Coal reserves and resources - a gentle cough

Posted by Heading Out on July 24, 2007 - 11:00am

I have written recently about some of the reasons that coal reserves, as currently understood, might not be quite as large, at present, as they are assumed to be. However, while I could continue on that tack for some additional time, it is perhaps time to give a gentle cough and suggest that there is perhaps a little terminologically inexact thinking in some of the discussions on the actual size of reserves, relative to the overall resource and that there is another viewpoint that should be considered in this debate. Particularly this relates to how much is left and how long it will last.

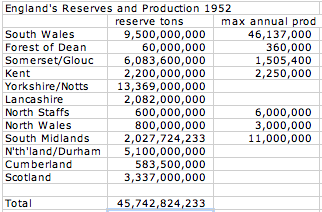

Firstly it should be recognized that a number of studies of coal reserves have put caveats on their numbers along the lines of “under current operating and economic conditions.” And so let me first put back up the table I posted in my last post , relating to the coal reserves of the UK back in 1952.

Note that this is coal that has largely been proved to be in place. However, in the time frame between 1952 and today it has not been mined or gone away, but it has become, at present, uneconomic to mine. And thus under current conditions it is no longer a reserve. And the one thing that those who write here should know better about assuming is the “current conditions.” Jeepers! We have spent over two years here accumulating convincing evidence that current conditions are not sustainable, and yet that argument is accepted, with little discussion, when it is proposed.

The problem that I have with Dr Rutledge’s argument , and those of similar inclination, is that they conflate physical and economic removal from the stockpile. But in reality is it to a large extent the economic conditions that currently prevail, not the physical ones. In large measure the coal is still there – and yes that includes quantities of Pennsylvanian anthracite. As was noted in the comments, one of the major reasons for the collapse of the industry around Wilkes Barre was that a mine broke into the bottom of the river . This caused extensive flooding and it was not, at that time, economically viable to do the necessary geological repairs to recover the deposits. So let me give you some numbers from a couple of studies on coal volumes, from back when it was not competing as ferociously with oil as it has been for the past few decades. (Because that is the prevailing condition we are moving into).

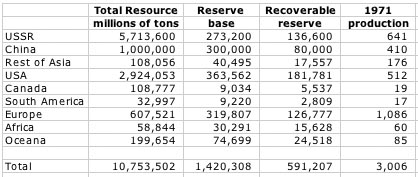

I am therefore going to start with the 1974 Survey of Energy Resources.

Now in these tables the resource is what is there, with no consideration as to whether it can be mined. Obviously it has to be of some finite thickness and there is some assumed maximum depth in the selection, but that is all. The reserve base is the amount that can be potentially mined (at 100% recovery) with the existing methods of the time, and economically. However (as earlier noted) mines don’t get all the coal, they only recover part of it, and thus the recoverable reserve is the amount that is likely to leave the property. And as you may note it is a small fraction of the grand total.

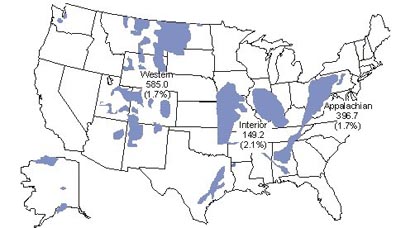

To refresh your memory this includes all the defined varieties of coal including lignite, (6,300 Btu per pound); sub-bituminous (around 10,000 Btu/lb); bituminous (14,000 Btu/lb) and anthracite. For the United States these can be found as shown in the following map (this information is from the EIA, and shows coal production in 2005, the table is from the late Bob Stefanko’s book “Coal Mining Technology – Theory and Practice).

Coal Production in the United States by region in 2005 (from the EIA )

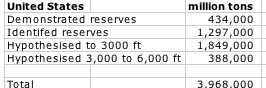

And the U.S. resource was considered to be when defined as -more than 1 ft thick for anthracite and bituminous, more than 2.5 ft thick for sub-bituminous, and at depths of less than 6,000 ft. Interestingly (as noted in the NRC report) the definition of inferred is for seams that are more than a quarter to three miles from an existing borehole (depending on the state for the definition).

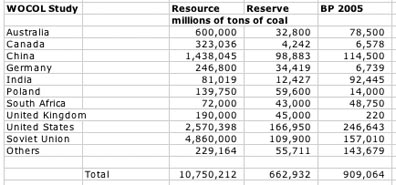

Note that the numbers are slightly different from that in the global table, since it includes depths below that considered by the larger projection. In overall total it has not changed much by the 2007 NRC report , although the component parts have. In 1980 the World Coal Study modified these numbers, considering that the minimum thickness for hard coal would be 0.6 m and for soft coal (brown and lignite) it would be 2 meters. There numbers (with a different selection of countries) was as follows.

