Excerpts from "Energy, Growth, and Sustainability: Five Propositions" by Steve Sorrel

Posted by Gail the Actuary on April 19, 2010 - 10:18am

Steve Sorrel, Senior Fellow, Sussex Energy Group, University of Sussex in the UK has recently published a 25 page paper called Energy, Growth and Sustainability which can be downloaded at this link. This post provides some excerpts from the paper, which summarize its findings. Readers are encouraged to read the entire paper.

According to the introduction to the paper:

This paper questions the conventional wisdom underlying climate policy and argues that some long-standing and fundamental questions regarding energy, growth, and sustainability need to be reopened. It does so by advancing the following propositions:

1. The rebound effects from energy efficiency improvements are significant and limit the potential for decoupling energy consumption from economic growth.

2. The contribution of energy to productivity improvements and economic growth has been greatly underestimated.

3. The pursuit of improved efficiency needs to be complemented by an ethic of ‘sufficiency’.

4. Sustainability is incompatible with continued economic growth in rich countries.

5. A zero-growth economy is incompatible with a debt-based monetary system.

These propositions run counter to conventional wisdom and highlight either blind spots or taboo subjects that deserve closer scrutiny. While accepting one proposition reinforces the case for accepting the next, the former is neither necessary nor sufficient for the latter.

1. Rebound effects are significant and limit the potential for decoupling energy consumption from economic growth

This is basically Jevons' paradox, which has been discussed quite a few times on The Oil Drum. As technology increases the efficiency with which a resource is used, use of the resource tends not to decline as predicted. Instead, there tends to be a rebound effect, and the amount of the resource used may even increase instead. The section concludes:

In sum, rebound effects will make energy efficiency improvements less effective in reducing overall energy consumption than is commonly assumed. This could limit the potential for decoupling, although by precisely how much remains unclear. In principle, increases in energy prices should reduce the magnitude of such effects by offsetting the cost reductions from improved energy efficiency. This leads to the policy recommendation of raising energy prices through either carbon taxation or emissions trading schemes. Price increases will induce substitution and technical change , but their impact on total factor productivity and economic growth remains disputed (Jorgensen, 1984; Sorrell and Dimitropoulos, 2007c). This leads to the second proposition, discussed below.

2. The contribution of energy to productivity improvements and economic growth has been greatly underestimated

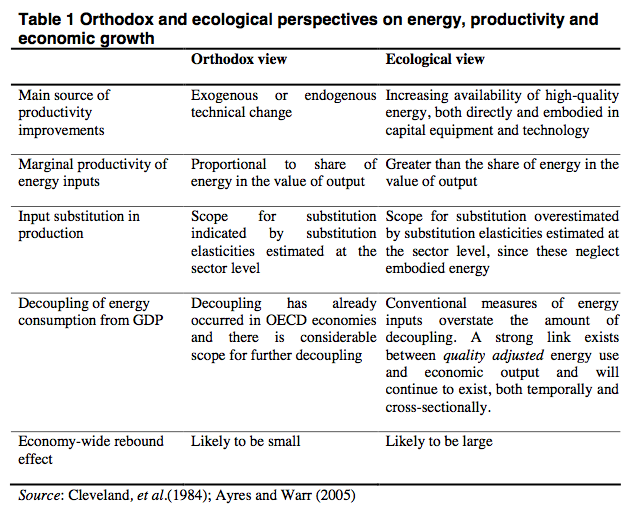

Many of the arguments in favour of Jevons Paradox focus on the source of productivity improvements and the relationship between energy consumption and economic growth. Orthodox and ecological economics provide very different perspectives on this question with correspondingly different conclusions on the potential for decoupling.

Orthodox economic models imply that the economy is a closed system within which goods are produced by capital and labour and exchanged between consumers and firms. While such models can be extended to include natural resources, ecosystem services and wastes, these remain secondary concerns at best. Economic growth is assumed to derive from a combination of increased capital and labour inputs, changes in the quality of those inputs (e.g. better educated workers) and technical change (Barro and Sala-I-Martin, 1995; Jones, 2001). Both increases in energy inputs and improvements in energy productivity are assumed to make only a minor contribution to economic growth, largely because energy accounts for only a small share (typically <5%) of total input costs. It is also assumed that capital and labour will substitute for energy should it become more expensive. From this perspective, improvements in energy efficiency are unlikely to have a significant impact on overall productivity, so the corresponding rebound effects should be relatively small. Hence, there seems to be no reason why energy consumption could not be substantially decoupled from economic growth.

Ecological economists consider that the orthodox models ignore how economic activity is sustained by flows of high quality energy and materials which are then returned to the environment in the form of waste and low temperature heat. The system is driven by solar energy, both directly and embodied in fossil fuels, and since energy cannot be produced or recycled it forms the primary input into economic production. In contrast, labour and capital represent intermediate inputs since they cannot be produced or maintained without energy. So far from being a secondary concern, energy becomes the main focus of attention.

Ecological economists claim that the massive improvements in labour productivity over the last century have largely been achieved by providing workers with increasing quantities of high quality energy, both directly and indirectly as embodied in capital equipment and technology . . .

Ecological economists also claim that the indirect energy consumption associated with capital and labour (e.g. the energy required to manufacture thermal insulation) limits the extent to which they can substitute for energy in economic production (Stern, 1997). The energy embodied in capital goods is commonly overlooked by studies that estimate energy-saving potentials at the level of individual sectors and then aggregate the results to economy as a whole. Furthermore, many energy-economic models assume a greater potential for substitution that is allowed for by physical laws (Daly, 1997). Hence, from an ecological perspective, the potential for decoupling energy consumption from economic growth appears more limited (Table 1).

The paper provides considerable discussion and gives empirical support for the ecological perspective. This section concludes:

In sum, orthodox analysis implies that rebound effects are small, improvements in energy productivity make a relatively small contribution to economic growth and decoupling is both feasible and cheap. In contrast, the ecological perspective suggests that rebound effects are large, improvements in energy productivity make an important contribution to economic growth and decoupling is both difficult and expensive. While the empirical evidence remains equivocal, the ecological perspective highlights some important blind spots within orthodox theory that are reflected in the design of economic models used to underpin climate policy. If this perspective is correct, both the potential for and continued reliance upon decoupling needs to be questioned.

3. The pursuit of improved efficiency needs to be complemented by an ethic of sufficiency

The key idea here is sufficiency, defined by Princen (2005) as a social organising principle that builds upon established notions such as restraint and moderation to provide rules for guiding collective behaviour. The primary objective is to respect ecological constraints, although most authors also emphasise the social and psychological benefits to be obtained from consuming less.

While Princen (2005) cites examples of sufficiency being put into practice by communities and organisations, most authors focus on the implications for individuals. They argue that ‘downshifting’ can both lower environmental impacts and improve quality of life, notably by reducing stress and allowing more leisure time. This argument is supported by an increasing number of studies which show that reported levels of happiness are not increasing in line with income in developed countries (Blanchflower and Oswald, 2004; Easterlin, 2001). As Binswanger (2006) observes:

“…the economies of developed countries turn into big treadmills where people try to walk faster and faster in order to reach a higher level of happiness but in fact never get beyond their current position. On average, happiness always stays the same, no matter how fast people are walking on the treadmills”.

It is possible that an ethic of sufficiency could provide a means of escaping from such treadmills while at the same time contributing to environmental sustainability.

The section concludes:

A successful ‘sufficiency strategy’ will reduce the demand for energy and other resources, thereby lowering prices and encouraging increased demand by others which will partly offset the energy and resource savings. While this ‘sufficiency rebound’ could improve equity in the consumption of resources, it will nevertheless reduce the environmental benefits of the sufficiency measures. But since the global ‘ecological footprint’ already exceeds sustainable levels in many areas the global consumption of resources needs to shrink in absolute terms (Rockström, et al., 2009). To achieve this and to effectively address problems such as climate change, will require collective agreement on ambitious, binding and progressively more stringent targets at both the national and international level.

