How Fast will China's Oil Demand Grow?

Posted by Gail the Actuary on July 7, 2010 - 10:30am

This is a guest post from Steven Kopits. Steven heads the New York office of Douglas-Westwood, energy business consultants.

In my last post, we looked at the supply of oil in the US Energy Information Administration's (EIA's) recently released International Energy Outlook (IEO), which many consider the EIA's definitive annual forecast. This time, we look at the demand side, specifically China. Since the IEO is a government report, many business organizations rely on its forecasts.

Oil demand does not grow linearly with GDP. Rather, the bulk of oil demand growth occurs in the two decades during which societies typically acquire motor vehicles, after which per capita oil demand flattens. For example, per capita oil consumption in the United States is today lower than it was in 1979, even though per capita income has increased substantially since.

Demand levels attained in emerging economies are relatively comparable regionally. For example, per capita consumption in both Korea and Japan peaked at 1.9 U.S. gallons per day. Korean levels are unchanged; Japanese consumption has declined to 1.4 U.S. gal per person in the last decade. (For purposes of comparison, US consumption will be about 2.5 gal / day per capita in 2010, down from 2.9 gal in 2005.)

Both Japan and Korea are effectively islands (Korea due to its closed northern border), and both are densely populated, mountainous Asian countries. In fact, South Korea's population density is three times that of China. As a result, Japan and Korea's per capita oil consumption is comparatively low next to that of countries with large land masses like the United States, Canada and Australia. China has a land mass equal to that of the United States. On the flip side, China has a one-child policy, which may reduce the need for suburban housing.

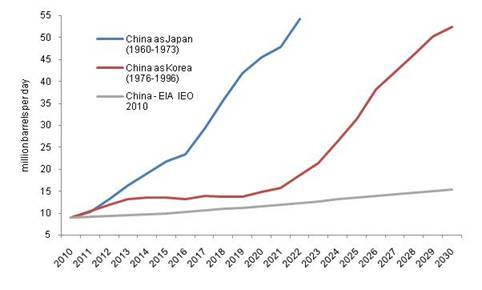

In any event, without delving deeper, we might expect China's steady state demand for oil could prove not less than that of more advanced Asian nations. Based on the experience of Korea and Japan, China's current population would be expected to consume approximately 55 million barrels per day at steady state (when per capita consumption plateaus), or nearly 2/3 of current global oil production, were the supply available.

This increase in demand can arise quite quickly. Japan's oil demand increased six fold in the twelve years prior to leveling out. Demand can also develop more slowly. In the case of Korea, a six-fold increase in consumption required twenty years, with much of the delay owing to OPEC pricing strategy following the second oil shock of 1979. Korea's model of development is potentially relevant for China, as China faces an oil price environment not entirely different from Korea's after 1979. Importantly, high oil prices from 1979 to 1985 did not destroy Korea's demand for oil. It only deferred it. Thus, we might expect that, were oil prices to fall substantially and durably, China's demand for oil could surge fairly quickly. Indeed, were the oil supply available, China's consumption could increase by more than 40 million barrels per day by 2022.

Source: EIA, EIA IEO 2010, Douglas-Westwood analysis.

In contrast, the EIA sees China's oil consumption at only 10 mbpd for 2015, a growth rate of approximately 2.7% from current levels, and at only 16 mbpd by 2030. Is this consistent with a country whose vehicle sales are up 56% in the first five months of the year? Where sales of Audi's are up 77%, and those of BMW have doubled compared to the first five months of last year? Is China truly going to be satisfied, as the EIA would have it, with less than 1/5th of the per capita oil consumption of Korea in 2030, even though they should be similar by that time?

The differences in views about China's oil demand outlook have enormous policy implications. If the EIA is right, and China will forget how to grow, then pressures on the oil supply will be modest. On the other hand, if China is to develop like other countries in Asia, the pressure on the oil supply will be crushing, with oil shocks, recessions, and war all conceivable outcomes. The energy--as well as the economic and security--policy differences between the two scenarios are like night and day.

Is the EIA sure it has the numbers right?

Thanks, Steve!

There are lots and lots of people in China. Clearly, if conditions were right, the people would like cars too.

Aren't roads awfully crowded already? It seems like a lot of paved roads would be needed before demand could grow very much. Or is some of the demand you are forecasting for things like asphalt, to pave roads?

Remember that cars are, among other things, status symbols. I have heard reports that some of the newly wealthy are getting cars just to have them sit in front of their houses for people to see.

That may be true of a tiny minority, but the vast majority of cars are bought to be driven. Even in Europe, with some of the highest fuel taxes in the world, the cost of petrol is negligible compared to the price of any vehicle which could be remotely considered a status symbol.

( I use 300 gallons a year. That is about £1500 or $2,300 a year. The car costs me at least that much or more in taxes, insurance, and depreciation. It was a cheap second hand car.)

In the UK, new cars are driven more miles than older ones.

I expect each new car will be driven 10,000 miles a year.

...even so, I am much more impressed by how few cars there really are in China, and how well built the infrastructure is for alternative transportation. I wonder if this whole conversation is not skewed by our car-centric perspective. What if China in general looks at us in our big oily self-dug hole and thinks "hmmm, lets not do that". What evidence is there that most Chinese even want cars?

One thing I saw recently is encouraging - while conventional bicycles may be declining there, the electric bicycle business is booming, and far outstripping car sales (http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1904334,00.html). From our perspective, we tend to see that as a temporary recreational or transitional thing - "of course they'll all want real cars, as soon as they can afford them". What if that's not the case, what if they're a little smarter than that?

I was in Xi'an (2nd biggest city) two years back. I wouldn't have said that alternative infrastructure was more prioritised than road travel, it was just that there was lots of building of all kinds. Also, relative to a comparably important British/American city the car traffic density was significantly less, so the problems were less obvious. So I haven't seen any evidence that the people themselves have decided that cars per se were not something that you wanted. It's just that the relative cost of a car vs an electric bicyle means more bikes are being bought, but if they get even more affluent I can easily see those bikes being traded in for cars.

Of course, I don't know anything about governmental views about cars vs the alternatives, which is where things might be different (particularly if they're prepared to weild central control in unpopular ways).

...of course as a cyclist I may have a skewed perspective myself, but cycling in the US is a marginal or minority activity much as driving in China seems to be a marginal or minority activity.

Perhaps awhile back the Chinese would have looked over and wondered when we were going to get tired of our impossibly expensive and dirty cars, just as we looked over and wondered when they'd finally get tired of riding all those bicycles. There's always a percentage of people who'll form a minority group against any trend. In the US, I happen to be a cyclist in the minority.

In China, what is the real trend? As mentioned, E-bikes are selling 4-1 against cars, and the number of manufacturers is staggering. Looking at an exponential progression, you don't have to go out very far to say China could remain a cycling nation, with cars present but in a permanent minority.

I think, the way things are trending, Chinese consumers will buy new cars, and then leave them parked most of the time while they ride their E-bikes. They will use the cars to go places they can't go by bike, and to take weekend drives with their (one child) families.

Unlike most Americans, they aren't forced to drive everywhere they want to go, and they won't do so because they can't afford the fuel. However, they can afford to drive when they really want to drive, and that is going to consume huge amounts of fuel. Individually, it is not very much, but collectively it is a lot.