Note again that they distinguish between what is there and what is, with the technology of the time, considered recoverable. The countries named accounted for 98% of world production at the time. For interest I have then added a column that gives the current estimate of reserves from the BP Statistical Review, 2006 ). The interesting number, perhaps, is the dramatic drop in the UK considered reserve. It does not indicate that there has been huge mining numbers over the past 25 years, but rather the constraint of what is currently economically viable. Re-sinking shafts is expensive, and the price is not yet high enough or the market large enough to justify the investment.

Now there are various definitions of what is viable and recoverable, and this is technology related, as much as anything else. You may remember that I pointed out (and Gail further noted) that as the mines have become mechanized the EROI has dropped. Our 0.2 hp miner can be quite effective, if rather slow. Further he can (as at Eglingham) work small mines that would not be economic for the larger machines and support structures of a modern mine. And that holds as true in China as it does in the rest of the world. It will also likely hold true in Africa. But to put it in perspective across the US mining industry productivity is 4 tons/manhour underground, and 10 tons/manhour surface.

Most modern mining equipment today is relatively inefficient – as an illustration rock is much stronger in compression that under tension, and yet machines work more to induce failure using compressive loading rather than tensile. Thus current EROI calculations, on the energy costs of mining underground, are similarly based on the use of existing mining machines and systems. There are alternatives, and given that a considerable part of the Energy cost is spent in keeping miners alive and safe, the gains from remote mining can be considerable.

As a result of this (and bearing in mind, as the NRC Report noted, that the Government of the moment is not funding mining research at any significant level) it is possible that future developments may lower costs for mining coal, making more of the resource a reserve (for illustrative example only, this might include burning some of the coal in place). A major weakness of both the Rutledge and Energy Watch positions is that they do not recognize some of these issues. The reserves, such as those in Illinois, did not cease to exist when they were downgraded, they just became uneconomic – under the then prevailing conditions. (The coal was higher sulfur and more difficult to sell against the cheap cleaner coal from Wyoming- because of the need for the power station customer to install scrubbers). In both those cases there is an assumption that once the change has been made, it is not reversible.

To illustrate the fallacy of this position, let me convert it to another example. It is the equivalent of saying that when the Saudi Government cut off the flow of oil during and following the 1973 war that this was not reversible, and that, from that point on Saudi oil production could never rise again. (Hint – it did).

I’ve been watching Connections 1 again, and was reminded, watching the episode on “Thunder in the Skies”, which starts by noting that, at the end of the last warming period we had to invent chimneys, and the impact that had on architecture – but then goes on to show the evolution through the Newcomen and Watt engines to Diesel’s machine (with the aid of a scent bottle) and the modern aircraft. The germane part of this is that the Newcomen engine was developed to pump water from mines, and with its evolution what had been an untappable resource of unminable material, suddenly was accessible and a reserve. (And then Stephenson came along and developed the railway and his Blucher (after the Prussian general) which led to the Rocket to get the coal down to the coast).

I thus see two factors making an impact, first, without the investment in a viable alternative, within a few years coal will be the major fossil fuel left, and demand will rise dramatically over the current levels, thereby shortening the life of the existing reserve significantly. And then, secondly, the development of technologies that will allow a greater amount of the resource to be effectively recovered.

For the first to occur investors and companies must be assured that when they make an investment, that this will have a market that will allow them to recover that investment and profit from it. Given the current concerns on Greenhouse gases that is a debatable question, and will likely delay investment. And for the second, someone has to encourage folk to develop those new ideas, and at present they aren’t. Both of which are a pity, since I am not looking forward to repeating the late ‘70’s again but this time without an immediate answer.

So basically future coal production is dependent on relaxing regulatory constraints and new technology to make extraction viable.

Isn't that the oil companies counter to Peak Oil?

Also, you like others talk about "price being high enough" when you obviously mean "profit being high enough". Profit = price - cost. You obliquely address this by saying new technology is needed to reduce costs.

Perhaps at the end of your teaser campaign you eventually will show how CO2 controls will be abandoned, and what the new technology actually is.

The problem with the "high demand = high price" scenario is the same problem with tar sands etc. As the price of energy increases, so do the costs of extraction - the receding horizon.

I'm still baffled why we have a pessimistic view of oil yet such a rosy view of coal. Coal is bad enough as it is, we really don't want any more of it.

Outside of the considerable environmental problems, coal will get a heck of a lot more economic as living standards slide. If you have serfs and slaves at a low standard, they may get by on just bread and tortilias. Sure, they'll die at 50 from black lung, but the upper 1% of the population will continue their lifestyles, which the Bush/Cheney crowd reminds us are not negotiable.

As I commented in an earlier post, the Scientific dept of the UK National Coal Board under Dr "Fritz" Scumacher , of the book "Small is Beautiful", was arguing in the early 1960s that the era of plentiful, cheap oil would be very short - about 40 more years. Since, in his view, there were only two primary products - energy and food, it was strategically most important for the UK to conserve its only secure energy supply - coal. Now that we are more aware of Global Warming it is clear that we must find ways of burning coal without huge Carbon dioxide emmissions. Such methods exist including underground gasification.