4. Sustainability is incompatible with continued economic growth in rich countries

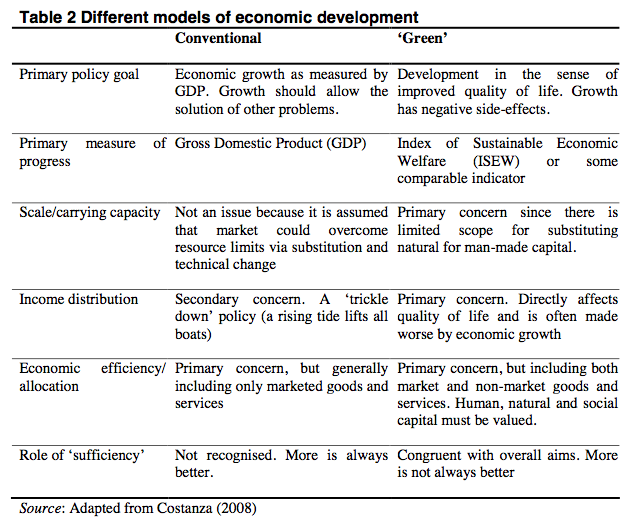

The preceding arguments highlight a conflict between reducing energy consumption in absolute terms whiles the same continuing to grow the economy. Recognising the importance of rebound effects and the role of energy in driving economic growth therefore re-opens the debate about limits to growth. This debate is long-standing and multifaceted, but a key point is that the goal of economic development should not be to maximise GDP but to improve human well-being and quality of life . . .

Table 2 compares this emerging ‘green’ perspective on economic development with the orthodox model. . .

Over the long term, continued economic growth can only be reconciled with environmental sustainability if implausibly large improvements in energy efficiency can be achieved. This point is easy to demonstrate with the I=P*A*T equation, which represents total environmental impact (I) as the product of population (P), affluence or income level (A) and technological performance or efficiency (T) (Ehrlich and Holdren, 1971). In the case of climate change, I could represent total carbon emissions, A GDP per capita and T carbon emissions per unit of GDP (itself a product of energy consumption per unit of GDP and carbon emissions per unit of energy consumption). The decoupling strategy seeks reductions in T that will more than offset the increases in P and A, thereby lowering I. . .

The required changes look even more challenging when rebound effects are considered. The I=P*A*T equation implies that the right-hand side variables are independent of one another - or at least if any dependence is sufficiently small that it can be neglected. But in practice the variables are endogenous. So while a reduction in the economy-wide emission intensity (T) may have a direct effect in lowering emissions (I), it will also encourage economic growth (A), which in turn will increase emissions. Over the long term and up to a certain level of income, rising affluence (A) encourages higher population levels (P), which will further increase emissions (I). Hence, a change in T will trigger a complex set of adjustments and the final change in emissions is likely to be lower than the IPAT identity suggests. This in turn, implies that greater changes in T will be required to achieve a particular reduction in I.

Hence, in an increasingly ‘full’ world, the goal of continued economic growth in the rich countries deserves to be questioned.

I have omitted several paragraphs of this discussion, taking about how reductions in emission would have to be vastly larger than assumed in the Stern report, to get both economic growth and 350 ppm of CO2. A direct calculation of the needed reduction in emissions would be 6.9% per year, but with the impact of Jevons' paradox, the necessary reduction in CO2 emissions would need to be much larger that 6.9% per year. This is far outside the range of anything anyone has considered.

5. A zero-growth economy is incompatible with a debt-based monetary system

An excerpt:

A purely private enterprise system can only function if companies can obtain sufficient profits which in turn requires that the selling price of goods exceeds the costs of production. This means that the selling price must exceed the spending power that has been ‘cast into circulation’ by the production process. Hence, to ensure sufficient ‘aggregate demand’ to clear the market, additional spending power is required from some other source. In a purely private enterprise system, this normally derives from investment in new productive capacity which will increase the amount or quality of goods supplied, but only after some interval. Investment therefore serves the dual role of increasing productive capacity and creating additional demand to clear the market of whatever has already been produced (Hixson, 1991). Importantly, the investment cannot be financed from savings since the resulting increase in aggregate demand would be offset by a corresponding decrease in consumption spending.

Aggregate demand is commonly expressed as the product of the amount of money in circulation and the speed with which that money circulates through the economy. Hence increases in aggregate demand require increases in the money supply or the speed of circulation or both. Increases in the money supply, in turn, lead to increases in aggregate output, the average price of goods and services or both.

The key issue is how the increase in the money supply is brought about. Governments could (and should) create the new money interest-free and spend it in to circulation in much the same way as coins and notes are created. But instead, the bulk of the money supply is created by commercial banks who print credit entries into the bank accounts of their customers in the form of interest-bearing loans. This system of ‘fractional reserve banking’ has its origins in the essentially fraudulent practices of the early goldsmiths who made ‘loans’ of a far greater quantity of gold that they actually held in their vaults. This gave them substantial profits and allowed them to increase their claims on wealth (in the form of collateral), but also served the essential function of increasing purchasing power in a growing economy. This practice gradually evolved into modern banking, with central banks imposing minimum reserve requirements and acting as a lender-of-last-resort.

A crucial consequence of this system is that most of the money in circulation only exists because either businesses or individuals have gone into debt and are paying interest on their loans. While individual loans may be repaid, the debt in aggregate can never be repaid because this would remove virtually all the money from circulation. The health of the economy is therefore entirely dependent upon the continued willingness of businesses and consumers to take out loans for either investment or consumption. Any reduction in borrowing therefore threatens to tip economies into recession.

Individual loans need to be repaid with interest, but the money required to pay this interest was not created with the original loan. While banks will recycle a large part of the interest payments in the form of wages, dividends, and investments, a portion will be retained as bank capital to underpin further loans (Binswanger, 2009). Hence, the only way that individual borrowers can pay the interest on their loans, without at the same time reducing the money supply, is if they, or other borrowers, borrow at least as much as is being removed (Douthwaite, 2000). As a result, the amount of money in circulation needs to rise each year which means that the value of goods and services bought and sold must also rise, either through inflation or higher consumption (Douthwaite, 2000). In other words, both debt and GDP must grow - with the former growing faster than the latter.

Slow or negative growth will leave firms with lower profits and unused capacity, discouraging them from investing. Less investment will means fewer loans being taken out and thus less money entering into circulation to replace that being removed through interest payments. And less money in circulation will mean that there is less available for consumers to spend, which will exacerbate the economic slowdown and cause more bankruptcies and unemployment. By such processes, the monetary system creates a structural requirement for continued growth and increased consumption.

Summary

This paper has advanced five linked and controversial propositions regarding energy consumption, economic growth and sustainability. These run counter to conventional wisdom and highlight either blind spots or taboo subjects within orthodox theory. Each raises numerous theoretical and empirical questions that deserve both detailed and critical investigation. This will take time, but that commodity is becoming increasingly scarce.

A sustainable economy needs to have much higher levels of energy and resource efficiency than exist today and policies to encourage this have a crucial role to play. But for the reasons outlined above, this is unlikely to be sufficient to meet growing environmental constraints. Instead of encouraging further growth and greater consumption, the benefits of improved efficiency need to be increasingly channelled into low carbon energy supply and improved quality of life. Quite how this can be achieved remains far from clear since a credible ‘ecological macroeconomics’ has yet to be developed. Most importantly, a crucial element of that macroeconomics - namely monetary reform - remains almost entirely overlooked. It is hoped that this paper will at least stimulate some thinking in that direction.

