The Anglo Disease - an introduction

Posted by Jerome a Paris on June 26, 2007 - 2:02am in The Oil Drum: Europe

This text is meant as an attempt to explain what this 'disease' might be, trying to be as pedagogic as possible. You are my guinea pigs, so all comments and questions are welcome - indeed, they are hoped for - so that this text can be improved upon and refined.

In the Netherlands, the discovery of the large Groningen gas field which brought about a boom in that resource sector, with a lot of - highly profitable - investment concentrating in that sector. The reason that something which sounds like good news is called a disease is that the investment in that profitable sector tends to cause a drop in investment in other industrial sectors, because it is so much more profitable; at the same time, there is a lot of extra revenue from the export of the resource, which generates new demand which cannot be fulfilled by domestic production and gives rise to increased imports. The fact that resource exports grow strongly also tends to cause the domestic currency to get stronger, thus further penalising other sectors of activity on international markets. The result is a weakening of the rest of the economy, and increased reliance on the resource sector.

This then becomes a problem when the new sector is based on finite resources, and eventually goes into decline. At that point, exports dry up, but the rest of the economy, having become uncompetitive and fallen behind, can no longer pick up the slack and has become too small to carry the economy over. Thus the overall economy suffers.

In effect, the displacement of existing activity by the new sector is, to some extent, irreversible, and thus, when the resource dries up, the overall economy is permanently weakened. It's also part of the "resource curse", which usually includes additional symptoms like corruption and weakening of democratic rules as a lot of money gets concentrated in relatively few hands (those that own and those that regulate the resource industry). In the worst cases, it can include militarisation of society (weapons being an easy way to spend a lot of foreign currency and being occasionally useful against those that might want to take your sweet spot overseeing the cash cow).

:: ::

I think that the above is increasingly relevant to describe the economy of the UK and, to a lesser extent, that of the US, which are increasingly dominated by the financial services industry.

That prevalence of the financial world is no longer a matter of dispute. In fact, it is celebrated with increasingly euphoric words in most business publications and current affairs books. There is an air of hegelian (or marxist) inevitability about the triumph of markets and Anglo-Saxon capitalism, led by the powerhouses (banks, hedge funds and assorted accomplices) in the City of London and on Wall Street.

But just as Britain led the world into industrialisation, so now Britain is leading it out. Today you can still find a few British engineers and scientists making jet engines and pharmaceuticals—and doing rather well at it. But many more are cooking up algorithms for hedge funds and investment banks—where in many cases they add more value. The economy has boomed these past 15 years, as manufacturing has been left behind and London has become the world's leading international financial centre. Britain's deficit in manufactured goods is hitting record highs. But so are the capital inflows.The Economist (editorial, this week)

The collapse of the trade balance, linked to the long term (relative) decline of the manufacturing sector is indeed one of the most noteworthy commonalities between the US and UK economies, along with the reliance on the sale of services, in particular financial services:

Unfettered finance is fast reshaping the global economy (by Martin Wolf, senior editor, Financial Times, 19 June 2007)It is capitalism, not communism, that generates what the communist Leon Trotsky once called “permanent revolution”. It is the only economic system of which that is true. Joseph Schumpeter called it “creative destruction”. Now, after the fall of its adversary, has come another revolutionary period. Capitalism is mutating once again.

Much of the institutional scenery of two decades ago – distinct national business elites, stable managerial control over companies and long-term relationships with financial institutions – is disappearing into economic history. We have, instead the triumph of the global over the local, of the speculator over the manager and of the financier over the producer. We are witnessing the transformation of mid-20th century managerial capitalism into global financial capitalism.

Above all, the financial sector, which was placed in chains after the Depression of the 1930s, is once again unbound. Many of the new developments emanated from the US. But they are ever more global. With them come not just new economic activities and new wealth but also a new social and political landscape.

Sectors like manufacturing have seen their share of economic activity shrink , as many activities were outsourced, offshored or eliminated altogether. The trade balance has gone south, and jobs have disappeared under relentless pressure for higher competitivity.

This might not be so bad if the jobs created in the service sector, and in finance in particular, were as numerous and high paying - and durable as those in the industry. All statistics on median wages suggest that this is not the case: median wages have been stagnant over the past couple of decades, with a stark increase in inequality. Increased wealth (as measured by GDP or average income) has been captured by a small number of people at the top, something strikingly similar to the remuneration structure of big investment banks and the rest of the financial industry.

The inequality might be acceptable if there was a prospect of reversing it as increasing prosperity is created (this is essentially the argument of Martin Wolf and other proponents of globalisation), but is in fact a structural and necessary feature of the system. Globalisation has spawned a whole ideology about efficient allocation of resources, optimisation of investment decisions, and the invisible, but natural, and morally neutral hand that allow markets to reveal the best price at any given moment for any item. It brings along a vicious hate for taxation, and sees government, and its core functions, redistribution and regulation, as something to be avoided and eliminated as much as possible, being fundamentally anti-efficient. It also brings the core idea that only things that have a price have a value, that everything can be measured in dollars, and that what isn't so measured has no worth nor legitimacy. It fosters a culture of individualism ("freedom") and consumerism ("success"). Social policies (which require distribution), common goods (which need to be defined and managed) and non-economic measures of well-being are spurned and actively fought. Growth is paramount.

While I think that this is more than enough to disqualify neoliberalism (as I have mande abundantly clear in many earlier diaries), there is actually worse. and that's where the concept of the 'Dutch disease' comes in.

:: ::

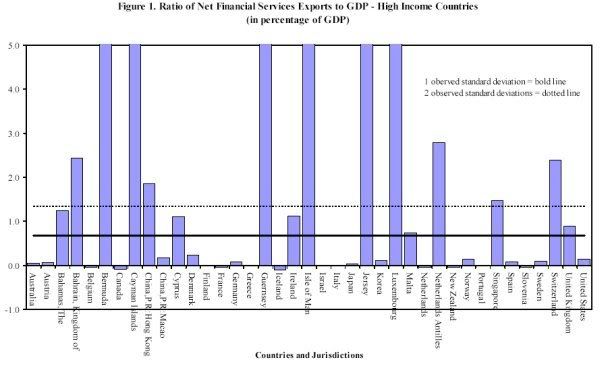

One of the core triggers of the Dutch disease is that the resource sector which has unbalanced the economy eventually shrinks as the underlying resource is depleted. In our case, the industry that causes activity-substitution (finance) can appear to be able to grow ad infinitum, without any limitation to actual resources. Just borrow more money to do bigger deals and enjoy the very real income taken along the way. Find another lender to refinance or another buyer to re-purchase, and you're home and dry. Or just do deals where the actual burden to repay is pushed back into the future (and you won't be around anymore if and when they falter). Thus the City and Wall Street can appear to generate more jobs than the industries they kill off destroy. In addition, with New York and (even moreso) London dominating finance worldwide and not just domestically, they can create jobs and capture wealth locally while imposing their requirements on companies and activities in other countries, thus creating little or no pain at home (see the graph below on how the UK as a whole can be defined as an offshore financial center, just like any Caribbean Island...)

But in fact, this is but a transitory phenomenon, underpinned by a single underlying factor: the long decline of inflation, and thus of interest rates, over the past 25 years.

We've been living in a long, massive bull market for bonds, born off the inflation of the 70s, and the grand ride which was made possible by the new financial tools offered by the IT revolution and by Reagan/Thatcher inspired deregulation is about to come to an end. The returns we've grown used to were just a long but temporary phase in a natural long term economic cycle, and, despite the final boost provided by 'Bubbles' Greenspan in the last few years, not something that can be sustained on a permanent basis. Put simply, it is not possible to generate 15% per annum returns on capital forever when the underlying economy is growing only by 3%.