If we are talking rationally, I see no reason for not accepting peak oil as a geological fact for the current years. But "peak coal" is not a "geological fact". There are lots of coal reserves: the question is whether it is "economic" to mine them. The answer is surely that when oil becomes very,very expensive then coal becomes "economic" again. This is logical. Even with wholly mechanised longwall mining, electricity cost is a very small part of the coal mining cost structure. There is no net energy return issue.

In the UK the issue is highly political because the Tweedledoms and Tweedledees of UK political parties do not want to admit that the National Coal Board and the National Union of Mineworkers were correct.

RedBaron,

Would you say that by closing all the mines and thus leaving the coal in the ground for future generations (post cheap oil) Margaret Thatcher was securing the UKs coal resources?

This was perhaps not the route that the NCB and NUM would have taken...

Nick.

Its hard to tell if this was the intent but it seems this may have been the outcome.

On the contrary. When you close a colliery, the underground roadways collapse. There is no longer a route between the shaft and the workable seams. This coal is probably sterilised forever. Thatcher's energy policy, like her economic policy, was vandalism based on the belief that wet pavements cause rain.

Red Baron:

The stability of the mine after it is abandoned is controlled by a lot of different factors - including whether or not the mine then floods. There have been mines that have been re-entered years later that are still stable. Caves are an illustration that openings can stay stable without human intervention. In large measure it depends on how large the pillars are when the mine is abandoned. In areas that have been longwalled the roof has collapsed already, and those areas cannot realistically normally be revisited (though they can if you are doing multi-pass extraction and had filled the empty space with waste - though this is quite rare). It also depends on the ways in which they held up the rock over the roadways,

UK colliers were entirely longwall and roadways were supported by steel arches. The earth moves and if buckled arches are not replaced the roadway roof falls preventing access to the coal reserves. Now one one need to sink a new shaft , say 3 years, and you cannot speed this up with a Chinese army approach because there is only a few square meters to work in. Then lower roadway supports and blast out roadways underground. Everything is sequential and takes about 9-10 years if you have a skilled workforce -which the UK has lost. So now the UK faces "peak oil" with no secure alternatives. Short the Pound sterling too.

Bob:

Firstly my apologies for not replying earlier, I really wasn't reading Harry Potter, but involved in a project that took my day.

I believe, if you go back over what I have written in the past you will find that I have spoken out several times about the need to have and enforce strong regulation of the coal industry. What I was trying to point out was that the apparent assumptions that we are running out of actual coal in the ground are using a definition of reserve that is transient and does not reflect the amount of coal that remains, and further that, as other fuels become more expensive to produce, so the definition of what is a coal reserve will likely expand again.

This will likely be more controlled by the economics of demand than new technology, but, and I used in-situ combustion only illustratively of this, new technologies or the improvement of old ones will also play a part in increasing what the reserves of the future are considered to be.

After reviewing recent information and other information over the past several years, I can't help but feeling that there is a major disappointment ahead for those who think that the future will involve dramatic increases in coal production. Production may be stable or rise gently, but perhaps that's about it. The United States, supposedly the "Saudi Arabia of Coal," is close to becoming a net importer of coal! One major obstacle to increasing production is laying enough rail to do so. Present coal-bearing railways are about maxed out. Efforts to put in modest new feeder lines -- in places like Wyoming -- have not been very successful. Proposals to put in a new coal line in a coastal region are laughed at. That could change, but that process of change and eventual construction could take a couple decades.

Also, unlike oil or gas, coal varies widely in quality. On a contained-energy basis, I believe it was noted that the US hit a peak of production in 1998, with lower quality cancelling out any production volume increases since then.

I've seen some estimates of eletricity "demand" that show a doubling by 2030. Makes sense if a lot of Indians and Chinese want to use electricity. This 100% expansion is expected to be provided primarily by coal and nuclear. If 50% of the expansion is provided by coal (reasonable), then world coal production would have to double. If the US is maxed out, and China will be maxed out by 2015 or so, where is this doubling going to come from?

Lastly, as the UK example shows, these coal resource estimates might turn out to be something like a fiction.

When I see maps such as the one above, and for renewable energy resources such as solar and wind, I am always struck by the east-west divide. Two regions, separated by a north-south strip a few hundred miles wide that is marginally habitable (and likely to be less so as GW decreases precipitation and the fossil aquifers are drained). I have to wonder how long it will be before the interests of the two regions diverge, perhaps sharply so.

Econ guy:

As I tried to show from the earlier surveys, there is actually some fairly reliable data on the size of the UK resource. The problem is confusing what is there (the resource) with what is economically and viably recoverable (the reserve). At present the economics are such that deep mined coal cannot compete with oil and gas as a fuel. As those fuels start down the back slope of the production curve coal is, in the short term, a likely replacement - because there already is an industry, it can be geared up, and for a number of uses equipment is already in place to use it. There are some technical and economic issues with using it in machines (such as cars) that use liquid fuels, but these routes (such as CTL) have been developed. Thus it is probable that more of the resource will again be considered as a reserve - which it is currently not. But it is the change in what is considered a reserve that has occured, not the overall size of the resource.