While the report doesn't come to this conclusion, when I read the report, the first thing that comes to mind is that if climate change plans are actually successful, they will quickly crash the financial system, based on point 5. We can debate the fallout of a crash of the financial system. It would seem to me that there could be great loss of life, at least in some parts of the world, as people are no longer able to buy food, water, and essential services.

The Stern report, which most people rely on, suggested that the cost would be modest, and growth could continue, but it is based on standard economic thinking, and thus has a very optimistic view of how energy use can be decoupled from the economy.

Gail: Obviously, any plans to address climate change without incorporating peak energy are ridiculous. And vice versa. That's not news. Both the Hirsch and Stern reports are flawed in this regard, as Rob Hopkins kas pointed out.

But the growth-based financial system is doomed for many reasons. You seem to be saying that by not addressing the climate issue (or not regulating oil sands, gas fracking, etc.) we could continue BAU. I know you don't believe that, Gail, but many of your comments seem to suggest this.

It's quite clear what we need to do -- address BOTH climate & energy. And that means deconstructing the present economy step-wise before it implodes catastrophically. It's also quite clear that the national politicians (and even President Goldman-Sachs) are willing to have it go down catastrophically.

This means we need to prepare at the individual/family/community level.

I am not saying that by not addressing climate issues, we continue BAU.

It looks to me that we are likely to crash in the not too distant future, regardless of what we do. The crash is very likely to fix the climate issue, as well as dramatically reduce the population. (It will probably also fix our ocean problems, too.)

We can attempt to fix the climate issue, but that likely just moves up the date of the population crash. The effect on climate is pretty much the same, whether we make any attempt to fix climate or not, because of the two crashes are not very far apart in timing. "Pulling the rug out" in an attempt to fix climate change could act to make the downslope worse.

From the point of the view of the planet, it is hard to see that there would be any material difference in the two crashes. But from the point of view of the people who die sooner, it could make a difference.

Every year we are adding about 70 million people to the planet. If we assume the population crash will be back to some fixed number that is sustainable, every year we put off the population crash 70 more million people will die when it happens.

So would you put "die sooner" for those now living above "die more"? If we put off the crash 5 years, many will get to live 5 years longer but 350 million more will die. When we evaluate "die sooner" that includes us so it seems important, while the 350 million doesn't include us but may include relatives if we can't get our relatives to stop having babies. Regardless any person once born has to die eventually. However the unborn might well be saved that unpleasantness if the crash comes sooner rather than later.

And of course not doing anything about climate NOW means that the sustainable number in the future may well be smaller so the total deaths could be much higher with the attempt to avoid "die sooner".

Population is a third world issue. If there is not enough available food that they can import they'll starve and that'll be it.

Floridian, if we ignore climate change in order to have BAU or some approximation of BAU for a bit longer, food may well be our problem too. I think you must have very little idea of how little of a climate change it would take to disrupt BAU in the agricultural section. IMO we are overpopulated in the US as well post peak oil even if we reduce our eating to third world standards.

But my point was that Gail was saying we should not address climate change as if we do a crash comes sooner and people die sooner, and I was saying that if we let the crash come sooner less people are ever born who have to die sooner than they might have otherwise expected. Both of us we caring about people general and neither of us discriminated between categories of people (ie first world people over third world people). Sorry you have such a narrow view of the world. Things may not play out as you expect.

It is kind of like this. We should have compassion for the poor and starving in places like Haiti and Zambia, and parts of the U.S. for that matter. However, while the left hand is providing food, the right hand needs to be providing birth control pills and other actions such as female education. Just continuing to do the same things over and over again, just reacting to each crisis, just makes the problem next time even worse.

Further, the impact of a baby born in the U.S. is way bigger than a baby born in places like India. Therefore, we should not just be pointing a finger at the third world as if they are the biggest part of the problem. Think of the carbon footprint of your children and their children for several generations. Then cut your footprint to zero and you haven't accomplished very much considering the legacy footprint of all those future children.

Well, when you decide on a final date to let it happen please let me know. I know a lot of other people who would also like to know also so please don't forget us when you decide to let the crash happen.

Ron P.

Darwinian I was commenting on Gail's comment that if we choose to deal with climate then the crash might come sooner and dieoff would start sooner. That choice is not in my hands or Gail's hands either for that matter. But the attitudes of the public have some impact on what governments might do. Thus I think it is useful for those who would rather keep putting CO2 in the air than to powerdown now at least not think that they are doing it for the sake of humanity. Humanity would be best off with a planned powerdown, but per the Hirsch report it is too late for that. Since we have waited too long for a planned powerdown, I think the best result for humanity is a quick crash sooner rather than later. I can't make that happen. I can encourage people to not have false ideas that putting off the inevitable is better for humanity even if it gives certain humans a bit more time. Pretty futile I know. BAU is so seductive. But since you want me to decide on the final date I will assert it will be tomorrow. That make you happy Ron? Come on, you know I was just addressing one point that Gail made with a different way of looking at it. Gail as a TOD personnel has more power to affect the future by promising that a few more years of BAU is OK because it puts off dieoff than I do with my little comments that while those of us living might be worse off with a dieoff soon, many unborn would remain in that blissful state.

Why?

Did the financial crash of 2008 (or 1987, or 1929) result in "great loss of life"? Historically, if there is any causal connection between financial crash and population decrease (the latter happening almost always through war), then there is at least a delay between one and the other. This delay could be a decade at minimum (1929-1939) or perhaps as long as hundreds of years (the decline of the Roman Empire). Meanwhile, some financial crashes are followed by recoveries (long or short in coming) before things get violent. Meanwhile, populations sometimes increase rather than decrease in reaction to stressful times (look at Iran, or Gaza, for contemporary examples).

From a historical standpoint I think there is very little to go on in predicting a relationship between financial collapse and population reduction.

I don't think they are talking jsut about a fincial crash. The 2008 GFC has been effectively reset by fiddling the books. You can't print oil however and when the world wakes up to that particular realisation, there is going to be one god-awful scramble to hoard the remaining supplies. I'm betting that the Chines have a long range strategic plan for that just as the USA and partners have had a more overt strategy for that past decade or more. The black hole of military adventures is just going to suck exponentially more of the economy into it until the system that brings everyone their daily bread crashes and can't get restarted before many people simply starve in place, First Second and Third World alike. I imagine though that the last one will more resilience that the first two and may indeed contain the seeds of the next civilization, whatever that may be.

Did the financial crash of 2008 (or 1987, or 1929) result in "great loss of life"?

In the US - I had posted a link to a Russian site that claimed millions died in the 1930's crash.

A more interesting thought experiment is:

What will be the reaction of Nation States to the various fraud going on in markets?

You have claims of rigged morgage markets - and the products sold off to other nations. Claims of national parks no longer held by nations but instead held by 3rd parties to secure the debt. Claims of gold bars being produced by Nation States with non-gold cores.

What happens historically when trade between Nation-States stops? What did the US of A claim back in the 1970's when it appeared that trade in oil from the Middle East was under threat?

What happens if large Nation-States say "no" to paying off debt?

WAR

“It looks to me that we are likely to crash in the not too distant future, regardless of what we do. The crash is very likely to fix the climate issue, as well as dramatically reduce the population. (It will probably also fix our ocean problems, too.)”

The thought of a crash at a magnitude that would fix the climate, reduce the population, and fix the oceans could have just the opposite effect. It would probably lead to a global conflict that could ruin the oceans, throw the climate issue out the window, but it would certainly lead to a reduction in population. In the end it could lead the world into a period of chaos that could end with a worldwide Easter Island calamity. Scary stuff Gail.

hotrod

If global heating and energy scarcities continue their current trajectory, there will be great loss of life, of both human and non human species. The damage to the planet will be much greater than an economic crash scenario.

