Further Evidence of the Influence of Energy on the U.S. Economy - Part 2

Posted by Gail the Actuary on April 23, 2009 - 10:25am

This is a guest post from Steve from Virginia. Steve's real name is Steve Ludlum.

Last week, Dave Murphy (EROI Guy) explored how increasing energy prices during the run up to 2008's $147 bbl peak affected purchasing power of consumers and subsequently the solvency of the establishment that relied on that purchasing power. He mentions James Hamilton:

Hamilton acknowledges early on in his report that the proportion of income spent on energy is an important determinant of consumer spending patterns. The theory is fairly simple: if energy expenditures rise faster than income, then the share of income for other things besides purchasing energy must decline, such as spending on mortgage payments for a second home in Las Vegas. In other words, rapid, large increases in energy prices may curtail consumption enough to trigger larger financial problems – like the bursting of a housing bubble – that when aggregated across an economy may cause or contribute significantly to a recession.

I will show an even greater connection between energy prices, interest rates, and the financial sector, based in large part on a review of minutes of the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC) from the end of 2002 to 2007. It appears the Fed’s inflation expectations were very closely linked to petroleum prices. Because of this, the rise in oil prices led the Fed to raise interest rates in an attempt to control inflation, which in turn had unintended consequences.

The US and the world's finance system uses an operating approach called Structured Finance. This is a system for the management of credit using assets such stock and real estate as collateral for highly leveraged lending. The products of this lending are 'Structured' into securities. This finance system makes money by borrowing funds at low rates such as LIBOR + 1 percent (2.5%) and lending at higher rates such as 6%. The system keeps the difference.

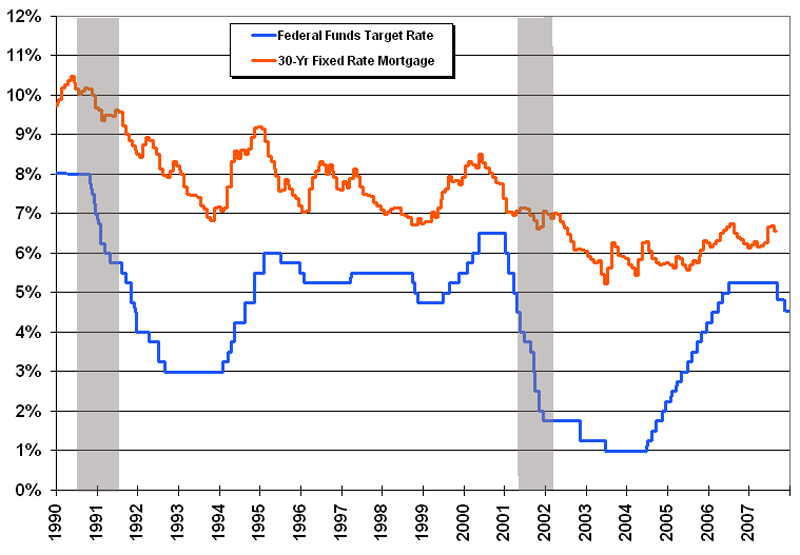

Here is a graph illustrating the relationship between the Funds target rate which represents the lowest- cost borrowed money and the 30 year conventional mortgage rate.

The difference or spread between the funds and mortgage rates at any given time represents return to the finance system. When the spread narrows as it did from 2005 - 2007, there is danger to the system. Rates follow a 'yield curve': lowest rates are short term and the higher rates are longer term. There is substantial risk that the system may be 'underwater' if short term rates rise after longer term loans are made at a low rate. The return from the longer termed security is inadequate to service the system's short-term money costs.

Structured finance is organized around the flow of funds. It applies the pricing effect of 'velocity of money' to capital assets rather than to consumables. Velocity of money is the rate of turnover of transactions within any given place and time. Repeat transactions have the same effect as a proportionate increase in the money supply. This effect was observed and described as the 'Quantity of Money' theory by Irving Fisher, derived from Ludwig von Mises, John Stuart Mill and originating with Copernicus:

If changes in the quantity of money affect prices, so will changes in the other factors—quantities of goods and velocity of circulation—affect prices, and in a very similar manner. Thus a doubling in the velocity of circulation of money will double the level of prices, provided the quantity of money in circulation and the quantities of goods exchanged for money remain as before ...

Raising the price of small items by virtue of everyone in town buying them repeatedly requires pocket change. Raising the price of millions of houses by tens or hundreds of thousand of dollars each or raising share prices of gigantic multinational corporations requires tremendous financial horsepower -- which is the end purpose of structured finance. By raising asset prices, collateral values are also raised. This allows more lending against that increase in collateral -- which then drives prices even further in a virtuous cycle.

Clever American financiers invented a sort of financial perpetual motion machine.

The Funds rate is a target set by the Federal Reserve system which is tasked with managing the nation's money supply. Its most important role is to control inflation. Eight times a year, the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC) which is made up of the seven members of the Board of Governors, the president of the New York Fed and four presidents of other Fed system banks meets in Washington to examine the performance of the economy and set short term interest rate targets. Records are published of these meetings and made public. These records are available online and a relevant summary is also posted on my blog.

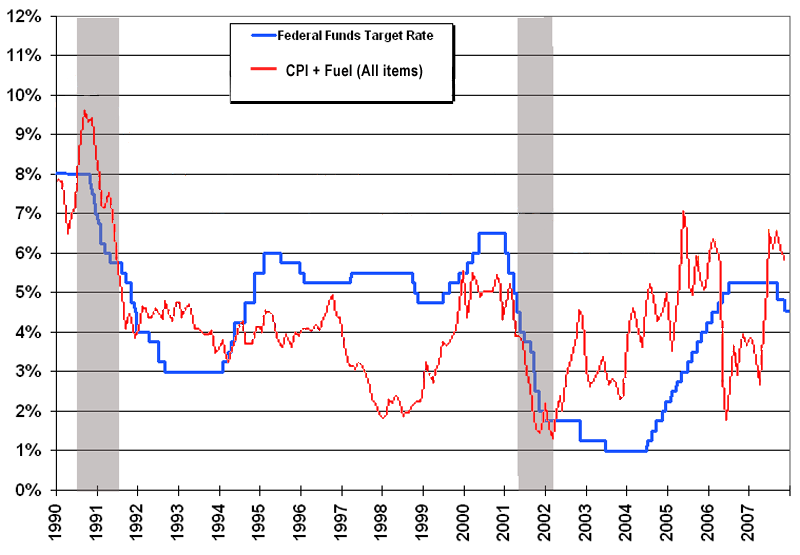

Figure 2 illustrates the Fed's response to inflation by its raising short-term interest rates. Increases act as a governor on demand by increasing the cost of credit. In recessionary periods, the Fed decreases credit rates in order to stimulate lending. The 'Open Market Desk' at the New York Fed performs this job by trading Treasury securities to commercial banks.

The background of our current situation lies in the remarkable period prior to 2002. Fed Governor (at the time) Ben Bernanke mentioned this period in remarks given in 2004:

Several writers on the topic have dubbed this remarkable decline in the variability of both output and inflation "the Great Moderation." Similar declines in the volatility of output and inflation occurred at about the same time in other major industrial countries, with the recent exception of Japan, a country that has faced a distinctive set of economic problems in the past decade.

A component of this Great Moderation was low and stable petroleum prices.

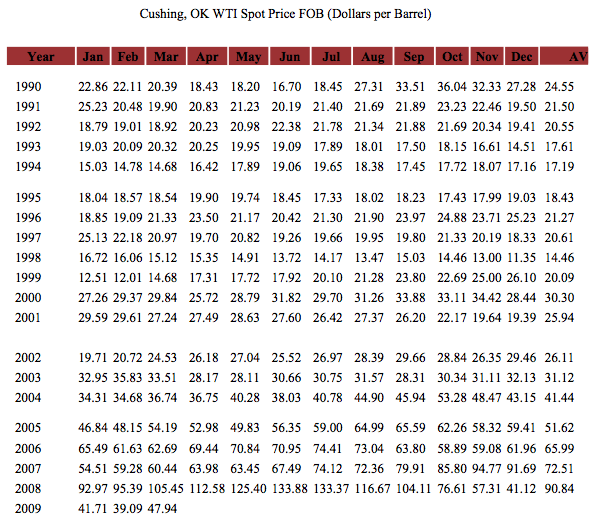

As can be seen, from 1990 until the end of 2001, energy prices remained within a volatility range between $20 - 25 with short periods lower or higher. The average price for the period was $21.04.