Time for another site: The Coal Bucket

Bravo, Heading Out on this report. Sometimes it seems that TOD participants want fossil fuels to peak more than they want to know if fossil fuels are peaking.

Kinda understand them. I mean, if there is really a lot of coal out there, it won't matter much if we just scream that PV's are better or smth. We'll just dig it up and use it till we frig up our planet big time, more than we've already have.

Yes. Let us please haul up to the surface of the earth the remainder of the sequestered carbon stored since the Eocene. That is BRILLIANT!

As we all know Global Warming is a crock and therefore we can burn all the coal we want with impunity. Don't even mention the pollution or the destruction of entire ecosystems. That is a bunch of liberal hooey anyway.

Just remember the engineer's motto: Don't matter if it kills us all. What matters is that we can do it!!!

Non sequitur - there is a vast difference between acknowledging that global coal reserves are very large and arguing that there should be no constraints on exploiting them.

Yeah, but if we keep it quiet, perhaps they won't notice it and won't dig it ;) lol

I know, Cherenkov, it's all madness isn't it?

So it Goes...

While we're talkin' Coal, I'll once again plug "Big Coal" - Jeff Goodell. Great read. My favorite fun fact: a power plant burns up a mile-long train of coal every twelve hours. Yeah, that's real sustainable!

Well, rabbits, I left my copy at the office and so can't immediately look up

those numbers, so I did a quick google, and found that a typical unit train contains 110 rail cars, and carries 11,000 tons of coal.

Again googling I found that the Longannet Power Station which is considered to be relatively large uses 10,000 tons a day to generate some 2,400 MW of power - so I suspect that the power station using more than twice this much must be one of the larger ones in the United States.

And I would suspect that many of the folk that enjoy the uses of that power aren't aware of where it comes from. But, nevertheless, would be loath to lose it.

As long as the consequences are somewhat remote, people will burn coal. If there is a choice between preventing freezing/ starvation today and higher sea levels tomorrow, people will choose the approach that solves the current problem. They will rationalize that everyone else is doing it, and in fact, everyone else will be doing it. Not good!

Spot on. And that's why it is so important to know with some certainty what coal reserves actually are.

Right now I'd bet on several new deep coal mines being opened in the UK before we hear news of direct solar power plant being built in Algeria.

Coal mines in England provide feed stock for existing generating infrastructure, provide jobs for immigrant east european miners who will pay tax to pay the pensions of our ageing population and the source of the energy lies within our borders.

If only it would stop raining!

I once did some calculations on Coal and global warming for RealClimate, which I'd kept them..

The first assumption was that all Oil and Gas were extracted and burnt, and that 50% of the CO2 remained in the atmosphere.

This gives a surprisingly small final CO2 content (circa 450ppm IIRC). Which is around the somewhat vague limit for acceptable climate change.

From then on it depends entirely on estimates of remaining Coal. The lowest estimates (i.e. peak coal 2020 or so!) give a final CO2 concentration of circa 550-600ppm.

The highest estimates give a concentration circa 2000ppm. Goodbye entire Antartic Ice sheet. 70-100m sea level rise. Not good.

Yet this post indicates that I could well have been wrong about maximum resource sizes. So that figure could end up higher...

Just to let you know, the rock face failure would be from tensile forces. The compressive forces can create a tensile strain at a boundary in the rock, and at this location the rock will fail in tension.

Same with ceramics/concrete, they all normally fail in tension(point loads cause compression on the outer surface, but tension on the back surface, where failure starts)!

Gilgamesh:

Grin, well I don't want to be too argumentative on this but most coal is now mined by picks on shearers and continuous miners, at least underground. The pick is pressed into the solid coal face ahead of the machine - coal that is confined on all but the machine side by surrounding material. As the pick presses into the rock/coal it crushes the immediate material under the point generating a plastic zone that distributes the load and inducing a variety of failure modes from that.

Perhaps I should have included uniaxial before tensile, because the rock is actually stronger under the confining conditions I just described, where it is hard to generate simple tension. The spalling of the back surface of a target is usually only seen at higher dynamic loading conditions than these.

Thanks for a very fine post!

I agree that there will be a lot of interest in coal once it becomes clear oil is a problem, and natural gas (at least in North America) is not a whole lot better.

How much do you see railroads being a bottleneck in increased production? At a minimum, we would need to build a lot of new rail cars and double-track quite a bit of existing tracks.

My hope is that wind will take care of electrical generation demand growth, and that plug-in hybrids will be the main strategy for dealing with liquid fuels.

I think CTL will definitely grow, but maybe not as much as we fear. I think private investment will be fairly large, but not massive, as CO2 concerns will prevent public subsidies.

For better or worse, I don't think railroad capacity will be that large a bottleneck, as coal demand growth depends on pretty large projects: coal generating plants and CTL plants are pretty big, and will take longer to build than rail capacity.