Having said that, we appear to be conducting an experiment either way we go. While I tend to gravitate towards the idea that energy use and economic growth cannot be decoupled, there is still an element of uncertainty. Maybe this uncertainty is just my inability to fully understand the issue, but nevertheless it exists.

When I super insulate, my capital requirements increase in the short run while my expenses decrease after that. Even assuming that there is a decent energy and financial return, what is the impact of the additional funds I will have available in the future on energy use? Is it possible to maintain my current level of expenditure and reduce my energy consumption. It just seems like increased efficiency will result in more funds to be used elsewhere which will ultimately result in no significant decrease in overall energy use.

But as the author say, further investigation is required.

Not necessarily. Assume you increase your home's energy efficiency 25%. Now assume that over the next 5 years heating fuel costs as a percentage of income increase 25% (not a prediction, just an example.) The possibility is that you pay the same proportion of your income to stay in the same place. It's a gamble. You would not be as far in the hole in the scenario presented (without insulating, you would face much worse choices.) The question is whether it is an optimal solution.

A hypothetical: suppose instead of "superinsulating" (we posit now that you are living in a Centrally-heated North American conventional home)you rebuilt the south-facing portion of your house (assuming sufficient solar gain potential)into a passive-solar structure, with the potential to separate it from the conventionally-heated portion of the house in the event of an energy discontinuity? Not only do you reduce your heating costs with absolute certainty and permanence (at the very least on that portion of the house), you build in a survival cell for the unexpected. (I am pondering this scenario myself. Nobody tell my wife, please...at least, not yet.) Of course, the better solution is building or rebuilding using passive solar, but like you, I live in the real world and have to be concerned about current mortgages, lifecycle costs and resale values...just throwing these concepts out there.

No one is forcing you to buy a new Camaro, vacation 3000 miles from home or own a second home. Saying "no" is always an option.

I would not be consuming anything like the examples you cite, but my question is,does it make a difference?

Sure. You're only one family, so the difference isn't big, but sure it does.

If everyone insulated, FF consumption would fall distinctly. Unless everyone took their savings and put it directly into filling oil tanks in their back yard, it would improve the situation.

Think of it this way: if everyone in the US everyone replaced their 22MPG vehicle with a Prius at 50 MPG, it would reduce gasoline consumption by about 55%, oil consumption by about 25%, and oil imports by about 50%. That's real.

Just curious, how many people who currently drive 22MPG vehicles do you supposed could actually afford to buy Priuses right now? And what kinds of global impacts would you anticipate that would have on the availability of say lithium and the price of importing it, not to mention the entire supply chain of components that go into building that many Priuses?

My friends all drive Priuses

I must make amends

Oh, Lord won't you buy me,

A hybrid, new Benz!

Apologies to Janice Joplin.

how many people who currently drive 22MPG vehicles do you supposed could actually afford to buy Priuses right now?

The average new car sold in the US is more expensive than a Prius.

Let me say it again: the Prius is cheaper than the average car.

what kinds of global impacts would you anticipate that would have on the availability of say lithium and the price of importing it,

There's plenty of lithium: see http://energyfaq.blogspot.com/2009/02/could-we-run-out-of-lithium-for-ev...

not to mention the entire supply chain of components that go into building that many Priuses?

It's not that different from the supply chain for ICE vehicles. Sure, you'd need more electric motors and fewer ICEs. Overall, not a big deal in terms of raw materials.

Now, you may be asking about the question of a fast rampup. Well, that would be a little more difficult (we might have to do some carpooling in the meantime, if we were really were serious). But, that's not the subject of the Original Post.

How will we convince people to switch to Priuses (or carpool)? Well, it's going to be one heck of a lot easier than convincing them to accept an overall stagnating or declining standard of living....

Given that only 10 million cars were sold last year, with some subsidized by the govt., and 20 times that many cars on the road, chances are that very few can actually afford a Prius today. More can afford a 10-yo Prius, when they arrive on the lot.

Given that only 10 million cars were sold last year, with some subsidized by the govt.

That was at the bottom of the recession. Sales are about 12M now, without subsidies.

20 times that many cars on the road

50% of miles driven come from cars less than 6 years old. Turnover is faster than you might think, because newer cars are driven much more than older ones.

You might want to check Toyota's site, because I think what I saw there is more representative of real life than what you claim about the cost of a Prius. The Prius is the 3rd most expensive car in Toyota's car lineup. It's starting price is nearly identical to the Camaro.

Hybrid vehicles don't make much sense, at least as currently conceived. Think about it logically: a guy in an SUV may get low mpg and really gets hurt in the wallet when gas prices rise, so he drives and spends less! i.e. consolidates trips, doesn't go out unnecessarily, which reduces his gas consumption. Whereas the guy in the Prius happily goes on driving and even decides to take a long road trip in the face of high gas prices. So the end result is that he never really has to make the tough choice not to drive. So he ends up using even more gas. So the guy in the SUV is less resilient, but that's precisely what we need to stop growing our economy and using so much gas.

The only way out of this is to have forms of transport like trains/electric cars that don't use gas. Then people can use or not use them to their hearts content without having these overall effects on the economy.

It really doesn't work that way: neither driver changes their behavior a lot when gas prices go up: the SUV driver just complains a lot.

The only way out of this is to have forms of transport like trains/electric cars that don't use gas.

I agree.

Long road trips in hybrids don't make any more sens than an ICE. The savings are negligble on the open road. Hybrids are urban cars as will electric cars be. Agree with trains/ light rail in combination with electric urban vehicles but not necessarily the large 5 people cars we are used to.

A Prius gets substantially better highway mileage than comparable conventional cars. The Chevy Volt will do even better: when you decouple the ICE from the wheels, the ICE can operate only part of the time, which is much more efficient.

With the average person's driving pattern, a Volt would only use a gallon of fuel every 230 miles - that's about 10% of the current average. In time the battery will get larger, and that % will fall. Is it worth redesigning our whole transportation system to get that last 5%? It's less than the ethanol we're producing right now...

You might want to check Toyota's site

I tend to go by Edmunds.

The Prius is the 3rd most expensive car in Toyota's car lineup

That's not including Lexus, or Toyota's trucks. Trucks still account for about 50% of new light vehicles, and they're substantially more expensive than cars.

The average new vehicle buyer can pay less, and get better mileage, by switching to a Prius.

And have many Hybrid will live longer than a ordinary car? If they only last 10 years, it is worse if you count the embedded energy.

We don't know now, Hybrid cars are not that old.

From "Sustainable Energy - without the hot air" David JC MacKay http://www.inference.phy.cam.ac.uk/withouthotair/c20/page_131.shtml

The Prius has been around for more than 10 years now, and the batteries show every sign of lasting much longer than that.

Here's the whole quote: "If electric cars require new batteries every few years, my numbers may be

underestimates. The batteries in a Prius are expected to last just 10 years, and a new set would cost £3500. Will anyone want to own a 10-year old Prius and pay that cost? It could be predicted that most Priuses will be junked at age 10 years. This is certainly a concern for all electric vehicles that have batteries. I guess I’m optimistic that, as we switch to electric vehicles, battery technology is going to improve."

So, that's much less negative than it appears at first blush.

As it happens, his optimism has already been proved correct: batteries are lasting longer, and costing much less already.

If you didn't do any of the things cited (or like them), then your personal carbon footprint will go down. Your energy use will go down.

Will it stop all the suffering in the world?

Will it reduce it a little?

Who can say?

There is no absolution at the Oil Drum (at least, not from me, though I think somebody (Rockman, maybe?) once wrote that we should sell indulgences.)

Do the best you can.

The problem with all this analysis is that you are looking at an exogenous improvement in energy efficiency (energy efficiency drops from heaven).

By exogenous I mean an improvement not motivated by a higher real price of energy. Imagine someone invents a more energy efficient technology.

