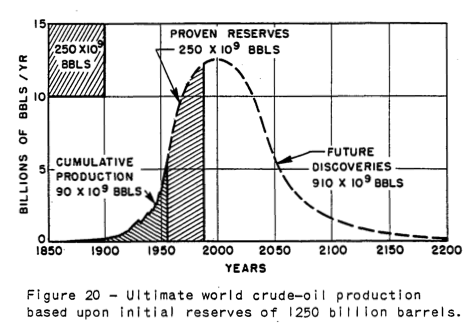

Will the decline in world oil supply be fast or slow?

Posted by Gail the Actuary on April 18, 2011 - 11:15am

An Oil Drum reader wrote, asking the following question:

Dear Oil Drum Editors,

I have been reading quite a bit about peak oil recently. I get the impression (not based on data) that at some point there will be a quite steep decline in oil production/supply, and therefore we will see dramatic changes in how the world runs. However, when I look at oil depletion rates and oil production declines based on the Hubbert Curve, it seems to suggest a rather smooth decline. How is that some people expect a serious energy crunch in about two or three years, then?

Many thanks! --Curious Reader

Below the fold is my answer to him.

Dear Curious,

It seems to me that

(1) A slow decline assumes that the only issue is geological decline in oil supply, and the economy and everything else can go on as usual. Technological advances and switches to alternatives might also be expected to help keep supply up.

(2) A fast decline can be expected if one or more adverse factors make oil supply decline faster than geological factors would suggest. These might include:

(a) Liebig's Law of the Minimum - some necessary element for production, such as political stability, or adequate food for the population, or adequate financial stability, is missing or

(b) Declining Energy Return on Energy Invested (EROEI) interferes with the functioning of society, so the society generates too little net energy, and economic problems ensue, or

(c) Oil becomes so high priced that there is little demand for it. This would quite likely be related to declining EROEI.

My view is that some version of the faster decline scenario is likely, because we will hit limits that interfere with oil production or oil demand.

Let me explain my reasoning.

Declining EROEI

EROEI means Energy Returned on Energy Invested. It can be defined as the ratio of the amount of usable energy acquired from a particular energy resource to the amount of energy expended to obtain that energy resource. Wikipedia says,

When the EROEI of a resource is equal to or lower than 1, that energy source becomes an "energy sink", and can no longer be used as a primary source of energy.

The situation is really worse than Wikipedia suggests. An economy needs a certain level of energy just to keep its infrastructure (roads, bridges, schools, medical system, etc.) repaired and working, and citizens educated. So energy resources, to really be useful, need an EROEI significantly higher than 1 to maintain the system at its current level of functioning.

How much higher than 1.0 the EROEI needs to be on average will depend on the economy. An economy such as that of China, with relatively fewer paved roads and less expensive schools and healthcare system can probably get along with a much average lower EROEI (perhaps 4.0?) than an economy like the United States (perhaps 8.0), because of lesser infrastructure demands.

If the average EROEI available to society is falling because oil is becoming more and more difficult to extract, an economy with a high standard of living such as the US would seem likely to be affected before an economy with a lower standard of living, such as China or India or Bangladesh, because of the higher EROEI needs of the more extensive infrastructure. Ultimately, though, the world is one economy, so problems in one country are likely to affect the economies of other countries as well.

There a couple of issues related to declining EROEI:

1. High cost to extract. Sources of oil or natural gas or coal that are difficult (high cost) to extract tend to be lower in EROEI than sources that are low cost to extract. So high cost of extraction tends to be a marker for low EROEI. We are increasingly running into this issue, for both oil and natural gas.

2. Declining Net Energy. EROEI is closely related to "Net Energy," which is the amount of usable energy that is left after deducting the energy that it takes to make energy. When net energy decreases, we have less energy to run society, making it difficult to do things like maintain bridges and roads, and fund schools.

So high cost of oil extraction, low net energy, and low EROEI are all very closely related.

What did M. King Hubbert Say?

M. King Hubbert in various papers such as these (1956, 1962, 1976) talked about a world in which other fuels took over, long before fossil fuels encountered problems with short supply.

In such a world, there would be plenty of net energy from alternative fuels to run society. Because of this, even if fossil fuels ran low, it would be easy to maintain the economy's infrastructure, without disruption. In Hubbert's 1962 paper, Energy Resources - A Report to the Committee on Natural Resources, Hubbert writes about the possibility of having so much cheap energy that it would be possible to essentially reverse combustion--combine lots of energy, plus carbon dioxide and water, to produce new types of fuel plus water. If we could do this, we could solve many of the world's problems--fix our high CO2 levels, produce lots of fuel for our current vehicles, and even desalinate water, without fossil fuels.

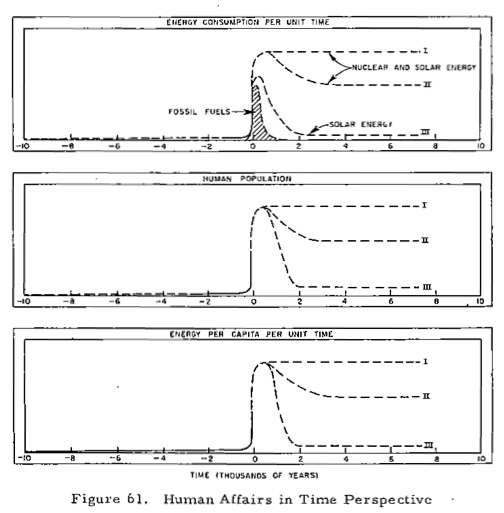

He also showed this figure in his 1956 paper:

In this figure, most of the additional energy comes from nuclear energy, while a smaller amount comes from "solar" energy. By solar energy, Hubbert would seem to mean solar, wind, tidal, wood, biofuels, and other energy we get on a day-to-day basis, indirectly from the sun. His figure seems to suggest that solar energy would basically act as a fossil fuel extender, and would not last beyond the time fossil fuels last. The primary long-term source of energy would be nuclear.

In such a world, applying Hubbert's Curve to world oil supply would make perfect sense, because there would be plenty of other energy, to provide the energy needed to keep up the infrastructure needed to main extraction of oil, gas, and other fuels as long as they were available. Even liquid fuels and pollution wouldn't be a problem, if they could be manufactured synthetically. The carrying capacity of the world for food would eventually be a factor, but in one scenario in his 1976 paper, he shows the possibility of world population eventually reaching 15 billion people, thanks to the availability of other fuels.

Another Approach to Forecasting Future Oil Supply: Limits to Growth Type Modeling

Another approach estimating the shape of the decline curve is by applying modeling techniques, such as used in the 1972 book Limits to Growth by Donella Meadows et al. The factors considered in this model were population, food per capita, industrial output, pollution, and resources. Resources were modeled in total, not oil separately from other types of resources. There were 24 scenarios run. The base scenario suggested that the world would start hitting resource limits about now (plus or minus 10 or 20 years). There have been several analyses regarding how this model is faring, and the conclusion seems to be that it is more or less on track. This is a link to such an analysis by Charles Hall and John Day.

With this type of model, according to Limits to Growth (p. 142), "The basic mode of the world system is exponential growth of population and capital, followed by collapse." This type of decline would seem to be substantially faster than the decline predicted by the Hubbert Curve.

One thing I notice about the Limits to Growth model is that it leaves out our debt-based financial system. Since so much capital is borrowed in today's world, it seems like including such a variable would tend to make the system even more "brittle", and perhaps move up the date when collapse occurs.

Also, the Limits to Growth model is for the world as a whole, rather than for different parts of the world. Different areas of the world can be expected to be affected differently, as oil gets in shorter supply. The effect of this would seem to be to push economies which have a higher need for oil (illustrated above with my estimate that the US requires a EROEI of 8.0 on energy resources) down toward economies that use smaller amounts of oil (illustrated by my rough guess that perhaps China could get by with an EROEI of 4.0), especially if they trade with each other. I explain how I see this happening in a later section of this post.

Demand for Oil (or other Fossil Fuels)

Even if there is plenty of high-priced oil extracted from the ground, if potential buyers cannot afford it, there can be a problem, leading to a decline in oil production. Demand can be thought of as the willingness and ability to purchase oil products. Many people would like to have gasoline for their cars, but if they are unemployed, or have a part-time minimum wage job, they are likely not to have enough money to buy very much.

Over the long term, declining demand can be expected because of declining EROEI, as illustrated by Prof. Charles Hall's "Cheese Slicer" model.

