Our World Is Finite: Is This a Problem?

Posted by Prof. Goose on April 30, 2007 - 9:20am

This is a guest post by Gail the Actuary.

We all know the world is finite. The number of atoms is finite, and these atoms combine to form a finite number of molecules. The mix of molecules may change over time, but in total, the number of molecules is also finite.

We also know that growth is central to our way of life. Businesses are expected to grow. Every day new businesses are formed and new products are developed. The world population is also growing, so all this adds up to a huge utilization of resources.

At some point, growth in resource utilization must collide with the fact that the world is finite. We have grown up thinking that the world is so large that limits will never be an issue. But now, we are starting to bump up against limits.

So, what are the earth's limits? Are we reaching them?

1. Oil

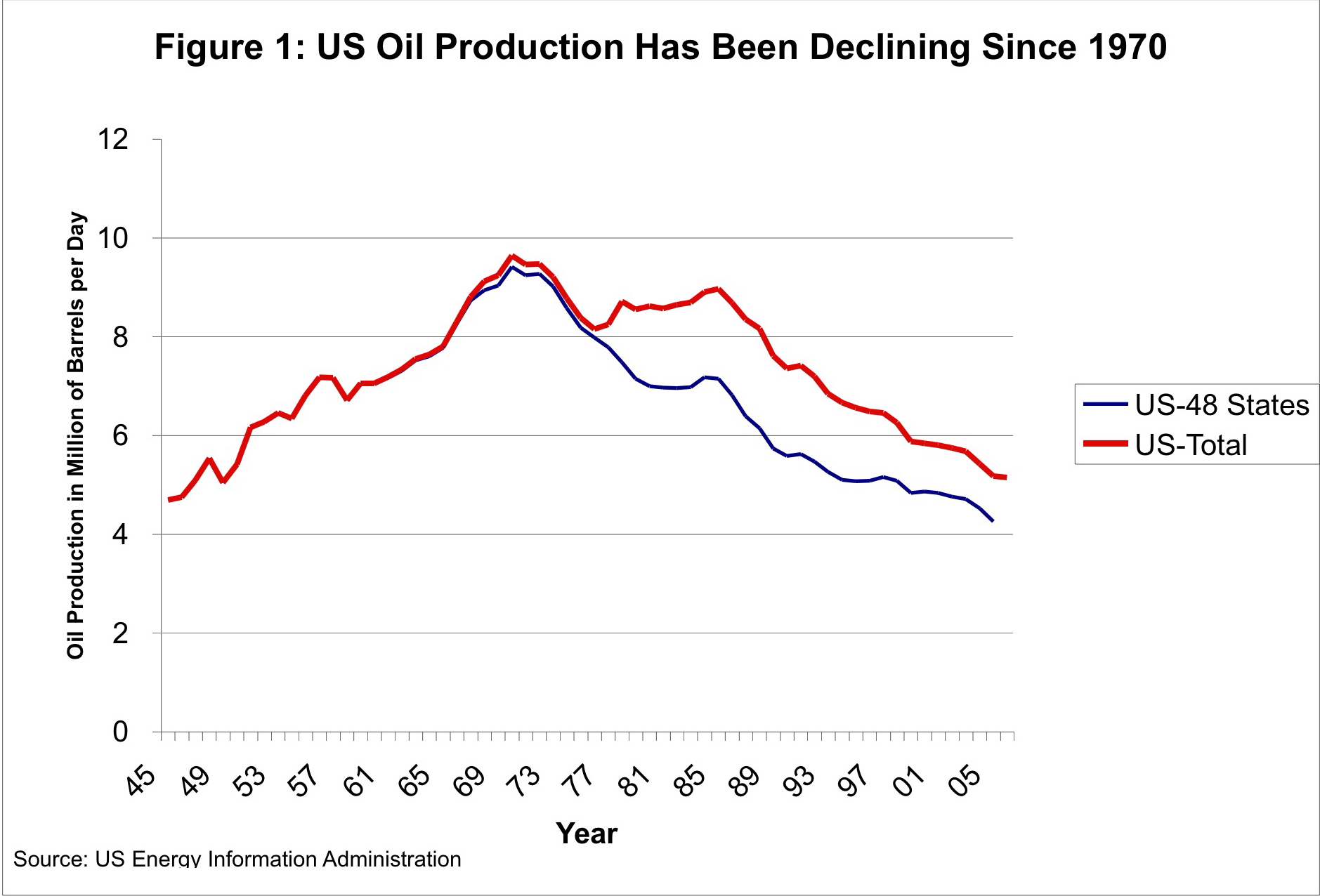

Oil is a finite resource, since it is no longer being formed. Oil production in a given area tends to increase for a time, then begins to decline, as the available oil is pumped out. Oil production in the United States has followed this pattern (Figure 1), as has oil production in the North Sea (Figure 2). This decline has taken place in spite of technology improvements.

There is now serious concern that world oil production will begin to decline ("peak"), just as it has in the United States and the North Sea. I discussed this earlier in Oil Quiz - Test Your Knowledge . A congressional committee was also concerned about this issue, and asked the US Government Accountability Office to study it. The GAO's report, titled CRUDE OIL: Uncertainty about Future Supply Makes It Important to Develop a Strategy for Addressing a Peak and Decline in Oil Production confirmed that this is an important issue.

Exactly how soon this decline will begin is not certain, but many predict that the decline may begin within the next few years.

2. Natural Gas

Natural gas in North America is also reaching its limits. United States natural gas production reached its peak in 1973. Each year, more and more wells are drilled, but the average amount of gas produced per well declines. This occurs because the best sites were developed first, and the later sites are more marginal. The United States has been importing more and more natural gas from Canada, but this is also reaching its limits. Because of these issues, the total amount of natural gas available to the United States is likely to decline in the next few years - quite possibly leading to shortages.

3. Fresh Water

Fresh water is needed for drinking and irrigation, but here too we are reaching limits. Water from melting ice caps is declining in quantity because of global warming. Water is being pumped from aquifers much faster than it is being replaced, and water tables are dropping by one to three meters a year in many areas. Some rivers, especially in China and Australia, are close to dry because of diversion for agriculture and a warming climate. In the United States, water limitations are especially important in the Southwest and in the more arid part of the Plains States.

4. Top soil

The topsoil we depend on for agriculture is created very slowly - about one inch in 300 to 500 years, depending on the location. The extensive tilling of the earth's soil that is now being done results in many stresses on this topsoil, including erosion, loss of organic matter, and chemical degradation. Frequent irrigation often results in salination, as well. As society tries to feed more and more people, and produce biofuel as well, there is pressure to push soil to its limits--use land in areas subject to erosion; use more and more fertilizer, herbicides, and pesticides; and remove the organic material needed to build up the soil.

Are there indirect impacts as well?

Besides depleting oil, natural gas, fresh water, and top soil, the intensive use of the earth's resources is resulting in pollution of air and water, and appears to be contributing to global warming as well.

Can technology overcome these finite world issues?

While we have been trying to develop solutions, success has been limited to date. When we have tried to find substitutes, we have mostly managed to trade one problem for another:

Ethanol from corn

Current production methods usually require large amounts of natural gas and fresh water, both of which are in short supply. Increasing production may require the use of land which has been set aside in the Conservation Reserve Program because of its tendency to erode.

Oil from oil sands and oil shale

Oil from oil sands requires large energy inputs, currently from natural gas, as well as fresh water, and creates pollution issues. Oil from oil shale is expected to require even more energy and fresh water.

Coal to liquid and coal substitution for natural gas

"Clean coal" and sequestration of carbon dioxide from coal are not yet commercially available, and are expected to be very expensive if they become available. Thus, coal production is likely to exacerbate global warming and raise pollution levels. If coal is used to replace both oil and natural gas, it is likely to deplete within a few decades, like the natural gas and oil it replaces.

Deeper wells for fresh water

If deeper wells are used, they will requires more energy to pump the water farther. In locations that use aquifers that replenish over thousands of years, the available water will eventually be depleted.

