Tech Talk - A Dickensian Situation Revisited

Posted by Heading Out on August 31, 2013 - 11:47pm

Back in March 2005, I posted my first offering to the new site that Kyle and I had agreed to call “The Oil Drum.” Now, some eight years later, this will be my final Tech Talk to appear on the site, and it is perhaps appropriate to go back to that first post and make a couple of comments on how it panned out. It read as follows:

When I was young I was fascinated by a small china statuette that my grandparents had of Mr Micawber. He is a character, and a sympathetic one, in Charles Dickens's book "David Copperfield", in the course of which he goes into debt. His explanation of his financial condition can be compared to the coming world experience as we now live through Hubbert's Peak. You might, in today's phraseology, call this the Money quote:

'My other piece of advice, Copperfield,' said Mr. Micawber, 'you know. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen nineteen and six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery. The blossom is blighted, the leaf is withered, the god of day goes down upon the dreary scene, and - and in short you are for ever floored. As I am!'.

In this case, consider that our expenses, i.e. the world use of oil, went up last year to around 83 million barrels every day (mbd). (A barrel is 42 gallons). Now as long as our supplies (income) can match this outlay then we are in happiness. This was, in relative terms, where we ended last year.

However this year our expenses are going to go up. It is a little difficult to predict exactly how much but current predictions are for this to be around 2 mbd. Let us equate this to the old English sixpence (which was back then worth about a dime. Twenty pounds being worth about $100).

If we follow the Micawber example - if our income, world oil supply is equal to or greater than our expenses, then we can stay happy. But here is the rub:

When world oil production is just about as high as it can be (non-OPEC countries are now producing just about as fast as they can) and OPEC spare capacity is down to around an additional 1.3 mbd, then our income this year will likely not be much above 85 mbd, if it gets there. (In a later post I will explain why it probably won't).

So we are at the point where, within the next few months, income and expenditures will be in balance (Micawber's twenty pounds). Except that the industry being a big one there are always things going wrong. In the latter part of last year for example we had:

• the hurricanes in the Gulf that closed down about 0.5 mbd of production for several months

• oil production in Iraq, which should be around 3 mbd, but because of pipeline bombings etc dropped below 2 mbd

• there were frequent threatened strikes on the oil platforms in Nigeria

• and Russian production declined more drastically than had been anticipated

Some of these are still with us, some have been resolved. And other problems, such as the complete employment of the world tanker fleet, have yet to make an impact. But any one can drop supply.

Yet while our supply (income) is about at a peak (twenty pounds), our expenses (demand) are still going up by this sixpence a year. So that some time this year expenses will have gone from twenty pounds to twenty pounds and sixpence. A number of economists had been predicting that there would be a reduction in the rise in demand to keep us below that figure, but it is already clear that they do not adequately recognize the considerable needs in China and India that drive this increase (and they only have to read the papers to see it).

The big question is when will we reach the point that we cross over the balance point? Right now with the Saudi Arabian government saying that they can increase production by up to 1.5 mbd, one might think we could get through to just about the end of this year. Unfortunately, some of us are a little cynical about that number, and I'll explain why in another post.

One final gloomy thought - production in other countries (such as the UK) is falling, and the countries that used that supply must find another source. And if we are now at the peak of production, then our income cannot increase above twenty pounds and and may indeed fall back below twenty pounds, while our expenses will continue to increase to twenty pounds and sixpence. It is not the absolute size of the market that will now drive, but the relatively small fluctuations that take us out of balance.

The result is misery, and we are forever floored.

Looking around it is reasonable to note that we don’t see the level of misery that, from reading that post, one might have expected to happen. We have gone through a major recession, yet demand has, overall, increased and production has risen to meet that demand. Yet looking at how this has been met is instructive.

