Herman Daly: Towards A Steady-State Economy

Posted by nate hagens on May 5, 2008 - 9:21am

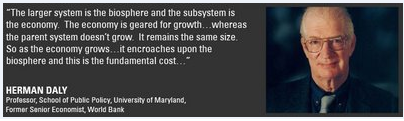

It is doubtful we can adequately inform energy policy without addressing the linkages between equity, the environment, finance, and our end goals. I post this on theoildrum not only because Herman is one of my tribal elders but because his eloquence, courage and foresight on these issues have historically been, and continue to be, ahead of the curve. During his resignation speech from the World Bank, Herman recommended the Bank take "a few antacids and laxatives to cure the combination of managerial flatulence and organizational constipation giving rise to such a high-pressure internal environment." To improve interactions with the external world he prescribed "new eyeglasses and a hearing aid."

Nearly 15 years later, here is Professor Daly's current synopsis of the state of economics and his prescriptions for change.

Sustainable Development Commission, UK (April 24, 2008)

A Steady-State Economy

(Editors note: underlined words are in original; bold, italicized, hyperlinks and images added)

A failed growth economy and a steady-state economy are not the same

thing; they are the very different alternatives we face.

The Earth as a whole is approximately a steady state. Neither the

surface nor the mass of the earth is growing or shrinking; the inflow of

radiant energy to the Earth is equal to the outflow; and material imports

from space are roughly equal to exports (both negligible). None of this

means that the earth is static—a great deal of qualitative change can

happen inside a steady state, and certainly has happened on Earth. The

most important change in recent times has been the enormous growth of

one subsystem of the Earth, namely the economy, relative to the total

system, the ecosphere. This huge shift from an “empty” to a “full” world

is truly “something new under the sun” as historian J. R. McNeil calls it in

his book of that title. The closer the economy approaches the scale of the

whole Earth the more it will have to conform to the physical behavior

mode of the Earth. That behavior mode is a steady state—a system that

permits qualitative development but not aggregate quantitative growth.

Growth is more of the same stuff; development is the same amount of

better stuff (or at least different stuff). The remaining natural world no

longer is able to provide the sources and sinks for the metabolic

throughput necessary to sustain the existing oversized economy—much

less a growing one.

Economists have focused too much on the economy’s

circulatory system and have neglected to study its digestive tract.

Throughput growth means pushing more of the same food through an

ever larger digestive tract; development means eating better food and

digesting it more thoroughly. Clearly the economy must conform to the

rules of a steady state—seek qualitative development, but stop

aggregate quantitative growth. GDP increase conflates these two very

different things.

We have lived for 200 years in a growth economy. That makes it

hard to imagine what a steady-state economy (SSE) would be like, even

though for most of our history mankind has lived in an economy in which

annual growth was negligible. Some think a SSE would mean freezing in

the dark under communist tyranny. Some say that huge improvements in

technology (energy efficiency, recycling) are so easy that it will make the

adjustment both profitable and fun.

Regardless of whether it will be hard or easy we have to attempt a

SSE because we cannot continue growing, and in fact so-called

“economic” growth already has become uneconomic. The growth

economy is failing. In other words, the quantitative expansion of the

economic subsystem increases environmental and social costs faster than

production benefits, making us poorer not richer, at least in high consumption

countries. Given the laws of diminishing marginal utility and

increasing marginal costs this should not have been unexpected. And

even new technology sometimes makes it worse. For example, tetraethyl

lead provided the benefit of reducing engine knock, but at the cost

spreading a toxic heavy metal into the biosphere; chlorofluorocarbons

gave us the benefit of a nontoxic propellant and refrigerant, but at the

cost of creating a hole in the ozone layer and a resulting increase in

ultraviolet radiation. It is hard to know for sure that growth now increases

costs faster than benefits since we do not bother to separate costs from

benefits in our national accounts. Instead we lump them together as

“activity” in the calculation of GDP.

Ecological economists have offered empirical evidence that growth

is already uneconomic in high consumption countries (see ISEW, GPI,

Ecological Footprint, Happy Planet Index). Since neoclassical economists

are unable to demonstrate that growth, either in throughput or GDP, is

currently making us better off rather than worse off, it is blind arrogance

on their part to continue preaching aggregate growth as the solution to

our problems. Yes, most of our problems (poverty, unemployment,

environmental degradation) would be easier to solve if we were richer--

that is not the issue. The issue is: Does growth in GDP any longer really

make us richer? Or is it now making us poorer?

The classical steady state takes the biophysical dimensions—

population and capital stock (all durable producer and consumer goods)—

as given and adapts technology and tastes to these objective conditions.

The neoclassical “steady state” (proportional growth of capital stock and

population) takes tastes and technology as given and adapts by growth in

biophysical dimensions, since it considers wants as unlimited, and

technology as powerful enough to make the world effectively infinite. At a

more profound level the classical view is that man is a creature who must

ultimately adapt to the limits (finitude, entropy, ecological

interdependence) of the Creation of which he is a part. The neoclassical

view is that man, the creator, will surpass all limits and remake Creation to

suit his subjective individualistic preferences, which are considered the

root of all value. In the end economics is religion.

Accepting the necessity of a SSE, along with John Stuart Mill and

the other classical economists, let us imagine what it might look like. First

a caution—a steady-state economy is not a failed growth economy. An

airplane is designed for forward motion. If it tries to hover it crashes. It is

not fruitful to conceive of a helicopter as an airplane that fails to move

forward. It is a different thing designed to hover. Likewise a SSE is not

designed to grow.

Following Mill we might define a SSE as an economy with constant

population and constant stock of capital, maintained by a low rate of

throughput that is within the regenerative and assimilative capacities of

the ecosystem. This means low birth equal to low death rates, and low

production equal to low depreciation rates. Low throughput means high

life expectancy for people and high durability for goods. Alternatively, and

more operationally, we might define the SSE in terms of a constant flow

of throughput at a sustainable (low) level, with population and capital

stock free to adjust to whatever size can be maintained by the constant

throughput that begins with depletion of low-entropy resources and ends

with pollution by high-entropy wastes.

How could we limit throughput, and thus indirectly limit stocks of

capital and people in a SSE? Since depletion is spatially more

concentrated than pollution the main controls should be at the depletion

or input end. Raising resource prices at the depletion end will indirectly

limit pollution, and force greater efficiency at all upstream stages of

production. A cap-auction-trade system for depletion of basic resources,

especially fossil fuels, could accomplish a lot, as could ecological tax

reform, about which more later.

If we must stop aggregate growth because it is uneconomic, then

how do we deal with poverty in the SSE? The simple answer is by

redistribution—by limits to the range of permissible inequality, by a

minimum income and a maximum income. What is the proper range of

inequality—one that rewards real differences and contributions rather

than just multiplying privilege? Plato thought it was a factor of four.

Universities, civil services and the military seem to manage with a factor

of ten to twenty. In the US corporate sector it is over 500. As a first step

could we not try to lower the overall range to a factor of, say, one

hundred? Remember, we are no longer trying to provide massive

incentives to stimulate (uneconomic) growth! Also, since we are not

trying to stimulate aggregate growth, we no longer need to spend billions

on advertising. Instead of treating advertising as a tax-deductible cost of

production we should tax it heavily as a public nuisance. If economists

really believe that the consumer is sovereign then she should be obeyed

rather than manipulated, cajoled, badgered, and lied to.

Free trade would not be feasible for a SSE, since its producers

would necessarily count many costs to the environment and the future

that foreign firms located in growth economies are allowed to ignore. The

foreign firms would win in competition, not because they were more

efficient, but simply because they did not pay the cost of sustainability.