Rail and port capacity have been major bottle necks for Australian coal exports in recent years - compounded by the need to export iron ore, copper, uranium and merlot.

Thanks, Gail:

In regard to the railway bottleneck it is a little hard to predict. Part of the reason for the growth of production from the Powder River Basin was that it was a cleaner coal than the higher calorific value coals from further East and thus power stations did not have to install expensive scrubbers to deal with some of the pollutants. As more power stations install this equipment (and perhaps the ammonia scrubbers that also remove the carbon dioxide from the flue gases) then the rationale for dragging the coal across the country may diminish (see the Prairie State Energy Campus story ). Large (this one will be 1,600 MW) locally fed plants such as this will lower the need for rail. But right now you are right to note that rail is a potentially limiting factor.

Say it slowly: Ten Trillion Tons.

That would burn to around 35 trillion tons of CO2, which is 0.7% of the mass of the entire atmosphere!

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Earth's_atmosphere

Maybe an early collapse is preferable, from the standpoint of the biosphere, to the catabolic calamity of complete coal cache combustion.

either way, doesn't sound good.

I would be very surprised if we are actually able to back transition to coal. I think the time scales are just as much of a problem for coal as it is for electrification of transportation. And at least in the case of coal the people making the decision post collapse will I suspect say enough is enough.

Coal faces the same problems that any transition does just because its worse for the environment does not make it significantly easier than our other choices.

With that said we probably will see a significant increase in coal fired plants short term and this is a big maybe. But I don't see CTL as anymore viable than bio based liquid fuels.

The powers that be that don't want to acknowledge peak oil are also not in a position to push for a big switch to coal for all the same reasons. In this case the Iron Triangle may save us from a worse fate.

http://arctic.atmos.uiuc.edu/cryosphere/

James Burke's Connections is truly a masterpiece. The premiere episode is available on youtube (I trust with the author's permission):

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pTbCNycm0nQ

Cheers,

Paul

Hi, HO.

Current conditions can, or can not change, depending on one's closely held point of view! This is a "selection bias" fallacy.When I am about to succumb to this emotionally-laden position, and can recognize it as such, I stop what I am doing and think about the possible bias in my own thinking. This often rights the ship and I can try to be objective again, knowing that true objectivity can only come in a large group of independent researchers all devoted to scientific modes of thinking. All these arguments will be self-correcting in time. Unfortunately, time is not our side, contrary to what the Rolling Stones sang.

Hope you are well —

Dave

Hi, Dave, good to hear from you again.

I don't think I am being biased to note that conditions are changing and can be anticipated to change further. Rather to deny that would be unrealistic, rather than unemotional. Coal demand is increasing already and with increased demand there is usually a price increase etc etc

Energy costs are also a part of the decision on reserve estimation, but since different ways of mining have different values it is hard to predict how this will impact project viability.

Hope to see you ere long

HO

Heading Out,

Thank you for your post. You might consider if cause and effect are reversed for the collapse of Pennsylvania anthracite that you mention. Anthracite peaked at 90Mt in 1917. In 1958, the year before the Wilkes-Barre disaster, production was 19Mt, so the industry had already collapsed. As you know, the disaster was caused by knowingly mining too close to the Susquehanna River. I think it more likely that the collapse of the industry contributed to the disaster, rather than the other way around.

DaveR:

You may very well be right, since I am not as well informed about the area as perhaps I should be. My opinion was, however in part, formed after talking with the local Congressman about the issue, some years ago.

HO - Big Grinnnn - since when were Scotland and Wales a part of England?

I think I am now slightly less confused about coal than U. In your judgement, is it fair to say that at 1971 / 74 levels we had an ROP of around 197 years for coal?

It's then important to point out that global consumption in 2006 was 6195 million tonnes (are you working in tons or tonnes and does it matter?) so at 2006 consumption levels the ROP has dropped to 95 years.

Faced with falling oil production and likely falling nat gas production it is easy to see coal production escalating and that ROP getting chewed.

Would you care to comment on when you see peak coal production?

As far as reserves are concerned. Deep mining seams about 1 foot thick sounds a bit desperate to me. Offsetting that, I wonder what exploration potential remains - though the risks of predicting / finding coal are way lower than for oil and gas.

WRT the environment - I just don't see CO2 sequestration happening - if we're lucky we may see SO2 scrubbers in the UK.

Getting accurate, objective, realistic figures for global coal reserves should be pretty high on the agendas of the national and international energy agencies right now. Massive consequenes for both energy depletion and climate change models! On a very selfish personal note, I'd rather run the gauntlet of 22 nd century climate change than early 21st century energy depletion - Olduvai and all that.