There are a number of promising technologies — including solar, wind, wave power, and geothermal — but the amount of energy from these sources is tiny at this time. Nuclear power also seems to have promise, but has toxic waste issues and is difficult to scale up quickly. A general introduction to alternative technologies is provided in What Are Our Alternatives If Fossil Fuels Are a Problem?

What if we don't find technological solutions?

We can't know for sure what will happen, but these are some hypotheses:

1. Initially, higher prices for energy and food items and a major recession.

If the supply of oil lags behind demand, we can expect rising prices for oil and gasoline and possibly other types of energy. Prices for food may also rise, because oil is used in the production and transportation of food. Recession is likely to follow, because people will cut down on their purchases of discretionary items, so as to be able to afford the necessities. Layoffs will follow. People laid off will find it difficult to pay mortgages and other debt, so banks and other creditors will find themselves in increasing financial difficulty.

2. Longer term, a decline in economic activity.

With fewer resources, economic activity is likely to decline. We will need to find replacements for many products in a relatively short time frame — heating fuel, transportation fuel, plastics, synthetic fabrics, fertilizer (currently made from natural gas), and asphalt, among other things. Living standards are likely to drop, because we don’t have infinite resources for replacing all the things that are declining in availability.

A graphic representation of how this might happen is shown in Figure 3. Real gross domestic product (GDP) gives a measure of how much goods and services the United States is producing in a year, in constant (year 2000) dollars. The "Fitted" line in Figure 3 shows the expected growth in real GDP, if growth continues as in the past. Scenarios 1 and 2 show two examples of how limitations on oil and natural gas might impact future real GDP. Scenario 1 shows a fairly rapid decline, starting very soon. Scenario 2 shows a slower decline, starting in 2020. If the downturn is still several years away, we have longer to plan, and a better chance that the decline will be more gradual.

3. Transportation difficulties and electrical outages.

Since transportation generally uses petroleum products for fuel, a reduction in the amount of oil available is likely to cause transportation difficulties. These difficulties may extend to all forms of transportation--automobile, trucks, airplanes, boats, and railroads, to the extent that fuel is unavailable due to shortages, cost, or rationing.

If natural gas supplies decline, electrical outages are likely, especially during high-use times of the year. Electrical outages may also result from interruption of transportation of other fuel, such as coal, to power plants, because of petrolum shortages. Outages may be one time events, or may be planned outages at certain times of the day, to compensate for an inadeqacy in the fuel supply.

4. Possible collapse of the monetary system.

This is perhaps the biggest single issue, and the most difficult to understand.

There is a huge amount of debt in the world today. When loans were made, the expectation of the lenders was that the economy would continue to grow as in the past--that is like the "Fitted" line in Figure 3 above. If this continued growth occurred, people, on average, would be a little better off financially when the time came to pay off their loans than they were when the loans were taken out, so they would have a reasonable chance of paying off the loans with interest. Corporations would continue to grow, and because of this continued growth, most would be able to pay off their debt with interest.

What happens if a scenario like that shown as Scenario 1 or Scenario 2 on Figure 3 occurs? When it comes time to repay the loans, people and corporations will be on average, worse off, rather than better off, than when they took them out. It is likely that many people will be unemployed, and cannot pay back their debt. Companies manufacturing goods that are no longer in demand are likely to be bankrupt, and thus will be unable to repay their debt. Organizations holding this debt, such as banks, insurance companies, and pension funds will find themselves in financial difficulty, because of the many defaults on the loans that are the assets of these organizations.

Two possible outcomes of widespread defaults come to mind. One is that there is so much debt that cannot be repaid that banks, insurance companies, and in fact the whole monetary system fails. The other alternative is that the government guarantees all the debt, so that the institutions do not fail. The latter approach would likely lead to hyper-inflation.

In either event, people and businesses would lose their savings, because money either wouid either be no longer available (first approach), or would be worth very little due to inflation (second approach). In either event, foreign countries would be unlikely to accept our currency in trade. Simple transactions, such as purchasing food or paying an employee, would become very difficult. Eventually, some approach would likely be found to circumvent these difficulties--perhaps a more barter-based approach--but this would be a huge change from our current system.

5. Failure of economic assumptions to hold.

We have been raised in a world where supply and demand are generally in balance. An increase in demand results in a greater price, which in turn leads to a greater supply. If the particular item isn’t available, substitution is generally available.

Once we reach geological limits, these basic principles seem much less likely to hold. An increase in energy demand isn't likely to translate into greater supply. Distribution of the limited available supply seems likely to reflect considerations other than price, such as rationing and long-term alliances. There may also be military conflict over available supplies.

6. Changed emphasis to more local production.

Two factors are likely to encourage local production and discourage international trade. One is the higher cost and/or unavailability of fuels used for transportation. The other is difficulty with the monetary system--either hyper-inflation or complete failure of the system. If there are monetary system problems, other countries are likely to want actual goods in trade, rather than IOUs or money. This requirement is likely to greatly reduce the amount of trade with foreign countries.

Food production is likely to be more localized, since this insures a continuous supply, and reduces the amount of fuel needed for transportation. If there are problems with shortages, people may choose to have gardens, so as to grow a few of the foods they need themselves.

7. Reduced emphasis on debt.

Once it is clear that future production is likely to be less than current production, as in either Scenario 1 or Scenario 2 of Figure 3, it will be very difficult to find any lender willing to provide long term loans, since if the loan is paid back at all, it is likely to be paid back in money that is worth very much less than it was at the time the loan was taken out.

If governments still have debt at this point, they will find it difficult to sell new bonds to replace the ones that mature. Businesses desiring to build new plants may find it necessary to accumulate resources for new plants in advance of their construction. Mortgages may not be available for prospective home owners, either.

8. Reduced emphasis on insurance and pensions.

If there are difficulties with the monetary system, insurance companies and pension plans will be among the hardest hit, since thy take in funds and invest them, and pay benefits later.

It is possible that a limited form of Social Security coverage may continue, but this is by no means certain. If a high level of inflation occurs (see point 4 above), benefits that have been promised to date will be worth very little. If a new monetary system is in place, it will be up to the government at that time to determine the level of benefits. Because total goods and services will be lower in the future (Figure 3 above), benefits to retirees will almost certainly be lower as well.

9. More people will perform manual labor.

As the amount of oil and natural gas becomes less available, more work will need to be done by hand, since the fuels to run machines will be less available. In order to encourage people to take jobs involving manual labor, manual labor will pay better in relationship to desk jobs. Because food is such ain important commodity, farming may be particularly highly valued, and may pay especially well.

10. Resource wars and migration conflicts.

If there is is an inadequate amount of a resource (water, oil, natural gas, or food), countries may fight over the limited supplies that are available. Conflicts are likely to spring up regarding areas where resources are plentiful.

Alternatively, people may choose to migrate from an area if resources become less abundant--for example, migration may occur if water supplies dry up, or if land is flooded due to global warming, or if declining oil supplies limit transportation. Receiving areas may not welcome the newcomers, leading to more conflict.

11. Changes in family relationships.

Families are likely to see more of each other, because of reduced transportation availability. Families may work more closely together, tending gardens and running small family businesses. Co-operation may be more highly valued by society. Divorce rates may decline.

12. Eventual population decline.

The food supply produced in the world today is many times greater than the food supply 100 years ago, before oil and natural gas were used in tilling crops, pumping water for irrigation, making fertilizer and pesticides, and transporting food to market. As oil and natural gas become less available, the food supply is likely to decline. Eventually, world population is also likely to decline, reflecting the lower food supply.

Conclusion

We cannot know exactly what the future will hold, if technology is not able to overcome the many issues associated with a finite world, including declining oil and natural gas supply, decreasing fresh water supply, and climate change. Whatever changes occur are likely to differ from location to location, as the world activity becomes more localized.

We tend to think of governments as fairly stable, but these too may change. Countries may subdivide into smaller units. Some have even suggested that groups of states may break away from the United States.