As the interest rates go up again, and liquidity tightens again, the financial industry is going to run out of the underlying resource that sustained it - easy and plentiful access to money. As that constraint imposes its implacable discipline, and the financial industry finds out that it no longer has anything to offer to its clients (trading stuff, or trading imaginary products remotely backed by stuff, will no longer be so much more profitable than making stuff), it is going to shrink and withdraw. And the countries and cities that have bet on that industry for their prosperity will face the resource curse, as their core activity loses steam and alternative activities, having being neglected for so long, no longer exist or are too small or uncompetitive to make a difference, and cannot pick up the slack. This is what I propose should be called the Anglo Disease.

As this reversal has not yet taken place, and as this prediction threatens the livelihoods of many of my readers, I expect to be mocked and dismissed, but bear with me and help me work on the concept.

I hope to expand on the idea in further diaries, and I hope to get your feedback (including questions if you're not sure you understand what I wrote - maybe I am actually talking nonsense, for all my apparent trust in my assertions). The topic ties in neatly with the critique of neoliberalism I've been trying to write about in the past, to our unsustainable focus on growth as a sign of success, to worries about resource availability, and to the "inevitability" of the Western model - or rather of its financial brat, the Anglo-Saxon capitalist market economy, so there is a lot of matter to write about, and I hope you'll join in the fun.

Jerome:

As I was traveling in Central Texas Monday afternoon I heard over NPR's Moneywatch that UBS had blamed the subprime meltdown on the growing inequality of income in the US, that the working class had been in a recession while the owning class made ever increasing amounts of money. This is bourne out by the figures of Shadow Inflation-the US has a real inflation rate of at least 10%, while wages have not kept up for the last 25 years for the middle and working classes.

That seems true to me in my small part of the world. At least half of the people in the US are living pay check to paycheck, with their only real asset in their homes. As the prices of energy ,healthcare and food have tripled in the last 10 years, their expenses have shot up incredibly. They then resort to living on high interest credit cards(18-22%) and borowed and refinanced against their homes to pay off their credit cards then refinanced again, successfully turning their current consumption into subprime debt.

We are well into overshoot on this problem-the owners have to realise that if you don't pay people a decent amount, they can't pay their bills and purchase more. And its only going to get worse the longer it is postphoned. Now American car manufacturers are offering rebates and deals where the payments are postphoned for a few months. The consumers take that money and use it to continue the Ponzi scheme of paying the mortgage, paying the credit cards for a few more months before paying the piper.

This is exaberated by the nature of current employment. Th reason that retail jobs and service rep jobs don't pay squat is because they are really not very productive-while the good paying working class jobs have moved overseas.

Its a real conumdrum.

Jerome a Paris,

First, my compliments on what is a fascinating article, and the choice of topic I find very compelling. Allow me to say that in my opinion there should be no danger of you, to use your words in the closing paragraph, being accused of "talking nonsense". I will admit to needing more time to really grasp the nuances of your positions and assertions how ever, but I would still like to venture some inquiries of my own. I hope you continue working the topic of what I take to be your concern aboout "Manufacturing vs. Financial" sector expansion, and the nature of real growth/wealth.

I was told many years ago that one of the most deadly theories in history and the one to be most cautious in using or accepting is "this time, it's different."

But, we have to keep in mind that there are occasions when the statement "this time, it's different" will be true, in other words, that we are not just talking about the standard "business cycle" swing back and forth between opposites (unerinvestment vs. overinvestment, deflation vs. inflation, growth vs. contraction, etc.). After all, we have mechanisms to cope with those. But what is almost impossible to prebuild a mechanism to control is the "revolutionary premise" (Alvin Toffler's term), or the complete paradigm shift.

Mr. Paris, do you see the current period as a time of complete paradigm shift?

Peak oil of course would be just such a paradigm shift, and would basicall junk the normal financial assumptions, i.e., there would be no way to invest in a way that could cover the normal contingencies.

Likewise, let us assume a positive revolutionary premise, say the rapid introduction of some system that would alter production and distribution in a radical way (distributed PV or radical breakthrough in storage batteries leading to super long range electric vehicles and use of renewable energy for instance). While the advance would create massive new opportunities, the "creative destruction" edge of the sword would basically junk out massive wealth producing firms (GM, Ford, ExxonMobil, Chevron, etc.) that are staples of many stock and bond portfolios. In other words, a radical breakthrough in technology/production/manufacturing, the hard money sectors, could have a catastrophic effect on the "soft money" side. In one way, real wealth would destroy what could be called "fiat wealth". Again to use an old Toffler term, we could end up with a "shabby gentry". This actually happened as we know during the industrial revolution, when some stayed locked into the "agrarian" methods of wealth production, while the more liberal and advanced moved on to the industrial model.

The question we must ask is (a)Where to put our money if we simply believe we are in a contraction phase of a normal business cycle (the normal bets have always beeen interest bearing investments, high grade corporate and government bonds, and hard assets (real estate, metals, and inflation hedges), or do we actually take the "this time it's different" bet, and go for the post industrial investments, and if so, what would they be?

The Western model assumes that growth in the industries we now know and are used to will in fact, after a time of contraction, return. If we bet against that, let's admit it, we are taking a huge chance. I once said that historically, to bet against the success of your own culture is very, very painful if your wrong. There were those who actually did it in the 1970's, pulling money out of investments seeing the energy and economic troubles of that period as permanent. When growth returned in 1982, some refused to reenter the markets, thinking it was a dead cat bounce, a scam, etc. They missed the greatest period of personal wealth building in history. Many of the folks that you mention as having stagnant incomes created that situation themselves. They refused to advance educationally, invest in the future (because they believed there really wasn't one) and thus, did not advance financially. Now, they are later in life, with little time left to repair the outcome of earlier bad decisions based on a misreading of the events.

If however, we are on the edge of the "revolutionary premise" (either negative, post peak collapse or even leaving peak aside, the collapse of standard Western models) or the technical blast upward of advanced technology (the aforementioned energy breakthroughs, some type of advanced and cheap "fusion in a jar", etc., then we have to ask ourselves where to position to take the greatest advantage of it. "Safe money" might be anything but safe, while radical plays may be the best bet for wealth accumulation.

The thoughts above are more in the way of inquiry than commentary, because I am getting later in years (49 years old) and really need to read this one right. I am honest about that fact that to this point in life my readings of the future financial picture have been poor. In the 1970's, I was one of those who bet that Carter was right when he quoted the CIA and said "the end of the big oilfields is here, there are no more fields to be found." I assumed nothing good was going to come to the U.S. and world economy in my lifetime, and missed the 1980's-90's runup. By the time I saw how far behind I was wrong and how badly wrong I had been, it was essentially too late. So I went with what I saw as the safe bet, good dividend plays, American electric utilities.

Again, I misread, as this was just before Enron, Calpine, Aquilla, Duke, Dynergy, etc., and I lost most of what I had managed to save. And then, the "revolutionary premise" struck in an instant on 9/11 and I was almost wiped out.

Post 9/11, energy prices slid, stocks slid, and business pulled in it's horns. I completely misread what path our nation would take at the political level. My assumption was that we would pull in our horns, possibly tax fuel massively and call up first voluntary and then possibly mandatory service, i.e., a World War II austerity program. I could not have been more wrong. I assumed that even without that however, it would be MANY years, perhaps two decades before the stock market would get back to where it had been. My guess for the Dow right now, if I had been asked then, would have been somewhre about 9500.