According to economic analysis, a more energy efficient technology generates a positive wealth effect. That wealth effect leads to greater demand for goods and services and hence energy as an input.

But when oil prices rise sufficiently, it will trigger energy efficiency improvments that will not generate a big net wealth effect since the oil price rise will have reduced wealth.

In other words, the Jevons Paradox will run out of the steam ...

Ironically, the Jevons Paradox is a classic example of economics at work. Technological improvements improve energy efficiency and hence lower the price of energy intensive goods.

Standard economics at its best ....

Economics as rhetoric at its best. A few of us actually try to make sense of what is going on by, god forbid, doing data mining and applying variations of statistical mechanics to the problem.

Perhaps one day the people who claim understanding will give the label the US economy is now running under.

As "vulcanologists" have been lauded and encouraged by the media in trying to predict further volcanic ability, at least we can give some encouragement to study something man-made and potentially predictable.

I like the word "enthropic" or the phrase "entropic warfare".

Sorrell's argument can be falsified if it is assumed, that Generation IV nuclear technology can effectively replace the use of fossil fuels in energy production. Most Generation IV nuclear advocates point to a multipart program of replacing fossil fuel power generation technology, with advanced nuclear generation technology, substitution of electricity for fossil fuel use in transportation, the use of electrical powered technology - for example air source heat pumps, in space heating, the use of nuclear produced heat in heat driven industrial processes, or alternatively the greater use of nuclear generated electricity in industrial setting, it does not cut it to claim that the French substitution of conventional nuclear power for fossil fuel produced electricity only lead to a 1% a year in CO2 emissions. The French did not seek to extend the nuclear powered substitution of fossil fuels beyond the primary electrical market. They did not extend electrification to other economic areas, which would be required to achieve decarbonizatton goals. By ignoring the potential of Generation IV nuclear technology and expanded electrification, Sorrell has in effect set up a straw man argument. It is of course impossible to sustain economic growth without Generation IV nuclear power, and thus adjustments would require acceptance of sufficiency.

On the other hand, with the very great low cost high output energy potential of Generation IV nuclear technology, a great deal more global economic is both possible, and probably inevitable. Since developing nations like India and China, have already opted for the high growth, high energy nuclear model, Sorrell's failure to consider nuclear power is a stunning omission, that smacks of Euro-centricism. Indian nuclear planners have stated that India has set very ambitious goals for the use of Generation IV nuclear technology as part of its future energy plans. Sorrell has pulled an ideological motivated fast one by ignoring the nuclear plans of major Asian economies.

ALL work takes energy! It always has amazed me how economists (orthodox) just can't seem to grasp this.

I wrote this back in March 2008.

That's fine, as far as it goes, but follows a tendency on TOD whereby analysis is based on a variant of the "vulgar" form of the labor theory of value, where labor is replaced with energy. The core reasoning is similar: without labor (energy), there would be no output, ergo labour (energy) is the source of all value. The problem is that this does a poor job of explaining actual prices - prices are not exactly related to the embodied labor (energy). You might want to look into the neo-Ricardian (Sraffarian) system of value, a non-mainstream approach which is based on input-output matrices and adding up constraints (the price sums up to profits plus the cost of all inputs). The approach successfully solved some of the problems with the earlier Classical theory of value and has been used to construct a logical critique of the Neoclassical theory of distribution. The same critique also applies to claims based on the Ayres-Warrs frame work that energy is undervalued by a factor of 10. In addition, this system illustrates fundamental problems with how economists think about substitution of inputs in production, and suggests that the concept relies on constructing aggregate variables (capital, labour, energy) that are inconsistent with the theory itself.

I throw the following out there as bait for you to expand further on this (pointers):

Sraffa's Production of Fallacies by Means of Fallacies

I'm trying to envision a heated discussion between two economists, but I can't quite form the image in my head.

I am not sure whether the Neo-Ricardian theory is correct, but I concur that there is definitely a vulgar view of energy on this site. Too many people act as though energy is the source of all value. Labor, skills, technology, capital are viewed solely in terms of the energy they require.

You can make the counterargument that technology is the source of value since raw energy is itself is completely useless. It is only through man's inventions such as the combustion engine that we were able to harness energy.

Not to mention the potato. Great invention, that.

Not to mention the potato. Great invention, that.

Not if you were Irish in the 1840s

Economists recipe for making Potato Vodka... note they ignore energy inputs and don't even mention yeast. But please drink it responsibly...

http://www.squidoo.com/How-To-Make-Potato-Vodka

"It is only through man's inventions such as the combustion engine that we were able to harness energy."

Or, we could say that it is only through the use of raw energy that man or woman is able to stave off the unwanted advances of entropy and atrophy and remain alive, let alone invent combustion engines.

It could be that I'm missing something because I'm thinking too much from a physics/thermodynamics perspective, admittedly I have relatively little training in any type of economics, but I really can't see how you could have a vulgar enough view of energy. We literally could make NOTHING happen without it. If I come up with a way to increase the efficiency of a process at the plant at which I'm an engineer, are my skills and labor responsible? Or, was it only possible because of the roobis tea and cereal I had for breakfast that kept me nourished enough to remain alive and think clearly. In today's industrial economy, that food traveled thousands of miles using energy intensive methods. I would agrue that the natural gas that was used to make ammonia that fertilized the wheat that went into my cereal that nourished me the morning my labor and skills came up with the innovation is more the ultimate source of the new innovation than my labor and skills, since I wouldn't have been able to use my labor and skills without the natural gas that made the fertilizer that made the food.

Lorax:

That is what net energy is all about. Or if you want to get deeply into the micro of it, H.T. Odum's eMergy analysis Yes, eMergy (not a misprint). It is an energy flow chart, much like the early flow charts you studied as a kid in Richard Scary's books, such as "What Do People So All Day?"

You are not missing anything. It's economists who refruse to understand the practical results of the 2nd Law of thermodynamics on the net yield of alternate fuels and the practical results of this.

Cap'n Daddy

And while you are looking at eMergy Lorax you can go to Sourceforge and download the java program that models eMergy.

(somewhere in my profile is the link to the 1937 energy as money paper by the Technocrats)

It's because they know so much more than everyone else...though that might just be a refurbished ruse ;-)

Yes, energy is important. OTOH, the same can be said for air; metals; water; and a lot of other things to a lesser degree.

I call this the garbage-man's fallacy: during the NYC sanitation-worker's strike, the claim was heard that no worker should be paid more than the sanitation-workers, because without them the city would grind to a halt.

Just because something is essential, doesn't make it the only thing that's important, or even the most important on a day-to-day, functional level.

But Christ, it is hard for this little bunny to ignore the big Mac truck roaring down with headlights glaring.

An alternate answer to this question, at least, derives from looking purely at the changes in the global economy that have happened over the last 25-30 years, without reference to BTUs at all. Thirty years ago, when the Fed incented banks to create cheap credit, the Fed had a good idea where it would go. Lending standards for mortgages, both residential and commercial, meant it didn't go into construction; the large expenses associated with securities trading (raise your hand if you remember large odd-lot fees) meant it didn't go there; restrictions on international capital flows meant it had to pretty much stay in the US. So it went to businesses who could make a reasonable case for expanding to a conservative banker, and the borrowers had to hire domestic labor to do useful things.

All of those restrictions have disappeared, and if Dr. Bernanke were honest, he would admit that he doesn't know where the cheap credit will go after he creates it. Although the evidence from the recoveries of the last recessions in the early 1990s, the early 2000s, and now is that he should know that the place it probably won't go is into wages and salaries for workers in general.

Sorry George, but economists are quite aware that work takes energy.

The issue is whether energy is a binding constraint or not. If there is 10 trillions barrels of economically viable oil, then the constraint is not binding for the next half century or maybe the next one hundred year. In the long run we are all dead as Keynes noted.

