Stumbling Blocks to Figuring Out the Real Oil Limits Story

Posted by Gail the Actuary on August 15, 2013 - 2:49am

The story of oil limits is one that crosses many disciplines. It is not an easy one to understand. Most of those who are writing about peak oil come from hard sciences such as geology, chemistry, and engineering. The following are several stumbling blocks to figuring out the full story that I have encountered. Needless to say, not all of those writing about peak oil have been tripped up by these issues, but it makes it difficult to understand the “real” story.

The stumbling blocks I see are the following:

1. The quantity of oil supply available is primarily a financial issue.

The issue that peak oil people are criticized for missing is the fact that if oil prices are high, it can enable higher-cost sources of production–at least until these higher-cost sources of production prove to be too expensive for potential consumers to buy. Thus, high price can extend oil production for longer than would seem possible, based on historical patterns. As a result, forecasts based on past patterns are likely to be inaccurate.

There is a flip side of this as well that economist have missed. If oil prices are low (for example, $20 barrel), the economy is likely to be very different from what it is when oil prices are high (near $100 barrel, as they are now).

When oil prices are low, it is likely that oil production can be expanded rapidly, if desired, because it takes little effort to extract an additional barrel of oil. In such an atmosphere, it is easy to add jobs, because new technology, such as cars and air conditioners made and transported using such oil, is affordable. Growth in debt makes considerable “sense” as well, because additional debt enables more oil use. It is likely that this debt can be repaid, even with fairly high interest rates, given the favorable jobs situation and growing economy.

With high oil prices, there is a constant uphill battle against high oil prices that rubs off onto other areas of the economy. Businesses tend not to be too much affected, because they can fix their problem with high oil prices by (a) raising the prices of the finished goods they sell (thereby reducing demand for their goods, leading to a cutback in production and thus jobs) or (b) saving on costs by outsourcing production to a lower-cost country (also cutting US jobs), or (c) increased automation (also cutting US jobs).

The ones that tend to be most affected by high oil prices are wage-earners, who find that their chances of obtaining high-paying jobs are lower, and governments, who find it increasingly difficult to collect enough taxes from wage-earners to pay for all of the promised benefits.

2. The higher cost of oil extraction in the future doesn’t necessarily mean that the price consumers can afford to pay will rise.

In peak oil groups, I often hear the statement, “When oil prices rise, . . .” as if rising oil prices are a given. Businesses may be afford to pay more, but individuals and governments are finding themselves in increasingly poor financial condition. Quantitative easing isn’t getting money back to individuals and governments–instead, it is inflating the price of assets–a temporary benefit until asset price bubbles break, as they have in the past, or interest rates rise.

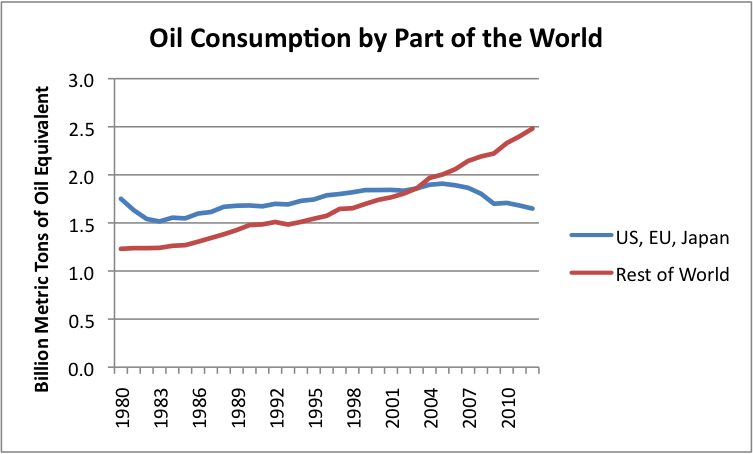

The limit on oil supply is what I would call an affordability limit. Young people who don’t have jobs can’t afford to buy cars. If young people graduate from college with a huge amount of educational loans, they can’t afford to buy houses either. Within the US, Europe, and Japan, we seem to have already hit the affordability limit on the amount of oil we are consuming. Economic growth is low, as oil consumption declines.

The risk, as I see it, is that the price consumers can afford to pay will drop below the cost of extraction. It is this drop in oil price that will cause supply to fall. If the drop in price is very great, we could see a very rapid decline in oil production, especially in countries with a high cost of production, such as the US and Canada. Some oil exporters may find themselves in difficulty, because they are no longer able to collect the tax revenue they were depending upon. This could lead to uprisings in the Middle East and possibly lower oil production in affected countries.

I should point out that it is not just the peak oil community that seems to think rising oil prices can continue indefinitely. Economists and those forecasting climate change seem to share this view. If oil and other fossil fuel prices can rise indefinitely, then a very large share of fossil fuels in the ground can be extracted.

3. There is widespread confusion about what M. King Hubbert really said about the shape of the decline curve.

M. King Hubbert is known for showing images of world oil supply which seem to show that oil supply will rise and then fall in a symmetric pattern. In other words, if it took 50 years for oil production to rise from level A to level B, it should also take 50 years from oil production to fall from level B back to level A. This relatively slow downslope gives comfort to many people concerned about peak oil because they believe that the slow downward path in oil production will be helpful in mitigation strategies.

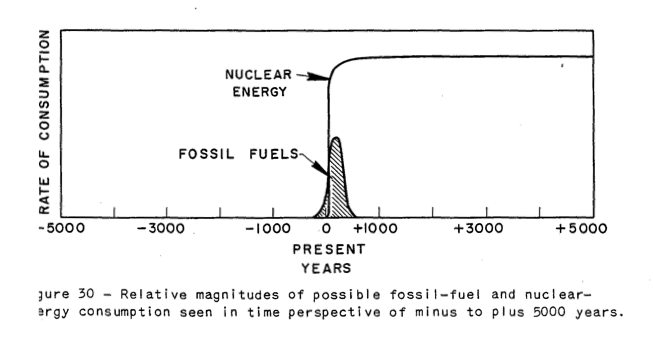

In fact, if we look at Hubbert’s papers, we discover that Hubbert only made his forecast of a symmetric downslope in the context of another energy source fully replacing oil or fossil fuels, even before the start of the decline. For example, looking at his 1956 paper, Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels, we see nuclear taking over before the fossil fuel decline:

Hubbert’s 1976 paper talks about solar energy being the substitute, instead of nuclear. In Hubbert’s 1962 paper, Energy Resources – A Report to the Committee on Natural Resources, Hubbert writes about the possibility of having so much cheap energy that it would be possible to essentially reverse combustion–combine lots of energy, plus carbon dioxide and water, to produce new types of fuel plus water. If we could do this, we could solve many of the world’s problems–fix our high CO2 levels, produce lots of fuel for our current vehicles, and even desalinate water, without fossil fuels.

Clearly the situation today is very different from what Hubbert was envisioning. Neither nuclear or solar energy is providing a sufficient substitute for our current economy to continue as in the past, without fossil fuels. We have a huge number of cars, tractors and trucks that would need to be converted to another energy source, if we were to move away from oil.

If there is not a perfect substitute for oil or fossil fuels, the situation is vastly different from what Hubbert pictured. If oil supply drops (perhaps in response to a drop in oil prices), the world economy must quickly adjust to a lower energy supply, disrupting systems of every type. The drop-off in oil as well as other fossil fuels is likely to be much faster than the symmetric Hubbert curve would suggest. I wrote about this issue in my post, Will the decline in world oil supply be fast or slow?

