Why Malthus Got His Forecast Wrong

Posted by Gail the Actuary on January 11, 2013 - 5:38am

Most of us have heard that Thomas Malthus made a forecast in 1798 that the world would run short of food. He expected that this would happen because in a world with limited agricultural land, food supply would fail to rise as rapidly as population. In fact, at the time of his writing, he believed that population was already in danger of outstripping food supply. As a result, he expected that a great famine would ensue.

Most of us don’t understand why he was wrong. A common misbelief is that the reason he was wrong is that he failed to anticipate improved technology. My analysis suggests that there were really two underlying factors which enabled the development and widespread use of technology. These were (1) the beginning of fossil fuel use, which ramped up immediately after his writing, and (2) a ramp up in non-governmental debt after World War II, which enabled the rapid uptake of new technology such the sale of cars and trucks. Without fossil fuels, availability of materials such as metal and glass (needed for most types of technology) would have been severely restricted. Without increased debt, common people would not have been able to afford the new types of high-tech products that businesses were able to produce.

This issue of why Malthus’s forecast was wrong is relevant today, as we grapple with the issues of world hunger and of oil consumption that is not growing as rapidly as consumers would like–certainly it is not keeping oil prices down at historic levels.

What Malthus Didn’t Anticipate

Malthus was writing immediately before fossil fuel use started to ramp up.

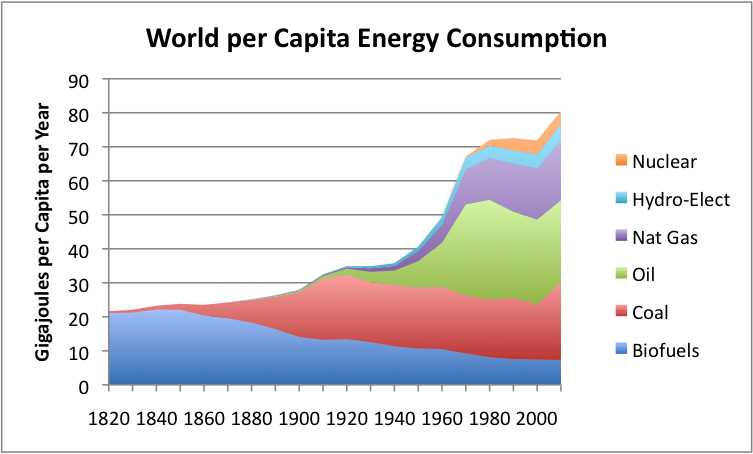

The availability of coal allowed more and better metal products (such as metal plows, barbed wire fences, and trains for long distance transport). These and other inventions allowed the number of farmers to decrease at the same time the amount of food produced (per farmer and in total) rose. On a per capita basis, energy consumption rose (Figure 2) allowing farmers and others more efficient ways of growing crops and manufacturing goods.

If it hadn’t been for the fossil fuel ramp up, starting first with coal, Malthus might in fact have been right. As it was, population was able to ramp up quickly after the addition of fossil fuels.

A person can see that there was a particularly steep rise in population, right after World War II, in the 1950s and 1960s (Figure 3). This is when oil consumption mushroomed (Figure 2, above), and when oil enabled better transport of crops to market, use of tractors and other farm equipment, and medical advances such as antibiotics. The Green Revolution allowed agricultural production to expand greatly during this period. It used fossil fuels (particularly oil and natural gas) to enable the synthetic fertilizers, irrigation, hybrid seed, herbicides and pesticides, allowing increased food production.

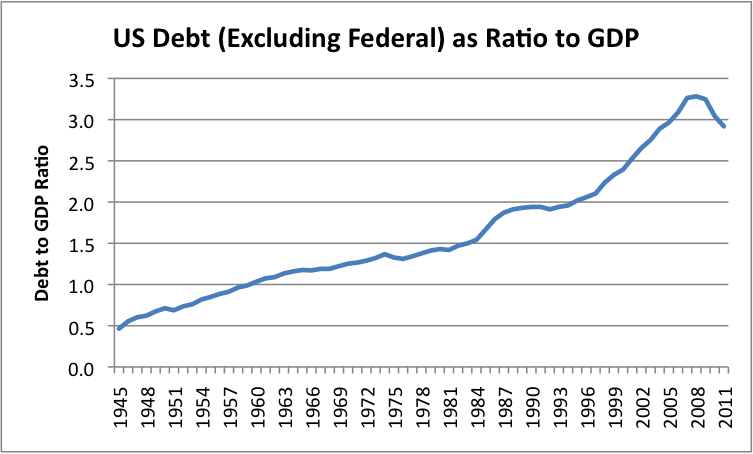

It is likely that increased consumer and business debt following World War II (Figure 4) also played a role in the post-World War II ramp up.