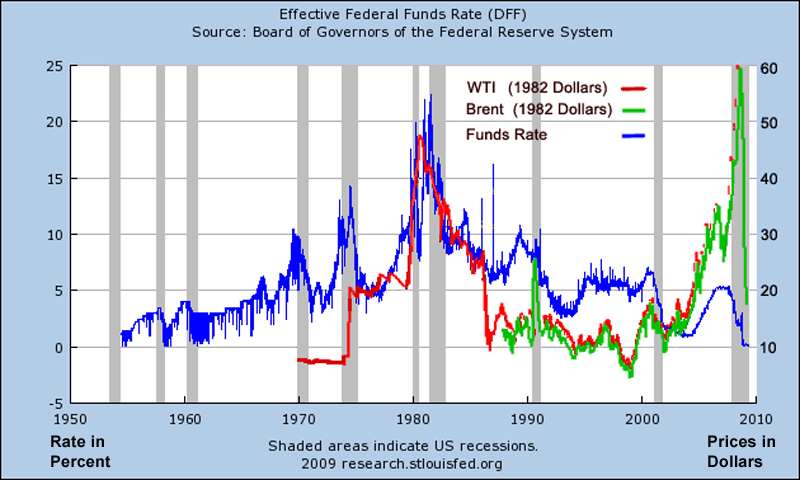

Energy prices and interest rates have a lengthy historical relationship. Figure 4 plots short term interest rates from 1955 alongside US recessions with energy prices in constant 1982 dollars.

The Fed is careful to watch energy prices as price increases directly contribute to inflation. As can been seen in the plot, rising interest rates and energy prices have preceded US recessions since 1973. Even the 1991 'Mystery Recession' was accompanied by a spike in energy prices after Iraq's invasion of Kuwait.

During FOMC meetings from 2003 - 2006 the committee cited rising energy prices and the inflationary effects of this rise at almost every meeting. Beginning in 2004, the Fed steadily increased the Funds rates starting in June. The year over year increase in energy cost can be seen in Figure 3: 2002 average price was $26.11, 2003 average was $31.12 and the 2004 period was set to average $41.44. This remark from the December 29, 2002 meeting is typical of the period. Note that the Fed uses different methods to gauge inflation:

Core consumer price inflation, as measured by the consumer price index (CPI) and the chain-weighted personal consumption expenditure (PCE) index, continued to edge lower through the end of the year. However, the sizable run-up in energy prices last year boosted overall consumer price inflation somewhat on a year-over-year basis. At the producer level, core prices for finished goods declined in November and December, but for the year as a whole the jump in energy prices pushed overall producer prices for finished goods up slightly. (Per- barrel price at the time of the meeting was $29.46) http://www.federalreserve.gov/fomc/minutes/20030129.htm

Overall inflation in 2003 was low with the exception of a steady rise in energy prices that are noted in all but one of the FOMC meetings. The Funds rate for 2003 was an extraordinarily accommodative 1.25 - 1%:. :

Total twelve-month consumer inflation was unchanged over the period owing to accelerations in food and energy prices. ($43.15) http://www.federalreserve.gov/fomc/minutes/20031209.htm

Total consumer price inflation, however, was boosted in January by a surge in energy prices.($36.75) http://www.federalreserve.gov/fomc/minutes/20040316.htm

In the United States, the core consumer price index advanced at a faster rate in the first quarter than it had in the fourth quarter, reflecting the pass-through of higher energy prices and a leveling off of goods prices after sizable declines last year. ($40.28) http://www.federalreserve.gov/fomc/minutes/20040504.htm

At the June, 2004 meeting the Governors voted to increase rates by 0.25%. They would do so at each subsequent meeting.

In light of the strength of economic activity and recent indications of somewhat increased price pressures, the members focused particular attention on the outlook for inflation. They referred to statistical and anecdotal evidence that on the whole pointed to some recent acceleration of consumer prices and to some increase in near-term inflation expectations. Factors cited in this regard included large increases in prices of energy and intermediate materials, both of which appeared to be passing through at least in part to core consumer prices. ($38.03) http://www.federalreserve.gov/fomc/minutes/20040630.htm

A year and a half later, in February 2005, the acceleration of inflation was an increased concern. Energy- cost for that year would average $51.62 a barrel. Rate increases had not slowed the increase in fuel prices but begun to constrain housing, which is credit sensitive. The emphasis at meetings was on sharply higher crude oil prices. The first hints of softening in the housing sector was noted in February 2005:

Moreover, the recent rebound in spot crude oil prices, and especially the substantial advance in prices of crude oil futures contracts for delivery well into the future, suggested that a significant unwinding of higher energy costs might not be in prospect. Several participants indicated that, in current circumstances, they viewed an upside surprise to inflation as potentially more harmful than an equivalent downside surprise, partly because such an outcome could well impart additional upward momentum to inflation expectations. ($54.19) http://www.federalreserve.gov/fomc/minutes/20050322.htm

In August, Katrina had hit the Gulf coast and its effects were noted in the minutes along with consequential energy price increases. Participants questioned the effect of higher energy prices on business investment. Inflation was a concern. The Funds rate was 3½ percent:

Participants' concerns about inflation prospects generally had increased over the intermeeting period. The surge in energy prices, in particular, was boosting overall inflation, and some of that increase would probably pass through for a time into core prices. This posed the risk that there could be a more persistent influence on inflation should inflation expectations rise. Indeed, some recent survey evidence on such expectations had been troubling, and widening federal deficits were mentioned as a factor that could further stir inflationary concerns. ($65.59) http://www.federalreserve.gov/fomc/minutes/20050920.htm

By the end of 2005 the increase in oil and energy prices had become a preoccupation of the Federal Reserve. The end of 2005 turned out to be the peak of the housing bubble: The funds rate had increased over the year from 2.25 to 4%. Here, the Fed makes one of its rare acknowledgments of the effects of its interest rate increases on housing:

Activity in the housing market remained brisk despite a rise in mortgage interest rates. Starts of new single-family homes dropped back somewhat in October from September's very strong pace, but permit issuance remained elevated. New home sales reached a new high in October, and existing home sales eased off only a little from the high levels recorded during the summer. Other available indicators of housing activity were on the soft side: An index of mortgage applications for purchases of homes declined in November, and builders' ratings of new home sales had fallen off in recent months. In addition, survey measures of home buying attitudes had declined to levels last observed in the early 1990s. ($59.41) http://www.federalreserve.gov/fomc/minutes/20051213.htm

At the January 31, 2006 meeting, there was more comment on interest rate effects on mortgage lending. Keep in mind that loan originations are by non- bank businesses that do not report to the Fed: After this meeting, Ben Bernanke replaced retiring Alan Greenspan as Fed Chairman:

In some areas, home price appreciation reportedly had slowed noticeably, highlighting the risks to aggregate demand of a pullback in the housing sector. For instance, the effects of a leveling out of housing wealth on the saving rate were difficult to predict, but, in the view of some, potentially sizable. Rising debt service costs, owing in part to the reprising of variable-rate mortgages, were also mentioned as possibly restraining the discretionary spending of consumers. ($65.49) http://www.federalreserve.gov/fomc/minutes/20060131.htm

In subsequent meetings during 2006 the steady rise in energy prices was noted: "registering a large increase in January that was driven mostly by a spike in energy prices.", "retail gasoline prices surged, leading to a jump in overall energy prices for the month", "sharp increases in the prices of petroleum-based products". At the July 29, 2006 meeting the funds rate was raised 5¼%. At this point, FOMC meetings contained two narratives, the steady increase in fuel prices and the ongoing deterioration in the housing sector:

In their discussion of the major sectors of the economy, participants observed that housing construction activity had declined notably in recent months as indicated by lower housing starts and permits; moreover, higher inventories of unsold homes, a sharp rise in cancellations of new home sales, and reports from construction companies suggested that the weakness was likely to be extended. Several participants pointed out that the decline was broadly in line with expectations in light of the tightening in monetary policy and the rapid run-up in home prices and residential construction in recent years. Participants also observed that the evidence to date indicated that the slowdown was orderly but were mindful of the possibility of a sharper downturn in the sector.

