Where Does the US Import Oil and Other Petroleum Products From?

Posted by Gail the Actuary on October 19, 2008 - 11:50am

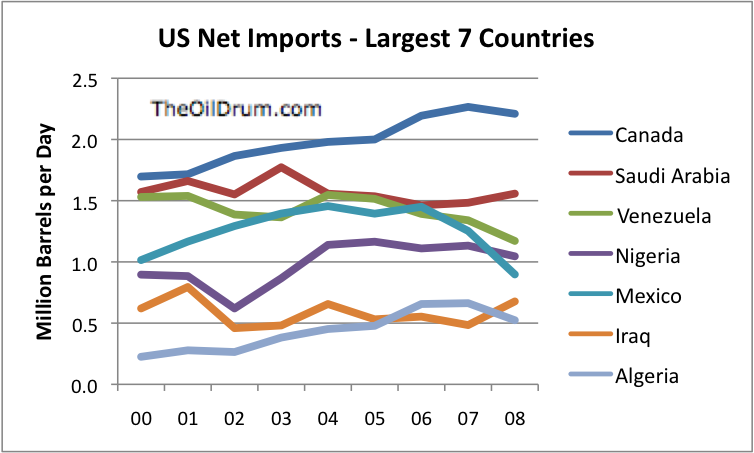

We all know that the United States is an importer of petroleum products. The United States is also an exporter of petroleum products, primarily to Mexico and Canada. Both of these countries send us crude oil, and we export refined products back to them. We often hear that Canada and Mexico are our largest sources of petroleum product imports, but is this really true if we net out exports? Canada remains number 1 when we net out exports, but Mexico drops to fifth place in 2008. (Mexico drops to third place in 2008, without netting out exports, because of its declining volume.)

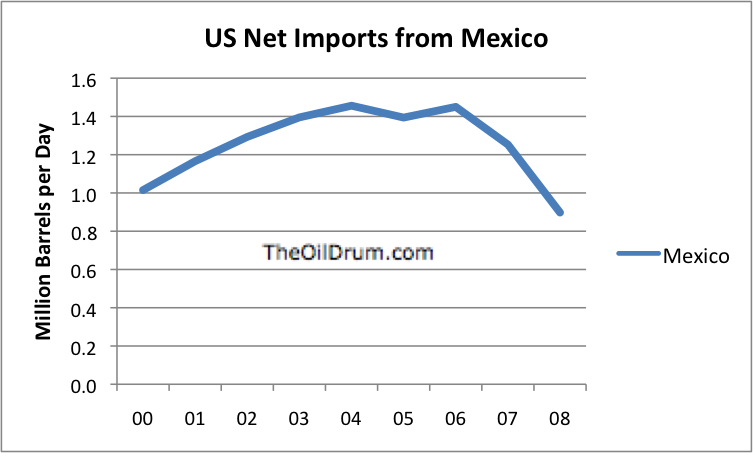

The graph in Figure 1 is sort of "messy" with so many lines in it. If we look at US net imports from Mexico alone, this is the pattern we see.

We can see from this the rapid decline in imports from Mexico (exports from Mexico's perspective) that we have been hearing about. The 2008 value is the actual calculated value of 898,000 barrels per day through July (1,302,000 imports minus 405,000 exports), rather than a projected value at year end. If production continues to drop, it is likely to be lower at the end of the year than through July.

Looking back at Figure 1, there are several things that are interesting:

1. Net imports from Canada haven't been rising very quickly. Net imports for 2008 YTD are in fact down about 2.5% from the 2007 value.

2. In order, our largest sources of net imports in 2008 are Canada, Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, Nigeria, Mexico, Iraq and Algeria.

3. Except for Canada and Mexico, all of the countries on the list are members of OPEC.

Looking at the EIA data underlying the graph, the next two smaller countries in terms of net imports are Angola and Russia. Clearly a substantial majority of our net imports come from OPEC or Russia. At one time, we were importing oil from Norway and Great Britain, but this is rapidly declining with the decline of oil from the North Sea.

Figure 3 shows a graph of total US oil and petroleum product imports, both on an "imports not considering exports" basis, and on a net imports basis.

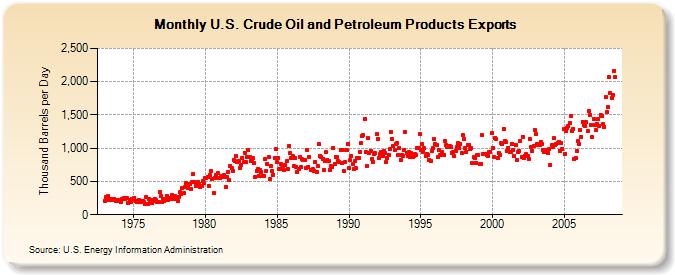

We have been exporting more refined products in recent years, with the big recipients being Mexico and Canada. For all countries combined, this is the EIA graph of US petroleum products exports.

Our biggest exports to Canada in 2007 were residual fuel oil, 32,000 bpd; crude oil, 27,000 bpd; and coke, 23,000 bpd. To Mexico, our biggest exports in 2007 were gasoline, 101,000 bpd; coke, 47,000 bpd; and distillate, 34,000 bpd. Of these, residual fuel oil and coke are byproducts that we have an excess amount of. Coke is used as a substitute for coal.

Clearly, exports have been growing rapidly. A few years ago, one could make the argument that exports were immaterial, and could be ignored. It seems to me that one needs to consider the combination of imports and exports in analyses today.

Robert Rapier wrote related post in April 2008 called US Oil and Gasoline Import Statistics.

Hi TODers!

With diminishing oil exports from up north and down south, i have fallen out of love with petroleum all together- check out my video on this subject: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8ujaEca_Dcg

If you want to cut that tree down, Kris, you have to keep hitting the same spot with the axe :)

Somebody needs to get a job ...

Wonderful, wonderful video, Kris!

I have friends and family who are afraid of the peak oil topic who will actually watch this video! Much thanks to you for this and the many creative videos you've made along the way. Great work!

Thanks for another informative post, Gail. It's interesting that this, a technical post, gets few comments while the less-TOD-centric posts get a ton. :)

Doesn't this view, from an import perspective, lend an awful lot of credence to WT's ELM, or maybe more specifically NELM (net export land model)?

This data says we're already well past peak from an import perspective. If you add in local production, does the curve still trend downwards from 2005 or so as well?

If the overall US net oil trend is down, it means the financial crisis probably isn't a monetary black swan, but an everyday fledgling from the peak oil nest.

Total Imports seem to be Down about the same amount that Biofuels Production is Up. A "touch" more, but close.

Do you even understand the ramifications of what you just wrote in light of all the facts of biofuel ERoEI?

Do you understand that E85 is selling in Iowa for less than $1.70/gallon?

Or that biofuel eroei is getting better, while petroleum eroei is getting worse?

We don't KNOW that petroleum EROI is getting worse but we can assume it.

Assume it has declined from last analysis (Cleveland, Hall 2001) from 10-17:1 down to 8:1.

Assume that corn ethanol has increased from 1.3:1 to 1.5:1 (though ethanol requires that DDG get an co-product credit otherwise EROI drops to near parity).

So the energy gain on oil is 8:1-1= 700%, while the energy gain on corn ethanol is 1.5:1-1 =50%. There is at least 14 times more energy surplus per unit on oil than corn ethanol, possibly much more.