Regulated international trade under rules that compensated for these

differences (compensating tariffs) could exist, as could “free trade”

among nations that were equally committed to sustainability in their

domestic cost accounting. One might expect the IMF, the World Bank, and

the WTO to be working toward such regulations. Instead they vigorously

push both free trade and free capital mobility (i.e., deregulation of

international commerce). Protecting an efficient national policy of cost

internalization is very different from protecting an inefficient firm.

The case for guaranteed mutual benefit in international trade, and

hence the reason for leaving it “free”, is based on Ricardo’s comparative

advantage argument. A country is supposed to produce the goods that it

can produce more cheaply relative to other goods, than is the case in

other countries. By specializing according to their comparative advantage

both trading partners gain, regardless of absolute costs (one country

could produce all goods more cheaply, but it would still benefit by

specializing in what it produced relatively more cheaply and trading for

other goods). This is logical, but like all logical arguments comparative

advantage is based on premises. The key premise is that while capital

(and other factors) moves freely between industries within a nation, it

does not move between nations. If capital could move abroad it would

have no reason to be content with a mere comparative advantage at

home, but would seek absolute advantage—the absolutely lowest cost of

production anywhere in the world. Why not? With free trade the product

could be sold anywhere in the world, including the nation the capital just

left. While there are certainly global gains from trade under absolute

advantage there is no guarantee of mutual benefit. Some countries could

lose.

The IMF-WB-WTO ( Washington Consensus) contradict themselves in service to the interests

of transnational corporations. International capital mobility, coupled with

free trade, allows corporations to escape from national regulation in the

public interest, playing one nation off against another. Since there is no

global government they are in effect uncontrolled. The nearest thing we

have to a global government (IMF-WB-WTO) has shown no interest in

regulating transnational capital for the common good. Their goal is to help

these corporations grow, because growth is presumed good for all—end

of story. If the IMF wanted to limit international capital mobility to keep

the world safe for comparative advantage, there are several things they

could do. They could promote minimum residence times for foreign

investment to limit capital flight and speculation, and they could propose

a small tax on all foreign exchange transactions (Tobin tax). Most of all

they could revive Keynes’ proposal for an international multilateral

clearing union that would directly penalize persistent imbalances in

current account (both deficit and surplus), and thereby indirectly promote

balance in the compensating capital account, reducing international

capital movements.

One problem for the SSE already raised by the demographic

transition to a non growing population is that it necessarily results in an

increase in the average age of the population—more retirees relative to

workers. Adjustment requires either higher taxes, older retirement age, or

reduced retirement pensions. The system is hardly in “crisis”, but these

adjustments are surely needed to achieve sustainability. For many

countries net immigration has become a larger source of population

growth than natural increase. Immigration may temporarily ease the age

structure problem, but the steady-state population requires that births

plus in-migrants equal deaths plus out-migrants. It is hard to say which is

more politically incorrect, birth limits or immigration limits? Many prefer

denial of arithmetic to facing either one.

The SSE will also require a “demographic transition” in populations

of products towards longer-lived, more durable goods, maintained by

lower rates of throughput. A population of 1000 cars that last 10 years

requires new production of 100 cars per year. If more durable cars are

made to last 20 years then we need new production of only 50 cars per

year. To see the latter as in improvement requires a change in perspective

from emphasizing production as benefit to emphasizing production as a

cost of maintenance. Consider that if we can maintain 1000 cars and the

transportation services thereof by replacing only 50 cars per year rather

than 100 we are surely better off—the same capital stock yielding the

same service with half the throughput. Yet the idea that production is a

maintenance cost to be minimized is strange to most economists. Shifting

taxes from value added to throughput would promote this minimizing

effort. One adaptation in this direction is the service contract that leases

the service of equipment (ranging from carpets to copying machines),

which the lessor/owner maintains, reclaims, and recycles at the end of its

useful life.

Although the main thrust of reforms for the SSE is to bring newly

scarce and truly rival natural capital and services under the market

discipline, we should not overlook the opposite problem, namely, freeing

truly non rival goods from their artificial enclosure by the market. There

are some goods that are by nature non-rival, and should be freed from

illegitimate enclosure by the price system. I refer especially to knowledge.

Knowledge, unlike throughput, is not divided in the sharing, but multiplied.

Once knowledge exists, the opportunity cost of sharing it is zero and its

allocative price should be zero. International development aid should more

and more take the form of freely and actively shared knowledge, along

with small grants, and less and less the form of large interest-bearing

loans. Sharing knowledge costs little, does not create unrepayable debts,

and it increases the productivity of the truly rival and scarce factors of

production. Existing knowledge is the most important input to the

production of new knowledge, and keeping it artificially scarce and

expensive is perverse. Patent monopolies (aka “intellectual property

rights”) should be given for fewer “inventions”, and for fewer years.

What would happen to the interest rate in a SSE? Would it not fall

to zero without growth? Not likely, because capital would still be scarce,

there would still be a positive time preference, and the value of total

production may still increase without growth in physical throughput—as a

result of qualitative development. Investment in qualitative improvement

may yield a value increase out of which interest could be paid. However,

the productivity of capital would surely be less without throughput

growth, so one would expect low interest rates in a SSE, though not a

zero rate.

Would it be possible to have qualitative improvement (e.g.

increasing efficiency) forever, resulting in GDP growth forever? GDP would

become ever less material-intensive. Environmentalists would be happy

because throughput is not growing; economists would be happy because

GDP is growing. I think this should be pushed as far as it will go, but how

far is that likely to be? Consider that sectors of the economy generally

thought to be more qualitative, such as information technology, turn out

on closer inspection to have a substantial physical base, including a

number of toxic metals.

Also, if expansion is to be mainly for the sake of the poor it must

be comprised of goods the poor need—clothing, shelter, and food on the

plate, not ten thousand recipes on the Internet. In addition, as a larger

proportion of GDP becomes less material-intensive, the terms of trade

between more and less material-intensive goods will move against the less

material-intensive, limiting incentive to produce them. Even providers of

information services spend most of their income on cars, houses, and

trips, rather than the immaterial product of other symbol manipulators.

Can a SSE maintain full employment? A tough question, but in

fairness one must also ask if full employment is achievable in a growth

economy driven by free trade, off-shoring practices, easy immigration of

cheap labor, and widespread automation? In a SSE maintenance and repair

become more important. Being more labor intensive than new production

and relatively protected from off-shoring, these services may provide

more employment. Yet a more radical rethinking of how people earn

income may be required. If automation and off-shoring of jobs increase

profits but not wages, then the principle of distributing income through

jobs becomes less tenable. A practical solution (in addition to slowing

automation and off-shoring) may be to have wider participation in the

ownership of businesses, so that individuals earn income through their

share of the business instead of through fulltime employment. Also the

gains from technical progress should be taken in the form of more leisure

rather than more production—a long expected but under-realized

possibility.

What sort of tax system would best fit a SSE? Ecological tax

reform, already mentioned, suggests shifting the tax base away from

value added (income earned by labor and capital), and on to “that to

which value is added”, namely the throughput flow, preferably at the

depletion end (at the mine-mouth or well-head, the point of “severance”

from the ground). Many states have severance taxes. Taxing the origin

and narrowest point in the throughput flow induces more efficient

resource use in production as well as consumption, and facilitates

monitoring and collection. Taxing what we want less of (depletion and

pollution), and ceasing to tax what we want more of (income, value

added) would seem reasonable—as the bumper sticker puts it, “tax bads,

not goods”. The shift could be revenue neutral and gradual. Begin for

example by forgoing $x revenue from the worst income tax we have.