Educational institutions will most likely change. Fewer students will probably attend colleges and universities, and the subjects of interest will likely change. The sciences and agriculture or permaculture are likely to be topics of interest. More students may want to live on campus, if transportation is a problem. Adult education may become more important, as people seek to develop skills for a changing world.

Businesses will also change. Local businesses will become more important, while multinational companies recede in importance. Manufacturing will become less important, and recycling will become more important. Providing necessities will get top priority, while nice-to-have items will not sell well. Barter, or a new monetary system that substitutes for barter, may be the way business is done.

People may choose to live closer to work, or may work at home, so as to minimize costs associated with commuting. Some people may choose to live with relatives or friends, so as to save on utility costs. Eventually, many homes in undesirable locations may be left empty, and the parts of these unoccupied homes that can be used elsewhere will be recycled.

The next 50 years will certainly be interesting ones. Perhaps, with technological advances, some of the potential problems can be avoided. But we will need to work hard, starting now, to develop ways to work around the problems which seem to be ahead.

To Learn More

The Power of Community: How Cuba Survived Peak Oil 53 minute film, available for $20, tells the story of how Cuba adapted to losing over half of its petroleum imports after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Closing the Collapse Gap: The USSR Was Better Prepared for Peak Oil than the United States Humorous talk by Dmitry Orlov

The Long Emergency: Surviving the End of Oil, Climate Change, and Other Converging Catastrophes of the Twenty-First Century Book by James Howard Kunstler

Discussion Questions

1. What are five things that might improve after world oil production begins to decline? (Hint: Consider exercise, weight problems, family situations, etc.)

2. If there is a decline in oil and gas production, how do you expect the large amount of debt outstanding to resolve itself? Do you think there will be monetary collapse, hyper-inflation, or some other solution?

3. Do you expect that families will have more or fewer children after oil and natural gas production begin to decline? Why?

4. How can businesses prepare for interruptions in electrical service?

5. What types of buildings are best adapted to frequent outages of electrical service? Which buildings are likely to have the most problems?

6. What vocations appear to be most likely to be useful for supporting a family, after oil and gas production begin to decline?

7. What changes might a college make to its curriculum, to better prepare students for the changing world situation expected after production of oil and natural gas begin to decline?

8. In Figure 3, real GDP in Scenarios 1 and 2 are shown as changing in relatively straight lines. Could alternative scenarios have the lines zig-zag or drop suddenly? What real world situations might cause different patterns?

We hope that you will use the reddit and digg buttons for our authors, it helps them get readers for their hard work...and seeing as how this is a good "primer" kind of post, this would be a great first read for new people.

Thanks.

There is a way to have continuing economic growth with a finite, fixed resource base (and a stable population that is within the carrying capacity defined by those finite resources). Any economic growth that happens under such circumstances must be due to intellectual development. The products of human creativity and scientific discovery can lead to more efficient usage of those finite resources. Demand can increase for products that require increasingly fewer resources to produce. Many of the fine and popular arts, for example, require only small material inputs, and with the applications of technologies such as digitalization, those inputs can be continually reduced. Yet the arts have expanded to become a huge component of our modern economy, and there appears to be very few constraints limiting their continuing growth in some form or another, other than the obvious ones of the discretionary wealth and available leisure time of consumers.

While some level of continuing economic growth might thus be possible under a stable resource base, my guess is that we are talking about a very low rate of growth -- maybe 1-2% annually at best. It also must all be hard growth rather than easy growth. In other words, the growth must be genuinely earned through real improvements in humankind's intellectual and cultural patrimony.

Perhaps there is a way to have continued economic growth for awhile, but even at 1 or 2%, the music has to stop somewhere, sometime.

The key, regardless, is that total material production and consumption must stabilize and decrease soon because we do not have enough planets for our current level of consumption, much less increases in our current level of consumption.

In any event, economic growth, as represented by GDP, has become an increasingly flawed parameter to even approximate well being. We need to focus on other measures of well being, which may or may not be reflected in changes in GDP.

Even within the strict context of GDP, the number is not a good guide to economic well being since most of the increase s in GDP over the last couple of decades has gone to the very rich. At least in the U.S. the level of inequality just increases year by year. To focus on the gross overall GDP or even the per capita GDP is a terribly distorted way of looking at the economy.

And then we have this perverted way of looking at greenhouse gases. The Bush administration prefers to focus on intensity as if the overall level doesn't matter as long as we are becoming more efficient. Well, efficiency isn't getting us where we need to be. Whether it could ever result in the overall reduction of GHG is a matter of debate, but in any event, the overall level needs to be capped. If, within those constraints, economic growth continue for awhile, perhaps that is acceptable.

A further related note. As more and more of us economize,localize, and produce, our efforts will larely not be reflected in GDP. But our well being will increase. The religion of economic growth is a curse.

NO, there is not "a way to have continuing growth with a finite, fixed resource base."

Growth is growth. Any increase in resource use beyond its capacity to replace itself means collapse.

We are not going to think ourselves out of this. This is the first canard that must go away. If you go to the Sudan and tell the starving there to just think about food and everything will be all right, you will be beaten to death. Then, if they are smart, they will eat you.

Do not tell me that people will grow an economy based on art. That is specious at best. Have you heard of the Tulip bubble?

What all Westerners and much of the rest of the world must come to realize is that a growth economy is a poisonous illogical, cancerous, waste of time and resources designed to enrich a tiny minority and screw the rest. Give up this paradigm. Live outside the patriarchy, escape the mean daddy paradigm.

The system is closed basically as far as mass goes but its a open system for energy primarily from the Sun but in general fusion creates a open system vs energy and breeder style fission effectively creates a open system. Also mining of solar system creates a system that is effectively open for critical raw materials also of course nucleotide synthesis can be used if needed and if energy is abundant. A element synthesizer orbiting close to the sun can provide effectively unlimited amounts of elements for a price at a finite rate.

I know it sounds like science fiction but nothing I said is not doable starting with todays technology it a engineering problem.

The problem is EROEI cannot be solved simply and constrains the system. The real constraint is thus EROEI which is constrained by...

E=mc^2

This constrain is one we don't know how to beat yet.

Surely you mean, "....is constrained by the Second Law of Thermodynamics...."

E=mc^2 has nothing to do with the case. In fact, if we ever get Fusion working (which we almost certainly wont) then E=mc^2 will solve our energy problems.

We're depleting the capacity of the sky to act as a heat sink?

Yeah yeah he knows, it was just to get you out posting! Welcome :)

Growth is growth, but there are different types of growth. Of course, you and everybody around here is thinking about exponential growth most of the time. Take a second and imagine a logarithmic growth curve, or better yet, a curve that approaches but never reaches an asymptote, like the logistic growth curve. Those curves allow for endless growth with an endlessly shrinking growth rate.

Asymptotic curves are what we can expect in the long run for most processes.

You didn't read what he wrote. He said:

"Demand can increase for products that require increasingly fewer resources to produce."

i.e., he is not talking about increasing resource use. He is talking about producing more with the same level of resource use - i.e., sustainable growth.

Consider, for example, the situation where a widget takes 1% less resources to produce every decade due to technological improvements. Production rate can grow indefinitely on a fixed rate of resource consumption, or production rate can remain fixed indefinitely on a finite, non-renewable resource. So long-term growth is possible, at least in theory.

In practice, there is the potential for long-term growth as well. Our energy use could expand enormously before solar would be unable to supply it, and - with enough energy available - projects to increase other resources (such as deorbiting asteroids for mining, or large-scale desalination for fresh water) may become possible.

In other words, there is a much weaker case for impending terminal decline of economic growth than there is for impending terminal decline of oil supply growth, and conflating the two like this does little more than dilute the peak oil message. If you are terminally pessimistic about everything, nobody will listen to you about anything.

So next year the same amount of nutrition, sunlight, water and care will product two turnips where this year we only have one. I don't think so. Maybe it's semantic - we could have qualitative change. We need it.

Growth is "more" - an increase in size, quantity or number. 2% is still a doubling in 36 years or so.

cfm in Gray, ME

No - we were discussing economic growth, not agricultural growth. The two are different.