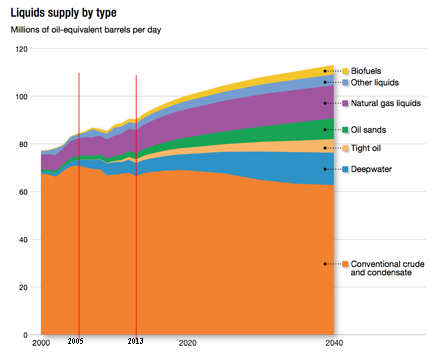

I have added lines to show the situation in 2005, when the piece was written, and for this year. It is worth noting that using the definitions that Exxon Mobil give, conventional crude and condensate production has indeed declined since I wrote those words. And if one includes Oil Sand and Deepwater, then production has remained fairly stable at the levels back in 2005 and will (according to EM) likely stay so into the projected future.

The three sources that I had underestimated in terms of production growth were in Biofuels (which is now at around 2 mbd), the growth in Natural Gas Liquids (which for OPEC alone is now projected to reach 6 mbd by next year up from around 3 mbd in 2005, and the growth in tight oil. This latter development, particularly with the use of long horizontal wells that are artificially fractured and injected with a slick-water suspension of a proppant, has been very successful in developing resources which were otherwise at best marginally economic. However, the relative contribution that this is expected to make in overall supply is not that great, and I expect that, because of the high decline rates in individual wells, that this will only contribute on the margin of the problem.

When I began writing at The Oil Drum I was concerned that there was a lack of understanding of the impact that reservoir decline rates would have on long-term supply. As larger fields are depleted, so the world turns to smaller fields and these drain more rapidly, so that more and more are needed. (The Red Queen situation that Rune Likvern and others have so aptly described.

Deepwater resources have proven to be more difficult to bring on line than originally estimated and thus, for example, in the case of Brazil OPEC now anticipates that the production from the Lula field (originally Tupi) will only offset declines from wells in the rest of the country, with perhaps only a gain of 10 kbd overall from the addition of the 100 kbd expected from wells now coming on line. And thus, while this is a resource getting more attention (there are expected to be 60 Deepwater rigs in the Gulf of Mexico by 2015) the slow pace of development may not fill the increasing gap left as conventional oil production continues to fall, as Exxon Mobil suggest.

In retrospect, therefore, I was wrong in anticipating a relatively immediate impact from an anticipated imbalance between oil supply and demand. But, within the time frame, the price of oil has risen and the future looks no happier than it did back in 2005. The threats have changed – we seem to be in a quiescent period for major Gulf Hurricanes, for e.g. – but the threat of growing and spreading turmoil in MENA makes it less certain that we can count on much increase in production from Iraq, among others. Russian production rebounded more than I expected, but whether that can be sustained is still in doubt. The hope at the beginning was that the threat would spur increased looks into alternate sources of liquid fuel. But while there was a flurry of activity into biofuels, (and I myself saw algal work that held a great potential, though funding has now disappeared for that effort) there is less of a feeling of urgency in the air. Wind and solar sources have reached a point where they are no longer novel, and there is not much else in the near term that holds much potential.

Oil production takes money and resources, but most critically, it takes time. Without that investment, particularly in viable alternatives, the oil “income” (supply) will likely soon start to fall short of the oil “expenses” (demand) and as Mr. Micawber so aptly said “we are forever floored.”

When these posts began, technical blogs such as TOD posed the potential for mass education in a way that had not been seen before. Readers have been kind in regard to the quality of the posts themselves. But the contributions from those interested, and those in industry who took the time to comment and debate, ended up making this much stronger than the initial words in any post. Expertise came in many forms and informed me as well as the rest of the readers in what turned into a wonderful opportunity for many people to understand some of the complexities of supplying the world with hydrocarbon energy. I was thus able to help bring a little understanding of the energy business to vastly more folk than I had in the entirety of my academic career.