I was in Chinese-dominated Singapore in 1987. Not only was everyone buying cars with a 100% import tax tacked on, but the superstitious Chinese were bidding against each other for lucky license plate numbers, up to thousands of dollars. Then they all got to sit in horrible traffic jams while under their feet the cleanest subway system I've ever seen went empty.

Beijing better find a better status symbol for people to waste their money on, because they will definitely waste it on status symbols.

This is the sort of thing that makes me pessimistic about people voluntarily adopting transit on enough of a scale to matter, in the comparatively empty, wide open spaces of, say, New Jersey, never mind the bulk of the USA. Even in an island city-state, you still have to walk to the station in steaming, sultry humidity, wait a random time for a train - Singapore schedules are apparently state secrets - and get even more soaked during the walk in the steam getting from the train to the final destination. No wonder they wanted cars no matter the expense (owing to horrific taxes), even if by US standards there's nowhere much to drive them...

Gail,

If you click on the China tag on this key post, you will immediately see Stuart's key post on the growth of transport infrastructure in China.

http://www.theoildrum.com/node/6126

They have built a lot of roads in the last decade - more than 60,000 Km of expressways. They probably exceeded the total length of USA freeways this year 2010.

There is clearly room for growth on the roads. With only a tiny wealthy percentage of the population currently owning cars, the total car ownership (and hence miles driven) still has room to grow substantially even if the economy overall stalls or even declines. There is already a lot of unmet demand for car ownership in the middle income bracket. Once they have been bought, the cars will be driven.

Obviously exponential growth cannot continue for ever, or even another decade at the rate China has been expanding, but there is still room for oil demand to maybe double or even double again short of a major collapse.

The only thing I can see curtailing continued oil consumption growth is the imposition of very severe rationing by the central government. China is probably the only country on earth that the government could impose such rationing and survive, but it would be a last resort, even for China.

Wow, just looking at that chart is a shocker! By 2012 if things stay the same, China will be consuiming between 12 Million to 15 Million barrels of oil per day. That's 4 - 7 Million barrels more than it is consuming today. Where on Earth are they (the big oil companies) going to find 4 - 7 Million barrels per day in about 2.5 years?

Whopper of a chart! And what about India, Brazil, other emerging markets? Could easily be 10 Mn Barrels per day in extra demand by end of 2012. No way that's going to be met with production having peaked.

Looking at the graphs, I would say it will be a decade or less before China is consuming more oil than United States.

This has serious implications for the United States, because the Chinese will probably outbid them for the world's scarce oil resources. The US will need more imports as a consequence of reduced offshore domestic production after the BP blowout.

Less so for China, because China is already having great success buying up the world's oil resources, and the Chinese people can easily go back to walking, bicycling, and mass transit if driving gets expensive.

I don't think US policymakers have thought about this. The Chinese apparently have.

How could the Chinese private motorists hope to outbid the US's? I don't really see it happening any time soon.

It's not the Chinese private motorist but the Chinese state oil companies that will outbid the US. And they will use US dollars to do it.

The individual will buy a much more fuel-efficient car, and will drive much less, but there are four times as many people in China. That's the key issue.

Depends on what you mean by "outbid", I guess. The fact that China is getting any oil at all means they are "outbidding" some marginal consumption in the rest of the world.

China will clearly improve on this, aquiring a larger and larger portion of the world oil production. However, they do have a nominal per capita GDP merely a tenth of the US. They won't ever outbid the US in the sense that they will have a larger per capita oil use.

Drivers in developing countries can outbid US drivers by doing the following:

1. They have a lower cost structure. Most people live with their parents all their life. It is not uncommon for 3 generations to live together. They often don't have day care/child care expenses.

2. They have very little or no debt.

3. They don't have large homes that are expensive to heat, cool or maintain. Property taxes are negligible.

4. They drive smaller, fuel efficient cars.

5. They don't drive as much as US drivers.

The problem in the US is that most people have a large, unsustainable, cost structure that often comes under strain when energy costs go up.

An average American is a lot more wealthy than an average Chinese or Indian. But do not forget that the top 100 million Chinese and the top 50 million Indians are easily more wealthy than the bottom 80% of the US or European population.

All this will tend to equalize along with increasing oil use. I'm curious if you have numbers to support the 10%/80% claim. I have a hard time accepting that one.

"There are none so blind as those who will not see."

Relative to 2005 consumption levels, the predominant pattern is developing countries effectively outbidding developed countries for access to global net oil exports. I don't expect to see this pattern changing.

In that sense, I agree. As the developing world gets a greater share of global GDP, they get a greater share of the oil.

The Chinese have been and continue to invest heavily in infrastructure, including roads. I was in Beijing a couple of months ago, and I have to tell you, the roads are superb. Probably the best of any city that I have visited. Of course, much of this was the result of the Olympics, but at least regarding their roads, the Chinese spent their money wisely.

The national car of China, at least in Beijing, is the Audi A6. There may be some political connection there, but I was frankly surprized by the variety and quality of many of the cars on the road. Many BMW's, Mercedes, and relatively few purely Chinese models like the Cherry. Mostly Toyotas and other Japanese brands, as well as some US brands. But if you eliminated most of the SUV's, the range of cars in Beijing was not all that different from what you'd see in the US.

The roads were not nearly as crowded as I expected. They've added or upgraded ring roads around Beijing, so traffic, at least when I was on the road, was never as bad as, say, trying to get to JFK Airport from midtown Manhattan. And remember, car ownership in China remains low. In any event, I saw nothing there that would convince me that China's demand for oil would be less than Korea's or Japan's.

China is key in the peak oil story. While the Oil Drum and ASPO tend to focus on the accounting peak for the oil supply, in reality, the economic impact is a function jointly of supply and demand. Peak oil, in economic terms, is already relevant when supply can no longer keep up with demand, not only when supply actually falls. Best I can tell, demand started outstripping supply in late 2004, and I see nothing to turn that around in the future. When the oil's available, China will take it. Policy makers need to understand that.

"Chindia's" combined net oil imports rose from 4.6 mbpd in 2005 to 6.0 mbpd in 2008 (EIA).

Expressed as a percentage of the combined net exports from the (2005) top five net oil exporters, Chindia's combined net oil imports rose from 19% in 2005 to 27% in 2008. If we extrapolate this trend, then by around 2019, Chindia would be (net) importing the equivalent of all of the combined net oil exports from Saudi Arabia, Russia, Norway, Iran and the UAE. This is about the same answer we get if we simply extrapolate Chindia's rate of increase in net oil imports, versus Sam Foucher's projections for (2005) top five net oil exports.

My outlook for the US is that we are well on our way to becoming substantially free of our dependence on foreign sources of oil--as we are forced to make do with a declining share of a falling volume of global net oil exports.

India will not catch up to China. For a variety of social, religious and political reasons, India will be unable or unwilling to develop and deploy its human resources with the same degree of diligence and organization that China will muster.

Confirmed - travelled through both a few years back. India has some rail going for it, but you don't want to travel by road - no 'highway' to speak of, and seemingly not much development on that front. A few hundred kilometers could take all day and shake your eyes out in the process. China = infrastructure on the other hand. Massive projects underway all over the place.