In particular, with synthetic goods, we have more control over the production process, meaning there is more scope for improving efficiency.

Sure you can produce some widgets more efficiently for a few year, but for infinite sustainable growth you have to produce every widget more efficiently for ever. That is utterly impossible, Moore's Law or its equivalent lie in wait for you sooner of later - and normally sooner. Eventually, all else failing, Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle will hit as you try to make widgets measuring less than Plank length.

However, putting that aside, given this potential underling infinite supply of more efficiently built widgets, you have to find the energy and investments to switch to sustainable energy using solar or wind, and keep growth going at the same time. That's a bit like doing a valve job on an engine while the engine is going! As the old Irish joke goes, "I wouldn't start from here.";

Surely there is a gap between terminal pessimism and being a realist - although I can't see much difference at the moment.

Well, realists realize that these problems are at the very least centuries in the future, and more likely millenia.

It depends on which problems you're referring to.

Peak oil? Definitely less than centuries, much less millennia. Current oil demand levels would consume over 3T barrels in the next century, which is about the sum of petroleum believed to exist, including tar sands and oil shales.

Peak energy? Centuries or millennia. Solar irradiation onto the earth's surface is more than ten thousand times the world's current power consumption (link). Converting that to electricity (~30% efficient) and placing solar cells only on infrastructure (~3% area for US-like country) still gives a thousand-fold increase in available energy, without even leaving the planet.

Of course, there's only so much energy available in the solar system - the sun only produces a finite amount of radiance - so there are theoretical limits to growth of energy consumption here. But those theoretical limits are so enormously large that they're utterly irrelevant right now.

So we need to be a little careful with terms. Oil supply? Bound to peak soonish. Energy supply? Functionally limited only by ingenuity and capital.

Conflating those two is not useful.

You do realize that Moore's Law is (a) not a law (it's just an observation), and (b) says the opposite of what you're saying?

If you wished to provide evidence that infinitely-increasing efficiency is impossible, you'd do much better to argue from the perspective of thermodynamics. It's not clear that production must inherently be non-reversible, though, meaning there's no clear path to proving that continually reducing the energy requirements of a recycle/produce system is impossible.

So, really, all you're saying is that you believe continually-increasing efficiency is impossible. That you believe something does not make it true.

Why would you make widgets of less than Planck length? You'd recycle and reuse the finite resource base, including the resource requirements for that in the overall production requirements.

That'd lead to a faster and faster update cycle for the widgets in the constant-consumption-rate scenario, of course, but that's really not a practical concern - demand for a type of widgets typically follows a logistic curve (see, for example, railway installation or cellphone adoption), meaning the number of units we want to produce would eventually approach an asymptote, shunting us into the fixed-production-rate scenario.

Not at all.

It's like doing valve jobs on a fleet of engines while the fleet is still in operation. And that happens all the time.

If you don't see a difference, there's two cases:

Never underestimate the chances that you don't know everything. Skepticism about your beliefs is tremendously important.

i.e., that you believe something does not make it true.

Neither of us, thank God, can know the future. However, I have great difficulty in imagining one in which we mange to continue expanding the production of everything (including, I presume people) for ever. There are many constraints to prevent this and I touched on only a few in my post yesterday.

Honesty must compel you to admit that all previous civilizations we know of have collapsed and that there is no particular reason to expect our society to be different.

I agree that such a scenario is beyond unlikely.

The rate of population increase has been going down for quite a while - both as a percentage of current population and in raw millions per year. Indeed, the UN projects world population will peak at 9.2B in 2075, and the cessation of population growth will mean that only per-capita factors can drive increased consumption.

Some of that will happen, but - as the last few decades in Germany suggests - eventually people's consumption levels will saturate and stabilize. There's no particular reason why consumption rates of anything should increase indefinitely - like I said, that kind of thing tend to follow a slow-fast-slow curve that eventually approaches an asymptote.

A lack of growth in consumption of resources doesn't imply a lack of economic growth, as mentioned previously. A lack of growth in consumption of goods, though, might - economics is the study of allocating scarce resources to competing uses. If resources aren't scarce, then the notion of "the economy" is not entirely well-defined. Some fiction looks at that kind of scenario, though, and what might occupy humanity's time and energy. "Star Trek", oddly enough, is probably the best-known example.

Not at all.

First, I don't agree that all previous civilizations have collapsed, and I think that's either an ethnocentric or naive view. Some groups of Australian aborigines have oral records going back - literally - tens of thousands of years, as confirmed by references to geographic features that are not present anymore but can be determined to have been present at the time. I haven't seen particular evidence that they've "collapsed", unless you'd prefer to say they don't count as civilized.

Similarly, many of the native groups in North America were destroyed by conquest rather than collapse. That may represent (one of the) potential differences between our current (global) situation and previous (isolated) civilizations, which is that there's (a) a broad-based desire for peace, and (b) nobody "outside" our current civilization to come in and knock it over.

Indeed, the claim that every prior situation has "collapsed" is far from obvious, and needs to be backed up before it's taken seriously. And remember that universally-quantified claims ("for all") are not demonstrated by anecdotal evidence; merely claiming this or that civilization collapsed does not show that all of them did.

If you would like the claim that "all prior civilizations collapsed" to be taken at all seriously outside of the doomer community, you'll need to examine much less favourable cases than Easter Island. What about China, for example - it's been trucking along pretty well for a couple thousand years, despite periodic civil wars. Or Iceland - it has the oldest continually-sitting parliament in the world (the Althing), meaning it's had governmental continuity since it was settled a thousand years ago.

If honesty was going to compel me to say anything, it would compel me to note that either you have a very restrictive definition of "civilization", or that you simply haven't thought about whether your claim is true - and that I strongly suspect the latter.

Civilization comes from the Greek word Cives which means cities (by extension an urban, urbane, and literate society).

Aboriginal culture was indeed long lasting (>60k years possibly) but was static, not constantly growing (which is where we started this thread if you can remember).

Aboriginal society introduced no innovations and was sustainable. They made the minimum of widgets the same way for long periods of time and eschewed agriculture.

As I said before, you need to be much broader when attempting to supply evidence for your claim. You've noted that your definition does not support Aborigines as "civilized", but you've failed to address any cases that your definition does cover.

What about China? It's had large cities and literacy for millenia. When did it collapse?

What about tiny, harsh, isolated Iceland, surely a prime candidate for collapse? It's done pretty well for itself over the last thousand years (although it may not have had cities per se until about 250 years ago).

In fact, if your definition of "civilized" is "city", then what about all the major cities - Paris, London, Venice, ... - that have continually existed as large and stable cities for well over a thousand years?

You really haven't provided any evidence for your claim that all prior civilizations have collapsed, so how could you possibly expect anyone to believe you unless they already agreed with you? (That's one of the key dangers of insular communities such as Peak Oil, by the way - you get so used to people sharing the same beliefs that you can forget to check whether those beliefs are actually true.)

Hi Pitt and Le, (and others),

I like the conversation.

Just wanted to note about Easter Island AKA Rapa Nui

http://www.americanscientist.org/template/AssetDetail/assetid/53200?full.... It looks like the history was a bit more complex than the story one usually hears.

Professor, please excuse my ignorance, but most folks, including me, are not knowledgeable enough about this entire "Peak Whatever", GW, Super Volcanoes, Meteors, Gamma Rays, etc. to even pose rational questions.

What we want to know, is: How much of any of this, from any side or expert, is bullshit, and how much is something we ought to worry about?

We've seen the films, read the publications, and listened with rapt attention to pronouncements on all of it from hundreds of experts, celebrities, politicians, and Bubba down at the local watering hole. But we still don't have an answer.

I do enjoy reading your posts and the oildrum in general, but all the analysis doesn't answer the basic question posed above.

Help us out, please. We have lives to live.

No one really knows for sure. At best these are all educated guesses. I'd really like to see an IPCC-style panel address global energy/water issues.