4. We do have an estimate of the shape of the downslope when there is not a perfect substitute the resource with limits.

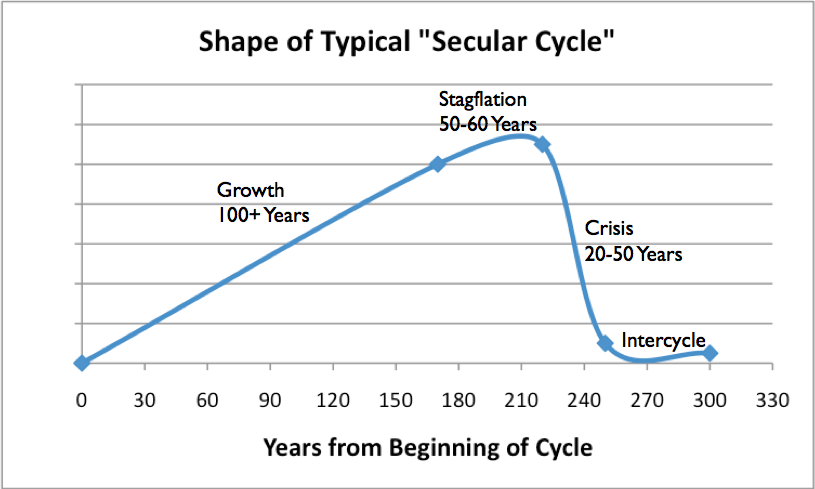

There are many historical examples of societies that found a way to greatly increase food supply (for example, by clearing land for new fields, or by learning to use irrigation). Peter Turchin and Sergey Nefedof researched the details underlying eight agrarian societies of this type, documenting their findings in the book Secular Cycles.

These researchers found that at first population was able to increase, because of the greater ability to grow food. Population typically increased for well over 100 years, as population gradually expanded to match the new capacity for growing food.

At some point, the economies analyzed entered a period of stagflation, during which wages of the common worker stagnated, because an early limit had been reached. Population had reached the level the new resources could comfortably support. After that point, growth slowed. New babies were born, but additional area for crops was not being added. Adding more farmers didn’t increase output by very much. Debt also increased during the stagflation period. The chart below is my estimate of the general pattern of population growth found by Turchin and Nefedov, in the years following the addition of the new capability to grow food.

Eventually, a crisis period hit. One major issue was a continuing need to pay for government programs had been added during the growth and stagflation periods. With the stagnating wages of workers, it became increasingly difficult to collect enough taxes to pay for all of these programs. Debt repayment also became a problem. Food prices tended to spike and became quite variable. Governments became increasingly susceptible to collapse, either because of outside forces or internal overthrow. Population was reduced through a combination of factors–more wars and a weakened population becoming more susceptible to epidemics.

It seems to me that our current situation is somewhat analogous to what has occurred in these secular cycles. The world began using fossil fuels in significant quantity about 1800, and reached the stagflation phase in the early 1970s, when US oil production began to decline. We are now encountering the classic symptom of resources not rising as fast as population–namely, wages of the common workers stagnating. Fossil fuel prices tend to spike and be quite variable. Government financial problems we are seeing today sound very similar to what past civilizations experienced, when they hit resource limits.

We don’t know that our current civilization will follow the same shape of downslope as earlier civilizations that hit limits, because our economy is not an agrarian economy. We are now dealing with a globalized civilization that depends on international trade. Jobs are much more specialized than the past. But unless there is a miraculous growth in cheap energy supply that can fix our problems with young workers not finding good-paying jobs, there seems to be a good chance we are headed in the same general direction.

5. High Energy Return on Energy Invested (EROI) is a necessary but not sufficient condition for an energy source to be a suitable substitute for oil.

We are dealing with a complicated financial system, but EROI is a one-dimensional measure. It can tell us what won’t work, but it can’t tell us what will work.

Any substitute for oil (for example, a transition to battery-operated cars) needs to be considered in the context of what the total cost will be of a transition to a new system, the timing of these costs, and who will pay these costs. It is important to consider what impact these costs will have on those who already are at greatest risk–namely, individuals who are having difficulty earning adequate wages, and governments that are finding it increasingly difficult to pay benefits that have been promised in the past. If individuals are being asked to pay higher costs, this will reduce discretionary income to be used for other purposes. If a government is already stressed, adding energy related stresses may “push it over the edge,” making it impossible to collect enough taxes for all of the promised programs.

6. It is easy to be influenced by the fact that everyone likes a happy ending.

People coming from a peak oil perspective often accuse the main street media of putting forth a “happily ever after” version of the oil story. But I think there is a temptation of the peak oil community to put together its own “happily ever after” story.

The main street media version says that the economy can continue to grow, and we can continue to drive cars and go to our current jobs, despite a need to change to different kind of fuel supply.

The peak oil version of the story often seems to say, “If we conserve, and learn to be happy with less, there won’t be too much of a problem.” Some seem to suggest that hoarding solar panels for our own use can be helpful. Others seem to believe that society as a whole can be transformed by adding more solar and wind power to our current electrical system.

The difficulty with adding a new energy source in quantity is that we don’t have any such energy source that can truly act as a cheap substitute for oil. If solar PV or wind, or some other new energy source were truly a good substitute for fossil fuels, such a fuel would be exceedingly cheap and could be used with today’s vehicles. Governments could improve their financial condition by taxing this new energy resource heavily. It would be obvious to everyone that by adding much more of this miraculous new fuel, we could add many more good-paying jobs, especially for our young workers.

Unfortunately, I cannot see that we have found a good oil substitute. Instead, quantitative easing is temporarily hiding financial problems of governments and individuals by forcing interest rates to be very low. This makes cars and homes more affordable, and keeps the amount of interest paid by the federal government very low. We know that these artificially low interest rates are temporary, though. Once they “go away,” tax rates will need to rise, and asset prices (stock prices, bond prices, and home prices) will drop. Oil prices may very well decline below the cost of production. We will again be at risk of heading down the “Crisis” slope shown in Figure 3.

The Oil Drum Going to Archive Status – Important Story Still to Be Told

The peak oil community is filled with many dedicated volunteers coming from a variety of backgrounds. I particularly commend The Oil Drum volunteers for sticking with the issue as long as they have. Many of them have discovered at least some of the pitfalls of the traditional “peak oil” story listed above.

I will continue to tell the story of oil limits on my site, Our Finite World. In the near future, I am also giving a number of talks about the issue to actuarial groups. I need to get the story documented in other formats as well–in book form and in the actuarial literature. The fact that The Oil Drum is going to archive status doesn’t mean that there isn’t a real, important story to be told. It isn’t quite the original peak oil story, but it is closely related.

This article was originally posted at Our Finite World.

There's another issue and that is the oil companies' debt carrying capacity. As oil prices are, generally, a reflection of current production costs they have the previous exploration and development costs baked in. New exploration etc has to be financed out of profits or debt. Debt is fine when new oil costs more or less the same to develop as old oil and profit margins are high. As production costs have ramped up, retail prices have been unable to keep up without crashing the economy and the oil companies have had to finance the exploration themselves, out of both revenues, reducing profits, and debt. They are now reaching the point where they are debt-saturated and unable to take on any more. Those expecting the current drilling boom, as distinct from a production boom, are in for a nasty surprise.

Oil company profits go down, their ability to drill for new, even more expensive oil is contrained either by falling share prices or unserviceable debts, and the PO process of falling production resumes, quite soon.

You are right. Debt carrying capacity is part of the problem as well. The oil majors have reported lower earnings recently, partly because the cost of extraction has been rising, while oil prices have not (and partly because of a shift to shale gas, which has not very profitable). I was trying to keep the post short and simple, so I didn't get into everything. This issue is related to my Item (1), oil supply being a financial problem.

Small oil companies would seem to be particularly affect by debt carrying capacity. Once this gets maxed out, a company either has to find a buyer with deeper pockets, or quit drilling.

I haven't researched the issue, but I think this may be becoming an issue for some of the national oil companies as well. Some of the governments have been using these companies to generate cash, leaving them without much money for reinvestment. The move by Mexico to bring in outside companies may be related to this kind of issue (I should look, though). Brazil and Venezuela are other countries that come to mind.

Excellent post. It would have been much better had we adopted policies to force oil to begin its terminal decline in 2005. That would have forced people to pursue alternatives, efficiency, and lifestyle changes while there was still plenty of supply. But instead we pushed as hard as possible to maintain oil levels on a plateau with few changes. This delays the dropoff, but makes the decline much steeper when it occurs.

I am not sure that it would have been much better if we had adopted policies to force oil to begin its terminal decline in 2005. Our financial system depends on economic growth, and financial growth in turn depends on increasing amounts of oil, plus the cost-saving economies that one gets by ever-larger scale of operations.