I recount all of this not to bore you (though it may well have that effect!) but to let you know that I am a complete cynic (and I have many friends in exactly the same position, experienced investors who have been wiped out over and over....that's why I often doubt many of these stories about people willing to take risk, and huge liquidity bubbles of easy money....I have not seen them in person, and niether has anyone I know....money has been damm tight where I am, credit....VERY hard to get and at very poor terms, and earned wealth from investments, very seldom heard of) but back to the cynic: I think the Dow for example, in 5 years could be (a) 5000 (b)22000, or non-existant. I think oil per barrel could be (a) $22.00 per barrel (b) $122 per barrel, or non relevent.

I could go on. So as a last question, I would like to ask you what what methold you use to establish rational price on money (interest rates) on stocks, on oil, or on any other commodity? Do you have a way to rationaly say, the financial sector is overbought, or a way to say the manufacturing sector is overbuilt? Because while everyone says we should be in manufacturing, the question is, manufacturing what? Are we not over capacity in every sector, from farm equipment to clothing, cars and electronic goods (never mind houses, would we really want more manufacturing capacity there?)

But, back to the fundamental question: This time, is it really different?

Roger Conner Jr.

Remember, we are only one cubic mile from freedom

Roger,

I think I hear where you're coming from. I was first alerted to "Peak Oil" in 2004 - some oblique reference in a news article I read had me do some Googling. I can't say I was overly surprised, more afraid of the prospects for a reasonably large mortgage attached to our house (about 40 minutes drive outside of Christchurch, NZ - it seemed obvious that it wouldn't be good for property values in commuterland ...)

By the end of 2004 we had sold the house (I'm not sure my wife was entirely convinced, but I was losing enough sleep over it). Of course, my crystal ball probably should have had "events may be further away than they appear" etched into it.

I feel as if I've been in a "holding pattern" for the last three years - we're renting, and waiting for the tide to turn.

I'm in IT, and can't see the prospects of getting any return on time invested in projects paying off (either due to the impact of "Peak Oil", or more imminently, perhaps "Peak Debt/Real Estate").

So, while we've cashed up our house equity (as it turns out, perhaps prematurely, but I think I prefer that to being too late), I can't see anything I'm prepared to risk it on at the moment.

The trouble is that I think events in the foreseeable future will turn the economics of just about everything we currently know upside-down. If I decide to, say, invest in manufacturing something now, what's to stop me going broke before things change and it becomes profitable?

Trying to profit on financial investments (taking into account "Peak Oil" and likely outcomes) also seems far too risky. Big losses could be just as easy to come by as big profits. (And something tells me that longer-term bets could be risky even if you win - you also have to collect them!)

So, the "plan" at the moment, such as it is, is simply to keep working (for immediate cash income, not on speculative projects), and wait for an opportunity. Quite possibly, buying a house on a useful-sized piece of land well outside of any major city, assuming prices revert to something half-way sane, and not feasible otherwise. Hardly a detailed plan though, we'll just react to events and opportunities (if any) as they occur.

I wouldn't be too surprised if "Peak Oil" went unnoticed by the majority, as the current global financial bubbles pop/unwind. (I.e. your $22/barrel price could be about right, if adjusted for inflation, for those that happen to have $22 to spare!) Imagine the impact on investment etc., in the oil industry! If the economy ever did show signs of clawing its way back up, it might then hit its head on the limits, at a much lower level?

So, I sit here, watching everyone around me scramble to borrow even more money, to buy more expensive houses, figuring they'd better do it now, before they can't afford to (I suspect they won't be able to soon, but not for the reasons they think). Wondering what will survive, and what won't. What industry will make sense, and which may still have to compete with those trying to wring the last drop of value from their capital investments in China, despite perhaps getting next to nothing for their products? Assuming anyone can pay to ship them here, or anywhere else for that matter. Concentrating manufacturing where it's cheapest is obviously a mistake, but I'm not prepared to wager valuable capital making specific bets against it at this stage!

Meanwhile, I'm just as stuck for ideas. It seems like there should be ample opportunities to prepare, and be better positioned for what's coming. I'm hoping that by not being in debt, and at least expecting trouble, I'll be better prepared than the majority when the time arrives ...

Is this time different? I'd say yes - at least in terms of the financial cycle. The coming "recession" is going to "have knobs on it" ... with or without "Peak Oil". It'll probably be talked about for generations ...

Meanwhile, perhaps I'll wake up one morning to the news that Japanese housewives and hedge funds propping up the $NZ will have realised that figuring the size of the NZ economy, by counting the number of legs and dividing by two, gives a completely different answer if you don't count the sheep. I don't know if that will be good news or bad, but it'll certainly be interesting ...

And thanks to all at the Oil Drum - probably the best of the "Peak Oil" related sites I've come across so far! (Though I won't pretend to understand the more technical aspects!!)

-Ian.

the first paradigm shift was the discovery and for the first time in human affairs, use, of cheap oil.

the second paradigm shift will be forced by peak oil.

Go ahead, Roger. If you believe it is different, bet your money. I'll be betting against you. But by all means, we need suckers on the other end of the bet so if you are volunteering, I won't discourage you.

Ghawar Is Dying

The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function. - Dr. Albert Bartlett

GreyZone challenged,

"Go ahead, Roger. If you believe it is different, bet your money."

Ouch, the old slap in the face with the glove, "I challenge thee to an investment duel...!" :-)

But of course, that's the problem, I don't "believe" it's different, but I don't

"believe" it's not different. Oh the issue of the "great collapse" I am agnostic.

But likewise, on the issue of what could, for lack of a better phrase be called the "great technical cornucopian deliverance", I am also agnostic. I root for it, I think it's possible, I think it's a choice we may be able to make, but will it happen? Who knows. The odds are even at best, and if we delay much longer the odds turn harshly against us.

But the issue we were going to duel on was investment, "betting our money".

I have already admitted to my poor history in investing, and my tendency to sell America and technology short over the last 40 years. I know that you wouldn't think so by some of posts, but I am very cynical about technology for example....it really has to start showing revolutionary advance before i take notice. Most cars for example that do not sell not because they use too much fuel. They don't sell because they are a BORE! Design and technology over the last 20 years has indeed been a failure (on that at least, I agree with Kunstler), but past performance is no indicator of future returns (where have you heard that one? Maybe from the "investment community" who promote everything but assure nothing!).

1. So let us play out scenarios for a few minutes: If I assume this is a replay of the 1970's, then I am in high cotton, as we say in the South, I know just how to bet....split between hard and interest bearing assets, and inflation hedged bets, and buy property with the profits after it crashes throgh the floor. Conventional "blood on the street" investing. Buffet and Trump made billions on it in the 1970's.

2. But what if "this time, it's different". There will be no return to readily available influxes of fossil fuel, there will be a shortage situation driving higher prices and finally spot and then broader shortages. Where to invest, other than in guns and ammo, canned food and a can opener? (I had a person recommend exactly this to me in the 1970's) In other words, is there any future for monetary investment of any type? If we take the full "Olduvai Gorge" theory seriously (I don't, but if we do) then of course we must study the cave man and agrarian village lifestyle, and forget the idea of monetary investment. Again, we have a precedent. Maybe not a happy one for those of us who rely on modern technology to remain alive, but a precedent none the less.

3. The other option would be closer to what I will call, after Alvin Toffler, "The Third Wave" model. This would be a complete and rapid restructuring of Industrial legacy technology, to a changed energy base, a changed manufacturing and service base, a changed informational base, and restructured wealth creation, which would result in a massively changed economic and even social structure.

Option 3 would not mean the end of a modern technical culture. But it would mean a very fast moving "ad hoc" type of creation, investment and yes, even destruction. How one would fair in the post industrial world would depend on how quickly one could read the fast moving situation and invest in it.