It is interesting to compare China's demand growth with e.g. Saudi Arabia's oil production

I did that here by using the IEA 2007 demand estimate:

9/11/2009

World needs to save at least 3 mb/d by 2020 for China to grow. Any volunteers?

http://www.crudeoilpeak.com/?p=525

One might add Singapore for an impression of large sways, if not all, of future China. Barring major disaster, that is.

Natural Gas Vehicles have been picking up recently there. They are mature technology and China has reasonably good access to natural gas supply from abroad. World reserves are not an issue for the time being. Also anaerobic digestion technology is maturing rapidly and provides for one of the better biofuels.

India may have the bigger headache with liquids over the next 10 years.

If I have my numbers right, NGVs use some 40 megatons of oil equivalent of natural gas per annum right now (about 1 million b/d). Now the question is how much that will be by 2020.

China had already petrol and diesel shortages in 2005

http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/english/doc/2005-08/18/content_470149_2.htm

That's why they imported an extra 800 kb/d in June/July 2008, shortly before the Olympic Games, to avoid shortages. That drove up oil prices to $147 and broke the camel's back. Saudi Arabia couldn't deliver, twilight in the desert.

That gives us a foretaste of future demand surges in China. I hope they will never have a soccer cup there.

It's hard to imagine any alt-energy deus ex machina for China that gets it off of oil imports and domestic coal. They have deserts, but too far from the population for transmission lines. They have wind turbines, but none of the ideal places to put them. They don't have serious tidal or wave power potential. Their population is concentrated on the south coast, where you have typhoons, earthquakes and overcast skies. I would really hate to see a nuclear accident near Shanghai.

I'm pretty much down to growing seaweed on every inch of their coastline.

> It's hard to imagine any alt-energy deus ex machina for China.

Not a perfect match, but Iranian liquids demand has been increasing at roughly Chinese pace recently. Last year it went down and natural gas went up by 10 percent.

It is hard to see anything that isn't hard in China energywise.

Here's and angle to ponder: The development of the Alberta Oil Sands as a socially and politically responsible endeavor to foster world peace. Before anyone goes off with their firmly held opinions and beliefs, remember they are just that, opinions. Leave all the enviro-speak aside for a moment and consider the wars and misery.

It would be safe to say the current conflicts around the globe are centered on hydrocarbon energy sources. If the Oil Sands has more reserve capability than Saudi Arabia at current price levels as a floor (which they do), then would it not be in the best interests of all oil importing nations to accept this source in the name of reduced tensions and conflicts? Furthermore, the Oil Sands should be developed at a pace that tends to put upward pressure on the price so that the supply-demand curves drive responsible exploitation.

BTW, I don't have any interests in the Oil Sands and this is not a pitch. Based on the article's analysis the growth of China is only going to put more pressure on existing oil supplies and we need to create a "relief valve".

Some of the recent reserve amounts announced are probably PR stunts, but let's give them the benefit of the doubt for a moment:

http://www.e-tenergy.com/et-dsptechnology.php

Furthermore, there a quiet plans afoot to supply the electrical energy in the Oil Sands area using renewable sources from BC. Now there I do have an interest. So looking at the counter argument to more extraction of FF sources in an effort to reduce GHG emissions, would it not actually be in everyone's interest to encourage the development of expensive sources in benign areas thereby ramping down FF consumption? With the proviso existing cheap sources (i.e. coal) are legislated out of use eventually.

The Chinese already have bought up large amounts of oil sands capacity, and they're interested in buying more. They're quite subtle about it, they never buy more than 49% of a project, and they usually buy out some foreign (usually American) company so it doesn't trigger a Canadian foreign investment review. The Canadian government is indifferent to foreign companies buying out other foreign companies, and it doesn't really care whether the oil goes to China or the US.

US politicians really should pay more attention. Recently 50 members of the House of Representatives signed a letter to the State Department opposing a pipeline to carry Aberta oil sands bitumen to Texas.

OK, guys, if you block oil from Canada, and you ban offshore drilling in the Gulf of Mexico, where are those Texas refineries going to get their oil from? Certainly not Texas, given its production declines in recent decades.

OTOH, the Chinese are promoting a bitumen pipeline to the Northern BC port of Kitimat, directly across from China, and putting in a dock that will handle the world's largest oil tankers. They have a pretty good idea of what those Chinese oil demand charts mean.

"OK, guys, if you block oil from Canada, and you ban offshore drilling in the Gulf of Mexico, where are those Texas refineries going to get their oil from? ......"

How about that guy in Venezuela, I think his name is Chavez? Oh, I forgot, he just nationalized several US company owned oil drill rigs and China has bought a stake in Venezuela's new oil production in Orinoco basin. Maybe get some oil from Brazil's Tupi presalt and subsalt formations? Oh, thats right, China is making deals with Brazil too. Well, then maybe Sub Saharan Africa? Oops, China just entered into new deals for developing fields in Uganda, Congo and (IIRC) Nigeria too.

Well, Texas has a lot of wind potential, so maybe they can synthesize the oil from beef fat using electricity, lol.

Thanks for the laugh, I needed it.

Thanks guys, you just made my argument for me. Exactly that is what is going on. I have doubts about the success of the Enbridge pipeline across northern BC (midway actually if you look at the map), but that oil is going to make its way to the west coast for shipping one way or another.

FYI for the Tooders, its a two-way pipeline system. Diluted enriched product going west, and the dilution liquids extracted at the destination refinery and pumped back east for further use. I think the light fraction is either naptha or butane, but the petro-engineering crowd can clear that one up.

The reverse-flow diluent pipeline is likely to carry natural gas condensate sourced elsewhere in the world. They're planning to build a separate dock at Kitimat for the condensate tankers. Alberta has a bit of a condensate shortage as the result of demand for it as a bitumen diluent.

Over the next ten years, China will emerge as the foremost economic power on the planet. Chinese consumption of all types of fossil fuels will outstrip all other nations. Chinese usage of coal and oil will dictate the future price and supply of these energy sources as well as all other energy sources including uranium.

The Chinese sphere of influence will grow to dominate areas of world energy production especially the mid east and Australia. Russia will increasingly sell its natural resources including coal, oil, gas and uranium into the Chinese markets.

The direction of CO2 world production will increasingly rest in the hands of a few top Chinese policy makers. In the hands of these few men, will lay the consequences of peak oil, coal, and uranium and their eventual resolutions.

It is pretty hard to dictate something to 1.4 billion, as the mentioned people could probably testify. Optimization processes tend to take over naturally as long as you remain within bizness as usual.

It could be called the law of very large numbers.

Thats why one could see Mao swimming in the Yangtse btw. Also the proverbial wise man who doesn't want to live in interesting times springs to mind.

Check your opinion against this article:

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/05/business/global/05warm.html?_r=1

Good piece. This go at it may be only be indirectly on-topic, so please skip the following if you only worry about oil demand.

Even though it mentions gas mileage, the article also strengthens my views that electricity and heating are among the more challenging problems China is facing ATM (who knows what will be in ten years?) once you abstract from the instability issues with current international commodities marketplaces. Over the last five years (04-09) demand for fossil liquids has increased only at half the pace of the rest of energy. For 09 it stands at 17 percentage points compared to 38 for the "addicted" country.

