Evidence that Oil Limits are Leading to Limits to GDP Growth

Posted by Gail the Actuary on July 19, 2012 - 4:09am

The usual assumption that economists, financial planners, and actuaries make is that future real GDP growth can be expected to be fairly similar to the average past growth rate for some historical time period. This assumption can take a number of forms–how much a portfolio can be expected to yield in a future period, or how high real (that is, net of inflation considerations) interest rates can be expected to be in the future, or what percentage of GDP the government of a country can safely borrow.

But what if this assumption is wrong, and expected growth in real GDP is really declining over time? Then pension funding estimates will prove to be too low, amounts financial planners are telling their clients that invested funds can expect to build to will be too high, and estimates of the amounts that governments of countries can safely borrow will be too high. Other statements may be off as well–such as how much it will cost to mitigate climate change, as a percentage of GDP–since these estimates too depend on GDP growth assumptions.

If we graph historical data, there is significant evidence that growth rates in real GDP are gradually decreasing. In Europe and the United States, expected GDP growth rates appear to be trending toward expected contraction, rather than growth. This could be evidence of Limits to Growth, of the type described in the 1972 book by that name, by Meadows et al.

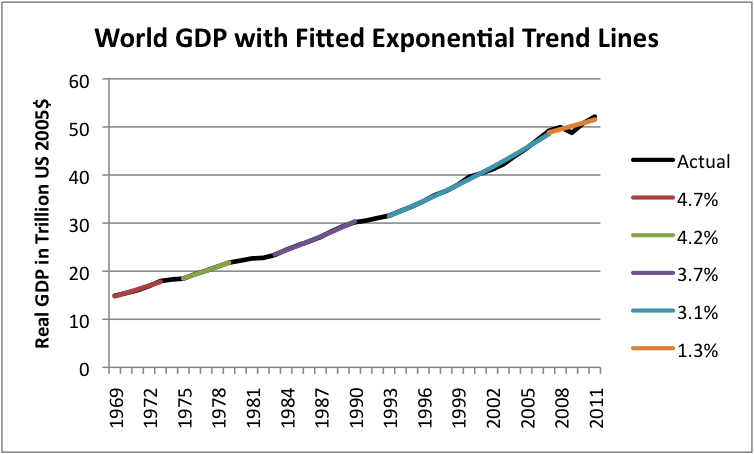

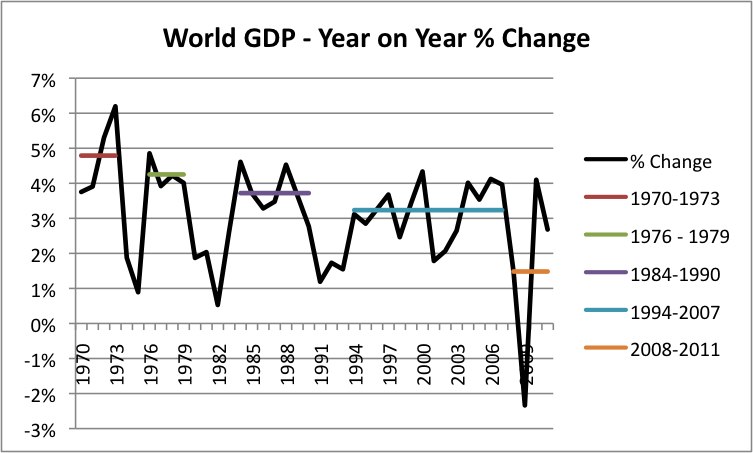

Figure 1. World Real GDP, with fitted exponential trend lines for selected time periods. World Real GDP from USDA Economic Research Service. Fitted periods are 1969-1973, 1975-1979, 1983-1990, 1993-2007, and 2007-2011.

Trend lines in Figure 1 were fitted to time periods based on oil supply growth patterns (described later in this post), because limited oil supply seems to be one critical factor in real GDP growth. It is important to note that over time, each fitted trend line shows less growth. For example, the earliest fitted period shows average growth of 4.7% per year, and the most recent fitted period shows 1.3% average growth.

In this post we will examine evidence regarding declining economic growth and discuss additional reasons why such a long-term decline in real GDP might be expected.

Connection of GDP Growth with Oil Supply Growth

It should not be surprising to find that there is a close tie between GDP growth and oil supply growth. Oil is used in many ways, from the manufacture of goods (synthetic cloth, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, asphalt for roads), to transport of goods and people, to food production (plowing, harvesting, weed killers, diesel irrigation), to operating construction equipment, to mining. While it is possible to substitute away from oil in some situations, or to find more efficient ways of using the oil, we have literally trillions of dollars of machinery in the world that uses oil right now. Because of this, the rate of substitution away from oil is necessarily very slow.

James Hamilton has shown that in the United States, 10 out of 11 post-World War II recessions were associated with oil price spikes. He has also published a paper specifically linking the recession of 2007-2008 with stagnating world oil production and the resulting spike in oil prices. I wrote an academic paper, Oil Supply Limits and the Continuing Financial Crisis, explaining some of the connections I see involved.

One connection between oil supply and the economy is the fact that when oil prices rise, indicating short supply, salaries don’t rise at the same time. Fuel for commuting and food (which is grown and transported using oil) are necessities, and their prices tend to rise as oil prices rise. Consumers cut back on buying discretionary goods and services, so as to have enough money for these necessities. This leads to people being laid off from work in “discretionary” industries, and a whole host of other effects we associate with recession.

Figure 2, below, shows world oil supply (broadly defined, including biofuels) with trend lines fitted to periods exhibiting similar growth patterns. It is these same time periods that I fit trend lines to in Figure 1, with one small exception. I had consistent real GDP data going back only to 1969, so stopped at 1969 rather than 1965 with GDP.

Figure 2. World oil supply with exponential trend lines fitted by author. Oil consumption data from BP 2012 Statistical Review of World Energy.

What we see in Figure 2 is a pattern of falling growth rates in oil supply rates, similar to the declining pattern we saw for real GDP in Figure 1. In Figure 2, the growth in oil supply falls from 7.8% per year in the first fitted period, to 0.4% per year in the last fitted period. The “gaps” that I didn’t fit lines to were periods of falling oil consumption. A glance up at Figure 1 shows that these periods where no line was fit (that is, the places where the black “actual” data shows through on Figure 1) correspond to relatively flat GDP periods–as a person would expect, if high prices/short supply are associated with recession.

A person wouldn’t expect the two types of growth rates (oil supply and real GDP growth) to be exactly the same. The GDP growth rate would likely be higher than the oil growth rate because the oil growth rate is theoretically depressed for several reasons: continued switching from oil to cheaper fuel (often electricity); improvements in energy efficiency; and a gradual change to more of a service economy. (Services use less energy per unit of GDP than the manufacturing of goods.)

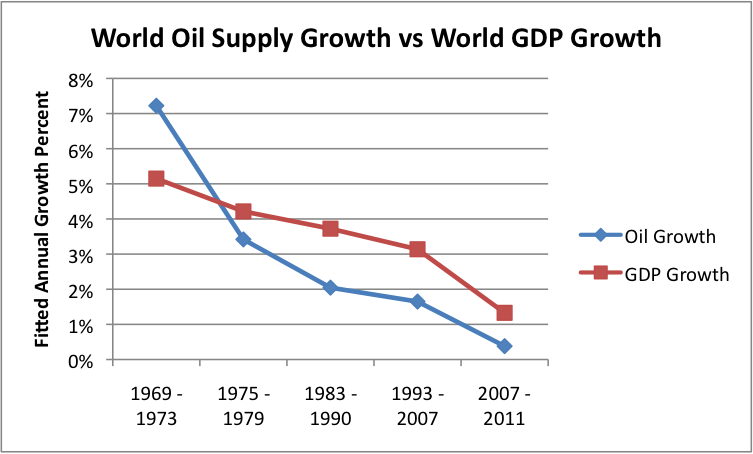

If we compare the two fitted growth rates (world oil consumption and world real GDP), this is what the comparison looks like:

Figure 3. World Oil Supply Growth vs Growth in World GDP, based on exponential trend lines fitted to values for selected groups of years. World GDP based on USDA Economic Research Service data. Earliest time-period uses 1969 to 1973 for both oil and GDP for consistency.

Downtrend in Real GDP May Be Understated

The last thing governments want to do is to let their constituents know that the economy is currently doing less well than in the past. There are (at least) two ways that governments can increase real GDP:

1. Understate their inflation estimates. The way “real GDP” is calculated involves first figuring GDP based on how much goods and services increased during the period in question, and then “backing out” the amount of the GDP increase that was due to inflation. There is latitude in figuring out how much inflation to reflect. For example, in the early years, my understanding is that if the price of beef went up, it directly affected the calculation of the inflation rate; now, there is an implicit assumption that they buyer will be willing substitute chicken to some extent instead, keeping the inflation assumption lower and the real GDP increase (as calculated) higher. There are many other things that be manipulated as well–for example, how the cost of housing goes into the calculation. The site Shadowstats gives one view of how changes since 1983 distort reported US real GDP amounts.