Simultaneously collect $x from the best resource severance tax we could

devise. Next period get rid of the second worst income tax, and

substitute the second best resource tax, etc. Such a policy would raise

resource prices and induce efficiency in resource use. The regressivity of

such a consumption tax could be offset by spending the proceeds

progressively, by the limited range of inequality already mentioned, and

by the fact that the mafia and other former income tax cheaters would

have to pay it. Cap-auction–trade systems will also increase government

revenue, and auction revenue can be distributed progressively.

Could a SSE support the enormous superstructure of finance built

around future growth expectations? Probably not, since interest rates and

growth rates would be low. Investment would be mainly for replacement

and qualitative improvement. There would likely be a healthy shrinkage of

the enormous pyramid of debt that is precariously balanced atop the real

economy, threatening to crash. Additionally the SSE could benefit from a

move away from our fractional reserve banking system toward 100%

reserve requirements.

One hundred percent reserves would put our money supply back

under the control of the government rather than the private banking

sector. Money would be a true public utility, rather than the by-product of

commercial lending and borrowing in pursuit of growth. Under the existing

fractional reserve system the money supply expands during a boom, and

contracts during a slump, reinforcing the cyclical tendency of the

economy. The profit (seigniorage) from creating (at negligible cost) and

being the first to spend new money and receive its full exchange value,

would accrue to the public rather than the private sector. The reserve

requirement, something the Central Bank manipulates anyway, could be

raised from current very low levels gradually to 100%. Commercial banks

would make their income by financial intermediation (lending savers’

money for them) as well as by service charges on checking accounts,

rather than by lending at interest money they create out of nothing.

Lending only money that has actually been saved by someone

reestablishes the classical balance between abstinence and investment.

This extra discipline in lending and borrowing likely would prevent such

debacles as the current “sub-prime mortgage” crisis. 100% reserves

would both stabilize the economy and slow down the Ponzi-like credit

leveraging.

A SSE should not have a system of national income accounts, GDP,

in which nothing is ever subtracted. Ideally we should have two accounts,

one that measures the benefits of physical growth in scale, and one that

measures the costs of that growth. Our policy should be to stop growing

where marginal costs equal marginal benefits. Or if we want to maintain

the single national income concept we should adopt Nobel laureate

economist J. R. Hicks’ concept of income, namely, the maximum amount

that a community can consume in a year, and still be able to produce and

consume the same amount next year. In other words, income is the

maximum that can be consumed while keeping productive capacity

(capital) intact. Any consumption of capital, manmade or natural, must be

subtracted in the calculation of income. Also we must stop the

asymmetry of adding to GDP the production of anti-bads without first

having subtracted the generation of the bads that made the anti-bads

necessary. Note that Hicks’ conception of income is sustainable by

definition. National accounts in a sustainable economy should try to

approximate Hicksian income and abandon GDP. Correcting GDP to

measure income is less ambitious than converting it into a measure of

welfare, discussed earlier.

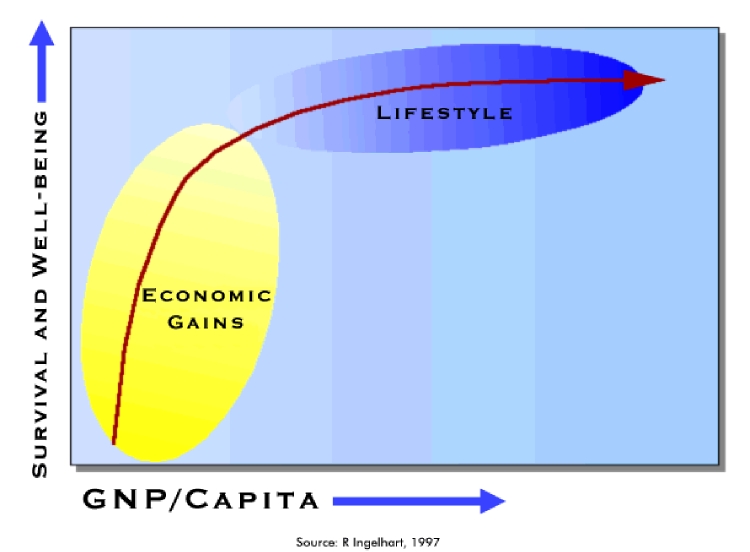

The logic of the SSE is reinforced by the recent finding of

economists and psychologists that the correlation between absolute

income and happiness extends only up to some threshold of “sufficiency,”

and beyond that point only relative income influences self-evaluated

happiness. This result seems to hold both for cross-section data

(comparing rich to poor countries at a given date), and for time series

(comparing a single country before and after significant growth in

income). Growth cannot increase everyone’s relative income. The welfare

gain of people whose relative income increases as a result of further

growth would be offset by the loss of others whose relative income falls.

And if everyone’s income increases proportionally, no one’s relative

income would rise and no one would feel happier. Growth becomes like an

arms race in which the two sides cancel each other’s gains. A happy

corollary is that for societies that have reached sufficiency, moving to a

SSE may cost little in terms of forgone happiness. The “political

impossibility” of a SSE may be less than it previously appeared.

Nevertheless it is one thing to imagine the possibility of a SSE, but

something else to chart a transition thereto from a failed growth

economy. Can one transform an airplane into a helicopter without first

landing, or perhaps crashing? In order even to take such a task seriously

one has to realize that the growth economy is heading for a big crash.

Whether the measures suggested above are sufficient to convert the

growth airplane to a steady-state helicopter is hard to say, but I do think

they are probably necessary, and at a minimum would be useful guides for

reconstruction after the crash. They also may prove capable of being

applied gradually in mid air. For example, a cap-auction-trade system

could begin with a generous cap followed by a gradual pre-announced

schedule of tightening. The limits to income inequality could begin far

apart, and be gradually tightened. Ecological tax reform could substitute

at first only the worst value added taxes by the best throughput taxes, as

mentioned earlier. Compensatory tariffs to protect national costinternalization

policies could be imposed and raised gradually. Reserve

requirements for banks could be raised gradually to one hundred percent.

Patent monopolies could be gradually reduced and knowledge gradually

restored to its proper status as a non rival good. Downsizing of the IMFWB-

WTO from a servant of global integration in the interests of

transnational capitalist growth to something closer to Keynes’ nationbased

multilateral clearing union for international payments—this would

be more difficult to do gradually. But nations may begin individually to

withdraw from these institutions as it becomes more evident that they

have abandoned the federated internationalist nature of their Bretton

Woods Charter in favor of an economically integrated globalist vision of

capital-dominated growth, and are as yet incapable of conceiving the

possibility, much less recognizing the reality, of uneconomic growth.

While these transitional policies will appear radical to many, it is worth remembering that, in addition to being amenable to gradual application, they are based on the conservative institutions of private property and decentralized market allocation. They simply recognize that private property loses its legitimacy if too unequally distributed, and that markets lose their legitimacy if prices do not tell the whole truth about costs. In addition, the macro-economy becomes an absurdity if its scale is structurally required to grow beyond the biophysical limits of the Earth. And well before that radical physical limit we are encountering the conservative economic limit in which extra costs of growth become greater than the extra benefits.

