Trade, Transportation and the Chinese Finger Trap

Posted by nate hagens on January 22, 2007 - 12:02pm

This post will examine the theory of international trade and the hierarchy of goods transport, production and consumption. It is quite possible that in the next decade,or two the increase in price (or the decreasing availability) of oil and financing, will offset the benefits of many types of trade.

The pursuit of economic efficiency, through increasingly diverse and extensive global trade has glossed over two important facts which this post will examine: 1)higher oil prices in long distance transport must at some point exceed (economically or otherwise) the benefits achieved from some trade and 2)a complex global trade system is gradually but pervasively decreasing the ability for localities, regions and nations to be self sufficient – so many of our supply chain inputs are imported that continued increase in oil price/affordability will resurrect import substitution policies, not only for less developed countries, but for the US and rich nations as well.

International Trade - A Chinese Finger Trap?

INTRODUCTION

The idea for this post originated on a recent errand to Fleet Farm to buy a replacement spark plug for my dads chain saw. I discovered there are not one or two kinds of spark plugs but hundreds, depending on the type of machine they go into. The plugs were made by a variety of companies, some domestic, some foreign but none from my state (currently Wisconsin). As I noticed this, I looked around the dozens of aisles and hundreds of shelves at the thousands of products and 'saw' for the first time how complex our import/export system has become. And the fact that my dad couldn't cut our firewood without that certain sparkplug reminded me of Liebigs law of the minimum, or in the vernacular - something is only as good as its weakest link. I couldnt help wondering how much oil was embodied in those spark plugs; their parts, their manufacturing, their delivery to central Wisconsin, etc. While my research didn't discover this answer, it did result in my viewing trade, transportation, and our societies consumption habits in a different light.

Much has been written on this site and elsewhere on the exact date or time range when we begin the second half of the age of oil. I will not address timing in this post other than to point out that the later it is, the more can be done to address the systemic risks suggested below. The human pendulum of complacency and panic is in full effect as oil breached $50 on the downside today. Those who read this piece and connect the dots should recognize that $50 oil is not a reflection of its abundance or scarcity but is rather an opportunity to effect change (because change is cheaper). There are after all, about Trade has been around almost as long as humankind. Historically it was largely a barter system, before currency was adopted as a medium of exchange. Modern international trade is based largely on Ricardian model of comparative advantage, one of the most eloquent but non-intuitive concepts in economics. Indeed, a story told amongst economists is that when an economics skeptic asked Paul Samuelson (a Nobel laureate in economics) to provide a single, meaningful and non-trivial result from the economics discipline, Samuelson quickly responded with, "comparative advantage."

ABSOLUTE AND COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE

The early logic that free trade could be advantageous for countries was based on the concept of absolute advantages in production. Adam Smith wrote in The Wealth of Nations:

"If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry, employed in a way in which we have some advantage. " (Book IV, Section ii, 12)

The idea here is simple and intuitive. If one country can produce some set of goods at lower cost than a foreign country, and if the foreign country can produce some other set of goods at a lower cost than can be done locally, then clearly it would be best to trade for the relatively cheaper goods of both countries (or regions). In this way both parties gain from trade.

If a person/region/country can make a product cheaper or more efficiently than someone else, they have an absolute advantage in this product. However, a country that can produce two things (or everything) better than another country can still benefit from trade. This is due to the brilliant (on an empty planet) theory of comparative advantage first articluated by David Ricardo. Here is an example.

The Magic of Comparative Advantage – A Hypothetical ExampleBoth Wisconsin and North Carolina have lots of trees, productive farmland, access to labor, and cows. (assume for this example their labor force and populations are equal) Both produce cheese and furniture. But Wisconsin (for various reasons) has an absolute advantage in the ability to produce both cheese and furniture. If they were to devote all their resources each laborer could produce 12 units of cheese or 4 units of furniture. In North Carolina, each unit of labor can produce 6 units of cheese or 3 units of furniture.

Wisconsin is 'better' at making both products, but applying the theory of comparative advantage, North Carolina is ‘less worse’ at producing furniture. This can be seen via the concept of opportunity cost. For every unit of furniture production, NC is giving up 2 units of cheese production (6/3). For every unit of furniture production in Wisconsin, they are giving up 3 units of cheese production (12/4). Therefore it is ‘more costly’ in terms of opportunity lost for Wisconsin to produce furniture than it is for North Carolina, in a world of frictionless trade.

Specifically, in a position of autarky (or closed economy), each state will devote half its resources to each production pursuit – Wisconsin will produce 6 units of cheese and 2 units of furniture. North Carolina will produce 3 units of cheese and 1.5 units of furniture. In our hypothetical world without trade then, a total of 9 units of cheese and 3.5 units of furniture are produced.

But then a trade agreement is signed. Because they have a comparative advantage in furniture, North Carolina devotes 100% of their resources towards producing 3 units of furniture. (and no cheese). Wisconsin produces 12 units of cheese (and no furniture). Now the ‘world’ has 12 units of cheese and 3 units of furniture. However, Wisconsin can easily shift 3 units of its cheese production to create one unit of furniture. The world now has 9 units of cheese and 4.5 units of furniture with no extra resources or labor.

Trade, via specialization, has magically created an extra piece of furniture, with still the same amount of cheese!

WHAT PRICE CHEESE?

A key question in this post: what happens when the cost of transportation of cheese and furniture between North Carolina and Wisconsin(via higher oil prices) exceeds the benefits from trade (an extra unit of furniture)?

I remember in graduate school thinking comparative advantage was pretty cool. But, like many things in neo-classical economics, comparative advantage relies on a battery of assumptions, many of which prove problematic in the real world. Josh Farley and Herman Daly succinctly describe some criticisms of the assumptions that underpin comparative advantage in their textbook "Ecological Economics"(1),

1. "No extra resources" simply means no additional labor or capital - there IS commensurate resource depletion and pollution accompanying the extra production.

2. The neglecting of transportation costs. Transportation is energy intensive, and currently energy is not only directly subsidized, but, in addition, many of its external costs are not internalized in its price. Consequently, international trade is indirectly subsidized by energy prices that are below the true cost of energy.

3. There are two important costs of specialization. First, all cheese makers (cheesesmiths?)in North Carolina must become furniture producers and vice versa for furniture makers in Wisconsin. Making such a shift is costly to all whose livelihood is changed. Also in the future the range of choice of occupation has been reduced from two to one - likely a welfare loss and assuredly an occupational risk.

Furthermore, after specialization, countries lose their freedom not to trade (the chinese finger trap). They have become vitally dependent on each other... Remember that the fundamental condition for trade to be mutually beneficial is that it be voluntary. The voluntariness of 'free trade' is compromised by the interdependence resulting from specialization. Interdependent countries are no longer free NOT to trade and it is precisely the freedom not to trade that was the original guarantee of mutual benefits of trade in the first place.(1)

CAPITAL MOBILITY

An often overlooked provision of Ricardian comparative advantage, but one of extreme relevance in today's world, is that of factor immobility (factors other than cheese and furniture). In reality, today's borders are porous to billions upon billions of dollars of capital movements moving to the areas of the world with the cheapest production. In effect, the rich countries have a comparative advantage in 'money' and are trading it for the labor and resources of other countries. A countries current account is the difference between the monetary value of exported and imported goods and services. When the imports are greater than the exports, the account is in deficit. If exports are greater, the current account is in surplus. So, comparative advantage, with the assumption of immobile factors relaxed has effectively resulted in the erasure of national boundaries for economic purposes. Some people call this globalization.