But that's not even the point. There are two other critical issues: 1)this society was built on cheap oil, implying high energy return oil. IF oil does decline to 5:1, or 3:1, etc. and biofuels DO increase to say 2:1 or 3:1, we have a huge problem (and this might be happening now - look at all the oil projects being scrapped due to low prices!) Then ALL society would have less energy surplus, which manifests in the real economy via prices. If this trajectory occurs, oil would be $1000 per barrel or some equivalent number that would make modern society unable to function.

Secondly, you ignore all the environmental externalities. Oil production requires less land, less environmental footprint, 2 orders of magnitude less water, and less contamination of drinking water, less soil erosion, etc. (Here is a summary of a National Academy of Science report on the externalities of biofuel production. I'm no fan of basing our future on oil, but basing it on biofuels is jumping from the frying pan right into the fire.

Using biofuels for local communities - GOOD IDEA, where appropriate and they don't eat into other limiting inputs. Scaling biofuels nationally or internationally as a replacement for liquid fuels, TERRIBLE IDEA, with myriad unintended consequences, all of which you know, because you have been promoting ethanol here for years, and Robert and I (and others) have been responding to you for years. The most interesting question I glean from your post is why do I continue to respond to them? I guess it's in case there are others who still don't know the wide boundary problems with large scale biofuels.

For "Years?"

I take that back. You have only been a member for 36 weeks. But there are other posters in the ethanol business that have been posting here for years..Sorry for that mistake.

And, I'm, also, NOT in the "Ethanol Business."

0 - 2

'Sides, I'm better lookin than them other guys. :)

Nate, our water usage for ethanol in the U.S. is only 2.75% that of the water used for "Golf Courses."

9700 USGA courses. One golf course = one 40 Million gal/yr ethanol refinery.

You have to separate betweeen water withdrawals and water consumed. Also, ethanol refineries are much more local while golf courses are spread out.

But I gave up golf for that reason (well, I kind of sucked too).

It's not all about how much water you use, but what happens after you use it.

A golf course grows grass that takes CO2 out of the atmosphere which helps reduce the green house gas problem.

The ethanol refinery - well, here is my personal contact with that.

They built a new refinery about 8 miles from my farm. They were going to dump all their waste water into a creek that just happens to be part of a major State Park downstream of the ethanol refinery. Enough people raised hell and made the State EPA withdraw their permission to pollute the creek, so they gave them permission to build a pipe line 6-8 miles cross country so they could dump all of their waste water into the Minnesota River about a mile upstream of my farm! Please note that the State Government has "been working hard to clean up the Minnesota River" which is one of the most polluted in the State of Minnesota and maybe the USA. Hell of a good way to cleanup the River - just dump all the ethanol refinery waste into it. Boy oh boy, does money talk!

That's interesting, Jon. Just what is in that water that makes in so environmentally bad? This is Not a "snark," or a "trick" question. I'm, sincerely, interested in what it is that Minnesota does not consider polluted that we might.

Assuming it's untreated sewage, it's likely full of organic matter. Organic matter rots and removes oxygen from the water, creating dead zones. Organic matter also fertilizes water, helping to create algal blooms.

Golf courses do nothing to help with respect to global warming. Any grass that grows (and plenty does with the amount of fertilizer used) is cut within weeks and the carbon released soon after. Golf courses themselves are very energy intensive on a per-customer basis and they use up huge amounts of city or suburban land, causing more sprawl and all the ills associated with it.

As far as the ethanol mill dumping untreated sewage, it doesn't surprise me considering how political in nature the industry is. Politicians support it because of special interests, not because of any real environmental benefit. Those special interests (the farm lobby) are looking out for number 1, not for the environment.

"Dilution is the solution for pollution" :-) Limerick at least as old as the Clean Water Act.

I'm confident that that number is only for ethyl alcohol refining and not for growing the feedstock. Using irrigated land, it easily takes 10,000 litres of water to make 1 litre of corn-based ethyl alcohol.

Nate,

R^2 on his post threw out a number of .52 gallons of water per gallon of crude for refineries.

Yet NREL gives 2-2.5 gallons of water per gallon of gasoline versus 3-4 gallons of water per gallon of ethanol(which does agree with the 3.5 given by your article. Cellulosic could be 1.9- 6 gal of water per gal of ethanol.

You also seem to exaggerate the issue of corn irrigation--afterall 96% of the crop is NOT irrigated.

http://tiny.cc/s8blY

The advantage of ethanol is that it doesn't require much oil to make it. 1 gallon of ethanol replaces 7 gallons of petroleum per Shapouri. It's just not an EROEI issue at this point( adding even 10% ethanol to fuel marginally effects mpg).

http://www.ethanol-gec.org/corn_eth.htm

The problem is the scale of our use of oil.

Ethanol isn't a TERRIBLE IDEA, but it is a limited idea, IMO.

I'm sympathetic to people who want to limit the environmental effects of massive ethanol but it's certainly practical.

I've got to agree with the general direction of your comment, Majorian. I would be much less sanguine about our energy future if it wasn't for hybrids, plug-in hybrids, EVs, Nuclear, electrified rail, wind, geothermal, etc.

There are just scads of opportunities available to us. California's going to hit their 25% renewable target in a breeze. Without even a "drop" of perspiration.

Combine all the new technologies in ICE's, biology, solar, etc. it just looks easy from where I sit. We knock the "Need" for liquid fuels down to 5, or 6 mbpd, and ethanol/biodiesel/biobutanol, etc knocks it right on out. Easy.

R^2 on his post threw out a number of .52 gallons of water per gallon of crude for refineries.

I didn't just "throw out" that number. First, I worked at that refinery and know exactly how much water we used. But second - I used the publicly available water bill from the city of Billings. So, pretty tough to dispute that number. You may not want to believe it, but it is what it is:

http://i-r-squared.blogspot.com/2007/03/water-usage-in-oil-refinery.html

You sometimes see numbers that are much higher. For instance, I have seen high numbers for BP's Whiting refinery in Indiana that uses lake water for cooling. But what you will find is that the water only passes through the refinery and doesn't contact the process. They pull water in from the lake, use it to cool the process, and put it back in the lake a little warmer than they took it out. The more water they pull, the less temperature rise. So the more water they use, the less impact on the lake.

1 gallon of ethanol replaces 7 gallons of petroleum per Shapouri.

1 gallon of ethanol plus corn plus natural gas plus coal.

Come on, RR. You know that 7 gal. is an Ooooold number. You know it's down around three, now.

Read for comprehension. Or do you want to stand by your implication that a gallon of ethanol displaces 3 gallons of oil, and not 7 as Majorian asserted?

Mea Culpa, Big Guy. I'm an asshole.

Gonna go take a nap, now.

And, besides, you act like oil refineries don't use any natural gas.

And, besides, you act like oil refineries don't use any natural gas.

Do I? Where do I act like this?

My former refinery used lots of natural gas. It was a by-product of the refining process. Sometimes we would also buy natural gas if it was more economically attractive to do so. (You can run a refinery to produce more or less natural gas, depending on what is economically attractive). But we were certainly capable of running the refinery from the fuel gas we produced.

No more replies from me. I am in Europe and it is bed time.

Okay, one last thing. The avg. refinery responding used 3.45. The newer ones, 2.65 gallons of water per gallon of ethanol.

http://www.ethanolrfa.org/objects/documents/1652/2007_analysis_of_the_ef...

Rome fiddles while Nero burns?

Okay, .52 gals of fresh water per gallon for the Billings refinery.

That made me think that Nate was talking about sucking the nation dry to make ethanol so I posted the 2-2.5 gallons of water per gallon of gasoline from NREL, who I also don't accuse of 'lying'; maybe that number is total(recycled) gallons rather than fresh water.

At any rate, it appears to me that ethanol is roughly comparable to gasoline in water usage.