Ten Point Policy Summary

1. Cap-auction-trade systems for basic resources. Cap limits to biophysical scale according to source or sink constraint, whichever is more stringent. Auction captures scarcity rents for equitable redistribution. Trade allows efficient allocation to highest uses.2. Ecological tax reform—shift tax base from value added (labor and capital) and on to “that to which value is added”, namely the entropic throughput of resources extracted from nature (depletion), through the economy, and back to nature (pollution). Internalizes external costs as well as raises revenue more equitably. Prices the scarce but previously unpriced contribution of nature.

3. Limit the range of inequality in income distribution—a minimum income and a maximum income. Without aggregate growth poverty reduction requires redistribution. Complete equality is unfair; unlimited inequality is unfair. Seek fair limits to inequality.

4. Free up the length of the working day, week, and year—allow greater option for leisure or personal work. Full-time external employment for all is hard to provide without growth.

5. Re-regulate international commerce—move away from free trade, free capital mobility and globalization, adopt compensating tariffs to protect efficient national policies of cost internalization from standards-lowering competition from other countries.

6. Downgrade the IMF-WB-WTO to something like Keynes’ plan for a multilateral payments clearing union, charging penalty rates on surplus as well as deficit balances—seek balance on current account, avoid large capital transfers and foreign debts.

7. Move to 100% reserve requirements instead of fractional reserve banking. Put control of money supply and seigniorage in hands of the government rather than private banks.

8. Enclose the remaining commons of rival natural capital in public trusts, and price it, while freeing from private enclosure and prices the non rival commonwealth of knowledge and information. Stop treating the scarce as if it were non scarce, and the non scarce as if it were scarce.

9. Stabilize population. Work toward a balance in which births plus immigrants equals deaths plus out-migrants.

10. Reform national accounts—separate GDP into a cost account and a benefits account. Compare them at the margin, stop growing when marginal costs equal marginal benefits. Never add the two accounts.

Herman E. Daly

School of Public Policy

University of Maryland

College Park MD 20742 USA

(**Editor's Note: the Sustainable Development Commission is a body set up to advise the UK Government on sustainable development. Herman's essay was commissioned as part of their ongoing ‘Redefining Prosperity’ efforts.

This is my first comment - long time lurker here (great site). I don’t know Prof Daly but did meet him once at a conference – a great thinker and from what I've heard a gracious man.

The above piece is good, and about as far as one can go without getting too politically uncomfortable. It’s logical and methodical which is probably why it won’t work. My favorite line in the paper is the one highlighted, "Growth cannot increase everyone's relative income." Pareto optimality is incongruent with our biology, and Prof Daly recognizes this – his arbitrary 100:1 max-min may make sense on paper but how do we convince the ones currently in power to give up their relative advantages?

Here are my brief comments on the rest of paper:

-An ‘economics’ that puts high values on resources at the beginning would be an improvement, yet cap-auction-trade suggests that a pricetag can be put on everything – certainly many things should not be ‘sold.

-Limiting throughput, and thereby achieving low birth and death rates, strikes me as difficult to reconcile with human nature unless done in a sneaky way.

-Redistribution seems to be a recurring theme in ecological economics and some environmental circles. “Fairness”, as our society markets it might be our biggest stumbling block in the end. It’s odd that we harp about how much inequity there is yet as individuals constantly strive for it. “Human fairness" is a red herring which may sabotage many very logical possibilities. Indeed, I wonder whether the drive to achieve fairness on a finite planet with unlimited reproduction isn't the least fair thing possible. Discussion of the "proper range of inequity", be it 4 or 100, is to some extent -- just human wankery. The universe isn't fair, and never will be. Even among wretches with no physical possessions, one will have better vision, another a longer dick, another a more pleasing balance of brain chemicals, etc. Abandoning the pursuit of perceived fairness could be the best thing which could be done... and probably one of the least likely.

-Regarding competing for knowledge –this is a great idea, provided people don’t use the knowledge to compete for throughput. I get the sense that many if not most of this websites readership are trying to obtain knowledge here that will increase their own relative fitness, either through investments, or better preparation for collapse by knowing timing and magnitude.

-I liked his mention of going for fewer but more durable goods – you are investing low cost energy and making it still 'exist' in the future in embodied goods. This means less profits in the discounted cash flow models though, so convincing economists of this is probably hardly worth doing...

-Taxing at the mine or wellhead is a good idea. Good luck with that. A lot of this gets close to utopianism... laddering into saner taxes also tends to strike me that way...

While Daly may have been ahead of his time with ideas, time has past the feasibility of most of them by - there are now far fewer options left and most are heretical from standpoint of established institutions. (certainly not his fault - he's been saying these things for a long time and no one has listened) But he does make clear that money itself has become "unsustainable" because it can cross borders and cause depletion of resources just like people (or locusts) can. The only answer is to stop the flow of money and people -- and re-allocate assets.

Cornelius, you write:

That's a very perceptive comment. My only fear is that many readers may have missed it because of the average blogger's limited attention span -- even at the TOD echelon. I think people tend to skip over any comment that takes up more than one screen, and that's why I'm quoting it above. But I wouldn't be too cynical about our motives --- besides, there's nothing wrong about trying to improve one's chances of survival provided one isn't banking on the failure of others as part of one's strategy (like selling short, for example).

Now I'll get around to reading the rest of your comment ...

Historically there are almost zero cases of achieving what you ask. Therefore you can draw whatever conclusions you think are probable based upon the answer to your question being "they won't give up those advantages willingly."

Back where I come from, there are men who do nothing all day but good deeds. They are called phila-, er, er, philanth-er, yes, er, good-deed doers, and their hearts are no bigger than yours. But they have one thing you haven't got - a testimonial. --The Wizard

We mock Walmart or other examples of giving out employee recognition in place of an adequate living but Daly points to the military where pay disparity is not so large as 100:1. Why is this? The top ranks are payed in respect rather than money. When you are at the top, you have a chest full of testimonials. Military effectiveness depends crucially on force cohesion and too large a pay disparity gives the impression that the officers are not looking out for the troops which reduces morale and cohesion.

We have on-going examples of limiting pay disparity. Some automakers do it deliberately to get a more loyal workforce which provides a competitive advantage. The thrill of beating the competition seems to be pay enough in those cases.

Money is actually a surogate for respect and recognition after a certain point and the present too high compensation is actually a sign of distrust and disrespect, an attempt to buy loyalty to a company from those who lack the character to be loyal otherwise.

Chris

The two paragraphs below were written by Garrett Hardin for a speech he delivered on June 25 1968. The speech was the basis for the article "Tragedy of the Commons" published in Science on December 13, 1968. The elegant and extremely radical notion embodied in the article and his other writings as well explain why he was marginalized as ferociously and maliciously as was.

His writings posed then and pose today a threat to the existence of every economic, political, environmental and any other power center you can name.

The truth of what he writes is undiminished by time, only the urgency for accepting what he is saying has changed.

Hardin writes:

At the end of a thoughtful article on the future of nuclear war, Wiesner and York (1) concluded that: "Both sides in the arms race are ... confronted by the dilemma of steadily increasing military power and steadily decreasing national security. It is our considered professional judgment that this dilemma has no technical solution. If the great powers continue to look for solutions in the area of science and technology only, the result will be to worsen the situation."

I would like to focus your attention not on the subject of the article (national security in a nuclear world) but on the kind of conclusion they reached, namely that there is no technical solution to the problem. An implicit and almost universal assumption of discussions published in professional and semipopular scientific journals is that the problem under discussion has a technical solution. A technical solution may be defined as one that requires a change only in the techniques of the natural sciences, demanding little or nothing in the way of change in human values or ideas of morality." (emphasis added)

the full article can be found at http://www.garretthardinsociety.org/index.html

I haven't read the linked article yet but the part that you pulled out reminds me of the distinction between change and transformation and how change so often is used, mostly ineffectively.