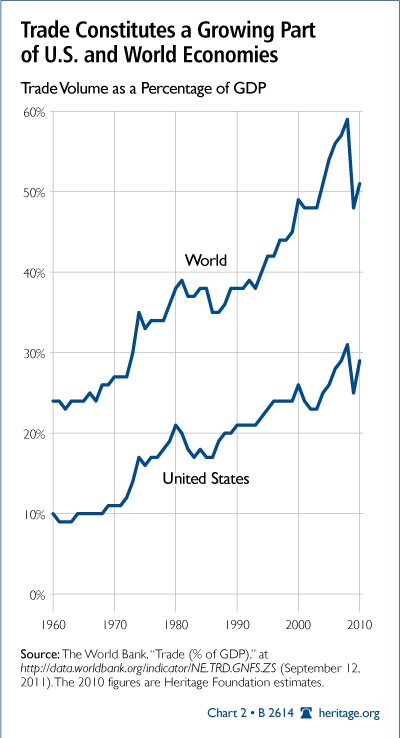

The following graph shows the increasing percentage that trade is out of total US and world GDP:

Source World Bank

Source World Bank

Below is a chart of US imports and exports and our trade balance:

US Imports and Exports - Click to Enlarge

As can be seen above, imports have been outpacing exports for some time and the pace has accelerated of late.

US Oil Imports by Country - Click to Enlarge.

Finally, it is of some concern that 'services' continue to increase as a % of our national ledger (implying that 'goods' are becoming less). We still do produce huge amounts of food for export, but that is increasingly being accompanied by movies, massages and things higher up the 'discretionary' hierarchy (more on that below). Here is a graph indicating the growth of services vs goods in our Gross Domestic Product and Employment. America seems to have a comparative advantage in 'services'. The counter-argument is that more services naturally arise as economies become less energy intensive - this view ignores energy as a unique input and therefore all countries can't become less energy intensive over time under a growth regime.

US Goods and Services- Click to Enlarge.

THE GRAVITY MODEL OF TRADE

The Ricardian model is not the only economic model dealing with trade. The

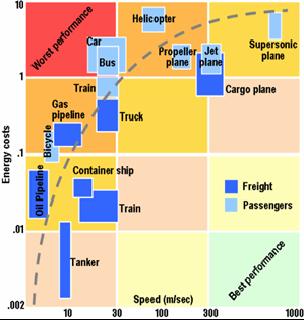

Here is another graphical illustration which incorporates speed (which increases energy return on time) and energy intensity:

Source: Jean-Paul Rodrigue Hofstra University

A recent article in the Economist points out that comparative advantage also works at our most basic level of trade (male/female) and was of historical significance:

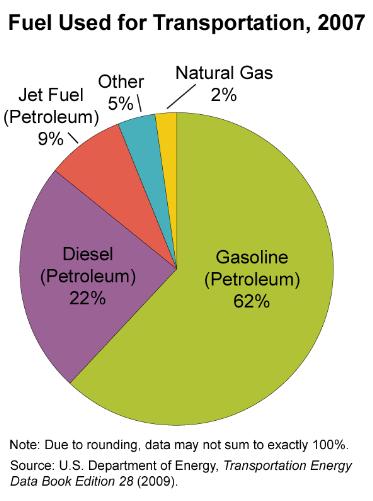

In the 1960s transportation accounted for about 23% of all energy expended in the USA- now the figure is approaching 28%. The yellow line (almost on top of the pink line) shows of the transportation, 99% of it is oil (there is some electrical, natural gas and coal usage)(3). We are really dependent on oil!

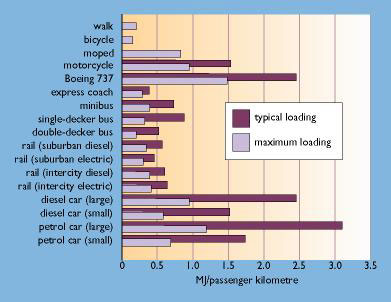

The following two graphs show the energy efficiencies of various modes of transportation first for people and then for goods. This first graph is from Richard Heinberg's book "The Oil Depletion Protocol" and is based on data from Britain (which Richard tells me is fairly universal):

As can be seen, the bicycle is the most energy efficient mode of transportation - even better than walking. The other insight from the graph is we gain quite a bit of efficiency from packing a lot in one vehicle. (This is a concept used often in China)

As far as transporting goods, there is a large disparity in energy efficiency per ton mile for different transport methods:

The above graph is somewhat dated (1991), Though there have been efficiency improvements across the board, the general model of water/rail/truck/air in order of efficiency seems to still be intuitively correct, though some argue that rail is more efficient than water. It is actually quite a complicated issue as it depends what one is transporting and the sequence of steps. Alan Drake recently did a study showing rail transport to be 8.3 times as efficient as trucking.

One can visualize the energy efficiency/footprint of various transportation modes as something like this pyramid:

As transportation costs increase, communities and regions that are able to effect movement downwards on the pyramid towards its base will have comparative advantages, due to savings on energy costs, and availability of products.

Let's now shift gears just a bit. Psychologist Abraham Maslow theorized that humans meet basic needs in a hierarchical fashion. Once basic needs are met, we seek to satisfy higher needs such as self actualization and fulfillment. In the current era of cheap oil, at least for western society, a very small % of energy is spent on basic needs in proportion to the energy intensive 'desires' that drive western society:

This concept can be expanded upon. We sometimes take for granted the things that we really need, and make us happy - I am 90% as happy eating fried fish from a local lake as I am driving to Chicago to my favorite sushi restaurant (well at least 80%). Higher personal consumption efficiencies in an energy challenged world are lower on the pyramid.

We finally come full circle to the spark plug question. There is a great movement (at least in the peak oil circles, not yet in the peak credit circles) towards relocalization. But 'local' labels in many cases are misleading due to the insidious reliance on foreign parts at different moments in the supply chain.

One of my best and oldest friends is an entrepreneur from China. He owns a business in Connecticut that seeks out American companies that need nails, screws, and small metal parts at their factories - he then signs contracts for 5 million screws at 2.5 cents each - screws that in the US would cost 6 or 7 cents due to higher labor etc. He pockets half the difference. The point being that our basic goods might ostensibly be made here, but their component parts may not.

I have not seen a way to measure this so have come up with my own, "the Embedded Transportation Chain". First Order Origin represents where you buy something (in your town would be 100% local). Second Order Origin represents where the components and parts came from on the product you bought. And Third Order Origin represents where the raw materials came from for the parts to make the Second Order Origin parts. To determine how 'local' (in the sustainability and security sense) a product is, one would multiply Level 1 * Level 2 * Level 3. Of course, there is very little that is truly local, as a world of increasing international trade has increased 'Third Order Origin' percentages dramatically. (I don’t have accessible data on this-the amount of work would be closer to an academic paper – here I just wanted to lay out the idea). True to the field of economics, I have made these terms up. However, also consistent with economics, one can grasp the common sense implications. When looked at in this 3-tiered light, the phrase “Made in America”, takes on different meaning.

I currently reside in Wisconsin. To eat local is cheese curds, fried fish and venison. All these things can be bought (or harvested) locally. But the cheese company gets milk transported from around the state, uses packaging made overseas from natural gas. Its employees drive to work using cars made in Japan and oil from Nigeria and eat food imported from New Zealand. Although the dairy farmers themselves use largely local inputs for feed and bedding, their milk buckets are made from steel processed in China, and the wood for the barn comes from a mill in Canada. It is not easy to decipher the ‘localness’ of a product, unless one walks out and picks a wild mushroom. Use your imagination however to consider WHAT IF oil doubles triples or more in price, what sort of domino effects might occur in the production supply lines. It is hard to predict what "Liebigs product of the month" might disappear from the store shelves - Charmin bath tissue one week and Stihl chain saw blades the next.

A quick example is footwear. 98% of all shoes in the United States are made somewhere else, many in China.

Increases in efficiency of goods production in a global context are considered a good thing, as they raise respective countries GDP, and allocate resources wherefore the total pie gets bigger. Once on this track however, participants continue to strive for more and more efficiency, more trade advantage and cheaper production. If taken to its natural extreme, every place on earth will specialize to the maximum profit of corporations. Implicit in this path is the forgoing of expertise and local resources that are lower down the pyramid of human necessities. If transport costs are 20% of a products value and oil doubles or triples, they become upwards of 50% of a products cost. Certain products then become uneconomic to ship. Some of those products are components of larger products which do not have local substitutes.