Regardless of lifestyle changes, I expect that forcing oil supply lower would have resulted in many business failures, huge job loss, and quite possibly government collapses. These changes would indeed to reduced oil usage, but I think we would describe the situation as not at all desirable. A lot of people seem to have the impression that "pursuing alternatives, efficiency, and lifestyle changes" will lead to plenty of supply. I agree that if businesses are closed, and people don't have jobs, we will use a lot less oil. A lot more people will need to move in with relatives, and give up their cars. This is where the energy savings comes from. Some people may die sooner

Somehow, people seem to think that "pursuing alternatives, efficiency, and lifestyle changes" really has an impact. What a person purchases is pretty much determined by income. Reducing expenditures on one item leads to more funds available to purchase other items. Efficiency makes it possible to purchase a bit goods and services, with the same income. The only way it is possible to really reduce energy purchases is to force income lower, usually by laying off workers, and by downgrading full-time jobs to part time jobs. A "good" way to reduce jobs is by closing businesses. Governments will be poorer as well, because of lower tax revenue, so will not be able to afford programs to help the jobless out.

The decline is likely to be steep whenever it occurs. Many of us will likely die. I am not in favor of moving up the time when run into major problems.

And therein lies the rub! Our growth based financial system was already kaput and the longer we tried to keep it going the harder and further the fall. Not adopting policies to start getting off oil back then IMHO was a huge mistake.

All very true Fred. And, I would add that - since there is no real alternative available (see related Archdruid Report this week), it was never truly possible to "get off oil" back then. Or now, for that matter.

The best alternatives are not realistically capable of making the sort of transition that society wants and needs. We have all read many reports, books, blogs, etc., that have tried to show that this techology, or that drilling technique will make all the difference. Cold fusion, Bakken oil, Shale Gas... plus the old standbys of nuclear fission, hot fusion, solar, wind, geothermal, all are raised as the wave of the green future. And yet, despite the obvious gains (particularly in wind power), oil's position and role in the economy remains undimished.

Maybe if we had embraced ALL of the above 33 years ago instead of taking Saint Ronnie the Wrong to our breasts as Savior of the Chicago Economy we might be today in a remotely tenable position. And, of course, if pigs had wings they could fly!

Legjobb reméli, hogy disznosag.

(?not sure about this translation?)

Craig

How is that cold fusion thing working out anyways?

Can I get one yet?

Yes, because when US shale oil peaks we will be in a period of steeper conventional declines.

Moreover, the problem is that since 2005 a lot of investments were done in oil dependent infrastructure which will not generate the assumed financial returns, worsening the debt crisis.

In Australia, governments still plan new toll-ways

http://www.smh.com.au/nsw/nsw-government-to-shoulder-risk-of-10b-westcon...

http://www.linkingmelbourne.vic.gov.au/pages/east-west-link.asp

The fact that governments don't recognize the direction things are headed already means that they are building a lot of new roads around the world, even though traffic is generally falling in "developed" countries. Governments are too poor to finance them, so they make them into to toll roads. These toll roads further reduce the discretionary income of wage-earners. If traffic drops in the future, the new toll roads will not be very much needed, and tolls will be far below expectations. I expect the responsibility for the roads will end up back with the state.

It's a poison chalice trying to model collapse. You don't get any thanks for it if you are right and mocked if you are off by timing or type. It is horribly complicated but the unending drive for governments to rinse their hands of responsibility by privatizing everything is well underway.

Massive price hikes everywhere.

I should add that when I said it would be better to force oil to start terminal decline, I did not mean it would be better for us now. I understand that if we had started reducing oil usage by say 3% per year starting in 2005, we would all be feeling the pain of that decision now. But in the long run it would have been better. As we all felt the pain of living with less oil, we would have more actively pursued alternate energy sources, efficiency gains, and lifestyle changes that provide for happiness with less oil.

You say that, "Many of us will likely die." I agree. That is why this is so serious. Accepting increased economic pains now, if it reduces the steepness of the decline, and thus reduces the numbers that will likely die, would be a great tradeoff.

I see no reason that forcing terminal decline now will change the shape of the decline. We will still have governments and businesses fail, and people losing their jobs. Problems with food and water supply will come earlier.

I expect it will just mean that those people who are alive now will live less long. This will be good for the plants and (other) animals on the earth, but not for humans.

So there is really no reasson to see that forcing terminal decline now will change the shape of the decline? Why not?

Had we reduced oil supply to 97% of the previous year's oil supply every year since 2005, we would be down to 78% of the 2005 rate. All that extra oil would be in the ground, ready to power future combines and tractors when oil supply becomes more scarce.

"Just"? How much will this shorten our lifespans? What will be the remaining human population on earth 40 years from now? 50% of the current 7 billion? Or are we talking only about minimal dieoffs of a few poor elderly people?

If in the near future, for lack of oil, millions or even billions will die, then we ought to save back all the oil we can.

And then put it into our children's combines.

But of course that would require world agreement on an agressive plan to save back oil. Its not very likely. I am only dreaming. But that is what we should do, in my opinion.

I can't see a policy image of what you are suggesting, and it seems to me that it is taking the right goal, but putting the cart before the horse somehow. Sort of like saying 'don't swallow 97% of the food you chew, and you'll gradually be able to reach your diet goals.. (perhaps this is my way of also expressing my deep doubts about tying restraining belts around our stomachs to handle diet problems..)

In any case, I think the way you cut that consumption is with the consumer (and consuming industries) learning to find those reductions and savings, and for them (us) to disdain spending too much on energy purchases, when there are alternative routes that will steadily and eventually put us in much more stable situations (ie, Long-term thinking..)

Therefore, the policy routes would be for promoting this kind of thinking and information, and helping the citizens and business community work towards this goal.

I am suggesting something like a cap and share system. See, for instance http://www.capandshare.org/howworks_basicidea.html.

This would require massive cooperation among all nations of the world. Not very likely, but that is what is needed.

Yes, but how do you get that to happen?

Oil companies supply 80 million barrels a day. If I cut my consumption in half, in the long run, that means nothing. If I convince a billion people to join me, and we all cut our consumption in half, demand would fall. But oil companies could still produce 80 billion barrels a day. Prices would plunge. But surely some people would step in and consume all that cheap oil. Efforts to conserve in the long run often don't accomplish what we want (Jevon's paradox).

So it would require a unified effort in a massive plan such as a universal tax on oil at the source which would be adjusted as high as needed to cutback production as needed.

OK, folks may say I'm a dreamer, but I'm not the only one.

A simple tax on oil Back in the 70's would have eased much of the pain we are seeing today but the public would have ousted any politician that supported such a tax.

People will make sacrifices if they believe in the cause. Lincoln and Roosevelt were reelected during wars.

And, of course, a gas tax is a tiny sacrifice compared to a war.

Smart post, thanks. One quibble: you say "We are now encountering the classic symptom of resources not rising as fast as population–namely, wages of the common workers stagnating," and you seem to be distinguishing this "now" from the period beginning in the 70s, but in fact wages have been stagnating since the early 70s. Now they're starting to decline...

Anyway, thanks for TOD and many years of thoughtful analysis.

You are right. We entered the "stagnation" phase in the 1970s. Now we are actually hitting the decline period.

Besides high oil prices, globalization plays a role in this. Part of the reason globalization can take business away from developed countries is because the Asian countries tend to use a lot of coal in their energy mix, and coal is a lot cheaper than oil. With higher oil prices, we are less competitive on the world market. Also, businesses can outsource their production to these countries, and reduce their costs.

See my post (which I did not get around to submitting to The Oil Drum), Oil Limits Reduce GDP Growth; Unwinding QE a Problem.

Also, businesses can outsource their production to these countries, and reduce their costs.

With this comes an outsourcing of the associated pollution, allowing the false appearance (of the country doing the outsourcing) of being cleaner/greener. However in reality, the overall global result is dirtier.

I agree. Politicians seem to only look at expected impacts within their own country. They often seem to have a different "real" objective - hold down future oil imports - than their stated objective of reducing pollution / making the country greener. Politicians want carbon taxes, not realizing that they make their own country less competitive, and increase the incentive to outsource production to another country. Until there are high taxes on imported goods made in countries using coal, encouraging outsourcing is counterproductive.