Much of their development has both been from a very poor state and at a neckbraking pace. Understandably there's dirty and inefficient power generation, poor industrial processing, and bad housing. Staying with energy, the jump in demand for this winter and spring mentioned by the article is due though to very low numbers the year before from the global economic shock freeze and their subsequent economic stimulation. Unfortunately that does not mean that the growth of energy use will slow down. Spanish energy thirst for instance has only weakened very recently.

Whatever the fate of their savings efforts, electricity generation will probably at least double over the next ten years, roughly equivalent to adding the present electricity consumption of the US, with savings only allowing for more people to benefit from it.

From what I have been gleaning here and there, the buildup of technical skills education has been rather good in China, so you got to have some hope that things will start to improve. Looking at electricity generation;

- the share of coal did peak in 07 at 81 percent, and while generation from coal is still increasing it was down by 2.5 points in 09 with hope for 4 by this year barring major drought.

- with hydro at 15 to 17 percent, installations going strong, and unused resource left, there is substantial room in the near future for their wind and PV capacity, and even though there remains substantial unconnected build, they seem to be more or less in the process of getting the grid up to the task.

- a few years ahead, China will be able to do a lot of solar thermal electricity in the Gobi.

- geothermal capacity is more of a long shot.

Some nuclear fission will end popping up, probably not so much natural gas and it will be coal for the rest. The latter I guess could account for about half of added generation.

The interesting one to watch for what the stamina of the local brand of policy makers can accomplish will be housing, both for existing and future stock, and passive housing standards in particular. News on achievements of past attempts at construction norms that have reached me have been mixed at best. On the other hand, the bulk of the world's installed solar collectors can be found in China and there's some geothermal heating.

Biomass equivalent of 200 megatons of oil per year (4 to 5 mb/d upstream) is already in the energy loop, much of it non-commercial, which seems to slowly come into the more efficient commercial cycle. As has already been noted by others, this part is not trivial policywise either.

Even under that scenario, global carbon dioxide emissions will increase by another 20 percent this decade before we'll be able to see any land. Quite a bit in that respect will also depend on renewables progress in the US over the decade.

One VERY positive wrinkle in this is that China is building one large, very efficient (44%) coal fired plant per month, often replacing 27% to 31% efficient generation.

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/11/world/asia/11coal.html

Same electricity, less coal, less transport, slower depletion, LESS CO2 !! :-)

Alan

Raising efficiency percentage to 44 from the default 38 I had been using for some 2500 TWH incremental Chinese build would shave off 3 to 4 points from the anticipated 27 to 28 point world carbon dioxide increase from electricity generation, 4 to 5 if anticipated incremental builds for the rest of the world are included under this hypothesis.

I also had been assuming the world default for the mix between lignite and hard coal. After checking, I found that China uses comparatively less lignite, which yields close to another point.

Assuming an additional 1500 TWH replacement over 10 years worldwide means roughly one more point increase off for every three efficiency percentage points gained thereupon on average.

Another precision I should have included in the previous post is that the 20 percentage points mentioned there are from energy use only.

Please contact me at

Alan_Drake at Juno dott conn (transform to common form, this is to avoid bots)

I have some marginal input into UN's Green Economy Initiative, and have pushed including more efficient FF generation as part of the solution.

Best Hopes,

Alan

As far fetched as this may sound, I'm wondering if China will at some point own parts of the US. I don't mean businesses or golf courses, I mean States.

Think about where things are headed. China is going gangbusters while the US is going bust. As China builds infrastructure ours delapidates. As they pave new roads ours are being turned back into dirt roads. As we borrow more and more from China, we obligate ourselves to making those payments. Well, what if our debt reaches a point where we are unable to make those payments? Wouldn't China then want US real estate in exchange for satisfying our debts with them? They will surely want something, right? What else is there that we could offer them in repayment? The only thing we'll have they'll want is more room for their people to expand. The big debate will then be which States? Afterall, not all States are created equal.

This is kind of subtle, so I'll go through it slowly.

1) China is worried about the amount of US government debt it has accumulated.

2) American oil companies own lots of Canadian oil sands assets they have accumulated.

3) Chinese state companies buy out American oil companies' Canadian oil sands assets with US government debt instruments.

4) American oil companies now left holding US government debt, and Chinese companies are holding Canadian oil sands assets.

So, to simplify, if the US government defaults on its debts, US oil companies are out the money, and Chinese companies are holding Canadian oil sands assets.

Or to really simplify, Americans are walking and Chinese are driving.

Clever, isn't it?

Are we Canadians the last ones to realize we should nationalize control?

Fire sale on resources!!!

aaargh

The Canadian government tried that when it created Petro-Canada. They lost a very large fortune on Petro-Canada before they sold it back into the private sector, so I don't think they'll ever do that again.

For some reason they assumed that owning an oil company would always make money. It will only make money if you are smart and know what you are doing, and government bureaucrats are seldom smart or know what they are doing.

Can I just nail something?

Government bureaucrats can often be smart and usually know what they are doing. The problem is the drivers on them and the determinates of 'success' are very different from their commercial brethren. If you want to measure them via the same metrics (eg profit) then you need to give the same flexibility of drivers on them.

Get that right and you'll find that in the political manoeuvring stakes, they leave the commercial world standing.

Actually, many bureaucrats are individually fairly smart, but collectively they can be awfully stupid. It's in the nature of the bureaucratic animal. They do particularly badly in the oil industry, because you have to be innovative and a risk taker to find oil, and that't the antithesis of the bureaucratic mindset.

It was actually quite painful to watch them during the days of the National Energy Policy, because oil companies (both domestic and foreign, state-owned and private) had no problem ripping them off for billions of dollars. It was particularly painful because as a Canadian taxpayer I knew I was going to have to pay for it all.

They were particularly naive about who was going to rip them off. They assumed that domestic oil companies were more trustworthy than foreign ones, and foreign government-owned oil companies were more trustworthy than private ones. Silly, silly people. You can't trust anybody.

Still, it would be comforting to have our own stupid bureaucrats in control of it rather than the stupid bureaucrats from some other country.

It is clever, RMG, except that the Chinese haven't read about the negative net energy of oil sands, so instead of driving minivans, the Chinese will be back to driving glorified rickshaws and holding heavily polluted land in Canuckistan. Maybe Pigleg can drive their rickshaws. American military will be making border raids on the Canucks on foot, since they're out of gas. At least the Chinese can have the satisfaction of winning the Chinese-American war without ever firing a shot.

What fraction of the Chinese middle-class who will be rich enough to own a car has nothing to do with renminbi, and everything to do with population size and available energy.

There's no negative energy in oil sands, the EROEI is around 6:1, and the Chinese know that.

What they don't like is the price, they're having to compete with everyone else because international companies are bidding up the prices. The French just bought another $1 billion piece of the action yesterday, and rumors are there's another big buyout deal looming.

However, the Chinese are masters of cost control, so they'll be doing their best to keep costs down.

So China's current growth rate in demand is about 7%, for the past few years

If they go the "slow" route of s Korea and grow by 600% over 20 years, that means their growth rate will increase to about 10%

the OPEC countries are also growing consumption by about 7%

when push comes to shove, OPEC gets first dibs

then anyone with dollars (oil is priced in dollars, as we know)

so china has a lot of dollars

the US has even more dollars, in fact an infinite ammount

how long do you think oil will continue to be priced in dollars?

the best line I heard (from Goldman, natch)

"buy what China buys"

"sell what China sells"

China is buying a lot of oil, and gold, and commodities

China is selling a lot of consumer goods

Hmmm...