High quality and abundant oil has obfuscated the difference between wants and needs. At a Walmart or a Safeway, young people today see quilted bathroom tissue, pork chops, colorful shoes, dental floss, and avocados as a natural smorgasbord, without internalizing the complex energy/trade chain that put them there. This plethora of choices that globalization offers us could just not be possible in local or regionally based economies. In some senses, to revert the global network of specialization back towards less complex, more regional networks is kind of a chicken-or-the-egg dilemma. Unless we change the consumption drivers, there will be little incentive for the manufacturers of nascar lunch boxes to move downwards the production/transport and global/local pyramids.

When (and in my opinion its only a matter of when) oil becomes less available/affordable, centralized forms of energy command will not be efficient because different regional blocks and localities possess their own comparative energy and resource advantages and disadvantages. National umbrella energy policies treat all states the same. Corn ethanol roll out is a prime example - what might be great for communities in Iowa and Minnesota has different math for California and Vermont. We know that distance impacts energy efficiency and costs. We also know that different states (and countries) have different indigenous energy resources (Quebec has hydro – Arizona has sun, Montana has wind and coal, etc). It is likely there will be decentralization of energy production as regions move towards building blocks of basic needs in safer spatial scales. The magic of comparative advantage can still work in the second half of oil. But it ultimately will differentiate between basic needs and unnecessary desires - and take advantage of water and railway access.

1. We need oil for more than just driving. It is embedded in almost everything. Unless you're Amish, Aleutian, or have alot of friends, oil is life in the USA (at least currently).

2. Higher oil prices combined with lower (or no) credit availability will eventually make certain types of modern trade prohibitive. As such there is shortfall risk in modern supply chains that is not in current economic forecasts.

3. Those nations, regions, communities and families that produce lower on the left graph and consume lower on the right graph will have an advantage when transportation costs increase. Those communities using predominantly rail and water transport will have advantages over those more dependent on truck and air, everything else being equal.

4. As is occurring in some South American nations currently (Peru and Venezuela come to mind), a return to the import substitution model away from the so-called Washington consensus seems inevitable. However, remember the supply/demand wedges in the Hirsch/Bezdek report showing how rapidly production shortfalls could occur. Local, regional and national action needs to be taken soon because of the required long lead times.

5. In rich nations, in addition to conserving, it will be advantageous to begin to be happier with 'less' because the delta of 'desires' may change slower than that of 'things' available in the future, relative to other countries (e.g. Europe and Africa) that exhibit lower energy footprints. In other words, though the USA can easily get by with half as much energy-intensive stuff and conveniences, an abrupt change to this level will be much more mentally painful than a gradual one.

In conclusion, as a thought experiment, the next time you go to your nearest box store, look at the gazillion products on display. Try to imagine where they come from, where their parts come from, and how that supply chain might change when new oil production fails to match decline rates of older wells. While you are there, you might notice how many of the myriad products improve yours or your friends lives, and how many do not. This 'demand' side view of Peak Oil will be the subject of my next post.

Next post (if I successfully defer my addictions): "Evolution, Discount Rates and Addiction"

Nathan John Hagens

Resources cited:

(1) Ecological Economics - Principles and Applications, Herman Daly and Joshua Farley (in my opinion, a textbook that should be used in every college in America)

(2) "Gravity for Beginners" Keith Head. http://pacific.commerce.ubc.ca/keith/gravity.pdf (.pdf warning)

(3) National Transportation Statistics 2006(pdf warning), US Department of Transportation

Gravity Model of Trade -Commodity Flow Correlation with Distance (2)- Click to Enlarge. Energy costs vs speed

Energy costs vs speed

A PALEO-ECONOMIC PALATE CLEANSING SIDEBAR BEFORE WE MOVE TO TRANSPORTATION

In existing pre-agricultural societies there is, famously, a division of food-acquiring labour between men, who hunt, and women, who gather. And in a paper just published in Current Anthropology, Steven Kuhn and Mary Stiner of the University of Arizona propose that this division of labour happened early in the species' history, and that it is what enabled modern humans to expand their population at the expense of Neanderthals.

With the peak of conventional oil likely being in 2005, and the long decline in societal benefits from oil on the near horizon, perhaps I should brush up on my woodchopping and carcass dragging skills...;-)

TRANSPORTATION

Transportation as % of total energy use- Click to Enlarge

MegaJoules per passenger- Click to Enlarge

Energy Intensity per ton mile by freight mode. Source - EIA Click to Enlarge

The Transportation Pyramid. Click to Enlarge

ENERGY USE AND HUMAN WANTS AND NEEDS

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs------------------Nate's Intuitive but Made Up Hierarchy of Energy Use. Click to Enlarge

The Consumption Pyramid - Click to Enlarge

The Transportation Origin Chain- Click to Enlarge

CONCLUSIONS

THE BOTTOM LINE

theoildrum.com

email thelastsasquatch@yahoo.com

Consider this a reminder to positively rate this articles (using the icons under the tags in the story title) at reddit (note the new reddit counters! just click on them and hit the up arrow to help out), digg, and del.icio.us if you are so inclined. (email me at the eds box if you have questions about this).

Also, don't forget to submit this to your favorite link farms, such as metafilter, stumbleupon, slashdot, fark, boingboing, furl, or any of the others.

I can assure you that the authors appreciate your efforts to get them more readers.

I have read, it seems reasonable, that the majority of Americans live off the discretionary income of other Americans. Author Thom Hartmann addressed this in his book, "The last hours of ancient sunlight."

Hartmann described a software company that he used to consult for years ago. First visit: two or three people. Second visit: several more people, after another round of financing, bigger offices. Third visit: dozens of people, after another round of financing, very nice offices. Fourth visit: empty offices, they ran out of money, without ever delivering a product.

The point is that the majority of our economy is largely an illusion, albeit an illusion that consumes vast quantities of energy. Instead of gong to Vegas, you could just mail them a check for $5,000, and it would have the same economic impact.

We are facing a relentless transformation of the US economy--from one focused on providing "wants" to one focused on providing "needs."

Basically my ELP recommendations can be reduced to: Cut thy spending and get thee to the non-discretionary side of the economy.

As I have said about a 1,000 times, if I am wrong, so what?

You will have a lower stress way of life, less debt, and more money in the bank.

This is something that a lot of peak oilers don't understand. We are not going to create an economy based on doing each other's laundry. One, there's that constant growth thing. And two, when the going gets tough, people will do their own damn laundry.

When the going gets tougher, we'll wear dirty clothes.

No, when the going gets tough, most people will be unkempt, poor and surly, doing the laundry and servicing the whims and base needs of the few remaining people with power and money.

We will not be doing "each other's laundry" in some communitarian ideal. We will be doing Their laundry, their nails, their cabinets, their hair, their wigs, their blowjobs and their back-breaking agricultural labor.

GDP is quite interesting when you start digging a few levels deep. 72% of the US's GDP is services. We hear that our economic expansion is due to increases in productivity. How do you measure increases in productivity of services, such as a bank?

The Dept of Commerce measures, for example, a bank's economic contribution to GDP by by "net interest margin" difference between assets (loans mainly) and liabilities (deposits mainly). However, productivity of a bank is measured by the number of "transactions" -- using the ATM is considered a transaction as also when you go to the bank teller in person to get cash. Use of the internet to check balances I believe is also counted as a transaction.

Is it no wonder then that the US's productivity is increasing at a high rate, when the overwhelming majority of the economy is services and the Internet and technology allows for rapid transactions -- ie productivity.

It is also theoretically difficult to justify productivity -- which is defined as output per worker/hours worked for a bank when the GDP impact is net interest margin and productivity is "transactions" -- the two measures do not match -- more transactions does not mean higher net interest margin.

The Dept of Commerce admits that a "stronger theoretical basis" for measuring GDP impact and productivity of services industries is needed.

The GDP is a Ponzi scheme, counting capital as revenue.

http://potluck.com/media/the-unsustainability-and-origins-of-socioeconom...