The growth of consumer spending had dropped off significantly in the second quarter from a robust pace earlier in the year. The slowdown was attributed in part to higher energy prices and also to a likely downshift in home price appreciation and higher interest rates. A reduction in the attractiveness of home equity borrowing was mentioned as possibly contributing to the slowdown. ($70.95) http://www.federalreserve.gov/fomc/minutes/20060629.htm

At the Treasury Department, the likelihood of a displacement was under discussion as early as 2005. The focus was both the effects of rising rates as well as a fuel price spike:

Secretary Paulson on this arrival in summer 2006 (DATE) told Treasury staff that it was time to prepare for a financial system challenge. As he put it, credit market conditions had been so easy for so long that it was inevitable that credit problems had built up that would lead to problems if conditions reversed.

From summer 2006 Treasury staff had worked to identify potential financial market challenges and possible policy approaches, both near term and over the horizon. The longer-range policy discussions eventually turned into the March 2008 Treasury Blueprint for Financial Markets Regulatory Reform that provided a high-level approach to financial markets reform. Consideration of near-term situations included sudden crises such as terror attacks, natural disasters, or massive power blackouts; market-driven events such as the failure of a major financial institution, a large sovereign government default, or huge losses at hedge funds; or slower-moving macroeconomic developments such as energy price shocks, a prolonged economic downturn that sparked wholesale corporate bankruptcies, or a large and disorderly movement in the exchange value of the dollar that led to financial market difficulties. None of these were seen as imminent in mid-to-late 2006, and particularly not with the magnitude that would eventually occur in terms of the impact on output and employment. http://www.econ.yale.edu/seminars/macro/mac08/Swagel-090409.pdf

That impact would be considerable; in February, 2007, Freddie Mac stopped accepting certain sub-prime mortgage securities for purchase. The crisis was officially underway: A barrel of West Texas Intermediate in Cushing, Oklahoma cost $59.28. http://timeline.stlouisfed.org/index.cfm?p=timeline

A number of conclusions can be drawn from these documents. One is that energy contributed to Fed actions. Another is that the current crisis has developed similarly to other US recessions. Even the geopolitical background - Mideast tension and war - is similar to other recessionary periods. The sequence of events is:

A rise in energy prices -> increased inflation -> higher short term interest rates -> a slowdown in credit-sensitive sectors of the economy such as housing and lending -> a general slowdown in the economy as a whole.

Mr. Bernanke outlines the sequence in his 'Great Moderation' address quoted previously. The large difference this time compared to other 'energy crises' is that there are no gas lines or odd-even rationing which would focus public attention on energy rather than on finance. In the past, inflation was constrained by punishingly high short term money costs along with new petroleum supplies introduced from North Sea and Prudhoe Bay sources. Currently, inflation has been constrained by punishingly high energy costs. The yearly average price for crude in 2008 was $90.89! This would imply short term rates of 15.25%.

Oil from a new North Sea or North Slope does not appear available, today. The current year (2009) average is a relatively inexpensive $42.91 for the first three months. What is troubling is the absence of the mention of energy anywhere in the public discussion. Outside of relatively obscure records of Fed policy making, it is difficult to find 'oil prices' or even 'interest rate increases' in statements or announcements by either the Federal Reserve, its officers or the Treasury. I will leave to others whether this absence is in the public interest.

A significant difference between the current crisis and recessions past has been the growth of and reliance upon structured finance. An "unintended consequence" is its demonstrated vulnerability to what has to be considered a routine increase in short-term interest rates.

The housing bubble and the follow-up 'petroleum bubble' illuminates one flaw--it works too well! It inflates asset prices to levels unsupportable by fundamentals. One reason for the 2008 oil price acceleration was the flow of funds or quantity of money' effect on the fuel market. The turnover or velocity of transactions in both the spot and futures markets by hedge funds and other structured finance participants had a large inflationary effect. As in housing, once the velocity of transactions slowed - due to unsupportable pump prices stifling demand - the inflating effect of the turnovers was removed and prices reversed.

I want to thank Steve Ludlum (aka Steve from Virginia) for the huge amount of work he put into this research. He tells me he has about 100 pages of backup, and I believe him. I think the connection between oil prices, the general inflation rate, and the Fed actions is an important one, and one that is easy to overlook.

Excellent post.

(I will reread it later).

One thing that caught my attention was that given the history plot of oil prices and funds rate (figure 4) they generally seems to have been moving in tandem until the most recent oil price spike when rates went down as the oil price headed for the sky.

I am just trying to get to grips with the significance of that.

Generally, an increase in oil (energy) prices does not cause inflation, but they act inflationary (according to the Austrian, Mises thinking). A rising oil price should then be met by an increase in funds rate to take out some of the inflationary pressure from rise in the oil (energy) price, which did not seem to happen this time (2007/2008). Volcker succeeded in his interest policies back in the 80’s and some have speculated in that the increase in interest (funds) rate helped bring down the oil price.

I am not an economist, so perhaps others among the readers have something valuable to add.

It seems like the Fed thought it could control inflation rates, and hence oil prices, by raising the interest rates. They really couldn't do this-they could just derail the economy (especially since their actions were in tandem with rising oil prices).

By the time oil prices were really high, the housing market (and for that matter, the rest of the financial system) had started tanking. There was no way that the Fed could bring down oil prices with higher interest rates because the formula they were using assumed that a really high interest rate would be needed to bring down the oil price, and all the economy could stand was practically 0%.

Unwinding credit eventually brought the price of oil down, but also brought the rest of the economy down.

Yeap -- credit is the problem here. A lot of its were concentrated in the housing sector made things worse. I think our economic model is all messed up. Sure, housing is important but it doesn't grow economy long term. People were investing in homes in order to sell later at a higher price. But economically, this investment doesn't add to the economy in the future -- it's like buying a TV.

If, instead, more investment in future energy and high efficient manufacturing/agriculture then we would fare a bit better when crisis comes. We got to make and create something to do useful things -- when a high percentage of your capital is going into "finance" and "service", it just doesn't really make a sustainable economy.

Inflation is defined by von Mises and the Austrian school as an increase in the supply of money.

The result of this increase in the supply of money is that each unit of money becomes less valuable.

As each unit of money comes to be recognized as less valuable all the users of money seek to raise their prices in order to retain the purchasing power of the prior dollar valuation.

So your proposed causal chain is incorrect. The correct form would be

increase in money supply -> increasing inflation -> lowered value of each dollar unit -> increasing price levels in an attempt to maintain purchasing power.

Credit is a form of money. Novel methods of structured finance and the associated financial products resulted in the creation of "near money" ie credit. The availabilty of cheap credit resulted in buyers bidding up the prices of all goods and services including the price of FF.

FF prices collapsed when the credit markets collapsed. The credit markets collapsed when the major banks realized that they were technically insolvent. The government has treated this insolvency problem as a "liquidity crisis." The insolvency problem remains unresolved.

Your thesis is as incorrect as the Gail thesis on which it is based.

BOP and Rune, initially I was going to say:

"you are confusing a straight economist view of the world with the real world we all have to live with. If it is now costing me more fill up my car or heat my home than it did previously, then I have suffered inflation, no matter that the money supply has not changed."

But then started to think about it and realised that following through von Mises does in fact support the thesis proposed here, rather than disprove it. In simple terms:

Higher prices (for energy)-> greater profits for holders (hedge funds) and sellers of energy (oil companies) -> increase in money supply -> increasing inflation -> lower value of each unit of currency -> increasing prices.

The issue, and ultimately the point that Steve/the oil drum is making, is that energy is so integral to our modern way of life that it can directly lead to inflation and can cause/assist economic growth and collapse.

I think you are right on this. The fact that the Fed was tracking oil prices, even when they were in the $20 to $40 range, by itself says a lot about the importance of oil prices and availability.

Further up I wrote:

A higher oil price does not automatically mean higher profits for hedge funds/oil companies. A higher oil price may be the cause of increased costs for producing oils.

