Tech Talk - Where to Expect More Oil to Come This Year

Posted by Heading Out on August 25, 2013 - 5:04am

The news that Saudi Arabia is planning to employ 200 drilling rigs next year (up from 20 back in 2005) suggests that there is a recognition that future reserves may not measure up to the planned volumes needed. Plans now include exploration of the shale deposits in the country, looking primarily for natural gas. There are estimates that this resource could run as high as 600 trillion cubic ft. Current plans are to drill seven exploratory wells in the Red Sea, off Tabuk.

This is across the country from the major oil fields currently in use, which lie more along the Persian Gulf coast, centered perhaps around Damman. It therefore suggests that they are looking for extensions of the Israeli and Egyptian fields into northern KSA. (Minister Al-Naimi said that they still “had to find them.”)

In discussing the venture Saudi Minister of Petroleum and Mineral Resources Ali Al-Naimi also noted that, choosing to look for – and presumably finding - natural gas, would take the pressure off the country to maintain its oil reserve.

Al-Naimi said that prospects for global production of shale gas and oil – including in China, Ukraine, Poland and Saudi Arabia – were so promising that the Kingdom might not need to continue with its decades-long policy of maintaining an oil-output cushion for use in global supply disruptions. “It is not a question whether Saudi Arabia has spare (oil) capacity. It is a question of whether we need to spend billions maintaining it at all,” Al-Naimi said.

Now over the years KSA has lowered the volume it has projected that it can produce from 12.5 mbd to 12 mbd, and this is, perhaps, an early indication that they intend (whether by policy or natural reserve availability) to lower that maximum further.

This has to be of at least a little concern, since the number of places with significant flexibility to increase production are getting closer to zero every year. The gains in global production that are foreseen by OPEC in the next year, for example come in dribs and drabs.

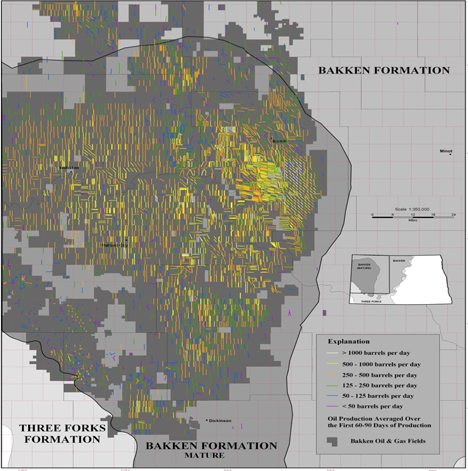

OPEC notes that in May the 8,915 producing wells in North Dakota collectively produced over 800 kbd. (The Department of Mineral Resources reports 821 kbd in June, over the 811 kbd in May with well numbers of 8,932 in May and 9,071 in June. Production per well is thus running an average of 90 barrels a day, with a well cost of $9 million.) There are 187 rigs plus/minus working and this is still enough to keep production rising at a rate of 1.3% per month. One of the maps I find interesting is this, from the Department.

It is this illustration of the relatively heavy drilling already in the “sweet spots” and the poorer performance in the less well- drilled regions that gives me concern for the longer term prospects for the formations. And as an aside note, that crude from Alaska is declining, July output was 498 kbd against the year-to-date average of 542 kbd. The EIA is noting that since there aren’t any major oil pipelines running into California from the East, that there is an increase in rail traffic to make up the difference. The EIA is suggesting that the traffic is already at a level of around 100 kbd.

And this in happening in the most promising region to increase production (though it includes Canada, for which OPEC projects a growth over the year of around 40 kbd, and is set against Mexican production, for which OPEC sees a decline of around 60 kbd).

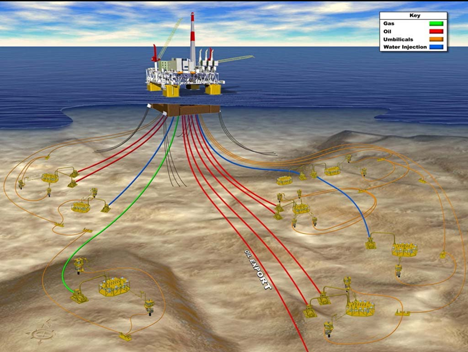

Malaysia is projected to increase production by 50 kbd, from the Gumusut field. This is a Deepwater project, and one can get some estimate of the shape of the field from the well pattern. The production gain is viewed by OPEC as likely being the highest in the region.

