The Next Five Years: Peak Lite and the Current Oil Picture

Posted by Robert Rapier on March 26, 2009 - 9:28am

A few years ago, after spending a lot of time thinking about peak oil, and then watching the price of oil break out of its historical trading range and head higher, the idea of Peak Lite came to me. Over time the price of oil had bounced between $10 and $30 a barrel, but about 5 years ago it broke from that pattern and started the steady climb that culminated in $147/bbl last summer. I had been having various debates about whether we were or weren't at the global peak in oil production (I was taking the 'not yet but soon' position), but it started to become clear to me that we didn't require a global peak before we started to feel the impact of peak oil.

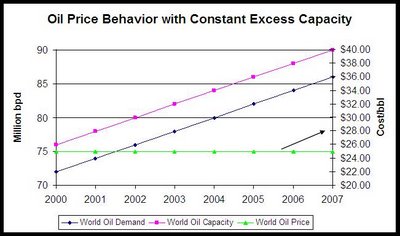

I proposed the following to explain what I thought was happening. (Don't get too fixated on the dates or prices as they are just there to illustrate the concept). Figure 1 shows the sort of price behavior if spare oil production capacity is constant. Of course spare production fluctuates up and down, as does price, but my thesis is that constant excess capacity should keep the price relatively stable - as long as the excess is large enough that several different producers have the ability to step up and fill shortfalls. This concept is illustrated by Figure 1, with a constant four million barrels per day (bpd) of excess capacity and an oil price of $25/bbl.

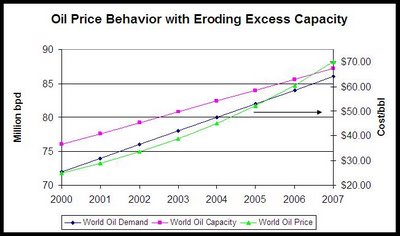

Figure 2 illustrates the case in which demand growth is outstripping supply growth, leading to diminishing spare capacity. This is the mode that we have been in for the past few years. Spare capacity was eroded by several million barrels during the first half of this decade, and as a result the price of oil climbed higher, and became increasingly volatile. This was caused by a combination of stronger demand worldwide, and an oil industry that had not anticipated such strong demand growth. As a result, the global oil industry didn't invest aggressively enough to meet demand, and while capacity did grow, it didn't grow quickly enough to keep prices stable.

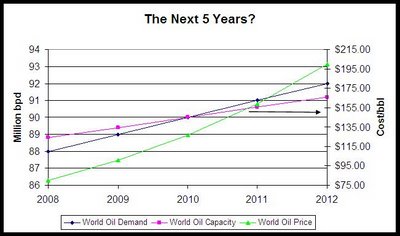

Figure 3 illustrates a future in which world demand has collided with world supply, and then demand growth continues to stay ahead of supply growth. In the world of peak oil, this happens because supply is falling. In the peak lite world, it can occur even if supply is increasing. In the figure, I show an example of supply and demand colliding in 2010, then demand exceeding supply in future years. Of course demand as defined in Economics 101 won't actually exceed supply, demand will just be destroyed by rising prices (as shown on the right axis) to keep it in equilibrium with supply. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate what Peak Lite is all about; that you don't have to have falling supplies to start experiencing the effects of peak oil.

I created the original figures in mid-2007, and as we know by mid-2008 oil prices had risen much higher than the $95/bbl I illustrated on the figure. But circumstances have changed. As a result of climbing oil prices, new projects have begun to come online. Strong price signals from the previous five years had resulted in major investments into new oil production (but it takes a few years to bring new projects online); about 5 million bpd of new capacity was expected to come online in 2008 alone.

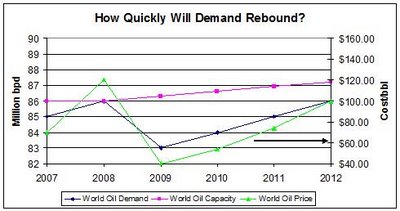

At the same time, oil prices climbed much too quickly for the economy to even begin to adjust, and this contributed to the overall economic collapse. The combination of high prices and the economic troubles have taken a bite out of demand (at least temporarily). So we essentially find ourselves back in the position of having perhaps three or four million barrels of excess capacity around the world, and oil prices back in the $40's. Thus I think Figure 4 explains where we are now - and where I think we are headed.

In Figure 4, the year 2007 shows a world in which oil is at $80 and the demand has nearly caught up with supply. 2008 shows an example of no spare capacity, and the oil price sharply higher. Then 2009 shows the situation with reduced demand, some incremental capacity increase over 2008 (new projects scheduled to come online in 2009 will generally be too far along to cancel), and the corresponding price collapse arising from the largest spare capacity situation in several years.

So, where do we go from here? I think it depends on how quickly demand bounces back.