2. Encourage lots of additional debt. Real GDP looks at the amount of goods and services are produced and sold, not how they are paid for. If the government sponsors a program to provide mortgages to people who have no chance of ever paying them back, and this results in the sale of more houses, this will help real GDP–at least until the borrowers start defaulting on their loans. Increases in other types of loans work to increase real GDP too, including auto loans, student loans, and government debt.

Besides increasing real GDP, increasing debt also acts to increase employment, since it takes workers to build the things that people who get the loans can now afford. In other worlds, the higher loan amounts increase employment of people who build new cars or new houses, or who teach at universities.

The problem with encouraging additional debt is that it at some point the amount of debt becomes too much for holders of the debt to service, and they start cutting back on other purchases. For example, recent graduates with a lot of debt are likely not to be in the market for new homes unless they have very high-paying jobs. So, at some point, additional debt becomes self-defeating, especially when the economy is not growing very quickly. Too much debt seems to be one of the limits, besides oil limits, we are reaching now.

Other Factors Holding Down Real GDP Growth

We live in a finite world, and this fact imposes limits. The amount of land suitable for cultivation is not expanding over time. There is limited fresh water for irrigation and other uses. In many areas, water tables are dropping. Ores are declining in quality because the highest quality ore tends to be extracted first.

Pollution, including carbon dioxide pollution, leads to attempted substitution by higher cost alternatives. It also leads to the addition of devices such as expensive filters. Both of these add costs, without increasing the amount of usable goods and services (in the usual definition) produced. Peoples’ funds for discretionary goods can be expected to drop as a result, (since funding through taxes or other approaches is mandatory) putting downward pressure on real GDP growth.

There is also the issue of how many new entrants are added to the paid labor force. If, for example, in the early years, many homemakers are being added to the paid labor force, their addition will tend to raise GDP growth, because the goods or services the homemaker creates will be added to real GDP, as well as the cost of daycare for her children, if this is purchased. Once homemakers have been pretty well absorbed into the labor force, that positive influence on real GDP will disappear. If the number of people employed starts declining (because of more retirees, or because people can’t find jobs), or fails to rise as quickly, this will tend to slow economic growth.

Oil Importers are Likely to Have Lower Economic Growth than Others

There are a couple of reasons why oil importers can be expected to have lower economic growth than other countries, especially when oil prices are high. First, oil importers have the problem of needing to pay exporters for crude oil or oil products. The revenue that is spent on higher priced crude oil could have been spent on discretionary expenditures. It is unlikely that the oil exporters will reinvest the money in the economy of the buyer of its oil–they are just as likely to reinvest it in their own country.

The second reason is that oil importers tend to be the countries like the United States and Europe that “developed their economies” early on. Since these countries have hired women in large numbers since World War II, most homemakers who want jobs already have them. If birth rates have slowed, these countries may be seeing disproportionate growth in the retiree population and fewer workers in ages where employment usually takes place.

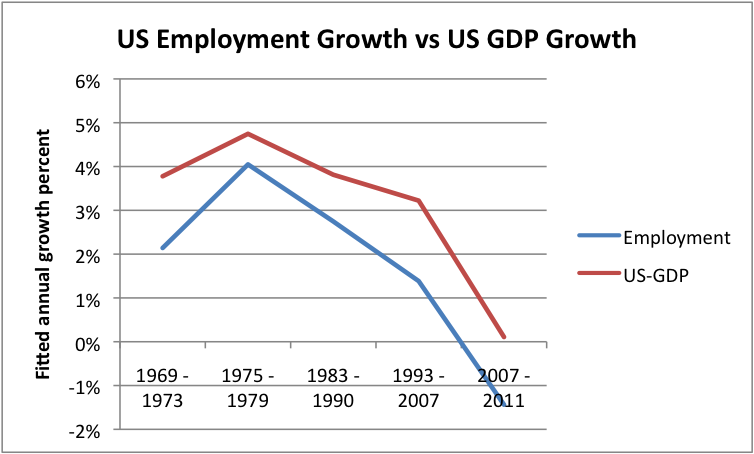

In the United States, if we do curve fitting (of the type shown in Figures 1 and 2) to the reported number of non-farm workers employed in the United States (from the Bureau of Labor Statistics), and compare these employment trend rates with the corresponding trend rate in US GDP growth, we find a high correlation:

Figure 4. US growth in number of non-farm workers versus growth in real GDP. US real GDP from US Bureau of Economic Activity; Non-Farm Employment from US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Fitted periods are 1969-1973, 1975-1979, 1983-1990, 1993-2007, and 2007-2011.

Note that decreased growth in the number of employees could be taking place for any number of reasons–less growth in illegal immigrants, fewer homemakers going back to work, more people going to college, or more people retiring or taking disability coverage, or just generally discouraged.

It is my observation that the number of workers in the US today seems to depend on the number of jobs available. If jobs in some fields are being increasingly shipped to lower-cost countries–the ones we will see in Figure 7 are now using a disproportionate share of the world’s oil–these jobs will not be available, no matter how many workers might be willing to take them, if they were available.

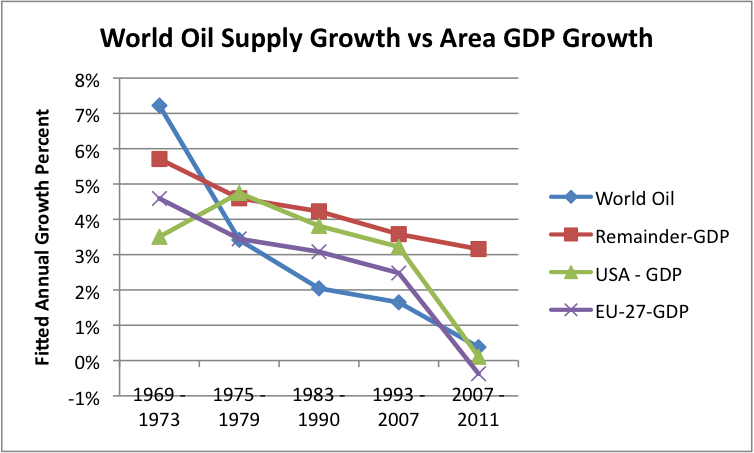

If we look at the trend in real GDP growth for three major areas (United States, European Union-27, and Remainder = World minus the US and EU-27) , we discover that indeed, all three of the areas show a downward trend in real GDP over time (Figure 4, above). The GDP growth of the EU-27 and the US start from a lower level, and drop off more in the 2007-2011 period, (when the price of oil imports was more of an issue) than the “Remainder” grouping.

Figure 5. Annual growth in world oil supply compared to annual growth in real GDP, both based on exponential trend fits to values for selected years. Oil supply data from BP oil consumption data in 2012 Statistical Review of World Energy; real GDP from USDA Economic Research Service.

One reason why the Remainder-GDP may be doing better than the others is that heavy manufacturing, and the jobs that go with heavy manufacturing, are finding their way to lower cost countries. High oil prices may also be discouraging oil importers from purchasing oil. If we look at oil consumption for the three groups, this is what we see:

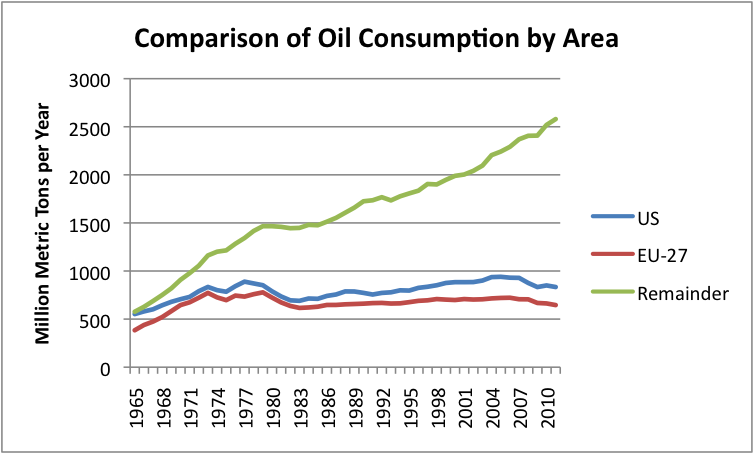

Figure 6. Comparison of oil consumption by area (United States, European Union -27, and rest of the world), based on BP’s 2012 Statistical Review of World Energy

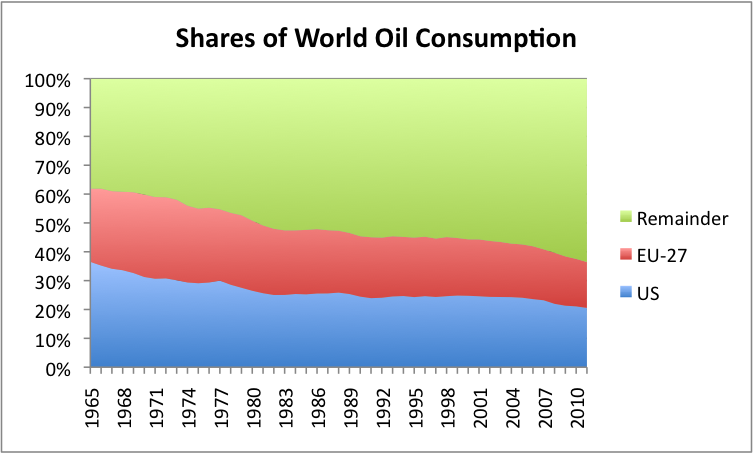

Much of heavy manufacturing has been moved out of the United States and the European Union. Figure 7 below shows that the rest of the world is now using well over half of the world’s oil:

Figure 7. Percentage shares of world oil consumption based on BP’s 2012 Statistical Review of World Energy.