We are also talking about a 'bridge' program for the next 50 years and 'energy independence' and we have lots of coal for that(practically speaking).

It would be nice if we could verify the NG given that the country is apparently signing on with T Boone Pickins.

I have always said that corn ethanol is a bridge to cellulosic ethanol and is justified as an oxygenate to replace MTBE under the current EPA rules. It will max out at 15 billion gallons by law. IF the country uses half the gasoline it does now, E85

will be justified IMO.

That's the real challenge.

96% is an upper limit, as your source states.

I agree with your basic point that irrigated corn acreage is a small fraction, and your most important point, that etoh will never scale, a bad idea.

Based on the 2002 Farm and Ranch Survey, irrigated corn for grain accounted for approximately 571,140 thousand bushels, compared to a total crop of over 8,613,115 thousand bushels, a little over 6 and a half percent. When looking at that survey from an area perspective, we find about 14 per cent of the corn cropland was irrigated in some form.

Based in part on the methodology and questions of the survey, it is subject to error, but it is by far the best data we have. Interpretations can be made for full vs partial season irrigation, among others. The 2007 survey was mailed last winter, and should be out soon. I expect irrigation percentages for corn to rise, perhaps dramatically.

Ok, so if you can run 700 delivery trucks on the oil EROEI, you can run only 50 on corn ethanol, based on 8:1 for oil and 1.5:1 for corn ethanol. I think your assertion that we have a huge problem might be a slight understatement.

Looks to me like many of us are closer to death than birth, and that is not necessarily based on advanced age.

Henry, do you have the nagging feeling looking at that post that something's wrong with it? Sure you do. Here's the problem.

You take 130 some odd thousand btus of crude oil, burn another ten, or twenty thousand, or whatever of nat gas to turn it into 116,000 of gasoline, and, proudly proclaim: "Voila, 8:1 eroei.

On the other hand, farmer joe takes a thousand btus of diesel, thirty three (or, often, less) btus of nat gas, reaches up in the sky and grabs a little solar energy, produces 76,000 btus of ethanol (with a 115 Octane rating, by the way) and you proclaim: 1.5:1 eroei. Doesn't make much sense, does it?

Sometimes, you just have to go with common sense. Ethanol costs less, even without tax credits, for a reason.

Well, if we cannot solve our coming liquid fuels problem quickly (meaning changes in land use and urban design to increase non-SOV transportation - bikes, walking, mass transit, car pooling, etc. plus increasing the use of rail for long distance shipping) we will need bio-fuels, no matter HOW BAD THEY ARE.

And the reality may be that as a population the American people may actually choose fuel for their car over food. I mean this in aggregate.

It takes energy and water to make biofuel.

Both of which is in decline.

So you are saying we need to ramp up the use of these declining essential commodities for fuel?

Souperman,

as for "water," see my post above. As for "Land." Soup, we used to farm 400 million acres in the U.S. Today, we're rowcropping about 250 Million. Heck, we're paying farmers Not to plant 34 Million acres.

Corn yields have increased 67% since 1980, and fertilizer use has declined 10%. The Stanford study found, at least, One Billion Acres of Abandoned farmland world-wide. The new Sorghum seeds negate the aluminum toxicity found in 50% of the world's arable land. They figure they'll do the same with corn in just a couple of years.

Besides, we're beating a "dead horse," here. We're, almost, 70% of the way to the max corn ethanol we're going to produce. From here on out we're looking at Municipal Solid Waste, Flue Gas, Forest, and Agricultural Waste (Poet figures we can do 5 Billion gpy just on corn cobs,) sugar cane, sweet sorghum, switch grass, etc.

As for "energy:" The old U.N. number was 8 gal of diesel to farm an acre of corn. It's gotten better with no-till, low-till farming. (I seem to remember X stating that he used about 5, or 6 gallons of diesel/acre.)

If you deduct out the distillers grains you're looking at about 700 gallons of ethanol per acre. Now, we're currently using between 23,000 btus, and 35,000 btus of natural gas for refining, and fertilizer; but those numbers are coming down, and will in the future come down greatly. Again, the cellulosic plants (msw, etc) will pretty much supply their own process energy.

In other words; the whole idea is that ethanol/biodiesel production is "energy positive," thus "energy" is not a "bug."

I guess I'm saying the "market" as an aggregate may choose to pay a lot more for food and will accept environmental damage to keep the cars rolling, yes.

I think that is terrible, but that is the way of addiction, is it not?

I am not optimistic that the majority of Americans will one day wake up to the wisdom of re-localization and walk away from a petroleum-dependent life style. Yes, one can point to upticks in transit ridership and faster drops in home values in outer suburbs, but is that moving fast enough? I doubt it.

And municipalities are having trouble maintaining transit funding due to our financial crisis.

Americans are so far behind the curve on this.

But the Saudis, and other OPEC members as well as Russia, certainly are not. Kevin Phillips calls the U.S. response the "politics of evasion." It seems like Amricans will be the last ones to wake up to what has been evident to the rest of the world for some time. As Phillips put it:

You think we're in trouble. Take a hard look at Europe. They're "locked into" Diesel, and have very limited oilseed capacity.

Plus, they have, already, cut the size of their automobile engines about as far as they can go, and have very little "low-hanging fruit" left.

Eh?

Europe is a small place. I can practically WALK across the continent in a few days ... OK, maybe not, but you get my drift ...

We now have small, efficient cars with relatively short distances to travel.

Many European countries also have fantastic public transport.

We are NOT 'locked in' ... we are close to being ready for expensive, rare fuel.

We also have alternatives to using the car.

Sounds good to me.

Okay, I'll take your word for it. Obviously, Madrid is a Looooong way from Mississip.

Thanks Gail for putting together these numbers. It's not what I expected. One could argue that the US has some 'power' in that we export refined product to countries that have few refineries but that is small consolation. I suspect when Mexico stops exporting is when these issues will finally break loose into the mainstream. Has PEMEX even acknowledged that as a possibility? Or are they 'cost-blind' like the other governments/oil PR firms?

Doesn't this hasten WT's net export breakeven point for Mexico, if our exports to them fall more slowly than theirs to us?

This is pretty much consistent with WT's Mexico's net exports, as far as I can tell.

When he looks at their consumption, the consumption includes the petroleum products that we have exported back to Mexico. What is not consistent with WT's model is an approach which takes a one-sided view of the petroleum the US imports from Mexico, without looking at whether it goes back to Mexico.

Somehow the oil has to get refined, and it doesn't matter whether it is in the US or Mexico.

As I have said before, the implications of WT's ELM analysis are that sooner or later (and probably sooner than most people realize), the US (or North America, at least) WILL become "energy independent". This won't be due to some brilliant plan on the part of our government, regardless of the individuals elected. And please note, unless several very drastic changes start immediately, it won't be due to our ramping up domestic energy resources to the point where we can maintain BAU.

The US will have to learn to live on considerably less energy, and FAR LESS oil, than we are now, and soon. The sooner that everyone faces up to that sobering reality and starts adjusting to it, the better.

I suggest as a very rough guideline for planning purposes to think in terms of the US having to operate on about 1/3 of the conventional oil that it is presently by, say the early 2020s or so. Maybe with any luck we can ramp up production of tar sands, biofuels, CTL, etc. to bring "total liquids" available to us up to 1/2 of what we use at present, but I think that is being extremely optimistic. We might be so lucky as to stretch things out to where we might not actually reach this point until as late as 2030, but again that is being very optimistic. There are a lot more things that can go wrong in such a scenario than there are things that can go unexpectedly right.