If the Peak Oil crowd is correct (and I believe they are), then the constraint is binding in the near term, which is pratically speaking, an entirely different matter.

You can't do intelligent energy modelling without taking price into account. And there is no alternative to economics for analyzing the impact of prices on scarce goods and services.

The Jevonx paradox is best understood using standard economic analysis.

Perhaps you should tell the trophic (systems) ecologists. They are unaware that monetary price has to be taken into consideration in their models.

Sorry for the sarcasm. But the fact is that exergy is the only meaningful currency whether you are talking about trophic networks in nature or human economies. Price would be a perfectly good means of communicating value if money had a more direct relation to exergy, e.g. an energy standard based on total available energy to do work in the future, or net energy available to the economy (sans the energy sector that is modeled with EROI). Some writers prefer emergy accounting (for cost build up as indicated in my linked post above). It is an alternative but records after-the-fact uses of energy as opposed to future potential work. One suggestion is to use emergy for cost accounting as H.T. Odum and many others have suggested, and exergy calculations for monetary policy, e.g. setting the amount of money in circulation. Except for ecological and biophysical economists, the prevailing voices in economics don't even have a clue about what I just described.

It is this lack of understanding that the orthodox economists have failed to grasp and hence has led to their many mistaken predictions (I love this Krugman gem, one of the few things I think he gets straight).

exergy is the only meaningful currency whether you are talking about trophic networks in nature or human economies.

Natural systems are very, very different from human systems with extrasomatic energy. In almost all natural systems energy is very scarce. Currently humans systems have quite a surplus of extrasomatic energy, and that's highly likely to continue.

But the principles of energy flow and work are the same. Work produces wealth in the economic sense. And our so-called exosomatic energy is about to get scarce too.

And our so-called exosomatic energy is about to get scarce too.

That's where we disagree. We have an enormous amount of coal, and wind and solar (and nuclear) are relatively very easy to harvest. We will use coal before we allow economic collapse (or even a relatively modest descent).

It would be relatively easy to ramp up wind power to replace coal. Will we do it? I'm not entirely optimistic on that, but we do have the choice available to us. We will certainly make that choice rather than reduce overall energy/exergy dramatically. And...that's ok, as wind has a very light "footprint".

Nick,

You claim this is the case. But I would seriously like to know how you came to believe it. What data are you looking at that gives solid evidence that this is so? I certainly read the popular MSM stories (including the nonsense now being published in Scientific American) about this engineer or that scientist working on breakthrough technologies that will help solve the energy problem. But just when are these breakthroughs going to hit the market? I also note that most of these stories are wishful thinking by the reporters more than clear evidence that we have somehow beaten the laws of thermodynamics.

If you really want to look at data and its interpretation please study Charlie Hall's Balloon Diagram and then note particularly where wind and solar (and nuclear) map into the scheme of things. Coal? Yes, there seems to be a lot of it left and you may be right that in desperation we will turn to it to try to keep things going. But there are many technical and social problems with doing so. One of the first things that will have to be done is to figure out how to extract coal using coal or a liquid fuel derived from coal, since diesel fuels will be in short supply and are currently the primary energy source for extraction.

You really need to dig deeper and distrust any claims you read or hear in the MSM. Go to the primary literature if you want reality.

What data are you looking at that gives solid evidence that this is so?

I believe I've read most of Cutler Cleveland and Charlie Hall's reports. It's perfectly clear that wind's E-ROI is sufficiently high, with existing technology.

please study Charlie Hall's Balloon Diagram

I have, many times. If you look closely, you'll see that wind's E-ROI is well above the minimum line. More importantly, Cutler Cleveland's summary of the literature http://www.eoearth.org/article/Energy_return_on_investment_(EROI)_for_wind_energy shows that wind's E-ROI is around 19 sometime ago, with much smaller turbines. If you study his sources, you'll see that that most of the studies are quite old. If you look at the turbines used in those studies, you'll see that the turbines studied were much smaller than those in use today - look at Figure 2, and read the discussion. If you study that chart, you'll see a very clear correlation between turbine size and E-ROI. It's perfectly clear that Vesta's claim for an E-ROI of around 50 is perfectly credible.

Furthermore, it's silly to suggest that there is an important difference between an E-ROI of 20 and an E-ROI of 50. It's like miles per gallon: we're confused by the fact that we're dividing output into input, when we should be doing the reverse, and thinking in terms of net energy. An E-ROI of 20 means a net energy of 95%, while an E-ROI of 50 means a net energy of 98%: there really isn't a significant difference.

Coal? Yes, there seems to be a lot of it left...But there are many technical and social problems with doing so. One of the first things that will have to be done is to figure out how to extract coal using coal or a liquid fuel derived from coal, since diesel fuels will be in short supply and are currently the primary energy source for extraction.

CTL is perfectly feasible, but I don't think we'll actually do much of it. It makes much more sense to go to electric transportation, as discussed here: http://energyfaq.blogspot.com/2008/09/can-everything-be-electrified.html

diesel fuels will be in short supply and are currently the primary energy source for extraction

1st, electric coal mining is widely done today: Much mining, especially underground, has been electric for some time. Caterpillar manufacturs 200-ton and above mining trucks with both drives. Cat will produce mining trucks for every application—uphill, downhill, flat or extreme conditions — with electric as well as mechanical drive. Here's an electric earth moving truck. Here's an electric mobile strip mining machine, the largest tracked vehicle in the world at 13,500 tons.

2nd, diesel will be around for quite some time. Aleklett projects an 11% decline in all liquid fuels by 2030, and that decline will come out of personal transportation, not industrial/commercial activity: industrial/commercial will outbid personal transportation.

uh, wow, please don't keep repeating this. Whatever you're talking about here, it's not to be labeled 'net energy'. A net energy of 95% would be an EROEI of 1.95. An EROEI of 20 means a net energy of 19 (or 1900%) and an EROEI of 50 means a net energy of 49 (or 4900%). There's a huge difference there, that would vastly change the speed at which wind would replace other sources.

That said, I'm inclined to agree that as far as whether it makes sense to adopt wind power, the difference between 20 and 50 is not so important. ;-)

hmmm. I wonder what a good term would be for the percentage I was using. % net energy?

I can't think of anything very elegant. "net energy as percent of energy produced" is about the best I can do.

It might also be useful to turn things around and talk about "input as percent of output", which would be 5% and 2% in the above example.

Yes, I think "input as percent of output" makes sense - it highlights the relative size of the amounts.

Yes, I think "input as percent of output" makes sense - it highlights the relative size of the amounts.

Thank you for answering my question. I think I can see more clearly where you are coming from. That probably concludes our discussion.

Ah, but does what I said make sense to you? If not, why not?

We've had this kind of conversation before, and not finished. I like pursing dialogue until some kind of agreement is reached. I think we've made substantial progress - for instance, we've come to agreement on coal resource availability, and the likelihood of it being used if needed.

What the heck, let's keep on going!

George, Charles Hall's account of the potential of nuclear power was written by a poorly informed graduate student, who admitted that he had learned quite a lot from the criticism his essay received. i am not sure that Hall learned as much. I have argued that deployment of nuclear power can be drastically scaled up by factory manufacture of small generation IV breeder reactors, and that enough thorium is recoverable with acceptable ERoEI to power provide all of the human population of Earth with all of the energy it requires for until solar evolution makes the Earth uninhabitable.

I was OK with your comment right up to this point:

That is hyperbole. It makes it hard to then take the rest seriously.

I have no idea what Charlie Hall may or may not have learned about nuclear. It is true that the Balloon diagram is dated and I believe he may be working on a newer version with more recent EROI numbers. We never discussed nuclear in the mix. I myself am for the development you refer to but not as a means of taking care of all of humanity's needs forever (how many humans did you have in mind?)