Declining demand, and ultimately lack of sufficient demand to support supply, is related to the much larger size of the big black "energy needed to create energy" arrow as resources become more and more difficult to extract, and the much smaller size of the red discretionary spending arrows. When the discretionary spending arrows are small, people can't afford the oil that is produced.

Lack of Demand Can Be Expected to Affect the More-Developed World before the Less-Developed World

Let me explain one way I see lack of demand for oil arising in the developed world today. This is related to the tendency of economies with high required EROEI to maintain infrastructure to be the first economies to be affected by declining EROEI, and by the tendency of free trade to lead to equalization among economies.

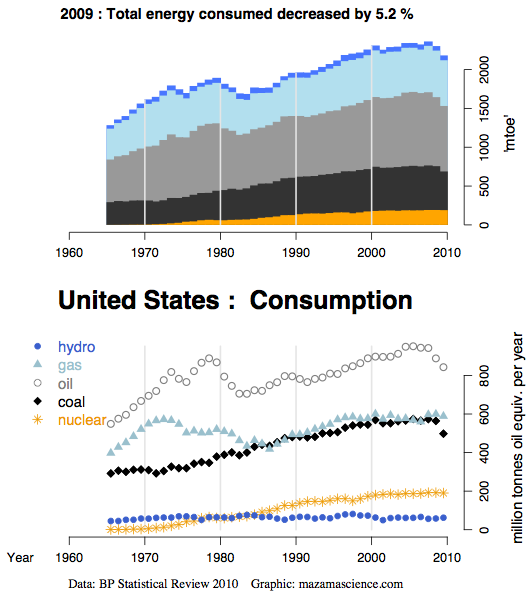

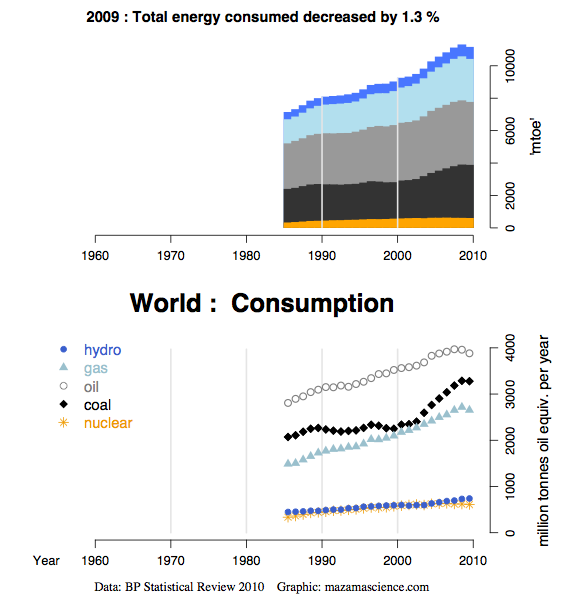

US energy consumption in general, and oil consumption in particular, has been relatively flat in the 2000-2009 period, and declining at the end of that period, indicating low demand. Prior to this period, it was rising.

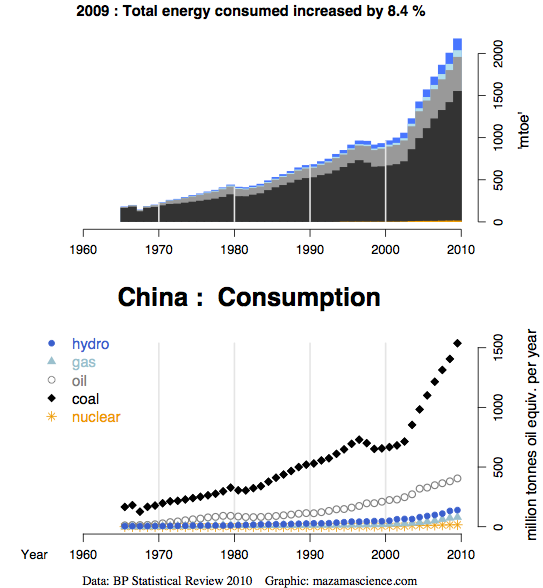

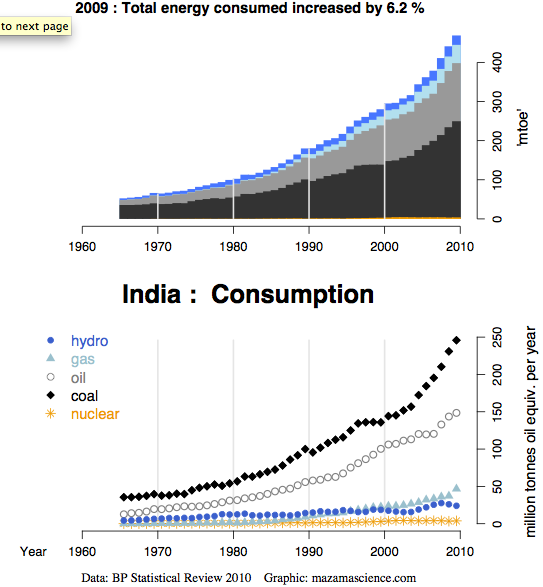

More or less the reverse has happened in China and India. Growth in oil use and energy products in general was moderate prior to 2000, but increased rapidly after 2000.

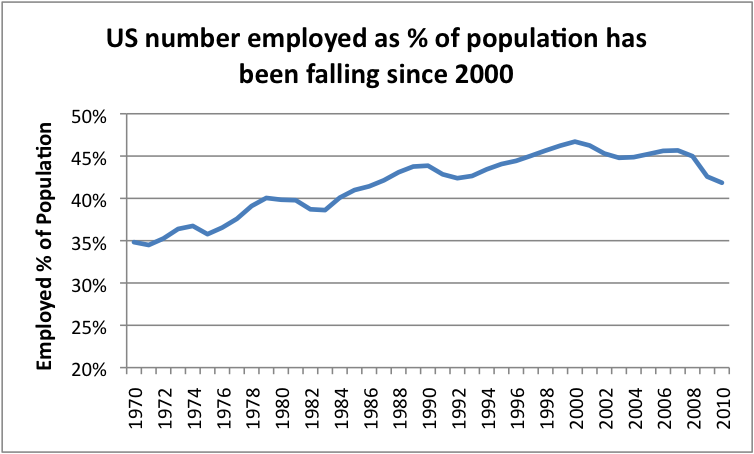

When we look at the percentage of the US population that is employed (Figure 9), it has been decreasing since 2000, so there are fewer people earning wages, and thus able to buy oil and other products. Prior to 2000, the percentage of the US population working was increasing.

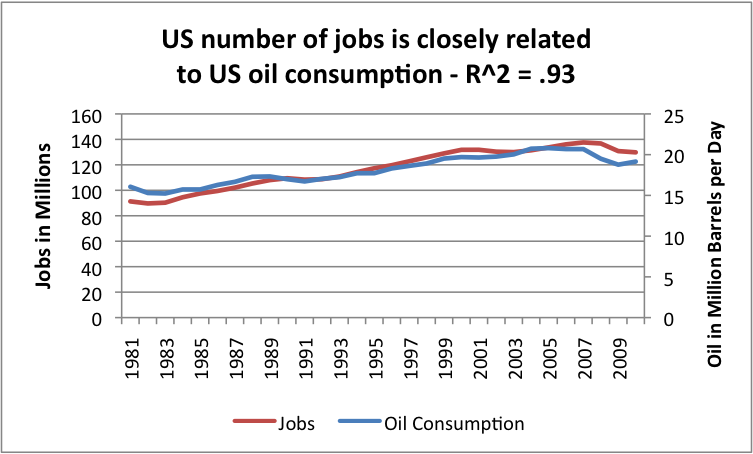

In fact, over time, in the US, there is a high correlation between number of people employed and amount of oil consumed.

This high correlation is not surprising for two reasons: (1) jobs very often involve often use oil in producing or shipping goods, and because (2) people who are earning a salary can afford to buy goods and services that use oil.

If we think about it, businesses employing people in China and India have three cost advantages over businesses employing people in the US:

1. People in China and India earn less, in large part because their life styles use less oil. As the price of oil has rises, a person would expect this difference to become greater, if salaries of US earners are raised over time, to reflect the higher cost of oil, as it rises. If the living standards in China increase, the salary differential could decline, but still might be very high in dollar terms.

2. The cost of electricity used in manufacturing in China and India is cheaper, because it is generally coal-based. The cost of electricity from coal is quite likely even cheaper than electricity from coal from the United States, because these countries are more likely to have poor pollution controls, and because the coal is extracted using cheap labor. The difference in the cost of electricity can be expected to become greater, to the extent the US imposes stricter pollution regulations, or switches to higher priced alternative power (say, offshore wind), or imposes a carbon tax.