Wonderfully clear and realistic post Gail, thanks.

Politicians live for today. Late Roman emperors gave huge donations to the army in order to protect themselves from this same army. I can't remember the exact quote, but Septimius Severus told his hopeless son Caracalla to 'give the army everything and ignore the people'. Caracalla didn't entirely ignore the people, of Rome at least, but taxation throughout the empire rose and after two centuries most ordinary, impoverished, subjects of the empire, had been reduced to serfdom by taxation, while a tiny administrative elite had become richer than ever before in Roman history. They were only too glad to welcome the 'barbarians', because taxation fell and conscription into the army ended. Sorry to be historical, but we are there. Our rich are making themselves richer than ever before, while the ordinary citizens are paying a price they cannot afford through tax, and being reduced to near bondage. Here in Britain we have a government that is both in thrall to the moneyed elite, but also attempting to win the votes of that same elite, by offering large benefits to those with incomes of up to £130,000 to help with their childrearing. Britain is pumping out more babies than any other European country, on the back of benefits, while unemployment and low pay is worsening. Talk about the Red Queen, we live in Lewis Carroll nightmare of political short-termism.

Meanwhile our roads are gradually dilapidating and our government talks of a vastly expensive rail route to link London with Birmingham, and toll roads for the rich.

And nobody seems to know or care. We have a royal baby, endless pop groups, celebrities, murders and sportspeople, and sunshine, and that seems to be enough for now. Meanwhile Brent crude, on the back of real production stressing and the mess in Egypt, has risen by four dollars in the past week. So much for abundant oil...

Thanks Gail.

I've added your other site to my favourites.

Colin

And so we sit back as we run off the cliff, but hey, there is a royal baby. And people find that important?

When cognative dissonance is particularly high, the need for distraction becomes overwhelming. If you are thinking about the royal baby, you are perforce not thinking about economic chaos, limited resources, and widening civil unrest, worldwide.

Here, in the good old US of A, we watch the trials of the horrible criminals who surface from time to time. Or celebrity criminals. In England, of course, it is the new heir to the throne.

It seems to help.

?

Craig

Thanks for your vote of support. It is weird, reading about past collapses, and seeing how similar our current situation is today. It is amazing to me how much the media presents a distorted picture of the situation.

'carbon taxes... increase the incentive to outsource production to another country.... Until there are high taxes on imported goods made in countries using coal, encouraging outsourcing is counterproductive' That pretty much nails it in Australia's case. Look at it by telescope from Mars say. Australia digs up coking coal and iron ore, or alumina/bauxite and thermal coal and sends it to Asia who supply their special ingredient 'lack of carbon tax'. When Australia closes down its steel and aluminium industries it will have to buy back the metal made from its own ingredients, both the metallic ore and the energy fuel. Slightly weird but it makes the domestic emissions figures look better. Of course it wastes a lot of ship fuel and costs jobs but so far nobody is noticing. That's until the rest of the economy can't make up for the jobs or global warming action needs to get serious.

It's pretty easy to see when things took a turn. @1970-1980: US crude oil production peaks; The "Nixon shock", Bretton Woods system ended -

Ten years of costly war, the funding of expensive domestic programs, two decades of infrastructure growth (road/interstate building, etc.), all of these policies were becoming untenable, economically. US oil production peaks - imports rise, as do trade deficits...

Sound familiar? We can't 'refloat' the currency, so we get QE. What's next?

Over the edge?

I need Fred's help with a graphic showing Roadrunner going past the cliff, and yet not falling.

When does our reality begin to set in? How far down is the bottom of the canyon?

Wheeee!!!!

Craig

Something like this perhaps?

http://i289.photobucket.com/albums/ll225/Fmagyar/WileysOlduvai.jpg

The limit on oil supply is what I would call an affordability limit.

Not really . The following link shows the ratio of gasoline consumption and energy goods and services consumption to salary and wages (not including benefits) in the U.S. from 1959 to present.

Although the ratios are elevated today relative to the cyclical lows at the turn of the millenium, they are not unprecedented.

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=2eM

that link takes me to portion of GDP that is wages/salaries not what you said. Pretty sad graph all the same.

In regard to the oil supply response to rising oil prices, as annual Brent crude oil prices more than doubled, from $25 in 2002 to $55 in 2005, what I define as Global Net Exports of oil (GNE*) increased at a rapid rate, from 38.7 mbpd in 2002 to 45.5 mbpd in 2005 (EIA data, as of 7/13), an annual rate of increase of 5.2%/year from 2002 to 2005.

However, in response to annual Brent oil prices more than doubling again, from $55 in 2005 to $112 in 2012, with one year over year decline in 2009, GNE has been below the 2005 rate for seven straight years, at 43.9 mbpd in 2012, an annual rate of decline of -0.5%/year from 2005 to 2012.

*GNE = Combined net exports from top 33 net exporters in 2005, EIA data, total petroleum liquids + other liquids

Good summary of what might happen. Do we have any numbers of how much of the US QE money has flown into:

(a) rolling over debt

(b) asset bubbles

(c) supporting purchasing power of motorists to pay higher petrol prices

(d) oil industry to pump shale oil and gas

The oil and gas industry has now convinced the public that shale oil and gas is a revolution for decades to come. In this context, who will now transition the economy away from oil?

Also important are those fiscal break-even oil prices in the Middle East

14/8/2013

OPEC's average fiscal break-even oil price increases by 7% in 2013

http://crudeoilpeak.info/opec-fiscal-breakeven-oil-price-increases-7-in-...

My understanding of the QE impacts is the direct impact is primarily with respect to shoring up the finances of banks. This seems to help non-US banks as well as US banks, since all of the banks are linked though lending balances.

There are many indirect impacts, because QE makes interest rates lower than they would otherwise be. This means that government finances look better, so they don't need to raise taxes as much as they really should. This affects mostly individuals. QE also makes interest rates on loans to buy assets very cheap. This encourages asset bubbles in real estate and in farm acreage, as well as stock market prices. QE also makes loans for rolling over debt, and for companies drilling shale oil and gas very cheap, encouraging both activities.

The low longer-term interest rates mean that homeowners can refinance their homes at low rates, leaving them more funds to pay for higher petrol prices. The fact that the low interest rates makes home values higher, also makes it more feasible to refinance homes. Fewer loans are "underwater".

So it seems like all four of the items you mentioned are supported by QE, even though none of them are related too closely to banks, which get the direct benefits.

Thanks for the link to your post on the fiscal break-even oil price. This has to do with how high an oil price has to be, for a government to get enough tax revenue from oil exports to balance its books. The discussion you provide relates to OPEC countries, who are of course very important as oil exporters. You link to this study by APICORP research. I understand that Russia also has a very high fiscal break-even, so it too needs very high oil prices.

Hi Gail.

You have been saying this for years and it made me sick to see the article about "peak demand" in The Economist the other week as if a) they'd thought of it first and b) it somehow disproved peak oil. Tragic to see a once-objective publication try to deny the existence of fundamental economic theory.

But even though I think it is a good point, I only agree with it up to a point. It describes how things would go if there were no alternatives. Personally, and just to say it again, I think those alternatives are already hoving into sight. The transition will be dramatic, but disastrous outcomes are by no means inevitable.

Good luck, I will check out your blog some time.

The issue of peak demand has been brought up by others, as well. I wrote an article Peak Demand is Already a Huge Problem back in April to counter some of the silliness. (I don't think it ran on The Oil Drum--I may not have submitted it.)

One article about peak demand (in the sense that the Economist is using it) that has gotten a fair amount of publicity is Peak Oil Demand: The Role of Fuel Efficiency and Alternative Fuels in a Global Production and Decline by Adam Brandt and others. I think there are many tripping points in looking at this issue. One is that the analysis needs to cross several different subject areas to work. Another is that there are about 3 billion Asians, who would be happy to have cars or motorcycles, if the cost could be reduced enough through fuel efficiency. Another issue is that oil consumption is very much related to jobs-if people don't have jobs they can't afford vehicles; if they do have jobs, they often can. And of course, as I have pointed out, oil consumption is already dropping significantly in quite a few developed countries, more or less corresponding to poor job growth or a decline in jobs.