Here is how I shall define the two terms:

Change is past-based because it takes an existing system and modifies it. Thus it often brings many of the consequences of the old system with it.

Transformation is future-based because it is created from what the future contains — which is nothing. With transformation, something wholly new is created.

It is common to hear people calling for change. A politician often finds the message of change a useful one to win an election. But even when the politician is successfully elected, embarks on change and change occurs, why does the system always become something that looks remarkably like what was there before?

I assert that's because the politician used the wrong tool for the job. When transformation was called for, they used change instead.

To be fair, it's not entirely the politician's fault. Ask them what transformation is and they are unlikely to give you a meaningful response because it is not a concept the West is familiar with. It certainly isn't embedded in our culture like it is in some others. When it does come up, most times it will sound like change done to the extreme. Even asking experts in transformation will bring forth several different concepts. In the paper here, the author says:

That is all well and good, but what does he mean by a "fundamental internal transformation of all mental activity?" To what? From what? Isn't that scary?

This is an involved topic but starts to point at, I believe, what will be required to achieve what Hardin wrote. The difficulty is that in my view we largely have run out of time to disseminate the concept of transformation before collapse occurs.

Of course, inside of transformation, there is nothing wrong with collapse. It is just the universe doing its universe thing.

If you see that as callous because of the untold numbers of people who will likely suffer and die, you will also see the difficulty the teachers of transformation have. But they will not see it as difficult because that is not an empowering context in which to operate. It is just as it is and is not any other way. It is neither good nor bad. It just is.

-Andre'

(smile)

This is wonderful, André. Transformation is precisely what will be needed as the world goes through the change. I'm convinced that human transformation is the only reasonable (and perhaps the only possible) way of successfully addressing the converging crisis.

It's interesting to watch the growing awareness and the rising tide of consciousness out there. I mean, Oprah Winfrey working with Eckhart Tolle?? It's simply remarkable.

Fear of the idea of collapse is just the ego's fear of annihilation. The more violent the objections to even thinking about the possibility become, the more you can be sure the egos are speaking.

We need to live Now. Destiny will take care of itself.

Hi, GliderGuilder.

Yes, I often fall into the trap of becoming worried about my own annihilation when I think of peak oil. As far as I can tell, it's something evolution selected for otherwise my ancestors wouldn't have survived and I wouldn't be here. That doesn't change the fact that it's a pure physiological/mental response that makes sense for the perpetuation of the species but can make my life uncomfortable right now.

When I can quiet the chatter in my head, I can get to "I am now, then I won't be" — and then interrupt the mechanism that makes that mean anything other than "I am now, then I won't be." I don't have a religious practice so I think that's all there is. (Many religious practices, in my view, are responses to people's discomfort with confronting the eventuality of "not being.")

It is true that destiny will take care of itself. It always seems to. Despite that, I do see something for myself in taking action on the issues facing us. Occasionally I bump into people who make transformation mean that there is no reason to "work on our problems." (This is not so many, actually.) This is the flip side of people who devote their life to solving problems, but suffer immensely because life has become heavy and significant for them. Though a representative of each camp would look at the other as though the other were crazy, both approaches are entirely valid ways of living life.

But what is possible if one were to combine the two approaches? What if one were to play the biggest games available, but play them with ease and fun?

Couldn't we then enjoy life as we improve the conditions of humanity the planet? Even in the face of the calamity before us?

Isn't that what Viktor Frankl saw possible? The German title to his book seems to convey more than the English one: "...saying yes to life regardless: A Psychologist Experiences the Concentration Camp" (...trotzdem ja zum Leben sagen (Ein Psychologe erlebt das Konzentrationslager).

That seems to be a worthy practice to take on and one that I do for myself: to live life regardless — while playing the big games that inspire me.

-André

P.S. I've gotten value from Eckhart Tolle's books. I'm up to chapter six of his latest.

Excuse me while I push past all these angels dancing on the head of a pin.

Too bad you didn't take the 15 minutes it would have taken someone obviously as erudite and well read as yourself to read the 13 pages written in 1968.

Had you, you would have recognized an eloquent—and ground breaking— argument making the case for transformation (a thorough or dramatic , change in form or appearance) that you feel a need to make distinct from change (make or become different; make or become a different substance entirely; transform) though there is no difference in meaning in common english usage.

Describing angels at play on pin heads I guess transforms language into what ever we want it to mean.

While it is nice to have the comfort of a spiritual belief to condone all our human behaviors the point Hardin was making in this article and through out his works is that absence a fundamental internal change within us all you simply can't get there from here.

We all suffer Dukkha.

In the words of a long dead and anonymous Zen master—"We are the ignorance that blocks out reality."

Yes and no. Of course I want to improve my own prospects. But the way in which I'd like to improve them need not be at the expense of another. As the article says, knowledge is a thing which does not become less as it's shared out. So by improving my knowledge, I'm improving my fitness, but not necessarily my relative fitness.

I'm also very interested in everyone being able to improve their fitness. Some people have fantasies of sitting on their cases of ammo and spam and gunning down hordes of suburban cannibals made desperate by overnight collapse. I don't. I have fantasies of a better future for the world, one where everyone has water, locally-grown food, shelter and clothing, productive employment, access to education, where the rich-poor gap is not too great, and so on.

I think we can achieve my little fantasy, some places are already moving towards it. But it requires knowledge.

I have to agree in practice and disagree... in practice. It is only in modern times that the idea of sharing has been considered heretical. We put labels on sharing by calling it communism, collectivism and socialism. Yet, this is the only way societies exist in a steady-state economy. What is really amazing is that people assume such societies exist only in the fevered imaginations of wild-eyed liberals, socialists and communisits (etc.). This is far from the truth. What is truthful, however, is that we have never managed to do this on a large scale. (That does not mean area, but population/complexity.)

On smaller scales, small populations do exist this way. I posted an example in a recent DrumBeat. Diamond also offers examples. Others exist, of course, if you're of a mind to google. Many North American Indians lived this way, at least within the breadth of their own tribes. On an even smaller scale, and a little less apt an anology, Americans lived this way to an extent as they went West. Barn raisings and other such activities were seemingly altruistic actions that actually were a matter of self-preservation as small communities counted on neighbors more than modern Americans do.

Human greed for power and money are the root of all evil. This idea that one person not only can have more than others, but that it is our inalienable right to have more than others pervades the current paradigm. And in the end, that right is backed by might, whether it be physical or economic. (This despite most people considering themselves to be religious and being told to live in service to one's brother; to give half your cover to the naked one you meet in the road. Ah, the irony...) A steady-state economy is nothing more than learning to share at a societal level without demonizing that by naming it with some pejorative term. Were politicians to successfully drop the huge weight of pejorative labels we have allowed ourselves to be labeled with, the change might be enormous. Why should feeding the poor be "socialism" when capitalism creates an eternal underclass? Why is capitalism not called parasitism, since that is exactly what it is? It is the shark/lamprey relationship in reverse. Capitalism cannot exist without cheap labor. Cheap labor = an eternal underclass. In the end, the ideas espoused above are about as close as we may get to transitioning the current civilization's basic structure to something resembling equality because we will certainly never overcome human greed - or any other of our vices - so long as we live in groups large enough to allow us to demonize/objectify our neighbors. Dunbar's number and all that.