Surely burning up the remaining coal as quickly as we can with no sequestration is at best putting off devastating economic collapse by 50 years at best. I don't know how old you are, but from my personal "selfish" point of view, I want to be confident that my 2-yo son has a good chance of living a healthy life, and is able to reproduce. After all, my life isn't going to be much affected either way (the effects of climate change I am going to witness in my life are largely due to GHG emissions that have already happened, or will happen before sequestration is widely adopted, or coal production cut back in deference to alternative forms of energy).

I don't think anyone has done the sums yet to work out the consequences of burning more coal in an oil and then gas depleting world economy. My own feeling is that when the realities of energy depletion begin to bite then all talk of climate conservation will disappear. And it is just talk.

My boys are 17 and 14 and right now I am somewhat more concerned about the remote prospect of conscription returning to the UK than rising sea levels next century.

The more immediate threat of a global famine is another matter.

I believe that peak oil may focus world leaders' attention on the realities of energy depletion that will lead to massive investment in non-fossil solar alternatives. Coal may provide the energy bridge that will enable that to happen.

Oh, jings! They are going to de-kilt me in the middle of the High Street. No excuse, - sorry All !

Part of the problem in trying to establish what is a reserve lies in the relative economics of extraction (which was were I was going with some of my earlier posts on this topic) Coal is already seeing a resurgence which I would expect will continue, and expand. As the NRC report noted the definition of reserve lies within a short distance of a known (as in drilled) volume. Coal did not migrate as oil and gas did, so relatively large areal coverage is common, and there is no need for detailed drilling (in most cases) until the site is ready for development. So from that point of view the available amount when it needs to be mined will likely turn out to be more than the currently reported reserve. In many cases it is quite likely that projections will prove out, more likely than for oil. But there hasn't in many countries been the need. Now, in places like Africa and Asia that need is becoming apparent, and so they are going looking, and finding.

The technology for carbon dioxide capture is known and (depending on which side you are on) not that expensive - the cost comes in doing something with it after it is collected. I don't see folk being willing to pay the price, but that may change after next year's election.

Given that we can run the same gauntlet of energy depletion with uranium and save the climate, why even look at coal? The climate change in the 22nd century will be enormously worse.

2000 ppm CO2? Humans will have trouble thinking and just staying awake at that level. "outdoor fresh air" will be as stuffy as the worst conference room today. Inside will be literally toxic---people will regularly die from other people's breath. How will we manage intelligent remediation? Imagine how dumb the masses are now.

Carbon sequestration == permanently unmined coal.

1) Rutledge shows UK coal reserves being approx. constant until approx. 1980, at which time they collapse dramatically. What happened in 1980 to change the economics of coal mining? If nothing happened then, perhaps the cause of the reserve collapse is, as Rutledge suggest, a non-ecomonic, bureaucratic muddle.

2) Rutledge shows an Hubbert linearization for China coal. China coal cannot be declining in production because of an serious increased availability of low cost oil to China.

I'm puzzled.

Not sure about 1980, but in 1984, there was a major miners' strike (mainly over proposed pit closures).

Glossing over the political overtones (about how the UK Government used the strike to break the power of all trade unions), the result was still that closures happened, as the production was not subsidised like in most other European countries, and hence became uneconomic; coal imports from Poland (which not onlyhad lower labour costs, but also subsidised production) and other countries meant that, even though the UK production was more efficient (greater productivity per miner), it still cost more.

(http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/links/doi/10.1111/1467-8543.00048)

AKH

Heading Out,

I think that the simplest way to interpret the table showing the 1952 UK reserves as 46Gt is that it is just wrong. Much of this should not have been counted as reserves at that time. Only 6.5Gt has been produced since then, with a current trend to an additional 200Mt. If we had fitted a normal curve to earlier production at the time, we would have predicted further production of 5.5Gt, which is close the actual result. The later production would not have been a surprise if the planners had been fitting normal curves to previous production rather than relying on geology surveys.

Dave - I gotta say I'm very very sceptical about using a top down depletion analysis of UK coal where production has been influenced by Winston Chrchill's decision to convert the Royal Navy to run on oil, two world wars, nationalisation of the industry, a major strike followed by privatisation of a fragmented industry that was forced to compete in a global market that had been newly globalised.

Give me a bottom up analysis of coal in the ground any day combined with a realistic assessment of what may be recovered under both economic competitive conditions and under eroei competitive conditions.

Dave,

Are there any countries that are more depleted than the UK? (I know that would be difficult)? What I am getting at here is that it would be nice to have an example of a country that hit the bottom of the HL graph, and had stopped mining coal 10 or 20 years ago. Some kind of case where it would be very hard to argue that politics ended the curve early. And that would lend some support to the idea that HL works on coal, and thus works in the UK. (I know, the UK was your example, they just are not buying it).

Jon Freise

Analyze Not Fantasize -D. Meadows

Hi GTrout,

Thanks for your suggestion.