When oil/energy prices increases the average consumer will experience a price increase. This price increase acts inflationary and may by the consumer be perceived as inflationary.

Inflation (according to the Austrian school) is caused by increase in the money supply. So if demand is higher than supply and money supplies increase => inflation results (lowering purchasing power of the money).

When the central bank increases interest rates it withdraws purchasing power from the market (credit becomes more expensive and more of the paycheck is allocated to entertain loans). The other way to reduce purchasing power for the consumer is by increasing taxes, which is highly unpopular.

This is what Volcker did back in the 80’s and if we had a diagram illustrating credit/debt in total or relative to GDP I would expect to see that these showed a downward trend in the US as interest rates went up.

The interesting this time is that there seems to have been a lot of money (debt and credit) in the economy chasing a commodity which demand was higher than supplies (oil) which sent the oil price to new highs.

If the central bank had increased interest rates earlier could that have taken out some of the demand and thus reduced the price of oil (and other energy)? and possibly delayed "Peak Oil"?

Rune et al -- the relationship between inflation and money supply didn’t grab me at first but y’all have me warming up to it now. Your statement re: higher oil prices don’t guarantee higher profits struck me in particular. I’m going to offer a summery of a ton of anecdotal evidence from my 35 yr career in the oil patch and see how you can integrate it into your developing picture. I won’t list the details but the summery is very solid. I recognized the detrimental affect of higher oil prices towards the bottom line of many companies I’ve dealt with over the years. In fact, at least 20 years ago I began explaining how the oil price spike of the late 70’s did more to destroy the oil patch then anything else I’ve witnessed. I see a similar analogy to the housing bubble and its bust with the drilling bubble of the long ago boom and, perhaps, what we’ve seen the last few years.

Simply: the price spike led to a rig count topping 4500 by 1980 or so….twice the max we just saw. I can promise you that at least half those rigs were drilling crap. Prospects that would not have been profitable at any price because nothing was found. But there was a silver lining to the situation also: existing production (which was developed using much lower prices) began generating huge cash flows (i.e. creating money). Unfortunately many of the companies took that CF, spent it and borrowed against its future value to drill many poor prospects (sounds a little like the logic that justified the sub prime boom). I still recall pricing platform which predicted oil prices above $80/bbl by 1986 (when prices actually dropped to $10/bbl). But it would not have made much difference to many operators had prices reached that level. A dry hole (drilled at very inflated costs) doesn’t make a profit at any price. Just as a spec home built at very inflated costs can’t be sold for a profit if you can’t sell it (i.e. foreclosure). Those high prices of the 70’s boom led to the ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips, etc of today. And a great many more companies disappeared as a result of the consolidation and contraction of the industry during the 80’s. I recall a statistic that the oil patch lost more jobs then the combined total suffered by the auto and steel industries in the US.

Perhaps it’s my personal experience that has caused such a pessimistic view of high price spikes not necessarily being good for the industry. In the mid 80’s, during the worst of times, I generated the most profitable drilling program during my career. Even though I sold NG from this shallow Texas play at prices between $0.90 and $1.25 per mcf I could drill and complete a typical well for $50,000 or less. In early 2008 the same well would have cost over $500,000.

I’ve rambled but I think y’all get my point. I’ll be very interested to see how your thoughts on how this story fits with your thoughts re: money supply/inflation. Those hedge funds and oil stocks which sold for such premiums less then 12 months ago stand as a testament to the ability of oil price hyperinflation to cripple the presumed beneficiaries.

And yes, if you were wondering, I’m dusting of a shallow oil horizontal redevelopment program in S Texas that wouldn’t work very well when oil prices were high. Between the high drilling costs and the ridiculously high amount I would have had to pay for to buy some of these old fields it just didn’t work. Now it’s has become a buyer’s market just as it did in 1986.

ROCKMAN,

You wrote,

I assume that you by this also means a well with (for all practical purposes) the same flow and recoverable reserves.

What you describe is a huge price (cost) increase for the well even adjusted for inflation. The price increase for just drilling the well tells me that the price of gas needs to go higher to make a profit.

Depending on what schools of economic one refers to, I would say that the higher costs from drilling would result in higher nat gas prices, but this need not be inflationary. It may be a reallocation of GDP between sectors in the economy. Most consumers will refer to it as inflation.

To me your story illustrates another interesting point, energy will have to go higher in price to become available. I think we are headed for this transition where energy will cost more, be less available and at the same time we could see the GDP shrink which suggest less money available for other sectors of the economy.

And yes I think it is true that high oil/nat gas prices could do more harm than good in allocating resources as you describes above.

Rune -- Yes...the same well with the same potential increased by at least 10 fold. But it was more then just inflation as we generally think of it. The $50k price represented a much deflated cost with the 2008 $500,000 cost representing a hyper inflated cost that really couldn't be justified if one were to use a conservative pricing forecast. During my career I've seen many wells drilled which, though they had low potential for profitability, they did offer companies the opportunity to meet Wall Street's demand for "activity and asset growth". In other words, the "sizzle". Thus I think my story actually argues, to a degree, that the potential for much higher prices to improve the supply picture is questionable. With respect to "the higher costs from drilling would result in higher nat gas prices" I wish that were true. NG and oil are sold based upon current market forces and not on the development costs. Much of the shale gas production is today selling for less then the cost to develop it. Chesapeake might have announced plans to cut production rather then sell at a loss but that generally isn't the rule. Most companies, especially the privately owned, must survive on cash flow. As long as the net income is positive many of these wells will continue to produce at max rate. In fact, it's not uncommon for operators to spend additional capital during low pricing periods to increase production.

Some folks have been forecasting deflation and its eventual damage to the economy. I hadn't been thinking in those terms re: oil and NG but that's exactly what we're seeing today. Really no difference then the deflation we've seen in the housing market. Some economists have argued that deflation has the potential to inflict more long term damage to growth then inflation. Too much macroeco for my background so I let others argue that point.

The one wild card I see in the equation today which wasn't there in the 80's is the shale gas potential which has been proven. There are 10's of thousands of proven viable NG wells that will be drilled when the prices recover to a supportable level. At this point most of the active players know what that price is. Just a guess on my part: $6 to $8 per mcf. But, just like in the 80's, the price spikes have led to a crippling of the energy industry. Even with this bank of proven assets and supportable prices I doubt we'll see a boom similar to what occurred in the last couple of years. Besides the loss of manpower, equipment and finance, the memory of the price collapse will be very fresh and will be part of the risk analysis. We've discussed here before what actions the gov't might try to avoid the boom/bust cycle. It's difficult to imagine the roller coaster not getting worse as resources continue to deplete and growth recovers in the world economies... especially in the energy exporting countries. I don't recall anyone formulating a viable approach to this end. We in the oil patch also won't hold our collective breaths waiting for bail out money for the oil industry. (Sarcasm alert): After all, it's not like we're too big to fail nor are we a vital component to the economy's future growth potential.

A lot of excellent points.

Unfortunately, finding funds after the current obsession with saving Wall Street fades away will be difficult. Trust is another resource that is becoming short of supply.

We are dealing with a constraint system so I somewhat see the reason for above.

Let say, 1000 years ago -- when farming was done with horses. A disease swept through and killed 1/2 of the horses. Those that survived will have more value as they play a critical part in people's lives -- no money is created and things get a bit more expensive -- so there is an inflation of sort.

We are living in the world -- where the governments really try to control this inflation. In their economic and business model, where growth is good and encouraged, it make sense to borrow now and payoff later. Thus encourage this unchecked supply of money flow. It's all dandy until they realized 1) "it's too much" and 2) "there is FF constraint" -- they can't keep adding more debt (credit is a form of debt) while realizing they can't really pay the darn thing in the future. So the collapse happened. For the current crisis, the credit was destroyed before the FF collapsed. So you can see which factor is more important.

It is not good that we keep running into old ideas that will impede us from understanding the core issue of the problem. Ideas/ideals of unfestered growth are gone --- we might be way pass the overshoot in term of "growth" and should start to think about "controlled decline".

One of the current conversations between Mr. Bernanke and his critics - including Paul Volcker, who was Fed Chairman during the inflationary recessions of the Carter period - is the idea of 'targeted interest rates' and an agreeable level of inflation.