The great weakness in the essay is this: it requries a slow transition on a global level from a parasitic to a cooperative society. When has this ever happened before? In truth, we have not lived in such a way since we left the Stone Age. We live that way now only in those societies that never left the Stone Age. We abandoned cooperative living yea these many thousands of years ago. How realistic is it that we can successfully transition back while keeping the best of what we have created since then?

To do so would require us to, indeed, relocalize. To learn to share again, and like it. To live with others closely. To abandon the self to the whole in the greater degree while reserving some small portion for ourselves where it does not conflict with the survival of the whole. And to like it. To not only live in balance with nature, but to seek to do so. And like it. Etc.

Most of all, it requires us to repudiate forever the idea of leadership that does not arise directly from the people, and is directly answerable to same. Not over 2 to 6 years, but immedaitely. The end of "leaders" in favor of nominal chiefs/big men as decribed in aboriginal societies is a must. For greed is what it is. The love of power does, indeed, corrupt. And it is the lack of bonds between us that allows the community to accept immoral and unethical acts upon our neighbors - and to commit them. Whether it be rape, usury, price gouging, theft or exploitation of workers, this is not possible when we are a close-knit community if the community stands on the principle of fairness and good for all. It is not possible if we know and have some degree of bond with our neighbors. This does not mean immorality or unethcial behavior will not exist, only that a cohesive community can check such behaviors either by punishment or by providing the external stimulus to control our impulses. The combination of human nature and a lack of community creates a vacuum into which the powerful sweep and build their power bases.

One final thought: For all this to work, we must also include a simplification of the legal process. It must be pared down to a short list of principles by which a jury judges right and wrong, guilt and fault. Put the power back in the hands of the people. The extreme complexity of the legal system favors those in power (of whatever form.) Juries must be in position to protect the community from laws being twisted. The greater the number of laws, the greater the number of loopholes. The current president, for example, could not possibly avoid impeachment were the legal system and the congress of the mind that the Constitution, as *the* law of the land, must be enforced. To wit: in referring to the Chief Executive, "...he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed..." By failing to do this, the president is in violation of the law of the land. One need know no more than this to see that impeachment is not only justified, it is necessary to restore the balance of power to the people. This priciple should apply at every level. When a company dumps toxic waste, when a teller embezzles money, when Exxon knowingly lies that Climate Change is bunk, when Enron manipulates power supplies... etc.

For example: did Enron manipluate (manipulate = lie)? Yes. Guilty. Anyone who knew this and did not act to stop it is also guilty. Anyone. Did BuCheney mislead about Saddam/al Queda (mislead = lie)? Yes. Guilty.

Let the jury decide their fates.

So.... can we make this transition peacefully? No. I do not think so. Walk outside and look at the nighbors around you. How many of them would you sacrifice for? How many of them would sacrifice for you? How many of them can you trust? How many of them **do** you trust?

How many of them are not a product of this age? How many of us are? How many of us, here, could make this transition?

How many are?

If it is possible, relocalizing and the end of strong governments at every level are musts. The end of usury and the fractional banking system is a must. A willingness to live within the bounds of the natural system is a must. (This list is not exhaustive.)

Cheers

The recommendation on the World Bank does not go far enough. Spectacles, hearing aids and flatulance drugs don't help when the bank is in thrall to the fossil fuel interests. Funding 4 GW of coal generation in India shows that the problems run much deeper. Perhaps a downgrade would cause the bank to do less damage, but it needs more than that I think.

Chris

SSE provides the essential impetus to creating a system the rewards sustaining behavior, though halting population growth is still not fully addressed from the above description. I expect most economists to simply outright dismiss such a policy, though many are shocked that Malthus' predictions may indeed be coming true. Perhaps that's enough to shake them from their obeisance to infinite growth economics.

It's not clear how SSE would treat certain renewable resources that still need protection, such as rainforests (clearcutting/burning) and streams (mountaintop coal extraction).

Any libertarians have comments on SSE?

What about the Maximum Power Principle (Howard Odum's proposed 4th Law of Thermodynamics) ? According to the MPP living systems (including cells, fruit flies, alligators, dogs, humans, etc., etc.) tend to organize in a way that uses the maximum available energy as fast as possible. NOT as efficiently as possible. AS FAST AS POSSIBLE. We are living systems and we are simply born to behave in a "growth" way. Perhaps being aware of the problem (like an addict who stays away from a bottle of whiskey) may help for a while, but can this basic biology be changed??? We are biological beings, whether we like it or not. If available energy is curtailed, as peak oil says, then people may die when they're not in their 80s, but instead in their 60s and start families when they are younger. But sticking to a plan to stabilize population and dictate no growth seems like it would not be popular (look at China). People want growth (even if it is denied they'll try to get it or die trying to get it) and they'll still fight wars to get resources to support their own group's (nation's, tribe's, etc,) growth even if it's just the tribe across the river and they're just fighting with sticks and rocks. Anthropologists even characterize war as something that relieves population pressure.

It doesn't matter if you think you're above the MPP, or that you don't like it and don't want to play by its rules. Perhaps certain segments of society (Henry David Thoreau, some ascetics, religious figures, etc.) have opted out of the MPP but most people (99.99%) wouldn't dream of acting contrary to the MPP.

Huh, I hadn't heard of it. Its quite inappropriate to include in the laws of thermodynamics because its not predictive the way the other laws are, and it doesn't have the same rules of the dismal game analogy.

Even though I don't think much of it, its the opposite of what you describe:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maximum_power_principle

It basically states that systems tend to extract the maximum work out of energy transformation.

Im writing a post on the linkages between MPP, Hubbert Linearization and our overall predisposition to deplete resources to maximize current utility. There are some problems with that Wiki entry (though not many) -best to read some of Odums/Halls/Schneider original work.

And I agree with first poster that this is one of fundamental laws of how ecosystems and organism were organized (and continue to be so). We abhor a gradient, and free energy stored in fossil fuels is about one of the steepest gradients imaginable. We couldn't use it all at once, neither will we use it efficiently, but at intermediate rate and intermediate efficiency (with huge waste). Its amazing that other organisms follow this rule, which makes it more robust that humans carry the genetic wiring, at least for the mechanism. More soon.

I got this far (my emphasis)...

...and sprayed coffee all over my keyboard. Is this guy really a professional economist?

What made you spray the coffee is the typical run-of-the-mill economist concept. They consider "steady state" to be an economy maintaining a fairly constant ratio between labor, capital, etc... even as it grows. And yes, unlimited wants - that's why economics is the (pseudo)science of scarcity, because one can never satisfy all the human wants.

From last year, a discussion with Brian Czech (mp3) addresses exactly this point toward the end.

Scale, distribution and allocation. The market only handles allocation. Scale is killing us and distribution is why most of us have so little power to change matters in a positive dimension. Someone upthread suggested it be done sneakily; I'd advocate doing it as broadly and openly as possible. "What will be fair and who will decide?"

cfm in Gray, ME

We WILL end up with a steady state (or sustainable) economy. Once we've depleted all of the non-renewable resources, we will have no choice but to live within the carrying capacity provided by renewable resources. This is true IF we manage to avoid outright extinction, that is.

There are policies that could be followed to make the transition easier, less painful, and less deadly for more people. Prof. Daly has prescribed many of them, though we could probably add to his list, especially with regard to energy. Unfortunately, I am not optimistic when it comes to governments making wise and timely policy decisions.

Agree, WNC. In the "land of droughts and flooding rain" (Australia), after thousands of discussion hours and millions of tax-dollars, the government still can't decide whether to ban plastic shopping bags or not... So if PO gets on par with Global Warming as a so-called "urgent" issue, what faith can we have in politicions doing the right thing?

