Playing detective with Saudi production numbers

Posted by Heading Out on December 15, 2005 - 11:42pm

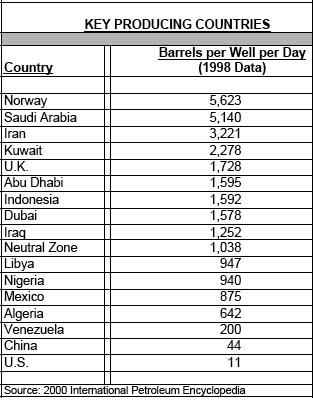

Let me point you in the direction of where some of the numbers can be found since this is one of those detective games that can get quite engrossing. I first ran into this topic reading Matt Simmons article on Giant Oilfields (It is a pdf given on Jan 9, 2002). He gave a table on the relative productivity of wells in different countries.

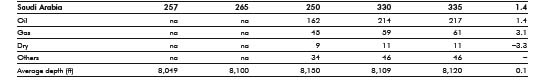

Unfortunately life now gets a bit complicated. For to determine the increase due to the new wells you have to make an assumption as to how much the existing wells have declined, and subtract that revised production from the new years production and divide by the number of wells, to reach the new number for individual oilwell production.

If we take the Saudi numbers, that a rig will drill a conventional well in 21 days, and a MRC well in 40-50 days (from the CSIS meeting) then one can project that a rig can drill somewhere between 6 and 12 wells a year. Matt Simmons said at the Denver meeting that he had thought they were doing about 10 until he went there and found that the number was about 5 wells per rig per year.

Well we can find how many are drilling by going to the Baker Hughes table (excel spreadsheet) where one finds that there were, in November, 37 onshore and 6 offshore rigs drilling. (The numbers are going up). Of these 33 are oil and 10 are drilling for gas).

So this is where we start trying to play a conjectures game. I had calculated, based on production data, that the average well in Saudi Arabia now produces around 4,000 bbd (rounding since I can't immediately find the spreadsheet). So we say that we have 33 rigs drilling for oil. Let us say that they average 7 wells each for the year. Then we have a total of new wells next year in Saudi Arabia of 231 oilwells. If they each produce 4,000 bd, then the total of new oil being produced is 4,000 x 205 (allowing for dry holes) or roughly 820,000 bd of new production.

The problem with this number, as I have posted before, is that this production is very close to the Saudi-reported current field declines (800 kbd the combined increase in production from Qatif and Abu Sa'fah), which makes it hard to see how they can, prior to a number of new rigs arriving, increase their production by the planned amount next year. But this is still based on a couple of assumptions, though not, I believe, unreasonable ones.

The critical numbers are the individual well production numbers, and these appear to be steadily decreasing as the fields that are being exploited get smaller or older.

Incidentally, while I have done this only for the Saudi data, the sites I have cited allow the same exercise for other countries.

do they feel there is a problem with lack of demand or have they been pushing their fields hard enough that they must pull back production? do you foresee a lack of demand with the US and asians wanting to fill their SPR's, as well as the usual buildup before the summer driving season?

Gasoline prices at the pumps here dropped to $1.999 during the week ending December 9th, so I'm not a bit surprised that gasoline consumption spiked back up.

It remains to be seen what the quantity demanded will be at various prices (and how it changes over time if we see prices move higher, but then stay relatively stable at some higher price). I'm actually really interested to see what consumption choices people make when faced with higher prices.

I'd like to suggest a comparision between the mean individual field production at this stage in Saudi Arabia to that of the US-48. Today Saudi Arabia has around 2600 oil wells each producing 4 000 bbd on average. In which year was the lower-48 at this stage?

Remeber that these two regions probably have a very similar URR, and today there are more than 230 000 wells in the lower-48, each producing 20 bbd on average.

I've read Twilight in the Desert, and my inclincation is not to believe Gilbert, but still I wonder what he's basing that claim on. As is mentioned in any analysis of this kind, the data just aren't available to really know for sure what they can do. Gilbert was the chief reservoir engineer for BP, so I have to believe he knows a thing or two.

1) Colin Campbell does not trust BP.

For reserves to stay the same despite production means production has to have been exactly matched by new discoveries or by reserve revision.