Going Forward

We have seen (Figure 5, above) that all three grouping shown (United States, EU-27, and the rest of the world) are showing declining real GDP patterns, similar to the world pattern. GDP growth rates of the United States and EU-27 are both at lower levels than the World and Remainder, for reasons explained.

It is hard to see why current trends wouldn’t continue, with growth in real GDP continuing to decrease for all three groups. Regardless of the hoopla in the United States press about supposed growth in oil supply, the fact remains that growth in world oil supply has been worrisome for many for roughly 40 years, since US oil production started decreasing in 1970. It is hard to believe that the latest “fix” is going to turn things around. The typical pattern in oil supply is for extraction in an area to hit a maximum (or perhaps a plateau) and then decline.

Figure 8. Crude oil production in the US 48 states (excluding Alaska and Federal Offshore), Canada, and Europe, based on data of the US Energy Information Administration.

Figure 8 shows (among other things) how steep the US drop in oil production in the contiguous 48 states was starting in 1970. This decline set the stage for the 1973 Arab Oil Embargo, since oil-producing countries now had the upper hand. Production in Alaska and in the Gulf of Mexico eventually helped offset part of the drop, but the Alaska production (not shown) is now declining as well. Change in the balance of power regarding oil production following the decline in US production, and recognition that increased imports would cause balance of payments problems, seem to have influenced the US and Europe’s decision to focus on service industries and on industries with little oil usage, holding their oil usage down (Figure 6).

Figure 8 also shows how new onshore techniques–fracking and other enhanced oil recovery–are affecting US crude oil production. While US-48 states crude oil production has shown a 25% increase since 2006, this production is still only 39% of the 1970 amount, and about equal to 1942 production. Oil production in Canada (which includes the oil sands) is rising, but not very rapidly, from a low base. It is hard for small increases such as those of Canada and the US-48 to make up for major declines in production occurring in Europe and elsewhere. World oil supply would be increasing by more than a fraction of 1% per year if changes frequently noted in the US press were really making an important difference in world supply.

Analysis of Annual Change Percentages for Oil and Real GDP:

It is also possible to look at annual percentage changes, corresponding to the ranges analyzed above. (Some people may be more familiar with this approach.) In this approach, we "lose a year." For example, the first range is five years, 1969 to 1973. But if we use annual percentage increases, the first percentage increase occurs in 1970, and there are only four percentage changes in total, 1970 to 1973. To calculate some sort of an indication (similar to, but not equivalent, to that above), we calculate the simple average of the four increases. The resulting graphs are as follows:

Figure 9. Annual percentage increases in world real GDP with simple averages for the ranges indicated, corresponding to Figure 1.

Note that percentage changes are slightly different, but follow the same pattern as in Figure 1.

Figure 10. Annual percentage increases in world oil supply with simple averages for the ranges indicated, corresponding to Figure 2. (except 1966 to 1969 us omitted to correspond to GDP ratios and amounts shown on Figure 3.)

Here again, we note a very similar pattern. Thus, the analysis on this basis seems to be similar to that using the fitted exponential trend lines.

Tentative Indications for the Future

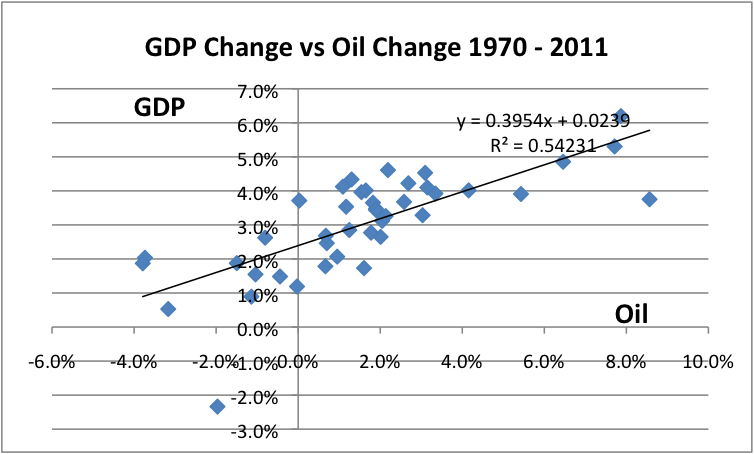

We can use the relationships between the individual year changes in oil supply and real GDP to build a simple model showing how much of an increase in GDP can be expected to take place for a given increase in oil supply.

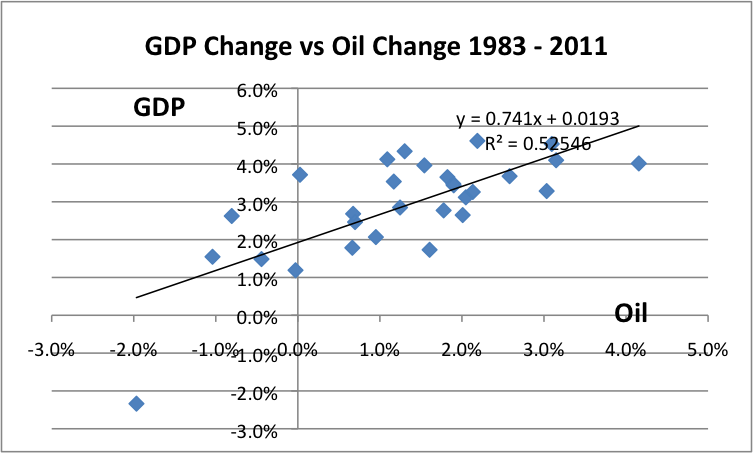

If we graph the annual percentage changes in real GDP versus the annual percent changes, what we see is the following:

It is clear in looking at the data that the pattern in the earliest part of the period is different from that in the later periods. In the very earliest period (1970 to 1973), oil use increased more rapidly than GDP. Once we realized we had a problem, there was a mad dash to try to reduce usage. If we look at only the period since 1983, when there was more of a sustained attempt to transfer to lower priced fuel, this is what the graph looks like.

Using only the recent data, the R2 is similar (.53 for 1983-2011 data vs. .52 for 1970 to 2011), but the slope of the line is a little steeper. While at R2 of .52 or .53 is not exceptionally high, it does explain a significant portion of the total variance, so let's look at what the indications of the trend lines are.

If the annual percent change in oil supply is 0.4% (as it seems to be now), the predicted annual increase in world real GDP is 2.5% per year using the 1970-2011 fit, or 2.2% using the 1983-2011 fit. Thus, both fits suggest that with the small increases we are seeing in oil supply currently (about 0.4% per year), we are already at a point where world real GDP can be expected to be much lower than most economists would prefer (2.2% or 2.5% per year).

The Figure 12 fit (using 1983 to 2011 data) would seem to be slightly better for predictive purposes, since it is more representative of the current situation.

If we want world real GDP to grow by 4.0% per year, the fit from Figure 12 (based on the equation y = 0.741 x + 0.0193) would suggest that world oil supply needs to rise by 2.8% per year. If we want world real GDP to grow by 3.0% per year, we need oil supply to grow by 1.4% per year.

We can also look at what theoretically would happen if world oil supply starts declining (but here we are on shakier ground, because of many follow-on effects). If oil supply declines by 1.0% per year, the regression line in Figure 12 would suggest that world real GDP can be expected still be expected to increase, but by only 1.2% per year. If world oil supply declines by 2.0% per year, the model would suggest world GDP can be expected to increase by only 0.4% per year. If world oil supply declines by 4.0% per year, the model would suggest that world real GDP can be expected to decline by 1.0% per year.

These are very tentative amounts. Clearly, if world oil supply or world real GDP starts decreasing, there will be many follow on effects, including political changes, and these may have effects of their own. Also, if it is clear that we again have a serious oil problem, there will be a mad dash to eliminate unnecessary use, and this may have a favorable impact on real world GDP.

But it is clear from these calculated amounts that we are entering a very challenging period.

This post combines two Our Finite World posts: Evidence that Oil LImits are Leading to Declining Economic Growth and How Much Oil Growth do We Need to Support World GDP Growth?

Thanks, Gail, for another information-rich and well-reasoned post. This is autonomous research at its best. Much appreciated.