I know Adam Brandt, and have corresponded with him about his new article. One issue is the lack of academic papers explaining what the "real" oil demand situation is.

In my view, in order for the so-called "alternatives" to current fossil fuel system to be successful, they need to be something other than add-ons to the current fossil fuel system. As it is, they will fail at the same time the rest of the system fails, because they depend on fossil fuels to make new ones and to keep the whole system in repair. Alternatives also need to be lower cost than they are. The world depends on high taxes from the oil and gas industry. To be comparable, we need to be able to tax Alternatives in the same way--not subsidize them.

An excellent summary by Gail once again which will be sorely missed when the Oildrum goes into archive mode.

However I suppose I am in the camp of Peak Oil DEMAND optimist as Gail puts it - it is not just a fantasy but reality that the US COULD in very short order save 20% of its oil usage by cutting our waste and investing in Auto Addiction alternatives. For one thing, to start with the first huge waste of oil 5% is wasted on the Pentagon and its Wars, ironically frequently waged to insure access to oil. The Pentagon is the world's largest oil consumer and greenhouse emitter as an Institution. Ironically also the $3 Trillion wasted on the Iraq War to insure US majors access to oil has resulted instead in China getting access to the oil while sectarian violence has re-emerged blowing up oil pipelines and disrupting Iraqi oil production which has only recently exceeded the level under Saddam Hussein.

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/03/world/middleeast/china-reaps-biggest-b...

http://www.theoildrum.com/node/10005

As far as Auto Addiction oil usage which is already declining as peak cars was already reached in 2006, with 79% of Americans already living in urbanized areas a program of just running existing trains, light rail, buses and adding shuttles, bikepaths and safe walkways for the last mile could increase public transit usage by 4 times as was done between 1942-45. Beyond High Speed Rail, just incremental investments to restore service on existing Rails from Boston to Cape Cod has been an overnight success!:

http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/07/16/capeflyer-train-from-bo...

The cost was a mere $1.1 million far less than the cost I see on I-80 in Parsippany of

some highway widening or maintenance project for a few miles costing $5.5 Million.

Then we have other low-hanging fruit like not only gas lawn mowers which could be easily replaced with push mowers requiring 0 oil or electricity, but the huge landscaping trucks pulling trailers of riding lawn mowers which ply upper middle class suburban areas.

How about local push mowers by local High school or even Middle school kids?

The car of the future may be the car of the past. I understand there is something called a sedan chair that operated similarly.

FIne. Suppose the US decreases its demand by 20%, or 30%. That reduces world oil price by a bit, and puts some the extra oil back on the world market, to be bought by others. There are 3 billion Asians who would love to have vehicles, if the price is affordable.

The quantity of world oil pumped is now constrained--that is, no matter how much we pump, it has to be divided among those who want it. Supply doesn't increase by much, regardless of demand. If we decide not to use oil, world consumption will remain pretty much unchanged, because someone else will use the oil. (This is not true for coal and gas, because their production is not constrained.) Economic models don't consider this case, so the usual assumption is whatever we cut back, will save world consumption by the same amount. Definitely not true!

See my post Climate Change: The Standard Fixes Don't Work.

Oil Demand is getting hihger and higher day by day, due to which prices also getting increase...

PHP developers for hire

"The risk, as I see it, is that the price consumers can afford to pay will drop below the cost of extraction."

- this is a more complicated issue than it seems at first. For one, the opposite can also happen, the cost of extraction may rise above what consumers can pay, with similar results. The issue of how large is the "slab" of oil extractable at today's costs is still not clear, even if Euan recently said it's a large slab. Also, the cost of extraction is far from uniform, so production from different oil fields will be affected differently. Moreover, since the price is set by the cost of the marginal barrel, producers with lower costs (for now) are currently reaping a lot of profit - which many of them use to keep their populations from revolting. Interesting scenarios ahead.

Back to the issue of "the price consumers can afford to pay". That too is complicated. Consumers differ, in both affluence and lifestyle and efficiency of oil use. Watch the poorer Chinese outbid the affluent Americans. How? By deriving more utility from the smaller amounts of oil (per capita) that they use. But even in the USA as oil consumption is curtailed by higher prices, the remaining usage is of higher utility. E.g., one may reduce "pleasure" driving but keep on commuting to work. Or switch to a smaller car. Although there are limits to the price of oil, based on affordability, this price limit is therefore rising over time.

A related issue is that even if the price consumers can afford stays the same, the price of extraction may rise above what consumers can afford to pay.

I would argue that government of oil exporters have gotten used to the extra money that they get from the very high taxes that companies pay on oil that is extracted. Even if the cost of extraction isn't high, the economies are by now set up in such a way that they are dependent on the full price they are getting. This is reflected in the Fiscal Costs of OPEC that Matt talked about.

This article is enormously unrealistic.

Oil just isn't that essential: if the prices rises too much, freight can move to rail, then electric rail; personal transport can move to mass transit, carpooling, natural gas or hybrid electrics, then to PHEVs, then to EVs and rail; space heating can go to heat pumps; the *small* percentage of remaining applications can go to synthetic fuel and biofuel.

Germany, for example, has relatively few people who can't afford oil - it's more a matter of choosing not to use it because something else is a better value. Another example: the average Prius buyer in the US is more affluent than average: they buy something more efficient because they want to, not because they have to.

Oil doesn't become unaffordable at a certain price, it just becomes overpriced compared to the (often better) alternatives.

----------------------

Wind and solar will do. Nuclear will get used as well, though at this point I think wind and solar are cheaper and faster (and safer) in OECD countries.

Electricity will be used for HVAC, and almost all passenger and freight transportation. Synthetic fuel (from seawater and renewable electricity) and biofuel would supply relative small niches: aviation, some long distance land and water transportation/shipping, seasonal agricultural work, petrochemical feedstock. Greater efficiency will be important (PassivHaus, etc).

All in all, this is likely to be about the same cost as our current system, and much cheaper when you add in external costs like pollution and supply security.High oil prices cause recession.

Nick, you always skip the part where we actually transition to alternatives. The enormous percentage of people who rely on oil, in some fashion, to earn their incomes won't wave a magic wand and suddenly find employment is sectors that "oil just isn't that essential" to. Many of these folks don't have much wiggle room when it comes to change. I suppose we'll just push these folks out the back of the bus. What you describe as an orderly transition will essentially be a system of triage, one we're already seeing.

"Wind and solar will do. Nuclear will get used as well, though at this point I think wind and solar are cheaper and faster (and safer) in OECD countries."

How do you transition a huge metroplex like Atlanta or Dallas, totally invested in and reliant on a petroleum-based transportation system to an electrically based system of moving people and goods? I suggest you pull Atlanta up on Google maps and 'drive around' a while.

The enormous percentage of people who rely on oil, in some fashion, to earn their incomes

Who do you have in mind? Employment in the oil & gas industry isn't going to shrink soon. I agree at some point they may face some pain - of course, that's nothing new. Look at what happened in the 1980's as the industry shrank.

Other industries will do just fine. The car industry is gradually going to hybrids, then PHEVs, then EREVs, and probably eventually pure EVs. Shippers will go to rail.

ICE engineers will be in trouble. Truckers and coalminers will be in trouble. Investors in FF industries will lose money. There will be some people hurt by the transition. Of course, that's always been true of transitions. Ideally, as a society, we'd be kinder to such people. But...that's very different from general social stagnation or collapse.

How do you transition a huge metroplex like Atlanta or Dallas

Freight goes to rail. People go to hybrids, PHEVs, EREVs, and EVs. They're affordable, convenient, etc.

Nick, I toss in my vote on your side. I have done all that stuff, admittedly as a hobby and amusement, not for any economics reason, but it works and makes me feel I have done good for my grandchildren's future. A couple of days ago, I flipped the heat button for the first time on our ductless mini heat pump, running on PV, and got some nice warmth on a chilly evening - (in August? Here?, Hey, where is that global warming?).