I will always be grateful to Kyle for giving me the opportunity to make this contribution, and to his efforts which led to its great success. I can illustrate that with some numbers – as an academic I took persuasion to allow my class size to rise much above 20, and at Bit Tooth Energy I see about 300 readers on a typical good day – Kyle had us above that number in a very few months, and at its peak TOD was handling 200 times that number. The site would not have continued too long as it grew in size without the indefatigable SuperG, who kept the site up under wide ranging pressures, and took care of the technical side of the house. Leanan brought in and kept us readers, and provided many of the topics that we needed to create the posts on site, and Gail kept me going with encouragement and support in more difficult times. Nate orchestrated the closing posts and that was not easy.

The folks Kyle brought in to build an international forum were formidable and highly productive, and so to them, and to all of the gentle readership I say again a heartfelt “Thank You!”

(Heading Out – Dave Summers in the mundane world – will continue to write Tech Talks at Bit Tooth Energy, though he writes on a wider range of topics at that site).

I want to thank all those who contributed to the Oil Drum, both contributors and commenters. I started my own blog about a year before the Oil Drum and one of my first posts was on Peak Oil. I have been a regular reader of the Oil Drum from the very beginning. When I recognized the considerable expertise at this site I decided to stick to something I knew about - politics. Any Peak Oil related posts did little but point my readers to this site. I have visited the Oil Drum at least once a day from the very beginning and I am a wiser person because of that. Thanks to all who have contributed and commented.

Ron Beasley

The hope, at the beginning, was that the threat would spur increased looks into alternate sources of liquid fuel.

It would be interesting to make a quantitative estimate of how much liquid fuel we "really need". It might include such things as aviation, long distance water shipping and seasonal agriculture. We'd take into account substitutes and potential efficiency gains. We might want to assume that oil was properly priced (say, at $2/litre, to internalize pollution and security costs) for all consumers (which would be a change for industrial/commercial in Europe, and pretty much all consumers in other countries).

Perhaps 10M bpd?

How long could we easily produce that much? How difficult would it be to synthesize that amount? What's the likely cost of synthetic fuel? The likely maximum cost of synthetic fuel is roughly $2.50/litre: synthesized with renewable power, using electrolysis and carbon capture from the environment (10kWh/litre / 33% efficiency x $.08/kWh for I/C electricity). How large a burden would producing 10M bpd of synthetic fuel be?

I am using about 42 gallons of gasoline/year which is refined from about 2.2 barrels of crude oil/year. Of course this does not include embodied energy in things I purchase, but for some sense of scale, multiplying that by 7 billion people yields 42 Mb/d. To get to your estimate of 10 Mb/d, I would need to consume less than 10 gallons of gasoline per year.

Aviation is not necessary and can be removed from the "really need" category. Affordable housing is a necessity but does not exist in U.S. cities where there are jobs. You have got to get from here to there.

That's a good point, though really 42 gallons of gas doesn't count the other fractions (which are pretty fungible), and gas is less dense than oil, so 42 gallons of gas is maybe 6.3B barrels per year, or 17M bpd.

Affordable housing doesn't require liquid fuel, and with good passive-house design, it could be a net energy producer.

If you remove aviation, you really don't need much liquid fuel - you certainly get well below 10M bpd. What do you use fuel for?

I use about as much fuel as you do – I could replace the car with an EV, but I couldn't justify the $ or FF investment. Someday.

At the end of the day, you don't need oil, or other fossil fuels.

I am extremely grateful you put together TOD. It has added dimensions to my thinking which were lacking, certainly in terms of facts but also in terms of point of view.

The quote you start with is one about an income statement but peak oil is about asset depletion (a balance sheet phenomena). Two very different things.

And/but why are you shutting TOD - it seems to make no sense, nor do the explanations which have been offered - certainly at this point when "things" are just heating up?

With regret, willing and able to contribute,

WP

Micawber's other recurring phrase was 'something will turn up'. When I ask people how they will afford a 60 km each way car commute with expensive fuel they reply 'they'll think of something'. The Micawber philosophy lives on. The other throwback to the Dickens era is our apparent inability to wean ourselves off coal. Nowadays the soot and grime is around Shanghai not 19th century London. Events and attitudes remain the same just the setting changes.

Thank you for all that you have done and for all you have given us here at TOD.