Well reasoned? I think not. Try this paragraph from the article:

These "lower-cost countries" are supposedly using a disproportionate share of the world's oil. From eyeballing Figure 7, we find that the US had 21% of global oil consumpton in 2011, the EU 16% and the Rest of the World 63%.

From the CIA Factbook, we find that the US had a population of 313,847,465 in 2011, the EU population was 503,824,373 and the Rest of the World had 6,204,017,509, for a Total World Population of 7,012,689,347. In percentage terms, the US had 4.47% of the world's population, the EU had 7.18% and the Rest of the World had 88.36%.

Combining these figures, we can calculate that in 2011 the United States consumed 6.59 times the amount of oil per capita as the "Rest of the World" category. Whose use is "disproportionate" then?

Gail's post is an example of the sort of sloppy, complacent thinking that leads to support for US imperial wars. It is exactly the same as the thinking that has the prime problem of US foreign policy being to deal with the fact that so much of "our" oil is underneath "their" sand.

The rest of the world gets by with a good deal less oil than the United States does. Perhaps, instead of spreading gloom & doom over declining oil production, Gail could study how other countries manage.

Ablokeimet you are way off base here. Gail was not talking about the "per capita" use of oil, she was talking about the total use of oil. One can clearly see that the as jobs are being shipped to the "Rest of the World", they are also getting a larger and larger share of what oil is left in the world.

In 1965 the "Rest of the World" consumed about 38 percent of the world's oil and then now consume over 60 percent.

That was obviously Gail's point and she was spot on while you are out to lunch. Your post is an example of sloppy reasoning in order to complain about something you do not understand.

Ron P.

Maybe the US should let the rest of the world consume the remainder of global URR.

Just kidding, I like your protection and BAU as much as anyone.

No, I'm not off base. I'm just very angry. You say yourself:

To consider anyone to consume a disproportionate share of the world's oil is to have an assumption (possibly unconscious) about what a "fair" proportion of the world's oil would be in the circumstances. What would be a fair proportion of oil for 88.36% of the world's population to consume? What would be a fair proportion of oil for 4.47% of the world's population to consume? If the current shares are disproportionate, what would be proportionate? I come back to this point because, like it or not, there is no other construction that can be properly placed on Gail's statement than that she believes 88.36% of the world's people are taking more than their fair share of the world's oil production and that somewhat more should be allocated to the US and Europe. As should be obvious, the degree to which the "Rest of the World" would take offence to this is pretty strong.

Now, I don't think Gail was actually meaning what she wrote - as I said, it is the result of sloppy thinking. It also has corollaries with which she is unlikely to agree. This sort of thinking is dangerous, though. There are plenty of people who would actually agree with those words as Gail wrote them - and this in a world where wars are fought for oil.

as jobs are being shipped to the "Rest of the World"

As we saw below, that's not the primary problem.

Thanks for a fantastic article Gail. I find it astonishing that most people, even most economists, cannot make the connection between energy and the economy. Charles Hall points this out in his book "Energy and the Wealth of Nations" which I have not read because of its $80 price tag. But he does summarize it in a great video: EROEI and the Collapse of Empires

Also, as you point out in this article, the oil supply is not evenly distributed over the world. For decades, we in the west, got the lions share of all the oil produced. Now the tables have been turned. Though oil production has been relatively flat since 2005, oil consumption in OECD countries has dropped 15 percent or 2.5 percent per year since 2006.

The oil supply to all importing nations is dropping. The oil supply to the developed world is dropping even faster. And the EROEI of all the energy available to the world is dropping like a rock. As Charles Hall points out in the video I link to, most economists of the world have not made the connection between energy and the state of the economy. Energy is not even part of their equations.

Why this blind spot by the world's economists?

Ron P.

I think part of the problem is the high degree of specialization of researchers, and their lack of knowledge of other fields. Each field builds on what previous people in the same field have said. The object of the game is publishing papers that are in line with what others have said, not truly advancing knowledge.

Another issue is that politicians and businesses have a very strong interest in upholding the status quo, because growth is what gets politicians elected and helps businesses pay back debt with interest. Even if someone trips across ideas such as those I have shown, they are not likely to see the light of day given the political situations. University researchers are drawn into what governments and businesses are advancing, because that is where all of the "grant money" is. If money is being handed out for research on Carbon Capture and Storage, you can bet that a lot of university professors will work on this, regardless of how ridiculous the whole concept is.

A third issue is that we as individuals all need the possibility of "happy endings". This makes the discussion of "collapse scenarios" such as discussed in the 1972 book Limits to Growth, very difficult for most people to even comprehend.

I suppose the fact that 'Limits to Growth' failed in all it's extrapolations doesn't count for anything.

Just rub the dates off, plonk in some new ones and still claim it is all 'inevitable', and the methodology is not in any way dodgy.

It is unclear which group is the one not facing up to reality.

Could you elaborate?

"I suppose the fact that 'Limits to Growth' failed in all it's extrapolations doesn't count for anything."

Gosh, Dave, I'm just wondering if you realize that your repeated lack of citations and insistence on using absolutes where none exist pretty much invalidates your credibility as a poster. Perhaps you need to work at this more, or at least adhere to the TOD Reader Guidelines.

Regarding your claim that Limits to Growth "failed in all it's extrapolations":

You say: "It is unclear which group is the one not facing up to reality."

It's quite clear to me. Sorry for your confusion.

Apparently it is quite easy to conclude that LTG was filled with errors: simply avoid reading it and decide based on your favorite pundits.

The Limits to Growth scenarios were designed not to prove that there were limits to growth. Instead, they were designed to show the behavior of a system that contained limits (overshoot). The limits were assumed by the model.

I would agree that the LTG model was useful - it showed what overshoot looked like, and showed that overshoot was possible in a model of limited resources.

It did not demonstrate that it was a model of the real world. The model was extremely simple. For instance, resources were unitary: they weren't broken down into minerals, energy, food, or anything like that: just "resources". There wasn't an explicit recognition of renewable energy - wind, solar, etc. That's a mighty simple model.

This simplicity, and the exclusion of substitution of non-limited resources for limited resource made the model very, very far from anything that might be expected to model the real world. As the authors said repeatedly, these were scenarios, not forecasts. It was treated as such by the economics community, much to the puzzlement of environmentalists who didn't understand just how limited the model was.

Was this the main point of the Limits of Growth?

I always feel that I must have read a different book than everyone else many years ago when I first read the Limits of Growth. Every comment I have ever read about it focuses on the charts and quantitative predictions. The main take away I got from the book back then was that there was a fundamental mismatch between biosystems and political sociology: democracies generally act only when there is a crisis, but by the time we get this crisis it will be too late because natural systems will be far into a chain reaction that cannot be stopped at that point. The book predicted the key reason Global Warming will wipe us out. Homo Sapiens is a fundamentally unscientific animal and therefore must produce short sighted societies.

Did anyone else get this point? I thought it was the central argument of the book and is being proven out today. I only glanced at the graphs. I think the big mistake the book made was giving a specific set of predictions or range. When some of these predictions failed people ignored the main premise of the inevitibility of ecological disaster given our limited psychological and sociological abilities- and this premise is true.

Every comment I have ever read about it focuses on the charts and quantitative predictions.

uhhmmm....mine didn't.

Yes, the model was intended to show overshoot, and one could plausibly argue that applies to Climate Change.

I'd quibble that the model didn't really anticipate Climate Change - the pollution it modeled didn't have the very long development time/lag time of Climate Change. In a sense, they "got lucky" - something happened that resembled the behavior of their model.

Worse, Dennis Meadows is out there arguing that peak Fossil Fuels will cause TEOTWAWKI.

That's ironic, given that Peak FF is far less damaging than Climate Change, and would possibly prevent Climate Change if only FF were as limited as Dennis thinks.

The major problem is that the framing is bad: Climate Change isn't primarily a growth-related problem, it's a pollution problem - it could have happened with lower growth rates, and it could have been prevented without eliminating growth.

LTG has been criticized for not anticipating a variety of things, such as increasing efficiency on the positive side and climate change on the negative side. But this, in my opinion is exactly why the very general categories used in LTG stand the test of time. Climate change falls into their general category of environmental degradation and will certainly be a serious drag (if not a total death-knell) on human civilization. It was not necessary to anticipate exactly the nature of the specific trends that developed.

And BTW there was at least one scenario they ran in the original study that had a positive outcome, or at least a steady-state outcome and not a collapse.

The model only went to 2100, so lasting to 2100 isn't really permanent, IMO. We are still dealing with a finite world.

One major thing that LTG left out is the financial system, and what its needs are. To me, the financial system is the part that gets stressed first. Leaving it out makes the model suggest that bad outcomes will play out more slowly than in real life.

Needless to say, political systems are also left out. This adds yet another dimension that can amplify bad outcomes.

We are still dealing with a finite world.

As a practical matter, in the longterm we don't face limits on available energy.