Solar? maybe. Which, thermal or PV? Concentrating solar? Which, concentrating lenses on PV cells or concentrating thermal mirriors?

PV? Which, silicon or CIGS Copper indium gallium selenide cells? What about the newest generation of nano and plastic cells? What about the direct water/sun to hydrogen solar panels without electrolysis? Could that really work on large scale?

So when we ask, "Are you going to invest in solar?", we have to ask "by solar, what do you mean"? It will be easy enough to guess right on solar but guess wrong on which format will prevail?

Now, play that same set of complex arcane options out over and over....battery, distributed generation options, wind, electrical power storage options, methane recapture, coal to liquid, carbon control and sequestering, groud coupled heat pumps, solar assisted heat pumps and refridgeration....the list goes on, to the point that it gives you a headache...no wonder people on the doom side say "oh screw it, give me the freakin' stone age, at least I can get some sleep and sex, and no one will gripe when I eat fatty meat!", while the cornucopians say "hey, all this thinking is bad for you but more, it's pointless when we are awash in oil!"

The doomers and the cornucopians have in common that they are both dreaming of a simpler world. Overchoice and complexity are the enemies.

Now, which way will you bet your money? And here I will stop asking and make an assertion: DON'T assume the situation will get simpler and less complex, or that the pace will slow down. Whether you are a doomer or a cornucopian, believing in a simpler age must be viewed as an exercise in believing in fables.

So if you take the true fast crash scenario, frankly, not much matters. Your talking learn to be a barbarian and bring it on.

If your talking the 70's redux, again, you know what to do.

But if your talking what I am assuming is the more likely scenario, a very fast moving, complex, technically advanced, information loaded "ad hoc" economy worldwide, full of organizations and networks, many with no true "standing" in the acadamic world, perhaps even on the outside in relation to the authorities and powers that be, coming into being rapidly, making alliances, raising support and money from conventional as well as unconventional sources (illegal sources in some cases?), buying, designing, licensing products and ideas, and then fracturing, only to be recombined at a into new alliences. This is NOT your fathers corporate stability, but from it, great advances could be made, and technology introduced. Think, as an example of Calcars, Felix Kramer's outfit, the pioneers behind the birth of the "plug hybrid" in it's modern concept. What standing did they have? What right did they even have to be in this industry? How can you invest in them? What will be the contractual obligations of "open source" style energy advances. Who will profit, and how?

So in response to your challenge, "Go ahead, Roger. If you believe it is different, bet your money.", I would reply, my money, what little I have of it, is being bet everyday. (So is yours, by the way) Whether I like it or not, prices are being set, interest rates are moving, the value of what I own is moving, my ability to heat my home or secure food is being decided. The question is, will I attempt to take an active part in controlling my own financial destiny. I can run for the hills, become a modern day Danial Boone...that would be a financial choice. Or I can hedge with the safe bets, i.e., the ones that would have worked in the 1970's, lay low and wait for the good times. Again, a financial choice.

Or I can attempt to learn fast, move fast, and try to read the next wave (it really will be a bit like surfing) and be ready to move and change direction as needed, fast, but with as much information as I can get access to.

Can I pull it off? I don't know. The odds are not with me, to be honest. I am by nature a bit droll and risk averse (otherwise, why would I be here? :-), and have a built in sense of doom of my own to deal with. But one thing keeps hanging in my mind: As I said above, my future is already being determined, I am just not nearly actively involved enough in determining it.

By way of a closing example, I was talking to a friend of mine in the investment community not too long ago, and asking him what he thought of the oil and gas situation. "I don't know, it could go up or down, it's almost impossible to know. Either way....I make enough off energy dividends from shares and partnerships in the energy industry to pay for all the energy I buy."

I know the guy. He was NOT kidding. And do you think he gives the valuable information as to where he finds these deals to his clients? What do you think?

(not spell checked, time limit, sorry)

Roger Conner Jr.

Remember, we are only one cubic mile from freedom

I have given the "great collaps" thing many thoughts, and swung this way and that. I recently start to believe that many of the disputes betewen the collapsionists and the optimists are nothing but mere semantics. Let's take a look at one of the most defining periods of European history: the second worldwar. Can this be called a "great collaps" or not? Was it a die off or not?

Optimists may use this example as well as collapsionist: It

almost wiped the Jews from Europe, it did cost enormous human suffering, the old ethnic make up of the continent was entirely destroyed. Yet within 10 years after it ended half the continent experienced economic growth that was unprecedented. Side by side it was the culmination of old European feuds, a real die off, a total destruction of everything that was, and yet within 20 years the continent was voluntarily united.

The twentieth century was boom, total collaps and die off almost at the same time. Doesn't history largely escapes our narrow models!

But Cheap Energy was available from the US and from abundant domestic supplies of coal. Also massive help from an undamaged superpower was available: Grain , Meat, other foodstuffs and machinary - all these required cheap and abundant energy to get to the right places.

Because the US was rich in all these things and undamaged by war, she was able to put Western Europe on a life - support machine until rebuilt. And, unlike the Warsaw Pact, Western Europe was able to devote less energy to defence and more on rebuilding. The WP had to try and do both with no external help.

The Second World War is not a good guide to this coming event. The only guidance the Second World War can offer is how the people of the UK managed through the Battle of the Atlantic with respect to domestic food production and rationing.

This time, each geographic region in turn will be dealing with its own internal problems of energy loss and critical shortages. Each region will look to its own resources to get through.

There will be no external help as energy abundance and available foodstuffs contract globally.

Do not look for help as none will be forthcoming.

We have not seen anything like this since the decline of the Western Roman Empire.

The only guidance the Second World War can offer is how the people of the UK managed through the Battle of the Atlantic with respect to domestic food production and rationing

And how Switzerland got through a 6 year 100% oil embargo while maintaining a Western industrialized democracy with a decent quality of life. Some lessons from Sweden too,

Best Hopes for non-oil transportation,

Alan

Switzerland was a nice little piggy bank for the Nazis, and never much in need of Oil and with a low population. And a lot of small-holding farms with farmers at home.

Sweden kept a lot of trade going, had a low population and a lot of small-holding farms with farmers at home.

UK was 40 million and fighting for its life. Coal for industry, oil for ships tanks and planes. With a lot of workers in khaki, substituted with land army girls. Markets for finished goods were lost (not that we continued making much as factories converted to war materials)

And of course, the Nazis were not trying to strangle the Swedes or the Swiss.

Not the best comparison I think, but still something to learn from.

Even on a war footing, with victory gardens and massive attempts to feed itself, the UK did not survive without help. Of course, not every ship was loaded with Grain and meat, many were prioritsed for munitions and armaments of all types and fuel.

We are now 60+ million and climbing and have paved stubstanial areas of prime agricultural land especially in the South East and the midlands.

Example 1: Earlier this week the High Court overturned a small group of allotment farmers. They found in favour of the council who wanted to sell the allotments to developers.

Example 2: The flooding in the UK as seen this week is as much due to paving farmland, meadows and wood land as any unusual weather. Actually the weather is not unusual. Its just the 'june monsoon'. Just a bit heavier because of the dry April.

A slow squeeze might allow some mitigation with effort and national leadership and a unity government. A rapid interruption of food and oil flows would be an immediate disaster. We have traded national resilience for just in time efficiencies at every component level of society, from gas storage, to imports of milk, butter and cheese (on an island made of lush grass and rain every other day - we import cheap milk! While UK Dairy farmers go bankrupt on a weekly basis). Most of our clothes and shoes come from Chindia.