The Next Five Years

What might the next five years look like? Do we revert back to Figure 1, in which we see steady prices for years (except this time in the $40 region)? Or do we return to the eroding capacity case of Figures 2 and 3? I have reason to believe the latter is the case.

One reason for this is that the oil industry needs higher prices to warrant new projects. Sig Cornelius, the Chief Financial Officer of ConocoPhillips, recently stated that oil needs to average $52/bbl in order for the company to break even. The cost of finding and developing oil has gone up, and recently Eni CEO Paolo Scaroni said that oil prices would need to be $60 to keep up the needed investments. As a result of low oil prices, drilling rigs are being underutilized and projects are being canceled:

E&P Capital Expenditure Cutbacks

The International Energy Agency estimates that about $100 billion of worldwide oil production capacity expansion projects have been cancelled or postponed over the past half year. According to Barclays Capital, oil companies have cut worldwide exploration and production spending by 18 percent so far this year. Deutsche Bank estimates that U.S. energy exploration-and-production spending will drop $22.5 billion this year, a 40-percent, year-on-year decline.

Saudi Arabia has cancelled the development of several fields such as the Manifa and Dammam oil field, which would have added about 1 million barrels per day (MMBpd) of capacity. Refinery projects have also been delayed or cancelled while Saudi Aramco reviews cost estimates in the light of the significant weakening of oil prices. Saudi Aramco will consider re-issuing a tender for Manifa's development at a later date, assuming bids from contractors reflect a reduction in raw materials to match lower oil prices.

Such cancellations come at a price, which the article summarizes:

New oil-and-gas projects usually take several years of development before starting commercial production. According to Cambridge Energy Research Associates, the scaleback in exploration and production could reduce future global oil supplies by up to 7.6 MMBpd in five years, or 9 percent of current production. If demand suddenly comes back as it did in 2003-2004, there could be a resulting shortfall of production and much higher energy prices. The International Energy Agency (IEA) also warns that the credit crisis and project cancellations will lead to no spare crude oil capacity by 2013.

The longer oil prices stay low, the worse the shortfall will be due to the project cancellations and increasing demand. Incidentally, these factors also explain a big part of why the oil industry is historically cyclical; in the good times producers spend money, and then when supply gets ahead of demand and the price falls, they slow down on investing. This eventually leads to tightness again, so the good times return. The steepness of the World Oil Price curve in Figure 4 could be much steeper if demand recovers sooner rather than later.

The prospect of sharply higher taxes on the oil industry is a second factor that threatens to slow the development of new oil projects. A recent study by the American Petroleum Institute concluded that this number is "at least" $400 billion over the next 10 years. That seemed quite high to me, so I wrote to the API for a breakdown. Jane van Ryan, Senior Manager of Communications at the API, responded:

The figure is, according to our tax experts, “at least $400 billion” and could be significantly higher.

Using EIA numbers, our tax analysts have examined the impact on the industry of the administration’s cap-and-trade proposal using five scenarios. The results indicate that about 60 percent of the administration’s proposal, which would raise $645.7 billion in “climate revenues,” would be funded by the oil and natural gas industry. This means the industry would pay about $400-450 billion. We have opted to use the lower figure.

The industry’s share of business-wide tax provisions as well as new taxes on the industry are estimated at $80-90 billion over ten years. Again, we have opted to use the lower figure. These tax provisions include the reinstatement of the Superfund Tax, the repeal of the LIFO provision, internal enforcement/reform deferral/related tax reform policies, an excise tax levy on federal offshore leases in the Gulf of Mexico, the repeal of the enhanced oil recovery credit, the repeal of the marginal well tax credit, the repeal of the expensing of intangible drilling costs, the repeal of the deduction for tertiary injectants, the repeal of the passive loss exception for working interests, the repeal of Sec. 199 for oil and natural companies, the increase of the G&G amortization period for independent producers to 7 years, and the repeal of the percentage depletion for oil and natural gas.

While I won't get into all of the pros and cons of new taxes, higher taxes will provide a disincentive for projects which are projected to have a marginal financial return. If this further contributes to underinvestment, it will worsen the overall tightness in the oil markets, which will put more upward pressure on prices. Thus, high oil prices will likely again be a campaign issue in the 2012 presidential elections.

Conclusions

While the oil industry is historically cyclical, I believe we are approaching the point at which the industry will no longer be able to build out enough new projects to stay ahead of demand. This could manifest itself as peak oil, in which case the rate of depletion permanently overtakes the rate at which new production comes online. Or it could first manifest as peak lite, in which case new production still stays somewhat ahead of depletion, but can't keep up with new demand. In either of these situations, I think the historical cyclicality of the oil industry will disappear. In early 2008 I thought we had reached that point, but it appears that we had at least one more cycle ahead.

While it is too early to tell with a high level of confidence just where we are on the depletion curve, the summer of 2008 provided of taste of life in an oil-constrained world. The current level of underinvestment and the prospect of higher taxes are setting up another situation in which spare capacity erodes, leading to higher oil prices and greater volatility. Add to this the prospect of a global oil production peak, and I have trouble seeing a case where oil prices will remain stable in the coming years.