The Fed and the rest of the finance system requires a certain level of inflation in order to reduce the real value of lending principals and to offset borrowing costs. How much inflation - and how to get some - is becoming controvercial.

This is from Mish, recently:

There is much more, of course in the economics blogs.

Another related issue is the matter of money supply expansion and how it all relates to structured finance:

UPDATE: Fed's Yellen Says Policy May Have To Pop Asset Bubbles

Yellen is a sitting Fed Governor, so what she's saying is 'official policy' ... a re- direction of Fed policy and perhaps a desire to create some new tools. One of the interesting questions that hasn't surfaced yet is what sort of fiscal tools might have directly addressed the energy component of price increases (acknowledging that by themselves price increases are not necessarily inflationary but for the Fed's purposes were an indicator). Reading between the lines it is clear that the Fed is aware - now - of the effect of its 'Blunt tool'.

What is ironic is ... at the same time as Yellen's remarks Goldman Sachs and a few other Wall Street market makers are inflating an asset price bubble right under the Fed's nose! With Fed liquidity (Goldman is a 'Bank', now) and Treasury (taxpayer) funds, no less.

Thursday, April 23, 2009

Goldman Sachs Principal Transactions Update: 1 Billion Shares!

Basically, Goldman is trading the same fifty thousand shares, back and forth, over and over and over with counterparties (Credit Suisse, Morgan, Merrill, etc.) driving up share prices in the process.

If anyone is curious about this I recommend

Zero Hedge.

Edit by Gail For some reason the image isn't showing up for me, but the code seems to be right. It is not showing up, this is a link.

Actually, a disease did kill off most of the horses in the US around 1857. Men had to pull wagons through the cities to deliver goods. It is said that this was a factor in the Panic of 1857.

Actually, I think the thesis is correct (or at least a major part of the problem) - good analysis Steve.

Steve is looking at the situation from a USA centric point of view because that is where he can find good data.

I look at the situation from the world point of view. The recession is not just in the USA it is worldwide so the cause must be worldwide too - every nation must experience the same dislocation - most nations do not have the crazy US/UK banking systems.

Oil is a very good candidate as a cause since it is fungible and is embedded in so many things - like food (10 calories of oil for 1 of food), any mined substance, anything manufactured etc etc.

But, most importantly, we don't have available adequate alternatives to oil on a short term basis, so we have no option but to pay the price if we have started to base our lifestlyes around its use.

When the crude price rises from ~$10 in 1999 to ~$150 in 2008 the increase in money supply needed to pay for the essential commodity rose ~1400% - I would submit that that is massive hyper-inflation (and a massive loss of money to spend on anything else discretionary, like a new house or car - otherwise known as a recession.)

BOP -

I am admittedly in over my head when it comes to some of these economic discussions, but I am having a bit of difficulty seeing a direct causal relationship between rising oil prices and inflation. My train of though is along the following lines. To keep things simple I will confine it solely to consumer spending.

1) Consuming spending on fossil fuels is largely non-discretionary. One needs to drive to and from work and to the store to buy key necessities, and while one can car pool and consolidate shopping trips, there is a certain core amount of fossil fuel that will have to be purchased almost regardless of price.

2) On the individual level, consumer spending is largely a zero-sum game, particularly for people highly dependent on earned income. In other words, the extra twenty dollars a week I must spend on gasoline is twenty dollars that I won't be able to spend elsewhere. While Exxon Mobil may receive twenty dollars additional income, my local restaurant may receive twenty dollars less income. One sector of the economy benefits while the other gets hurt.

3) Unless I take on additional debt to maintain my former level of non-energy purchases, a rise in oil prices does not necessarily increase my total household expenditures: it just rearranges them. Hence, high oil prices in and of itself does not cause me to circulate more money through the economy. As long as I don't increase the amount of debt I take on, my contribution to increasing the money supply should essentially be zero.

4) Could it be argued that high oil prices might even have a deflationary pull? To use a crude mechanical metaphor, high oil prices could be viewed as the introduction of more internal friction to a complex machine, in that the machine becomes less capable of producing its former output and thus becomes less efficient. The high oil prices become a drag on the economy, causing decreased output in non-energy sectors, stagnant wages, and less consumer purchasing power. Unless a worker can demand and get a pay raise on the basis of his/her increased gasoline expenditures (fat chance!), that worker will not be spending any more of his total income than before and hence will not be contributing to inflation.

Does this line of reasoning make sense, or am I missing something very basic here? Please feel free to take a whack at it.

I learned to type with two fingers on the original Prodigy a couple of decades ago. This was during the early Compuserve AOL days. I recall once stating that a rise in oil prices would not necessarily lead to inflation as it would tend to siphon dollars away from gasoline users. They would then have less money to spend on other goods. This might cause some prices to decrease. I was told in no uncertain terms that I was an idiot who knew nothing about economics. This was perhaps true. I had never had a formal course in economics and was, at about the same time, trying to understand Fractional Reserve Banking - with less than total success.

I think there are several things going on simultaneously.

One is the point you are talking about, which is the higher gasoline and food prices having an impact people's ability to purchase other things. One of the problems is that the higher food and oil prices cut back on discretionary spending, for things like restaurants and books. These restaurants and stores had loans outstanding. With less income, they became less able to pay their loans back. That is one of the reasons we are running into problems with bankruptcies and loan defaults for these types of business. It didn't really matter that the oil companies in Canada or Mexico or whatever country we were buying the oil from had more money.

Another problem is with the higher oil and food prices, some people defaulted on their home loans. Initially, this tended to be people with subprime mortgages, since these were people with least cash to spare.

An indirect impact of the higher food and oil prices was that people had less to spend when they purchased homes, so the demand for home started going down (particularly in the more distant suburbs).

Another thing that was going on was the Federal Reserve, adjusting interest rates, trying to get inflation (really oil prices) down, that Steve is writing about in this post. The Federal Reserve raised target short term interest rates, which makes short term rates for things like home improvement loans higher, and variable rate home loans higher. The higher target interest rates also made it much less profitable for banks (and other lenders borrowing short and lending long) to issue mortgages. In fact, some of their old mortgages probably became unprofitable, because of the higher interest rates. As a result, people were being charged more for home improvement loans and second mortgages, adding to the burden of the higher food and oil prices.

The combination of both of these things started bringing down home prices - people not being able to pay the price any more, and mortgage sellers having trouble with the higher short term interest rates. The higher default rates also made banks more leery of writing loans, and those buying structured securities leery of taking the risk.

Bringing down home prices had huge indirect effects. People had been counting on their homes to act as "piggy banks". Each year, they would refinance, and take more equity out. This equity could be used to buy more "stuff" to stimulate the economy. One the price of homes started going down, they could no longer buy more "stuff", and this source of stimulation of the economy went away. Furthermore, when they went to sell their homes, they often found the mortgage was for more than the value of their home, causing loan defaults, or the need for a "short sale".

All of this contributes to the mess we are in now. In order to pay back loans with interest, we need to have a growing economy--in other words, to borrow from the future, the future has to be better than today. Without a constantly growing oil supply at low prices, this necessary growth starts to go away. As soon as the future is the same, or worse, that today, the whole debt-based model of financing starts to fall apart, and you get to the place we are today.

It's (painfully) interesting to read the minutes 2006-2007 because they illuminate the decline of housing, this includes exactly what Gail has mentioned.

In fact the Fed was discussing the effects of petroleum prices on consumer spending in 2004:

The governors make an attempt to gauge the expectations of the public so as to anticipate what sorts of pressures they will deal with in the future.

Another real estate related issue that Gail and I discussed was the effect of rising rates on the types of mortgage that rates and the financial system made available. For instance, a conventional 30 year loan @ 5.5% is unprofitable for securitization when short term money cost is 5%. An old fashioned originate- and- hold mortgage would be barely profitable to a Savings and Loan but the lender would derive other banking business from the borrower. With the older model, the bank and the borrower were part of the same community.

With securitization, the homebuilders, banks and mortgage brokers steered customers into high- yield (or subprime) loans @ 10% and more. These loans were profitable to the lenders. Speculators also borrowed subprime because no documentation was required. The costly loans were more difficult to service, the lack of equity (no money down! No closing costs!) left owners with no refinancing option and defaults accelerated. All the factors started feeding on each other in a vicious cycle.