3. Taxes and employee benefits are likely to be lower (in absolute dollars, but perhaps as a percentage as well) in China or India, because infrastructure is less complex, and because there is less in the way benefits comparable to Social Security, Medicare, etc. (This is related to the lower EROEI required to maintain the infrastructure in these countries.)

With these advantages, as trade restrictions are eased and more "free" trade of services is enabled through the Internet, I would expect an increasing number of jobs to move overseas, and more goods and services to be imported. Salaries will also tend to stay lower in the US, especially for jobs associated to goods and services that can be produced more cheaply in China or India.

With these lower salaries in the US, demand for oil in the US will tend to be lower, because people who are paid less (or out of work) will not be able to afford high-priced oil for vacations and other optional purchases. As more US jobs move overseas, unemployment and recession can be expected to increasingly become problems. Furthermore, it will become difficult to collect enough taxes from the lower number of employed people to pay enough taxes to keep the system operating. I write about this in What's Behind the US' Budget Problems?

One thing that happens, too, with this arrangement is that world's coal use has risen.

I wonder if all of the emphasis on CO2 reduction has not exacerbated the problem. Countries that reduce their own coal use and instead rely more on imports can feel virtuous, but they also set the stage for negative impacts. By using less coal, these countries leave more coal for lesser developed countries to import. These lesser developed countries probably burn it less safely (for example, with less mercury controls) and compete with them for jobs. The developed countries can be expected to have more and more budget problems, as their tax bases erode, and the number of unemployed rises.

When new electricity generation is planned in the United States, the usual practice is to compare expected costs with other types of new electricity generation that might be possible in the United States. It seems to me that this practice does not show the full picture. Goods and services produced in the United States will have to compete with goods and services produced around the world. Some of the electricity used will be from nuclear plants that have long been paid off; some will be from coal production; and a little will be from high priced new types of electricity production. As long as there are no tariffs or other trade restrictions, higher-priced US electricity will tend to hinder exports and help imports. I would vote for trade restrictions.

Conclusion

The downslope of oil production can be expected to reflect a combination of different impacts. Unless technology improvements truly have a huge impact, it would seem to me that the overall direction of the downslope is likely to be faster than Hubbert's Curve would predict.

Thanks for writing!

Best Regards,

Gail Tverberg (also known as Gail the Actuary)

File: Beyond Hubbert Presentation from the 3rd Biophysical Economics Conference, April 15-16.

Precisely one mention of political stability as a factor in the future oil supply.

I think we can see in the Middle East right now, that political instability can lead to stair-step reductions in the oil supply, and these are likely to provide very rapid positive feedback.

For example - Rebellion starts in Libya, Rebels quickly gain control of eastern oil fields. Western propped dictator dropped like hot potato. Dictator proves stronger than expected. Western alliance starts bombing tanks. Rebels start selling oil.

Dictator changes tactics. Blows up pipelines in Eastern oil fields. Oil production falls to zero. Political and military stalemate.

Global production falls by 2% in 2 months.

Rinse and repeat. Once we become desperate for oil, we will interfere militarily. It will cause rapid collapse of the oil supply.

I agree. Political stability is a big issue. It is tied to having adequate food for everyone, and with food prices rising (in part, because oil prices are rising), this is becoming an increasing large issue.

Or maybe it's in the oil importer's best interest not to interfere. If the people in charge are willing to oppress their own people to export the most oil because they don't care about anything but lining their own pockets, why in-source the dirty work? Maybe the rest of the world will just let the feudal lords of Oilvania have their feifs as long as they keep selling off the oil.

Then when it's all gone, they and their cronies can take their money and flee the depleted country retaining their dough.

Gail, thanks for an excellent post. You are a bit pessimistic but I am even more pessimistic. I think the downslope will be higher than even most peak oilers anticipate. And it will be jerky, not smooth at all.

The reasons are, I think, very obvious. First it is likely that there will be even more unrest in Africa and the Middle East than we are seeing right now. As people's living standards go down you will see far more rioting and unrest among the disenfranchised people. Destroying pipelines and other parts of the oil infrastructure will be just too easy for those who blame the more wealthy for their plight. The situation in Nigeria will get worse and spread to other oil producing nations.

Then there will be the problem of hording. I know some people say nations like Saudi Arabia cannot possibly hoard their oil because they must have the income to buy food. This is true but if the price is high enough they just don't have to produce as much oil as they have been. They could cut their exports in half and still have enough money to buy food, especially if the price is higher. And they are likely to be far more worried about their future than they are our present. They just won't care what their lack of production is doing to the world.

Then the decline percentage is likely to decline. In Mexico and the North sea the decline was only a few percent right after the peak but then it increased to between 6 and 9 percent after only a few years.

Of course there is the EROEI problem you write about above.

Then there is the shark fin phenomenon, not just that one caused by EROEI decline but caused by the use of "super straws" that are currently so popular by Saudi and all countries that have giant fields. That is they use horizontal MRC wells that keep the oil flowing at a very high rate right up until the end. They suck the oil right off the top of the reservoir and that keeps the oil flowing at a high rate right up until very near the end.

I think that is what Saudi Arabia is doing right now with their Strategic Energy Initiative where they say they have gotten their decline rate down from 8 percent to almost 2 percent. And they did this largely by just sucking the oil out faster with the aid of new horizontal MRC wells. Sooner or later, because they are depleting their fields so much faster now, the water will hit these horizontal wells and then it will be almost over.

Ron P.

You are right. There are really quite a number of issues pulling supply down, some on the supply side and some on the demand side (not being able to afford the oil), and the results are likely to result in steeper drops, here and there. We don't really know when Saudi oil supply will begin to drop off, and that could have a big impact. Debt defaults and political disruption could also lead to steps down.

This post is quite closely related to the presentation I gave at the Biophysical Economics Conference in Syracuse NY on April 15-16. Eventually, there will be a web site up with the presentation (and audio recordings of some), but I think all that is up now is the agenda.

Great post, Gail. I like summaries that gather together the threads of thought wrt Peak Oil.

On another note, this weekend, I was riding a gondola at the local Ski Mountain while watching my GPS Map (60CSx) - at first, the gondola rises up gradually, comes over a peak, and drops precipitiously for a bit before returning to its ascent. The altimeter plot looked for a moment exactly like a shark-fin version of a Hubbert curve! That got me thinking a bit for the rest of the ride - how political instability is probably the greatest threat to the undulating plateau. Instead, it's a easy to imagine how, at first, the "poor suckers" get to go without and then finally, unprecedented (perhaps not) human misery.

As Dmitri Orlov puts it so succinctly:

Closer to the orange line than the green line, unfortunately.

Great chart Dude.

"Closer to the orange line than the green line, unfortunately."

Given the close link between food production and oil, would not a orange-like descent imply an equally staggering increase in outright hunger?

Yes, exacerbating the problem is a failing financial system, spiking food prices, exhaustion of aquifers and breakdowns in international trade that will cause the famines.

My money is that overall world population begins to fall in the next decade sometime, pretty close to scenario 1 of the LTG runs:

The Great Food Crisis of 2011

http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/01/10/the_great_food_crisis_o...

Bankruptcies have limited effect on productivity of arable land, from what I've seen. Whomever owns the land; the farmer, the bank, or a trustee, will usually have the land in production. There are enterprising farmers who will lease the land and grow corn, run cattle, something. Even in times of economic decline, someone will use arable land to grow something, whether or not it qualifies as human food. The limiting factor seems to be the cost/availability of inputs vs. the land's production value.

Do you have some data to back up this assertion? It seems a stretch to me. I can't imagine banks, for instance, going through all the work of keeping land in production in the depths of Great Depression II. Why would they bother?

How much work would they really have to go through lease farm land? It's not like they'd have to send out their own employees to farm it.

The bank owned property down the road is leased, only for cutting hay, and for a minimal fee. The bank benefits in that the land is maintained (fertilzed, mowed twice a year, and they are assessed at an agricultural rate for taxes). Another section I know of is in forclosure (I knew the previous owner), several hundred acres, and has been planted in corn for the last 2 years. As I said, not always human food, but good farm land doesn't stay fallow for long around here.

As for statistics, I'm not sure where one would look to ascertain the ownership status of arable land vs. its production.

That's not the point. If commodity food prices aren't high enough there is sometimes no point in planting. Yes, I do think that in a severe enough contraction we might have a temporary surplus of food and not enough people with money to buy it.