If you have a well worked out paper on the EROI and practical feasibility of these reactors, then publish and let it be counted in the development of a new diagram. If, on the other hand, you are merely stating an opinion then please don't get angry just because others who do publish in the primary literature don't take your word for it.

George, what makes you think that my statement about recoverable thorium resources is a hyperbola? Do you know what are the recoverable thorium resource and how efficiently those resources can be used in Generation IV reactors? My complaint against Charles Hall was that he discounted nuclear power before being well informed about its potential. You seem far to willing to do the same.

In fact there are an estimated 120 trillion tons of thorium in the earths crust. and it can be recovered with favorable EroEI at well below average crustal concentration levels. Phillip Morrison, Harrison Brown, and Alvin Weinberg established all of this a long time ago.

http://nucleargreen.blogspot.com/2010/02/will-we-run-out-of-uranium.html

http://www.theoildrum.com/node/6116#comment-578474

OK, let me make it clearer. This is the hyperbole:

I have no knowledge of thorium recoverability or much else about nuclear. Thanks for the links but they don't appear to be scientific papers published in journals.

george where do you find a hyperboly. 1500 tons of Thorium will more than supply the United States with all of its energy needs for a year. Assume that global energy demand per person is the same is the same as that of the United States. That would require 45000 tons of thorium. In a Billion years that will equal 45 trillion tons about a third of the thorium in the earths crust. Remember most crustal thorium is recoverable with a favorable ERoEI. But in another billion years a very large amount of thorium with be introduced into the earth's crust by volcanic processes. Thus it seems plausible that the global thorium supply will never fail.

In almost all natural systems energy is very scarce.

Natural systems are powered (mostly) by the same amount of photons hitting the planet. photon -> plants -> animal muscle -> work has a very poor conversion rate. photon -> PV -> watts -> work is a far better conversion rate.

Currently humans systems have quite a surplus of extrasomatic energy, and that's highly likely to continue.

But as we are fond of saying at TOD - Untill it doesn't.

Untill it doesn't

Unless it does. :)

We really need to have a more detailed discussion than that....

George,

I completely agree with you on this post.

I just can't believe it isn't slap in the face obvious to everyone!!

Keep at it because I am convinced you are on the right track and the future will prove that Energy/Exergy/emergy as the basis for economics

is the only true economics.

We are at the cusp of a major paradigm change.

I just wish there was some way that I could get involved as an agent for this inevitable and absolutely necessary change.

We need to clean house and fire all the current policy makers and their advisers.

They are destroying any chance that we may have left to turn the tide and re-align with nature.

We need the University of Noesis...........Yesterday.

By the way have you ever heard of the Astronaut Edgar Mitchell?

Thanks Porge.

I have indeed heard of him! I've even met him at a conference on anticipatory computing in Liege Belgium back in the late 90s, the year of the total eclipse in Europe. He gave a keynote talk. I think that is where I first heard the term noesis used to describe knowledge as both process and stuff (my paper on prototypical intelligence and how I had developed a robot brain to demonstrate it can be found here).

I had previously seen the use of noos (Greek - mind) in Teilhard de Chardin's term "noosphere". I liked Mitchell's thoughts about consciousness, but the psychic stuff was a bit much for me. We took a field trip to the European Space Center and watched him harness up to the moon walking simulator and show us how it was done! What a blast.

The University of Noesis, for those who don't know, is my dream of what education could be if we weren't all so enamored with getting a job and making money as the point of school.

Yes, I often point out the first law of thermodynamics when talking with people who think energy conservation will take care of everything. We must have useful energy to do WORK.

Pure speculation here, but I believe that the economy behaves as if it has a great deal of inertia. The basis of that inertia is debt. Debt service drives much of the economy. Those debt obligations tie us to the status quo so long as those obligations persist. Reforming the monetary system away from debt/credit to value based currency would be a big help, but how is that to be accomplished when debt obligations are already in place? How are those contracts supposed to be honored or abrogated? In the political space, is it reasonable to expect the most powerful lobby in Washington to suddenly fall on their swords?

It seems more likely to me that changes to fundamentals like the kind of monetary systems we use will come after a collapse of the existing institutions. The current players must first be removed from the game. There will likely be a great deal of luck involved in what fills the vacuum.

Could Mr. Sorrel please tell the engineers and scientists where to start on increasing energy efficiency? The last time I checked we have just about squeezed the last percent out of the cycles.

"The pursuit of improved efficiency needs to be complemented by an ethic of ‘sufficiency’."

I take it that "sufficiency" is the new code word for voluntary reduction in energy consumption. IOW folks will voluntarially reduce their life styles for the benefit of mankind as a whole. And I suppose if voluntary sufficiently isn't embraced universally then we can go to gov't enforced sufficiency. And given how the political system is working today I suppose we should expect some portions of society to be forced to be more sufficient (more rationing) then others. Sorta like we're all equal...just some are more equal then others.

I think 'voluntary' sufficiency will only occur when we re-engage with local communities. It can only happen then the dominant moral ethic is one of managing resources for the 'good of society'. This was part of the morality of many Polynesian societies, and has traditionally been associated with native american tribes. It is (or was recently) a sub-text in Indian morality, when high population density has learned to cope with resource limits and frequent famines for millennia.

It is a morality which is now derided in the world dominant culture, which treats Malthusians as deluded misanthropes, and is the opposite of the 'American Dream'.

It will require the suppression of the rights of the individual in favour of the needs of the 'family', 'tribe' , 'nation', 'mankind', 'planet' - take your pick.

It won't happen this side of collapse.

I'm a misanthropic Malthusian.

:)

Ah, yes, the tired old Myth of the Noble Savage. But I guess the chiefs who ordered the building of the Stone Heads were unconstrained by this particular noble "morality". Which might even lead a person to wonder if anyone was ever seriously constrained by it, except possibly in the eyes of a few wishfully thinking "anthropologists" seeing the world as a Walt Disney movie.

PaulS,Easter Island was only one of hundreds of Pacific island communities and the only one that I know of which indulged in an orgy of monument building.

While the notion of the Noble Savage may be a myth our present system has many mythical notions some of which you,no doubt,are a part.

Many of us already engage in voluntary sufficiency. Unfortunately, we don't have time for the hundreds of millions of others to get on board. Of course, we also have those engaging in involuntary insufficiency, which will increase in numbers after the collapse.

Does that mean some of us get real sugar while the rest of us get "Equal" (aspartame, dextrose and maltodextrin) artificial sweetener? The real question is what is the EROEI of "Equal"

I think some of us are going to want to get "Even"...

If I understand your point (ie, "cycle" as in Carnot), there are still gross inefficiencies in the overall system. Typical household lighting is terribly inefficient at watts to lumens. Typical domestic heating is inefficient not because the furnace is inefficient, but because the heat is lost so quickly to the outside because of poor insulating properties. Electric transportation from wind turbine to wheels is much more efficient than almost anything that includes some sort of internal or external combustion. Land use policies in many areas almost guarantee that large concentrations of jobs will be located where there is no mass transit.

The engineering/science for most of those improvements has already been done. The hard parts remaining are in public policy and economics. To focus on the land use example: (1) economics because the creator of the large tech campus on the outskirts does not pay for the externalities of transportation; and (2) public policy because enforcing those externalities is hard to do politically.

Comment 5 is complete nonsense. Only central banks create money. This is then loaned out to commercial banks. A commercial bank which tries to utilize the methods described will soon be bankrupt. No central bank would ever relegate the creation of money to commercial banks; unless one wants to lump in the Federal Reserve banks which are a rather lame attempt to avoid the reality of having a central bank system while actually having a de facto one.

The piece is riddled with similar 'deficiencies' which I'll leave to those with more time on their hands to delineate. I have serious work to do.