Solar is gonna murder ff, and I will have fun at the funeral party.

Yeah!

Solar is gonna murder ff

I'm having fun watching solar grow so quickly. I like to look at the California ISO website, and see how nicely the wind and sun play together!

Seriously? What are you going to use for cooking in the evening, and heating during winter? Given that the US uses more AC then the rest of the world combined, and most of the cooking and heating is done by gas I can see why you assume that peak electricity demand is on hot sunny days. However take out the gas, and you have a massive demand to fill in the evening, especially in the winter as people come home and want to cook some dinner, turn on the electric blanket, heat up the house, and lets not forget charge up the electric vehicle ready for the commute to work in the morning.

I like to look at the ISO website and see how funny it is when you get a lot of wind on a sunny day. California has a lot of coastline, so it's likely to be more favourable to wind then many areas. I'm not sure why you assume there wont be dull, still days in winter?

What are you going to use for cooking in the evening, and heating during winter?

Mostly windpower. Some hydro, geothermal, wave, tide, biomass. And, heck, nuclear, probably.

I like to look at the California ISO website and see how funny it is when you get a lot of wind on a sunny day.

I do too - it's marvelous how well wind and solar complement each other. Wind dips in the middle of the day, and solar fills that dip perfectly.

why you assume there wont be dull, still days in winter?

There will be a few, though not as many as one might think. We're likely to import power from our neighbors (where the wind is blowing), burn a little biomass, put off some EV charging, iron smelting and clothes washing until later, and pull hydrogen and methane from underground storage (where it was placed earlier, using surplus wind and solar power).

I assume you yourself are living off grid, and not using coal, oil or gas?

No, I don't think being off grid is a great idea. I do live in a highly walkable area, take an electric train to work, and the house is insulated so that heat isn't needed above freezing.

Really, the more important thing is collective action.

Have you given money to your representatives, and told them you want them to do something about climate change?

"Have you given money to your representatives, and told them you want them to do something about climate change?"

Yes, I have. Instead of fighting for CO2 reductions, he decided to not seek reelection and took a job as a lobbyist for Duke Energy. From Wikipedia:

If you can't beat'em, join'em. After all, they pay better. Our new Republican rep. has twice refused to take my questions on CO2 reductions and campaign finance reform.

Perhaps your question was tongue-in-cheek?

The odd thing is that congress-critters, and other officials, are remarkably cheap to buy! Average campaign spending is less than $5 per constituent.

We can afford to buy them back, if we want to.

While I don't agree with everything that Nick has said, overall I think that he is right. Higher oil prices have a great way of changing the economics of how the world works. Sure, it does not happen overnight, but if provided some time, it happens.

If you look at the figure entitled World Oil Consumption, you can see that US, EU and Japan oil consumption has been dropping. But if you compare where we are in 2013 to where we were headed if we would have continued on the path that we are on, since 2004 the oil consumption of the US, EU and Japan is down about 21% from the projected demand in 2013. That is huge (more than 2% per year)!!! There clearly is a lot of substitution going on to make that happen (the recent very bad recession likely has played a role in that as well).

Keep in mind that Europeans pay over $7 a gallon for gasoline, and their per-capita oil consumption is half that of the US. While Europe is in recession now, they were not before the great recession and they were still papying a lot for fuel (although the high price was due to taxes which eliminates the need for people to pay for things like health care separately).

Clearly, there will have to be a lot of changes to our society for us to move away from crude oil. If we can stay on a plateau for a while (or at least not suffer a steep decline) as crude oil prices continue to increase, I think that we can have an orderly transition away from crude oil.

Europeans pay over $7 a gallon for gasoline, and their per-capita oil consumption is half that of the US.

Their per capita oil consumption for personal transportation is only 18% - high oil prices work to reduce consumption! Europe's oil problem is freight hauling - they need to rationalize their Balkanized rail system, tax personal transportation diesel as much as they tax gasoline, and tax industrial/commercial freight diesel as much as personal transportation diesel.

I just don't think you and Nick are thinking systemically; it's a big picture thing. US national debt just went over $16.902 trillion. The US and EU have been hanging on massive injections of fiat capital. Consumption has, indeed, dropped; consumption millions of folks rely on to pay their bills. A huge part of our economy depends upon discretionary spending that fewer people can afford. Feedbacks and knock-on effects. U-6 unemployment is still over 16%, and services are being curtailed at the state and local levels (North Carolina's new Republican majority just slashed educational funding dramatically). I could go on, but all of this adds up to a slow wearing away at our economy's ability to support growth, which means many debts won't be repaid, lost tax revenues, rising relative costs for essential goods and services, deflation in things that don't matter as much, infrastructure falling farther into disrepair.

Too many claims on too few real resources, and it's global.

don't think you and Nick are thinking systemically

We really are.

consumption millions of folks rely on to pay their bills.

I'm not sure what you mean. More efficient cars don't put anyone out of work. Replacing fuel oil heating with heat pumps doesn't put anyone out of work. KSA is doing ok.

discretionary spending that fewer people can afford.

It may feel that way, but discretionary spending is actually up. I agree that spending is shifting to the rich, but that's a different problem.

services are being curtailed at the state and local levels

That's because Republicans, controlled in part by wealthy FF investors who don't like democratic governments that might help us transition away from them, are cutting taxes. There's plenty of money for taxes out there, we're just not collecting it!

Again: Too many claims on too few real resources. We won't be able to afford the changes you envision at the scale required. We'll be to busy trying to survive the damages done to date.

" More efficient cars don't put anyone out of work."

Yes, they do, especially at the scale you imagine.

"It may feel that way, but discretionary spending is actually up.

CNN/Money, today: Wal-Mart warns of 'challenging' economy

.

Macys reporting the same thing. Snapshots, all..., but fewer sales means fewer employee hours, meaning folks have less to spend at Walmart.

"I agree that spending is shifting to the rich, but that's a different problem."

There is no 'different problem'. They're all part of the paradigm (predicament) of overshoot.

Probably best not to reply to him Ghung.

Gail ignores him. He attacks her at every opportunity as she refutes everything he denies.

For the last six years he's been saying things are getting better and we need to "just buy a Prius".

Gail ignores him.

Sometimes she replies, but oddly enough, she really doesn't deal with the substance of the criticism.

Either way, she doesn't seems to process the arguments.

she refutes everything he denies.

No, she really doesn't. She makes arguments that don't really make sense, and doesn't provide any evidence at all.

For the last six years he's been saying things are getting better and we need to "just buy a Prius".

And, in fact, they are getting better, though not nearly as fast as we'd like (to be clear, I don't think GHG emissions are improving the way we need them to).

Gail's solution seems to be "drill, baby, drill".

Frankly, this is exactly the problem that killed TOD - the inability of posters and commenters to take in new information and evolve their ideas.

Jeez... Well Gail got one thing right-

Stumbling Blocks to Figuring Out the Real Oil Limits Story.

Ask yourself: what's Gail's prescription?

She's argued against wind and solar. She argues that only fossil fuels will support civilization.

If you were Exxon/Mobil, would you like her approach?

If you were an advocate of attacking Climate Change, and reducing GHG emissions, would you like her approach??

"Ask yourself: what's Gail's prescription?

I'm not expecting Gail to offer prescriptions. She's an actuary; her job is to describe risks as she sees them. If I hired her to advise me on a course of action, hopefully she would tell me to do what I've been doing:

- Reduce dependence on complex systems

- Develop social capital in a place that has a reasonable chance that social capital can be developed and maintained.

- Develop the skills needed for self-reliance and sellable skills

- Maintain situational awareness

- Pray for the best, plan for the worst, keep one's expectations in check, make one's self as comfortable as possible, and hold on to one's ass.

If her recommendation doesn't include all of the above, she's fired.

She's an actuary; her job is to describe risks as she sees them.

If there's anything an actuary should do, it's rely on quantitative, concrete evidence.

Do you see any evidence in this Post? Anything beyond pure speculation, based on personal intuition? Yes, the author's intuition matches with yours, but still...where's the professional evidence?

Nick,

Pot, kettle, black.