A bunch of monkeys controlled by magical price points that mean nothing and everything at the same time. Aren't these price point pressures supposed to lead to all kinds of cool stuff. It's seems like they make us stupid.

Maybe that should be a requirement, and they should be given hand implements...

During GDII the banks may have a considerable incentive to keep land in production;in the trhirties , there was little or no incentive, due to glutted markets and depressed farm commodity prices.

Taxes were very low then.

This time around, there will be few or no farm commodity gluts, and local and state govts are likely to find creative ways to make sure banks lease any land they hold to farmers at very cheap rates.

I haven't given this particular issue any extensive thought, but I suppose a county or state could find a legal way to tax the hell out of idle farnm land, while rebating most of the taxes on land in cultivation , for example.

Or a populist govtr takeover might solve the problem by forcing the sale of the land at dirt cheap prices to locals.

I hope you're right! For one thing, we'll need something for the hundreds of millions of unemployed people to do and farming could "soak up" a lot of those people.

OFM,

There is a downside to this of course.

IN my years around farming I have noticed that the care given by someone farming leased land is very seldom of the quality one would expect of an owner. Even when the owner of leased land is knowledegable about proper farming practices the person leasing often cuts corners or will do things that he would not do to his own land. An example of this is one of my neighbors has a 2nd farm about 100 miles from us. He leased the land out for corn production to one of his neighbors down there. On a visit last year he found HUGE ruts (2 feet deep) where the guy leasing the property had brought his equipment in when the ground was to wet. Messed up a bunch of ground. The place across the road from me has been leased for hay production for 15 years. The owner knows nothing about farming. Only once in that entire time has the land been fertilized and it has a huge percentage of weeds. The norm is only to get one cutting from it. ONe often sees much greater problems with erosion and poor irrigation practices as well.

Just saying that, whiole you are likely correct on the land still being used, there are some bad long term implications for such a situtation.

Wyo

I am not a farmer, but I have seen this anyway. Leasers are not owner. As simple as that. This is also the reason comunism don't work.

One big reason for keeping land in production is to generate rents or other income sufficient to continue paying the state property taxes on your land - thereby avoiding eventual seizure/auction of said property by agents of the state (at gun-point if needed). At least this is the civic wisdom behind property taxes that is sometimes argued in Economics 101 courses.

Now, aren't you ashamed of yourselves for assuming that it was all about common greed? ;^)

I agree that bankruptcy has little affect on the SHORT TERM production value of the land, but beyond that I would have to disagree. Temporary leasing

of the land to "enterprising farmers" tends towards using the soil as a medium for growing a crop and capturing the solar gain. At the minimum there

is a major impact on organic material in the soil. In fact I could generalize this to any temporary leasing.

Land that used to be fertilized with formerly cheap fertilizer will not yield the same output per hectare as the same piece of land being opportunistically exploited by some random successor to the bankrupt farmer.

In terms of Tainter's theory, a system brought to its breaking point by increasingly costly complexity will eventually exit the complexity treadmill via a collapse event. When that happens, by definition you no longer have all the outputs of the former system. But at least you have a form of stable dynamic equilibrium.

The same applies to the post's question about the speed of the oil decline. So far the decline has been slow and masked or compensated for by other low EROEI liquids being added such as biofuels, NGL, tar sands, deep water oil. We kept up the total liquids supply and dealt with that stress at the cost of stresses to the food and financial systems which had spare capacity to absorb stress. As the latter run out of capacity to absorb more, the stress is spilling over into the political and social systems.

If or when the total stress exceeds the total ability of the system to accommodate, the system shifts to fast decline mode. Libya's oil output over the last three months is an example of all the above.

You have good way of explaining things. Thanks!

Yes, very well expressed!

Thank you, I try, but the old adage of a picture being worth a thousand words probably applies here too:

This Youtube video of a Windmill/turbine going wild and finally break (sic) probably does a better job than I ever could of driving home the notion that catastrophic collapse is the most likely failure mode of complex systems.

Is there any system more complex than our global technological civilization upon which 21st century oil extraction depends? I don't believe so.

To borrow an analogy from the wind turbine video, when we tapped ancient sunlight in the form of fossil fuels we finally "broke the brakes". We've been spinning our blades faster and faster ever since.

Have we ever:

Historical Consumption of Various Resources and Other Factors Plotted Against Time

(Click to enlarge.)

Of course this ends in collapse when a system is put in this much stress.

P.S. I don't have the source of this graph so if it belongs to someone who is reading now please let me know.

Highly doubtful. It would really have to be a very concerted effort to kill off hundreds millions of people for the population to fall that quickly and would not be from lack of materials but a complex structural issue. Hopefully we don't chose to do that. It could happen, but we would have to try really really hard to keep the same resource distribution system running. Which is one of waste and misallocations.

My money is on quick economic collapse and hopefully some semblance of sanity in how we manage resources afterwards. But we all have our collapse fantasies

Sorry, highly doubtful that the LTG Scenario 1 would come to pass?

I view it instead as certain that population will decrease, given the reasons I stated above, and the question is only whether it will be slow or sudden.

The alternative, that we reach a stable state, is impossible — it ignores too many factors, like exhausting our aquifers, depleting our ocean fish, acidifying our ocean and other climate changes, destroying our biodiversity and of course depleting oil, that make that condition impossible.

And the other option, that we continue growing, is logically absurd, in my view. Only someone who has very little idea of the state of the planet and ecology (i.e. an economist) would consider that as possible.

aangel,

Just to reach zero population growth would require someting on the order of an increase in the death rate coupled with (if one could get it to happen) a decrease in the birth rate which together totaled something like 80-90 million a year.

This is a large number and to put it in perspective. During the worst death rate in modern memory (i.e. WWII) population growth barely was even effected.

I agree that there will be a large decline sometime in the future. But what form it takes is hard to say. My guess is that population will continue to climb for some time. Maybe another 20 years. I believe that there will be serious efforts to maintian BAU. Hurculean efforts even. Then it will all fall apart when it can no longer continue to be maintained no matter what is done. Climate change and peak energy will eventually overwhelm everything. But what do I know.

Wyo

Agreed...I see another 15 years of population growth, too, even with some rather nasty regional wars that are likely to occur as we fight over declining resources.

Could be, but compare these bar charts:

http://www.indexmundi.com/world/birth_rate.html

http://www.indexmundi.com/world/death_rate.html

The birth rate seems as if it could be at the beginning of a curve of accelerating descent, while the long term decline in death rate seems to have stalled out and is predicted to start rising in the next few years as the boomers start to go.

Of course, even of these nascent trends could stall or even reverse for a while, but trends of the last two or three years could put us at peak population in a decade or so.

Even if it jumps a little bit at first, the human race so deep into overshoot there's no way to go but down, and fast. I think the initial spasms of massive numbers of deaths will be in the Bay of Bengal vicinity and also in the overcrowded islands (Indonesia). It'll be of all sorts; infant mortality, lack of elderly care, resurgence of diseases (dysentery, etc.), lowered life expectancy, inability to care for injuries, revolution, fundamentalism, etc., etc.

This will all be revealed in time on your favorite news channel (unless you're already there).

Already now we eat more food than we grow. World inventories are going downwards. Using current trends, it will be down to zero in 10 years. But expect a faster run to there; in those 10 years there will be added another 850 million hungry mouths. And all the depletion issues to that.

When we are out of food stocks, what do you think will happen when there is a drought and consequent famine? No one will have any spare food to send. So we will have no options to letting them starve. It will be back to the medevial ages when the Grim Reaper came and harvetsed entire fields. Only thing lacking to make the image complete is a new deadly patogen we can't find a cure to.

Exacerbating these trends are of course increases in meat eating, bio-fuels and extreme weather events. The first two we have some near term control over. The third we are making worse with every extra molecule of CO2 we put into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels.

On the other hand, the middle ages weren't all bad '-)

And add UG99 to the picture. Google it, it is an interesting read if you have not heard about it before. Once a year I check out it's progress.

Andre (angel),

By the way, are you aware that the LTG authors say that whatever predictive value their models have only holds up until the downslope begins? (Page 142 in original LTG book) Their point is that the models they have put together are based on a growing world and rising resource use. They have no way of knowing how things will change on the downslope. For example, will women have more or fewer babies? Will there be breakdowns in supply chains that affect production more than the models would indicate?

I think they were trying to leave the door open for the downslope to be better than what was projected, but it is easy to see how things could work together to make it worse.

I wasn't aware of that...I have their 30-year update and I don't remember reading that (but could just have a faulty memory).

Yes, it all comes back to how complex systems fail, I think. They don't include that in their analysis. Their program assumes smooth transitions i.e. it doesn't know how to model complex failure modes.