I just saw a headline somewhere about a collapse in China`s real estate market wreaking havoc on their banks. It could happen soon, maybe this year.

After that kind of event I don`t think they will be as strong. There are persistent whispers about a Chinese "bubble" set to burst, by the way. Their stock mkt is down a lot recently.

Somehow I see whatever assets they own being sold off at low prices to other bankrupt/debt ridden/poor entities. The deflationary spiral will persist; there will be no "ooomph" from the Chinese (already there isn`t!) to keep the balls hovering in the air while gravity persistently pulls them down.

The Japanese bubble burst; the US bubble burst; the Chinese bubble is bursting....there is no escape, there is no way out, there is no way to keep driving while the others are slowly giving up their cars....

Everybody will be walking!!

The accumulation of US reserves by China is in large part because China needs to keep its currency relatively cheap to the USD. If China were to significantly unwind it’s stash of US treasuries, for example to buy US assets their currency would appreciate which would be pretty bad for their export sector - where profit margins are already slim.

A sidenote is of course that more than half of China’s exports go to Europe. My guess is that this may very well be behind their recent announcement to tie their currency to a basket rather than just the USD. The recent move in the Euro cannot have been easy for Chinese exports the Europe.

Rgds

WeekendPeak

You are basically right but I'd say the timeframe is more like 30 to 50 years.

The big four emerging and converging trends are:

1) The decline of oil

2) The rise of China as the world's foremost power

3) The decline of the dollar and American empire with possible breakup of the union

4) The rise of gold as a hard currency

All of these are baked into the cake, IMO.

US annual miles driven is about 4.58 trillion. Scaling that by the ratio of China's population to the US population, we get 19.8 trillion miles / year. That equates to 43.1 million barrels of gasoline per year at 30 mpg.

I'd expect that some combination of reduced number of vehicles per household, reduced miles per vehicle-year, better mpg, and non-gasoline/non-diesel vehicle technology will keep Chinese demand below about 20 million barrels per day. After all, the US' fleet size of 240 million vehicles would scale to 1037 million vehicles, which will take 20 years to build at 52 million vehicles per year.

The use of the Japanese and South Korean curves for those time periods is a little strange. If you examine the Japanese consumption between 1973 to 1985, it is also flat like the South Korean curve for that period, due to the '70s oil shocks and high oil prices.

South Korea grew at an average 19.92% 1965-1971, too, before chilling out for a few years. In 1967 their YOY consumption increased by about the largest in about any nation BP tracks, 42.27%, so it's odd to use them as an exemplar of semi-steadiness.

I'll also throw in that Staniford had a post on his blog both about Steven's article and a repost to it: China as Japan/Korea? 5 days ago

I think China's real GDP will decline over the next eighteen months to two years due to the bursting of its real-estate bubble. Hence I also expect China's imports of oil to decline over the next two years.

Time will tell.

After falling one year, in 1930, it appears that global crude oil demand rose throughout the Thirties, and there were reportedly three million more cars on US roads in 1937, versus 1929. After bottoming out in the summer of 1931, US crude oil prices rose at about 11%/year from the summer of 1931 to the summer of 1937.

Big difference today versus the Thirties is that instead of millions of people wanting to drive cars for the first time in the Thirties, hundreds of millions of people worldwide want to drive a car for the first time today.

Update on the $2,500 Tata Nano:

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1702264,00.html

The Chinese economy is capitalist. Capitalist economies are subject to business cycles. The faster and longer the boom, the bigger and more spectacular the bust. Let us return to this topic in mid 2012, and see exactly what will have happened to China's oil imports over the next two years. The Chinese bust could be as bad as the U.S. faced during the Great Depression--or it could be considerably worse.

Tell me about the boom and bust cycle of Taiwan, then. China is playing catch up and it is the capitalism that enables that. Business cycles are irrelevant in the longer term.

That article is from January, 2008.

Inertia. Ordinary Chinese are fantastic savers, and millions may have been saving for years for cars instead of expecting to get a loan. So while the US real estate crash wiped out credit, the Chinese get to dig into their savings, either to go ahead and buy the car due to incentive programs or to divert to regular consumption. Negative savings = stimulus. But it does mean single digit growth instead of double.

The other consideration: what will China do to the value of the yuan? The import-export effects of a strong yuan on oil consumption depend on whether the government would let people import, say, Tata Nanos to go along with all the extra oil they could now afford. Conversely, it means Chinese goods cost more overseas.

Some interesting graphs here: Technology Adoption in Hard Times. Car sales appear to have sank in the GD of course, rising again around the middle of the decade, but they never achieved the 1929 level of market saturation until the 50s, judging from a quick eyeball.

I see strong signs of both policies I advocate and those I abhor in China.

On the good side is 20,000 km of rail lines being electrified, 20,000 km of new track and numerous steps to speed up and increase capacity for railroads. Shanghai will soon go from no subways to #1 in the world by every metric (passenger, pax-km, km of tracks, # of stations, # of vehicles) while Beijing will be #2 in the world by several metrics. However, Urban Rail is apparently restricted to the ten largest cities.

A good source of subway maps, but not the future Shanghai one with 16 (17 ?) lines.

http://www.chinatouristmaps.com/china-maps/subway.html#shanghai

OTOH, bicycles are being phased out and car sales are #1 in the world.

The grid appears to have "caught up" and diesel generators are idle. This could change.

So there are strong trends in both directions.

Best Hopes ?

Alan

Not so fast: http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1904334,00.html

Electric bikes are a fairly new technology that has "clicked" recently; in 2009 the number of new E-bikes sold in China was almost equal to the total number of existing registered cars. All indications are that its a transportation solution rising rapidly (where there is infrastructure to allow it), and its much friendlier to those of small means than the old american-style steel and glass cages.

"car sales are #1 in the world"---I believe that is a trend to be applauded. I don`t like cars, of course, as anyone who has read my posts knows. BUT without the Chinese taking over, thermodynamically speaking, from the Americans, to transition to benefitting from energy flows which have a lower EROEI, we wouldn`t have the knowledge, surely, that we are scraping the bottom of the barrel. I man, we have to get this process over, of converting all this oil to CO2, before we can transition to the next thing, maybe it will be renewables since that`s all that is left.

The Chinese have a lot of cars that are much lighter than US cars. So they are not "pushing as much car" around per driver. They are happy to get lower EROEI oil because they compare it to bicycles and wheelbarrows (well, that is starting to change and that is why their economy will be in trouble too soon).

The Vietnamese are now the next economy ripe for exploitation.....but that boom will be even shorter than China`s, their car purchases even lower, their cars even lighter....

The Chinese by buying lots of cars are helping to take down the world oil consumption more gradually over time. I believe many governments seek to make this process as gradual and easy-to-adjust to as possible, the slope if it is too steep is too unmanageable. But still if China were populated by a bunch of environmentalists who said "no cars!" then in the long run, of coure, the green fields, clean rivers, trees, forests, and mountains are going to be the most valuable, necessary things anyone could imagine. Because those things capture solar flows so well.......