Whenever you are challanged to show some numbers on how we can get to your utopian world, you link references to peoples beliefs in the main, with some made up numbers thrown in (theirs), that happen to coincide with your belief.

You NEVER come up with the indepth numbers of how much energy will it really cost to get to the utopian future, simply because it shows that it is way beyond the budget of possible to get 7 billion of us there.

A small example of your ignorance to reality is highlighted by the "trucks to trains" for freight, which completely disregards the current configuration of most urban layouts. Trying to come up with a figure and timeframe just for this would show the impossibility of the task with so little time and resources to do so.

Who misses out??

Making up numbers

Well, you must not be reading my stuff over the years. Lately, of course, I've been providing fewer links, due to the moderation problem.

For data, just go to wikipedia, or google this stuff. Heck, go to my blog - google Nick's energy faq. It's easy enough to see that US and world GDP are growing; that wind and solar are growing fast; that hybrids can be bought for less money than the average new car; etc., etc. etc.

For numbers on how to get there: it's pretty straightforward. Windpower, for instance, costs about $2 per peak watt, including all costs (and falling). To provide 50% of US generation (very roughly to replace coal) would require about 220GW, or about 700GW at 30% capacity factor. That's $1.4T, or about 2/3 of one Iraq War. Over 20 years, that's $70B per year - chump change.

To power an EV with wind: the average US car drives 30 miles per day. At 300Whrs per mile, that's about 10 kWhrs per day. At 30% capacity factor, you'd need about 1kWh of wind turbine capacity to power it: that's about $2k to power an EV. For 25 years! That's incredibly cheap.

Yes, most cities have dismantled the feeder lines that would take freight into urban cores. The simple answer to that is EV trucks, with short range. Intermodal containers could be shifted from freight trains to trucks easily. Heck, that's how most freight moves in the US already.

Hi Nick. We've been down this taxpayer-funded road before.

There are many reasons why individuals and families may or may not be able to afford to buy an EV or hybrid, but the massive infrastructure invested over the last lifetime to support private personal transport could well start to crumble in earnest when the economy rolls over and tax revenue falls.

I agree that some people will purchase EVs, and small E-trucks would be very handy for contractors, but my sense is the entire fleet of private cars in North America won't be converted anytime soon, if at all, and that more and more people will decide to just give up car ownership all together when they choose to live in more urban locations with more affordable transport options, like transit, bikes and shoe leather. Personal transport takes a larger chunk out of a family's disposable income the further one has to travel in their daily routine, and the more cars they possess.

Why should cities continue to subsidize EVs and hybrids to the same unsustainable extent as gasoline-powered cars with freeways and overscaled suburban cul-de-sacs? Why should cities also continue to devote a third to half of their precious land to asphalt? Why should we continue on the road of excessive energy waste by transporting predominantly a single human being in each vehcle, E-powered or not? Why should we continue the practice of building (or maintaining) distant car-dependent and highly-subsidized subdivisions and condemn people to drive 4 km in their EV just to get a loaf of bread?

Well, I like dense urban living. I take an electric train to work everyday.

But, of course, "drive until you qualify" is alive and well. Housing costs are far more important than the cost of fuel (or electricity) for commuting.

And I like sparse rural living in a county with a population of 10,000. How can this be, that someone doesn’t value magnificent urban living surrounded by high tech gadgets and entertainment? Maybe everyone doesn’t share your values Nick?

Well, that means you're not from Chicago...

Seriously, you're making a point similar to one I made elsewhere in the comments - that dense urban living is great, but most people can't afford it. So, most people won't use rail for most things. They'll use hybrids, phevs, EV, etc.

No, Nick, I think urban living sucks big time. I bought a small farm in south central Illinois 8 years ago after having lived in large metropolitan areas for 52 years. I don’t miss the crowding, expense, pollution, crime, traffic, and the obnoxious people I’m forced to deal with on a daily basis. The food was great, but I can duplicate that in my humble country kitchen.

Well, that's great for you. I personally find farm living isolated (fewer people, less diverse, far away), far from medical care, impoverished (perhaps you're retired), dangerous (especially if you're a farm worker, or have to drive a lot) and...boring. But if a farm is what "gets your motor going", that's great.

I was answering "Salish Sea"'s question about mass transit vs cars. Did you see it, above?

To each their own. Although I see fewer people as a good thing, especially if these are people I know, trust, and could count on in a crisis. Impoverished? Only if you measure your life in “stuff”. Dangerous? Compared to the city, which I know very well, and have worked in bad areas and have been shot at, it’s not even close. Just look at the violent crime rates. Hell, I don’t think there has been a murder in my town since anyone can remember. As far as driving, I can get to anywhere a lot quicker than I could in Chicago – with no traffic to boot at speeds which allow a high mpg.. I will concede medical care. But why is that? Our magnificent free market system for medicine results in doctors going where the bucks are. Of course, it is much less likely I’ll suffer from a respiratory disease (I can see the milky way from my porch on a clear night), gunshot wound, or assault. Yeah I hear the boring part, usually from people who spend much of their leisure time and money in bars, clubs, concerts, etc., etc.,. Again, to each their own. I’ll take mine country. To da loo, got to check my pear trees – they’re loaded, and feed some of the dropped apples to the hog.

Ahh, here we go, more of the same. No real numbers. Just glib soundbites of off the cuff numbers that not only have no meaning, but really do say more about the author than anything else.

Fancy wordsmith sleight of hand tricks that would make a magician proud, some examples.......

I say...

" it is way beyond the budget of possible to get 7 billion of us there."

Nick's response....

Last time I looked the USA had a population of ~315m, or about 4.5% of the worlds population. Dismissing 95% of the worlds population doesn't cut it, unless you really are agreeing about a doomerish future after all.

I state....

"trucks to trains" for freight, which completely disregards the current configuration of most urban layouts. Trying to come up with a figure and timeframe just for this would show the impossibility of the task with so little time and resources to do so".

Nick's comeback....

and

Again a lovely sleight of hand. The question never mentioned anything about small EV vehicles, it was about the poor layout of current cities for freight to move to trains. The answer about electric trucks, seems to include the small power cost of something completely different.

In Nick's future cornucopia, the cost of building all these extra wind turbines on a massive scale worldwide will cost $2/w, yet the wind energy bodies themselves in their own reports already acknowledge the following....

Clearly in an energy constrained future when we are on the backslope of oil production, the commodities needed to build all these wind turbines and towers are going to push the cost UP greatly. Of course all the best sites get used first. These have a combination of great consistent wind resource, good roads for access and high voltage transmission lines. Having to add distance to existing roads and grid infrastructure is not included in the capital cost. Of course this number will grow as poorer and poorer sites have to be utilised. Again higher real costs than the off the cuff number given.

Thank you Nick for proving my point precisely, you really don't understand the numbers nor the problems.

Dismissing 95% of the worlds population doesn't cut it

The basic point is that windpower is very affordable - just as affordable as fossil fuel. I agree: some places in the world have a hard time affording anything at all. But, renewables will work better for them than FF. For instance, solar is far cheaper than kerosene: many people in Africa are having their lives improved by solar lighting.

The question never mentioned anything about small EV vehicles, it was about the poor layout of current cities for freight to move to trains.

And, electric trucks are the straightforward answer for moving freight from trains to local stores. I don't understand your objection.

Atlanta, for instance, is well served by freight trains, but the local feeder lines have been paved over. Electric trucks would fill the gap.

Rising commodity prices during the period 2006-2008 drove increased wind power costs

Notice that period ended 5 years ago. Windpower costs have fallen since then. The period you mention was part of a commodity bubble, partly caused by China. Rising steel, copper and concrete costs will not be a barrier to building wind turbines.

all the best sites get used first.

Not really. Very often the easiest sites go first, and that can mean closest to existing generation, or located in areas with good political support. There's easily a terawatt (average) of high quality wind resource available - we're nowhere close to that.

Having to add distance to existing roads and grid infrastructure is not included in the capital cost.

The $2/Wp includes all costs, including access roads and connection transmission. That cost, by the way, continues to fall.

Finally, if you want lots of concrete examples and numbers, try my website: google Nick's energy faq.