Pertinent to the discussion here, Oil is capital literally burning up until we are forced to account properly. This goes well beyond oil and has been going on for thousands of years in the form of "agriculture". When all real capital has been consumed, whether in an internal combustion engine or from plowing, we are left with consuming each other. The end.

Bacteria, on the other hand, will live on. Collapse from one complexity state to a lower state doesn't mean we have to suffer or even be less comfortable. Relocalization is a start, but don't forget that we know little about how to preserve humus after 10,000 years of farming. Relocalization will be meaningless, if we start burning humus with tilling, fertilizer, and pesticides. If you want coincidences, look at where all the worlds deserts are located and then think about where agriculture has been practiced for the longest. We are just beginning to dig up the ancient ruins beneath the Sahara. That's righ, the weather is responsible. Sound familiar?

Ahh, yes, the great Yellow River desert, so lifeless and barren after expending its soil as the cradle of Chinese civilization that now a mere 100 million people live along its banks...

Truly, the accuracy of your statement is astonishing!

They're lucky, it's a flooding river, like the Nile. A pity they fucked up the natural fertilizing function of the Nile by building the Aswan dam. China is making the same mistake.

Take a look at the cradle of civilization: from Marrakesh to Multan the landscape is indeed barren. Where once the mighty cedars of Libanon grew, now only dust remains.

Look at our works, ye mighty, and despair!

One example of a cradle of civilization is now a desert; another example is still highly fertile.

Ignoring the second and claiming the first represents a general trend is known as cherry-picking, and represents a very biased and partisan approach to the data.

Unless it really is a general trend, of course. Which I believe is the case: Wherever ancient civilizations appeared, when they disappeared they left scorched earth. The exceptions are where large rivers replenish the soil supply, most notably the Nile, the Tigris/Euphrate, the Ganges and the Yellow/Blue river.

So if those four are counter-examples -- and they involve the cradle of western civilization and the cradle of eastern civilization -- then what are the examples of this actually happening? For something that "really is a general trend", I would assume there are dozens of examples of agriculture leading to massive-scale desertification; what are they?

(I'm also surprised you listed Tigris/Euphrates as a counter-example; I was under the impression that part of the reason for the decline of Sumeria was lowered agricultural productivity due to salt accumulation on the field from their method of irrigation.)

Well, the whole of the Mediterranean (the Greek and the Spanish didn't make their fleets out of the present-day mediterranean vegetation) and the Middle East (the cedars of Libanon, North Africa: the bread basket of Rome). Each time the soil in Mesopotamia became bad enough, the current empire retracted and after a few floodings it was ready to go again.

And farming might be sustainable for millennia in its current form, that's not enough. It must be sustainable practically forever. Even as little as the loss of 1 mm of soil each year is 1 m per millennium. That's unsustainable, the exact period that it goes on depends on the soil supply. How much soil has disappeared in the Dust Bowl area, and how much is left? We can be certain that that kind of agriculture in that area is *not* sustainable.

We're talking about food, not forestry. And Spain is a net food exporter, with a vastly larger population than it had in the days of the Armada, so I really don't see that it supports your claim.

Italy and Greece would be better examples -- both are net food importers -- but both have strongly increased their food yields over the last decades (Italy, Greece), allowing them to support vastly larger populations than in their empire years.

Egypt currently produces enough food for about 2/3 of its population, or about 50 million people. i.e., Egypt alone could feed 80% of the Roman Empire circa 300AD; North Africa could still be the breadbasket of Rome.

In fact, almost every major agricultural area currently supports many more people than it ever did in the distant past. Even Iraq produces millions of tons of cereals, despite its agricultural capability being degraded by successive wars and sanctions, which is most likely more than it produced in Babylonian times.

In fact, the strong trend seems to be that ancient breadbaskets are still strong producers of agricultural goods, which is directly counter to your argument.

One way or another, farming 1,000 years from now will be very different from farming now -- the odds that we'll be at a comparable level of technology are vanishingly small.

I do agree with you that we should avoid long-term damage or degradation to our fertile lands, though.

Of course the yields have increased due to mechanization and chemical fertilizer. What the yields would be now with ancient methods is speculation, though I speculate 'a lot less'. But both mechanization and fertilizer are dependent on limited resources, that are not impossible but very hard to replace, indeed, and will certainly become more scarce in the mid-term future.

So I think we can conclude that long-term agriculture is not impossible, but far from a happy-go-lucky endeavour.

(I appreciate the follow-up of the discussion.)

I'll agree with that.

And that. :)

Yes! Irrigation and plowing release salts that can otherwise coexist in the soil without a problem. Watch the video:

http://www.permaculture.org.au/greening.htm

Those are hand fulls of salt he is showing you from Jordan. So where did he put it? "It's not supposed to be possible", they told him. With agriculture, it isn't and you get desert.

The process depends on the soil and ecology being damaged. Grasslands are the most vulnerable, but that is what you get when you clear a forest to grow yet more food for a "growing" population. Since the forests are so integral to affecting climate, rain, and increasing soil humus, they take longer, but will become deserts, too. Bring the forest back to the yellow river and it will run clear, again.

225 days of the year? Five times as much irrigation as done in 1950? There may be 100 million people there for now, but look at the Sahara for where this ends. The river is "yellow" from the soil washing away. Only clear water runs out of a healthy ecosystem. Those dust storms settle over the Rocky Mountains. The process takes thousands of years, but ends the same way as seen all the way from the Sahara to the Gobi and moving down the Yellow River to the ocean for 225 days in one year alone.

Why do you believe that? What evidence do you have for the assertion that long-term agriculture must inevitably lead to desertification?

The Yellow River has been surrounded by extensive agriculture for something like 6,000 years. If it hasn't become a desert in that time, why should we believe it'll do so any time soon?

Again, an assertion for which you provide no evidence. The Yellow River (which is, indeed, named for the large amounts of soil it carries) hasn't had its name changed recently: it's been the Yellow -- carrying vast amounts of soil -- for thousands of years.

Again, if it's been doing that since the beginning of history, what's the evidence that'll cause a problem any time in the forseeable future?

Maybe you're right, maybe the 6,000-year history of agriculture around the Yellow River is going to come to a crashing halt in the next few years. Without compelling and objective evidence to support that proposition, though, a disinterested observer has no reason to believe it -- the 6,000-year history of the Yellow being bountiful is pretty strong evidence you need to counter.

Especially considering that the land 90% of the river's silt comes from ain't farmland.

The Chinese have practiced fertility management over the ages much more effectively than most of the world. This hasn't sheltered them from famines (only experienced with agriculture), but their land was in decent shape in comparison to other areas when the industrial age began.

Agriculture, being a business, has been well documented through the ages with hard numbers. The pattern is decline, until a new understanding helps put depleted land back into production. These days we speak of hybridized seeds and GMO; 80 to 200 bushels per acre for various grains. Previously, we spoke of deeper tilling and a new understanding of fertilizers; 20 to 30 bushels per acre. Before that they abandoned a field when it produced less than 5 bushels per acre. This is just the recent 200 years of history. Part of what drives this happens as the farmers get squeezed for cheaper food, causing them to rotate one less field or some other short cut when innovation fails them.

For reference, much of what I am referencing comes from Masanubo Fukuoka's work in Japan. Although he calls his work "do nothing farming", it would be a misnomer to think this means that nothing is done. "Doing nothing" mearly represents the ideal case, or Mu. In grotesque summary, the acts of tilling, fertilizer, weeding, and herbicides have all proven to diminish crop yields. His yields were in the 30 bushels per acre neighborhood (no till, weeding, fertilizers, and near zero labor, virtually left wild, but with subtle and well timed day or two efforts). Before you point to the efficiency of today's yields, remember that he doesn't rotate fields, plus he has multiple grains producing on the same acre. His effective yields are comparable to today's high energy efforts with little to no labor (work smart).