So, in summary, Were we to build any kind of resilience in the UK for the times ahead, we would have to turn modern capitalism and economics completely on its head.

As you may well say yourself:

Best hopes for a voluntary return to the resilience of a less efficient, vertically integrated, management - capitalism economy.

O, but that wasn't the point I'd tried to get across. It's more that even in retrospective one can still differ about defining a historical period.

But now that I think about it: The dutch famine of 1944, the socalled "hongerwinter" probably gives some guidance. The German occupier more or less forbade transportation of food.

My perents were kids back then. My father was sent to spend the winter at a farmer my grandfather knew and my mother remembered seeing people die. My mother always thought of throwing leftovers away as a sin. I inherited that somehow, I always reuse leftovers.

I'd like to add to that that the dutch famine mainly occured in cities. This was not a food production problem, it was a transportation problem, even if initiated by the occupying forces. With that regard I find it odd that peakoilers have so little attention for something which I think has even more impact with regard to coming events then mere population growth: Next year more than half of the worldpopulation will live in cities.

To give yo an idea why that fact might have more impact then population growth as such let us take a look at Sofia, capital of Bulgaria. While the overall population of Bulgaria is declining the number og inhabitants of Sofia is actually increasing.

O dear, me and my big mouth..

http://www.theoildrum.com/node/2720#comment-206542

The 20th century was never dieoff at all on a global scale which is what matters. Even during WWII, population increased, not decreased. Even during Mao's cultural revolution that supposedly saw tens of millions die, the global population increased.

The last time global population decreased was during the plagues of the medieval era.

You might consider WWII a collapse of sorts for some states in Europe but it was never a dieoff.

Ghawar Is Dying

The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function. - Dr. Albert Bartlett

I do not disagree with you, yet I still like to add some comments.

The jews might feel like it was.

The huge famines that Mao caused are called the "Great Leap Forward" and actually did cause a dent in population growth. Not for long though, and with small impact.

http://www.iiasa.ac.at/Research/LUC/ChinaFood/data/pop/pop_10.htm

Oddly enough that dieoff did not lead to a collaps of society.

Society was in a very low state of organization anyway during the plagues. Remember the feudal system? And even within the feudal system there were breakdowns of individual fiefdoms so you don't see any monolithic collapse because society was not monolithic, even though there was a nominal "king" of a region. In those fiefdoms was a high degree of independence of other fiefdoms. So the collapse of one did not affect the others around it too greatly other than to present an opportunity to expand their own fiefdoms.

The modern situation is far different with extreme specialization of labor, huge interdependences, etc. A massive fire in one memory chip factory in Asia back in the early 1990s caused global repercussions. At one point in time, a Wisconsin company made 80% of all hard disk read-write heads in the world. The global economy is far more fragile than you realize. There are not hundreds of memory chip manufacturers. There are not hundreds of aircraft builders. There are not hundreds of electrical transformer manufacturers. These manufacturing areas that I mention are so small yet so key to industrial civilization that they each represent near single points of failure and these areas are not alone.

One great danger to society is these very narrow areas of specialization coming up against economic collapse in the geographic region where these things are made. How do you restart the modern economy? Economists last year met and discussed this issue at a US government sponsored conference and concluded they had no idea how to restart it. This may be why Ben Bernanke, when faced with the choice between inflation and deflationary collapse has vowed to choose inflation?

Ghawar Is Dying

The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function. - Dr. Albert Bartlett

You lose me a little with the details, but I think what you are basically saying is that "discovery" of a finite resource creates an unsustainable boom. I'm not sure that is anything surprising or controversial.

You seem to be implying that economies without such a resource boom are better balanced. My question is, are those economies better off in the long run? In particular, if the UK had not built a booming financial sector what would have happened? Would our decline in maunfacturing have not happened? Would the capital investment have really gone into "less profitable" sectors, or just gone abroad? Would we have a better economy now and be a better country to live in if we had left North Sea oil and gas where it was?

The other point I would make is that there seems to be an assumption that smooth continuous growth is the "normal" case, and boom/bust cycles are abnormal - downturns caused by aberrant events. Of course, smooth growth is desirable, but in a complex system cyclical behaviour is inevitable. Although undesirable, the downturns are as much part of the normal behaviour of the system as downturns. The downturns needs to be considered as part of the overall system, and any system or model must also incorporate downturns, rather than treat them as exceptions.

Economists, or at least politicians, seem to have a view that if only they can tweak the system, they can have stable growth without downturns. This I think is misguided and probably futile. It would be like trying to adjust the weather to be always sunny and never rain.

Growth is not the norm within nature. In fact, nature demonstrates multi-million year periods of stability punctuated by what one might consider "violent" and aberrational cyclic behaviors. Therefore why should any rational human being believe that endless growth, either smoothly or in cycles, is the fate of mankind?

And if you don't like that, go argue with M. King Hubbert (amongst others). Physical scientists have long recognized that economics "has evolved from folkways of prehistoric origin" and is not a real science at all, neither applying the scientific method nor respecting its application in other sciences.

Politicians fail to control the economy because they are pursuing a myth, a legend. Economics is the global religion of the 20th century and will be the primary albatross that drags this civilization down. When or if we replace economics with a real science that deals with resources and finite boundaries, then and only then will we find a way out of the box canyon into which we have ridden.

Ghawar Is Dying

The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function. - Dr. Albert Bartlett

Eloquently stated, GreyZone. All discussion of economics amounts to rampant speculation. All one (we) can do is look at the real numbers (in joules) see what they spell out, estimate trends and prognosticate on how to mitigate declining purchasing power for per joule of work. Of course, on top of that, there can also be endless speculation as to geopolitical ramifications, social responses and the fate of man etc. Alas, I really do like when people say enjoy it while it lasts, because the majority of the people that run the world (aka the people with money and power) are strict adherents to the Church of Growth and the Oracle of Optimistic Economics.

...Pray to baby jebus that he spares us. That is all we can do, the rest is a giant maze built by followers of the great ape leader, Ponzi. Build a mirage in the jungle, you're in for trouble...

I disagree. Growth is the norm, but it is much slower growth than we humans are accustomed to associating with the concept. The 'growth' within nature can basically be measured by the increase in biomass on Planet Earth. I don't have figures on this and would welcome others' input, but I suspect Earthly biomass is still increasing, even though humans are skewing the ratio strongly toward human-centered biomass. Even if humans go the way of the Dodo (TWOTD) I think it likely that Earthly biomass will continue its slow growth. Even allowing for occasional wild fluctuations in warm periods and ice-ages, I suspect that the running average is upward.

Earth's biomass has been much larger than the present biomass many times in earth's history. Your assumption is incorrect as the biomass of earth dropped massively during extinction events and then exploded massively after extinction events. In fact, the regular state of the biosphere throughout geologic history is for far more dense biological activity than is current now, with aberrational events lowering and raising the overall biomass.

Growth is not the norm within the overall ecology. Long periods of stability are the norm. You are disagreeing with men as diverse as M. King Hubbert to Stephen Jay Gould. You are making an incredible and completely divergent claim from current biological science. If you are going to cling to this incredible claim, I suggest that you begin proving it. Otherwise you can stop disagreeing with those who have done the research and already reached data-backed conclusions vastly different from your own speculation.

Ghawar Is Dying

The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function. - Dr. Albert Bartlett

Don't get you knickers in a twist over my little speculation. I think it's safe to say at least that the Earth's biomass is vastly greater now than at the beginning of life. This is a truism. I'm not saying that biomass hasn't fluctuated, the issue is what the overall biomass curve looks like. Have you data on this? Or maybe I should just exercise my google key.