As an investor, I use blue chip oil stocks as a defensive measure against much higher prices. I am not one who subscribes to the idea that oil companies are going to be put out of business by running out of oil, or by ethanol, algal biodiesel, or any other combination of alternative fuel technologies. In fact, I strongly believe that if an alternative technology begins to look attractive enough, oil companies have deep enough pockets to shift their business in that direction. But I think that's unlikely to happen any time soon.

As a consumer, it would probably pay to evaluate just how much higher prices might impact your budget - and then take action. Can you sustain oil prices that return to $150/bbl or more? Even if you can, do you want that uncertainty hanging over your budget? If not, then it would be prudent to take steps to minimize the personal impact of high oil prices. Steps to consider include utilizing more fuel efficient transportation, public transportation, ride-sharing, and if possible locating closer to your place of employment.

Plan ahead and don't get caught off-guard like so many did last summer. It is only a matter of time before history repeats itself. Here's hoping our political leaders make policy decisions that won't worsen the impact.

I've been saying for a while now that it is going to be money, rather than geology, that is going to be the actual limiting factor for oil (and for all energy sources, actually) supply. Our national and global economy has entered the decline phase, and investment capital is going to be increasingly difficult to come by.

what if we backed out all the leverage/debt created since 1970s -how much productive capacity/ daily mbpd flow rates would we have? In the short run, fiat leverage not backed by biophysical reality CAN (and did) increase flow rates. But at what cost?

Since 'we' have started down the road, why not back out inflation in both the supply and the demand sides of the calculations and also explore purchasing power parity's effect on prices.

Since 2008 the world is a lot poorer - even in the 'rich' countries (particularly the rich countries). Not even America can afford $150 oil.

America ironically has a tremendous advantage in effecting prices because of seigniorage. Countries have to earn or buy dollars first then buy oil. This buying of dollars makes them more valuable relative to crude and restrains crude prices.

Refiners are on a knife edge. Margins are volatile. Two dollar gas will have more dampening effect in 2009 than it did in 2007. I expenct refiners don't want to get caught with a lot of expensive product they have to discount (below cost?) to move. Refiner angst is a restraint on prices. I can see this since Valero and Murphy oil refineries are literally next door - down the street. Gas prices at company stations swing a nickel or a dime between morning and afternoon.

What's left is wishful thinking:

http://www.marketwatch.com/news/story/oil-rises-3-traders-focus/story.aspx?guid={91EA1AC7-D81C-4B4E-8D44-B6B093A0C07B}&siteid=yhoof

I didn't propose to back out inflation, just debt/leverage.

Okay, do it!

:)

#126 on the list (but I might bump it up - it is kind of an important question - I think we widened the spigot of real energy flow rate by temporary magic (fiat leverage). Then when flow rate started narrowing again (on oil gas, coal, etc.), we changed the rules for more magic to go through an otherwise physical system (no doc loans, repeal Glass steagal, home equity LOCs, ,etc). Think about the implications of that. Seems that an unnatural widening of a spigot will result in a natural puckering as a reaction.

I've certainly suffered through several natural puckering events as I've learned more about both peak oil and our financial mess :)

I tend towards 'hair on end' rather than puckering. :)

It doesn't matter whether the limiting factor is geological or economic, no more than the exact timing of the historical peak matters. The fact remains that despite all the little spikes & dips, at low resolution the production curve roughly follows the Gaussian distribution and the world is at or near the apex. This is all most of us need to care about, as this is sufficient to inform us that our culture & civilization is in the process of becoming radically altered. The data isn't good enuf to waste time bothering about all the little blips, unless one gets paid for doing so. After all:

hoping won't do any good. the leaders are many and must come to a conclusion before something good will happen.

better just prepare for the worst. when the oil price will eventually explode again, it will seem like a walk in the park for some who prepared

I don't think so. I don't think that any amount of preparation is going to insulate anyone from the shitstorm that's brewing. We are in the midst of the sixth great mass extinction episode to have befallen the biosphere over the course of the Phanerozoic eon. PO is just going to exacerbate this anthropomorphic megadeath pulse. At best, preps will only prolong the misery. I could be wrong, of course, 'cept that I'm not.

Yes, because it is better if we engage in silly, unscientific, unfounded, abstract, unsupported hyperbole like this:

Flyby "silly, unscientific, unfounded, abstract, unsupported hyperbol(ic)" hit. Ouch!

Good that you can take criticism. As you said elsewhere:

Just as a gentle reminder, there are quite a few of us who want to approach this subject analytically and use a more formal approach. I have contended that our continued use of cheap heuristics works against us because we can never explain anything except by hand-waving. Yes I realize that bemoaning our plight is what most people care about here, but there are a small group of us who really want to understand this at a more fundamental level. No one else seems to want to do this.