It integrates over time and however small the speed is the direction is set.

Thank you! And, for the security of reference accessibility alone, I'll continue to donate. Salutations to the future reading and volley at other sites and blogs. Gus

I have been researching, in some detail, the efforts of France and Denmark to get off fossil fuels, and their success to date. From 2007 to 2012, Danish per capita carbon emissions dropped by -26.5%, French (from a lower base due to 75% nuke, 10% hydro electrical grid) carbon emissions dropped -14.8% in the same five years.

Both nations have comprehensive programs to get off fossil fuels, including oil. In the case of France, coal is just 4% to 5% of their energy supply, so reducing fossil fuels reduces mainly oil & natural gas consumption.

France is in the midst of building 1,500 km of tram lines in almost every town of 100,000 & larger, and some smaller. Copenhagen plans to have bikes modal share at 50% in 2015, and single occupancy vehicles less than 10%. My blog is full of French examples. http://oilfreetransport.blogspot.com

One article I submitted to the editors of The Oil Drum (no response) was about the announcement last March that Paris will double their Metro by 2030 (+2 million new daily Metro riders + 400,000 new commuter rail riders + unspecified new tram riders)

http://oilfreetransport.blogspot.com/2012/07/a-revolution-in-paris.html

Last week, the Danish government produced a list of 72 potential measures to reduce carbon emissions by 2030 in buildings, agriculture and transportation. They are now "picking & choosing" from this list.

I have worked with one of the original designers of the Washington DC Metro system to making detailed plans to triple urban rail passengers miles in the DC area - while reducing the operating subsidy (i.e the additions operate at a marginal profit).

http://oilfreedc.blogspot.com

But none of these efforts to reduce our energy expenditures while improving the quality of life appeals to the editors of The Oil Drum.

So I deeply mourn the destruction of the TOD community. Less so the editorial board.

Best Hopes for the Future,

Alan

Alan,

Any thoughts about the Vancouver Skytrain? Do you think the driverless approach is something that should be imitated?

For very high frequency on dedicated rails (no trespassers) - YES !

As generic cost savings - not so much.

Alan

Do you think it would make sense as a retrofit on systems like NYC, Chicago or Boston?

On the highest volume lines, yes (unless there are technical details I am unaware of). I have a picture of Paris RER Ligne A (~1 million pax/day !) with a train leaving the platform as another arrives behind it. 90 second headways are much easier to do with automation (although Moscow does it manually).

Lexington Avenue in NYC would be my #1 choice (600 K/day).

Alan

Thank you for all your time and hard work. I am grateful for the information.

Dave, great cautionary tale about predictions. But there is one fallacy that seems difficult to correct - the contribution of biofuels is an illusion. Your figure 1 shows a small contribution to world fuel supplies, but numerous posts have revealed that it takes about as much energy to produce biofuels as is recovered from burning them. As a result, biofuels are counted twice; once as the ethanol or biodiesel at the pump, and again as the fossil fuel required to produce that fuel in the first place. Gail among others has shown that the EROEI must be higher than biofuels offer to be viable. Currently biofuels survive only because of subsidies. Brazilian cane ethanol may be an exception, but the calculations omit some externalities.

The situation reminds me of the persistent assertion that the female preying mantis eats the male following copulation. If he isn't tethered, though, he simply walks away.

I'll miss the oil drum.

Consider the energy inputs to corn ethanol production:

1. sunlight

2. natural gas to make ammonium nitrate

3. diesel to transport the fertilizer, corn and ethanol

4. natural gas to power the processing plant

5. coal, natural gas, renewable sources to generate the electricity used by the processing plant and fuel pumps.

Only the fraction of diesel used double counts what is shown in the chart. Ethanol production mostly converts natural gas, which is not present in the chart, into a liquid transportation fuel.

Yeah, what counts is liquid fuel return on liquid fuel invested.