OECD energy consumption will never need to grow much above where it is now, and the rest of the world will plateau in a few decades in the same way. That plateau is far, far below the 100,000TW of solar insolation.

LTG did not fail in all its extrapolations. The authors actually mention that they are not predicting future events precisely:

"we cannot predict the population of the US, the GDP of brazil or the world production of food in the year 2015. the data we are working with are not sufficient for such predictions" (a rough translation from the German edition, so perhaps not quite what is in the English edition)

The Wikipedia page on LTG has this to say: "The purpose of The Limits to Growth was not to make specific predictions, but to explore how exponential growth interacts with finite resources. Because the size of resources is not known, only the general behavior can be explored." (emphasis mine)

If you want to look at a recent comparison of what was predicted with what is happening, then check this link: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/Looking-Back-on-the-Limits-... - but be warned, it may upset your world view..

Thanks a million for this link Fierz. I had no idea LTG was so spot on so far. I am going to save this link and post it the next time someone starts trashing Limits To Growth.

Ron P.

This is a comparison of 1972 projections with one author's depiction of the actual experience. This does not show that TEOTWAWKI is happening or will happen, just that BAU growth curves are still continuing. This is only bad news if limits are indeed awaiting the economy around 2015, as suggested by some of the (many) LTG scenarios.

Please note that the author's curves are questionable. In particular, the "resources" curve is highly unrealistic, given the existence of resources which are much, much larger than human consumption (especially solar energy: 100,000TW of resource vs 10-20TW actual consumption).

Nick, if it's not business as usual then it is the end of the world as we know it later in the century. Every curve on the chart goes down. This could only be caused by TEOTWAWKI. Business as usual has everything going up... forever.

The authors curve of non-renewable resources remaining is very realistic. Solar is not counted as non-renewable unless you are talking the sun dying out. And your figure of Terawatts of solar power is unrealistic. That and a lot more may fall upon the earth but it's what you can realistically and economically turn into electricity or horsepower that counts?

Ron P.

Every curve on the chart goes down.

Yes, but that's still in the future, and is yet to be tested.

Solar is not counted as non-renewable

Well, that would be my choice, yet the LTG model includes all energy (excluding agriculture) in the non-renewable category. That's part of why the LTG model is so unrealistic.

your figure of Terawatts of solar power is unrealistic

That's the resource. Sure, we might only be able to capture 1% of that - that's still 1,000TW.

it's what you can realistically and economically turn into electricity or horsepower that counts

Wind and solar are scalable, affordable, high E-ROI, etc.

Wind is cheaper than new coal.

Solar has reached grid parity in many places, and even if it's a bit more expensive than coal and NG in most places, it's still very affordable.

That did it. The very idea that we might be able to capture 1 percent of the sunlight that falls upon the earth it totally and completely absurd. The area of the earth is 198 million square miles. Sunlight falls upon half of that all the time. That would mean one million square miles of solar panels.

But wait, solar panels are only 11 to 15 percent efficient. Let's give you the benefit of the doubt and say 20 percent efficient. That would mean 5 million square miles of solar panels to get the equivalent of 1 percent of the solar power that falls on the earth.

Oh well, what could I have expected? Of course a fraction of one percent would be enough. Lets say a million square miles, or only 100,000 square miles, 1/50th of one percent. Think that is possible?

Let us not get ridiculous. Throwing such absurdly large numbers around without any reasonable way to turn them into reality adds nothing to the debate. It only serves to muddy the waters.

Ron P.

The very idea that we might be able to capture 1 percent of the sunlight that falls upon the earth it totally and completely absurd.

Exactly my point: there's far too much sunshine for us to ever need or want to use up a significant fraction.

No that was not your point. Your point was that there was so much sunshine we could easily capture it and use it for power to replace oil. Contrary to what you state above, we would desperately want and need to capture sunshine and use it. But there is no way we could build enough solar panels and batteries to store the electricity when the sun don't shine and build enough electric cars and charging stations to make a dent in liquid fuel use for transportation.

Your entire point was that solar power is so abundant that it could easily replace oil. You are sorely mistaken on that point.

Ron P.

Your point was that there was so much sunshine we could easily capture it and use it for power to replace oil.

My point is that as a practical matter we won't run out of sunshine. And, that's the case.

there is no way we could build enough solar panels and batteries to store the electricity when the sun don't shine and build enough electric cars and charging stations to make a dent in liquid fuel use for transportation.

Now that's a different question. And, of course we could.

Let's break this down:

solar panels

Wind is a cheaper way to indirectly capture solar energy at the moment, so for the moment we'll maximize that - $2k of wind turbines will power a car for life.

Panels have become very affordable - Germans are installing them for $2/Wp. The average European car only drives about 13k km per year - at 5 km per kWh, that's only 2,600 kWh per year, which would require perhaps 3KW of solar panels. That's only $6k, to power the car for life. That's still much cheaper than oil.

batteries to store the electricity when the sun don't shine

For light vehicles, the battery is part of the car. That's pretty straightforward.

build enough electric cars

They're pretty much as easy to build as ICE cars.

charging stations

PHEVs and ERVS will dominate for a long time - they can displace 90% of liquid fuel, and ethanol can handle the other 10%. For EVs, most people would charge at home. charging stations aren't a big deal - they exist now in Canada (and a little in the northern US) for engine block warming.

Run out? No, but that doesn't change the fact it is diffuse and intermittent.

Europe is a special case with very high gas taxes and very high subsidies. And you seem to have forgotten the higher costs of EVs negate these savings.

So are battery costs, which you neglected. And Darwinian wasn't talking just about light vehicles, but industrial society as a whole.

Except for the batteries.

PHEVS and ERVS dominate nothing, they are a rounding error in the grand scheme of vehicle sales. And you are neglecting the fact the world's grid's can't handle the additional load. You are also neglecting the load shifting infrastructure to charge these EVs at night.

Nick, your writing is as compelling as a six grade science fair exhibit. I don't know why you keep at it. Its not like this hasn't been pointed out to you before.

Rethin,

it is diffuse

It's common to say that renewable power sources are "diffuse". Is that realistic?

No. Let's discuss the land needed for wind power:

Right now 60 acres per turbine is pretty standard (probably 1.6MW), for 37.5 acres/MW.

Farmers have often gotten about $4K per 1.6MW turbine, which meant about $40K on a 640 acre farm. 10 turbines means they only lose 5 acres of productive farmland (less than 1%), and perhaps double their net income. That's huge money for a farmer.

Conventional comparisons:

There are 525,000 operating oil wells in the US, and probably 10M abandoned or dry wells. There are 70,000 abandoned coal mines - shouldn't we include those somehow in space requirement calculations?

Regarding the land use footprint of a nuclear power station, let's fire up Google Maps and take a peek at Sizewell on the UK Suffolk coast. The site contains the now-decommissioned Sizewell A, and an American style PWR, Sizewell B, about 1.2GWe (1200MWe), which has been running happily at about 90% load factor since 1995. The scale rulers on the map indicate that the site is pretty close to 1 sq km (100 hectares). Similarly, we can cruise over to Finland, and look at the Olkiluoto site, where reactor 3, also about 1200MWe is under construction. The area per GWe is very similar to that of Sizewell. So that's ONE (1) sq.km per performing GWe, close enough.

To this we of course have to add the land use for mining and refining the uranium yellowcake.

Wind power consumes very little land - perhaps 1/2 acre per 1.6-3MW wind turbine - much less than other forms of generation, when you include fuel mining and the overall footprint of generating plants (nuclear plants can take up more than a square mile). Rooftop solar doesn't consume any land.

The Clinton Power Station is located near Clinton, Illinois, USA. The nuclear power station has a General Electric boiling water reactor on a 14,300 acres (57.9 km2) site with an adjacent 5,000 acres (20.2 km2) cooling reservoir, Clinton Lake. Due to inflation and cost overruns, Clinton's final construction cost exceeded $2.6 billion, leading the plant to produce some of the most expensive power in the Midwest. The power station began service on April 24, 1987 and is currently capable of generating 1,043 MW.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clinton_Nuclear_Generating_Station

a wind turbine may only stand on 1/2 acre, but you can't pack them that dense, and no one wants to get perticularly close to a working wind farm either. So the land use is larger than that figure implies.

The land between wind turbines isn't "consumed" - it can be used for other things. This is clearest for farmland - the land in between can be planted quite nicely. Farmers love wind power (it brings in a lot more money than food crops), and in the US there is an enormous wind resource in farm areas. A nuclear plant, OTOH, encloses it's land for security reasons, so it's really unavailable for other uses.

The Clinton nuclear plant uses 20 acres per average MW, and a 3MW wind turbine on a 1/2 acre uses 1/2 acre per average MW. Coal and nuclear also have to add in the space used for mining - there are 70,000 existing and old coal mines in the US.

intermittent

Are we talking daily (diurnal) variation, or seasonal? Each of those is a different (long) discussion.

Europe is a special case with very high gas taxes and very high subsidies. And you seem to have forgotten the higher costs of EVs negate these savings.