The reason I say that debt likely played a role in this ramp is because at the end of World War II, people were, on average, pretty poor. The United States had recently been through the Depression. Many were soldiers coming back from war, without jobs. Without a ramp up in factory work and related employment, many would be unemployed. A ramp up in debt fixed several problems at once:

- Allowed low-paid workers funds to buy new products, such as cars, that used oil

- Allowed entrepreneurs funds to set up factories

- Allowed pipelines to be built, and other support for ramped up oil extraction

- Provided jobs for many coming home from the war effort

The debt ramp up, and the resulting increase in oil production, raised living standards. Figure 2 shows that the increase in per capita energy consumption was far greater in the 1950 to 1970 period when oil production was ramped up than in the coal ramp-up between 1840 and 1920. The long coal ramp-up period does not appear to have been accompanied by such a big ramp-up in non-governmental debt.

Tentative Conclusion

A tentative conclusion might be that as long as we can keep ramping up availability of energy products and debt, Malthus’s views are not very relevant.

Of course, things aren’t looking as benign today. World oil production has been close to flat since about 2005 (Figure 5).

The world has been able to increase production of other fuels to compensate so far. Unfortunately, the big increase is in coal (Figures 1 and 2). This mostly relates to growth in the economies of Asian countries, which are large users of coal.

The cost of oil has more than tripled in the last ten years. The higher cost of oil is a problem, because it leads to recession, unemployment, and governmental debt problems in oil-importing countries. See my posts High-Priced Fuel Syndrome, Understanding Our Oil-Related Fiscal Cliff, and The Close Tie Between Energy Consumption, Employment, and Recession.

Continued increase in debt now seems to be running into limits. Federal government debt is in the news every day, and non-government debt seems to be contracting relative to GDP, based on Figure 4.

Looking Ahead

I am not sure that we can conclude that we are headed for catastrophe the day after tomorrow, but the graphs give a person reason to pause to think about the situation.

The reason I write posts is to try to pull together the big picture. If we only look at the latest new item forecasting huge increases in tight oil production or talking about 200 years of natural gas, it is easy to reach the conclusion that all of our problems are past. If we look at the big picture, they clearly are not.

Debt problems are closely related to high oil prices in recent years. Debt problems are today’s issue, and they are not being considered in the huge oil and gas forecasts we see everywhere. The new tight oil and the new shale gas resources likely will need to be financed by increasing amounts of debt, so there is a direct connection with debt. There is also an indirect connection, through governmental debt problems, higher taxes, and the likely resulting recession (leading to lower oil prices, perhaps too low to sustain the high cost of extraction).

Also, it is interesting that the supposedly huge increases in US oil supply don’t really translate to any discernible bump in world oil supply in Figure 5.

We know that the world is finite, and that in some way, at some point in the future, easily extractable supplies of many types of resources will run short. We also know that pollution (at least the way humans define pollution) can be expected to become an increasing problem, as an increasing number of humans inhabit the earth, and as we pull increasingly “dilute” resources from the ground.

Based on earth’s long-term history, and on the experience of other finite systems, it is clear that at some point, perhaps hundreds or thousands of years from now, the earth will cycle to a new state–a new climate with different dominant species. It may turn out that these new species are plants, rather than animals. The new dominant species will likely ones that can benefit from our waste. Humans would of course like to push this possibility back as long as we can.

At this point, my goal is to pull together a view of the big picture, in a way that other analysts usually miss. The picture may not be pretty, but we at least need to understand what the issues are. Is the shift in the cycle very close at hand? If so, what should our response be?

This article originally appeared on Our Finite World here.

Greetings TOD'ers ... I presume Malthus is wrong about "when" we run out of food ? ... is it not elementary to say that we must eventually exceed the capacity to feed everyone ? Will we not reach a limit to sustain the growing population ? Why was Malthus wrong is my question. curlyq3

The way the system works is more complicated than "running out food". What happens is that the financial system is affected, and this ultimately brings down the system. I write about this, based on the research work of Peter Turkin and Sergey Nevedov in Secular Cycles, in my latest Our Finite World post, 2013: Beginning of Long Term Recession.

What Malthus got wrong was the timing, because of changing world events.