BTW, I thought R2's analysis of Hubbert Linearization from a while back was fascinating. As he showed, you can engage in formal analysis simply by demonstrating contradictions in some heuristic formulation. We could probably work out a similar deconstruction regarding the suggestion of modeling the production curve as a Gaussian.

WebHubble- I'm one who wants to see more rigorous analysis. But it may not need to be much more complex mathematically. Thing is that rather than focussing our attention on the chart of gross barrels, more to the point is net joules. And EGOEI (energy gain on energy invested). (Or the related ERORI for the more traditional here.)

It's likely that EGOEI and ERORI have majorly reduced from the days of sticking a pipe in the ground in Texas. And even while gross barrels have continued to rise (prolonging the debate of whether peak is coming now or soon), my bet is that the more relevant net joules has peaked some years ago already, and the increasingly tightened EGOEI (along with EROHI, =energy return on human investment) is constraining investment (surfacely manifesting as credit crunch).

I don't have the experience/expertise to work out the sums on these questions. Might someone else here oblige us?

Well, what are you waiting for? Why not lead the way and be among the first to go extinct?

Thanks to OPEC getting their act together, and Russia showing signs of being past peak, the price has been stable these three months and starting to edge up. $54 a few minutes ago. This in the middle of the worst global recession in at least 80 years. For example, Ireland GDP 7% down yoy in the last three months. Industrial demand is down world wide, but consumer demand in the US for petrol is flat to rising, and in India and China it is still growing fast. Tata Nano cars get 65mpg, but they will replace 100mpg motorbikes, and in the gridlock of Indian cities they will be lucky to get 20mpg. We are burning almost as much oil, but using it less productively.

I think OPEC can successfully hold and push up the price towards $70 without difficulty. They won't want to go higher because they don't want to choke off recovery in the developing world. That would normally be more than enough to get investment going again, but this is not any normal recession. The credit crunch has made debt funded investment almost impossible, even of the oil supply. So the questions are, how much spare capacity do we really have, how fast will demand recover, how soon will the banks start investing in oil again, and, least knowable of all, how fast will be the 'depletion rate' of the existing oil fields.

('depletion rate' in the common sense of fall of pumping rate).

Where's that anal-yst that said oil was going down to $25? Not a month or so later and we are already more than double that...

Nick.

He probably hangs out with that kooky analyst who, when oil was $145, said it'd go to $300 within a year.

Bear or bull, it's all a roll of the dice, really.

Robert,

Do you think we might see a negative slope for the (pink) World Oil Capacity?.. or at least a dip as capacity tries to catch up with demand?

(I just don't see why capacity would increase if there's no profit for the driller.)

Robert, thanks for the excellent analysis. I think the peak lite idea is a good way to move past arguments over if we are at or past peak. You didn't really offer an opinion on the "new taxes" on the oil and gas industry. I see many of these as an elimination of tax advantages given specifically to the oil and gas industry, with the exception of cap and trade which is indeed a new tax. I think it is generally a good idea for the government not to pick specific winners and losers, but to let the market decide after taxes are put in place to account for externalities, in this case carbon dioxide. If this leads to higher prices and lower demand, I see that as a positive development which may lead us away from fossil fuels and towards alternative fuels and greater energy efficiency.

Dennis

While I agree that alternatives are a MUST if the world is to progress and not have a massive die off, the placing of carbon taxes by governments hurts everyone and especially the poor. Can you a imagine just getting by, only to get a massive increase on your heating or transportation bill? People could literally starve to death because of such madness. Add this to the fact that that additional tax revenue raised by a carbon taxes will not be spent efficiently due to politicians being corrupt or borderline corrupt. Private industry can solve the problem much faster and with zero burden on the people.

I agree with you about the impact of carbon taxes on the poor.

I don't agree that alts will have any impact whatsoever on avoiding "a massive die off," or about the ability of private industry to solve the problem any better than government can. The people in private industry this year were in government last year, & vice versa. Under Fascism, private industry & government are the same thing. Fact is, the problem can't be solved by anyone. Nature has to take its course.

In completely different roles. You seem to be missing the point of the free-market-efficiency argument.

Well isn't it at least possible that we can use electricity to fulfill most basic needs now done with oil energy? Why not? Do windmills suddenly not work post-peak? Yes, it won't give us three cubic miles of oil but that is a different argument from preventing die off.

It isn't that I miss it, it's that I think it's capitalist apologist propaganistic crap.

No, it isn't possible. Because all alt electricity sources combined can't even begin to substitute for refined petroleum products, especially not in the realm of transportation and especially not when there's no funding available for the massive buildout required to even make a dent, during an ongoing economic meltdown. Windmills quit working when there's no fuel for running the maintenance cranes & trucks.