I bought myself a used copy of the 1972 book, so I could really see what they said.

I don't think that they wanted to be more negative than they had to be--that is why they left the door open to things being better. But I think in fact the models are quite optimistic, because of many things they left out, like complex failure modes.

With respect to optimism, there is also a "steady state" model that they talk about. Essentially, it flattens out the amount of resources used, so that they last until 2100 (but not beyond 2100). In order for production not to fall greatly when they drop back in resource use, they must assume that something like nuclear can be used to keep production up--but I didn't explicitly see that assumption. Perhaps I missed something. I am also not sure how they deal with the declining EROEI issue. Declining EROEI would seem to mean that net resources would need to be flat, but gross resources used would need to scale up until 2100, then drop to 0. The number of babies permitted in each year would be equal to the number of people who died that year.

I am not convinced that the steady state model would have worked back in 1972. Now we don't have the extra resources to flatten out to use in future years, so the idea wouldn't work.

Obviously a steady state at anything like the current rate of resource extraction and environmental degradation is impossible.

After a vast power-down, pop-down, and consumption down, something like a steady state may be possible, unless runaway global warming and/or widespread nuclear catastrophes make much or all of the earth uninhabitable.

I think the one true steady state that the world has had was during the hunter-gather period, lasting through ice ages and extending in some places up to close to the current point in time. The hunter-gatherers, when they got too good at it, wiped out the big animals in their areas, so even they behaved in a way that extended beyond a steady state.

We have had an unusually stable climate in the last 10,000 years, and people were able to set up farming, allowing for a much higher population density. I am not sure that this has ever truly been steady-state though. (See this post, saying that the author believes the world population has been in overshoot since 8,000 BCE, because agriculture is basically not sustainable.) Population density gradually increased, as people improved on agriculture and more recently, since we have found ways to use fossil fuels to make agriculture more efficient.

It would seem to be possible to go back to a hunter-gatherer steady state, over quite a range of temperature fluctuations. What is not possible is to expect today's industrial agriculture (with its hybrid seed, developed for a particular climate and particular pests) to continue forever. We would like to think that there is a way of controlling climate / pests / energy supply, so that we can continue to dominate the world, but it is not clear to me that there is. The story that we can seems to be part of today's mythology. Maybe we can go back to a more limited agricultural society--we don't know yet how things will work out.

Edo Japan is an oft-cited example..

I've always said the same: "We went wrong after the hunter-gatherer stage". Hunter-gatherers share.

You should visit those times. Just a visit, nothing like privation or ordeal, just getting out, getting away. I went camping for ten years, bit extreme, but one week does not make a place "home". Had a great time. It's beautiful and free. Gathering wood and fetching water feels real. Walking down green paths arched-over by tall trees, dogs running free, the local animals getting to know you and coming to visit everyday: an illusion as close as one can manage. Keep dry in a nice "little house" of some sort with a wood-stove and a safe chimney. Have a cellphone. Take some friends. Drive a car. But just wind it all back for a while. If a trail beckons further, bud-off a simpler camp that lets you be there, too.

My two favorite anthropology shows are "The Western Tradition" PBS by Eugen Weber, and "Faces of Culture" PBS . Weber's narratives are illustrated with images of artwork. They explain so many of the things we are born into and simply accept; money, civil law, and military protectorates as examples. Faces of Culture takes a concept and illustrates it with examples from many different societies. They are available in libraries, at Amazon, and are sporadically posted as courseware.

The Western Tradition opening theme with credits:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s9uJOsREJC4&feature=related

just the artwork fullscreen:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HXszL_qwnGg&feature=related

I certainly agree that industrial ag is not sustainable nor frankly anything remotely resembling BAU.

I don't pretend to know everything about every society that ever existed and how sustainable they may or may not have been. I seem to recall that archeologist Colin Renfrew had identified a number of cultures who remained mostly peaceful and sustainable for centuries to millennia.

Pre-Greek Balkan societies were one example from archeology of a fairly advanced culture (indoor plumbing, art, beginnings of writing) that lasted a few millennia.

Perhaps the lack of EROEI consideration may be a result of great optimism of the early 70's - (I was an optimistic kid) - nuclear power generation a greater but yet to be reckoned with force (pre-3-mile), and so on.

We know more now, that we'll be hard-pressed to discover something fundamental to further propel us into a Sci-Fi technofantasy that will never occur because we've nearly exhausted all our momentum and primary resource. I don't think anything's going to pop out of the quantum foam and reveal a savior of sorts!

Moore's law is kaput.

The Kurzweil Singularity is still decades away (if it ever happens).

Nuclear Energy isn't the panacea that it was supposed to be (in the 70s), though it certainly has its share of interest.

Even the planes flying today are still fundamentally identical to the ones flying in the 1950s, just bigger and faster.

Even the planes flying today are still fundamentally identical to the ones flying in the 1950s, just bigger and faster.

Actually, they are not any faster.

If you look at the Hawker Siddeley Trident 2E, it had a cruise speed of 604 MPH (972 km/h) and was introduced in 1964.

The latest Boeing 747-8 which has yet to enter production has a cruise speed of 570MPH (917 km/h)

The A380 is somewhere in the middle of the above.

If you look at the Concorde and why it was a commercial failure (like the Trident), you will understand why planes have been slowing down.

I need hardly add that passing through an airport takes a multiple of the time it used to take when I was a kid and travelled regularly on Tridents.

We had a chance to develop 4:th generation nuclear power, but when Chernobyl happened, the momentum was lost. Now I doubt we have enough time. 4:th generation nuclear would have been a neccesary step towards techno-fantasy, but now I think we will miss the train.

If you were obscenely rich

and wanted a remote enclave

would you choose nuclear

or natural flows and fluxes

or find your own pocket of gas?

The nuclear needs high-rent staff.

It's failure modes are unattractive.

The enclave could become dark or deserted.

Electric transport or convert CO2?

Gathering wind and light takes more room.

A mountain lake is needed for storage.

Wind and thermal engines need rebuilding.

Electric transport?

Gas engines need rebuilding.

Logistics can run on gas directly.

(There is lots of gas in Alaska.

It's supposed to be getting warmer?

Or will it much more be getting stormier?)

Hmmmmmmmmmm

"hmmmmmmmmm

could be the human race is run"

-Pink Floyd Two Suns in the Sunset

I don't have a reference handy, but somewhere they stated exactly the opposite. Their scenarios are actually extremely optimistic because there is no accounting in the world model for war, revolution, genocide, terrorism, or any of a number of other less than favorable human reactions to the unpleasant ecological realities.

Cheers,

Jerry

Not hunger. Death by starvation.

Not necessarily, because only a small portion of oil goes to food production, so we would have to chose all are other allocations to stay the same and oil allocated to food production to decrease. So it's a choice.

I don't think it is really a choice. There are a huge number of supporting oil allocations that need to be in place, to allow oil to go to food production. For example, the roads need to be maintained, someone needs to be making spare parts for the equipments, someone needs to be making the fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides, and there has to be a sufficient transportation system in place to ship all of these. There needs to be a system of distributing the food, and the electrical system needs to be kept operational, so that fuel can be transported by pipeline and pumped from stations. People need a way of getting to the places where food is distributed, and they need money to buy the food (or food stamps or some other allocation method).

So I don't see that keeping the food system operating is all that simple. If you start having allocation problems, people will go to the fields, and steal food from the fields, and the whole system will break down.

...feed for animals, packaging, processing, refrigeration, marketing ...... there's a lot of oil in our food. Witness the rising costs of food as oil prices rise.

This year I'm moving a good portion of our gardening to containers. This frees up the big garden for field grown crops; corn, onions, grains, etc. It also: gives me better control of soil mixtures; saves water; reduces exposure to the huge downpours we've been getting (erosion from water/wind); and since I'm growing stuff on the roof, it helps keep the house cooler. This is an experiment designed to see how much we can grow with minimum fuel inputs. Solar pumped drip irrigation, (very) locally sourced fertilizer, mainly from our chickens and compost, soil from my 'stockpile' which gets recycled into the compost pile, and having a portion of our production so close to (on) the house will increase food security and reduce the energy we expend for harvest. We are also growing potatos in used feed sacks. Last year, the super pigweed took over the potato patch, really cutting production. My buddy grew over 200# of nice potatos last year in 8 feed sacks. Not bad for an old hippie.

These may seem like small steps, but that's how it's going to work for many, IMO. The ideal is to grow most of our food with zero fossil fuels.

Nicely done!