When the US has that little liquid fuel at its disposal, I believe that we can take it for granted that the government will do whatever it needs to do to assure that the military, public safety, agriculture, rail transport, and other essential sectors get first call on the available resources. Residential heating will get second priority when it comes to distilates and propane. That is not going to leave very much liquid fuels available at all for privately-owned automobiles. There just isn't going to be enough for more than a fraction of the motor vehicle miles presently traveled. That is the very hard fact that is looming in front of us. We have discussed in detail the various implications of this: the probable shift to electric vehicles, the expansion of mass transit, the growth of car pooling, the shift of people to bicycles or walking, and the wholesale redistribution of settlement patterns away from the automobile-centric model. My point is: none of this is academic or theoretical, it is real. Everyone had better take it seriously, and start seriously considering how you are going to adjust your lifestyle to adapt to this approaching reality.

Until the events of the financial crisis/bailout, I would have found it hard to believe that the US government would have issued a plan to disrupt liquid energy markets in a manner designed to DENY the public access to motor fuels.

Now I'm not sure, but I'd still doubt it. Forcing petroleum refiners to sell to public agencies first (at a set price, no doubt) sounds like a difficult proposal to pass.

I suspect that the threshold for FedGov intervention is going to be pretty high, and will attempt to preserve market pricing as much as possible. The driving force in this is likely to be when the military starts finding itself repeatedly outbid for fuels and starts coming up short.

Just a quick comment on government allocation of fuel. You seem to believe that in a shortage situation the US Government will sit down and make rational decisions on fuel allocation.

My personal opinion is that the US Government will allocate fuel first to itself (military, services like police and fire, and then to other government vehicles). The second allocation if any fuel is left will go to whichever demographic is likely to reelect the politicians in power. Private commuters have a lot more political power than agriculture or the transportation industry.

I doubt that government fuel allocations will be on a basis of what is best for the country overall. It is my sincere hope that I am wrong.

I share your scepticism. It won't be very rational, it won't work very well, and it will be larded with corruption and favoritism. But I very much doubt that ordinary people like you and I are going to fare particularly well in any scheme that the government cooks up.

WNC Observer,

If we discount that the world is going to enter a depression or total economic collapse, in which case there is not point in planning for the future, it seems that the US by 2020 will have to manage with no more than 7 million boe per day, including heavy oil and tar sands.

It doesn't seem credible that GTL or CTL can provide any significant contribution by 2020.

For this reduction to occur without causing economic chaos, five conditions would have to be met;(1)real prices must have a steady rise x2-x4 over the next 11 years (2) average vehicle fuel efficiency will have to be >50mpg with new vehicles >100mpg. (3)a 75% reduction in truck road transport tonne/miles, and a 50% reduction in light vehicle miles using ICE travel (4)a 50% reduction in air travel miles and a 50% increase in fuel economy of air travel.(5)replacing all heating oil by electricity and NG and some LPG with NG/electricity.

All of these conditions are possible with some government action:

(1)gasoline and diesel excise taxes could be used to ensure a steady 20% pa rise, increasing when world oil price declines and decreasing somewhat when oil price increases. Without government intervention price rises are going to occur but will cause price shocks.

(2)Present fuel efficiency standards of 27.5mpg could be raised to 40mpg by 2014 and once sufficient PHEV and EV capacity is in place raised progressively to 100mpg by 2020. The target should be to have 80 million households with one PHEV or EV that can be driven without using any significant amount of diesel or gasoline. I would expect that there would still be 100 million vehicles that only average 27-40mpg but these would be used 50% less( as second vehicles) or owned by people who are retired or commute to work via mass transit.

(3) a 75% reduction in truck transport tonne/miles due to a shift of long distance transport to rail and some reduction in long distance transport.

(4) x4 higher kerosene prices will increase airline capacity use, reduce less efficient small aircraft use and reduce overall passenger miles traveled.

(5) Replacement of all oil used for heating and some diesel used by medium trucks with NG. Some LPG used for heating could be replaced by CNG allowing LPG to also be used by truck transport.

This is only possible because the US had such a high capacity for electricity production(30-50% higher than most other developed countries). Even without expanding this capacity, conservation of existing electricity use could free up 30-50% for use to replace NG, LPG to be used for vehicle transport.

The most difficult task will be to ensure that most vehicles manufactured after 2014 are PHEV or EV. This will require a "war" effort re-structuring, but with US manufactures in deep financial difficulty the next US administration is going to have very high leverage to at least start the auto industry down this path.

There may very well be some movement along most or all of your five fronts. I rather suspect that whatever the government does along these lines is pretty much going to end up being a case of "too little, too late". Nevertheless, just about any deliberate progress along these lines will be helpful.

I anticipate that what is really going to bring demand into equilibrium with this permanently lower supply level (and your projections differ only slightly from mine) are "lifestyle changes" (to put a nice word on it), or "demand destruction" to be more blunt about it). Most people are simply going to have to learn to live with less energy in general, and liquid fuels in particular, because they simply won't be available (maybe at all, or at least at a price that is affordable for most).

There are several big lifestyle changes that can make a big difference in demand, and do not require a government program to make them happen:

First, I suspect that by the time we get to those reduced levels, it will be pretty rare to see a car on the road that is not full of people. People won't like it, but they can adjust their lives to share rides to a much greater extent than they do at present. This would be a big change and would have a big impact.

Second, I suspect that there won't be anywhere close to enough mass transit of any type available, but whatever is available will be jam-packed full. I furthermore suspect that additions to mass transit capacity will be made to the extent that resources (especially money, which will also be scarce) allow. I suspect that we'll see a lot more local shuttle buses, because this will be the easiest thing for cash-strapped municipalities to add quickly. I also suspect that we'll see more vans and SUVs being used for local jitney and cab/limo services, licensed or unlicensed. All of these will be jam-packed.

Third, we will see more people walking and bicycling. Walking costs nothing (except maybe to buy a good set of walking shoes), and bicycles are affordable for most people. I doubt that everyone will be on foot or bicycle, all the time, but these are things that are affordable, and that most ordinary people thus can do.

Fourth, I suspect that most people will be staying put a lot more. People will not be traveling just for fun, there will have to be an important purpose to justify a trip.

Fifth, while I think it will take a long time to undo our automobile-centric suburban sprawl, by 2020 there will be the noticeable signs that the great migration and transformation is well underway. Homes that are close to workplaces, or to mass transit nodes that can get one to a workplace, will be in high demand; homes that are isolated and inaccessible will increasingly be vacant, unsold, foreclosed, abandoned, and maybe even torn down for salvage. This will not all happen overnight, but rather household by household, year by year.

This could happen a lot sooner than you think. Every TODer should read and bookmark this article:

http://www.prudentbear.com/index.php/commentary/featuredcommentary?art_i...

The upshot of default is the US would not be able to import ANY petroleum. Why? Because nobody would take our (worthless) money. Re-allocation is a mild term to describe the consequences of a default.

As for electric other 'novelty' vehicles, there is something else to consider; the effect of 'reverse scaling' on the auto industry.

The worldwide auto manufacturing business is extremely capital intensive. An assembly plant costs billions to construct and each model line requires its own assembly plant. The cost for a Toyota assembly plant in Indiana is $3.6 billion.

http://www.toyota.com/about/our_business/operations/manufacturing/tmmi/

These plants require just in time deliveries of thousands of different parts which in their turn are manufactured in their own plants. A Toyota assembled in Indiana is made from parts from Japan and twenty or so other countries. The total capital expense of all model lines plus operations expense is divided by the number of of units sold. The enormous scale of the enterprise is absolutely dependent upon the sale of millions of units, since the expense is largely fixed, reducing the number of units sold results in escalation of the cost per unit.