Do the best to prepare at whatever level you deem is reasonable.

If worst case scenarios do come to pass (not saying they will), it may be that any preparation (short of a Vault) could be fairly worthless anyway. :)

If you don't want to study the science, then you must accept an "Argument from Authority". Internet blogs run the Gamut - from those who think the earth is 7,000 years old or don't believe in thermodynamics, to very knowledgeable Phds with years of experience.

The best way to sort out the silly stuff is just reject those who don't believe in the basic laws of physics (or evolution etc) or those who have a political philosophy so set on some agenda (like avoiding government taxation or control) that they are willing to bend all facts.

I would recommend reading "Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update" It does a good job explaining how exponential growth crashes into a wide variety of limits and tends toward collapse. Unthinking creatures follow population booms and busts. And so do thinking creatures that refuse to think (or act). It may be a tough book to get into, but it will pay back far more understanding than reading hundreds of posts.

If that book is too technical, then try "Plan B 2.0" by Lester Brown. It does not do as good a job of explaining the theory behind why systems collapse, but it does have a great list of all the limits the human race is crashing into. And it has helpful ideas of what can be done to act smarter.

There are also a bunch of "state of the planet" type books from reputable sources like Science magazine.

gTrout, some good reads, of course you could go back to 1980 and read Alvin Toffler's "The Third Wave" and see every single issue we think is new now discussed then. His view then was that the time of the end of the worship of growth was THEN, 27 years ago. Was he correct in fact, but just wrong on the timing?

By the way, Toffler did not see the end of growth as growth was then (and now) narrowly defined as the end of human experience, far from it. But he did see it as the beginning of a change in human history as powerful (and as potentially chaotic) as the birth of the prior two great changes in wealth production, agriculture (recall that at what time, every human on Earth was a hunter-gatherer, now, not even 1% is) and industrialism (recall that at one time 90% of the human race was involved agriculture, now, barely 3% in the developed countries are), that would change at the core humanities way of existing and creating wealth and surplus. I will talk in another post about some of the directions we thought we would go back in those days, but there is a change a'comin', there always is, the only question is how fast and hard it will hit....and who will benefit (some will) and who will get hurt (someone always does)

Roger Conner Jr.

Remember, we are only one cubic mile from freedom

Malthus was in fact correct 200 years ago. A finite planet will not support an infinite population of anything. At that time no one could foresee how far we would overshoot that limit, but I believe we've done it.

| The problem will solve itself.

| But not in a nice way.

That's a very good question, but really unanswerable. If we are frank, there is an awful lot of BS written about PO (and everything else) - that applies to both sides of the argument. Anyone claiming to be able to predict the future with such accuracy is obviously a charlatan or a fool.

If you can't decide on the evidence yourself, then you would have to ask someone you trust to give a verdict. Personally, I trust the scientific method to eventually come up with the truth, but science is poor at predicting one-off events. Observation of events as they happen will be the only way to know for sure.

In the event that there is something to worry about, if you decide there is nothing that you can personally do that will make any significant difference, either to your own future or anyone elses, then the best thing is to ignore it, and get on with your life. Worrying about stuff you cannot change will only cause stress, to no useful end.

Then, every pronouncement on these issues (from whoever ) should be preceded by a disclaimer. Eg. "This is my opinion, and it's quite possibly complete BS." Logically, then, lacking any definitive proof, the avg Joe should ignore all of it, and deal with whatever comes his way, when and if it does.

Put simply, "Tomorrow will take care of itself". Right?

Therefore, why on earth should anyone consent to higher taxes, limited life style, and so on, "just in case"?

Thank you.

Logically - which is to say, acting rationally - he should do no such thing. Definitive proof is highly overrated, largely because it's almost entirely lacking.

If Joe wants to act sensibly, he should examine the arguments about the issues, kick their tires, maybe educate himself a little, and then make a reasoned judgement about which ones are most likely, how likely they appear to be, and what he should do about it.

Doing nothing until definitive proof exists is just silly. It's like not locking your car until it's stolen, since you don't have definitive proof of the existence of car thieves until then.

I have to agree with Pitt. Humans have a clever brain, why would it be "Logical" to pretend we don't and act like sheep?

Watch a movie like Titanic if you want to see what happens when people set aside rational planning for wishful thinking. It would have been a lot easier to save all the passengers if they didn't hit the ice berg in the first place.

That is the whole point of peak oil planning. 30 years ago the first population limit debates raged that we should not allow growth to get larger than the "lifeboat" that we live on. The people arguing for the limited lifestyle lost.

The next argument will be about who gets to be in the lifeboat.

Go read a "State of the Planet". I think you will find the water is up around your ankles. But don't worry about that because the Titanic can't sink! "God himself cannot sink this ship". Return to your state room. Have another beer. Ignore the highly qualified engineer saying ships of iron can and will sink. Do nothing. Watch more TV. Take out another mortgage. Buy another big car.

You won't need to consent to a limited life style. It will be the only choice available.

Hi Gene,

I like that you're asking a practical question. It may be difficult for people to respond, without knowing more. What are you most concerned about?

Regarding what Bob says:

"Anyone claiming to be able to predict the future with such accuracy is obviously a charlatan or a fool."

To me, it looks as if the crucial phrase here is "...with such accuracy...". It's not foolish to look at the problem - it's wise. No one can predict the future with accuracy. Still, we can say some things about the present. This means, we can say some things about the future.

There are (at least) two aspects of discussing "energy and our future":

1) The broad outlines of resource in terms of available amount and time.

2) The fact the resource is finite.

3) This means something.

The question is: What?

In other words, we can know something about the situation we are in, and then talk about what the changes will look like.

We can also say definitively what will happen if there are no changes. And that looks extremely bad.

Assume we don't want "bad".

How do we get "good" or "least bad"?

Okay, let's pull some things out of my arse. I view myself as an optimist at TOD, compared to many of the viewpoints here.

Supervolcanoes, Meteors, and Gamma Rays(I think you mean supernovas within a few parsecs) have a fraction of a percent chance of killing off, say, half the population of a continent of people in the 21st century.

Global warming is the next most likely event, but it is quite difficult to predict the weather next week, much less accurate atmospheric forcing over the course of a century. All we really KNOW is that Northern Hemisphere average temperatures in the last decade are scary(read: beyond all reasonable models we were using), and the steadily(read: reversal of trend is the hardest task humanity as a whole has ever faced) climbing atmospheric CO2 is scary. 60% confidence level of beginning to melt Greenland and wiping out most of the arctic glaciers in the next hundred years, flooding most sealevel islands and coastlines gradually. 75% confidence level of causing over 10% of the earth's population to relocate their home through agricultural or flooding problems.

Ecological problems and 'The peaks' are the only virtually assured disasters. Ocean fisheries, forests, topsoil, aquifers, and accessible hydrocarbons are all being depleted at rates that simply can't mathematically continue for another 93 years.

Ecology

Invasive species are destroying previously isolated flora and fauna, and WILL continue to, for lack of ability and more often, lack of caring(we're annihilated stronger hazards than the wild boar): 100% confidence. Industrial pollution WILL continue to sterilize or contaminate riverwater: 100% confidence. Desertification WILL cause large food shortages(and accompanying wars, which we can see in Africa now) and shifts over to less nutritious foods: 95% confidence. Fresh water WILL become a semiprecious commodity in much of the world that now takes it for granted by basically mining it: 95% confidence.

Hydrocarbons

Oil, gas, and coal WILL become the most important strategic assets in the world, the subject of numerous wars: 95% confidence. That one of those wars will be of the same scale as WW1/WW2: 30% chance. Whether the first world can replace most of their use without cascading collapses of industrial infrastructure (and eventual dieoff) is up for debate. I give it 90% chance we can do it, but 80% chance that it will be looked back on as at least as dark a period as the Great Depression. Partially because if there ever was a trigger for the fiscal problems of the United States to explode(the housing market hasn't done it yet), it's peak oil, which would put our trade imbalance so much deeper in the red than it already is, it threatens our credit rating, and thus, our status as an anchor currency. Chance of hyperinflation in the US after a global peak is discerned: 60%.