More electric trucks

Heavy duty electric truck

Electric trucks

I'm concerned that taxes on carbon emissions get a little demonized in these discussions. A $15/ton carbon tax would raise energy prices far less than the increase in prices we have seen already in oil, coal, and natural gas from 2000-2008. The massive increase to which you refer has already occurred, absent a tax on carbon.

EDIT: Just for perspective, each $/ton of carbon tax adds roughly 1 cent/gallon to gasoline. Every penny counts, especially for the poor. But in the context of current taxation, or current price fluctuations (over $4.00/gallon middle of last year, down to $2/gallon now) a carbon tax is (in Europe) or would be (in the U.S.) a minor piece of the puzzle at the levels currently discussed.

A bit of a non sequitur. Why do you suppose 'private industry' (composed of people) has not yet availed itself of this 'zero burden' solution? Is it that crazy Gov't (composed of people) getting in the way?

I like the idea of progressive tax on energy, similar to income tax. Poor people can get x number of gallons of gasoline with little tax, enough to get them to work and back, groceries, etc. People that insist on driving their hummers to their cabin on the weekends can pay a huge amount of tax on some of their gallons. It seems fair to put an increasing tax burden on people that waste our precious fossil fuels. Same can go for electricity and natural gas.

The progressive carbon tax might be a nice idea, but would be difficult to implement in practice. The regressive nature of a carbon tax could possibly be offset by making income taxes more progressive. The increased tax burden due to carbon taxes could be dampened by reducing income tax rates on the low end of the income scale with an attempt to make the overall effect revenue neutral. In general the US has been moving to a less progressive tax structure so it is unlikely that a progressive tax idea will fly. I don't think alternative energy and/or nuclear energy will be a cure all, I do think they are a step in the right direction and the sooner we move on these issues the better.

Well,let me be more clear. Governments force people to participate(aka burden the people) in all manners of boondoggles while true FREE MARKET private industry gives people a choice to decide where their money goes. How many inventions have governments created in the past versus private industry? What societies tend to have the most advances in all manners of sciences and technology? The answer is in societies that don't over tax, don't over regulate,and don't suppress the entrepreneurial spirit that is the life blood of any advanced prosperous nation.

The problem is that unbeknownst to those entrepreneurs, they are being motivated by an eventually false goal - relative rewards in fiat money. Individual interest works great on an empty planet with few natural capital limitations and low population combined with ubiquitous trust in fiat (non-physical) currency perpetually maintaining a magic tether to physical reality. If fed prints another $50 trillion to bail out various industries, and ECB, BOE and others do the same, 99% of entrepreneurs will continue to work for fiat currency. What they really are competing for is social status, respect, and subconsciously moving up the mating ladder - when fiat money no longer becomes translatable into social advantage, we are going to have a problem with 'entrepreneurial' incentive. It will exist, but the collaborative temporal and spatial scales might be different than under a system that has just assumed that dollars/yen/pounds are perpetually translatable into stuff/power/fun/leisure.

As a gold/silver bug I agree that holding paper money long term is a very doomed prospect. That's why I convert my fiats to gold, silver, land, and companies that produce real things and pay dividends. People will always work as long as it worth their time regardless of how ridiculous paper money is. My motivation for working is not working in the future (retirement). Just as a thought, imagine a society without entrepreneurs? How would that society function and grow? I'm not sure it could function long term, well, at the least it would be like North Korea.

I've been pondering what the next few years are going to look like, and while I agree with the overall precept put forth, there are some details I want to raise for further consideration.

The biggest point is that it's pretty well accepted that the price surge we saw in 2008 was not solely driven by supply/demand constraints. While I do believe that 2008 will prove to be the year that peak oil actually occurred, it was not due to a lack of supply.

I'm quite certain that if the world were running at complete full capacity right now we would be producing somewhere in the mid 90mbpd. Of course we all know that the big question is Saudi Arabia. While some say that Saudi Arabia peaked as early as 1981, I will err on the side of caution and say that they have not peaked and still have spare capacity of 4mbpd and a max output somewhere around 12mbpd. Iran and Iraq also have to be put into the formula. The point I'm trying to underline is that while the world is at peak consumption, we could actually increase production. In other words, we're not being required to pump as much as we could.

As Robert points out, by the time we get out of this recession, supply from producers will have fallen too much and the excess potential of Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Iraq will not be able to make up the difference. This will cause the first real peak. By "real peak" I'm referring to the idea that economic growth will be stifled due to actual lacks of oil. I would expect this to happen no later than 2013. Until 2013 we will remain on the peak plateau where economic conditions limit our consumption not supply demand realities.

After this date we will see a meeting of supply and demand and the resulting world descent of oil production. However, I would also say that this descent will not be a general curve, but, as this simulated peak has presented itself, it will be a punctuated downward ladder with many little peaks with the resulting bust and burst economic cycles. Keep in mind though, none of these economic burst and busts will reach the production levels of 2008.

Any other ideas?