But what the heck, it's probably time for a decent global shake-down and I'd rather watch a decent sunset than the latest block-buster on a Hi Def plasma anyway.

Sure, but 10^26 watts of solar power is a steady state economy just a tad bit larger than our current one. The notion that we're close to the end of growth is obviously silly.

Yes, but where is the plan to get us from here to there --- and the capital funding that would be required -- and the wise and effective leadership to make it all happen? It is getting VERY late in the game, way past time for mere talk, and urgently in need of action.

Seriously? One might wonder how we industrialized to begin with when there was far less capital, everything cost more in every possible sense and the leaders of the day were all looking for any possible way to butcher each other at any possible excuse. The way forward today looks far more credible. Of course there will be problems on the way but the end of growth just isn't in the cards for centuries.

we industrialized at a time when there were huge surpluses of raw materials, and much smaller populations

we've used up a mind-boggling amount of those resources (and there aren't more being created i.e. abiotic oil) - and we have ever-increasing populations

so explain where the growth will come from as we have peak in crude oil production, are close to nat gas peak, not far from a coal peak - experiencing peaks in many other materials and foods - I just don't see it

and further more I am hoping not to get it - since more industrial growth just means a steeper cliff, more AGW and the potential for a bigger die-off

Where will we ever get more whale oil?

Our limits aren't what you think they are.

I'd like to be polite - but the whole "whale oil" argument is really really inane - in fact, we DID over-fish the whales, and if crude oil hadn't been a cheap and convenient replacement, it would have been back to tallow and wax candles (btw, whale oil for the 19th century was NOT the equivalent to crude now - coal was - whale oil was a specialty item for lamps and some industrial lubrication - hardly the energy foundation for the whole civilization like crude is for us) now our populations have grown even larger on a steady diet of crude oil, natural gas and coal - which are all running out quickly - and you, without any attempt to explain expect me to simply believe that something will just turn up?

unless whale oil is the replacement for crude - bringing it up is as stupid as the equally dumb "the stone age didn't end because we ran out of stones" argument.

point out a replacement for crude oil and natural gas that is waiting in the wings

"Our limits aren't what you think they are" - oh really? surprise me with some sort of explanation of this statement - where is the replacement for liquid fuels?

You really think there aren't replacements? 120 trillion tons of fissionables in the ground and 10^16 watts of solar energy from the sky with hydrogen from the seas and carbon from the rocks and the air you can make as much liquid fuel as you want.

Likely true, but at what cost, over what time frame, at what social equity level, and what social freedom level?

I agree with Nate and the others Dezakin. Clearly you have swallowed the neoclassical economics line whole, despite its inherent implausibility. The problem with oil is scale - no combination of all of the alternatives, either singly or together will or can replace the energy contribution of oil anytime soon, either in time or in volume. That is why this site exists.

If you want to enter into a circular discussion about unlimited growth I suggest you go to the high priests of neoclassical economics - The Mises Institute.

In the mean time, just to demonstrate that you are not alone I will leave you with a favourite quote that Jay Hanson also likes:

BTW, Herman Daly is not only an economics professor, he is highly celebrated. His work comprised a significant amount of my reading for my Masters degree (Sustainability Sciences). I have the utmost respect for him and his economics.

You're fighting a strawman in bringing whos economic ideology is best game. Have at it if you like.

Its been illustrated that all the alternatives can replace oil, and nuclear, solar, or wind can each do it singly. The issue is simply cost. I'm simply saying growth wont end, not that there wont be a cost, because the liquid fuel infrastructure replacement cost would run into tens of trillions globally easily. Costs of running all of civilization on nuclear would be some 10000 1 GW plants today, for some 30 trillion, and for wind its similar. Add in grid costs, infrastructure replacement for synfuel plants, rail lines, and the like, and its obviously quite pricy, but well within the realm of affordibility for the globes 60 trillion dollar economy.

I suspect that the transition will be relatively painless, but it could also be a multi-decade long inflationary low growth/recession period as all the capital and labor are sucked out of productivity enhancement and back into infrastructure. But it isn't the end of growth or even close, and this apocalyptic alarmist nonsense about the population crashing and being at the apex of human civilization has got to stop.

The problem Dezakin is time. As Nate wrote above, I also have no doubt that theoretically these energy sources could replace oil, the problem is time, investment, infrastructure and political will. Right now, apart from this site and a few others like it, there is zero understanding of the energy problem we face (with the possible exception of a small and unpleasant cabal surrounding VP Cheney).

Certainly the UK and Australian governments continue to demonstrate an alarming degree of ignorance and indifference to the importance of oil.

I am not so sure you are right though in practical terms. Nuclear? There are problems with Uranium supply - we are already exploiting lower quality reserves. Wind? Huge oil derived infrastructure requirements. Solar? Ditto for wind. Bio-fuels? Finite land (actually arable land is declining). You may have noticed there have been one or two problems with food supply in the last few weeks?

So while I agree in theory, I disagree absolutely in practical terms. "No combination of alternatives....etc"

I don't think it's time. I think it's thermodynamics.

Greer wrote about this last fall, in an article called Solving Fermi's Paradox. It's about why technological progress is not unlimited.

If you think its about thermodynamics, you fail. One side of the sky is 6000 K and the other is 4K.

Agreed Leanan, but in the context of this particular discussion with Dezakin simplicity is important, as is amply demonstrated by his response to your post. He clearly hasn't grasped even the basics of the issues surrounding PO.

Try again. Thermodynamics aren't a limit. Go ahead and try to show they are, you might find you dont actually know anything about thermodynamics.

Actually Dezakin I do not have to prove anything to you, this site is led by an illustrious and intelligent group of people who have done much to educate a large group of readers. It goes without saying that your views are not well supported on this site.

The fact that I come here to learn and to interact with other like minded people is my affair. I expect to do so with robust but polite discussion. I am not only a chartered accountant, but have a Masters degree in Sustainability Sciences - the very stuff of this site. In other words I have undertaken formal academic training in the subject and thus can justifiably claim at least a basic grasp of many of the topics discussed here. Many other people have much more than a basic grasp - they can properly be classed as world class leaders in their subjects.

The one thing that binds us all here is a significant level of concern about the ignorance and indifference our political leadership shows towards these subjects. One overt objective of this site is to raise the level of knowledge and understanding that the general public has about these issues - and that this site achieves admirably.

Neoclassical economic teaching has informed government decisions over the course of the last several years and still is doing so. The disciplines worship of the market is now being questioned and rightly so. Not that I don't believe that the free market is not the best vehicle for allocating all sorts of things - of course it is. But it is also true that there are also significant market failures. Oil is one. Long lead times mean that the market cannot correctly signal investment decisions or even a price that reflects oils scarcity value. Climate change is another - property rights cannot be ascribed to air so this is a true Tragedy of the Commons. Thermodynamics is not catered for anywhere in neoclassical economic thinking and thus much of the discipline is irrelevant in todays world. Economists without a basic understanding of resources are simply not wired to be relevant.

Note that the comment above about climate change is not intended to invite a long thread fighting over climate change. It is enough that a significant group of people want less CO2 pumped into their share of the air - and they have no way of stopping it. That is market failure.

So much for the explanation of why we are here. I would advise you to be more respectful on this site. Sure - we like robust discussion, but remember that most people do not have the time or inclination to write long fully justified comments here. A certain level of knowledge and understanding is presumed.

BTW I am an atheist - I do not subscribe to "end times" or any other religious topic. I am concerned about human overshoot; and that is another well established principle, but this time the subject is ecology.