A large question is why wasn't the Fed more prepared? There have been many oil shocks, this isn't the first. Also, Greenspan dealt with a similar meltdown of Long Term Capital Management in 1998. Why didn't the Fed have a better plan to deal with the sectors vulnerable to interest rates?

Gail -

Thanks much for the clarification.

I am not doubting in any way that high oil prices have seriously messed up our economy. They have for sure. You quite correctly point out that people/businesses that were in a somewhat fragile state before the spike in oil prices have now been pushed further into dangerous territory as a result of the price increases. Hence the increase in foreclosures and bankruptcies.

As I alluded to, the increase in oil prices has acted as a serious drag on the overall economy, as we have to pay more to do what we were doing before the price spike. Hence a shift of income from multiple sectors to the energy sector. We are getting less able to leverage energy expenditures into economic output.

I can see this as a cause for a drop in overall standard of living, but I still have a hard time seeing rising oil prices as directly causing monetary inflation.

Perhaps this gets to the very definition of inflation. In some people's view, any price increase is by definition, inflation. Others claim that inflation can only occur if the supply of money is artificially increased. I tend to agree with the latter point of view. In a famine situation grain prices will rapidly spike, but that is not the same thing as the ruler of the land printing more money so he can fight some foreign war. I view the former as simple supply and demand, and the latter as an example of true inflation.

Anyway, I find this a fascinating topic.

The problem with rising oil prices is that they tend to result in rising energy prices of all kinds - gasoline, diesel, natural gas, coal, electricity, because all electricity prices are to some extent substitutes for the others. Food uses a lot of oil in its production and distribution, so its cost tends to rise as well. The cost of shipping anything rises, as does the cost of air travel. Because of these issue, a little bit of oil inflation thus spreads around to a lot more, just considering this issue (and not the disruption to the loan repayment system and other secondary effects.)

Exactly.

This is how my simple mind defines inflation:

Prices rise, purchasing power decreases.

Since oil is the lowest common denominator in our economic equation, if oil prices rise, so does the price of everything else, thereby reducing the value of a dollar.

Some claim that inflating prices will result in higher wages but I have never experienced this, rather inflation causes high employment, like it is doing now and like it did in the'70's.

Of course if dollars became readily available, e.g. BO gave everybody a million bucks, I can imagine inflation would rage since goods would command higher prices.

In regards to Peak Oil or rather the downslope, as the amount of oil becomes constrained we can expect to see the price of oil to rise uncontrollably, IOW hyperinflation.

Not there yet but soon.

Your statements in the para above are correct. Your application of this knowledge to the current financial problems is however completely wrong and utterly misleading.

Elsewhere on TOD Hamilton tries to establish a link between rising FF prices and the housing collapse. In summary form the thesis is that the global financial crisis is a direct consequence of increasing FF costs and the impact of these costs on economic activity. I refer to this as the "Gail Thesis" as it first appeared in one of her articles.

I do not dispute that FF prices have a significant impact on all other price levels. This effect was most clearly seen during the 1970's OPEC embargo. However, since that time the ratio between a bbl of oil consumed and a dollar of GDP has changed significantly within the US. The US is less energy intensive than it was in the 1970's. The same bbl of oil now produces approximately 25% more GDP than it did 40 years ago. Some 20% of US GDP now derives from financial activities and running a bank does not require the same energy inputs as running a steel mill. At the recent peak of $147 a bbl oil prices were still below the 1970s peak price on an inflation adjusted basis.

Gail, Hamilton and Steve are all conflating two distinct issues. The first issue is the relationship between economic output and the amount of FF required to produce that output. The second issue surrounds providing an explanation for the current financial problems and grounding the explanation of those problems in a FF price rise.

Housing peaked in the US around 2005. FF prices peaked in 2007. How does a cause have explanatory effect if it arrives after the phenomenon that it is intended to explain?

Oil prices have declined but there has been no corresponding economic recovery. My belief is that the situation will continue to worsen. Part of the reason for this is that the Fed is treating the wrong cause (they are responding as if the issue were a liquidity crisis rather than an insolvent financial system). An excellent article in the NYT gives another reason:

Norris provides a succinct summary of the cause of the problem:

"How did we get into this mess? The story is remarkably similar to the tale of subprime mortgages. Lenders who were making money by putting the loans into pools became more and more eager to make loans, and less and less concerned about their quality."

The issue is not that a rise in FF caused folks to default on their mortgages leading to a global credit crisis. The cause is the inappropriate extension of credit to people who should not have had that credit in the first place because they did not have the means to service the debt load irregardless of the future price of FF.

Gail et al would have you look at a drowning man and have you believe that the reason that he is drowning is that he put some pebbles in his pockets. Because he is now overstretched and unable to support this increase in weight he is drowning and taking the global financial system down at the same time.

My argument is that the man is drowning because he cannot swim. He should therefore never have gone into the water in the first place. The pebbles in his pocket are irrelevant to his death.

Another poster makes the claim that FF must be the cause as the impact is global and FF markets are also global. This disregards the degree to which the world financial system is today a fairly tightly coupled, highly integrated system (see Wallerstein for a theoretical overview). Shocks in one part of the system will have an impact in other parts of the system. I would argue that the system is sufficiently complex that no one has a full understanding of its workings and we can expected the law of unintended consequences to be at play.

Joule - you are correct that transport costs are non-discretionary. However the availability of cheap credit encouraged folks to buy more house than they could afford. One means of increasing affordability is to accept a long commute. So if you look at a timeline you see something along the lines of:

1) cheap credit;

2) urban renter uses cheap credit to purchase suburban dwelling on which he cannot service the debt [he buys at a teaser rate with a reset to market after two years plus he avails himself of negative amortization in which his interest costs are added to his principal, plus he buys in a market which has already undergone frothy appreciation and is being called as a bubble as early as 2004-2005];

3) housing market collapses. This takes place as it was fundamentally a ponzi scheme which depended on a continuing stream of fools. Once the supply of fools dried up the market collapsed; 4) all the players in this market now find that their leverage of 40 to 1 is working against them, the the MBS and CDS and CDOs and all the rest of the jargon financial products are not as originally advertised. Since financial markets are global the impact is global in scope. The credit markets seize up as the players realize the distinct possibility that they are technically insolvent or that their counter parties are technically insolvent; 5) Gail et al observe this and declare that the man is drowning because he cannot afford the weight of the two pebbles in his pockets.

Even were the man to remove the two pebbles form his pockets he will still drown because he cannot swim. Even worse, he is going to drown because the people on shore are shouting at him to take the pebbles out of his pockets as they fail to properly recognize the true cause of his distress.

The basic issue is that one cannot borrow from the future, unless the future is better than the world is today. I have expressed this statement in many ways. One is that with our economic system, one needs growth in order to pay back debt with interest. As peak oil hits its plateau, and many other resources become constrained, we cannot grow as fast as in the past. It is really this lack of resource growth--which does not even have to be decline--that is the underlying factor in our current financial problems, and that we expect will exert a huge squeezing impact on the economy, more and more as time goes on.

The sub-issue is whether there is a some causation between the rise in fossil fuel prices and 2006 housing collapse. We at this point know a whole lot of links which seem to indicate that this is the case, some of which I enumerate below. Whether or not there is a link is really only a nice-to-know piece of the total story, since the basic cause and effect has nothing to do with whether there is a connection between fossil fuel prices and 2006 housing collapse. Because of the basic relationship, we would expect that there would be pressure in this direction.

Three of the connections between FF and 2006 housing price collapse:

1. Higher gasoline prices reduced the amount people had available to spend on other things. People no longer wanted to live in the most distant suburbs. The most vulnerable (subprime mortgages, distant suburbs) started defaulting on their debt. For examples, see Fuel Prices Shift Math for Life in Far Suburbs.

2. As Steve documents in this post, the Fed based their decisions on whether to raise interest rates on whether the price of petroleum was increasing. The higher interest rates they chose to use (to damp down the price of oil, which they knew would tend to send the economy into recession if it continued to rise) had the unintended impact of destabilizing the financial system, which needed a bigger spread between mortgage rates and short term interest rates to be profitable to banks.