I don't understand the assumption that the economy has to rebound somehow to suffer the effects of constrained oil supplies regardless of the cause depletion, peak lite, lack of investment etc.

It seems to be and article of faith that we won't see oil prices increase dramatically until after we get some sort of economic rebound just like its and article of faith that oil usage will continue to decline as the economy declines.

Oil usage during the Great Depression did not decline during the entire depression. During our own recessions oil usage initially declines then rebounds often close to the "bottom" of the recession however recession bottoms are not a return to growth but a point at which excess capacity has been pulled back and investment redirected into the remaining profitable businesses unemployment continues to increase well after the bottom of a recession.

Basically you get a number of dead cat bounces around the bottom as the economy becomes more efficient and sheds unproductive businesses but this is not growth. In the past during recessions these bounces eventually catch and you return to growth but its not required.

I see no reason that we won't simply basically bounce along the bottom economically with no recovery and that real depletion won't eventually become evident or continued lack of investment result in a investment driven peak. Anyone that can make money burning oil can and will regardless of price as long as they can pass on the costs. So oil usage need not decrease and in fact should either be flat to slowly increasing going forward regardless of the price of oil.

The main point is there is absolutely no reason to expect any real economic recovery as a precursor to high oil prices and I see no reason for oil usage to change dramatically if prices begin to rise regardless of the state of the economy until they reach a intolerable level but I'd argue that the intolerable level for a economy that has had a significant amount of its unproductive features if you will may be much higher than a economy at the tip of a bubble.

I'm not saying that it might not turn out that way but for now I'd suggest that the combination of depletion and slowing investment probably means that our economy will never recover and will simply grind down with ever higher oil prices. The net effect is wage deflation and an ever growing mass of poor to desperately poor people that no longer can find any job. So my opinion is we will simply see our economy transition directly into third world style economics with limited expensive oil resources. Next I suspect that this case of and obviously sick economy thats degrading coupled with high oil prices will continue to work to damped the incentive to expand production pretty much regardless of price signal.

High oil prices and and obviously sick economy simply won't cause investment in expansion of oil production. At some point and I suspect this point is already in the past depletion will ensure that its too late to grow oil production and a belated expansion attempt cannot stop the spiraling economic transition from first to third world for the major economies. Again this does not mean demand ever drops enough to result in low prices again it just means that we get true demand destruction. The price of oil remains high and as overall supplies decline we simply kick more people out of the life boat if you will leaving those that can still afford oil.

Seems to me that it's a matter of timing. No economic rebound & oil prices creep back up gradually. A temporary rebound and they spike again. Either way they're bound to go back up. Economic factors confound the picture at fine scale but by & large it's geology running the show.

Again no reason to assume they creep back up with no rebound.

We can use the collapse of the Soviet Union as and example they entered economic collapse and oil production collapsed even though its obvious that if they had maintained their previous production level or worked to slow the decline they would have gotten far more external capitol entering their economy lessing the economic collapse. Given the importance of oil to the overall Soviet and then Russian economy why did they simply leave the money in the ground ?

They left it because the economic environment could not support continued production much less expansion despite the obvious benefits of maximizing oil production.

I suggest that the world is entering the same conditions as the Soviet Union did during its collapse oil production will fall sharply under the combined effects of both depletion and economic pull back and oil supplies will drop rapidly. Worse I suspect we will see the export land issue worsen as oil usage internally in these countries is maintained and even increased to prevent internal collapse. Total oil exports should decline dramatically this year no slow decline.

Now I could be right or wrong but my point is that the basis that people are using to either predict that prices are low until we have and economic rebound or even to predict that we can't have a sharp spike in oil prices but a slow increase really don't have a firm fundamental basis. In fact we actually have a known example of the Soviet Union that if applied to the global oil supply and adjusted for exports predicts the exact opposite that instead we should see a sharp spike in oil prices.

Just the fact that I can present what I believe to be a compelling argument indicates that the scenarios outlined need a lot of work. I'd argue that the first order of business is to disprove a global soviet style collapse coupled with export land and associated sharp price increase with production continuing to decline.

Lets dismiss the worst case scenario first before we predict milder cases. So far at least I'd argue the future of oil prices is yet to be decided and the overriding factor is the current supply glut only after we see its decline rate which could well be zero can we even begin to understand how prices will move. And we could just as easily have a mild recovery for a ordinary recession some recovery factors have already kicked in companies that downsized early are now more profitable for example even if their revenue has fallen.

In cases such as Best Buy vs Circuit City the failure of competitors increases market share and gives a slight boost to the overall profitability. Simple economics dictates that some isolated economic indicators effectively at the individual company level are now positive.

In general this is what differentiates a recession from a depression and indeed in the Great Depression economic indicators individually turned positive many times as the entire economy continued to decline. Oil usage in particular and even car sales went positive well before the final end of the Depression.