From this article a pound of potatoes provides 400 calories.

200 lb x 400 cal/lb = 80,000 calories

Assume 2500 cal/day for a male (more if physical labor is part of the day but this is a start).

80,0000 cal / 2500 cal/day = 32 days worth of food.

Now, you wouldn't eat just potatoes but it's still a good amount of food from just 8 feed sacks!

What do you figure it cost your buddy to produce 32 days worth of food?

If he bought his seed potatos (5 per feed sack, maybe 1/2# total) about 65 cents, old feed sacks (free, sort of) homemade soil/compost (free, with labor). About 65 cents.

If he used chemical fertilizer (unlikely), add a couple of dollars. If he saved seed potatos from the previous year and used homemade fertilizer, no money exchanged hands. This would be his style.

This is a really easy way to grow a staple crop:

How to Grow Potatoes in a Garbage Bag

Once the plants are established, straw or dry leaves can be used to fill the bag as they grow. Anyone with a bit of space in the sun can do it. Some folks go out and buy bags of garden soil and grow right in the bag. The giant black contractor bags from the big box stores also work well, but I plan to use feed sacks saved from our chickens.

The potatos can be left in the sacks until use, in a cool, dry place.

Disclaimer: I do keep a stockpile of chemical fertilizer (10-10-10) that I got cheap last year. A little goes a long way when combined with our organic stuff (usually not needed unless a plant needs a boost). It could be useful for barter if we don't need it. Nice insurance/capital when one is starting from scratch, as I suspect many folks will be forced to do.

I have trouble with gophers, etc, , so I will a stack 3 or 4 old tires placed on hardware cloth.

Ghung, are you recycling the fertilizer you and your family produces as well? Lots of usefull atoms get flushed down the toilet if you don't.

I've put low raised beds above the septic drain field, so, in a sense, yes. Between my wife and building codes, a composting toilet wasn't an option when we built. I "mark my territory" regularly to deter predators and varmints, returning some nutrients to the soil. If things get tough you can bet that a humanure processing system will be a priority ;-)

Our codes wouldn't even allow a gray water system when we built (mid-late '90s, though I did pipe the gray water separately).. Not sure if that's changed.

"Our codes wouldn't even allow a gray water system when we built (mid-late '90s, though I did pipe the gray water separately).. Not sure if that's changed."

These are hings we will ave to change by doing and drag the codes along. Community becomes important when it is necessary to take a stand.

Excellent work. his is exactly the kind of thinking we need to apply to the problems at hand. Old wisdom coupled with scientific knowledge is an extremely powerful combination.

Food production worldwide has changed hugely in my lifetime - I turned sixty four months ago. When I was a boy mixed agriculture was very common where I live (eastern England) and the relatively small fields resulting from the enclosures of previous centuries were bound by high hedges. These both contained animals when the land was fallow and prevented wind blown topsoil erosion. Chemical fertilizers had already been introduced and already mixed arable farming was beginning its decline. Many more men worked the land then, however. Gradually hedges were uprooted to make way for ever larger machinery and monoculture dependent on 'improved' fertilizers and seed strains became practically universal. Now topsoil erosion is a reality and there is very little biomass or animal waste plowed back into the soil. The soil has consequently been reduced in some areas to a practically lifeless tilth dependent on artificial feeding. All this is the result of oil dependent agriculture. You can add in the pesticide revolution to complete the picture.

I know of one village (it can be replicated almost indefinitely) which had three farms employing seventy men in all before the war, now all those farms have gone and been absorbed into one much larger unit, and besides the farmer only two full-timers are employed. At certain picking seasons and for particular crops labour from Eastern Europe is employed, and gang-masters keep them in hostels and often treat them badly. The village cottages are now inhabited by town dwellers seeking that 'real' country experience and they commute fifteen miles each way to work, by car. The village post office and shop closed years ago and shopping has to be done seven miles away. The ancient cattle market in my city has been rebuilt as a shopping mall and many young people have no idea what a cow looks like.

All the brick-built barns have been converted to houses and the new industrial barns are fed and emptied by monster trucks. Nobody has a clue how to work with farm horses and anyway their stabling is long gone.

Reversing this situation will I fear be far harder than creating it, although some farmers are planting hedges again. And meanwhile the population has increased by a third.

The price of energy is having an effect, now, and I fear for what will happen in the very near future.

I have nicked, or rather gleaned, remaindered carrots left behind by the harvesters from the field, once, when I had run out and I was taking the dog for a walk, but if everyone came and took the farm produce there would be no incentive to plant again and it would consequently happen only once. Already farmers are having Diesel oil and machinery stolen and in some places sheep are being taken.

If oil supplies reduce quickly, or rather the price increases quickly, then I agree with Gail that maintaining food supply will not be easy. The horses are all gone, the appropriate equipment is in museums, and the infrastructure is blown to bits. And the resultant crops would be more dependent on the vagaries of the weather than now, I suppose.

I would expect that when the situation becomes serious all our ancient notions of land and indeed all property ownership will be called into question. Do not expect the free market to solve the problem in a hurry.

Apologies for the long waffly post.

No need to apologize it's a good post. The situation in Spain isn't quite as bad as you've described. Most of the old farms are fallow but there's a few old timers tending to their vegetable patch. In my mom's old village there's still a residual level of agriculture going on supplementating the diets of farmers on pensions. A few people still have a few cows and pigs, everybody has chickens and a vegetable patch. There's plenty of animal enclosures. A few city dwellers have bought homes in the area but they're in the minority. If worst came to worst it wouldn't be a bad place to be.

Brilliant description of the problem. How to reverse this is, I believe, the difference between uncontrolled collapse and controlled power down.

It's a conversation needs having.

"someone needs to be making the fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides"

In all scenarios, it is extremely important to remember these are utterly unnecessary for feeding the planet, but that land reform will be.

Agreed!

Gail, and everybody:

For some reason, modern fertilizer sources, methods and results have become arcane, obscure bits of knowledge outside of the communities directly involved. I don't have the details or statistics but at least I can present the general themes. First of all, far and away the most volume of the three types, nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus fertilizers, are nitrogen. Second, far and away the largest volume (++95%) of nitrogen fertilizers are manufactured by the use of natural gas, in fact, I believe as much as 40% of ALL natural gas produced in the world today is used to manufacture nitrogen fertilizer. Finally, since the advent of this massive production and use of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers around 50 years ago, the yield per acre of good farmland has more than doubled.

Peak natural gas is not upon us yet, but it can't be too far away. What then, Kimosabe?

Thanks for this detail. I for one count natural gas along with oil as an irreplaceable hydrocarbon. I know that since the advent of fracking every square mile of the earth's crust to smithereens to extract every last puff of the stuff we are told that reserves of NG are practically infinite, but I am not convinced. Also, the price of nitrogen fertilizer has ramped hugely recently so all that blasting needs to be accelerated! It does seem that now, however, some lucky consumers can now get gas free from their water taps, which has to be some sort of progress?

I can't help being cynical, but natural gas is as finite, or rather differently finite, as oil, so the basic thesis tends to hold.

And yes, agricultural land is getting more expensive by the day, but then it too is finite in a world with an expanding population. Or is it in fact diminishing in area?

Yep: peak gas, and peak pretty much everything really...

The rate of decline in the cost of PV has been too slow for the blue line to be realistic.

The only reason for optimistic at this point: necessity is the mother of invention. But is it the mother of enough invention?

If the world were a replica of the United States, that sort of pessimism could perhaps be justified. The rest of the world is not as far into overshoot as the US, though, and their political systems are, on the whole, not so dysfunctional. I think the green line is more likely, on the whole, though not quite the controlled process as implied by its title of "creative descent". There will be stumbles, partial collapses, and frequent application of the principle that "necessity is the mother of invention". Since renewable energy technology is already available, though, the descent into the Mad Max scenario is likely to be avoided.

On a somewhat different topic, Darwinian above said:

This makes the error of assuming a commonality of interest between the House of Saud & its subjects. We're talking here about an absolute monarchy which has nothing but contempt for its subjects and refuses to allow them the meagrest of freedoms. It needs backing from overseas (especially, but not entirely, in the form of weapons) to keep its subjects down. Therefore it cannot afford to cut off the supply of oil to its overseas sponsors.

The House of Saud was installed as ruler of the country named after it by Britain, at the end of World War I. After World War II, the US took over as overseas sponsor and supplier of weapons. The US is now on the way downhill (the negative ratings watch on Uncle Sam's AAA debt rating should be the wake-up call to the world) and the possibility exists of China taking over at some point. I note with interest the fact that the Saudi Government is improving its relations with China, so it would be unwise to rule this possibility out.