I generally don't find much insight in this kind of top-down projection based on per-capita consumption. China's population of 1.3 billion means any per-capita projection is going to result in numbers that are exceedingly large, but it says very little about the drivers of usage and how they might differ from country to country.

Our preferred method is bottoms-up accounting, looking at each technology (e.g. refrigerators, cars, electric arc furnaces, etc), their energy intensity, energy efficiency, and fuel mix, with an understanding of their usage patterns/activity levels, substitution potential, and efficiency trends. With this, you can add up all the resultant energy consumption and let that provide a projection.

This articles appears to conflate "gasoline" for cars with "oil". Currently, gasoline consumption in private cars in China accounts for only 7% of total oil usage, compared to 40% in the US. It is far exceeded in use in the transportation sector by diesel, which powers trucks, boats (China has among the most extensive coastal and inland waterway transport network in the world), trains (though China's rail system is now 40% electrified and their diesel-based system is almost as efficient as Japan--in energy terms, not logistics) and buses (for the 700 million urban residents). Yes, car ownership is growing rapidly (from a very low base, so percentage changes are high), but China's vehicle efficiency requirements (on a per-vehicle basis, without the kinds of CAFE loopholes the US has) means the average new car gets over 30 mpg, with further tightening of the standard to come. (The typical Beijing car is not a typical China car--there is a lot of China outside of Beijing). Based on surveys, the average private car is driven about 10,000 km per year.

We also use a diffusion model to look at future vehicle ownership (based on income on the private car side, for example, and demand for freight transport for trucks). With this approach, we see a vehicle fleet of over 300 million by 2030, more than the US today, but of which about 160 million are private cars.

Other major uses of oil include petrochemicals (about 25 million tonnes of naphtha), construction (all those cranes in cities, road-building, and rail-building needs diesel), coal mining (diesel based), agriculture (most irrigation is diesel based, as are the tractors), and direct industrial use, but virtually no oil is used in power generation, aside from times of shortage and drought when small diesel generators proliferate.

When you look at all these activities, the technologies in use, and their energy intensities, by 2030, our forecast for total oil demand is a bit over 800 million tonnes, or about 16 million b/d, not much different than what EIA is projecting (though I know from working with EIA that their results are derived in a very different manner.) Of this, gasoline demand for private cars remains far below the US proportion, at about 26%. In other words, the demand for cars is an important driver for understanding China's oil demand, but it is not the key driver--industrial activity and resultant demand for transport of goods is far more important. (China produces now 3 billion tonnes of coal, of which about 60% moves by rail, accounting for half of national rail capacity. The growth in coal demand--driven by electricity demand, which in turn is driven by industrial power demand--has increasingly displaced freight from the rail system to the road system, including hundreds of millions of tonnes of coal. Though rail expansion is being accelerated (China consumed 200 million tonnes of cement in rail expansion in 2009--they use concrete ties, not wood--more than twice total US consumption of cement in all forms), it cannot offset the even higher growth of demand for moving goods.

Of course, I don't expect this China (nor the Chinas alternatively projected here) to come to pass. In our model, in 2030, China is producing only 2 million of the 16 million it would be demanding under this scenario, resulting in an import demand of 14 million b/d. While that might be 25 to 30% of world crude oil production in that year, it almost certainly would account for or exceed world traded crude oil in that year. And despite its trillions, it can't buy what doesn't exist.

Very interesting, but I think a bottom up approach may miss some consumption. Do you test your methodology with historical data from other countries?

As an intermediate level of analysis between bottom up and top down I think separating Chinese demand into income levels and finding analogs that are representative would be useful. Use present day Vietnam demand to represent the low income tranche, Thailand for middle income and South Korea for high income and simply provide estimates for what proportion of China's population will fit into each of these catagories in the future.

Reading this string so far I keep wondering just that. What fraction of the Chinese population is ever going to become rich enough to own a car?

It seems inconceivable, given China's already dense population that they can continue to provide the training,jobs and infrastructure needed to enable that much motoring.

I don't know if there are any plans to sell the $2,500 Nano in China (see update up the thread), but a lot of consumers in China could afford this car.

In any case, I wonder what fraction of the US population in 2020 will still be rich enough to own a car?

That question would seem to imply a very steep downslope since car ownership is fairly high in some countries with a third or a half of the income in the US. You have to go fairly far down into the dumps before it drops an order of magnitude.

So maybe we'd see some fractionation or sorting. There would be those rich enough to keep an existing car going somehow - which on the example of Cuba might be a surprisingly long time. There would be those richer enough to replace said car when it finally died. And there would be those out in the country who would be subsidized at any cost to drive at least enough to make farm life livable, assuming that the city folks wanted to continue eating.

Oh, and while it would incur shrill moralizing from starry-eyed idealists, we could always change the rules - many of which are as much about protecting incredibly cushy union jobs as they are about "safety" - and make something like a Tata Nano legal.

General Motors is already selling more cars in China than they are in the US, which shows where things have been going recently. I think the future has arrived a lot faster than most people were expecting.

"In any case, I wonder what fraction of the US population in 2020 will still be rich enough to own a car?"

Or asked another way, given the inefficiencies and distances involved, I wonder what fraction who does own a car will be able to afford to operate it.

A vehicle's value could double depending on whether the tank was full or not.

I did some calculations to figure that out, and you know what the answer is going to be? Most of them.

This is scary because there are four times as many Chinese as Americans. No, really, the majority of Chinese will end up owning a car. It will be a much more fuel efficient car than most Americans buy, and they will drive it a lot less, but they will buy a car.

This is okay for the nouveau rich Chinese, but Americans might want to consider the implications of it for themselves. They aren't going to be buying nearly as much fuel as they used to because the Chinese will be buying it instead.

Sparaxis - who is this "we" you refer to? Some agency you work for?

Gasoline consumption in 2006 was 17.95% of the total according to EIA, not 7% as you state, unless there's some use for gasoline I'm missing - lawn mowers? Molotov cocktails? This level of % consumption has only marginally declined since 1994.

Not an agency...a national lab. The number I cited was for private cars only--that is, those vehicles subject to discretionary usage. I segregate those from fleet cars (paid for by the unit, and thus used in a different manner than those owned privately), and from taxis, light- and medium-duty trucks, etc. that are also not subject to discretionary usage. The point is to show that private ownership of cars is not the major driver of oil usage.

Keep in mind that China records product usage in the old Soviet style--by who consumes it and not by manner of consumption. So you end up having "industrial gasoline consumption" which is gasoline consumed by vehicles owned by industrial enterprises. So you have to do an adjustment for gasoline and diesel to take this statistical quirk into account.

Yes, we have models done in this fashion for a number of countries, and all are calibrated with historical data. The main challenge of bottoms-up modeling is that it's data-intensive. You have to know, for example, how many vertical shaft kilns there are in the cement industry, for example. The diffusion model I referred to is essentially an incomes-linked approach, but I think you need to use international comparisons with some judgment. For example, we don't assume that China air passenger miles per person will approach anywhere near other large countries such as the US because of the rapid expansion of high-speed rail, which will likely cannabalize short distance air travel. But like with any modeling approach, the output is always wrong...