Recent revelations in soil ecology explaining the gist of what Fukuoka's research reveals:

http://www.energybulletin.net/23428.html

You can practice hydroponics out in a field as long as you can keep up with the increasing labor requirements. The problem is keeping up with the work you make for yourself in subsequent years based upon a finite resource. Increases in energy perpetuate the pyramid scheme.

We know this is how soil functions, because we know how to directly reverse it. We don't even mind that you have hand full's of salt on the remaining sand:

http://www.permaculture.org.au/greening.htm

China would have been able to keep going with famine cycles for much longer, had they not adopted the hybrid seed, fertilizer, and herbicide regimen. Look into their child swapping traditions to get an idea on how common famines have been over the ages.

Then methods clearly exist for agricultural practices that are sustainable over millenia. QED.

The question is not whether current industrial agriculture is sustainable; the question is whether agriculture is sustainable, and 6,000 years of farming in some places -- as well as Fukuoka, Ingham, and similar agriculturalists -- suggest that it can be, if one uses sensible techniques.

Any evidence for this claim?

I'm guessing not, especially since extensive research on this shows you to be utterly wrong:

"With an extensive database on nutrition and food availability in preindustrial societies, which was compiled in the 1950s, Benyshek and Watson compared twenty-eight hunter-gatherer societies with sixty-six agriculturalist societies. They detected no link between lifestyle and amount of available food, or between lifestyle and frequency or duration of food shortages. Feast-or-famine cycles were probably common throughout human prehistory, and they may indeed favor thrifty genotypes, the anthropologists say. But the cycles seem to have been equally likely among foraging and farming economies. (American Journal of Physical Anthropology 131:120-6, 2006)" (link)

Just because you believe something doesn't mean it's true.

I saw an apt quote in the Internets a while back: "Beware the man of one book."

Many people have a bias, and many people do...less than objective presentations of their observations. I'm sure Masanobu has done some fine work -- and I agree with a certain number of his (less spiritually-based) views on sustainable agriculture -- but I'm just as sure that he's not presenting a full and unbiased view of agricultural practices.

When a man talks about science as if it's a bad thing, I begin to suspect that he may not be giving me a fully objective appraisal of the situation. That doesn't mean he has nothing valuable to say (he does), but it does mean that one needs to be careful to accumulate a balanced perspective.

The problem is that there is no evidence to support the claim that famine happens to Foragers as much as it happens to Agrarians, or that it ever happened to Foragers. You are asking for a proof of a negative. Could you speculate that it happened? Sure, knock yourself out. That's what the article you posted says that they did ("probably" and "may".don't mean they have any basis to state such a thing as fact).

Here's a plausible scenario: Super volcano blocks out the sun for a year.

In this case, for farmers, the crops will surely fail, or be delayed for a year, and surplus must be relied upon. The foragers have a lean year ahead, along with all the animals that they can survive by eating almost exclusively. Many edible bugs will be unaffected, so a change in foraging style will be needed for a time. If you think the Foragers are vulnerable in this sort of crisis, then you don't know much about Foraging. Several animal food sources will be unaffected. For agriculture, no sun for a year would be very bad for the population, as not enough surplus will be available for such a disaster. In fact, famine often coincides with food distribution issues, not as much crop failure. Floods and drought don't affect forests to the extent they affect a field of exposed dirt.

Don't ask for a proof of a negative, it just happens this way, due to the water retention and self-circulation of forests. I already gave you a source for this from Energy Bulletin. Remove the forest and you get drought. Drought cycles translate to famine cycles. The drought eventually becomes semi-permanent.

Are you saying that science should be trusted implicitly? Beware of "new scientific understanding" coming your way. Science is merely the best understanding given the facts that we know about. This doesn't mean that science should be trusted as if fact. In the case of human health and nutrition, there appears to be confusion within the scientific and medical establishment. As energy reserves deplete - whether tomorrow or years from now, science will be looking for ways to reduce agriculture's energy foot print. Considering their best guess, thus far, is more in line with economics, I'm skeptical about science when it comes to our food sources.

In the meantime, you can go get your hands dirty and see for yourself what happens when you follow science compared to what happens when you follow Fukuoka and Permaculture paths. Don't believe me and don't believe anything you read, but believe what you see and try for yourself. The worst thing that can happen will be that you spend less time at the grocery store. The upside is that you avoid all those medical bills from such poor food choices, prepare an insurance strategy against disaster, and save some money. The labor costs are primarily upfront: land forming, sheet mulching, some tree planting to get things started, and time observing what works and what doesn't.

Fukuoka started out as a respected scientist. As one scientific theory proved to be bunk after another, he became increasingly disenchanted by modern agricultural science. In fact, he became alarmed enough to write books, travel the world, and be quite noisy regarding his view of science as a result of his work. Considering his success using "do nothing" farming with close to insignificant energy inputs matching harvests in his area using modern techniques (hybrids, fertilizers, deep plowing, pesticides) and huge energy inputs, I'll be trying his methodology for myself. I can't grow rice, as he does, but that isn't the point of his work. I'll be starting with groundnuts (Apios Americana) for my own area.

Incorrect. I am clearly and explicitly asking for evidence to back up your claim. If you are unclear on the difference between "proof" and "evidence", I'm sure there are web resources you can consult.

Moreover, evidence certainly does exist; e.g., the paper I cited. It's not proof -- hence the use of words like "probably", but that wasn't the question.

Incorrect.

"Probably" -- in the context of a paper using proper scientific methodology -- means "the balance of evidence supports". They don't have enough evidence to state that the thing is certainly true, but they do have substantial evidence supporting it, and no or trivial counter-evidence.

Your idea of "plausible" obviously differs from mine...and from that of the editors of the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, apparently.

If I had meant to say that, I would have.

Instead, I said that anyone bashing science should be viewed with a healthy level of skepticism. One of the tenets of the scientific method is objectivity, suggesting that a man who bashes science may not be fully in support of objectivity either. Indeed, science-bashing is in modern culture most commonly associated with cranks or religious fundamentalists, either of whom tend to have...less than objective messages they attempt to promulgate.

Not all science-bashers are cranks or fundies, of course, but there is an unfortunate correlation, and hence a prudent observer would take science-bashing as a warning sign to examine the evidence carefully and from multiple perspectives.

Hardly surprising - Pimental reported much the same when comparing organic and conventional farming methods. That's not the point of modern farming practices, though. Modern farming practices aren't intended to maximize yields, they're intended to maximize profit. While linked, those aren't quite the same -- detailing a man to tend every acre personally would undoubtedly raise yields, but would be vastly more expensive.

Which, of course, is one of the reasons I'm skeptical about a terrible dieoff if oil supply falls precipitously. There are well-known farming techniques -- such as Fukuoka's -- that can return similar yields to what we're getting now, but for far less energy input. They require many more man-hours of work, though, but that'd be fine in a "post-peak crash" scenario, since the standard assumption is that many oil-related jobs will be lost, so the extra manpower will be readily available. So all that'd be likely to happen is that food would get more expensive; considering how cheap it is now (in the West), there's plenty of slack for that before serious problems start.

Westexas,

Your idea about the value of things is fundamentally wrong. I'm very sorry to say and I hope you don't shoot me for this, but it is so naive and wrong that it is almost laughable.

* The value of things is what you pay for it.

* It doesn't matter if you can touch it or not.

If you think an item you can touch is worth more than a service you cannot touch, then you would be willing to pay more for the item you can touch and less for the service.

I will give another example:

What is worth more?

* a dollar worth of horse manure

* a dollar worth of gold?

or

* a 100 million $ worth of cheap chinese plastic crap

* a 100 million $ worth of a design of a new micro processor from Intel?

Why on earth should we suddenly think the comparative advantage models are no longer valid, just because oil is becoming more scarce & expensive? They have worked for several hundred years before we even discovered the first oil well!

What changed?

Comparative advantage will still work. One of my main points however that if we gain X from trade (due to comparative advantage) with transportation cost Y. If Y suddenly becomes greater than X, why trade that particular product?? Furthermore, we are probably dependent on some products that would qualify in this example.