There are numerous academic papers that have some discussion of biomass density at various times. For instance, during the coal formation periods we either had forests with twice as much biomass as those today covering almost 3 times as much dry land surface as exists today or some variant thereof. The most likely case is dry land mass similar to today which leads to biomass densities during the carboniferous period of up to 6 times higher than those today.

Now, if you plot biomass over billions of years there is a clear upward curve but within the last 400 million years or so, there is mostly long plateaus near the top of the curve punctuated by events that suddenly lower (usually) or raise (much more rarely) total biomass temporarily. Also, if you plot total biomass, including that biomass sequestered by processes such as those that create coal or oil, then the biomass has been increasing steadily.

But in terms of biomass present at any given moment? Biomass has largely been on a plateau for millions of years.

Some references: http://www.pnas.org/cgi/reprint/97/23/12428.pdf

As estimated 90% of all known biomass (current and sequestered) was captured in trees: http://www.utoronto.ca/forest/termite/dec-lig.htm

Ghawar Is Dying

The greatest shortcoming of the human race is our inability to understand the exponential function. - Dr. Albert Bartlett

It's when you put all your eggs in one basket.

You get momentum built up into one specific area and orient your society towards that. If it goes, it is going to go hardcore.

Most real economists understand that growth cannot be infinite, the others have been sipping the koolaide. Noone wants the growth to end, cause the end will be bad, and not just really bad, but hell-on-earth bad.

If I get your idea straight, you believe that those countries which make large returns off financial services will suffer like the countries that made large returns off resources - on the conclusion of that 'bubble'.

Firstly, you haven't really demonstrated that the end of that bubble is coming. Yes, many here might agree that it will, but you ascribe the last 25 years to new IT and deregulation, so what's to stop there being some new reason for some new 25 years of growth? That case needs to be stronger.

Secondly, with the way the world works, finance is at the heart of our civilisation. If there is threat that reduces growth, etc. in finance, then it will also strike ever other industry and thus country. Doesn't matter if you have a country which has a healthy manufacturing base - it still suffers, perhaps worse since there is a fixed cost base in that situation, at least finance is virtual.

Lastly, the 'so what' question. You postulate that the finance edifice might fall, and that it might disproportionately strike the UK, US etc. - but what option for action is there? With the Dutch disease there is an implicit need for strategic diversification and preparation for a known problem and date. However thanks to point 2 above, that's not a winner with this concept, so.....what?

I'd suggest at heart what you are groping for is an alternative theory of non-growth economics. A way in which the growth/interest rate/inflation horsemen don't hold sway over civilisation. Understanding the parameters of that might give you some clues on this.

The bubble is bursting everywhere.

Remember that if you are in debt (the avg americans is in a ton of debt), you are exchanging FUTURE PROFITS for todays gain.

The explosion in credit is caused by an understanding that we are truely fucked. Everyone is taking short positions and hoping that debts to the future will be abolished, by way of a decreased standard of living.

The first to go will be oil age pensions. Those were established to allow a worker to profit in the future off his work in the past, implicitly suggesting that the future growth of the company would be enough to cover this cost. Same with the old age medicine and medicine in general. It is a stoploss, paid by the future.

really if old people make no contributions to the economy (beyond what they did in the past) why are they still being paid for it? There is a giant amount of older people hanging around and sucking the system. These will be the first to die-off, when you hear of old people having pensions removed, or getting screwed up the ass. Or generally complaining it is a symptom that growth is contracting. You are hoping to make money in the future, but know you can cut the pensions if you need to.

my advice to everyone is figure out your health care plan premiums, and pension costs. renegotiate your current pay for an additional 1/2 of those costs. You gain control, and the company saves a shitload of money.

Hi Jerome - an excellent post. Resource economics - a branch of neoclassical economics developed to reconcile sustainability concepts with neo-classical principles defines a sustainable state in many ways, but perhaps the simplest is one "where utility is non-declining through time". This goes to the heart of your point - "utility" (consumption) is going to decline for the reasons you give.

The problem that you rightly expose is that the natural resource base from which we derived out wealth, while it was there, is now going to be used up; and we will have squandered all that wealth - the UK for instance with the North Sea.

Hartwick said that in order for utility to be non-declining through time, that total capital should at least remain constant. Where non-renewable natural capital, such as oil and natural gas, is concerned, sufficient rent from the extraction of that resource should be invested in man made capital such that total capital, including natural capital and man made capital (know how and capital assets), remain constant. The principle is the same as maintaining a forest or fishery - to only live off the income it provides, not the capital itself.

In the case of oil this would have meant that sufficient of the profits from the UK oil industry were invested in alternative energy sources to abide by Hartwicks rule. This patently did not happen, but was consumed giving an illusion of greater wealth, even if it was for quite a long time.

What Hartwick had not identified was the destruction of other industries for the reasons you give. In other words Holland; and the UK shortly, is going to suffer doubly.

Of course Peak Oil is going to cook everything anyway, but this might provide some acedemic backgound for your treatise.

Resource economics deals with supply. Demand is where we need the work. Utility DOES NOT equal demand, we only think it does. Perhaps merging resource economics with buddhist economics might break some ground...

Hehe, only spoiled rich children think that utility equals demand.

A telling example of this theory is the Pacific

island nation of Nauru

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nauru

once rich in phosphate deposits. More lately they have been to running prison camps for Australia and money laundering for Russian mobsters. It was kinda embarrassing when the entire national airline was repossessed.

Rich countries were their best buddies when the phosphate was being mined but now they only have holes in the ground nobody wants to know them.

The Dutch disease was cured by the "Polder Model", a social contract between the government, the employers organisations, and trade unions. The name polder model refers to the ancient need to have a co-operative society in a country that is for the most part reclaimed land below sea level. Last week's text of the new European treaty has quietly removed language of open competition as the ultimate aim of the union. So, is it your opinion that, in Europe at least, some co-operative action is already in the works to try and cure the Anglo Disease?

Hi Jerome! Did you post this back home on ET? (You should.) or did I just miss it?

The the reason financial servives industry behaves like a non renewable resource sector is that their profits and performance came by making short term gains at the expense of future viability. Well, the future has arrived and the party is over.

However, it is a delight to see this translated into the language of economists, to blow the economists up with their own concepts.

Nicely put.

Hi Jerome

I have been worried about the manufacturing / finance ratio for many years now, even before I knew about peak oil.

What's been worrying me it the resilience of our economy if globalisation slips into reverse or if our trade with foreign partners falters for some reason.

As I understand it, in order to be a healthy wealth producing economy, you need both manufacturing and finance in your locality. It's OK for individuals to specialise. When the whole country specialises lets it manufacturing disappear overseas and wither, the whole country is specialising and then becomes more dependent on trade (and easier to charge higher prices to).

The same paradigm applies to food and energy creation. If you don't keep your non-substitutable parts of the economy then you are having to trade whatever the global circumstances.

Now peak oil and expensive transport just brings it into sharp relief exactly how exposed we are in the UK to having to trade for survival.

Carbon - Coventry, UK (the british Motown as was)

Would it be a fair conjecture that manufacturing is far more liquid that ever before? That is, there is now knowledge and method to go in anywhere that basic infrastructure exists, quickly build factories, and quickly and adequately staff those factories. The prime example: Look at how fast China has been filled with factories; largely by the Taiwanese, who had practiced at home and in smaller Asian nations as preamble, but also by Japanese and Americans.

With this being the case, industrialization - meaning being well-stocked with factories - doesn't count for so much as it used to. Machines are now smarter, so far less training, on average, is required to run them. Transportation is nearly universal, and communications are universal and instantaneous. If there should be an advantage in restocking the UK or the US with factories, that can be done, for most industries, in a 3-to-5 year window.