After that, there's the matter of the 'true' price for oil. Exports will dry up much faster than total supply when a peak becomes apparent, as countries nationalize, strategically reserve, and in general tighten their supplies(aside from rising internal consumption, which is what the much-repeated 'exportland' term refers to). Call it a 1-5% decline rate, paired with a 5-15% decline rate in exports. The 'true price' is a very subjective matter, masked partly because oil becomes the anchor currency in the short term.

Alternative energy is poised to grow to large-proportion-of-most-economy sized proportions, at least for a while. Regardless of what romantic environmentalists like to think, 'Powerdown' is not an option. 6.5 billion people living at 18th century levels of industrialization is simple not possible, preferable, or something they will accept. Nor is mass genocide acceptable so that the few survivors can 'live off the land'. Whether it can take hold fast enough is a big question. I have a lot of optimism - thus far alternative energy is a hobby. There is every reason to believe that it is possible to bring up the level of innovation if we take it as seriously as we do major wars.

I appreciate all the comments and opinions, I really do. But ya' know what? I've yet to hear from "Professor Goose", who was the author if I'm not mistaken.

And I did mean Super [i]Volcanoes[/i] - eg: Yellowstone. Although Super Novae (or the Super Flu ) are yet more "things we should fear". Sorry, y'all. I don't scare easily. Which really pisses off politicians, preachers, and certain special interests. Sometimes people need their ricebowls kicked over, and I'm an equal opportunity rice bowl kicker. They can deal with it. Or bite me. Don't much care which.

Hi Gene,

Are you still reading this thread?

If so, "Prof G" posted this for the author. The author herself is Gail.

I think she posted it in order to get feedback, and I take it her main desire is to educate people.

So, are you saying that you'd like to know "how scared" to be?

Another way to say this: "Are you wanting some guidance in how to assess the importance of 'peak oil'?"

My take on it is that Gail is writing to help give people the information they need in order to evaluate our situation. So, she may not want to tell you how afraid you "should" be.

Rather, she may want to give you facts, and then ask "What do you think we all ought to do?"

Robert Hirsch, who is the author of the 2005 Hirsch report, said in a public interview that this was the most frightening thing he's encountered in his lifetime. It might be useful to you to look up his writing. Check out http://www.energybulletin.net/28895.html

Perhaps the question to ask is "Why is he afraid? And why is he also concerned about being seen as alarmist?"

Aniya, yes I still follow this, and other threads, etc. You asked where I was coming from with this line of questioning.

I'm retired now, but at one time I was a senior internal consultant and statistician for one of the worlds largest manufacturing corporations. At that time one of my constant concerns was over-reaction to normal system behavior by the management of those business and manufacturing systems. People are generally not comfortable with variation, and tend to react in ways that are not only unpredictable, but dangerous to the proper and normal functioning of the system.

My concern now is the same: one of over-reaction by the public and by policy makers. I have the same issues with the Climate Change people. To a layman a 90% confidence is close enough to a "sure thing" to start stockpiling food. To a statistician it's barely noticeable and is certainly not sufficient to engender drastic corrective action unless the fundamental physics of the situation support such action. Statistically, "action" taken within the "6 Sigma" control limits is generally a waste of time and resources and often will create a problem where none existed prior to the "adjustment". This is all predicated on the existence and demonstration of a stable system however. Since I seriously doubt whether such stability exists (in the statistical sense ) for either Peak Oil or Climate Change my inclination is to prod the proponents of such analysis to establish the basic requisites to obtain a 99.73% conf. in their conclusions before any significant action is contemplated.

The above is, of course, greatly simplified, and would require significant work to establish the appropriate probability distribution(s). If such work has been done, I've not seen it. What I have seen is a great deal of "I believe", without even so much as a reference to either traditional or Bayesian analysis, let alone a serious consideration for the natural variance and/or chaotic behavior of the system being discussed.

You appear to be talking not about "confidence" but about "likelihood", which is very different.

An event with around a 100%-90% = 10% likelihood - such as flipping a coin three times and getting "heads" each time - is (as you say) statistically boring. Things that are 10% probable happen all around us all the time - it's not even two standard deviations (assuming a normal distribution).

By contrast, saying that there's a 90% chance X caused Y is very different. The key is to realize that the probability of any random event being responsible for any other random event is tiny - much less than 1% - so 90% is a huge deviation from that zero-knowledge value.

Think of it this way: there's a million people in the city, and you know one of them killed a man. Without any other information, you assign a 0.0001% chance of guilt to everyone. By contrast, if there's a 90% chance Bob killed the man, that's an enormous difference from 0.0001%, and hence is highly statistically significant.

You're analyzing the situation completely incorrectly - you're confusing probability distribution of occurrence with probability of causation. Those are not the same thing, are not comparable, and can not be correctly analyzed as if they were.

In particular, the probability that X caused Y is typically not normally distributed, so it doesn't even make sense to talk about its standard deviation.

You would be well-advised to think very carefully about your use of statistics in shaping your beliefs; it's an important thing to get right.

Trust me, I do know the difference between a probability distribution and a frequency distribution. And StdDev can be calculated based on any known distribution, including Poisson, and others besides the Gaussian. But, it isn't going to make any difference to anyone if we argue about it, so let's agree to disagree, shall we? As I stated earlier, I'm retired.

Have a nice day.

Not based on your comments here you don't.

Fine - what's the standard deviation of "90"?

Consensus scientific opinion is that global warming is 90+% likely to be caused by human actions. How are you analyzing that number to determine it's statistically insignificantly different? Different from what - what's your null hypothesis? It makes no sense to say a number is "statistically insignificant" without saying what it's statistically the same as, and there's no indication there's any sensible baseline to compare to here.

It's like saying "7 is a high score" without knowing what sport the score is from.

Saying "90% is statistically insignificant" while talking about the "6 sigma level" makes it pretty clear you're thinking about the probability of a normally-distributed random variable being a certain distance away from its mean value, and that's a completely nonsensical thing to talk about when discussing a number like "90% chance humans cause global warming".

You don't need to admit that's what you were doing; just don't tell other people to do it.

Hi Gene,

Thanks for responding.

re: "This is all predicated on the existence and demonstration of a stable system however. Since I seriously doubt whether such stability exists (in the statistical sense ) for either Peak Oil or Climate Change..."

A couple of qs, which may help me understand what you're getting at:

1) When you speak of a "stable system", do you mean the system of industrialization, housing, food, transportation and etc., all of which rely on a continuous input of oil and natural gas, for a given percentage of the earth's population?

2) If this isn't what you mean, could you possibly explain in different words? I'm not quite getting what you're saying here.

3) When you say "...Peak Oil or Climate Change..." Are you putting these together in some sort of category? If so, could you explain what it is you believe they have in common?

As I see it, the two notions are very different. "Peak Oil" refers to the beginning of a decline in world supply flows (input), which will never reverse, given certain assumptions involving the extraction rates. In other words, it's a turning point in rate of extraction of geologically-imposed total amount. (I could try to say this better, I'm just giving it my best for the moment.) Let me try again. "Peak Oil" is about humans extracting oil from deposits in the earth.

Climate Change, though is about trying to assess current climate temperature trends in terms of causation.

I don't see many similarities in looking at how to understand these problems, other than ones we might draw just for the sake of discussion.

Do you? If so, what are they?

4) I do see overlaps in looking at ways to address each problem. Others have written on this as well. See http://www.energybulletin.net/24529.html

However, it is entirely possible (not desirable, but possible) to address each problem in isolation.

5) The issue of oil depletion (and impending or already-upon-us decline in oil flow input) I see as a much easier problem to analyze, in it's broad outline, as we have a straightforward history to use, and some fairly straightforward facts about how the extraction process works.

Of course, looking at the dependencies, (esp. what we might describe as economic dependencies) engendered by humans use of oil is another, more complex problem.