There is no real escape from the cost basis in this industry; the US manufacturers historically invested less in machines and more in human capital. Consequently, General Motors is known as a 'healthcare company that also makes cars'. The Japanese makers pressed the trend to robotics and automation of the factory which requires less manpower but more initial capital. In either case the low unit price of all automobiles is dependent upon the volume sale of millions of units.

The electric/hybrid vehicles that are marketed are subsidised by the much larger numbers of conventional vehicles that 'pay down' the capital expense of the alt-fuel vehicles. Price parity between alt-fuel vehicles and conventional vehicles is maintained by the greater sales and profitability of large vehicles such as pickup trucks and SUV's. Reducing the sales of the conventional vehicles and the unit price of alt-fuel vehicles climbs.

Scaling alt-fueled vehicles is daunting. There is no agreement about what the endpoint of the technology is; climate change amelioration or fuel economy. The lack of agreement as to a goal makes the tech approach a guessing game. There is no agreement as to the best technology to achieve either end; unlike conventional vehicles that all use some form of internal combustion engine, either gasoline of diesel, the alt fuel possibilities are distracting: natgas, hydrogen, fuel cells, plug-in electric, hybrid electric, 'clean' diesel, alcohol, etc. This exists within a marketing envelope that requires all cars to be over-powered and 'loaded' with watt-gobbling 'luxury' accessories. Battery issues constrain electrics in general; manufacturing a small number (less than a million) Prius's with the existing cost basis would require each Prius to cost about what a high-end luxury car or semi-tractor would cost today. Both of these latter-types of vehicles are made in limited numbers; even the smaller capital bases relative to the smaller number of units produced translates into a much higher unit cost. Volume is directly related to price; increases in price drives demand downward in a vicious cycle.

Higher price does not have to be nominal, only the price of a vehicle relative to other goods and services. Actual price of a vehicle could decline (deflation) but the means to pay would decline more.

Since the existing cost basis of auto manufacturing cannot be 'wished away' (or sold the Treasury) only by marketing larger numbers of conventional gas-powered vehicles can Toyota sell its hybrid model inexpensively ... a process that defeats the purpose of the Prius's existence in the first place.

Other dynamics of the industry such as sunk capital, the need to change features/models constantly for marketing purposes and regulatory/financing restrictions are not in the favor of the industry; these add to overall cost. Take away a small amount of sales and bankruptcy looms.

Auto industry faces unit cost increases, less available credit and sales drop. As sales drop, manufacturers cut prices, as profits fall the manufacturer cuts models, features, and availability which hurts sales even more. Eventually, the companies drown in red ink; the spill-over is ex-employees in related industries who are unable to buy new cars which cuts further into sales which cuts profits ... and so it goes.

The epitaph on the post-modern auto industry will be, "Here Lies Economy Of Scale"

Brillant !

This is important because I believe that re localization is really the only way to deal with peak oil longer term. But we have a huge problem asset values are based on inflationary fiat currencies and long term debt and last but not least economies of scale.

We need to transition back to a economy with a much smaller capitol base and the willingness to invest in small ventures.

From the big picture this means in my opinion that most asset classes will effectively drop to zero value as only enough investment money exists to bootstrap the new businesses. This means land, building etc probably have to drop to practically no value to allow marginally profitable businesses to spring up. And since these sorts of economies are agrarian/commodity focused real commodity prices need to increase to the point that farming just above subsistence is reasonably profitable. In short we need sweat equity to have some worth.

You have to create opportunity and given that we expect oil resources to be in decline this opportunity probably has to be created by overshooting at the bottom. Values for assets have to drop too low. Market opportunities for the small localized farmer or entrepreneurs have to become compelling and first and foremost banks have to accept that this is now the only game in town. This is important since I think banking will be the slowest area to adapt to the new economic conditions. This means we almost have to go through a period of decay with empty building and idle farmland before banking finally admits that supporting the budding local farmer is the best use of money.

Also of course on the other side this new potential farmer would not have to ask for a lot of investment to start cash flowing. This in turn implies that prices for input would have risen to such a level that economies of scale no longer function !

For us at least the implication is that oil prices have to go to such a high level that it literally cost the same to manufacture in china as the US. Also of course wages would have to equalize.

Given where the world is today it just seems like we collectively will have no choice but to become poor globally before Economies of Scale is beaten.

It seems to me that ELP (Economize Localize Produce) implied a society where the amount of money in circulation is a lot less than today. Not exactly a barter economy but one thats in a sense 1:1 with barter. Small suppliers supplying small markets.

Steve,

You could have used the same argument 20 years ago to prove that SUV's would never become mass produced. PHEV and HEV's use similar platforms, most of the same components, wheels, body panels, engine, seats, etc.

GM appears to be designing in the Chevy Volt a PHEV power-train that can be installed into a wide range of vehicle sizes. The missing driver is $10 gasoline prices. When it comes, replacing 220 million obsolete ICE vehicles will provide the mass production volume to give "economy of scale".

GM doesn't have to build new assembly lines, just re-tool SUV and light truck lines, replace 4-5 L V8 engines with 1.5 L 4 cylinder engines, electric motors and much larger batteries.

This would be easier to accomplish if bad debts at the micro level could be written off through bankruptcy rather than socialized by endless bailouts and rescues. The bad will always always be hanging around waiting to drive out the good, even after a default, making any sort of recapitalization extremely difficult. Micro- economies in that case would be the only viable alternative; localities are having fiscal problems, too. It is hard to see how any regime would take root without some rational strategy in place to deal with 'old debt'.

The Supreme Court could declare the US government bankrupt and dissolve its debts. It's a serious solution ... seriously. Hey ... conflict of interest? Get the World Court to do the same thing.

...

It's ironic you would make this remark almost thirty years to the day after the Federal government bailed out Chrysler Motors.

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,947356,00.html

The auto industry has always been chained to the past by investment decisions which have repeatedly jumped up to bite it in the collective ass:

The makers have their multi-decade investments in large, conventional vehicles hanging around their necks like millstones. Let's try a thought experiment: consider a strategy that has US makers importing small, conventional vehicles from subsidiaries in Europe where the infrastructure for small vehicles already exists. Production from existing European facilities could ramp up to produce an additional million or so vehicles per year. These run on diesel, which is available and the economy of these vehicles exceeds that of the hybrids and plug-ins.

This presumes the goal of this exercise is to conserve fuel.

- The past investment of billions in plant for conventional vehicles would still have to be recouped or written off.

- The US public does not like Eurocars. Selling a million would be tough, like selling a million accordions.

- The makers, including Japanese and Korean, are competing with themselves. The demand backdrop twenty years ago was very forgiving, with a continuous increase in overall demand, stiumulated by midsized cars such as the Ford Taurus. The demand backdrop today is one of decline, if only because of the millions of second-owner vehicles available. This inventory overhang is a competitor for the makers, as the credit environment makes financing a new car much more difficult.

- Building 10-15 million Eurocars here would require billions in new facility investment which the companies could not obtain under any current credit circumstance. Even if the Treasury takes over or recapitalizes existing pension/healthcare/credit/facility overhangs, there will be little new capital left for anything other than the continuing manufacture of conventional vehicles.

