Some more natural gas information

Posted by Heading Out on November 16, 2005 - 1:32am

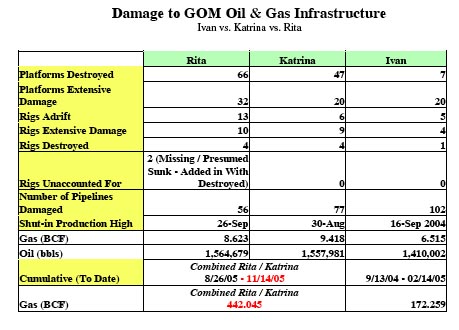

The current lost production is given by the table

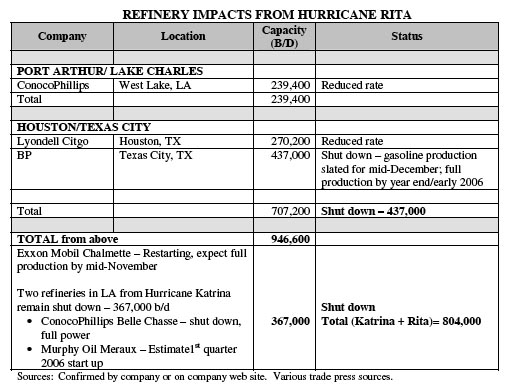

While the refinery situation, which has a little good and bad news, is also updated.

In the same way as oil must be refined before it can be used, after gas comes from the ground it has to be processed.

Even if platforms and pipelines are either unaffected or readily restored to service, the gas may not be able to flow to market without treatment. However, bypassing inoperable plants and redirecting flow to operational plants has mitigated the impact of the shut-ins. In 2003 (the latest year with complete data), almost three-fourths of total U.S. marketed gas production was processed prior to delivery to market.At present the US has 3,229 Bcf/d (3.229 Tcf) in storage (4% above the 5 year average). The EIA expects that natural gas production will be around 19.1 Tcf in 2005. Demand was originally expected to increase by 3.7% this year, but, due to the high prices is now expected to drop about 0.8%, over the 22 Tcf consumed in 2004, which included about 4.1 Tcf of imports, about 0.65 Tcf of which is LNG. Note that while this averages 60 Bcf/day demand is quite seasonal. This leads to stock draw downs being required in January and February. In 2003 these were 841 Bcf and 676 Bcf respectively leaving, by the end of March, only 730 Bcf in working storage. Industrial demand is however dropping due to the high prices, by about 8%, while residential demand can also be expected to decline.A number of processing plants in Louisiana and Texas, with capacities equal to or greater than 100 million cubic feet per day, are not active. These plants have an aggregate capacity of 6.45 billion cubic feet per day (Bcf/d), and they had a total pre-hurricane flow volume of 3.81 Bcf/d.

A number of non-operating plants with a total capacity of 0.90 Bcf/d are operational, but are not active owing to upstream or downstream infrastructure problems or supplies being unavailable. These plants had flowed 0.28 Bcf/d before the hurricanes. A number of the inactive plants are expected to be operating within 2 weeks. Based on updated data, the incremental available capacity at that time would be 2.30 Bcf/d with pre-hurricane flow of 1.06 Bcf/d. Based on updated company information, pre-hurricane flow volumes indicate that the average utilization of the non-operating plants was roughly 59 percent.

While these declines will reflect a switch to other fuels (unless the companies move abroad where the gas, used as a feedstock, is cheaper) that change may, in turn, impose unanticipated loads on other parts of the energy network.

Incidentally, while these last couple of posts have shown that the situation in this country is shaky at best the IEA is expecting that the demand for natural gas will exceed that for coal by 2015. They see the production coming from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) where production will grow from 14 Tcf in 2003 to 22 Tcf in 2010, and this will then be exported as LNG. However they throw in the caveat that domestic demand in the source countries may also rise considerably (particularly if they take in the industries that are fleeing the US because of prices).

Looking at the bigger picture, it looks like we'll probably get through this winter OK, but what happens in the next few years? I'm really concerned about the 31% decline rates and the fact that half of the NG we'll need in 2012 hasn't been discovered yet. I think that it won't take long for the fuel switching, conservation efforts, and industry moving overseas to be swamped by the lack of supply.

What's the pace of new LNG projects? Peter Dea talked about more LNG coming in the next few years but didn't quantify it. Does anyone here know how much is coming and when?

Anybody have any figures on how much NG is left in North America??

Secondly, it appears there has been a 4.5% demand reduction in Natural gas (no +3.7% + -0.8) at present. Is this enough reduction to make up for the lost production from the damaged infrastructure going forward?