In terms of analysis, here's a simple one: Just as an example:

1) If the oil flow input to the world's people were to suddenly cease tomorrow and never return,

2) The result would be massive economic disruption and severe problems in people meeting basic needs for food, water, medical care, transportation and work in most of the world.

I won't use the word "economic collapse", though we might.

It's fairly easy to put numbers on what the input is.

It's more difficult to predict the effects of the abrupt cessation, though certainly possible.

3) Then, in order to talk about the effects of decline, we can say "Okay, let's back up a bit. How about instead of the entire flow suddenly ceasing, we had 90% of the flow suddenly cease. What would that do?"

And then, continue in this fashion, until we decided what kinds of decline rates would be tolerable, what kinds catastrophic for sure, and so forth.

One thing to do would be for an individual or family to look at exactly what dependencies they have. Then decide if and how they would survive if these input flows were to cease.

Just my thoughts on these subjects.

PG, Leanan and TODers...

Knowing how frequently you urge us to digg articles... did you catch the "Smart Digg Button for Firefox" released last week?

http://neothoughts.com/2007/04/27/firefox-extension-smart-digg-button/

Might be useful to you?

This article is aimed at a broader audience than the regular TOD readers. Hopefully, it is something people would not feel uncomfortable e-mailing to their friends.

I tried to condense the story as much as possible, so as to keep the article a reasonable length.

This is an excellent overview, and I shall probably email it to a number of people.

I do have a comment on item #4,"Possible collapse of the economic system."

You write "Two possible outcomes of widespread defaults come to mind. One is that there is so much debt that cannot be repaid that banks, insurance companies, and in fact the whole monetary system fails. The other alternative is that the government guarantees all the debt, so that the institutions do not fail. The latter approach would likely lead to hyper-inflation."

An additional possibility is deflation, as happened during the Great Depression.

During a deflationary cycle, waves of bankrupcies eliminate a lot of capital, and the "normal" growth cycle goes into reverse. Desperate people are selling, nobody is buying, the value of assets declines and the value of what currency remains increases.

If a house costs $20,000, and gas is 50 cents a gallon, it won't do you any good if you are out of work, with creditors lining up at the door.

Central banks would, of course, do everything in their power to inflate their way out of this, but once a deflationary cycle begins it is extremely difficult for them to do anything about it. Just look at Japan during these past 15 years or so, or any country during the Depression.

I had to laugh at the insults hurled at a poster who mentioned it may be possible to beat the 'LAWS' of thermodynamics.

Those laws only apply to a CLOSED SYSTEM. If the Ether exists which it DOES (call it what you want...ZPE, quantum foam, virtual particles), the laws of thermodynamics do NOT apply.

Geez, I'd have thought with all the high paid braintrust on this board, someone would have known about it.

Want some hope? Do some research. Read some books. Read old papers on the Ether. Research Tesla and what he really knew. You've been hoodwinked...sucks doesn't it ?

yes, that's quite funny, but you shouldn't joke about it. There are some nuttos out there who actually believe that stuff.

Yeah, nuttos all right... :)

Thank goodness more people don't believe it or we might actually come up with a solution to the 'energy problem'.

In fact you know what's even funnier, all the nutters that believe that Relativity and Q/M crap:

1) Length goes to zero, mass goes infinite, and time stops at the speed of light.

2) EMPTY space can be CURVED...bwaaahhaaa

3) The speed of light is absolute and constant in the vacuum irrespective of ether spin zone.

4) Gravity is caused by GRAVITONS....bwaaahaaa!

5) The universe is one big probability function ala quantum mechanics...and stuff only 'collapses' when it is observed.

6) There might be 11 dimensions and you might exist in all of them.

Go back to sleep...

I have never really looked into it but you make some interesting points.

Were all of Einstein's derivations Algebraic manipulations?

Did Lorentz come up with his transformations before Eninstein published the theory of relativity?

(Einstein's derivation is below)

http://www.bartleby.com/173/a1.html

How strong in your opinion is the experimental evidence for item (1) in your post?

IMO thanks to PBS (via their "educational" shows) - all pseudo-intellectuals now believe in item (6) of your post and have heard of string theory.

thanks in advance for any response!

(PS: My knowledge of Physics is limited to Physics 101 and 102 from an old edition of Resnick and Halliday)

I believe it was Tesla who said Relativity was copped from one of his fellow country men written in the 1700's. I'm sure you could find the quote if you search for it. Tesla did not believe in Relativity and did believe in energy from the vacuum/ether.

He also had his dynamic theory of gravity that related gravity to the E/M interaction. Conquering gravity via E/M was his life's goal, but you won't find much written about it. You might try William Lyne's book, Pentagon Aliens, for some revealing info.

As for Relativity, I am of the opinion after much reading and THINKING, that it is all BS to cover for the disappearance of the ether, but you should make up your own mind and use common sense. Do you believe a twin would come back younger after a round trip near the speed of light than their sibling ? Too many paradoxes for me.

They're both very reliable models that have predicted every physical interaction we can conjure up. If you can come up with a better model that makes predictions, you get a very rich prize.

That you can mischaracterize some nonproblems because of some popular science article youve read just means you're an arrogant dilletante.

Now Dezakin, calling someone a name does not further your argument. If you choose to believe those models, that's your right.

Dude, there are no gravitons.

I love all the contradictions in Physics that have to be explained away with continual fudging, 'normalization', curved space (curved 'nothing'), action at a distance (field with no intervening 'media'), and wavicles.

Another thing I think is rather revealing is the creation of 'phenomena' such as charge, mass, inertia, or 'field', without explaining WHY or WHAT exactly accounts for the property.

Do I have a better theory, I can prove. Nope. I suggest you read some early papers on the ether, or maybe you are a PHD already? But it makes a heck of alot more sense when you consider the existance of an ether to account for inertia, induction, wave propagation, etc. than a curved nothingness, action at a distance, and wavicles. I mean what is all this talk about ZPE, quantum foam, unexplained dark matter ? There are PLENTY of current day physicists who believe in the Ether, even though they may not call it that.

Don't tell me you believe the twin paradox scenario of relativity. That's a real winner.

Say I have an incompressible rod that is 1 light year long. I push on one end, the other end moves NOW. That is a signal that can beat the speed of light, which would have taken one year to reach the other end. Is that faulty reasoning?

If any of these "Ether" models test better than conventional physics models, they will be quickly adopted. Until that happens, they aren't really worth talking about here.

Hi mark,

Actually, while many of us place much stock in reason, science, study and discussion (I know I do), it's also the case that there's a lot of politics involved in science as it's practiced. This affects funding, positions, what is studied, what is "accepted" - and much else.

So, it is not necessarily the case that models are "quickly adopted". In fact, sometimes there's such a bias, it's reflected in the papers accepted for publication, and thus we get a self-reinforcing process. Just to speak in general.

Or, another way to say this is, watch closely what happens after the results of "Gravity Probe B" come out. http://einstein.stanford.edu/

We may be witness to a change of "model". We'll see.

I suggest you read some of the later papers on the ether. In particular, read up on the Michelson-Morley experiment. Michelson went into that intending to measure the speed of the ether relative to the earth, and came out with very strong evidence that the ether doesn't even exist. (Wikipedia links to the original paper! link)

Relativity drew on that evidence against the existence of ether, and has been a very successful theory - it's made a number of predictions that have all been passed, giving it a very high confidence as scientific theories go - see, for example, this discussion. It's a very strongly supported theory, so - fundamentally - nobody cares whether you like it or not.

That's simply how experimental science works.

You observe.

You draw conclusions from your observations.

You attempt to explain those conclusions.

You make predictions based on your explanation.

You observe again.

You amend your conclusions, explanations, and predictions in light of new information.

You repeat.

The question of "why" comes after the question of "what". That you don't understand that suggests you should educate yourself on the scientific method.

Yes, that's faulty reasoning. You're assuming an impossibility - a completely incompressible rod - and it's well-known that if you assume a contradiction you can logically prove anything.

Oh, so you're a professional then? Working to advance the field of knowledge?