The bottom line, though, is that the House of Saud would lose its usefulness if it stopped supplies to its overseas sponsor and would be cut off. It would then have to face its subjects alone. And, considering the barbarity of its teachings to those subjects, its fate would be unlikely to be pretty.

Most think Saudi is already hording its oil so if they do have even one barrel of spare capacity then what you say is already proven untrue.

What Saudi is claiming to do right now is that they are cutting off oil from their overseas sponsors. They say they could produce 12.5 mb/d right now if they only wished to. They are telling their overseas sponsors that they are cutting off at least 4 million barrels from them.

So your claim doesn't hold water.

Ron P.

What I said was:

Saudi Arabia has not cut off supplies, but merely reduced them a little. And Obama has agreed with them that the world is "amply supplied": http://green.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/04/22/saudi-cut-in-oil-production-st...

If I gave the impression of believing that the House of Saud is merely a puppet of Uncle Sam, I'd like to withdraw it. They have interests of their own and some autonomy with which to pursue them. What they don't have is the ability to hold their number one sponsor to ransom and get away with it.

In the words of the book "Limits to Growth":

I think the fact that the Peak Oil groups have tended to place so much emphasis on something that intuitively doesn't happen is a big part of why people don't believe the story we are telling. Nobody wants to explain that we are getting close to the edge, and the downslope doesn't look nice.

Just dreaming a bit, but wouldn't it be great if there was a building that housed to scale precisely accurate translucent views of the oil reserviors of all the major oil producing countries. And with that view we could see how far up the water is, and then based on flow rate determine when each well will tap out. No more asking the saudis, just look for yourself. Would probably scare people so much they'd have to close it.

Wow. A good, cut-to-the-chase question and a good, solid answer.

I've been following the peak oil issue and its ramifications since 2002, and I still have the same question that Curious did. Early on I was expecting serious problems to begin around 2010. Its interesting that it is still arguable whether they have in fact begun. I think a lot of us "early adopters" have become mentally and emotionally worn out with the long-term nature of the problem, and with constantly trying to answer this particular question.

This article presents an excellent summary of the reasons it is more likely to be faster than slower. I still haven't found anything that presents actual time-based scenarios that are convincing and helpful in terms of preparation.

Some time-based scenarios that some may find convincing and helpful in terms of preparation:

http://www.energybulletin.net/stories/2010-10-18/peak-oil-versus-peak-ex...

Peak oil versus peak exports

http://www.energybulletin.net/stories/2011-02-21/egypt-classic-case-rapi...

Egypt, a classic case of rapid net-export decline and a look at global net exports

From Peak Oil Vs. Peak Exports:

Certainly, the rising consumption of oil exporters is part of our problem. Even if there were no other influences, from the point of view of oil importers, the down-slope could be expected to be steeper than the upslope.

It's not just rising consumption that is the problem. Given a production decline in an oil exporting country, unless they cut their consumption at the same rate as, or at a rate faster than, the rate of decline in production, the net export decline rate will exceed the production decline rate and the net export decline rate will accelerate with time. And of course, as outlined above, then there is the Chindia factor.

I do think that the ELM provides the most convincing time-based scenarios. I see no way in which the decade from 2025-2035 (my 50's) will not be extremely difficult for those of us in Importistan.

"Importistan"

Nice term. Your coinage? (Apt for "consumer" which we all are.)

Westexas

It is difficult to get ones head around what is happening in China, the first year they sold over a million cars was only 10 years ago. I have no idea how far back you have to go in the States for that level of sales 1920?

Yet this year they will sell over 16 million cars.

http://factsanddetails.com/china.php?itemid=314&catid=13&subcatid=86

That coupled with increasing populations and consumption in OPEC countries will continue to add pressure on exports.

It's fairly simple to figure out what is happening in China. Twenty years ago, they were consuming less than 3 million barrels of per day and were a net oil exporter.

Today, they are consuming 9 Mb/d, and importing 5 Mb/d of it. Their imports are rising by 1 Mb/d every year, and with the number of cars they are buying, that trend is likely to continue.

They are now importing about half as much oil as the US does, and if it keeps growing on the current trend line, they will be importing more oil than the US before the decade is out. World oil production is not growing to match that demand.

Almost all of the cars the Chinese are purchasing are additional vehicles on the road and not replacement vehicles as many in the United States are. Their usage has nowhere to go but up.

In the financial crash of 2008 the Chinese and Indians "stole" a hole bunch of our oil imports. Millions of barrels a day that used to go to us (US/EU) now goes to them.

I fully expect a repetition of the crash after the summer (unless the fallout from Japan + tsunami gets us first as Kunstler believes) and then Chindia will take another chunk of our imports. And they will never give it back. This may very well repeat it self a few times over as long as there is anything to import.

Thanks, Gail. To this list ....

...I am compelled to add the proverbial external and always unpredictable event, refered to by some, of course, as the "Black Swan".

Whether complex systems have a tendency to crash rather than decline slowly is a basic question we often discuss on TOD. My belief is that they do both, sometimes simultaneously. During the decline (a precursor or subset of an impending crash), the system becomes more brittle or vulnerable to a crash. IMO, we tend to discount unpredictable events over time, and ignore increasing complexities in our systems in exchange for the ongoing benefits being realized from the success of the systems. Over time, while the possibility of a certain event may not increase, the range of events that may become critical increases over time. Therefore, the opportunity for a slow decline diminishes, oportunities for a crash increase, and the effects of the crash become more severe. I think the Fukushima situation is a prime example.

My sense of things is that our complex systems, including oil/energy, have passed beyond the critical point where a slow decline, managed or naturally occuring, can occur. The systems have become too complex, too interdependent, too neglected, overexploited and insufficiently resilient.

Hummingbirds will soon qualify as Black Swans.

I think there is a possibility of collapsing down to a less complex system. Perhaps the federal government will atrophy or disappear, and the states will issue their own currencies. Of course, if this happens, international trade could become a more complex issue.

I'm not sure; I suppose it depends on the nature of the collapse. Is a group of nationstates, each with it's own currency, laws, govt. a less complex system? Is the Fukushima situation less complex than it was before the quake/tsunami? Perhaps complexity doesn't just go away, it morphs into chaos. In cases of catabolic collapse, over time unsustainable parts of systems are discarded in a series of steps (ala Greer, et. al.). Incremental reduction in complexity is certainly preferable...

Even in a managed scenario, human systems seem to have a problem decomplexifying. I've worked toward reducing complexity in my life, though it seems I often exchange one form of complexity for another. My home's off-grid electrical system is far more complex than my sister's electrical system, though she is reliant on a far more complex system overall. Our attempts to replace fossil fuels with alternatives also result in increased overall complexity, a sort of trap driven by expectations.

Is it inevitable that there's a natural law that says the only way to dissipate the stored energy in our complex, maxed-out systems is an explosion of chaos, or can the system be powered down in a controlled manner? Timeframe is critical to these questions.

I think Joe Tainter would consider adding layers of administration more complex, and removing layers of administration less complex. So getting rid of the federal government would in some sense make the system less complex. There would be less $$ required, since social security, medicare, and all the federal government mandates would go away, all at once.

The "smart grid" is definitely an example of a more complex system that folks are considering adopting, in the hopes that it will help mitigate an electricity shortage, and help work our way around undependable wind and solar electricity supplies. I think it has a very good chance of making the system more prone to collapse.

In a sense, China and India's use of coal, without very good pollution controls, is an attempt to use a simple, cheap, less complex system. OECD has tended to go the opposite direction with its high tech wind and solar PV, plus the carbon market.

I wrote a post not too long ago on Our Finite World, telling what Obama should have said in his energy policy speech. The idea was to work toward simplification and local food production.

So, through your eyes I see a very serious "race to the bottom". The competing countries with the lowest standard of living, the most streamlined governance, the most capable population, and the least regulation of resource exploitation win. With the doors open to this lower potential, the higher lifestyles are rushing out of the more affluent homelands. The corporations have already bolted through and range the world. The world has flooded in.

The local industrial and economic decline has already been fast. Viewed in isolation, things appear grim.

Other nations stand ready to step in with trinkets and trade goods to sell to the newly impoverished natives of states in decline. Land will be purchased. The remaining resources will be exploited under new management. These transactions may blur the event's edge.

It is already known that the oil itself will retreat asymptotically into poor levels of return on investment. The full decline of civilizations are also known to take a long, though at times exciting, course.

I'm going to go with a slow decline in the world's oil supply and of some homelands. The rising-edge of population is dramatic. The falling edge has too many variables to predict.