In Latin America Colombia is expected to increase production by 80 kbd, though the country is having some issues with pipe damage from terrorism. There have been more than 30 attacks this year. OPEC also looks for an increase in Brazilian production of 10 kbd over the year, this gain coming after some 14 months of decline, which drop will hopefully be recovered before the end of the year.

Oman will grow production by 20 kbd, but it is in Sudan and Southern Sudan that OPEC anticipates the greatest growth, of 90 kbd. However the two countries are not the best of friends, with oil from Southern Sudan having to ship by pipeline to Sudan, for shipment onwards. At present oil, at an average rate of 75 kbd is continuing to flow up the pipe, but Sudan continues to threaten to halt shipments, leading Southern Sudan, in turn, to plan to shut-in the wells. The OPEC projection seems to be best defined therefore as “iffy.”

OPEC expect Russia to increase production by 80 kbd in 2013, yet there is some caution in that estimate, with other numbers suggesting that Russia is reaching a modern peak in production. Kazakhstan is projected to increase production by 50 kbd (coming from the startup of Kashagan, now expected at the end of September). The 100 kbd production will more than offset declines in the rest of the country. And China may increase production over the year by 60 kbd.

I have listed the countries that OPEC anticipates will grow production by more than 10 kbd, and have not listed the many countries that will see production decline by more than that amount. It is remarkable that listing the increases in production outside of OPEC can be done with just a few paragraphs. And it is a little disturbing that the threats to pipeline security throw questions over the reliability of some of the numbers. Yet this only addresses the possible growth in production - declining producers would require a much longer list. Combined it becomes a little more difficult, as turmoil in MENA continues to grow, to remain optimistic over the OPEC projections.

On the decline side, Australian C&C saw a production loss of 48 kb/d from 414 kb/d in financial year 2011/12 to 366 kb/d in 2012/13. That is 11.5%

See table 1A in the June 2013 file

http://www.bree.gov.au/publications/aps/2013/index.html

We need everyone to believe that there is plenty of oil supply otherwise there might be a crises of confidence and through the world into and economic tailspin...and the people in power might lose their positions and more.

As annual Brent crude oil prices doubled from $25 in 2002 to $55 in 2005, Saudi net oil exports increased from 7.1 mbpd in 2002 to 9.1 mbpd in 2005 (million barrels per day, total petroleum liquids + other liquids, EIA).

The Saudi Oil Minister, in early 2004, explicitly stated that the large increase in Saudi net oil exports was an attempt to bring oil prices in line with the then stated goal of maintaining a $22 to $28 oil price band. In any case, at the 2002 to 2005 rate of increase in Saudi net oil exports, their net oil exports would have been over 16 mbpd in 2012, as annual Brent crude oil prices more than doubled again, from $55 in 2005 to $112 in 2012, with one year over year decline in oil prices, in 2009.

However, in contrast to the 2002 to 2005 Saudi response to the price doubling, the Saudis have shown seven straight years of annual net exports below the 2005 rate of 9.1 mbpd, with Saudi net oil exports ranging between 7.6 and 8.7 mbpd for 2006 to 2012 inclusive.

If the Saudis have virtually infinite oil reserves, and their public pronouncements continually suggest that they have the “capacity” to produce well in excess of 12 mbpd almost indefinitely, why are they allowing high oil prices to encourage alternative sources of oil production, e.g., the very expensive and very high decline rate shale plays in the US?

While it’s certainly at least possible that the Saudis abandoned their traditional swing producer role, and decided to encourage, starting in 2006, higher oil prices, and thus more competition, by cutting their net oil exports, it’s also at least possible, as Matt Simmons suggested in 2005, that Saudi oil fields are finite after all.

If the Saudis have virtually infinite oil reserves, and their public pronouncements continually suggest that they have the “capacity” to produce well in excess of 12 mbpd almost indefinitely, why are they allowing high oil prices to encourage alternative sources of oil production, e.g., the very expensive and very high decline rate shale plays in the US?