If we can have an infinite growth rate against a finite resources base, nothing will change (other than perhaps the climate).

If we do live in a finite world, an ever greater percentage of the national income will be spent on food and fuel, which will cause spending on discretionary goods and services to fall.

I simply offer the following advice, which you may of course follow, or ignore, as you wish:

Try to live on half or less of your current income.

Try to minimize the distance between home and work to as close to zero as possible, and commute by walking and/or mass transit.

Try to become, or work for, a provider of essential goods and services.

A case history of forced energy conservation follows. What happens when the following situation moves up the food chain: "Soaring energy prices are moving those necessities out of reach, reversing hard-won economic strides."

http://www.energybulletin.net/22775.html

Published on 18 Nov 2006 by Wall St Journal. Archived on 23 Nov 2006.

As Fuel Prices Soar, A Country Unravels

by Chip Cummins

How long ago was it that global trade was sailing ships and 'Empire'?

I recall from the 80s that a Japanese company - I think it was Fuji Heavy Industries flying the Subaru flag???? - made an industrial size catamanan or wide body type sailing cargo boat with hydraulic actuation servo sails and an auto sailing system for testing in the Pacific. As long as you don't mind the backhaul going via Hawaii, it would move a lot of stuff from Japan to NA. At some point, the question arises...

Anybody remember this? I may be confusing it with the Subaru freighter that Subaru down the side.

There have been several attempts to ressurect sail propulsion for cargo ships, but none of them have really gotten very far.

While you can greatly reduce the labor involved by using all sorts of high-tech controls and airfoil sails, the inherent drawback of sail propulsion still remains: you often have to take a longer, more roundabout route to take full advantage of wind direction and speed. This results in a trip of longer duration, and that eats into any savings in fuel. (There have been many accounts of large windjammers taking over a month to go around Cape Horn from east to west because the wind just wouldn't cooperate.)

Of course, this is less of a problem with a ship that is primarily engine-powered and uses the sails only as a boost when the wind is right. During the period of roughly 1850 to 1890 there were many ships that were both engine- and sail-powered. The main reason was that the early steam engines were highly inefficient and not very reliable. However, the marriage of steam and sail was never a very happy one: the engine and fuel represented dead weight when not in use, and the masts and sails when not in use also represented dead weight as well as added wind resistance even when furled.

The other thing is scale. A 3,000-ton sailing ship was a very large sailing ship, and it took a huge spread of canvas to get any decent speed. A 50,000-ton container ship is much too large to propel soley by sail, and even an enormous spread of sail is going to produce only a small fraction of the power required.

I just have a hard time being bullish on large sailing ships.

Wouldn't it be the case that a cargo ship could simply slow down and improve fuel economy?

Yes, in principle that is true.

The energy required to move a vessel a given distance through the water increases very roughly with the square of the speed (accordingly, the power required goes up roughly with the cube of the speed). The reason it's not exactly the square of the speed is that the energy consumption has two main compontents: energy expended in overcoming friction between the hull and the water and energy expended in wave-making as the ship displaces water. The two don't vary in the same way and are dependent on hull form, so it gets a bit messy.

The trade-off, of course is between making a large number of trips per year at high speed or a smaller number of trips but with less fuel consumption. I suspect that right now, the average speed of a large container ship or super tanker is pretty much optimized to take those factors into account. I believe the average speed of a super tanker is only about 14 or 15 knots. Given its very blunt hull form, I doubt it could go much faster than this without requiring an enormous amount of additional power.

As fuel costs increase, we just might see a slight reduction in cargo ship speed but probably not all that much.

A friend who is a former merchant marine officer tells me the last ship he was on was a cargo ship running a touch over 60,000 tons. At 15 knots speed, it burned about 29 metric tons (approx 174 barrels) of bunker fuel per day. At 12 knots they burned about 15 metric tons per day.

At $270 a metric ton, the fuel savings from slowing from 15 knots to 12 knows would be $3780 per day. However, trips would take longer (about 4 days from Los Angeles to Shanghai, for example). Less fuel per day, more days burning fuel. LA to Shanghai the savings in fuel would be somewhere around $37,000. Fuels savings could, however, be offset by added costs in other areas of operations resulting from slower transit times.

IIRC, in the heyday of the fast "clipper" sailing ships, the record for the shortest time for San Franciso to Honk Kong was about 30 days, for an average speed of a bit under 8 knots. Modern technology applied to sails and sail handling and such could add a bit to that, but I suspect sail-powered cargo ships would not average much over 10 knots.

FWIW, when I was on an oil-fired aircraft carrier we used to burn 2500 to 3000 barrels a day, depending on the available wind and the amount of time spent conducting flight ops. We normally averaged 13 to 15 knots. At max speed (above 33 knots) we burned somewhere around 24,000 barrels a day or about 5 feet per gallon.

thank you for that info. out of curiousity - how many days of fuel can fit on an aircraft carrier (how often do they need to refuel?)

Of the 12 carriers that the U.S. has in service all but 1, the USS Kitty Hawk (Due to be decomissioned in a year or 2), are nuclear powered.

The fuel constraint for them would be the jet fuel they carry for their aircraft, which is on the order of 3 million gallons.

The CV-63 class of which the Kitty Hawk is one has an official range of 12,000 nautical miles at speed of 20 knots. At that rate it would need to fuel every 25 days

Great essay!

I especially appreciate your mention of capital mobility; this is not something that Ricardo anticipated and it very much changes the equation. The ability to rapidly move capital(and the actual industrial plant) deprives regions(and the workers who live there) of the benefits of comparative advantage; all the benefits accrue to the owners of capital. Just another breach of the social contract.

Wait - doesn't Ricardian analysis strongly imply the movement of capital?

In the example given, the cheese industry ends up entirely in Wisconsin. Cheese plants in North Carolina must be closed. In addition, cheese production in Wisconsin increases, implying a probable requirement for more physical plant. This makes relocation of plant equipment conceivable, although it depends on how much of the North Carolinan cheese industry can be profitably salvaged.

In a weaker sense, I would expect that at the minimum, it will be more profitable to produce cheese in Wisconson, and investment will follow that profit out of North Carolina.

Are you arguing that this indicates a failure of the social contract because (1) North Carolina no longer benefits from the cheesemaking industry or (2) Wisconsin derives no benefit from increased cheese production? I see no other way that the owners of capital can receive all the benefit.

What the post needs are some real dollar numbers on transportation costs for imports. From the graphs, you can, however, surmise that air freight has a poor future, except for essential goods with a high value and low weight. You could also predict that non-perishable goods transported from Asia by ship will not lose their comparative advantage until oil prices are extremely high.

Here's a quick back-of-the-envelope calculation for marine transport:

- 411 BTU/ton/mile (per Nate Hagans' post)

- 130,000 BTU per gallon of fuel oil

- Fuel oil at $2.50 per gallon

- Trip from China - approx 6,000 miles

Fuel expended = approx 19 gallons per tons

Cost of shipment from China = approx. $48/ton

A ton of iPods or cell phones might be worth a couple hundred thousand dollars, so even if fuel quadruples in price, it is not going to have much of an effect on the import of such high-end items. But it might put a crimp in the import of stuff like plastic swizzle sticks, though.

This effect might be more significant than it at first might look, as countries like China have a greater competitive advantage in making the labor-intensive, low-value crap. If they can't export the low-end stuff due to fuel, they could be hurt pretty badly.

I have to agree with you. Even if you transportation cost increased by an order of magnitude, few products that we actually NEED would get much more expensive. The low-value ones that would, we can live without. The hardest hit nations will be those which export fruits and other low value/weight agricultural goods (that might include the US...). China will be fine for two reasons: first, they are already building internal markets which will fan much of the demand in the coming decades, second, they are set on producing high quality goods and have numerous succesful programs going to take leadership in the production of these in the future (I have seen much more interesting high quality cell phones for exclusively Chinese sales at electronics trade shows than can be bought in any store in the US, this development is similar to Japan which has a very different set of products for their home markets than for export). China understands where this ship/train/truck is heading and its goal to become a country that can hold its own in any comparison with the US/Europe/Japan is perfectly compatible with rising transportation cost.