Yes, Germany is farther north, and Europeans drive less, so it's a more conservative case. The economic case for solar is much stronger in places like the US, where insolation is much stronger and the vehicle miles are much higher.

battery costs, which you neglected.

No, those are included in the cost of the vehicle. Over their full lifecycle EVs are cheaper than ICEs, even with artificially low market prices for fuel, as we have in the US.

Darwinian wasn't talking just about light vehicles, but industrial society as a whole.

True. OTOH, the majority of liquid fuel consumption is by vehicles, and the great majority of that is light vehicles. Industry can move from liquid fuels pretty easily, as they primarily use electricity.

the world's grid's can't handle the additional load.

The world's utilities are eagerly awaiting EVs, as they will add load at night, when the grid is underutilized, and help deal with renewable intermittency.

the load shifting infrastructure to charge these EVs at night.

Smart meters, which are being installed as we speak, and which pay for themselves by reducing the labor needed to read meters.

six grade science fair exhibit.

I notice that your comments still have sarcasm and personal attacks. Too bad. Is it an attempt to intimidate and silence people who disagree with you, or are you just angry because you think I'm somehow doing harm? I find it puzzling - I think we're really on the same side, which is moving the world away from oil and fossil fuels.

The Clinton Power Station is located near Clinton, Illinois, USA. The nuclear power station has a General Electric boiling water reactor on a 14,300 acres (57.9 km2) site with an adjacent 5,000 acres (20.2 km2) cooling reservoir, Clinton Lake.

Oh, I have a competitor for the Nuke plant that uses the most land! Dominion Power dammed a stream in the middle of my state to build a lake 53 km^2 dedicated to cooling the plant. The plant itself is another 4.35 acres, for a total of 57.35 km^2, *just* shy of Clinton. But surely North Anna still holds the record for length, at 27 km (17 mile)?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lake_Anna

That's a big lake!

Nick, one of the main reasons we have a liquid fuels problem now with high prices is peoples choice. In the US despite these high prices the number one selling car is the Ford F series pick-up truck. There is no hope of replacing cars like the Raptor, powered by a 411 hp 6.2 L V8, with an EV that uses...

The type of EV that replaces SUVs will need to be big and heavy, to be bought by those wanting big and heavy cars. Such a beast does not exist.

We can use a lot less liquid fuel now if everyone chose a small efficient diesel or petrol 4 cyl.

You a very good at describing a utopian world where we can do lots of things, pity we exist in the real world where we are heading straight for the energy (and economic) cliff because of overshoot and failure to plan.

Hide_away

You a very good at describing a utopian world where we can do lots of things, pity we exist in the real world where we are heading straight for the energy (and economic) cliff because of overshoot and failure to plan.

So are you saying that with very high gasoline prices ( $4/gallon is not really very high) people will prefer to loose their jobs and keep Ford F pickups, rather than car pool or commute in very fuel efficient ICE vehicles, EVs and EREVS. ??

Nick is not describing a utopian world, its a world very similar to what we have now same traffic jams, people living and working much as they are now, just using a lot less oil and an relatively small increase in electricity consumption distributed on a national grid very similar to what we have now. This is only possible because most ICE vehicles are very inefficient in using the energy content of petroleum products but electric motors are very efficient in using the chemical energy stored in batteries.

We are fortunate that cars have a relatively short lifespan, so once we start seeing real expensive gasoline(ie higher than EU prices) the shift to better fuel efficiency, car pooling and EVs will result in big reductions in oil consumption.

Isn't that exactly what's happening right how? High gas prices, people are losing their jobs and ev/erev sales are almost nonexistent.

Gas prices are very low in the US. For most people, depreciation is a much larger expense than fuel.

Hybrids, like the Prius, are also electric vehicles, and they're doing fairly well.

Yes, EVs are taking off slowly. The (faux) media are attacking them viciously, and fuel prices are artificially low ($2T oil wars, anyone?).

Still, they're available: anyone who wants to can become independent of oil for personal transportation, overnight, and reduce their overall cost of living.

That is the reality of the situation NOW!!

Nick keeps telling us that EVs are cheaper now, yet the populace is still buying SUVs. There is a disconnect between what some people say/think is possible and what is clearly happening.

Nick keeps telling us that EVs are cheaper now, yet the populace is still buying SUVs.

They're only slightly cheaper (given current artificially low fuel prices), and even realizing that is true requires a long-term view point, one that the media don't promote.

one of the main reasons we have a liquid fuels problem now with high prices is peoples choice.

True. The media are telling people that high prices are temporary, and that EVs are bad. It's understandable that people would make the choices they do, but it's a shame.

the number one selling car is the Ford F series pick-up truck

The Prius is the number one seller in Japan, and it's doing pretty well in the US.

The type of EV that replaces SUVs will need to be big and heavy, to be bought by those wanting big and heavy cars. Such a beast does not exist.

Here's an OEM Ford Ranger EV Pickup, and a EREV light truck (F-150).

Here are electric UPS trucks. Here is a hybrid bus. Here is an electric bus. An electric dump truck. Electric trucks have much less maintenance.

Kenworth Truck Company, a division of PACCAR, already offers a T270 Class 6 hybrid-electric truck. Kenworth has introduced a new Kenworth T370 Class 7 diesel-electric hybrid tractor for local haul applications, including beverage, general freight, and grocery distribution. Daimler Trucks and Walmart developed a Class 8 tractor-trailer which reduces fuel consumption about 6%.

Volvo is moving toward hybrid heavy vehicles, including garbage trucks and buses. Here is the heaviest-duty EV so far. Here's a recent order for hybrid trucks, and here's expanding production of an eight ton electric delivery truck, with many customers. Here are electric local delivery vehicles, and short range heavy trucks. Here are electric UPS trucks, and EREV UPS trucks. Here's a good general article and discussion of heavy-duty electric vehicles.

Here's an electric mobile strip mining machine, the largest tracked vehicle in the world at 13,500 tons.

In all those links you provided, there is not one SUV equivalent that can be purchased off the rack from the local dealer.

As I stated, such a beast does not exist, especially getting 5km/kwh, as you stated was possible.

The simple point that the F-series pick up truck is the number one seller in the US, seems to have been missed. That is what people are choosing.

A few thoughts:

How do you feel about the Prius V?

I never said that an SUV equivalent would get 5km/kWh. That figure is an average. Small cars can get twice that, while SUV equivalents might get 3km/kWh.

The F-series is just one model out of many. The fact that it's at the top doesn't tell us quite as much as it might seem, given the fragmentation of the market.

On the other hand, you're absolutely right - things are still early for hybrids/evs, etc. They started at the low end of the market and are moving up. How quickly that happens depends on a wide range of social choices, including artificially low fuel prices.

Nick,

The most important point is that EVs and EREV are actually being manufactured now. In 2005 the Hirsh report virtually dismissed EVs as a solution to the coming oil shortage. In the 2008 oil price spike they were on the drawing boards, but few considered EVs an option. Now production is ramping up quickly from a small base so we should start to see unit costs declining. Does anyone doubt that the US could rapidly re-tool all auto-production capacity to EVs, hydrids and EREVs if faced with an real oil shortage requiring WWII type rationing.?

The opposition to EVs is understandable, on the one hand a lot of auto dealers/mechanics and oil refining and retailing outlets will become obsolete. On the other hand those who are attached to the idea of purely mass transit or bicycle transport, redesigning livable cities etc will be disappointed that the end of oil will not kill off the private automobile. It may not even kill of the SUV and that's a pity.

Good thoughts.

One quibble - I think battery production might be a bottleneck, which might limit the number of pure EVs, and require some interim carpooling as we ramp things up. Carpooling even now carries more people than mass transit in the US.

Carpooling - the horror.

This is a comparison of 1972 projections with one author's depiction of the actual experience. This does not show that TEOTWAWKI is happening or will happen, just that BAU growth curves are still continuing. This is only bad news if limits are indeed awaiting the economy around 2015, as suggested by some of the (many) LTG scenarios.

Reading this made me wonder whether or not the ZIRP (zero interest rate policy) of first Japan, then the USA and Europe is a consequence of falling GDP growth in some way, and not originally a politically motivated stimulus.

It also reminded me of this post on a favorite blog of mine:

http://pipeline.corante.com/archives/2012/07/20/does_anyone_want_to_inve...

It outlines how tech companies like Google are sitting on a mountain of cash with which they cannot find anything useful to invest in.

And this brought me back around to thinking about all the failing infrastructure in the western world that no-one can afford to replace. It seems like we are already living in a world that is a left over legacy of a previous era of expansion. Even though people need bridges, water mains and power grids we cannot afford to pay for them in a way that makes a profit for investors (who would rather sit on their billions and watch them inflate away slowly).

This observation makes me gravely suspicious of being able to invest in alternative energy technologies as a society. My feeling is we will be lucky to get a couple of decades of bicycle use of the current road system before it too crumbles.