Apparently you're not familiar with fractional reserve banking. Currency and moeny aren't the same thing.

I suggest you read up a bit more on how the financial system works. If I get a mortgage to buy a house I get the money from the bank. The money I get has come from depositors. However, the credit in the depositors account does not change. In other words the bank tells the depositor that they have so much money, but they have actually given it to me. So you have a larger amount of money in circulation. The pretend money in the depositors bank balance and the money I have borrowed. If I cannot pay back my loan and the value of my property is too low, the money in the depositors bank account evaporates.

This is exactly the reason the banks would be bankrupt if the government had not stepped in, lending them money at 0.5% interest and borrowing it back for 5%, with the banks keeping the difference.

**Only central banks create money** Not sure where you get your info from, but commercial banks create money all the time. It's called fractional reserve banking, you can learn about it in any basic econ book. Basically, if I'm a local bank, and you deposit $10 at my branch, and I loan out $9, then I have created money. Because, you still have $10 in your name, and some borrower now has $9. The money supply has increased, money has been created. Hope this helps. Luke

Petrosaurus, Have a read or listen to this guy

http://www.financialsense.com/Experts/2006/Griffin.html

Petrosaurus,

WRONG

Read this.

It is called the reserve multiplier and it is the 90% (10% reserve requirement) that is lent by one bank being deposited in another bank that then again lends out 90% etc. etc.

It creates about 10 times the amount of credit in the system that the fed puts in.

It is blatant fraud.

http://www.rayservers.com/images/ModernMoneyMechanics.pdf

I see a lot of people beat me to the punch but this is the official Chicago Federal reserve publication.

It's not fraud. It's an efficient use of the underlying reserves (the funds held on deposit at the Fed).

It creates inflation which is theft by another definition.

Funds? They hit a few keys on a computer keyboard and voila new money?

"The Federal Reserve believes it is possible that, ultimately, its operating framework will allow the elimination of minimum reserve requirements"

And when the removal of minimum reserve happens - what then?

(and I note that you are not saying/backing up the original claim of 'only central banks can create' is correct.)

Actually, you're wrong. Commercial banks use a fractional reserve system. In essence, their loans increase the money supply. It is very simply. A bank when it makes a loan credits money to an account. It is creating money.

Afternoon Roderick.

Have you done the Crash Courseby Chris Martenson?

I do believe that most of us here on the Oil Drum are influenced by it.

Would you mind critiquing it for us?

I've reviewed it. It's pretty well written, but many of it's crucial points are unrealistic. In this case, I didn't see anything to show that economic growth is necessary to our system.

17c says "Distributing ever-larger shares of money during a period of constant growth is a pleasant job that enjoys broad political and popular support. Operating in a world of declining energy is an utterly new prospect for every single political and financial institution. It makes the science of meeting unlimited demand with limited resources even trickier, if not impossible, if the system is not up to the task."

This could be said about communism, fascism or capitalism. It's not very specific to "our system".

Again, it says "if the system is not up to the task."

Well, is it or isn't it? If not, why not?

Unless you are kidding.

You can read the Chicago Federal Reserves Publication on the Fractional Reserve system.

Google: Modern Money Mechanics.

It is all in there and it is official.

Look at my post a few above this one and there is a link.

"This could be said about communism, fascism or capitalism. It's not very specific to "our system".

Posted by Nick

Actually, I think Nick has a point here. It's not just OUR system that requires growth, its ALL the political and economic systems, ALL the ideologies and isms that we have been experimenting with (at least on any scale) since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution.

So how do we devise political and economic systems to function when the economic growth is gone and replaced by contraction? We can't just "go back" to the previous arrangements, at least not in any near-term time frame because those were agrarian societies, and while we are likely to return to this state, it will likely take a century or two. Big ag and the rest of the physical and political infrastructure of the modern era won't just disappear and be replaced with pre-industrial institutions, economies and structures overnight.

So the question to me is not so much where we will ultimately end up after a few centuries, but how we will get there, and how much chaos will have to be endured while the unwinding of our current arrangements transpires.

Antoinetta III

A3,

Energy/resource based economics a la Hubbert etc.

It's not clear to me that Capitalism can't limp along showing "profits" even as real productive growth and energy consumption fall. Inflation can do the work. It probably can be controlled well enough by central banks to keep from getting out of hand. It's still a competitive game. The tread mill just isn't going "up" any longer.

I just recently wrote a blog essay on The Growth Conundrum which looks at some of the statistics over at Gapminder.org. It seems on-topic with this post.

http://squashpractice.wordpress.com/2010/04/17/the-growth-conundrum/

It doesn't take too long for people to catch on the inflation is to be expected in the future, so one needs even higher interest rates. This quickly becomes too expensive. I don't think it works.

Even now there is expected inflation. Hence, contracts are made with COLAs and interest rates are set with inflation in mind. And society functions. The advantage of a slightly higher base inflation rate is that the economy can contract and we can still have positive interest rates. Right now interest rates are running into the zero bound, so all kinds of other tricks have to be used to prevent an all-out deflationary episode. Allowing interest rates to drop significantly below the expected rate of inflation lets central banks have more control over our fiat money supply during downturns. During the good times, general inflation means that we all have to keep pedaling to stay afloat.

There are a few prominent economists (Krugman) that think the target inflation rate should be higher.

Many folks say that capitalism won't work when growth stops. I'm not so sure. One's relative position in the economy is still dependent upon the same work and innovation incentives. Growth in nominal terms never ceases. Just the real value of what we have slowly disintegrates over time - much like the real world around us could during a post-peak collapse.

I am sadly coming around to Jay Hanson's view that our collective behavior is primarily governed by biologial laws and that we will grow exponentially until we can't at which point we will crash.

Have been studying history looking for any evidence that humans can voluntarily override our biological program. Have not found any yet.

If anyone can point me to some history that proves we are capable of collective decisions to limit today in favor of tomorrow I would be grateful.

Well I suppose Jared Diamond in Collapse gives some examples of societies recognising the problem of diachronic competition. But the problem is that I can't recall JD stating this worked in a democracy.

James Lovelock gave and interesting interview about the dilemma -

http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2010/mar/29/james-lovelock-climate-change

Lovelock didn't appear to say humans were too stupid, but suppose it makes better copy.

While I don't like the idea of die off, I think the probabilities are very high, exactly when or how is unclear. It would be good to adopt the precautionary principle. China adopted a one child policy, could you imagine that working in developed countries?!

Another one on ecological denial

http://www.greatchange.org/ov-catton,denial.html

Thanks.

My son said he learned in school last week that China has revoked its one child policy. I have not been able to confirm.

Yes, well, that's because it's false, officially. On the other hand, China has never strongly enforced the one child policy, and I think has weakened enforcement in more recent times. And that may amount to the same thing.

I disagree. He gives examples in Australia and Montana. (Also Tikopia is small enough to probably be considered democratic in some way.) Granted, these examples are all somewhat weak.

I am a fan of Lovelock.

It is not that we are stupid but..

It is my opinion that democracies have too many balances of power built in to be effective.

On the other hand dictatorship is hardly attractive.

I conclude that if the situation is too be optimised some power will have to be relenquished in order for an educated and benevolent el Presedente to bring in eMergy.

Western Constitutions are so yesterday, designed for conditions of growth.

(Please don't reply that one man's benevolent autocrat is another man's dictator. A bad situation will need to be optimised. Survival has it's price.)

Lovelock is a loon.

He says climate change will be an unparalleled disaster, and in the same breath condemns wind power because it will ruin the view in the English countryside!!

----------------------

Please don't reply that one man's benevolent autocrat is another man's dictator. A bad situation will need to be

That can go the way of Bush (who disregarded his promises and good public policy) just as easily.