However my argument is fairly simple massive investment in oil even to maintain our current levels will not happen as long as the overall economy is contracting regardless of the price of oil or the demand levels. In a deflationary depression there is simply no money to invest in expansion no matter what you do much less maintenance in a industry in decline.

Looking back at the Great Depression one can see that the agricultural industry suffered a fate similar to what I'm talking about. Again its different from oil but it shows a critical industry in distress during and economic downturn.

This is Kansas and it suffered the dust bowl.

http://www.oznet.ksu.edu/WHEATPAGE/Links/whetprod.html

But I've argued we have our own dust bowl like situation for oil because of technology.

You can look at lots of different commodities but in general during a sharp economic contraction production also contract sharply and does not resume growth until the economy actually turns around. And for oil historically after demand from growth is eliminated further demand reductions slowing rapidly then with demand bottoming and recovering before the economy recovers back to its old levels.

The historical record does not offer a perfect precedent but I'd argue that everything I've read points to my worst case scenario as the most plausible one.

Aren't we already seeing it happen though?

It seems that drop in usage at worst would track drop in employment rates. In other words, as long as people have jobs they will still demand/use close to the same amount of oil as before, minus some conservation measures. And the unemployed will still use some. What kind of drops are we anticipating after all?

Here is an example of an oil shock model undergoing a sudden 20% drop in extraction rate from reserves

Note that even 25% doesn't make that significant an impact in the long run. So a rise in demand pressure is always near as we cannot easily affect the stochastic arc of decline.

A simple review of VMT for the rust belt and the city of Detroit shows that persistent economic decline and high unemployment rates does not correlate with a dramatic change in per capita oil usage in the US. I've posted every paper I can find on the subject.

You can look at Kansas one of the powerhouses driving the US economy as and example.

http://kec.kansas.gov/chart_book/Chapter10/04_AvgVMTperCapitaKSandUS.pdf

Here is some of the per capita data it can be found for all states and years.

http://www.bts.gov/publications/state_transportation_statistics/state_tr...

I don't see a strong correlation between unemployment levels and overall GDP for the state and VMT. I'm not saying that it does not go up and down a small amount as the economy changes but you can takes states that vary by as much as 10-20k or 30-50k in median income and per capita VMT is not correlated with median income.

And last but not least another big factor in oil usage hidden in the VMT data is congestion effects our roadways today are significantly over croweded and traffic flow patterns are horrible. Plenty of info exists on congestion but I've not found hard numbers on how it effects overall oil usage per mile or the real mpg with congestion. In general it lower the efficiency of travel vs nameplate efficiencies.

Here is one probably slanted study.

http://www.greencarcongress.com/2007/09/study-traffic-c.html

Given that most of the congestion occurs from work traffic we can assume that even as VMT fell congestion itself continued to play about the same role as before thus VMT declines probably overstate the drop in demand.

Given that most of our road beds carry almost four times their designed capacity we would need to see a much larger drop in traffic levels before congestion clears.

At some point in the future we may well get a small Indian Summer if you will as congestion drops clear the road ways and increase our net fuel efficiency. Given the extreme overload and the high probability that our roads will continue to deteriorate and expansion will be curtailed and population growth continues I'd say the chances are slim.

This is not to say short term shocks won't effect oil usage but the data seems to indicate that a 3-6% change is probably about right since oil usage per capita seems to be only weakly tied to either income levels or unemployment levels. Demographic changes in various regions seems to be more of a factor one reason Wyoming stands out for example for per Capita VMT. It seems that people drive most often because they have to not because they want to.

Well, a 3% to 6% reduction is essentially inconsequential. You know this and I know this but not a lot of other folks do.

LOL :)

However the second derivate can cause a short term oversupply. A 3%-6% drop over a period of six months is a big short term hit.

Off hand I'd guess a pop if you will like that has and effect say double its magnitude.

And in our case most of the drop was even shorter 3 months. So a fast drop can probably at best cause a ripple if its 3-6 months out 12 months before fundamentals take over.

So yes your right but also the model in a sense places constraints for how far short term events can extend before being overwhelmed by fundamentals.

Look at the figure and then imagine the effect shown is 1/3 to 1/6 the magnitude. I maintain that is nothing for the out-years. I guess this isn't as obvious as one would imagine.

Looks like a significant difference to me since it affects two different kinds of hardship. The supression can be handled by less discretionary spending, vacation air travel, and moving closer to work etc while the saved resources allows more long term investments and less hardship when the situation forces harder prioritizations.

If a lot of the savings are used for long term investments you even get a new steady state that might be comfortable. This work should of course have started in the 70:s at least but there are no time machines.

I don't believe Manifa has been cancelled, as your source suggests. This is from the 17th, a day later than the Apache article: Middle East petrochemical project activity slows down

An out-and-out cancellation would make for quite splashy headlines.

This piece also points out the interesting fact that Ras Tanura's primary source of credit was to be RBS; Saudi Aramco and Dow are now shopping for a new bank, of course. There's a limit to government ownership of a firm, beyond which other governments will balk at doing business with said firm, thus the spectacle of partial takeover of AIG and the like.