I think Nate must be seeing the writing on the wall, himself, by chosing as examples Wisconsin and North Carolina. Unless we'll have more transportation on trains between states, interstate commerce will suffer, because getting high quality goods from China to California on a ship will always be more profitable than getting potatoes from the East to the West Coast on a truck.

IP,

Actually, yours is a double whammy.

Please allow me to parse out the issues:

1. Price versus criticality of supply,

2. Price versus marginal utility

In the case of analyzing item number (1) Price versus criticality of supply, one should not fall into the economics "framing" trap of confusing price with security of a steady supply. Say the price of global oil drops to $40/bbl --just for fun; BUT a new big hurricane Cathrina (Katrina's sister) hits the USA Gulf Port area and wipes out the USA ability to import crude via that route --or a terrorist bomb blows out the LOOP --whatever.

The global price of oil should actually drop because there is one less global customer for that stuff --the USA.

However, inside the USA catastrophe would strike because even though the economic "price" signal is heading down globally, you can't get any of that stuff locally. So there is a first mistake in analyzing everything purely from an economically "framed" point of view. Proportional price of an ingredient is not the problem if that ingredient is essential for the final product (or service).

Along that vein, for certain kinds of local enterprises, oil is a critical (essential) feedstock even if it does not make up a major portion of the final market price: Plastics for example. How are you going to manufacture sterile medical devices made out of plastic if you cannot get the feedstock? It's not about "price", it's really about breaking the weakest link in the chain even if that link is "low priced". The whole chain collapses anyway.

On item #2, I'll let Sailorman or one of the other economics professors explain to you why the things we "NEED" (i.e. water, food) end up being the cheapest things in a free market economy and the things of least marginal utility (i.e. tickets to see Mick Jagger's last road tour) end up being the most expensive. :-)

"BUT a new big hurricane Cathrina (Katrina's sister) hits the USA Gulf Port area and wipes out the USA ability to import crude via that route --or a terrorist bomb blows out the LOOP --whatever."

PO is not like a hurricane at all. You know about it for the past 50 years. A hurricane you can't predict two weeks in advance. You can, however, predict that there might be a hurrican and so you double up on your infrastructure (i.e. you got more than one port, multiple refineries etc.). Doubling up on oil infrastructure, on the other hand, will not do anything about PO. This is a pretty poor analogy, if you want to use it that way.

"However, inside the USA catastrophe would strike because even though the economic "price" signal is heading down globally, you can't get any of that stuff locally."

Except, of course, that a scenario where the rest of the world has oil but the US does not is about as likely to happen as that asteroid hitting earth... are we competing in a "unlikeliest of events writing contest"? I for one, am not. I see the average price of oil rising substantially over the next few years and it will rise the same for pretty much everyone who does not live in an oil producing country.

"Along that vein, for certain kinds of local enterprises, oil is a critical (essential) feedstock even if it does not make up a major portion of the final market price: Plastics for example."

What about plastics? Any organic chemist can make them for you from coal, water and a few other ingredients from scratch. You start with converting water over coal to hydrogen (and CO/CO2). Then you take that hydrogen and some more coal and make methane. You partially oxidize methane to methanol and formaldehyde. From these three single carbon compounds you can work your way up the chain to any monomer you like and produce any plastics you need. It's expensive... buy hey! You burnt all your oil in your SUV... what can I do but to tell you how to replace it with what you have? (And I only mentioned one way of going at it: other ways would start with ingredients like starch and sugars, proteins, natural rubber etc.). But before we ever start losing our ability to make valuable medical plastic parts, we will probably start mining for plastic bags in our dumps, anyway. That might be a lot cheaper for a long time than bottom-up synthesis or even synthesis from natural products.

"It's not about "price", it's really about breaking the weakest link in the chain even if that link is "low priced". The whole chain collapses anyway."

You are right, in principle. What you overlook, though, is that induestries are not one dimensional chains of events. They are more often meshes of different production methods, recipes, suppliers, etc.. There are not many things that can only be made one way. What you simply lack is the knowledge about all the different alternative ways people have figuered out to make stuff. Even two products which look alike and have the same function but where made by different manufacturers might not share a single common procedure in how they are being made. But typically unless you are in that particular industry you are not very likely to know anything about these things. That is forgivable. What is not forgivable is to make an argument that solely relies on your ignorance of how things are being made.

"On item #2, I'll let Sailorman or one of the other economics professors explain to you why the things we "NEED" (i.e. water, food) end up being the cheapest things in a free market economy and the things of least marginal utility (i.e. tickets to see Mick Jagger's last road tour) end up being the most expensive. :-)"

The things we need are by no means cheap. If that is what you think, you have little understanding about economy, yourself. Water in California, for instance, is by no means cheap. The cost for much of the infrastructure we need to supply it just happens to have been paid for by the generations of our grandparents and parents who built large parts of our water supply systems with their tax dollars. To create the farms that supply our food required the investement of lifetimes of your ancestors. They paid in sweat and hard work for it but you seem to be forgetting about that. The same is true for all our industrial infrastructure. It did not just pop up and was there for us to use. Somebody had to work for it.

In short: every substantial change of society and technology requires the lives and work of a whole generation.

Our lives will be filled with paying for the change from an oil dependent society to one that is powered by renewables. It will be expensive but in comparison to the backbreaking labor of our forefathers, it will be nothing.

How comes I know these things and you don't? Maybe you should add industrial and agricultural history to your repertoire? Economy alone doesn't quite seem to cut it.

This reminds me of Frank Herbert's Dune Chronicles:

"The Spice (Oil in this case) must flow!"

He who controls the Spice controls the universe.

He who has the power to disrupt/destroy the spice flow controls the universe.

How true it rings...

Cheers,

And in one of those continuing "coincidences," we are seeing a massive increase in the US military presence in the Middle East.

westexas syas :

And the invasion of Dune by the Emprie has begun!

The analogies with crap SciFi are only skin deep. Energy, unlike "spice", can be produced copiously using solar and wind energy. That is even more true for the US which geographically has some of the best solar sites in the world, and again is a winner. All you need to "make" endless energy is a desert and a few mirrors, a hot water boiler, pipes and a steam turbine/generator. The only "magic" here is that you actually have to do it rather than elect morons for president who waste your tax money on war.

Your cornucopian assumption ignores the huge scale (1000's of sq. mi.)of these "few" mirros, their questionable energy return (compared to petroleum), intermittency and backup, the ecologic impacts, and the lack of political will to actually fund it.

These ommissions render your fiction much crappier then one my fondest novels.

This helps put it in perspective...

I used 350 TRILLION BTUs????

Let's see... there is some 3400BTU/kWh, right? So according to this I was using 103 million kWhs last year... that would be 11.8MW of average power in my name. At 15cents per kWh, I would owe $15.4 million on my energy bill...

I guess it should have been "Billions of BTUs per person per year"?

That sounds more believable. Looks like this government can't get anything right. Or am I missing something?

"Your cornucopian assumption ignores the huge scale (1000's of sq. mi.)of these "few" mirros, their questionable energy return (compared to petroleum), intermittency and backup, the ecologic impacts, and the lack of political will to actually fund it."

Huh? Did you fail to actually inform yourself?

1000 square miles equals a 32 mile square. Please get yourself Google Earth, open a satelitte map of one of the deserts in the US and draw a 32 mile square in there with the measurement tool. Then zoom out... At what "altitude" does it become so small that it practically disappears.

Of course, you can just put a few solar panels on your roof. That would work, too. EROEI of PV is on the order of 5-10. Industrial thermal solar power plants are much better. Please inform yourself.

Energy return compared to petroleum? Petroleum does not have an energy return. Once its gone there will be no more... how do you calculate return on something that is not available? Just curious...