2)So I come to the issue of confused dates. An oil field is found when the first borehole is drilled into it. An oilfield contains what it contains, for the simple reason that it was filled in the geological past. Consequently, all the oil ever to be recovered from it, whatever the technology used and whatever the economic conditions, is logically attributable to the first discovery. After all, if we had not been born, we would not have a career of any kind. So I think that the date of a field's discovery is quite as important as the amount of oil or gas it contains...

http://www.feasta.org/documents/wells/contents.html?one/campbell.html

3) On Water Cut-Technology that only hastens the day...

"For example, I'm working a lot with Saudi Aramco. Their problem is that they have four or five fields that are more than 50 years old. Process plant is designed for a water-cut of maybe up to 30%, but they have 70% and 90% water-cut (My Edit-Ghawar maybe?) in some places.

by Jeremy Cresswell

The Press and Journal

North Scotland

Courtesy LATOC

http://www.kenai-peninsula.org/content/view/249/79/

And BTW-how much NatGas does it take to produce a blast that can be seen 100 miles.-The pipeline exploded just before 2 a.m. near the intersection of U.S. 180 and Texas 16, about 12 miles west of Palo Pinto.

http://www.chron.com/disp/story.mpl/metropolitan/3529210.html

I'm familiar with the issues of anomalous reserves data in OPEC and with high water cuts in Ghawar and other Saudi fields. I think Simmons makes a very compelling argument, but he and HO and Stuart always add the disclaimer that whatever conclusions they draw are based on incomplete data. That is, they could be very wrong.

Gilbert is also a peak oiler and evidently has reached a quite different conclusion about what SA can do. I myself am not in the oil industry and don't have access to the same data (or time to analyze them), so I have to try to wade through what the different parties are saying and make some sense of it all. As I said, I find Simmons's take on SA convincing, but I wonder what's behind Gilbert's claim.

I think we probably want to be a little more cautious in extrapolating the Texas example. For example, Samotlor went into decline in 1980, but West Siberia as a whole didn't peak until 1988-89 (because they brought on a slew of other fields).

It is these considerations from the bottom-up that suggest to me that the Hubbert linearization predicted slow declines might be plausible - there's a lot of oil in both Saudia Arabia and Russia that is being held back just because it's owners aren't in a great rush to develop it. Probably a good thing for everyone in the long run.

If you're going to up the overall production volume, you have to increase the injection volume even more to flush the reservoir....

Just something else to lower that 820,000 figure another 20% or so!!

One question I have though: were these numbers derived from merely dividing the country's total production by the total number of wells in existence? If so, might some of those wells in the denominator include inactive or older marginal wells, thus dragging the production-per-well ratio down? In which case, it might not give quite a true picture of what actively producing wells are actually producing.

It would be helpful if you could clarify this point.,

I wonder if they will sell "winter gas" year round now? Doesn't refining sour crude produce extra sulphur emissions at the plant or out the tailpipe? Doesn't refining heavy crudes have a lower EROEI and higher greenhouse gas emissions per gallon of gasoline? When the oil companies borrow from the SPR do they get to repay what they borrow with heavier/sourer crude? If so, this is a sweet deal for them.

Consider that world product consumption is higher over the past several months, during which crude prices have slid, providing a logical explanation why some OPEC members think production should be cut.

It's not often that US President George W. Bush is seen walking hand-in-hand with anyone but his wife Laura. But [Monday], he readily took Crown Prince Abdullah by the hand as the Saudi leader arrived at the President's Texas ranch.

(Photo)

AP

George Bush and Prince Abdullah stroll through spring flowers at the Bush ranch in Crawford, Texas.

The hand clasp with the oil kingdom's 81-year-old de facto ruler had two objectives: a break from recent record-high world oil prices, and a message of U.S. support for the Saudi royal family as it faces a growing internal terrorist threat.

... White House National Security Adviser Stephen Hadley, who praised the Saudis for their "very ambitious" $50-billion plan to expand output from the current 10.8 to 12.5 million barrels a day by the end of this decade and eventually to 15 million barrels a day. Mr. Hadley also announced that the US and Saudi Arabia have "established a joint committee, to be chaired by Secretary [of State Condoleezza] Rice and Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Saud Al Faisal to discuss a range of strategic issues important to both sides," according to the "Washington File" published on the State Department's website.