The devalued money approach is becoming more tenuous as it gives creditors a good reason to be leery of it. The real problem is the 'debt bulge' is taking place in an environment where our creditors ALSO have economic problems ... which might require one of them to raise cash by selling dollars and securities for another currency. A run on our money could start somewhere and we would be powerless to stop the avalanche. As far a 'safeguards' there are credit and interest rate swaps. The interest rate swap market is very large - $450 TRILLION. Supposedly, an investor can hedge with these instruments, as everyone has seen, this protection is more theoretical than factual. At bottom safety is 'insured' by the amounts of foreign-denominated cash available in self-interested central banks; if the Koreans decided to dump dollars for Yen, the Treasury would (frantically) call the Bank of Japan and Bank of China to quickly provide a market ... the US doesn't have enough foreign currency reserves than to do so itself.

The run would be on at that point.

It will take a lot of 'mental disinvestment' in obsolete ways of planning. It is hard to see it happening from the top down:

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/21/business/economy/21fed.html?hp

Hello Steve from Virginia,

Well said. Consider that a recycled Ford Expedition might make 3 Spiderbikes + 500 yards of light, narrow gauge track. Now your talking a useful postPeak expedition...

Thanks for the post and link Steve. I have been wondering why the US seemingly did nothing to stem the fall of the dollar and suspected that they didn't because it provided a convenient way to pay off debt with devalued money. I also wondered if there is any kind of adjustments for exchange rates written into IOUs for debt. The link provides substantiation to my first suspicion and indicates that there are no safe guards built into debt purchase to protect the buyer. Thus, it is a buyer (of debt) beware system. Thanks again.

steve from Virginia,

Thanks for the link to the Prudent Bear article. It provides a wonderful synopsis of the manifold economic problems now facing us, touches upon the human aspects, and strikes a very nice balance between gloom and doom and optimism.

Like the author of the Prudent Bear piece, I too believe that, if the country makes the right decisions, its people can emerge from this with a lifestyle that, although not nearly so extravagant as before, may nevertheless not be lower in quality. In fact, it may represent an improvement in quality. This, however, will entail a retooling of the country's values, attitudes, moods and belief structures. This will take time, and it will not happen without a great deal of pain. The big question is: Can we get there from here?

My main fear is that the country will be torn asunder by social conflict--class and cultural war if you may. As Daniel Yankelovich pointed out in Coming to Public Judgment, if this is to be avoided in the future, "the nation will do once again what it has successfully done in the past: it will revitalize its traditional ideal of equality of opportunity. This is the only strategy that has worked in the past to reconcile the conflicting interests of liberty and equality, rich and poor, rural and urban, North and South, East and West, employees and employers, men and women, young and old, Catholics, Protestants and Jews, and above all, the ethnic minorities who form the pluralistic core of American life."

"Equality of opportunity," however, was much easier to provide in a previous era when there was, as Jack Kennedy put it, a "rising tide that raises all boats." As the tide ebbs out, we now face challenges we haven't faced in previous epochs.

Yankelovich points out another problem that plagues the United States:

TOD plays an invaluable role here--trying to raise consiciousness of the impending energy crisis, and its consequences, before it is too late.

I suppose where I differ from many commenters here on TOD is that I believe, in the event the social order gives way and we revert to some sort of medieval existence, or worse, that no one will be safe. Some seem to believe they can create some sort of Waldenesque utopia, isoloated from the caos sweeping the nation and the world. This is wishful thinking. If the social order gives way, there will be no place in the country that will be safe from lawless bands of violent marauders.

Therefore I believe it is incumbent upon all of us to work for the preservation of the social order. The ideals of "rugged individualism" and "the imperial self" are very much part of the American ethos and, in moderation, are certainly benign and even beneficial. But taken to an extreme, they only encourage the formation of an "everyone for himself" attitude.

The social order issue is a worrying one. In my mind, that is what largely forms the boundary between "decline" and "collapse". I believe that we individually can cope with and navigate through decline; I am not at all confident that any collapse scenarios are survivable for more than a small minority, and then more by luck than anything else. There is always the possibility out there that decline might cross a tipping point, perhaps triggered by some "black swan" event, and spiral into collapse. I do not view this as a certainty, only a possibility. I am not confident of my own prospects for surviving a collapse, no matter what I might do, so I don't worry much about it. My focus is on trying to cope with decline; mapping out the possible or likely contours that decline might follow is helpful for that.

Steve:

Good post.

With regard to your first point, I do indeed worry about scenarios in which the US is forced into an actual or de facto sudden default, followed by a sudden curtailment of oil and other imports. It could happen. This is why I am warning people to take the looming reduction in available liquid fuels so seriously, and to not wait until "later" to begin adapting to this future scenario in the vain hopes that it might not come to pass. As you point out, it might very well come far sooner than any of us anticipated.

As for vehicles, I have mentioned in other posts that I suspect that the fate of a considerable number of compact and subcompact automobiles now on the road (and those to be added to the fleet in the future) will be as conversions to EVs. It is feasible to do this at a cost of under $10K or so. So far, only a few experimenters are doing this, but once gasoline starts to become really expensive and in short supply, I suspect that interest will increase. Perhaps we'll get some economies of scale with these conversion components, driving their price down a bit. I see most of these conversion EVs being powered by whatever conventional lead-acid batteries that the owners can manage to scrounge up. These will be vehicles that are slow and have a very short range - just good enough to get them to the grocery store or nearest mass transit node. That will be good enough for a lot of people that would otherwise end up with no form of motorized transport at all.

As for your points with regard to economies of scale in automobile manufacturing, one thing that works a little bit in our favor is that EVs, and particularly NEVs, are inherently more simple vehicles and require fewer materials and components to manufacture compared to conventional ICE automobiles. I don't know if it will be possible for any of the Big Three to transform themselves into a maker of EVs and NEVs. I rather expect that the accumulated burdens of the old way of doing things will weigh them all the way down into bankruptcy. However, I do expect that one or more new enterprises will then snatch up the choice bits amongst the debris and use them to build manufacturing facilities that are scaled appropriately to EV or NEV technology and projected market demand. Even with this, though, I don't expect NEVs, or especially highway-capable EVs, to ever be cheap. Purchase of a new purpose built EV, or even an NEV, will be out of reach for the majority of households. This is why I expect to see a lot of conversions of older compacts and subcompacts, as that will be the only option that will be affordable for a lot of people.

This article from LA Times caught my eye:

http://www.latimes.com/news/science/environment/la-fi-ultramile9-2008sep...

The mid-1980's subcompacts ate gas stingy, even moreso than the newer models. No doubt the survivors can be fitted with batteries and motors which are now purpose built. A better battery and more efficient, lightweight motors would make be the logical improvement. The question is, will these ever get to a market?

Another article describes the difficulties of bringing ideas to the public when the capitalization baseline is a rapidly moving target:

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/05/magazine/05Green-t.html?scp=9&sq=ventu...

What comes next is hard to predict because of the financial mess. In a perfect, non-indebted world, the best approach would be a comprehensive set of priorities of which transportation would be a part of the whole rather than an end in itself. Unfortunately, the choices may already have been made, we just don't know about them yet.

Gail

Could you redraw the headline graph and remove tar sands from canada (let's just assume that if oil is under $90, that increases in tar sands production stop, and we actually see decreases). I'm more interested in the shape of the curve than the absolute, because if canadian production falls due to this, presumably their demand won't fall as much so exports to US. will decline.

The Canadian situation is complicated. They are an importer of oil from the East coast. According to BP Statistical Data, in 2007, they imported 1,357,000 barrels per day of oil and petroleum products. This oil is from various sources. The people on the Eastern side of Canada use this imported oil.

Canada has both conventional oil production and oil sands production. The conventional oil production has been declining for years. Both the conventional and oil sands production are located in the western part of Canada. Some of this is refined and used in Canada. The rest is shipped by pipeline to the US to be refined.