I agree that the zero interest rate policy is related to very low/ no growth. IF the economy is growing quickly, then it is possible to pay reasonable interest rates.

I looked at the possibility of investing our way out of an energy shortfall, and decided that there is no way it would work. Can we invest our way out of an energy shortfall?

Gail, thanks for the link, great article. At some point, the US will run out of assets to leverage.

Excellent graphs...the data speaks for itself.

Retire or not to retire? That is the question. Oh well.

Paulo

My view is that the money for retirement that is available to you today is likely not to be available to you tomorrow. Thus, the money in bank accounts is likely to either lose value or will disappear for some reason--the electrical supply to the bank is no longer working; the government puts a cap on how much that can be removed in a given week at $50; or there is some other huge change, such as substitution of local currencies for national currencies, that changes the nature of the "ball game' greatly.

Pensions have their own particular issues. They have been making investments, assuming annual returns in the 8% to 10% range. These haven't been happening. The US government guarantees these up to some extent, but at some point in time the number of government guarantees would seem to be overwhelming. If pensions have problems, there is a good change banks will have problems as well.

Social security (and most other government programs) are more of a pay as you go plan, with funding today for today's recipients. These may continue to some extent, but if the country is poorer, the relative benefits are likely to decline.

So in making the retirement decision, it seems to me that you need to consider that in the future you are likely to need to work. If there is some way you can temporarily "take a break", and spend money you have today that likely won't be there tomorrow, there might be a possibility of temporary retirement. You might also spend some time/money becoming better friends with the younger generation, because we are likely to be depending on them more in the years ahead.

I have long realised that a financial pension will not exist by the time I retire. In the UK the poor receive a flat rate state pension provided they have spent most of adulthood in taxed employment, but it is not much more than a basic safety net against extreme poverty. Middle income people are expected to pay into a stock and bond market based fund managed by fund managers who all end up extremely rich regardless of the success or failure of the funds they manage. The rich manage their own money and make sure they stay rich. Already the state pesnion is becoming a receeding horizon. Entitlement age for men has risen from 65 to 68 for my age band (under 50). By the time I am 68 that figure will be 75... The token amount I invest in my pension fund is performing badly.

I have two real pensions. My parents and their parents both had the good sense to have small families. The same for my wife. We have inherited two properties in a wealthy area (presitigious university city) and will soon inherit enough to buy a third. The rental income from these properties will be enough for a comfortable retirement that should ride the energy descent curve reasonably well provided that title to property is retained. My second pension are the two children we adopted out of poverty, abuse and neglect some years ago. Although nothing is certain I hope they will become our property managers and maintainers when alternative employment is hard to come by.

For various reasons I gave up on rental property some years ago. It has occurred to me that that might have been a mistake as all of my retirement funds, minus social security, are invested in financial markets, mostly corp. bonds and CDs. Yet now I wonder if even local rental property is safe. If no one has any money, who is going to pay rent?

There is always someone willing to pay rent. It just might be a lot less than what you're looking for.

My experience in real estate is that price is the #1 factor in whether something sells or not. Not the only factor, but the biggest one. Rents are pretty high right now (ironically, partly because many people were pushed out of their houses during the housing crash and related foreclosures), but if things go downhill eventually rents must decline or there will be a lot of empty properties.

There is another way to invest in making sure your future needs are met after retirement as I am doing. You can INVEST in reducing your

use of energy and resources in as many ways as possible. I have a folding bike which I can take on any train or bus to have Transit without oil. I bought the best triple pane insulated windows, an energy efficient new furnace, and new insulation and have cut my natural gas usage by over 50%. I will soon be installing a solar carport grid connected capable of supplying 100% of my own energy plus when the sun is shining - selling to the grid for Solar credits during the day and consuming only at night so that my electric bills will be $0. At current rates I will earn over $1500 per year on electricity I supply the grid. I live a few blocks from a train station where I walk to take the train to work and other places with my monthly pass for $100 per month versus $500 per month equivalent driving at $.50 per mile for driving. When I retire if it still exists NJ Transit offers senior discounts which are even cheaper to ride the train or bus.

I live in a 19th Century "Transit village" community of about 1200 people ready for the 21st Century reality with our own post office, library, school, public performance space, parks, grocery store, 6 restaurants all within easy walking distance. We also have a 9 hole golf course and playground public space which I find pretty but useless as I find golf boring and stupid. But it *could* grow our food in the future if needed.

I do NOT live out in some rural boonies but 1 hour train ride from New York, Hoboken, the Jersey Gold Coast, and just about any cultural, educational or entertainment event you can think of.

Some day I will also be able to take the restored Lackawanna cutoff Rail line to the "mountains" in Northwest New Jersey and Pennsylvania or to the beautiful Catskills in New York via the "Jersey Crescent" along the I 287 median.

If we truly believe that oil and all resources will become increasingly scarce in the future isn't the best investment any way in which you try to reduce your consumption of these resources to 0?

As my neighbor said who invested in solar panels on our local grocery store told me - they can tax or you can lose future income. But if you CONSERVE and never spend in the first place that can never be taxed or taken away and lost!

I don't think most people here really appreciate the dramatic growth possible (inevitable? necessary?) in solar energy and in energy storage. I leave out wind because it's a well established industry. If you put your retirement into a *diversified* set of solar, energy storage, and smart grid that provides value to energy users (not just the utilities), then you might have a pretty darn good chance at having a retirement fund. And worse case, if the money evaporates, then you might at least have some ownership interest in a physical asset that actually generates energy.

What would change if you could only conduct bank transactions (because the computers were only powered) when it was sunny or windy? You'd probably start paying attention to the daily/weekly energy forecast, and schedule around the weather instead of some artificial 9 to 5 regiment.

Those that had invested early in on-site generation, as well as long-lasting energy storage would have a serious competitive market advantage over the latecomers who will insist on seeing a 2 year payback.

The only reason to worry about your retirement is if it depends on unchanging daily cash flows. If you can deal with variability (both in market volatilty and energy availability), then you will probably do pretty darn well, and maybe we can all take days off when the wind stops, and get cheap electrified rail transport and rates to the tourist spots during their local windy season.

What would change if you could only conduct bank transactions (because the computers were only powered) when it was sunny or windy?

Realistically, that's maybe 5% of the time. If cheap underground storage of simple fuels ( such as hydrogen or ammonia) created during periods of surplus power generation and burned in cheap peaker turbines doesn't work (and it will, if needed), it won't be a hardship.

This statement is very questionable:

For the USA this is patently false at this point in time.

As has been pointed out by many TODers in this site Auto Addiction is the biggest use of US oil at about 69% of oil usage for cars, trucks and air transit. There IS a substitute

almost immediately available for this usage - namely vastly more efficient Green Transit usage of our already built trains, lightrail, buses and shuttles along with bicycles and walking. The Auto Addiction lobby myths that the US is "too vast and spread out" for Green Transit, that Americans will not use it, that it will cost too much and take years to transition are false. In fact 79% of Americans live in urbanized areas according to the FHWA whose mandate is to support highways. Brookings in May, 2011 completed a 2 year in depth study of Census data, transit and jobs which found that already 70% of working age Americans in 100 US Metro areas live only 3/4th mile from a Transit stop. Note that this is without laying a single Rail, buying another bus or buying another shuttle. Unfortunately since the 2008 financial crash Green public transit has been very hard hit with over 150 cities facing major transit service cuts and fare increases. Ironically TODers like Gail would appreciate the connection to the financial meltdown as many of these public transit agencies like the DC Metro got hit hard with their interest rate swaps still going to banksters rather than running public Transit.

Adding to the irony is that when gas prices first hit $4 per gallon in 2008 and Americans were flocking to public transit in droves was exactly when cuts were made all over the USA. I experienced that directly in my daily Rail commute - my train stop's parking lot was full as people in desperate search of parking came to my train stop which still had some available parking. This is not to mention myself and most train riders at my stop who walk to the station as about 2,000 people live within walking distance. Across the US public transit ridership was increasing by double digits. And then it was cut in town after town due to increased fuel costs, default swap callbacks and municipalities budget crunches.

If the US, which consumes 25% of the world's oil, wants to cut oil consumption it is

very simple and could take affect within months - simply RESTORE all the public transit cut since 2008 by the Federal government restoring operating subsidies which had existed for decades until Reagan.

This is not a "shovel-ready" stimulus this is a "NO shovels" stimulus!

Permanent Green Transit jobs would be created immediately calling back laid off Transit workers and college students who have had to stop school due to lack of Transit, those who can no longer afford cars and others who want to cut gas expenses would get back a public transit option.

This could easily be paid for by a $.20 increase in Federal gas taxes which is long overdue.

At one time, even Boone Pickens was in favor of increasing the gas tax, perhaps up to the same level as the EU, offset by cutting the US Payroll (Social Security + Medicare) Tax.

Old Republican Cabinet stalwart George Schulz has even endorsed a straight carbon tax as reported in another story linked from TOD!

There is hope I believe for fundamental change. The question is will it come soon enough?