Not so fast. Ethanol production might be seen as a way to produce a liquid fuel from coal (a solid) or natural gas, neither of which is a good substitute for the liquid fuels we now enjoy. Coal-to-methanol would work from a technical perspective, but methanol is rather toxic and tends to destroy plastic components in the fuel system. Then too, electric cars can provide the service presently provided by gasoline vehicles where the daily distance traveled is not too great. That energy in one form may be used to substitute for another makes ERoEI an important metric, though it is difficult to calculate with accuracy...

E. Swanson

Well, I think what you're saying is that we should care about the overall energy consumed.

And, I agree. We don't really have an energy shortage, but we do need to reduce CO2 emissions ASAP. The best thing would be PHEVs or EVs, powered at night (which would encourage windpower, which is hurt by low night time power prices).

I have been researching, in some detail, the efforts of France and Denmark to get off fossil fuels, and their success to date. From 2007 to 2012, Danish per capita carbon emissions dropped by -26.5%, French (from a lower base due to 75% nuke, 10% hydro electrical grid) carbon emissions dropped -14.8% in the same five years.

Both nations have comprehensive programs to get off fossil fuels, including oil. In the case of France, coal is just 4% to 5% of their energy supply, so reducing fossil fuels reduces mainly oil & natural gas consumption.

France is in the midst of building 1,500 km of tram lines in almost every town of 100,000 & larger, and some smaller. Copenhagen plans to have bikes modal share at 50% in 2015, and single occupancy vehicles less than 10%. My blog is full of French examples. Google oilfreetransport. blogspot. com

One article I submitted to the editors of The Oil Drum (no response) was about the announcement last March that Paris will double their Metro by 2030 (+2 million new daily Metro riders + 400,000 new commuter rail riders + unspecified new tram riders)

Google A Revolution in Paris Oilfreetransport

Last week, the Danish government produced a list of 72 potential measures to reduce carbon emissions by 2030 in buildings, agriculture and transportation. They are now "picking & choosing" from this list.

I have worked with one of the original designers of the Washington DC Metro system to making detailed plans to triple urban rail passengers miles in the DC area - while reducing the operating subsidy (i.e the additions operate at a marginal profit).

Google Oil Free DC

But none of these efforts to reduce our energy exepmditures appeals to the editors of The Oil Drum.

So I deeply mourn the destruction of the TOD community. Less so the editorial board.

Best Hopes for the Future,

Alan

France 78% reliant on nuclear, is that your recommendation. So good idea, let the world follow the example of France if "oil free transport" is the road to sustainable population, consumerism, economic growth and the ecological destruction caused by food production.

Most everyone presumes that more building and technology is the way to "reduce". Funny that it has never worked out like that, more is not less, more leads to more it's the human way.

It's never an idea to simply power down, it's "we should use or build such and such" to use less. Taking methadone or smoking e-cigarettes won't cure the addiction, eventually you just have to give it up but preferably before self destruction.

I want to say thank you Dave - for all the work.

I haven't commented much on your articles, since I don't know much about the subject matter, but i have read them all for the past few years, and learned an enormous lot from them.

If this question isn't 'too hot' - pun intended- to handle, I would like to know why a well chosen but exhausted old oil field could not be safely used for the disposal of spent nuclear fuel.

I know that such fields are often under a mile of two of cap rock, and that they are quite stable in the geological sense, having lasted for the many millions of years necessary for oil to form and migrate to the traps from which we pump it.

My thinking is this- that the waste could be finely pulverized, and mixed with chemicals selected to cause the waste to disperse in the rock down there, in a process similar to fracking, and then bond with the rock, so that it could only be recovered, if at all , at enormous expense with the use of a lot of very large and heavy machinery over an extended period of time.

Getting enough of it b back up , if it were distributed among many old wells and highly diluted, to build a bomb would probably be a near impossibility.

Old Farmer:

Thanks for the kind words.