Robert: could you plot inflation-adjusted price against spare capacity? (I am new around these parts; maybe it has been done already.) That would greatly bolster your case.

I know Robert is traveling. I'm sure that has been done but unsure where. You can search by keyword or click on any authors name to see a list of stories/analyses over past 4 years. The amount of stuff lost down the rabbit hole here, is staggering. But I know of no better way.

I'm not Robert or Rembrandt but here's my feeble attempt:

Damned if I know where Rembrandt gets that country-by-country breakdown of spare capacity. Had no luck finding it at either EIA or IEA, but this data is from the latest Short-Term Energy Outlook, and Historical Crude Oil Prices Table from inflationdata.com.

OPEC may have as much as 4 million barrels in spare capacity. If you get a bounce in the price of a barrel of oil to $100; OPEC might increase oil production same as last year. U.S. domestic oil production grew 5.3 percent YOY as of this week's EIA petroleum report. Total petroleum products supplied down 3.2%. Oil inventories at their highest levels in more than 15 years. Sort of nice not to have to worry about peak oil today. Tomorrow will take care of itself.

I created a simple model along the same line in Excel -using some simple Supply / Demand equations and a simple price Func().

I got this output (again don't pay too much attention to the dates/prices, just the overall shape).

-What was noticable from the model was that on the increasing side the sell-offs where much further apart, demand took longer to reach increased supply. On the downside demand hits reduced supply much quicker. This led me to think that 'recessions' -in this model- would come at ever closer intervals as supply decreased...

[Edit: I also think that the idea that $150 oil is somehow 'outragously high' is laughable, clearly it causes issues, especially in places that are highly leveraged to cheap Energy but it is not 'too high'. Demand remains for this 'wonder product' if you can call it that and b4 too long these prices will return...]

Regards, Nick.

Basically this is the same argument I'm making.

I'd argue that you see no recovery and no slow increases in prices with your model.

Whats important is these two common sense solutions if you will don't seem to be present.

I believe that you are assuming a finite supply of dollars in your calculations. The Fed will make sure that that there are more dollars in the system chasing less and less oil. A lot of these dollars have already found there way to China. More dollars + less oil = inflated oil prices = demand destruction. We are basically in a feedback system that appears to have no end. It also has the possibility of going exponential

I think the upward trend in prices from your Figure 3 is highly likely, assuming that demand begins increasing again in 2010. My updated forecast, for the IEA OMR Mar 2009 report, shows a similar upward trend for average oil prices. WTI oil could reach $100 by the end of this year.

http://omrpublic.iea.org/

OPEC cuts are helping to push prices up. As prices increase, some OPEC members will probably increase production causing world liquids supply to increase up to about 84.5 mbd in the first quarter of 2010. Afterwards supply is likely to decrease as non OPEC production decline rates accelerate.

http://www.theoildrum.com/node/5125

If there are supply shortages due possibly to terrorist attacks in the Middle East OPEC countries then Matt Simmons' recent statement may come true. If demand doesn't drop further and there are no significant supply disruptions then the next oil price shock is likely to occur in the middle of 2010.

http://www.reuters.com/article/reutersComService_3_MOLT/idUSTRE52P2D6200...

click to enlarge

For more information about declining world oil production

http://www.theoildrum.com/node/5177

Ace - magnificent chart but there's something strange about it. The (your?) forecast prices go up and down with demand excess (as one would expect). But in the historical section there's no such relationship evident. Any suggestions?

The EIA has some very interesting information that agrees with your thesis.

Take a look at:

Typical Economic Relationship Between Surplus Production Capacity and Price on page 15

http://www.eia.doe.gov/pub/oil_gas/petroleum/presentations/2008/oilprice...

As an investor, I use blue chip oil stocks as a defensive measure against much higher prices.

I avoid "blue chip" (i.e. major) oil companies as they are likely to be poor performers compared to other oil companies.

I see substantial ownership of refineries, chemicals and pipelines as significant negatives and likely money losing divisions post-Peak Oil. I also see US based and US assets as negatives. Majors also have excessive overhead.

I see partial state ownership as a positive (StatOil Hydro, PetroBras, GALP ?) since it provides political protection. They are also less likely to do irresponsible things that later come back to haunt them (Texaco in Ecuador).

The only US oil company I own is Apache (world's best potential for enhanced oil recovery from depleted fields). Tullow has excellent African developments and some Indian. GALP is junior partner with Petrobras on several major finds and is the only company invited into the Venezuelan Orinoco heavy oil play by Hugo Chavez. Encana & Canadian Natural Resources provide some diversity with North American natural gas and oil sands exposure.

All companies noted have significantly better management (a strong positive post Peak Oil) than, say, Exxon Mobil.

Best Hopes for an Optimized, and diversified, Portfolio,

Alan