growth.

In theory.

Of course you would have to do this on a global scale, and China and India wouldn't be allowed to going on digging a deeper hole. And oil peaking would add to the rate needed. And I'm sure Jevon would come out to spoil things unless you played hardball with usage as well (hello rationing). But on the positive side, the building of these new vehicles would be growth creating, CO2 targets would be easier to hit, and there are other efficiency levers that can be pulled to get the overall efficiency improvements.

Trick is to do it NOW (each year, not decade), do it hard, and not allow the high growth countries to run away with the proceeds.

All of which needs a political maturity, which ............... well I said I didn't think it would happen.

There is an Alternative Paradigm.

One result is likely to be increasing wealth coupled with reduced income, although reduced income is not certain (just probable).

The alternative ?

Reduce consumption and divert those resources into long lived energy energy producing and energy efficient investments.

Conserve faster than depletion and steadily shift over to sustainable, non-carbon energy sources (basically renewables + nuclear + HV DC transmission + pumped storage + anything new that develops).

Wealth is a "balance sheet", and not an "income statement". Wealth can increase if "we" save more and invest it wisely in productive assets, even if incomes drop for a couple of decades.

Best Hopes,

Alan

PS: Sorry to be late to post but the False Firemen article has taken too much of my time.

I think your conclusions are sound and useful, but the way you start into the subject troubles me. You may be inviting cheap shots from classical economics-oriented readers.

You are basing your argument on a correlation between US GDP and energy consumption; I suggest you go further and explain the basis of the correlation- e.g., energy is the capacity to perform work, and all but a miniscule portion of the physical work done in the human economy is done by energy from fossil fuels. You hint at this by easily equating high EROI energy with cheap energy- another key point that ought to be explained. Why does the dollar cost of a unit of enery correlate so well with its energy cost?

I think some discussion of these key points would put the paper on a firmer basis.

''''''''''''But if you believe as I do that the world is entering a unique period defined by flattening and then declining oil supplies, then for the first time in history we may be asked to grow the economy while simultaneously decreasing oil consumption, something that has yet to occur in the U.S. In this post I attempt to answer the following question: Is a return to long term economic growth possible?''''''''''

Ha ha.

Thats what I love about the Oil Drum and its bloggers... peer review?

Sounds like 'the backing of corporate fascism'' is the actual desire to have this so called 'information' stamped with some legit air.

Non market economics is not being discussed. People like Charles Hall work for large Corporate run 'Schools' that get their funding from special interest groups.

The Political Price System runs the 'growth' ideas... that worked for around 4500 years... as contract society... capitalism, communism, fascism .. whatever but now does not because Adam Smith economics ... a silly joke now,.. is trying to be reinforced in posts like this one. Unknowingly of course.. which is kind of sad, but so much for 'American intellectualism or even creative science presentation these days.

No viable information is even floated here of real energy economics biophysical economics.

Actual energy accounting ideas in a non market energy balance system such as proposed by the Technical Alliance long ago.

Did Charles Hall ever in his life float ideas like M. King Hubbert did??? about actual alternative things ... ways to operate society without destroying the resource base?

Growth... economic money growth.

People that post here thinking they have serious information to give are about 80 years behind the time https://docs.google.com/Doc?docid=dfx7rfr2_93dqt642&hl=en 1934 or 5 most of the issues here were figured out.

Now people like the people that wrote the nonsense about Keynes here fiddle away.

American intellectualism used to be pretty cool.

Welcome to Sarah Palinville.

Hello Suckers!