Transport to the UK and to the US coasts will never be expensive, though, for any goods which aren't perishable. Freighters can use modern sail designs to cross the oceans with minimal use of fuel. When fuel gets dear enough, they will be built. The engineering designs are already advanced. So the advantage to siting factories in Asia will continue for a few decades, even given an early occurrence of peak oil.

How much have the returns on financial services been precisely because such services are required for the fluid placement of manufacturing capability in a globalized world? That is, are the banks taking a large share of their profit from the advantage in manufacturing costs when factories are moved to Asia and particularly China?

While the Chinese certainly have the cash to become bankers in our place, how long will it be before the world will trust a Chinese banker? My guess is we're some decades out on that, too.

And who wants to borrow money in a contracting economy?

And who wants to lend money in a contracting economy?

As Will Rogers said, "It's not the return on my money I'm interested in, it's the return of my money."

You miss the whole point of the oil peak. Sure, information can move around, by snail mail if need be, BUT it takes energy to build the factories where you want at a whim. How many earth-movers and cranes are going to run if diesel costs $20/gallon? How many FedEx flights will go if the jet fuel costs the $20/gallon? How many business trips will a kingpin go on if the jet fuel is exhorbitant like that? And that's assuming there is the fuel there in the first place. While jets will burn anything flammable (continuous burn) the piston engines are picky petrovores like toddlers.

Very high fuel prices makes building new factories very costly quick. Even with "universal machines" you still need energy to make them, just like building factories. Too far past PO, factories get stranded. The shipping costs even with crewless computer-guided ships, the fuel costs raise the price of the shipped goods toward unaffordable. Low value-added product will be hurt first like bulk grain. Later, the fuel cost works up the food chain.

We can see that principle with the escalating of the "drug war". As law enforcement is escalated, the risk of bust increases. Thus, drug smugglers look to smuggle higher value-added product. First marijuana, then cocaine, to heroin (pure) and getting into fentanyl-laced heroin. The ultimate conclusion is to make heroin into wildnil - an even stronger drug than fentanyl - to smuggle. Given GPS and old laptops, it's almost a miracle smugglers don't yet launch unmanned self-driving go-fast boats.

As time goes by, the price of the stuff at Wal-Mart will climb as fuel cost climbs. The markup will be little on an iPod (but fabrication cost will climb!) but be easy to see on kids' shoes.

Petrol prices high enough yet? Just wait!

The dramatic decline in the UK manufacturing base started in the mid seventies, perhaps not coincidentally, at the same time as we started to produce and export North Sea Oil.

Most economic commentators that I have read in the UK have complained that the pound has been overvalued since at least the time of Margaret Thatcher, while in contrast the history of the pound for most of the period from the end of the first world war until the mid-seventies was one of continuous balance of payments crises and devaluation.

Would it not be more reasonable to postulate that the UK has simply had thirty years of continuous Dutch disease.

Because we could export lots of oil, we could pay for our imports without exporting very much else. The pound became overvalued, so basic manufacturing became uncompetitive, and industry declined.

Britain in this regard would seem to share, to a lesser extent, the fate of producer countries as diverse as KSR and Nigeria, where high costs make labour intesive industries uncompetitive.

In the UK we were fortuante that into this space stepped financial and other services, which currently provide near full employment.

Although we have recently become an oil exporter again, the pound is still overvalued, but at the moment this is due to a shorter term but very big housing bubble, which appears to be finally beginning to crash (though both France and Spain demonstrate that financial excess in housing is hardly a uniquely anglo disease).

Once the bubble has been pricked, interest rates and so the exchange rate will drop, and the UK might start increasing manufacturing exports again.

Oddly enough, detailed examination suggests that with one crucial exception the UK and French economies are remarkably similar. France has major international banks, as well as service companies such as Carrefour. The UK has near record levels of car production, though we wisely leave the management of these companies to the Japanese, Germans and the French.

The only big difference between the UK and French economies is down to employment and productivity. The UK has very flexible employment policies that allow the creation of many low paid jobs, and also allows relatively low levels of productivity. France has chosen very high levels of employment protection, which is very good for those poorer French people who have a job, though less good for those that do not. A consequence of the very high costs of employing people in France is very high productivity, it is easier for a French company to employ a machine than a human being.

It would be presumptious of me to claim which is the better model, but in the last few weeks a majority of the French electorate have made some pretty clear statements of the direction they wish to go.

Smaller countries such as Holland, Switzerland, Finland and Sweden have managed to move to a post industrial future while avoiding the turmoil of the UK, possibly a useful model for all the larger countries? For the UK to temper the worse effects of free market capitalism, for France, Germany and Italy, how to successfully move on from a religious position that holds that manufacturing is the source of all wealth.

Jerome

Fine article. I am with you with all that you write in it.

The global financial world has evolved into a gigantic gambling casino with hallucinated welth. Surely this is not sustainable, and will at some point burst perhaps along with the global fiat currency system.

Then comes PO upon this. We are ceartainly in uncharted waters. I am not the man to forsee the outcome, but personally i have all my savings in gold and silver, and nothing in any kind of paper certifikates.

Kenneth

Jerome, as far as the UK is concerned you have described

the situation very accurately.

As a retired banker I have always considered that the

discovery of North Sea oil and gas was a disaster for this

country, as it enabled us to avoid making necessary structural reforms to our decaying industries, and to

continue living well beyond our means.

Also our new found wealth has attracted vast numbers of

economic migrants. The income from the North Sea bonanza

has been largely frittered away, and the oil and gas will be

"effectively all over by 2020" (Per UK Department of Trade

and Industry website). We will then be almost totally

dependent on selling financial services, and despite

propaganda to the contrary, it is relatively easy for other

countries to compete for this business.

By that time the UK will have to try and support a population probably approaching 70 million, in a World

facing shortages of food and other critical resources.

IMO the situation here has the potential to become somewhat

ugly.

Mr Toad, I too fear greatly for the UK and yes, Jerome, like the boy in the story has identified that the Emperor wears no clothes.

Even if we stayed competitive in the selling of financial services, there is no reason to believe that individuals, corporations or countries will require these services. And anyway, back room activities are already offshore.

What then can we trade for foodstuffs or oil? - Though again, that assumes that even if we had tradable goods that oil and foodstuffs would be available. This looks increasingly doubtful. Not a lot to trade then and in a world where global trading is simultaneously hit badly by energy and food constraints.

So, we will be pretty much on our own with a population of 60-70 million and no way to feed it. Even ID card - based rationing would struggle to feed the population, and no surplus cash, energy or manufacturing base to re-engineer infrastructure projects or any way out.

This is the problem: (England and Wales)

Year Population Year Population

1348 5,500000 1811 10,165000

1375 2,750000 1821 12,000000

1450 2,400000 1831 13,900000

1500 3,200000 1841 15,900000

1570 4,160000 1851 17,900000

1600 4,810000 1861 20,606000

1630 5,600000 1871 22,712000

1670 5,573000 1881 25,974000

1700 6,000000 1891 29,000000

1750 7,000000 1901 32,527000

An agrarian (and fossil fuel free) population of perhaps 10 - 20 million in the UK.

Assuming flooding due to global warming doesn’t drown productive farmland.

So, if we have the Anglo disease, what then is the cure?

Is there a cure?

Indeed - ignoring everything else, the UK is going to need to be importing an additional net 1 million barrels of oil per day in a few years time. Where is this brand new 1 million barrels per day going to come from next decade? We talk a lot about the increasing local consumption of oil exporters reducing their exports, well the UK's North Sea decline will manifest itself as increased demand on the market.