In regard to the injection of radioactive material, to an extent this is practiced today, but they prefer to use fractures generated in imperiable shales as the reservoir, rather than going into a permeable reservoir. That way they have confidence that it won't migrate to places they aren't sure of, and that it won't contaminate a resource that they might one day find a way to get more oil out of. (Remember that most of the oil in the reservoir remains there and only a fraction is pumped out in most cases,)

thanks, Dave

I take it from your reply that buried disposal requires a purpose drilled well?

It is easy to see that new tech, or higher prices , can lead to an old field being brought out of retirement, but otoh, given the expense of nuclear disposal, buying up the rights to an exhausted field should be dirt cheap..

An interesting problem is that the atoms that split, about 5% each are silver, palladium, rhodium and ruthenium. Someone will likely want to recover those elements at some time in the future.

All but silver should be non-radioactive within 100 years. One metastable version of Ag108 has a half-life on 418 years. It "rearranges" it's nucleus, emitting a gamma ray but no particle.

Alan

Thank you for all these interesting articles you have posted. From these I have a greater understanding of oil, gas and coal production and this has allowed me to better evaluate many of the energy stories in the general media.

Current authorities on oil/liquid energy production are making overly optimistic projects for the very reasons stated in your posts. Many deepwater new finds are taking very long to develop and are not reaching projected output (Thunder Horse: 250k/day forecast, average for 3 years 100k/day and falling fast). Even though oil prices have sustained $100/ bbl the producers still are not making anticipated profits that would encourage faster field development, IMO.

Nearly 34 years ago I was studying engineering at the University of Missouri, Columbia and I took a course in energy sources and uses. The concept of peak non-renewable resources was introduced to the class and M. King Hubert's peak oil theory was examined. At that time we thought a peak in oil production would come before the end of the century (2000) but the world would simply switch to another form of energy. One interesting detail was the professor that taught the class was head of the nuclear engineering department at U of Missouri. His belief was that neither nuclear fission nor fusion would be providing an energy alternative after the peak. This professor's opinion was the implementation of solar, wind, tidal, and hydro power had great promise (when coupled with some form of hydrogen storage as a carrier) and would carry us forward. The year was 1980. I think he had more vision than most engineers of the time and even of today.

Mark S. Bucol

Saint Louis, MO USA

I noted that you had no eMail address in your profile. Could you send me an eMail if you would like to stay in contact ?

Best Hopes,

Alan

And cross-posting from Dave's Bit Tooth blog:

You can listen to the interview / show, "TWiE 103: When The Oil Drum Peaked," with guest Dr. Dave Summers (aka: Heading Out) at: http://www.thisweekinenergy.tv/?p=359

I'm really going to miss TOD. :(

Bob Tregilus

Co-host -

This Week in Energy (TWiE)

Here at the end of TOD, I think Dickens is an appropriate author to cite. And I'd like to toss out what may be perhaps an even more familiar and apt metaphor from 'A Tale of Two Cities'. "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times."

Here we sit at the apex of global industrial civilization. Available oil per capita peaked in 1979, http://peakoilbarrel.com/poat/ and has gradually declined since. Increases in NG and coal (esp. the past 10 years, esp. in China http://ts1.mm.bing.net/th?id=http://ts1.mm.bing.net/th?id=H.477268476900... H.4772684769004889&w=98&h=108&c=8&pid=3.1&qlt=90&rm=2 ) have kept us in an essential Net Energy Per Capita Plateau these past 30 years or so.

We have 'lived the good life', with the energy slaves available to us that kings of old could only dream of, as has oft been noted here. Yet at the same time the industrial machine's devouring of the planet's resources, our vaccuuming of the seas, our strippiing of the landscape - largely 'out of sight out of mind', except perhaps for the inexorable paving over of farmland surrounding our cities - has ravaged our home, the Earth.

Now we sit poised at the apex of many limits to growth - energy, soil, water, phosphorous, and perhaps the most significant: a stable climate. We have tipped the Holocene into the Anthropocene, and the consequences are only beginning to show themselves to us.

The Oil Drum was an oasis of sanity amidst the madness that engulfs us. I am sad beyond words to see it go, as the worst of times overtake the best with every passing hour.

Goodbye all.