According to BP, Canada consumed 2,303,000 barrels per day in 2007.

Exports to the US will decline for any of the following four reasons:

1. Canada is unable to import as much oil from overseas as in the past.

2. Canada's conventional oil production declines.

3. Canada's oil sands production declines.

4. Canada's consumption increases.

I will look up the breakdown on the oil sands and the conventional oil, and post what I find.

Interesting, does this mean that if the environmentalists managed to shut down the tar sands we would be compelled, by NAFTA to become a net exporter to Canada?

The following is a graph of recent historical and forecast Canadian oil production by the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP). It doesn't do exactly what you asked, but it shows that conventional production has been declining and is expected to continue to decline in the future. The forecast for oil sands production is almost certainly way too optimistic with the current credit crunch. Also, with peak oil, the crunch for long-term credit is likely to be around pretty much indefinitely.

Looks to me like the only existing major source for imports that has much upside potential is Iraq. The declines from Mexico and Venezuela will continue. But I'm less clear on Nigeria. What's going to happen with Nigerian production?

I think we are in a period which is like the last party before the storm. Gasoline getting down around $3 per gallon. Might be the last chance to take a long country drive - at least if you don't think you are about to get laid off.

NIgeria has been having serious problems with declining exports because of increased violence in the country.

This is an article that appeared in the last couple days, saying that production had declined 20% because of violence. I don't think anyone sees any way this will turn around in the near future.

Great post Gail.

Also not sure you saw my post on the drumbeat but when you start adding in the embedded energy in food exports then the situation is even worse for Mexico. It would be complex to do a complete balance of trade analysis and calculate the embedded oil energy in the products but as a oil exports becomes marginal the energy flows in other forms of trade become significant.

The US as a large food exporter is exporting quite a bit of embedded energy back out from its oil imports to pay for drumroll... oil imports.

And one finaly note and its related to food. I've been of the opinion that most of the demand destruction in the US is coming from the collapse of the housing industry. For some time now I've assumed we really don't have another fuel intensive industry that can collapse.

However we do its the farming industry. Its the silent bubble that people don't talk about much but there as been just as much speculation in farmland as in housing with land prices now at insane levels. Hedge funds are deeply involved in this. This is the next bubble thats going to burst. And it will have a large effect on US food exports.

Sorry to bring that up in this thread I'll continue to posts warning in the drumbeats.

But as we go forward we need to watch how US industry collapses obviously housing first followed by commercial real estate then probably farming then auto industry and finally at some point the US oil industry which has a low EROEI will collapse.

As I said I'll post more on this but I just wanted to bring it up as I start thinking about net energy flows and the coming collapse of oil based industries.

With the current price of grains and other crops, it is virtually impossible for farmers to make a go of it financially. There will be massive default on this debt, just like all the other. This is one of the reason that all of the models underestimate the amount of debt out there that is likely to default in the months and years ahead.

These huge farms only make sense with huge farm equipment. If we have to use a less energy intensive model, there will need to break these farms into smaller sizes and provide local housing for the new farmers. It is difficult to see how such a transition can be made within our current model of farm ownership.

One issue that interests me is that in investigating the purchase of a small piece of country land recently in the southern ontario corn-growing area of Canada, I discovered to my surprise that the land, even in areas so remote from cities that they can have no spec valuse re development, is selling at something near ten times the traditional farmland valuations which have been based loosely on the 50% of sell price of crops as annual rent. I think corn would need to sell for something like 5 to 10x present prices to justify recent "market price" of farmland here.

So my question is, is this just another irrational bubble waiting to burst, or do some wealthy people know something about future crop prices which the rest of us don't? Interesting.

This item from Britain is also interesting.

Bubble!

A couple of long-time family-farmers I know categorically state that the only way to break-even at farming is to already own the land outright. They say it is flatly impossible to pay a mortgage on farmland and support yourself farming, and even then only larger farms (thousands of acres) can really survive.

YMMV -- local scuttlebutt only.

I can certainly believe that. For most of human history, most farmers have lived on the brink of financial disaster. The only farmers that have ever really lived anything close to comfortable lives are those who were fortunate enough to own their land outright. This one fact explains why there was the absolutely huge migration of millions upon millions of people to the US in the 19th century - the Homestead Act was a unique opportunity, and they all wanted to take advantage of it.

If one wants to farm and does not own their land free and clear, then one had better have something else to bring in some money in addition to the farming. There are a great many farmers who work at full or part time jobs on the side, or have some side business selling insurance or something, and whose wife holds down a full or part time job as well. If they are lucky, the farm itself at least breaks even; they are doing well to do even that good, not everyone is so lucky.

Maybe what we need is a new Homestead Act. The Government could step in to buy farmland that has been foreclosed, and then turn around and distribute it to qualified homesteaders along lines similar to the rules of the original Homestead Act. Families get just enough land to be farmed by a single family, with only small scale and inexpensive mechanization, but they get it free and clear if they stay on the land and work it for several years.

At this point, I am not sure current owners would appreciate it. Also, we would probably need to build new homes closer to the workers. I would guess these would be much simpler, closer to those of the original homesteaders.

Memmel

I realize that you have huge industrial farms in the US but I doubt they will be allowed to fail. Also food has a stable demand and I would have thought reasonably inelastic, so any shortage will cause price increases, These will be sharp as the world food stocks are at all time lows (35 days).

I see your point in the housing industry, but the quantity of it (in sq feet) has probably outpaced demand now.

Neven

With credit problems, things don't always work the way a person expected. If some of the buyers of grain (middlemen, or those who ship grain overseas), this could depress the price of grain. I expect that this is at least part of what is happening now.

Once the problems start feeding through the supply lines, we could have real problems in terms of available food supplies. I am not sure a run-up in food prices would solve the problem.

Gail

I agree but also think with the current credit turmoil and the global nature of grains that there will be some 'indicator' issue first, like a first world country having to ration a staple (thou this will be proceeded by food riots elsewhere).

My opinion is that some of the doom scenarios that are predicted are too 'orderly', for example credit crunch = house foreclosures, but a what point are there so many foreclosures that this process (which is the option of last resort in a functioning banking system) become nonsensical?

I'm not sure what you mean by "what is happening now"? Farmers always complain about the price they get but continue to farm (Many farmers in NZ are asset rich, cash poor), But if there was major destruction of production then the rules change, food is currently so little of our cost of living we take it for granted, that may change...rapidly

Neven

To be clear this is a collapse initially of land prices which are in a bubble and certainly some of the large mega farms that are hit by the credit crunch this will just help send land prices into a tail spin. Breaking up the farms in to smaller ones that are more manageable with smaller equipment is probably a long way off and in any case would require a lot lower land price to entice people back into farming.

My best guess is we will see falling land prices for at least fifty years if not longer.

Also it could be as long as five years before we see a significant drop in food production. People can and will plant all the way down and I'm sure subsidies and all sorts of support will be used to help the poor mega farmer farm. But this will not prevent the collapse of farm prices and it probably won't go far to helping farmers receive credit.

I'm not well versed enough in farm crisis although we have had many to predict the exact outcome and esp predict it without knowing the prices for oil and NG as the collapse progresses. My opinion is that even with tons of help farming will not be profitable and farms will continue to fail with crop levels dropping. Most of the increase in prices for food will be eaten up by ever higher operational costs so profitiability will be low.

Remember the last time people moved en-masse to farm in the US the land was give away for free. I see no reason why we won't end in the same place with free farmland used to entice poor city dwellers back out to the farm.

The US has no shortage of farmland and realistically probably never will. However it will probably be a while before farmland prices drop enough to grow row crops without oil. The problem is of course farming has huge upfront investment costs even if you go entirely with alternative approaches.