Will that demand be met with correspondingly increased exports from an existing exporter? Hard to see where.

Will it be met at the expense of current importers, poorer than the UK, being out bid? Maybe, but it assumes the UK has more foreign exchange than the next country.

Or will that shortfall simply not be met? 5 years from now the UK will be using less oil than today.

If we use a 5% decline rate for the top five net exporters and a 5% rate of increase in consumption, I estimate that their net exports will be down by about by about 10 mbpd--about 40%--in five years.

We will find it increasingly hard to bid for the shortfall in oil imports.

Oil imports at these prices act as a Tax and brake on the Economy. Cost of goods such as cost increase in food also act as a Tax brake. The inflation then caused is fought of in conventional economics with interest rate rises also acting as another Tax brake on disposable income.

Less money, less access to energy, and increasingly less access to develop alternatives to gas fired power stations.

Less industry, lay offs and then casting around for scape goats.

Westexas' export land model appears to be as powerful a force in the universe as compound interest...

Now is not a good time to for the soon to be formerly middle class.

Or a politician: It is always an angry articulate middle class that agitates for revolutionary change. (see Revolutionary France, Weimar, AWI).

No wonder the BNP are sitting back and licking their chops.

They just need to do nothing and wait. PO+ELM will land the UK population in their lap.

I thought we may have had a few years grace yet, but PO + ELM look like the jaws of an inescapable vice.

Ah well, bang goes retirement then.

British industry has been in decline as long as most people can remember. It was already in a bad enough state for asset stripping speculators to move in in the 1970s and Thatcher's brief love affair with monetarism-inspired high interest rates in 1979-80 helped destroy a lot of what was left. Venturing into personal opinion now, but I believe that the destruction of the worker protection and the unions consigned Britain to a future without skilled blue-collar employment.

The Thatcher/Reagan years definitely helped create a something-for-nothing culture and I believe this is an Anglo phenomenon distinct from say old Europe. In Britain, aside from the "big bang" financial deregulation, such thinking was allowed to pervade throughout British society with public housing and national utilities being sold off for fractions of their real value. I think it is no coincidence at all that the Anglo countries, OZ/NZ included, have seen the greatest housing bubbles in recent years.

One of the big financial magazines recently described London as a virtual tax haven. It goes without saying that this greatly limits the benefits of such economic activity to society as a whole.

For self-sufficiency, what Britain needs is land seizures. That's a dramatic option, but the truth is that a couple of hundred old families still own the majority of the country and are subsidized to the hilt for doing so. See "Who Owns Britain?" by Kevin Cahill.

I'm not quite sure I agree with your cart and horse statement about the long term decline of inflation and thus of interest rates. It is fashionable to make this link, but I am not convinced that inflation has been held in check in the period stated. Like the reality of resource depletion, it has merely, and cleverly, been made to appear to be in check while the fundamental reality continues.

My personal view is that we have been trying to print our way out of a situation in which the manufacturing capability as well as the energy capability has been slipping from our hands. Low foreign wages, ownership of the current trading associations, and control of the currency that energy has been denominated in, plus an overwhelming but increasingly irrelevant military domination has allowed the fantasy to continue.

I agree with your premise, but the inflationary aspect depends mightily upon what is currently a fashionable definition and methodology which your treatise seems to be in itself undermining. Inflation isn't wage demands or goods prices but the creation of money above and beyond the scope of the economic activity which it relates to. A deflationary recession doesn't destroy that money but merely reduces its velocity. As the FSU discovered after the realignment, the vast amounts of money in savings with no goods to buy suddenly had the prospect of velocity.

China has been a huge influence upon inflation, at once inflating the incomes of the traders and deflating those of the workers. If neoliberalism means removing the bargaining rights of workers in a race to the bottom, it appears to be just about to succeed in shooting itself in the foot. At once invisibly deflationary and inflationary - you can't see it if it averages out and therefore doesn't exist - it is vunerable to one or the other becoming precipitately dominant with no simple redress.

In a way, this was what happened in the 70's when inflation by outside forces managed to get us to the dime is a dollar point before being stopped by high interest rates. At least that is the official story. I would submit that the actual remedy was the development of energy alternatives to OPEC and that the rates and recession merely drove the point home to speculators. Attempts to print our way out of an energy shortfall were as fruitless then as they are now, but the insistence that global labor costs be tallied to measure domestic inflation still has credibility. While I accept the official fiction as a good story, I would hope that other government departments wouldn't base policy upon it.

No doubt they will. And of course the accumulation of outsized and unseviceable debts will never be held accountable. What? Mea culpa?

Very interesting article.

One thing that has struck me about the financial industry is its reliance on models that assume infinite growth - continued expansion - no resource limits. Once we hit resource limits, those models fall apart, and I think the financial sector hits the wall. There is no way long term loans of any sort (home mortgage, business, governmental) continue to make sense, once a person understands that the future will be worse than the present, not better. The Anglo Disease model helps understand what happens when the finance sector hits the wall.

I have written about the way the finance sector assumes infinite growth a couple of different places. One of these is Our World Is Finite: Is This a Problem?. Another is Our Finite World: Implications for Actuaries. The latter is an article aimed at actuaries in Contingencies magazine, published by the American Academy of Actuaries.

Your post echoes mine in a different way. Those inflationary house prices assume a functional and non contracting economy to service the debt. Contracting economies encounter a debt service problem, and our current debt load assumes an expanding and/or inflating economy. Given the oil situation, the only remedy is a crash course of alternative energy investment which I don't see happening, yet. It also assumes that this investment be energy productive rather than a mere make work.

Good articles, Jerome and Gail.

Jerome, regarding the liquidity that you rightly point out is drying up (to the coming detriment of the financial industry)--isn't liquidity just another form of oil?

Even in a zero-growth, steady state economy, assets (including money) must have a rental value. Otherwise, they would be "free", resulting in waste and inefficiency -- just what you most want to avoid in a steady state economy. Those rents constitute the space where financial services can continue to operate. It is a considerably more confined space than that to which they are presently accustomed.

Measured from the absolute peak in 1980 to the absolute low in 1999, WTI oil prices fell, in nominal terms, from about $40 per barrel to about $10 per barrel, with lots of fluctuations along the way, but always below the 1980 nominal peak.

I suspect that this long term oil price decline was a contributing factor to lower interest rates. It certainly contributed to faster economic growth. This economic growth was further aided by the technological revolution, which allowed many poorer countries to start industrializing, and to begin turning out low cost goods at a very high rate, which contributed to the shifting of manufacturing to overseas companies.

All of this was based on the expectation of continued low energy prices, and most importantly on the expectation of an exponential rate of increase in exported crude oil and petroleum products, the very lifeblood of the world industrial economy.

If this expectation of an infinite rate of increase in the consumption of a finite energy resource base were justified, our economic system would actually make some degree of sense (leaving aside the climate change issue).

Unfortunately, common sense, our mathematical models, and recent data suggest that it will not be possible to experience an infinite rate of increase in the consumption of a finite energy resource base.

And as I have repeatedly warned since January, 2006, the developing problem is net petroleum (crude oil + product) exports.

From 2005 to 2006, the top five net exporters showed a 3.3% decline (the top four were close to 5%) in net exports (EIA, Total Liquids). From 2005 to 2006, the top five net exporters showed a 5.5% increase in consumption. In 2006, the top five net exporters accounted for half of worldwide net exports.

If we assume a 5% decline rate in production by the top five and a 5% rate of increase in consumption, their collective net exports would be around zero by about 2020.

In my opinion, the lifeblood of the world industrial economy is draining away in front of our very eyes.