I don't think thats correct. Simplifying I think her position over the years has been that cheap energy underpins the economic and financial status quo and without it there is a bit of an issue in the de-leveraging domain. Not that large complex societies are a bust without oil. Maybe this one is thou

As for the people not evolving their ideas...well you may have a point there but perhaps you run foul of this crime as well?

I think it's accurate to say that Gail is arguing that without oil, advanced civilization is impossible.

This is highly unrealistic. Heck, look what the US built up until around WWI, when oil was insignificant. If oil had never arrived, economic growth certainly would have continued. Heck, growth was faster in the 1800s with coal than it was in the 1900s with oil.

As for my ideas: they've evolved quite a bit. When the Club of Rome's Limits to Growth came out, I was quite alarmed. Over several decades of personal and professional involvement with energy stuff, I changed my ideas: I'm not worried very much about LTG, but I am very worried about Climate Change and other things that I would call "environmental vandalism" (species extinction, etc).

There is a reason for the tempo of growth since 1750, in that it solved some very basic problems and issues that humans have faced since the dawn of history. But those solutions are non-repeatable, therefore growth would not continue the same, and in fact, even with all the cheap (almost free) energy from oil, it hasn't continued the same, but slowed down drastically. Robert J. Gordon explains it very well in his article Is U.S. Economic Growth Over? Faltering Innovation Confronts the Six Headwinds (google it).

Gordon has some good points. And, I agree, as time goes by economic growth is likely to slow down, especially in hard goods. I'd say Gordon's arguments are compatible with what I've been saying, although kind've "orthogonal".

You could argue that growth has gotten harder to achieve, but the flip side of that is that growth is needed less than it was before - the marginal benefit is decreasing, as we get a larger percentage of our needs filled.

Anyway, I think you'd be hard pressed to argue that the advent of oil suddenly "goosed" the economic growth engine.

If you are not worried about limits to growth, does that mean you don't accept that there are limits to growth? On a spherical planet, or on a flat earth?

No, it means that I expect growth in commodity consumption to stop all by itself, as people get enough "stuff", long before we fall off the edge of the planet(!).

It's already happened in the US and Europe: people have enough cars, enough washer/dryers, enough homes, etc, etc. E.g., car sales plateaued 40 years ago, and young people aren't all that interested in cars - iPhones are better for schmoozing, no need for Saturday night cruizing...

Obviously you have no connection with the real world where billions are starving, and would like to own an iCrap, rather then working in a sweatshop where foxconn have installed all manner of devices to stop them killing themselves.

The EU, US have not stopped consuming stuff. Even if the rate of goods consumed has levelled off, something I doubt, that doesn't mean people have enough stuff. They are still buying stuff, consuming resources. Clearly you think resources can continue to be consumed at a constant rate, and the pollution will 'go away'. Something that can't happen on a spherical planet, so it must be on a flat earth that goes on forever.

Those billions, of course, are not in the US or Europe.

A constant level of "consumption" of cars, for instance, requires a renewable energy input and recycling - 99% of US scrapped cars are recycled.

Well, hooray for us, and bad luck for them, eh, Nick? Got anything in your house made by those unlucky unfortunates?

No, my point is that there's enough resources for them, too.

Currently around 900million cars in the world. If there are enough resources for everyone, then to bring them all up to the same standard we only need to build another 4.1Billion cars.

Hhmm. What's the French ratio of cars per capita?

What? Do housing prices reflect the fact that there are "enough homes"? If there was enough, housing prices would plummet, when in fact the opposite is true.

Have you read that 60% of the buyers of homes in 2013 came from the all-cash crowd. This is not what you would expect if everyday workers are buying the houses on the market.

Wealthy investors are definitely doing better than the average worker. But what does that tell us about energy?

If oil costs were really forcing companies to lay off everyday workers, those companies would be shrinking. But, they're not, overall.

???

Housing prices did plummet, right? Many are still standing empty...

You were talking about US and Europe. I guess your perspective is completely screwed up by what is written in the media constantly about Ireland, Spain and Greece, but the truth is that in Germany, Netherlands, Austria, nordic countries, and most of the rest of the countries... housing prices did not plummet at all, and nobody would say that there is "enough houses".

There's a generally recognized housing shortage in Germany, and those other countries? Do local regulations prevent construction, and create an artificial shortage?

Eurostat is great:

http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/statistics_explained/index.php?title=Fi...

prices in aggregate have not plummeted but

spain: http://www.ine.es/jaxiBD/tabla.do

Holland:

http://statline.cbs.nl/StatWeb/publication/?DM=SLEN&PA=71533ENG

Things look a bit different.

It's important to keep in mind how indexes / aggregates are constructed - issues like weighting and inflation/deflation. Different indexing choices can lead to dramatically different results. Weighing by $ of transactions, population, working population, quantity of housing stock housing stock, square footage can will give you different indexes. Add to that the difference in income/housing ratios and you can pretty much create any result you want.

Rgds

WP

The historical highest rate of GDP growth of the USA was during ww2 under a command economy. Not sure what you mean about the coal vs oil age lead up to ww1?

and the fact you use a time when oil was insignificant sort of works against your general position?.

the thing is this you are constantly arguing against oil primacy with arguments that seem to support it. It is probably the result of internet quick fire posting by all concerned and we end up talking across each other.

what is your basic position

one seems to be oil has no significant innate primacy and can be replaced via some sort of price mechanism? yes?

Here's the stats for the idea that our civilization is not dependent on cheap energy, or on oil:

US growth was faster before 1945, using moderately expensive, non-oil energy:

1800-1900: 4.13%

1900-1945: 3.53%

1945-2000: 3.17%

More stats:

US 1913

oil only 10% as large as coal:

oil: 1.4 quads (681k bpd @5.8Mbtus/b)

coal 14.6 quads (560M tons/yr @26Mbtus/ton)

US 1900

oil only 5% as large as coal:

oil: .4 quads (174k bpd @5.8Mbtus/b)

coal 7.2 quads (275M tons/yr @26Mbtus/ton)

the fact you use a time when oil was insignificant sort of works against your general position?.

I'm not sure what you mean. My point is that oil isn't essential to modern civilization. We didn't have it before 1900 (as a practical matter), and we won't need it in the future. Yes, oil has no significant innate primacy and can be replaced via some sort of price mechanism. Or, heck, it could be pushed out by regulation, like CAFE standards and CO2 reduction requirements.

At one point in time I feared that after the oil production peak, civilization would be doomed (I guess it is a shock to learn that, isn't it??). However, after I had to think through this for quite a while while hearing different points of views, I no longer think that way. That does not mean that I am completely confident that there will not be a melt down.

One person who has really opened up my eyes to the possbility for using much less petroleum here in the US and doing so without economic chaos is Amory Lovins of the Rocky Mountain Institute - one of the greatest thinkers and engineers/analysts of our time. Amory has estimated that we can achieve something like more than 80% reduction in petroleum consumption in this country. He does not just casually say that, but he wrote a book called Reinventing Fire in which he lays out the means for getting there.

On the other hand, there are plenty of examples of doomers on the Oil Drum who can't seem to let their minds see the possibility for greatly reducing our petroluem consumption. In the end, they may be right. But the 21% reduction in oil consumption in the developing countries (US, EU and Japan) since 2004 seems to be proving them wrong, and proving folks like Amory Lovins to be correct.

Just so that you know, my wife and I solely own one car - a Toyota Prius. I ride my bike to work and back year round. We put in a ground-sourced heat pump and reinsulated our house. Eventually, I plan on putting solar panels on our roof. Hey, if I can do this, why not everyone else??? I think I read somewhere that 20% of the newest generation plan on not even owning a car. Things are changing - I think the question is can they change fast enough...

I agree pretty much with all that.

It's worth saying that we really can eliminate oil entirely. I'd say that very roughly 10% of our current liquid fuel consumption would be very difficult to replace, but synthetic fuel (at $5-10/gallon) is entirely feasible with today's tech - some biofuel, but mostly electrolyzing hydrogen from seawater, and combining it with CO2, probably also from seawater (CO2 concentration is much higher in seawater, so it would be cheaper).