I feel Pres. Bush is way ,way out of his comfort zone walking thru the garden holding hands, like PLEASE more oil. Maybe they will not be "together" before long. Tight relationships often go thru major switches.

This committee with Ms. Rice looks like our way of keeping close tabs on them.

That is the plus side of the equation, at the same time it would be nice to have better information on the downside - existing well declines , other than the occasion ballpark number.

If these are all factored in, wouldn't the ERoEI drop considerably--even exponentially? I.e, couldnt we have (rosiest scenario) at the wellhead only a small rate of decline or even a plateau in the near future and yet see a significant decline in net production of refinery products?

Heavy and sour crudes require a greater energy and capital input to produce useable products. It is certainly the case that, all else being equal, an increasing proportion of sour crude in a fixed volume of supply will reduce net post refinery energy.

The picture is less clear for heavy crudes, which contain more energy, but require more energy (and capital) input to create useful products. I haven't seen a comparision on of energy input versus energy output for different crude classes. I'll try to find something.

You are correct that post refining net energy would be a more important consideration than crude volume. My guess is that the difference could be significant, but not exponential.

Go catch Richard Rainwater in Fortune - if the article is correct, he's out here with us - literally: the sidebar claims TOD is one of 5 blogs he goes to daily.

If you stop by Richard, please say "Hello"

Sorry - did a scoop search and no mention showed, but apparently it was discussed in yesterday's Open Thread.

Please go back to what was being discussed - I'll crawl back into my cave....

The Saudi and other OPEC throttling sure came in handy in the massive demand surge of the 70s, which Simmons describes as a "runaway train". Oil was $1.80/barrel before this and went to over $18 in '79 before the Iranian supply shock sent it to $40. The Saudis strained their excess production capacity to their then considerable limits so much so that it precipitated two secret Congressional hearings in '74 and '79 on the reservoir damaging overproduction by Aramco that was then run by the big American oil companies, as documented by Simmons. Think about it. Oil pricing climbed over 1000% with the throttle opened wide to reservoir damaging levels to "control" this 10 year demand surge. Now we face a new demand surge from China, India, and many other factors; and we have no throttle. You hear so much about how demand destruction will serve as the cure for high oil - not to worry. High oil is the cure for high oil. But it didn't work very well in this past demand surge. Simmons points this out (p57-58) noting that, despite the accepted wisdom that high oil during this time damaged the economy and produced a steep drop in oil demand, actual oil demand increased 44% during this phenomenal price climb. how can we expect a measly climb to $100 from $30 to produce enough demand destruction to solve the problem in an economy that's much stronger than the wretched 70s economy? How much can we rely on demand destruction and the free markets to control high oil? We will have to rely on demand CONVERSION more than on demand destruction - that is conversion of demand to coal derived fuels and other sources that started to take place under Ford and Carter, but most unfortunately went nowhere because we had plenty of cheap oil left.

Another source of complacency is this notion that the Saudis can ramp production up to 15 mbd or higher from the current 10 or so by drilling previously mothballed or undeveloped fields. Simmons argues convincingly that this is unlikely, pointing out that these are poor producers or have problems that have focused efforts on the tried and true elephant fields in current production. If these other fields are so prolific and easy, why focus all the effort on wringing the last easy oil out of the spent, peaking fields with no fresher production geared up and ready to take its place, Simmons argues. But let's assume for the sake of argument that the Saudis can ramp it up to 15 mbd in just a couple of years. World oil demand is about 85 mbd and is increasing at over 2% per year. Do the math and you see that, with oil from elsewhere being flat at best, the 2 mbd world demand increase per year goes through the Saudi ramp up from 10 to 15 mbd in just 2.5 years - about how long it would take them to do the increase if they are lucky! What kind of solution is this? Even a ramp up to the high teens would have a good portion go to offsetting declining production elsewhere and the remainder would be quickly soaked up by the rate of global demand increase. Even if all our detective work finds it feasible, how much can we rely on a Saudi ramp up to control high oil?

Why we are not in a national emergency program to build coal conversion plants, I guess I'll never understand.

Perhaps you might draw tentative conclusions ;)

Then wonder what their plan A or B might mean for you.