3. The decline in per capita miles driven occurred at precisely the time of the price drop started in the more distant suburbs, according to this Brookings Institution report

This is also incorrect and represents a multiplicity of misunderstandings

If you engage in making and selling buggy whips and horse harness at a time when others are introducing automobiles then you may expect your future to be constrained. Your firm will likely fail while at the same time the emergent automobile industry grows.

If you engage in making and selling ICE automobiles at a time of growing resource constraints then you may expect your future to be constrained. The future for competing firms providing other technologies may be bright and they will experience growth and be able to make debt payments while the ICE automotive sector collapses.

Your claim with regard to future resource constraints may be true. But this does not prevent the introduction of novel technologies and different modes of life. The best of these alternates will likely be very profitable and they will experience growth.

This is also incorrect.

If you are speaking of FF then the problem is that we have been borrowing from the past, ot the future. That cannot continue.

If you are speaking more generally then I would argue you have misinterpreted human history.

The crux of the issue is what you do with whatever you borrow. If you invest your borrowings in a manner that will benefit future generations then you have added to the stock of physical and human capital. Borrowed funds invested in railway alignments in the past continue to provide benefits to society today. If you do not agree, argue with Alan.

If you take borrowed funds and spend those funds on killing Muslims, on military adventures in foreign lands, on maintaining an empire, on consumer products, entertainment and video games then you have destroyed wealth that rightfully belongs to future generations. You will have impoverished your children and loaded them with an impossible debt. Think of the what the billions of bail out dollars might have achieved if those funds were invested in improving the quality of secondary education. America continues to obsess over the quality of the Chinese military; what you should really obsess about is the quality of Chinese education.

If the future does not hold the possibility of a better world then why do you bother with TOD? What is the point? Why spend the effort? The reason you exert yourself is because you DO believe there is some possibility of positive change. And if you acknowledge that belief that then it throws your entire thesis into question.

Nobody is going to deny that improper underwriting had and still has a large effect on business activity. The effects of energy prices on household budgets during the spike was pretty severe for a lot of people. All of those consumer choices ricocheted through the rest of the economy. Peoples' re- allocating funds from one priority to the next certainly had an effect on retail, for instance and imports that support retail, and the advertising and management that supports retail as well.

The problem, as you note, begin when you move from the retail level and upstream support to the finance/macroeconomic level. Your - and many others as well - indictment of underwriting is apt, but doesn't explain systemic failure. Keep in mind that at the point of underwriting, all these loans were good loans. In the words of Mae West, "I was Snow White ... but I drifted." Now, even the highest quality lending is falling into the 'bad loan' category. Poor policy is a reason and the multiplier of leverage working in reverse is another amplifier.

So the question is what precipitated the turn from good loans to bad? What we can call the 'Norris' theory holds that all those loans sucked from the get-go and nobody in their right minds should have made them in the first place! Okay, I don't have a problem with that ... except these were all good - marketable and collectible - loans at some point in their lives, back in 2002 - 2004. Why not make the good loans? Why leave money on the table? If Company 'A' had not made these loans, Company 'B' or Company 'C' certainly would have done so.

A change in interest rates can also precipitate good lending into bad. That's what started this investigation. There is very little comment in the media or elsewhere of the effects of interest rates and what caused them to rise.

Another characteristic of our crisis is that it is credit driven rather than an inventory/asset driven as in 1999- 2000. There has been no serious Fed tightening since the early 1980's. It is likely that most participants in the current lending cycle were not old enough to experience first hand the effects of serious tightening on a credit driven economy.

With this question it is more about pushing costs into the future (and letting our grandchildren clean up the mess.) Gail's question is,"Where will this money come from?" Borrowed, certainly ... so that the illusions of solvency today can be conjured out of certain ruin in the future since the lenders of the future cannot deny the loan, they can only refuse to repay it!

What sort of future is this? It's not so much a positive change swimming against the tide back to us and helping us out of our current predicament, it more convincing ourselves our habits - and the excuses for them - are inevitable. We hedge our bets and hedge and hedge and hedge some more in a daisy chain and then, congratulate ourselves for our cleverness not realizing our hedges have sold the floorboards out from under our feet. This is where this particular dialog goes. It is avoiding a choice and pretending it's not there.

Petroleum lobbyists claiming that pollution controls will put Americans back into the Stone Age. One follows the other very logically, as in step one then step two.

The only way ... the only absolutely positive way ... for us to escape this corner we have painted ourselves into is to be ruthlessly honest with ourselves and act ruthlessly on that truth.

Cleveland, Hall and Kaufman have an extensive discussion of inflation vs energy in the book Energy and Resource Quality.

They have a brief discussion in this paper Energy and the United States economy: a biophysical perspective

I think we can all agree that if money is printed (or loaned into existence) faster than the economy creates goods and services, that inflation happens (the money becomes worth less). Which is what I feel we saw in the housing market. Money flooded in faster than houses could be built and prices tripled in 5 years. Conversely, if money is printed slower than goods and services are created than deflation happens, as each dollar represents more goods and services (and we run the risk of a credit crunch as people horde currency).

What the graph above is saying is that the money supply divided by quality adjusted energy entering the economy predicts inflation. This makes really good sense, because energy is the ability of the economy to do work. And money is a demand for work on the economy (when I push my stored dollars across the shop counter I am demanding work be done on my behalf). These two *should* be tightly correlated.

Notice that it does not matter if your currency is gold, or paper, or sea shells. Energy is the true currency and the goal of the central bank is to get the token currency to match the rate that energy enters the economy.

So what happens when the supply of oil is suddenly constrained?

The economy should contract, as it cannot do as much work as it used to be able to do. And if the money supply is loaned into existence at a faster rate, then inflation should happen.

If the Fed decreases the interest rate and loans more money, we should see higher inflation.

If the Fed increases the interest rate and loans less money, we should see inflation moderate.

I feel that the energy supply hitting peak in coal and natural gas in the US caused the economy to stop growing in physical terms. The Fed tried to increase growth by loaning out more money. That created the housing bubble. Then the Fed was trapped. If it increased interest rates and reduced the money supply, the banks would fail. If it didn't increase interest rates the currency would inflate.

So what happens going forward? Are we doomed to a series of bubbles and bank busts as the amount of currency in circulation is forced to contract to match the shrinking real economy?

Almost all alternative energy systems (and nuclear power assuming there is enough uranium) depend on up front loans to finance the whole project. They are going to be punished by high loan rates as the Fed tries to control the money supply. How can we keep investing in the energy sources we need most? I think a special loan program will need to be setup to continue investment in a declining environment.

Thanks for the link, very interesting article. Herman Daly - among others - has come to basically the same conclusions.

A very interesting article. But it was 1984. The recovery from the 1982 / 1983 recession is usefully discussed in the article's concluding remarks. The assumption then of resource constraints and EROI appear somewhat more relevant 25 years later. The USA in particular managed to buy enough (increasing amounts of) external oil over the intervening 25 years to keep the US model growing, albeit with some strange unstable distortions. Dramatic increase in fragility of the economic / financial position of the US middle-class 'mom-dad-2kids', could be a significant systemic change, for example. Changes in the world economy (China digging out a lot of coal by hand, perhaps? the EU getting natural gas?) have kind of 'helped', but provide no long term strategy. The sophisticated financial instruments that kept this conjuring act on the road, seem to have run out of .. er .. road.

Took 25 years, but have we got there yet in terms of the 1984 article?

Fabulous post. Exceptionally easy to follow.

I'm not an economist, so I'm not bound by econothink. If oil costs more, eventually, so will everything else. (Don't bother replying to that; it won't get past the blood/brain barrier.) This was pretty clear from the quotes in the article. One comment directly stated the relationship of a rise in oil prices bleeding directly into CPI. My anti-econothink brain already knew this, and I have stated it a number of times, so no surprise.

What really strikes me is that they knew all this was coming - and lied about it. Remember all the, "Nobody could have predicted this" protestations of last Sept. - Nov.? Then we got the pseudo-admission that they had started planning "weeks and months" before the crash.

Well, turns out it was in mid-2006!! Two years before it fell apart!

Lying sacks of ____.

Cheers

Will Rogers said in the last Great Depression (which really was a GREAT...not good, but in scale great) "All I know is what I read in the papers"

For most of us, if you add the TV and the I-net blogs and boards, we are still in the same shape.