You could give me 40 acres of land for free and it would be a long time before I could grow the production on the farm using just the profits for investment.

So overall for us to transition we would have to see land values drop close to zero and food prices skyrocket to the point that subsidies are no longer needed before we probably can invest in smaller less oil dependent farming.

But back on track the farmland price bubble has been overshadowed by its bigger cousin the housing bubble but I'm predicting it will pop with a vengeance next year.

http://media.www.dailyillini.com/media/storage/paper736/news/2008/09/11/...

http://www.farmdoc.uiuc.edu/manage/newsletters/fefo07_15/fefo07_15.html

And to give you some idea of what I think they will have to fall to for it to make sense to make a major capitol investment in a smaller farm. My best guess is about 200 and acre. Thats a 96% drop in value from 5000 -> 200.

In the 1970's farmland was around 400 and acre with reasonably cheap oil.

Gail - Thank you for bringing up the key issue of imports.

How do you think this will effect US imports if it comes about?

"ECB's Nowotny Sees Global `Tri-Polar' Currency System Evolving"

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601087&sid=apjqJKKQvfDc&refer=home

"European Central Bank council member Ewald Nowotny said a ``tri-polar'' global currency system is developing between Asia, Europe and the U.S. and that he's skeptical the U.S. dollar's centrality can be revived."

OUCH!

This combined with the fact that the US no longer controls who is head of IMF or is it world bank. I think something is in the works.

Any kind of rearrangement of the currency away from the centrality of the dollar is likely to reduce US imports substantially. Our balance of payments situation has been ridiculous for years. Anything that forces a change in the direction of our actually having to pay for what we buy will result in a huge drop in imports.

Thanks for the link by the way. It seems like some kind of currency change is inevitable, whether this one or some other.

One thing I should mention is that it is very difficult to really track where oil comes from, especially if we import a refined product.

Suppose we import gasoline from Netherlands. Does that mean that crude oil that produced the gasoline came from Netherlands? Not likely. I would expect that most of the gasoline imported from the Virgin Islands came from crude oil that was imported from Venezuela. One really has to go back to where the crude oil that produced the product we imported came from.

We also have the problem in Canada, where Canada is dependent on imports (from the East), and at the same time sends us exports (from the West). If there is a drop in imports, I would be willing to bet there will be a drop in exports.

Ultimately, we depend on the crude oil from the crude oil exporting nations. Trying to add up where particular imported products are from doesn't really tells the whole story.

Thanks Gail,

so imports is going down + US production is going down = US consumption is going down. This seems to go in line with the BP statistics (http://www.bp.com/statisticalreview) that shows decreasing US oil consumption since 2005.

Recently I did a similar data check (BP data and EIA data) in order to see which countries still can increase their exports of oil, gas and coal.

I mainly did simple statistics, so guys like Colin Campbell should have more accurate information for oil, but as a start it was okay for me. The list of "rising oil exporters" is pretty short. Probably less than a dozen countries can increase their exports:

OECD:

Canada (incl. oil sands)

OPEC:

Qatar

Angola (government announced peak, decline from 2014)

Non-OPEC:

Azerbajian

Kasachstan

Not sure:

United Arab Emirates

Nigeria

Algeria

Saudi Arabia

Sudan

If you think this is little then you don't know the number of future coal exporters: 6 (Russia, Colombia, Australia, Indonesien, Vietnam, Venezuela + the not sures: South Africa, Kazakhstan)

As a little solace: For natural gas there is still much more variety. I counted about 2 dozen countries (and don't talk about things like pipe network restrictions).

(I skipped checking the IEA data as it is too much work to compile them. These might look a bit more "optimistic" as they include more types of "liquids".)

Venezuela can increase production in future. They have a huge heavy oil resource on par with Canada's tar sands.

Personally, I feel that they're being prudent by investing heavily in social capital and letting oil production slide for the time being. The oil will be there tomorrow (when it can be sold at an even higher price), and the returns on social capital can be enormous.

Yes, my list probably missed a few countries which export history was distorted by "above ground" reasons: Iraq, Kuwait, Iran and Venezuela. These should be added to the "not sure" group, as it is far from sure how the "above ground" environment will develop in the future.

For Venezuela I can well imagine that they could improve their production efficiency (for example in coal production they still use trucks instead of trains to get the coal from the mines to the coast). According to Bloomberg Chavez, who not long ago had been busy to chase private oil companies out of his country, recently called for new investments and even talked about tax rebates. Who knows what is going on there...

Whatever the list was before the current credit problems, the new list is likely a lot shorter with tighter credit.

I got a long e-mail from a reader today, talking about the problems in the Canadian oil sands project where is located, caused by today's credit problems. He sees a "dramatic turn-around in planning" due primarily to the credit problems. He expects new projects which are already quite far along to be scrapped, because of these problems.

I have often written that with peak oil, long term debt makes much less sense. Because of this, I think that credit problems will not really be resolved (there may be some partial resolution, only to get worse again later). Companies which are very well funded may be able to continue with new projects, but other companies will drop out.

Because of al the credit problems and the impact of these credit problems on the oil industry, we are probably past peak oil production.

Gail, your comment

I would side with you on this.

Would this mean that the trend post PO would be more short term debt?

This would make it harder to realize future capital intensive projects.

I think there will have to be a lot more government funding of projects.

There will be short term debt entered into by companies, but I expect this will mostly be to facilitate transfers from a seller to a buyer, or for other very short term purposes. Companies will have to finance their investments out of savings and/or cash flow, so I expect there will be many fewer of them and, as I said some government funding of large projects.

Gail,

Thx for your response.

This is (in my opinion) an important aspect of the credit crunch and PO subject to understand.

Could this be a subject for a separate post, as this could bring to attention the financial requirements of energy companies? Energy companies will now have to compete about fast dwindling credit with other industries. According to Norwegian newspapers some energy companies are now losing their credit lines and may face bankruptcies or take over’s.

That governments will have to take part in financing future mega projects is also a new, but probably necessary. This also suggests that future mega projects will become subject to political preferences/priorities and less would be left to the market to solve.

You are right--I need to be writing more about this.

Do you have any English versions of articles about energy companies losing their credit lines and facing bankruptcies?

I have also agreed to do an article for a new publication called "Journal of Energy Security" on some related issues.

Perhaps high dividend rates might make a comeback. It used to be that many utilities and railroads would finance their huge capital needs by selling common or preferred stock, and paying nice dividends to make the stock worth buying and holding. These tended to be good, safe investments, because usually (setting aside WSPPS!) these entities would have a very steady and secure cash flow to fund the dividend stream. That is why these types of stocks would be mainstays of "widows and orphans" portfolios.

In a low growth or negative growth economy, you can forget about capital gains, and even interest might be a little iffy. Dividend yield might be the most attractive game remaining.

The numbers are eye opening. Your figure 4 graph of US exports looks like another bubble. The question is how far will exports climb before the crash ...

My first impression is another example of the weak dollar's effect on trade. There is nothing compelling US refiners from shutting the door on US customers to service others overseas. There may also be a result of refinery pricing or delivery issues in Canada and Mexico.

Among the Arab countries possibly Kuwait is the most friendly country to US thanks to the First Iraq War and the liberation of Kuwait from the clutches of Saddam Hussain. It is surprising to see that Kuwait which has the world's fifth largest Oil reserves, does not figure in the top suppliers of Oil to US. The next President should aggressively explore increasing the import of Crude from Kuwait and also extend help in increasing the Crude production of Kuwait ( which at current levels could last over 100 years)