I like your bottom-up model -- that's the way I'd do it too.

A couple of questions, though:

1. Do you allow for demographics? China's working-age population will peak in 2015. We are entering unknown territory from the point of view of demography (this is the first time in Man's existence on the planet that the "population pyramid" will change from pyramid-shaped to block-shaped for a large fraction of the world), but it seems likely that per-capita consumption of transportation will be depressed compared to historical norms.

2. In opposition to point 1, do you allow for structural changes in China's economy? Both the EU and the US intend to grow net exports, so production for internal consumption and services are going to have to grow very quickly as proportions of Chinese GDP. Simple application of historical patterns would underestimate per-capita oil consumption.

The mean per capita income may have increased, but the median income sure hasn't in real terms. The distribution of income will affect the consumption patterns and in the US the distribution of GDP growth has been concentrated at the top since 1979. Perhaps if that hadn't been the case, our consumption would have been even higher? I can't imagine how, but I'm sure it could be done.

The GDP growth alone, or combined with the acquisition of motor vehicles, isn't enough to predict energy demands. Distribution of the wealth also must be considered.

Also, while economists may wrongly believe that energy commodities are easily substituted for each other and thus one doesn't need to worry about the supply of any one, it is also incorrect to ignore any kind of substitution and factor in the entire energy consumption picture.

Overall I think China's growth will create more oil demand than predicted by the EIA, but the story is more complicated than depicted here.

It doesn't surprise me that the IEA's figures are goofy.

The situation with PO makes me feel like we're back in the couple days before hurricane Katrina made landfall in New Orleans. The data clearly says the storm is more than the levees can handle. TPTB are freely acknowledging that there is a problem when you pointedly corner them & ask them about it, but they show no emotion or signs of action whatsoever.

When the hurricane finally did hit New Orleans, those same TPTB all suddenly acted surprised and started running around like chickens with their heads cut off. They intellectually understood that the levees would break ahead of time, but it was clear that they had just remained in complete emotional denial about the oncoming problem until it hit them in the face.

Sad but true, in a democracy, policy is done through crisis management. In order to mobilize a majority of public opinion, a crisis needs to be precipitated. Take WWII as an example. POTUS Roosevelt knew for many years that the US would enter WWII, but he was powerless to act and had to wait for events to force the population into action.

The same is true for the upcoming peak oil crisis. Attempts at preemptive action to mitigate the effects of diminished supplies of oil will not be successful. A crisis situation will eventually mobilize the populist to action.

The government should support all possible alternative technologies to oil use so that the crisis when it eventually arrives will be mitigated and so that the public desire will be immediately satisfied.

Brilliant observation and correlation. And like you say what will be different about what happens as a result of peak oil? Nothing. People will run around like chickens with their heads cut off looking for someone to blame claiming no one saw it coming. Yet, here we are discussing this topic on TOD for years in advance of its occurance, with only a small percentage of the population truly comprehending intellectually how bad things will probably get. It's called waiting for the other shoe to fall, and what a sound it will make. Oh my!

Thanks for the compliment.

I don't know whether PO will ever give the kind of abrupt spike of catastrophe that Katrina did, or whether we are just in for a more drawn-out economic donwturn through the world. (Maybe that's the question of the decade around here?)

If if spikes us at some point then I'm sure we will see a similar psychological response that we did to Katrina. Everybody's pissed that nobody saw it coming, except that everybody did see it coming. A person can be informed about the dangers of something and still not "know it" at the gut level at all. (See: being a teenager)

If PO never gives us any sharp sudden spike of catastrohe (and my guess is that it won't) then I think we're looking at what amounts to the same human response anyway. It's just much more drawn out. We're decades into it already.

Right now it's 2010, Saudi Arabia's production capacity has hit the wall, worldwide oil production has plateaued & may be falling, an economic crisis suddenly hits us at this exact time . . . and out culture is still sitting around referring to the "possibility" of PO as if the problem's existence is actually in question. Ahh, the sweet smell of denial.

Something is nagging at the back of my mind about this article. I will try to put it into understandable terms (if only to help my own understanding).

I think that an implicit assumption throughout The Oil Drum is that levels of economic activity and energy use are one and the same thing. If economic activity increases, then energy use will increase in a commensurate fashion. This proposition is usually put in the form that suggests that if energy use decreases (for example due to reaching peak oil production) then economic activity will also decrease.

The comment was made several times in this article that per capita oil use in most developed economies has decreased over the last several years, but in spite of this decrease in oil use, levels of economic activity increased significantly over the same period of time.

I agree that the Chinese see problems with matching their energy use with available supply, but they don't seem to be panicking. Directed action seems to be their preferred operational mode.

I'm with you, Poobserv, that economic activity, whether it's useful or not, maximizes energy throughputs. It also generates heat; here's a better correlation of world population and CO2 emissions. World population also correlates pretty closely with oil production (couldn't find a convenient graph). The author here is suggesting that oil/GDP correlation is a useful tool for predicting causation, when the use of GDP simply measures how much heat is being blown off into the atmosphere in useless churning of the economy as we send our fake dollars to China in return for their fake plastic toys. What good are these national oil demand curves when looked at in isolation from global supply? So, yes, Poobserv. Energy drives the economic activity, not the other way around. Energy drives the money, not the other way around. Economists have a lot to answer for in how we've learned to think backwards about everything. Build it and they will come?

http://amatterofscale.chaoticreality.net/chapter11.htm

The per capita oil demand in the US has been falling since 1980 because we've had to "steal our opponents' game pieces" since then, and that game gets harder and harder to sustain in terms of international trade imbalances, as we are currently finding out (maximum power principle again). http://www.theoildrum.com/node/6681#comment-668660

I think you might have misinterpreted my comment which was more a question than an assertion. This post seems to broach the possibility that economic growth can happen without increased energy use.

What got me thinking about this possibility is the assertion in the article that oil use has peaked in the large developed economies, but economic growth has not stopped.

The implicit model that seems to be put forward in this article is that there is an S curve for oil demand. The implication of an S curve model is that there is a period of fast growth followed by a leveling out of demand. This model is far less pessimistic than the one that seems to underly The Oil Drum because if you can get through the increase in demand phase then there is a possibility that things might improve as demand slows down.

Thanks for interpreting for me, Poob. You're right, my heart wasn't into interpeting this one; the OP was hard to understand because of the economese he uses. But that was my understanding, that here's an author who thinks we can control and measure a nation's energy through monetary manipulation. I'm just saying that because he explains and measures with tools such as GDP that basically measure churn (entropy), its hard to even have a discussion.

The oil/GDP thing IMHO makes only sense if viewed globally. The fact that per capita energy consumption has slowed in the US has to be viewed in the context of increasing imports of goods and services.

As I’ve pointed out in a previous post the correlation between the quantity of oil consumed and global GDP is in the 98+% range.

What does happen is that depending on the stage of development of a society FF use is directed differently – if you’re using FF to run a factory that makes widgets it will impact GDP differently from if you use that same FF in an SUV to go window shopping at the mall. One is intermediate consumption – i.e. something tangible is produced using the FF whereas in the second case it is final consumption and nothing tangible (in GDP terms at least) is produced.

FF/ GDP is a multi dimensional puzzle which changes with societal development, preferences, geography, EROEI etc etc.