Although just RUNNING existing Green Transit is easy, the next stage of actually restoring our Rail network can be a lot more expensive. For example the cost overruns on restoring the NYC 2nd Ave Subway.

As we here know it will get more and more expensive to run the

bulldozers and other oil-fueled equipment needed to restore Rail and to do new Projects like building down strategic highway medians where no Rail ever ran before.

I was speaking about over $1 trillion in world built infrastructure. We have cars, trucks, boats, electrical systems, factories, home heating and air conditioning systems, and many other things that need oil in some way--certainly for lubrication, but also for maintenance, and servicing with new spare parts. Maintenance of huge grid-connected wind turbines depends very much on the fossil fuel system, so it is another part of the world built infrastructure that is likely to fail, with oil supply problems.

Then the umpteen electrical engineers who have posted on here to the effect that the grid can be run just fine on very limited supplies of oil, well within the possibilities of biofuel must be seriously ill-informed on what it takes to run a grid.

Either that or we get into the circular pattern of reasoning that no part of the system can be maintained as the whole system of economics and everything else will crash.

So the crash is inevitable because of the crash.

The electrical grid can run just fine on limited quantities of oil because the vast majority of electrical generation uses fuels other than oil. The small amount of oil required for lubrication and fuel for maintenance vehicles is insignificant in the overall market.

The highway system is totally different. The vast majority of vehicles run on petroleum-based fuels, so in the even of a serious oil shortage, the whole thing will come to a screeching halt.

Note that I'm assuming the electrical utilities will be among the fire departments and ambulances in getting priority in any kind of rationing system.

Of course, the electrical grid is part and parcel of a larger economy utterly dependent upon fossil fuels, especially liquid fuels. Supported entirely by rate payers whose incomes are dependent upon cheap non-electrical energy in many ways, our electrical grids are equally dependent. The whole system's vulnerability to declining fossil fuel availability and/or rising costs effects all of its sub-systems and our collective ability to support them. It's our reliance upon highly complex interconnected systems that most folks have trouble understanding; our ultimate vulnerability. Overshoot encompasses everything.

I agree. You said it well.

Thanks, Gail. I hope to see more whole systems posts and discussions as I feel TOD does a great job of covering various aspects of peak oil, etc., but it tends to become compartmentalized, losing sight of the big picture. Whole systems analysis is a tough nut, as much art as science, but essential to discovering where we are and where we're going. This post is a refreshing step in the right direction. Thanks again..

Several editors at TOD object to whole systems analyses, in general, although some numerical analyses are OK. They want this to be an oil site. This is one reason I write at Our Finite World, where I have latitude on what I can write.

There is also an issue of how readers respond. Readers like "happy endings". Whole systems analyses tend not to come up with happy endings. If readers get upset, the discussion tends to go downhill badly, with many arguing that the reasoning must be wrong, awful things couldn't happen to them, etc.

Gail, I understand where the TOD editors are coming from, but one would think that by now they should be beginning to understand that the oil affects the whole system and the whole system affects oil. Everything is tied together in a complicated mess.

People focusing on oil, and only oil, is the reason some peak oilers still see oil prices going to $200 and even higher. They fail to realize the devastating effect high oil prices have on the whole economic system.

My Dad, who married in 1927 and raised a family during the depression, said things were dirt cheap during the depression because no one had any money to buy anything and that drove prices down. People who expect oil, or any commodity for that matter, to be extremely high priced while the world wallows in a depression betray their lack of understanding of the whole system.

And TOD editors who insist on concentrating only on oil while leaving whole system analysis out of any coverage only help to perpetuate this misunderstanding.

Ron P.

Ron, I couldn't agree more that: "everything is tied together in a complicated mess". Down thread I asked Gail about an estimate of where GDP would be minus all the debt spent on consumption, lack of savings due to overly generous promises to retirees as well as income generated on the spread between borrowing and investment/speculation. My back of the envelope estimate for a reduction in GDP is about 10% for debt spending, 10% for savings and 5% on the credit spread. Credit spread being roughly 2% on about 250% of GDP. In other words, an eventual reduction of GDP similar to the Great Depression but since the system is far more out of balance than it was at the end of the 1920s, the likelihood of a near term overshoot of the 25% is a real possibility.

So, the idea that in the near term there will be a surplus of commodities, at current prices, would indicate that peak oil for the next few years/decade will more than likely be a monetary event rather than a physical supply event. How that plays out in individual countries will be determined by a whole host of monetary, political, military, balance of payments and maybe the most important of all: food production issues.

The trap that many countries will have IMO, as many have discussed in TOD, is that there will not be sufficient wealth remaining to make the investments to a lower energy intensive economy. The ironic thing about that is that, as Russia shows, it may be some of the resource rich developing countries that bear the brunt of the economic decline.

Great post NC, and I agree with everything you say except this:

I am going out on a limb and calling peak right now. The decline will start, or started in June 2012. So it will be a physical supply event in my opinion. I expect prices to go higher later this year then turn down as the world slides into a deeper recession in 2013.

Of course everything is just a guess but I call it an "educated" guess. I follow the production numbers of every producing nation very closely. And I also look at what they have coming on line in the next few years. I see depletion overtaking new production in late 2012 and 2013. And it will be all downhill after that.

Ron P.

Ron, thanks for the insights. One of the things that brought me to TOD was trying to decipher how all the crosscurrents of the financial world would interface with oil production and prices. When it comes to investing in alternative energy strategies, it is very difficult to figure out how this will all play out and the timing. Just like every oil company looking at high cost unconventional oil plays, I have been trying to figure out when the price floor will be stable enough to launch a biomass business. Since capital is scarce, pulling the trigger too soon can be fatal. On the other hand, if prices are low for too long, people won't have the funds to invest in alternatives no matter how robust the rate of return in the future when prices eventually rise.

It really is a shame that the US is putting all it eggs in the monetary/military basket rather than working to reduce the energy dependence that drives the need for all the games in the first place.

I see depletion overtaking new production in late 2012 and 2013. And it will be all downhill after that.

In that case, how can you say that decline started in June 2012? Shouldn't the decline start next year?

No I believe that late 2012 is part of this year. Actually June is not late 2012 but production will be down quite a bit in June from the peak in the first quarter of the year. But why are you so pickey? The peak will be early 2012. Or hell, I might be off a few months. I am calling peak in 2012... Okay?

Ron P.

I wasn't being picky. Sometimes people make typos (2012 instead of 2022, etc). I just wanted to make sure I correctly understood what you were saying.

What do you think the decline rate will be after the peak?

I expect the decline to be in the range of 1 percent for the first two or three years. Then I expect it to pick up to around 3 percent or so. But there are wild cards that come into play after three or four years, some exporting nations will cut back, hoarding the oil for themselves. Oh they will still export enough to get a handsome income but not export all they could if they were producing flat out. That could cause the rate of decline to be in the neighborhood of 5 percent or so. That will be catastrophic.

Ron P.

For some reason, this coincides with my prediction that around 2015-2016 we will get an economic collapse due to sovereign debt crisis. Governments will be unable to roll over debt, they will print a lot of money, and the value of paper money will be mostly destroyed. We are all Greek and Spaniard; we just haven't realized it yet.

I think those who listen to Stoneleigh and stay in cash will see their wealth destroyed. A major commodity spike is coming (oil can go to $200/barrel if its purchasing power is devalued).

I will think about it, and try to come up with a post. I try not to be too over the top, because I have a number of sites copying my posts besides TOD and the standard "peak oil" sites. Non-peak oil sites that copy my posts include Business Insider, Forexpros.com, Financial Sense, OilPrice.com and recently OilVoice.com from Britain.

That's really too bad Gail. I wish you had a second blog, under a pseudonym, where you would feel free to go as far over the top to your heart desires. I would love to read your "over the top" opinions. However I would still bet that they are not as far over the top as mine. ;-)

Ron P.

I suppose I will end up with some posts that are more over the top than others, and the various sites can skip them if they choose. All of the various sites "found me"--I didn't go looking for them.

Ron it would be great to see you and others here that are interested in how resource depletion will affect the whole global system in the comment section at Gail’s blog as well as the blog of George Mobus entitled Question Everything.

http://ourfiniteworld.com/

http://questioneverything.typepad.com/

Mark, I only occasionally comment on other blogs. However I can answer your question right here. Resource depletion will be disastrous for the welfare of all the world's nations and all the world's people. We are deep into overshoot and we are depleting all the world's natural resources, not just oil.

We will hit a brick wall and when it happens it will be fast, not slow as many believe. When will it happen? I would guess, and it would be a guess, within the next ten years. It will come within 5 to 15 years after peak oil becomes an obvious fact in the rear view mirror. How long will it take? Not long, weeks to months probably but a very few years at the most.

However....

"All I say is by way of discourse, and nothing by way of advice.

I should not speak so boldly if it were my due to be believed."

-Michel de Montaigne

Ron P.

no no , not screeching - more of a phut phut bang - quite roll to stand still .......:-)

Forbin