___________________________

1915 technology is quite something. I have some pieces at the 100' telescope on Mount Wilson, Hubble's original. The telescope itself is the size of a city bus. Its pivots float in mercury. The supporting floor looks like a concrete overpass from the '70s. The mirror is made from old champagne bottles from France. The dome rotates on railroad tracks. The control relays for the motorized viewing-chair platform and shutter-opening means are mounted to tall marble slabs in lieu of the yet-invented plastics. There is a great, deep well in the basement where the heavy clock-weights ran to power the tracking of the stars. Everything was packed-in by mules in the beginning. This past century of technology will have some reverberation in the future.

I think you are confusing social complexity with personal life. In a complex society, more and more specialisation of roles occur, but each role can become more simple. Technology then fills the gap and makes each role complex again.

Putting the process into reverse does not work well, as we try to become baker, plumber, electrician, father, web designer, sewage engineer, teacher, etc, etc. Each role is far more comples than it was a century ago. We become overwhelmed.

Sooner or later many of these roles will fall by the wayside. Technologies will become lost. Life will become a lot less pleasant and shorter.

Who will protect the rich people from the poor if the government collapses? I mean that's it's job.

Here's what Adam Smith said:

Nobody, hopefully.

I wonder if public displays of wealth will get to be more of a problem. For example, solar panels and electric cars, if the electrical system is still operating. You see big fences in poorer countries. We may need these here, too, but I don't think that we will have the materials to build them.

I took a walk in the beuiful spring weather the other day. There I passed a very rich mans house. Or shall I say "palace"? "Mansion" is not enough to describe it. And the garden was hughe. I saw tha man there too. He sat on the veranda on the second floor, guarding over his territory. He was wearing a "cowboy hat". (This is in Sweden).

The entire garden was lined with a almost 2 meter high black fence (or rather palisade). There were surveilance cameras and signs informing about the security firm garding the house. This was just not the guy I would just walk up to and knock on the door for a chat.

Pile up wealth, fence in and insulate, live for your self. Thats the way to do it, if you are rich. When the collapse come, will I run to him for help? Will I offer my help to him? I hardly think so. When money is useless, this guy will be on his own.

The event gave me some stuff to think about.

Nice post Gail. I think Hubbert was using fission nuclear, but hoping then as we all continue to do now, for a fusion breakthrough. His fossil fuel curves would have been acccurate if nuclear had been safely developed as he anticipated/hoped. Alas, they have not been. If there is an economic-societal crash coming, a big one or even a series of smaller ones, then one hopes that the folks in charge of nuclear safety have a plan for long-term fuel storage in any event(s). Somehow I doubt that they do, e.g., Fukushima, and then the nuclear legacy becomes a potential nightmare scattered at various points across the globe.

Hubbert actually changed his mind about nuclear, due mainly to what he saw as the lack of accounting for the costs of waste disposal and de-commissioning plants:

http://mkinghubbert.wordpress.com/2009/03/08/hubberts-early-take-on-nucl...

Cheers,

Jerry

I have written several posts about the nuclear issue:

Is loss of electricity a risk for spent nuclear fuel?

Nuclear Options Going Forward

What would happen if we discontinued nuclear electricity?

Why oil shortages may make nuclear a less viable option

One thing a person needs to keep in mind is that there is a huge amount of nuclear electricity in use now. On the US East Coast, nuclear energy amounts to 30% to 35% of total electricity. We are likely to have major electricity problems, if we fail to renew licenses on existing aging nuclear power plants. This could easily push the downslope to be more steep.

There are other ways we could lose nuclear electricity--not being able to supply enough uranium for existing plants, because of oil issues could be a problem, or because of world financial problems. All of this could contribute to the downslope.

But keeping nuclear plants going isn't ideal either--we likely will have problems with decommissioning and spent fuel pools.

I would vote for the "slow decline" scenario. I think it's probably a symmetric, bell shaped curve. It took 150 years to get to this point, and it will take another 150 years to get back to zero.

In its initial stages it will resemble the "undulating plateau" that some people talk about, but after a few years the decline will start to get steep and it will become obvious to people that world oil production is in a state of terminal decline. It will be a bad experience for people who didn't anticipate it and plan for it, but most people will survive it. Most but not all.

You think it's going to be a symetrical ride down? You don't think as oil price rises to a threshold beyond what the economy can handle, more major steps downward in the economy will lead to greater degradation of the infrastructure this civilization operates from and lead to collapse? You think complex systems that took many decades to build up can uniformly simplify to support most people? Wow, you must be a very positive person.

Yeah, I think people will manage to cope with change, albeit with a lot of complaining. And, I know of a lot of alternative solutions to conventional oil that will become popular when people can't afford conventional oil.

What you say is true — and will happen after a significant simplification of our society. The transition is going to be wrenching and we still have the little problem of most people not having the slightest idea of how to create a reasonably self-sufficient and resilient household.

In a severe contraction like what I foresee all the stock brokers and accountants and software programmers and dog walkers and college professors are going to lose their capacity to earn hard currency. The economy simply will have no use for them. Then what?

Yeah, Andre, the list is long. I have a hard time getting folks to look at this aspect of decline. Perhaps they're afraid they'll be on the list. Once the feedback from the loss of discretionary and non-essential occupations has its first effects, it spirals around to more essential jobs and services which a huge chunk of previously employed folks can't afford.

Potato chip salesmen and florists spend money too, at least until the velocity of money drops to a crawl. We've already seen round one around here, it seems. A lady I know, a type A realtor, million dollar club and all that, made my sandwich at the supermarket deli the other day. At least she's willing to do anything to pay the bills. Some people will always find something to do. Most folks?

A big part of the problem is the fact that the population grew rapidly, during the first 150 years, because of the additional food supply.

On the way down, you have to deal with declining food supply, unless (like Hubbert) you can come up with some other way of generating the energy (including fuel for actual farm vehicles). Prices are likely to soar early on. By the time we are half way down, or two-thirds of the way down, there are likely to be riots for lack of food (or maybe they have started already in North Africa). There may also be fresh water and pollution issues.

Somehow we also need to keep roads paved, and pipelines in good repair. This will become increasingly difficult, with smaller oil supplies.

There are issues with the financial system, too, like increased defaults on loans, that are likely to destabilize the system. When the economy is growing, it is fairly easy to pay back loans with interest. This becomes much more difficult in a declining system.

I'm with Gail and there is very little, if any, difference in how we view this topic.

I think that it's a grave error to think the other side of the oil production curve will mirror the front side. After a bit of conversation with me on the topic Greer agreed to modify the curve below to make it look more like a shark-fin:

We both agreed that a collapsing society would not be able to extract the remaining oil as though it were part of a well-functioning system. Do remember that the remaining oil is all the difficult to extract stuff. To think we will get that difficult oil as our financial system crumbles and infrastructure is failing is, I believe, extremely inaccurate.

Complex systems can grow slowly and organically but because of the brittleness in the system (i.e. lack of resiliency/redundancy) they tend to fail catastrophically.

A bridge may take several months or years to build. That never changes, in other words, you never see a bridge appearing in an instant. It has one mode of construction.

However, a bridge generally has two modes of failure or perhaps just one with two minor variations. Failure can occur suddenly, like when its load surpasses even the usually generous safety margins — and then it fails catastrophically.

Or it can gradually weaken due to lack of maintenance until a particular load surpasses its now-lower capacity — then it fails catastrophically, a sort of hybrid failure mode. But the end result still tends to be catastrophic failure.

I think our systems will fail via the second mode. We are in the early stages of the system weakening. At some point there will be a proximate trigger that sets the collapse in motion and one of the early results will be a cascading worldwide stock market failure. Will it be some geopolitical event that sets off the dominoes? Probably but it really doesn't matter. The important thing is to be ready for it and not to assume the systems we count on will work even at a lower level. Besides, if a system loses just 20% of its capacity and you happen to be in that 20% it has failed enough to have stopped working for you. Do you have another method of bringing in food and water?

Readers interested in this line of thinking should watch Noah Raford's "Collapse Dynamics: Phase Transitions in Complex Social Systems." He explains what brittleness and interconnectedness mean in terms of complex systems and why they are the factors to examine in depth when making a judgement about how a system will fail.

He expands on this talk a little more with "Preparing for and adapting to radical non-linear change."

So, to the people who have not yet done the work of understanding how complex systems fail, I suggest you ponder the following slide, which I think has great merit:

Your image is great! I agree with what you are saying too.

Thanks, though I can't take credit for it.