If all I know is what I read in the papers and media, then the world is gone to hell in a handbasket, it's all over, the gigs up.

But out here at street level, not much has changed IF you have kept your job (and most folks have so far)...Bloomberg reports that house prices has again started to rise...but in many areas they never even fell, they just slowed in the astronomical race to infinity. I have given up on a house for now, and will probably just stay in my tiny cell of an apartment. The prices in my area (central Kentucky) are still idiotic for anything in a decent location (meaning one that you don't have to drive for an hour and a half to even get to the nearest hospital or restuarant)and most of the south/midwest regions are in the same shape.

Gasoline is at $1.99 here and people are howling that's insanely high, it should come down! How quickly we forget.

Grocery and restaurant prices, which supposedly shot up because of oil prices when oil was $140 a barrel, have not come down because oil prices dropped back in the $40's. Why am I not surprised?

If could have afforded to buy more stock in the 3 companies I favored, I would haved almost tripled my money, plus 10% ongoing yield. But without the "opportunity money needed, I had to watch the big boys make a killing as they whined about about the economy.

Why am I not surprised by this?

Nothing surprises me these days. "The rich make money and the poor make babies." Life goes on as before unless you die.

RC

Huh?

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB124048949462047743.html

And just in case that wasn't bad enough:

http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/09_18/b4129028108940.htm?ch...

Cheers

So Roger,

Not sure what planet you're living on...

"...house prices has again started to rise...but in many areas they never even fell, they just slowed in the astronomical race to infinity."

I know you're good with numbers but I would double-check those 'starting to rise' claims. There's just no way and no how.

What are your 3 stocks? Tell us and we'll bid the price up and you can make even more money...

Zippy the Pinhead said "Life is a blur of meat and republicans".

"What are your 3 stocks? Tell us and we'll bid the price up and you can make even more money..."

SNV (Synovus Corp). up and down but from the original buy price I had recommended to friends, you could have sold off at 4.65 or better

APU (Amerigas Partner LP) (a killer, I recommended it to co-workers during the "big one week crash...already up a third with divy yeild of some 8% now, about 10% if you bought near bottom of 17.98 or less. But it's not fair to pick the bottom after the fact, my buy signal was set at 23.00 to buy and stay for the cash distibution, then over 11%, now at a paltry 8.20% on a price over 31 dollars.

LGCY (Legacy Reserves LP Partners), an oil and gas partnership) if you did it right you could have made a killing about anywhere in the band if you simply set your buy price and your target price at the same time.

RBCAA (Republic Bancorp)a central Kentucky bank, we folks in Hardin county who follow it have nicknamed it "The Bank Of The Gods". I owned back in the days just after 9-11-01, bought it at 8 bucks solde at about 14 because I thought it was out of steam. Folks I know who still own it now say "banking crisis, where?" Cited as one of the 10 best service banks in America, it is still loaning money, still funding KY development, and still going strong.

And a spare alternative energy play, VLNC (Valence Corp.) maker of large format lithium ion batteries, I recommended to a friend that she buy at about $1.30 (she did) and sell for anything over $4.00 (she didn't!), but she is still up almost double her money, could have been easily over triple and a half, right through the heart of the worst economic catastrophe of the post war era.

This summer, as almost always in the dead heat of summer, there will be a seasonal lull in stock prices. This will be one last chance to get in on 4 stocks you can probably sit on the rest of your natural life if your a baby boomer, with a good mix of income and appreciation. That's only my favorite four. There are hundreds more out there that will do as well or better.

RC

Go to this link, done on MSN giving last years "decline" in home prices. Take out the worst 10 markets. What you will see is a marginal decline at most, and this focused in the overpriced sunbelt and Michigan, and a few very pricy areas in New England.

http://articles.moneycentral.msn.com/Banking/HomebuyingGuide/HomePricesB...

In my area, which is Louisville metro and Hardin county, I have not been able to find ANYTHING reasonable that is not in a tiny town 70 miles from anything, or in drug infested crime ridden gang controlled areas of the cities.

I have done the calculations. I could afford to pay $5.00 per gallon and in any decent car could drive 60 miles per day, or rent an apartment, and never even match what the interest would cost on the decent homes in decent neigborhoods for the rest of my life, never mind the principle.

I found about a half dozen links on the story of home prices rising, but they all pretty much mirror the Boston Globe article:

http://www.boston.com/realestate/news/blogs/renow/2009/04/home_prices_up...

If this is true (and again, all I can know is what I read in the papers and the prices I get when I shop for a house), then at least in a great deal of the country, the home price collapse has been mostly home price hysteria.

RC

ThatsItImout:

I am in agreement with your observation. The mainstream media does not tell the whole story.

Real estate is local, and many cities with good economies that did not experience a boom also escaped the bust. I lived in a nice, close in neighborhood in northeast Atlanta, GA, selling out to retire elsewhere in late 2006. Prices continued to rise in my old neighborhood and only came down slightly in recent months. There are parts of the Atlanta area that have high foreclosures, mostly in distant suburbs, some hard hit by the closing of local Ford and General Motors plants. However, prices didn’t collapse, they just declined. The economy is well diversified and new businesses continue to move in.

A couple of unrelated notes. First, it seems to me that the fact this debate can even happen is proof that economics in its present state is clearly not a science, despite what any block of Austrians, Fed Bankers, or anyone else would like us to believe. Until some(one/group) of logical thinkers with access to all facts can sit down and develop a genuine science of economics, I'll continue to consider all economists more like magicians and priests than logical thinkers.

Second I was happy to see someone else note the "government's incentive to inflation" item above. I've long wondered why we voters continue to allow governments to publicly declare goals of "2% inflation" when it seems to me baldly obvious that 0% inflation, worst case a balanced plus / minus about the 0%, should be what is required. Agreed, a "survivable" inflation rate has the effect of eventually removing wealth from people who've accumulated it and no longe put it to productive use, but there are a variety of better and less dmaaging alternative means for that. I realize that governments see inflation as a means to devalue past debts, but we simply should not allow that, it being unethical. Worst, an expected inflation rate leads to the most insidious flaw in the present system, that of "automatic wage increases" unrelated to productivity improvements among wage earners, which in fact is a core contributer to many of our current problems. To me, part of the problem is that once all the wage-earners in a company are accustomed to increasing wages without increasing productivity then the executives become free to do the same and no-one questions, leading to the present insane executive comp. situation.

Of course, much more complexity involved.....

To summarize: When the energy available went down we needed to reduce total production AND reduce the proportion of consumer spending (in order to increase the proportion in investing in changing infrastructure). Instead we've had an attempt to keep BAU going. Indeed people with jobs and mortgages are BETTER off, with reduced mortgage payments and reduced petrol and other energy prices. This can't work. Latvia (or was it Lithuania) did exactly the right thing when they reduced all salaries by 15%. We continue to wait to hear some leader somewhere say: "We are all poorer because of the declining amount of cheap energy. We need to share that pain fairly in society. We need to go further and reduce spending on consumer items so that we can make a massive investment in changing infrastructure."

Actually OECD governments do get PO, they just recharacterize it as being about energy security and energy price. Basically this is a way of saying that on the down side of the slope they expect their country to be able to pay for an increasing share. We can see how that will happen. When the price was high last year we saw images on the news of diesel fishing vessels unused in Malayasia. The reason is that they can only sell their fish cheaply because their customers are poor. So when the price of diesel got high they couldn't justify using it to fish. In the west demand destruction was vacation driving, in poorer countries it can cut into core activities.

The long term correlation between money supply and a broad-based measure of prices (e.g. CPI) is close to 1.0, meaning that almost all of the change in prices can be explained by the size of the money supply. Therefore, printing money equals higher prices.

The US was on the gold standard for most of the period form the founding until 1933. Prices persistently declined during most of the 19th Century with exceptions such as the Civil War. This was due to increases in productivity first because of canals and light industry, and later railroads, steam powered factories and early petroleum and chemical industries. From the late 1800’s to WWI, prices declined about 1 to 1-1/2% annually. The Federal Reserve act passed in 1913, the same year as the 16th Amendment to the Constitution (income tax) was ratified.