"intermittency and backup"

Thermal plants can store wast amounts of heat and steam at the daytime if necessary and they can be operated in conjunction with other sources, e.g. a coal burner to improve overall power plant efficiency. Solar electricity can be stored with hydroelectric storage facilities and solar energy can be used to produce hydrogen directly, from where you have any number of options to generate power during the night or when the sun does not shine. Until solar hits some 15% electrical of peak load, intermittency will not be an issue because the current power infrastructure can absorb it. Intermittance with solar generated fuels is not an issue at all because fuels can be stored.

"the ecologic impacts"

Not any worse than if you plant wheat and corn all over the midwest. Oh, that's right... aLL agricultural areas we use have already been destroyed by settlers... there used to be trees, switchgrass and bisons there...

I think we can do a lot better than our forefathers. Especially with PV on rooftops.

"and the lack of political will to actually fund it"

The political will is where the money is. Wind and solar are a $30 billion market today. They are growing at 30% year over year. Ten years down the road politicians will be standing in line to get money from these companies.

"These ommissions render your fiction much crappier then one my fondest novels."

Looks like you are not only not reading up on renewables but you also fail to have good taste in SciFi. To be honest: I think you care way more about me calling your beloved book a pile of crap than you care about energy issues...

:-)

You cornucopeans have no notion of scale. A simple calculation suggests a 1,000 mile square of sterling engines would cost $56,320,000,000--5 times greater than then the entire Gross National Product of the United States of America

1 engine per 500 sq. ft.

Cost per unit (under mass production) $10,000

88 per acre (44,000 sq. ft. per acre)

56,320 sterling engines per sq.mile (620 acres per mile)

56,320,000 sterling engines * $10,000

Your math and analysis is no better than your taste in literature. May you suffer the indignities of the gom jabbar and lie as fodder for the Shai-Hulud: the Great Worm.

US Gdp is $13,000,000,000,000. You were off by a factor of 200, however your general point is still valid (but not the worm part)

I realized that after I posted. I hope the worm-hunter doesn't notice

Let's take another cut at that. Say that each american is piggishly using about 4kW electricity steady state, all uses included. And since the sun is shining even in N Mexico only about 1/4 the time, each american pig needs 16kW rated power sitting on the ground. A production stirling engine and its rest of system will cost about 500 dollars per kW. Assume the land is free since that 3 sq meter/kW mirror provides welcome shade to all those gila monsters, and cactus don't vote.

So then the cost of plant per person is $8K. That's cheap, given that we can then go chuck all those nasty coal plants and substitute just a great big long fluorescent pink extension cord from NM to the banks of the Ohio.

Now, all you gila monsters- relax- try to read this as just a joke, huh?, I'm goin' to bed.

You cornucopeans have no notion of scale. A simple calculation suggests a 1,000 mile square of sterling engines would cost $56,320,000,000--5 times greater than then the entire Gross National Product of the United States of America

Uh, NOT. $56.3 billion is barely 1/10 of what the United States government spends on the MILITARY every year. Your argument is completely wrong, unless your point was that the United States could EASILY construct a 1,000 mile square of stirling engines by changing spending priorities.

About one year of our current land war in Asia, no?

:(

"All you need to "make" endless energy is a desert and a few mirrors, a hot water boiler, pipes and a steam turbine/generator. "

Right. So then why do people with manifestly impressive engineering deployment skills and cubic kilometers of capital spend so much freaking money on extracting oil from stupendously expensive manufactured structures over violent, cold oceans?

Wouldn't they make so much more money if they did the easy thing and put mirrors in the desert?

Or perhaps (as is true) the numbers and physics don't work out so well.

The reason solar (and other alternatives) hasn't caught on yet is this: Huge sunk-in capital in the liquid fuels infrastructure. The cost of exploring, finding and producing one extra barrel of oil even under the most extreme conditions is vanishingly small by comparison to the existing infrastructure cost (tankers, pipelines, refineries, gas stations, the ICE auto industry, airplanes...). In econo-speak, the marginal cost of one more barrel is very small, while the ability to sell that extra barrel is almost guaranteed. Profits (and losses) are made on the margin, of course.

When all is said and done PV, H2, wind - all the alternative technologies are there and available right now. The socio-economics are not, however, and will not for as long as the marginal price of liquid fuel for transportation is so low. Cheaper than bottled water...ludicrous taxation policies beget ludicrous results on the ground, both domestic and foreign (as in wars abroad).

Here is an idea: every car registered in the US gets an ATM type card which allows it to purchase X gallons per year at the current low tax price. Anything over that and the owner has to pay twice the price. Marginal pricing for marginal use.

Not to mention that fuel is not the same as electricity.

Well, what would be the marginal price of solar power in your car?

I think that there are essential and immutable thermodynamic reasons why solar power hasn't taken off with an equivalently large industry as petroleum. With an electrical grid there is similarly instantaneous demand---this grid needn't be constructed from scractch---and yet barely any solar. Wind's better, but still all wind + solar equals one large nuclear installation.

What is the cost of using solar power to make liquid hydrocarbon fuel? Make it fair--so the rest of the infrastructure is there.

"Here is an idea: every car registered in the US gets an ATM type card which allows it to purchase X gallons per year at the current low tax price. Anything over that and the owner has to pay twice the price. Marginal pricing for marginal use."

I envision many wealthy SUV users buying junk cars and parking them permanently to get their gasoline allowance.

huangrx -- I think that the analogy works pretty well.

"Spice" is not exactly analogous to "petroleum" but it is pretty darn close.

Whether we (or stuff) are moving around the planet or around town, it is generally because we have petroleum.

I am finishing up Frank Herbert's trilogy ("The Jesus Incident," "The Lazarus Effect," and "The Ascension Factor") wherein humans seem to have jumped the hurdle regarding production of energy, but are essentially in exile from planet earth because of changes in the sun.

Even though humans had learned better ways to get energy (largely electric energy) they were still plagues by war and violence. In fact, control of the food supply seemed to stand in an analogous position to "spice" or "petroleum."

Our military monitors and "secures" oil in exactly the way that spice or food are secured and used as instruments of ultimate control in Herbert's science fiction.

As WT noted, the current gathering of force in the ME is a telling move.

""Spice" is not exactly analogous to "petroleum" but it is pretty darn close."

How so? "Spice" is something that can not be replaces in the scenario of the Dune world. Oil is something I can replace today with electricity from wind and solar. Having to pay more for the same amount of energy is not the same as not having energy at all. It just seems like that if your middle name is "Scrooge" adn you are trying to be like your namesake. Thank goodness most parents don't do that to their kids...

"Even though humans had learned better ways to get energy (largely electric energy) they were still plagues by war and violence."

War and violence are not plagues. They are options people and governments pursue BY CHOICE. No war in the world was ever started by accident. All wars were started by people who opted for violence as one possible solution to their problems. And most of the time it turned out to be the wrong choice. Some people argue that it always turned out to be the wrong choice. Be that as it may... it was always a choice!

"Our military monitors and "secures" oil in exactly the way that spice or food are secured and used as instruments of ultimate control in Herbert's science fiction."

You might want to read more newspapers and less SciFi... so far oil production in Iraq is down from before the war and if we ever wanted to get a return on our investment in Iraq, oil prices would have to go to $1000/barrel. Which would kill our economy, even if we were the only ones to get cheap oil.

"As WT noted, the current gathering of force in the ME is a telling move."

It sure is telling: it tells you that you voted for a moron for president. What it also tells you is that investing the $1 trillion Iraq will cost us on energy efficiency measures would have made the US far less dependent on oil and far more secure.

I'd appreciate it if you'd back off on the aggression, Infinite Possibilities. I've not been demeaning or aggressive with you, and I expect mutual respect if we are to converse.

One can go anywhere on the Internet to exchange insults, and I don't have time for that.

I disagree that you or I can use any technology currently available to replace the energy we get from oil. We have some options for much more expensive, much less return-intensive technologies. Some of these technologies also have even worse environmental impacts than use of petroelum.

If you disagree, great, but I've not seen anything to persuade me of that at this point. Any links or info you could recommend?