This plot is for UK coal, and it is a comparison of predictions of the ultimate production over time by two different methods. For the first, I add the reserves reported to the World Energy Council to the cumulative production. For the second we fit a cumulative normal curve to the cumulative production. It is an estimate that only uses information that was available at that time, so it could have been done then. Before 1880, the fit does not converge, and Hull's 1864 reserves are the only estimate of the ultimate. However, after about 1880, the normal fit begins to pick up something, and it is within a factor of two from that time on. From 1926 on, the fit is extremely good, with an error of 4% or better. In contrast, as an estimate of the ultimate production, the reserves are terrible.

This is the same kind of plot for PA anthracite, and the story is similar. The cumulative fit starts to get the range around 1890, and there is a maximum of 50% error after this time. Again, the error in estimating ultimate production from reserves is huge. I have one appropriate reserve number, from 1913, and it corresponds to an ultimate that is 4 times too high.

You might have more luck with some of the smaller European countries - thinking of places such as Belgium, or parts of France, but I don't know enough about their history to be sure that they closed because of lack of resource, rather than other economic factors.

Hi Heading Out,

Oops, typo, should have been 6% for the maximum error in the fit for UK ultimate production in each year from 1926 on, not 4%.

You want better than 6% error? Aren't you setting the bar pretty high?

I think that it is remarkable that a simple fit of a normal to cumulative production data gives you the ultimate UK production accurately, before WWII, nationalization, Margaret Thatcher, North Sea oil and gas, mechanization in coal mines, and Indonesian coal. The same could be said for Pennsylvania anthracite. Conceptually this is as simple a mathematical procedure as one could imagine for predicting the ultimate, and it works. The reason it works is that the cumulative production for UK coal and Pennsylvania anthracite is pretty close to a single normal curve.

All coal mines shut down for economic reasons, and they all leave coal resources in the ground, just as all oil fields shut down for economic reasons, and they all leave oil resources in the ground. No country has exhausted its resources, but they can exhaust their reserves.

Dave:

I don't think that we are disagreeing with each other, except only in that you seem to be assuming that once a resource (coal seam) is removed from the reserve base, then it can't be put back. My intended point was that, with circumstances likely to change, there is enough coal in the ground as a resource that it could be converted into a reserve through either technology or ecconomics in the future. And secondly that there is a likelihood that such a transition back will occur - and this is the debatable part of the issue. But given that there has been the impression given that the coal that is no longer a reserve has gone away, I felt it valuable to point out that it is, in fact and in large measure, still there.

Heading out,

Thanks for your comments. There is coal still down there. The question is whether an industry that has fallen as far as UK coal, and is falling as fast as UK coal, is going to recover production to a significant level, say 100Mt per year? Underground production in the last quarter is running at 2% of the peak 1913 production rate, with a drop of 40% from the same quarter the previous year. We need to consider also that the post-war expansion, mechanization, and nationalization, were not sufficient forces to push UK coal production appreciably above the cumulative normal production curve that goes back to the 1800's. What would do it now? The major coal exporters, Australia, Columbia, Russia, and Indonesia are all expanding production. The UK is likely to be able to import coal at prices that are significantly better on energy basis than oil and gas for decades. France shut down its last mine, in 2004, and Germany has announced plans to shut down the last West German mines by 2018.

DaveR:

Sorry but I have to disagree. Apart from the relatively reliable sources on which that projection was made, you are missing the point. Back in 1952 there was no North Sea oil, and most coal was won by men with picks working on longwall faces with coal being blasted from the face by black powder. Mechanization had not arrived, and Europe was still desperate for fuel after the Second World War. Thus, in large measure, if you could mine it, you could sell it.

As Euan noted the situation has changed much since then, and the price of competing fuels (oil and natural gas particularly) have made it currently uneconomic to mine many of these seams, and thus they cannot currently be considered as reserves - by definition. But they have not gone away, and as alternative fuel prices go up, so the practicality of mining some of them will return. The burgeoning coal industry in China is mining coal that was not viable ten years ago, but for which there is now a market.

In Chris Vernon’s post “Coal - The Roundup” earlier this month (TOD Europe) he referenced (as no. 3) the report “Coal of the Future, a study by B. Kavalov of the Institute for Energy (IFE), prepared for European Commission Joint Research Centre”. In section 4.4.1 on page 34 of this report it notes that some 600Bt of coal that can be accessed by underground coal gasification (UCG), representing an increase in coal reserves of 66%.

The report also goes on to state:

“If UCG is employed to produce gas, the resource may exceed natural gas resources. The total volume gas available from the estimated UCG reserves for the leading countries studied is 6,900 Tcf (194 Tcm). This compares with a proven world gas reserve (BP statistical review 2006) of 6,300 Tcf (180 Tcm).”

The potential of UCG to release CO2 into the atmosphere does not look good from a climate change perspective, especially as the economics of UCG look to be close to being competitive now. Carbon capture and storage does look to be more feasible with UCG though.

Carbon capture and storage does look to be more feasible with UCG though Well a huge problem will be finding another rock formation in which to store the CO2 ie a different horizon within the same coal basin or another formation some distance away. Note the CO2 will come from both the partly combusted underground gas and the above ground application. This makes me think that the potential for UCG is way overstated unless they are fibbing (oh no!) about carbon capture.