Nice nonsequiter; Truth isn't a democracy of wild opinions.

Your long winded righteous indignation has absolutely nothing to do with the fact that thermodynamics aren't a limit to civilization, and if you knew anything about thermodynamics you'd realize it. You can argue societal limits of human organization, ecological limits of environmental footprint, anger of the gods or some other untestable proposal that will prevent future growth as well as blovaiting complaints about neoclassical economics or whatever is your favorite devil, but it has absolutely nothing to do with thermodynamics. Sure, you don't have to proove anything, but don't think it actually helps your credibility.

Actually Dezakin I think you will find that "thermodynamics" represents very real limits to growth. All species require usable energy and humans in the modern context need huge amounts of usable energy. Less usable energy is going to be available to humans in the near future and that is going to cause us problems, most likely through the impact on our economies. You may not believe that, but many on this site do. There is also a very significant body of evidence that supports that contention. Usable in this context means the right amount of energy in the right place at the right time and in the the right form. One can die of starvation in the hot sun.

Not exactly sure what you mean, but if you mean population overshoot (of any population of any species in a specified environment) then I think you will find the principles are well established and have been understood for a very long time. They are hardly untestable - in fact the principle is so obvious it should not need testing. Yeast in bottle of wine is a good metaphor for the human population on earth. (Note I have specified which population, species and environment.)

In fact there is/was a long time contributor on this site whose tag line was Are humans smarter than yeast? It is a very good question.

Look, you can keep arguing it if you want, but you arent going to find any support that this is an application of thermodynamics. The usable energy is defined by what you can get out of a heat engine, and has a definite number. You're trying to describe capital and labor shortages that prevent construction of said heat engines, but this isn't an application of thermodynamics! You dont know what you're talking about here.

Sure, and the answer is consistantly yes. I suppose the question 'does human civilization follow the same growth pattern as yeast' just isn't as snappy; Its a nice analogy, with the caveat that civilization isn't static and the size of the petri dish is the size of the universe.

I grow weary of this thread, but I am not sure where heat engines come into this discussion. The laws of thermodynamics have much wider application, specifically as they relate to humans in this context for food, transport fuels and much else besides.

In fact the reference to heat engines is illuminating. Do you think the laws of thermodynamics are specifically and only about heat engines?

No it doesn't. Thermodynamics applies to how heat moves in systems, from hot to cold; The study of thermodynamics grew out of analysis of heat engines and carnot efficiencies is an application of the second law. The sun will be hot for billions of years, and the sky will be colder than other parts of the universe for many trillions. The limits of thermodynamics only say that we can't extract work from the sun at greater than the average temperature of the sun compared to the average temperature of the sky. Applying thermodynamics as a limiting factor is simply ignorant of what thermodynamics describe.

As I said: I grow weary with this.

Wikipedia:

I am not sure how the sky etc is relevant, however energy available to do work for us humans must be in certain forms, or be available and capable of conversion into such forms to be useful (taking entropy and economic costs into account). That depends to a great extent on the systems surrounding us; including human made systems. That in turn implies links with our economy, investment and legacy infrastructure. For instance, I agree that fuel cells can drive cars, they are just not going to drive 800m of them in a meaningful time scale for a whole bunch of reasons.

Wow, you cited an entry without understanding it at all.

The night sky is relevant because its the heat sink that slowly increases in temperature (were the universe not expanding) as heat flows from the stars to the sky. As long as you have something hotter than the the sky you can extract work from it. This is the only time we really consider entropy as a thermodynamic limit. The amount of work you can extract depends on the temperature difference between whatever's warmer than the heat sink (the sun, a fission reactor core, a gravitationally collapsing accresion disk, whatever)

We aren't running into thermodynamic limits when we receive sunlight that's 6000k with an environmental heat rejection limit of 300k and a total solar energy budget of 10^16 watts. The carnot efficiency we can achieve in ideal systems here means we can only extract, hrm, about 10^16 watts. You aren't making arguments based on thermodynamics. If you were you would have a nice equation with our total avaliable energy and a clear unambiguous answer that we couldn't argue about. We can definitavely say we can't get 2.5 gigawatts from a 3 gigawatt thermal light water reactor run on the steam cycle for thermodynamic reasons, and this is the problem domain of thermodynamics. Thermodynamics sets the limit of how much nuclear power we can have on earth, because if you have significantly more than 10^16 watts, the planet gets too hot for human habitation. Thermodynamics tells us that we cant beam in more than 10^16 watts of electric power from solar power satellites for similar reasons. Thermodynamics tells us the limits of how much biofuel can be synthesized by a plant, how much hydrogen can be yielded from a thermochemical process, the energy losses from conversion, and the maximum amount of information that can be processed in a given space by a given mass of matter. Attempting to use thermodynamics to argue that we're facing near term limits to growth for thermodynamic reasons is simply ignorant of what thermodynamics describe, because these limits are clearly defined and orders of magnitude beyond what we'll be facing anytime soon.

Sure, and it has nothing to do with thermodynamic limits. It has to do with capital flows, financing, cometitive technologies and other things that have nothing to do with thermodynamic limits. Thermodynamics says its entirely possible for 800 million 100kw fuel cars to be constructed and driven continuously fueled by 25% efficient solar thermochemical hydrogen production because its well within the solar energy budget.

As I said I grow weary. Have your universes and your stars. You clearly have some knowledge, but you seem incapable of connecting the dots. Thermodynamics concerns systems however "small" in comparison with the night sky.

And yes, everything is relevant, including capital, economics, investment, ecology etc etc AND thermodynamics.

Give it up! This isn't your field, and you're out of your depth. You're now errecting strawmen and nonsequiters that have nothing to do with my original statement. Of course thermodynamics concerns small systems! Its why you get engine efficiencies of 15% or so in your car and don't get 200 miles to the gallon, why you have to spend energy irreversibly to refine materials that have gotten mixed, why steel costs more than concrete. Thermodynamic limits aren't what is preventing growth. I would argue that economics, capital, investment, and ecology aren't preventing growth either, but we can show that thermodynamics isn't preventing growth because if it were, everything on earth would allready be dead.

I hate to come along and be supportive of anything Dezakin says, but... Dez mate, seriously, this is a fart in a wind tunnel. Don't waste your time on this guy.

I am not sure it is yours either.

All systems suffer from a variety of constraining factors and the laws of thermodynamics definitely play their part in constraining what is possible. You need to connect the dots - everything is connected. There is no point in considering any of the issue discussed on this site in isolation. They may be discussed in separate threads, but they are discussed within a very broad context.

Unless some other source of energy is found and commercialized, or some new technology that somehow delivers energy is invented and commercialized, the lack of growth in oil production will continue to cause distress. Turning full circle - No combination of any of the alternatives can replace oil within a meaningful timescale. That is because the properties of oil are unique. It is the zenith of mans energy equation, at least for the time being. Unless any replacement is seamless, there exists a risk of economic dislocation, quite possibly depression, maybe even outright chaos.

If you do not accept or understand that statement, you have not thought all these issues through and your understanding is limited. You should go away, give up looking at the sky, and get down to some serious reading.

Does thermodynamics tell us how much of that solar budget is not used by the earth's biosphere now, and so is available for our use and what resources are needed to harness that?

I think you're referring to theoretical limits, not practical limits. It is the latter which is of concern to us, not the former.

I'm not disagreeing; Thermodynamics describes no limit that makes it impossible for human civilization to consume galaxies. Suggesting that thermodynamic limits make growth of civilization beyond where we are impossible is simply ignorant of what thermodynamics actually describe.