Rgds

WeekendPeak

Does GDP measure externalised costs for improved GDP efficiency? For example, fighting wars in countries with large amounts of oil.

Anyway, I expect to see GDP efficiency increase in 'service economies'. Energy is a measure of activity, service economies by their nature are not the same as manufacturing economies. Just speculating, not really sure of the answers.

I would question how useful the comparisons with Japan and South Korea are. In both cases, petroleum consumption rose dramatically as ownership and use of private cars rapidly expanded during a period of low oil prices. In the case of Japan, this was during the 1960s. South Korea had to wait until prices dropped in the 1980s. I don't think that we can expect to see prices so low, relative to incomes, ever again. High relative prices will most likely deter all but the more affluent Chinese households from adopting a private-car lifestyle, unlike the examples from Japan and South Korea. Considering that rural Chinese households tend to have relatively low incomes, they are especially unlikely to be able to purchase and maintain a vehicle. Village cooperatives might share the cost of a truck to bring goods to market, but individual families will probably continue to travel by bicycle and bus. In cities, incomes are higher, but the need for private cars is less because of shorter distances and an infrastructure of public (mostly bus) transit. Households that can afford to purchase cars are likely to do so as a matter of prestige, but those cars are likely to stay parked much of the time for all but the more affluent households that can afford gas prices. Therefore, the slope of a graph showing petroleum consumption is likely to be less steep for China than for Japan or South Korea.

Those points sound valid.

But a moderate increase in the Chinese demand for oil is sorta like having just a small amount of the world's total deepwater oil reserves flowing openly in the Gulf. The problem is still pretty catastrophic for us in real terms.

Differences were, during the Korean and Japanese expansions oil was plentyful and cheap (and largely believed to continue that way for the forseable future). Now at least at the elite level within China, those assumptions are inconceivable. And we/they have some options that didn't exist back then such as electric vehicles. So whether it be because of price, or recognition of current and future scarcity, China won't just blindy increase it's oil demand like that, there will be serious attempts to limit it.

About the only thing we can do at this point is try to wean ourselves off of oil...I've been weaning my family off for over three years now and made some videos to help people do the same...I attached one here...

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hHmXhgBhtWk

MrEnergyCzar

The Australian economy has escaped recession largely because China keeps buying boatloads of rocks... coal, iron ore and so on. If China slows it will take Australia with it. Lack of future oil is not the only problem. China uses some 12X as much coal as Australia exports. When China's domestic coal production peaks perhaps by 2015 Australia simply won't be able to supply enough. Right now export thermal coal prices are around the $100/t mark. To hell with global warming, there's money to be made.

Before any major slowdown in the Asia-Pacific region I think there will be mixed messages. At first everything will seem great in Australia with high export prices for coal and LNG. Later the global energy shortage will bite and most economies will contract. I expect the 'bottom billion' in China and India will see their middle class aspirations fade away.

My theory is that the lack of oil is not the problem. I believe oil created the problem for which the lack of oil will ruin us. Before we used fossil fuel, we lived without it. But now, all our homes, and shopping centers and modes of transportation depend on it. We can drive to the suburbs, meaning we can have bigger houses in order to store more things, even while the jobs to create those things are being shipped to China or automated. But no one really needs all that stuff. We need food and clothing and shelter and water, in the smallest doses tolerable.

But our appetites and our infrastructure were designed to use as much oil as possible. As soon as that ability to use oil is gone, the infrastructure and financial system will have very little value. Then where will we be?

Forgive me if I am not oil-centric, but everything depends on everything else. It is going to be like learning to ride a bike without training wheels, but much more difficult. The whole of the economy, government and infrastructure will have to be rebuilt around other possibilities that we do not even know about yet. If we cannot do that, we will tip over, and so will China.

That might be why China is beating us in the race to build wind turbines. And it is advisable that no oil or automobile industry types will be ripping up any tracks there and covering them in asphalt any time soon.

It may be true that per capita oil consumption in the U.S. has declined but it is also true that there are many more "capitas" all the time. U.S. oil production peaked in 1970, when the population of the U.S. was about 203 million. Today it is nearly 310 million and is increasing at the rate of one person every 11 seconds.

China's economic future is going to be confounded down the road by a rapid aging of its population. One effect of its much lower birth rates, mainly as a result of its one-child policy, is that the distribution of its population is moved upward in its age pyramid.

In the meantime it seems to me that, barring some catastrophe far worse than BP's gulf fiasco, China, the other BRIC countries, and a host of other nations, including the U.S. will continue to find, extract, and burn oil, a game that will come to an end, but not as soon as some might think. Aside from the Middle East, where we spend billions every year and have numerous military bases in an effort to discourage others from getting better access to oil there, look at other places where oil is known to exist in at least relative abundance. For example, look at a map of oil and gas pipelines going in all directions away from the Caspian Sea oil and gas fields. Look at Nigeria, where everyone is trying to muscle in on the oil fields in the Niger Delta and offshore. Look at the fights that are already developing, at least on paper, for access to the now-frozen Arctic, waiting for better access as annual ice melts grow larger.

More people (currently about 80 million annually), along with future economic growth (currently depressed in many places), can only add up to future struggles to increase access to energy supplies, especially oil.

glp:

All China has to do is avoid a boondoggle like Medicare and they won't have the problem that the socialist West does. The irony...but it's true!

If China, and to a lesser extent Japan and Russia, get this right and let their old pass away with dignity and keep birth rates low they will become the richest nations on the planet. Historically it's always been the case that when death rates exceed birth rates, populations decline, the value of labor increases, and the remaining survivors are considerably wealthier per capita.

Of course migration has to be factored in. It seems in the U.S., as part of our collective psychosis, we are committed to open borders and unlimited medical support for the aged. We will soon be bankrupt and third world because of it.

Old people don't want to die with dignity, they don't want to die at all.

I'm one and I know.

China will implement universal health care before the USA does.

http://www.china.org.cn/government/central_government/2009-04/06/content...

Alan

As the article states, the Chinese plan to have 90% of their population covered by basic medical insurance by 2011.

The fundamental difference from the American system will probably be that it will be much, much cheaper. The Chinese are very good at cutting costs.

Read the following: http://dailyreckoning.com/emerging-market-investing-why-your-portfolio-s...

It is possible to have universal health care that is cheap and affordable.

Well a universal system is probably much better than Medicare, which pits working people, who may never live to see the benefits (or who may find that the benefits are no longer there once they reach 65) against the elderly.

In any event my basic points remains the same: the humane, reasonable thing to do in a post-peak environment is to have death rates exceed birth rates so populations naturally decline to allow future generations to have some shot at a decent existence.

The best way to do this is some form of birth control policy (one child vs. tax breaks for childless couples etc., anything is better than nothing) and avoiding excessive state medical expenditures on the elderly.

Or, of course, we could rely on the Four Horsemen.

Only when we are all unemployed because we can no longer kill for, or depend on oil, will we see the truth. Right now, anyone who has a stake in our current economy configuration wants the public to fly blind.

Cars vs whatever:

There are several practical issues sometimes skipped, notably

How flat is the local ground? How often is snow -- ice storms are equally disabling for all -- an issue? What works in Florida will do poorly in Los Angeles hills or in Syracuse, N.Y.