I don't have data but I think the misguided carbon credit for methane burning may affect the economics of UCG. Misguided since the best option must be to leave all carbon underground. Since politicians are incapable of bringing in meaningful carbon limits perhaps our only hope is Export Land type conservation as coal reserves visibly dwindle.

Nik G:

The technological difficulties in getting UCG to work reliably and consistently have perhaps been underestimated. There is some work ongoing on this, and I have posted on it before - the syngas that comes to the surface is largely hydrogen and carbon monoxide as I remember, so it will be somewhat cleaner that burning at the surface and, as I noted above, there are methods for stripping the CO2 from the products, and perhaps that could be injected into burned out areas (the overlying rock will have been baked to brick. It is usually a shale that is good for brick making).

PNM electric apparently plans to address fuel for electricity generation.

I'm thinking about all of the diesel used to produce and transport coal. EROEI?

While trying to send some crooked judges to jail, of course.

The industrial revolution and industrial civilisation would not have happened had coal not had a very high ERoEI.

Imagine a steam train with 50 full coal trucks in tow. How much of that coal is used to drag the load a 1000 kms?

What we need is a process of converting coal directly into hydrogen and carbon nanotubes to build super conducting power lines :P

Lets not forget the problems of mercury and other heavy metal and sometimes radioactive components of coal, not to mention the deaths & environmental devestation caused by mining.

Our geological processes have been very succesful at changing the environment along with solar cycles and changes in the planets inhabitants. Sequesting billions of tons of CO2 in coal was a smart was to stabilise the environment, lets not mess with the PH of the ocean and its system of microscopic life that has a huge effect on the higher ends of the food chain, they are already over fished and polluted give them a bit of a chance. But hey no worries CTL means we can run our mining equipment and trains on the coal which they provide us with :) everyones a winner!! We could use those 50MWh NaS batteries in mass production any time soon

http://www.electricitystorage.org/tech/technologies_technologies_nas.htm

I was looking at the relative size of coal consumption vs oil consumption, (in BOEs) based on 2006 data shown in the BP 2007 report.

Worldwide, coal consumption is just under 80% of oil consumption, but this varies a lot by country. China of course has very high coal consumption, with a ratio of 341%. The ratio for the US is 60%, and for UK, 53%. I had expected the ratio for the UK to be lower, but I suppose it imports quite a bit.

It seemed to me that if coal was high in relationship to oil production (and produced at home), it would be easier to scale up to offset the declining oil availability.

Gail:

It takes a lot longer to get a coal mine permitted and everything operating that it does with an oilwell. At a minimum it is likely to be around 7 years and can easily extend beyond 10. Production increases are more likely to come from existing operations, where the general size of reserves are such that, where the market develops, it doesn't cost too much to activate another section.

On the surface you would, however, have to find a reliable source of new tires before you could increase production much, and they are still hard to find.

Well, time for a little Harry Potter I think. G'night.

Underground Coal Gasification is a way extract energy from deep seams. The product is syngas that can also be used for F-T liquification.

The are now many companies investigating this technology. Linc Energy is one of them.

HO, I’m sorry for this late comment, but I just had time to read this interesting piece now.

Once again you made clear that the term “Coal Reserves” is a hazy one, and that we shouldn’t consider the latest bearish assessments written in stone. We must take in deep consideration a new Coal cycle emerging in the wake of some technological breakthrough, like in-situ gasification.

There’s another question to answer though, how much can a new Coal cycle impact the not-too distant peak some of us see forming in the horizon. Or asking it the other way round, could we have gone over 3000 Mtoe/a solely on “men with picks”?

Can we keep on with these extraction rates with less energy intensive technologies?

Luis:

There are some simple tools that have been used in the past that can be applied again - things such as coal plows, or, in the right conditions, underground hydraulic mining (the most productive, and safest, mine in Canada in the 1970's was a hydraulic mine at Sparwood). But to develop new ideas and technologies you need people and a research program, and as the recent NRC report pointed out there has been little investment in either over the past decade.

My understanding is that there are 30 coal trains a day that pass through Denver from the Powder River Basion to Texas power stations. With a typical train of 120 cars, you will often see a train parked at a siginal for over a day, waiting to enter the next southbound signal block. My guess is that the rail trafic southbound out of Denver is running at capacity for this part of the rail system

It seems to me in situ gasification is in some ways the reverse of capture and underground storage. I detect an inconsistency in that UCG advocates assure us the useful gas will happily migrate to the surface while CCS advocates assure us that the nasty gas will stay safely below ground. Somehow I feel that UCG will make the same kind of progress we see in cellulosic ethanol and oil from algae, not.

Offshore oil was not economic to mine till we developed the technology. So for coal. When we need to mine coal by robot under the water table, we will. The coal will be more expensive, just as offshore oil was more expensive than onshore oil, but it will be available.

The more important question is whether we should.