Its been measured, literally thousands of times.

Its faulty the moment you assume you have an incompressible anything.

That is absolutely incorrect! The second law of thermodynamics applies only in a closed system. That is the law of entrophy, in a closed system it always increases.

"This law also predicts that the entropy of an isolated system always increases with time."

The first law of thermodynamics, the law of conservation of energy, does not give a damn whether the system is open or closed, it always applies.

"The first law of thermodynamics is often called the Law of Conservation of Energy. This law suggests that energy can be transferred from one system to another in many forms. Also, it can not be created or destroyed. Thus, the total amount of energy available in the Universe is constant."

The third law is also not concerned with open or closed systems. It deals only with absolute zero.

"The third law of thermodynamics states that if all the thermal motion of molecules (kinetic energy) could be removed, a state called absolute zero would occur. Absolute zero results in a temperature of 0 Kelvins or -273.15° Celsius."

Ron Patterson

Great Ron...you seem knowledgeable...

Do you know what the energy density of the vacuum is ? Wheeler supposedly calculated it at 10E94 g/cc.

Do you agree that it is possible to create an over-unity system by extracting energy from the vacuum ?

Amazing how physics kinda went from there is no ether, to 'well there is this quantum foam' and 'these virtual particles' that 'appear and disappear' out of 'nothingness' and by the way there is the ZPE which happens to sound an awful lot like the ether of Faraday, Tesla and others.

By the way, did you know that a mathematical model had been worked out showing why F=ma as the interaction of the accelerating mass with the ZPE ? Interesting huh, means that Inertia can be cancelled if the ZPE can be blocked.

But Tesla knew that...before 1900.

He was being tongue in cheek if you hadn't realized. Stop spouting nonsense.

Nope. Pseudoscience crap. The cold fusion guys were on much more solid footing.

BenjaminCole

My, quite a bit of handwringing today! Reminds of the Club of Rome days.

In fact, higher energy prices are already having the right effects: Conservation and substitution. Do you really think we face economic collapse because we drive smaller cars, use mass transportation, get plug-in hybrids, go to florescent bulbs? Move closer to work?

Already central cities are rebounding nicely, and I suspect suburbs may falter for a while.

Ethanol is not perfect, or other bio-fuels, but if fossil fuel demand flatlines (as it shows signs of doing at more than $60 a barrel) then bio may be very helpful. And we are getting better at bio all the time. Check out cattle-ethanol-methane combo plants. They use cattle dung to fire the ethanol plant and feed the wet distillers grain to cattle. Very postive energy plus, something on the order of 40-to-1. Probably can be done with pigs and potatoes too.

Also, check out graphs of world proven reserves., They keep going up, not down. Heavy oil out there in huge amounts.

There is an energy problem, but it is 90 percent political, not geological, or technical. 1) The USA seems to have the willpower of a fattie facing a diet, when it comes to real energy programs and 2) nutball countries control much of the world's light oil. These are problems, but do not spell the end of civilization.

Anyway, if you really really believe in the doomsday scenarios ahead, then go long on oil, or on oil companies (use the options market to really leverage up). Hmmm. No takers?

I suspect there are a lot of people on here who are long on oil companies for precisely that reason.

A life cycle EROEI of 40:1 for a dung-fueled ethanol plant? I'd have to see a good solid analysis to buy that - that's a better return than most conventional crude gets these days.

The rest of your comments seem peculiarly America- (or at least OECD-)centric. PHEVs, CFLs and moving closer to work don't apply to most of the rest of the world that uses kerosene light, travels by shank's mare and has a cottage business in the living room. You do realize this is a global problem, not just an inconvenience for the USA, right?

"My, quite a bit of handwringing today! Reminds of the Club of Rome days.

In fact, higher energy prices are already having the right effects: Conservation and substitution. Do you really think we face economic collapse because we drive smaller cars, use mass transportation, get plug-in hybrids, go to florescent bulbs? Move closer to work?"

Dear Mr Cole, are you new to TOD? These issues have been covered in great detail on previous threads. The issue with economic collapse comes down to the reality that the US has been able to shove its IOUs down the throat of China, Japan, Europe, etc only because it is the currency of oil commerce. Sadam was made an example of because he dared to take Euros for Iraqi oil. Sooner or later the rest of the world will have their fill of our IOUs and stop buying up US t-bills. Big problem for the US.

"Already central cities are rebounding nicely, and I suspect suburbs may falter for a while.

Ethanol is not perfect, or other bio-fuels, but if fossil fuel demand flatlines (as it shows signs of doing at more than $60 a barrel) then bio may be very helpful. And we are getting better at bio all the time. Check out cattle-ethanol-methane combo plants. They use cattle dung to fire the ethanol plant and feed the wet distillers grain to cattle. Very postive energy plus, something on the order of 40-to-1."

Could we have a link on this, please? I would be very interested to see their calculations.

"Probably can be done with pigs and potatoes too.

Also, check out graphs of world proven reserves., They keep going up, not down."

These wouldn't happen to be CERA's graphs, would they? They have been thoroughly debunked on this site.

"Heavy oil out there in huge amounts.

There is an energy problem, but it is 90 percent political, not geological, or technical."

It has been suggested repeatedly on this site that 'above ground problems' will be the chosen spin when PO really starts to hurt.

" 1) The USA seems to have the willpower of a fattie facing a diet, when it comes to real energy programs and 2) nutball countries control much of the world's light oil. These are problems, but do not spell the end of civilization.

Anyway, if you really really believe in the doomsday scenarios ahead, then go long on oil, or on oil companies (use the options market to really leverage up). Hmmm. No takers?"

Actually, I'm long North American oil and natural gas as well as PM producers. As my momma used to say, I've got my money where my mouth is.

BenjaminCole

Okay, here is one cite. There are others. The grain leftover after making ethanol is fed to the cattle. I thought it was called distiller's grain. If it is called something else, okay. In any event, it is fed to the cattle, and they eat it.

Nobody is doing this with pigs yet, although there is one guy who is converting pig poop straight into diesel oil...he says you let the pigs break down biomass into something more palatable for making energy....

The pigs-ethanol plant has a lot of promise as 1) Pigs grow more efficiently than cattle, and 2) potato yields per acre are much higher than corn yields....

Agricultural Situation Spotlight: Do Ethanol/Livestock Synergies Presage Increased Iowa Cattle Numbers?

Bruce A. Babcock

babcock@iastate.edu

515-294-6785

Chad E. Hart

chart@iastate.edu

515-294-9911

Increased ethanol production in Iowa and other Corn Belt states has led some to believe that the Midwest will no longer need to export any of its corn to other states or other countries. Farmer-advocates of more ethanol see such a future as making them free from reliance on unpredictable export markets, free from reliance on aging Mississippi River locks and dams, and free from worrying about the impacts of trade agreements and foreign competition. But such a future would not make the Corn Belt free of the need to export distillers grains, an ethanol by-product.

Efficient Use of By-products

A 50-million-gallon ethanol plant uses roughly 18.5 million bushels of corn. At the 2006 Iowa state-trend yield of 160 bushels per acre, this represents 116,000 acres of corn (80–90 percent of corn acreage in an average Iowa county). On a dry basis, 315 million pounds of distillers grains must be marketed.

The best use of this by-product is as feed for dairy and beef cattle. But Iowa has large numbers of hogs and poultry, not cattle. Without some resolution of this mismatch, most distillers grains from Iowa will continue to be dried and shipped to other states.

Dairy cattle can be fed a diet with 20 percent of their dry matter intake in DDGS (distillers dried grains with solubles), which translates into 13 pounds of DDGS or approximately 40 pounds of wet distillers grains per cow per day. Thus, an ethanol plant produces enough feed for roughly 60,000 dairy cattle.

Iowa currently has only 190,000 dairy cows in the state. Current Iowa production levels of 900 million gallons of ethanol would require 1.08 million dairy cows. This number of dairy cows would produce 15 percent of total U.S. milk production, so this increase is not beyond the realm of possibility.

Figure 1