In the midwest demand was as close to 0 as you could get for this time of year, up until yesterday when it turned seasonably cold. I suspect that a great deal of the reduction in NG use could be attributed to not drying grain commodities and not needing heat for buildings. There was no need, due to temps in the upper 70's, high wind and no rain through mid November. It is very unusual to have those conditions, over most of the midwest for all of September and October.

Demand may have gone down, but to link that to higher prices might be a bit premature. Moving forward demand may not be much different than last year if the weather stays cold.

If the weather cooperated, lots of drying might not have been necessary. The farmer would have gotten lucky...this year. Don't count on it again, though...

Elevators and buyers pay by weight (a bushel volume) based on 16.5% moisture. This moisture allows the kernel to be stable (won't germinate, typically will not mold) but flexible enough to handle without breaking. A farmer is "docked" for moisture above 16.5%, the elevator is buying excess water.

Corn kernels naturally lose moisture when mature, when all the starch is deposited. Warm (70's F), dry and especially windy weather dries grain much faster than say 45 F with intermittant showers every few days.

As a side note. Not all volume of corn of the same moisture will have the same weight. The starch can be deposited very densly or not as dense in the same size kernel. This is called "test weight" and there are premiums or dockage for test weight as well as moisture when sold. Often high moisture corn will have low test weight as well so a farmer might get docked twice on sale of that grain.

Some years farmers are harvesting corn over 20% moisture. This happens because they have contracts to deliver, it was a cool fall delaying maturity, it has been raining, and soon it will freeze. High moisture corn that freezes often losses quality through cracking, breaking and is more likely to mold, and usually has very low test weight.

Farmers can sell their high moisture corn to an elevator but will be docked for all the moisture and quality issues. Alternatively they could harvest high moisture grain, run it through their own grain bin, with heat and air, to dry to 16.5% and then deliver to an elevator. Typically large farm operations have high capacity driers and can dry cheaper than than the elevator. Cheaper in this case is the cost of NG vs the reduction in price per bushel an elevator would pay for high moisture.

Farmers don't want to sell corn much below 16.5% moisture because they get paid by weight. Over drying or waiting too long to harvest costs money at the elevator because they will be delivering less total weight per acre than if it was 16.5% moisture. Elevators also don't like super dry grain, say below 14% because it breaks and makes too much dust which is explosive. So farmers (you guessed it) get docked on price if they are too low or too high in moisture.

Farmers carefully monitor their fields and when moisture is at or near 16.5% they harvest that field. Farmers always plant multiple varieties that mature at slightly different times based on growing conditions. When a field (or variety) is ready they harvest as fast as possible and deliver to an elevator. We are talking hundreds of acres per day per combine.

Combines, tractors and 80,000 pound tractor trailers all use huge quantities of diesel to harvest and move this grain. But the real energy hog in the fall is typically drying costs. At some point farmers can't wait anymore for mother nature to dry the grain. They have to do it artificially or they start losing money. This year was very unique in that almost the entire crop was harvested without need of artificial drying.

Farmers could wait for all their corn to be close to optimum price for sale (based on % moisture) before combining. This was doubly important this year because it was the second largest corn crop ever harvested in the U.S.. A lot of NG didn't get used this year that usually would have. So thank mother nature (at least in part) for keeping NG stocks high until now.

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/10066397/

And Bunge, along with Cargill, Riceland have a reputation for blending (wet and trashy grain).

Yes, the midwest can get powdery dry in the fall. Relative humidity can get in the single digits in the 60's after frost at dawn. But that often cycles with rain events as we move towards winter, when the humidy is always low. Even if relative humidity is high, there is not a lot of water in 20 F air!

I understand your perspective. I lived in south Texas for awhile and the winters were MORE humid than the summers. Mold a constant concern year round.

Natural gas prices went up quite a bit today. Is this the beginning of something?

http://peakoil.blogspot.com/2005/11/uc-san-diego-economist-hamilton-weighs.html

Well, he's not quite there yet. Peak oil means the same as last year, and we will produce more this year than last. Actual peak won't last long anyway, post-peak is where it gets really interesting.

On the other hand, his views are a lot closer than the markets. He notes that the futures markets predict lower prices, beginning in a year or so and continuing lower indefinitely. The futures markets' view is pretty rosy right now (but they do react quickly to fresh data). He points out that investors who believe in peak oil can make a lot of money buying the futures. I think most peak oil investors (eg myself) prefer to invest in E&P companies, the majority of which have stock prices too high for their fundamentals, meaning buyers must be expecting higher prices are coming.

He is clearly following the discussion, which is good. We have a ways to go before the going gets rougher.