I suppose there's the possibility that they're playing a long game, and encouraging expensive plays like the Bakkan in order to exhaust them. Given the Saudis' rate of population growth and need for ever larger oil revenues, that might make some sense: let the US exhaust its shale resources at $100/bbl, so the Saudis are are the ones still in business at $200/bbl. The search for gas also makes some sense in that scenario, since large finds would allow them to substitute gas for oil for domestic consumption.

And not just increased US oil production but alternative transport fuel technology like natural gas and electric vehicles are both growing rapidly which completely removes those drivers from ever being Saudi customers again. In the past year, I've bought $9 of gasoline for a trip to the beach and a trip to neighboring city in my gas car that otherwise just sits & rots. I think I'll just call up charity to just haul it away soon and rely on ZIPcar for my long distance needs.

Reminds me of ...

DON'T PANIC!

Or with other words:

"Should there ever be not enough oil available on the market then it is really your own fault, because you failed to develop your giant amounts of shale oil. There's nothing we can do about that."

Looking at it from that angle I find it to be quite an amusing statement. Sooner or later he may come foreward and state that there is a shrinking market for Saudi oil due to the shale boom, so they have decided to reduce their output by 2-8% every year.

Why so little out of Brazil? For example in 2006 they announced the discovery of the huge Tupi (now Lula) deepwater field.

That oil is extraordinarily challenging to bring to the surface....

Start here and follow the links

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lula_oil_field

Yeah, that story was all over the headlines. What happened? I guess it is much harder, very expensive, and time-consuming to actually extract that resource. Brazil is still a net-importer I believe.

Considering the lack of any support facilities to keep the very large fleet of ultra-deepwater drill platforms on station--most of which didn't exist when the discovery was announced--I'm not the least surprised by the slowness of extraction. Then there is the very big issue of providing security for the field so it doesn't get pirated by the Outlaw El Norte.

And in 2012, Brazilian oil imports increased.

Petrobras, after the collapse of their stock price, cannot raise more equity capital.

However, Brazil seems content as long as they can produce 95+% of their oil consumption. Which is not an illogical long term policy.

BTW, in 2009, Brazilian electrical generation was 82.4% renewable (hydro plus a bit of bio-mass, # from memory). In 2001-2 they had a drought that caused an economic recession due to shortage of electricity.

Now they are building 7 GW of wind (which seasonally peaks when rainfall is lowest, and is stronger in states with weak hydro). The goal is to cut the fossil fuel generation by about half, and provide some cushion in case of another drought. Solar obviously has some unexploited potential in Brazil as well.

And they are building 10,000 km of new rail lines this decade.

Best Hopes for Brazil,

Alan

I have been following Bakken and thought that 2013 might be the peak year.

Oil rigs peaked @ 220 in mid-2012, but stabilized in the 180-189 range since December 2012. I expected a further fall to 150 range by today.

The collapse of the WTI-Brent spread raised wellhead prices by @ $15/barrel, And early Bakken wells were drilled too far apart. They have discovered that drilling between two good wells is profitable (although the well may produce a bit less than it's earlier neighbors).

I credit these two factors (plus lower drilling costs as supporting infrastructure matures for a stable drilling rig fleet) for keeping North Dakota drilling rig count stable.

December 2012 was the 60 year peak in oil per well (96 b/day) in North Dakota and that metric has been falling since. New wells today are not quite as productive as earlier new wells (Rune Likvern) and the number of Bakken stripper wells grows.

Absent a further increase in the price of oil, I expect the ND drilling rig count to fall in 2014, and North Dakota/Bakken oil production to peak in 2014 or 2015.

Not Much Hope for Further Increases in US oil production,

Alan

That is a pretty bold prediction. I doubt that will happen because if production starts to drop then oil prices will go up and the drilling will increase. The show must go on . . . for as long as they can keep it running.

I have a primitive question on the economics of these wells:

At ~100$/barrel, such a well would have to produce 90'000 barrels over its lifetime, i.e. be operating for 1000 days. Remembering the steep decline rates of these wells, they only seem to produce a lot in their first year or two. Of course the average of 90 barrels/day includes older wells. Nevertheless, can anyone quote a number on the necessary oil price for such wells to work economically?