It seems the human population will stop growing at 9-10 billion. There should be no major problem feeding that many sustainably using modern techniques. Of course, the human population might start growing again, since evolution should trump culture eventually. Then, at some point, we might need to limit the number of children. But that's more science fiction than anything.

We are destroying the world just trying to feed 7 billion. The long term carrying capacity of the earth, even with modern agriculture and plenty of fossil fuel is likely less than 3 billion. To ignore what is happening to the world and say, "but 80 percent of the world's population of human beings are well fed" is more than a little absurd, it is unconscionable. Any person making such a statement is implying that nothing matters except that most humans have a full stomach.

Ron P.

Of course, I don't agree at all. Agriculture and food production is not that big a problem, sustainability-wise. Also, we can and will improve by more GMO and more tech to use less land and resources for substantially more output.

Geeze, I don't think there has ever been a point further missed in the history of the internet. I said:

Any person making such a statement is implying that nothing matters except that most humans have a full stomach.

And that is exactly what you are implying.

I was referring to the destruction of rest of the world's flora and fauna while only Homo sapiens survive. And you are only concerned with the survival of Homo sapiens.

I think you will be very surprised to find out that we cannot survive if we destroy the rest of the world, as we are quite obviously doing.

Ron P.

Thought I covered that in my "sustainability"-remark.

Ron, Jeppen is a guy who believes we have a "star trek" future. http://www.theoildrum.com/node/9419/914786 Enough said.

It was not to be taken literally. I have no idea if it ever will be feasible to travel among the stars or if we'll ever make contact with aliens. But I do think we have a human golden age in front of us. And that, I think, given the progress we have had until now, is a respectable viewpoint, at least in the fairly large world that exists outside of TOD.

Respectable? By whom? The main stream media? The "guy" in the street? The ag school scientists whose paycheck depends on funding by ag giants? So I guess "reality" is determined by consensus.

The nice thing about living in a very rural community in South Central Illinois is I see how food, and I use that term lightly, is produced. The amount of chemicals, nitrogen, and minerals that are used to make land productive for agriculture are astounding. Much of the land is marginal, but is pressed into production out of greed. Most of the micronutrients have been depleted long ago. No amount of artificial genetic modification will make up for this. There is no free lunch.

Respectable by anyone who has had a look at the stats.

I kind of trust the ecological footprint numbers for lack of better sources (if anything, I'd expect them to be pessimistic). And my perception of food production in my Sweden is not the same as yours (of course, "greed" and "astounding amounts" are not very measurable). So I'll guess we have to agree to disagree.

And the very source you cherry picked your graph from provides a very doomerish report from the world wildlife fund, which includes the graph you posted (warning! very large pdf file) http://www.footprintnetwork.org/images/uploads/LPR_2012.pdf Very depressing.

Greed is very measurable. It is measurable in the acres taken out of fallow to capitalize on high commodity prices. In the acres of forest are cut down to make more fields for agriculture. In the tons of fish mined from the seas. In the species that are killed to provide "parts" desired for mythical qualities. Of course, some of the Ayn Rand mindset might call this virtue. Interesting that the above report states agriculture is responsible for 20% of carbon emissions.

Cherry-picked? It's not like there are multiple alternative datasets for this, or? I searched for global footprint data and this graph displays it. That the report is doomerish a given. Again, we are deep into overshoot but sans carbon, we are not, and the trend is not bad either (sans carbon). Thus, if you're optimistic about carbon, as I am (long term), then you should be fairly optimistic about the total footprint.

And yes, I would call it virtue. Not the rare-species-killed-for-virility thing, of course, but for doing more agriculture to meet increasing demand.

Sorry, but the carbon is already baked ito the cake, and will be with us a long time. How did I know you would call it virtue? Because I used to be you.

Yes, the carbon will be with us, and we will have to live with the consequences. How bad it will be, we'll just have to see. But I think we will, eventually and by choice - not by die-off or similar, come down in carbon levels and undershoot the carrying capacity of the Earth.

What if an ordinary bloke is raised in Christianity, and then get atheist friends and decides to not be Christian anymore? Is it reasonable for him to tell the pope that "I used to be you"? Ok, you might not be ordinary, and I'm not the pope. But I do know I'm fairly sophisticated and I kinda doubt you have ever been me.

Jeppen,

First, the thought of our "Minnesotans for Global Warming" group came to mind when I saw you were posting from Sweden. :) In your country's position, it would be pretty easy to think that another few degrees upward wouldn't be a bad thing. The thing most people don't realize is that cold oceans are generally far more productive than warm oceans because of nutrient mixing due to upwelling. So even a few degrees could cause a huge loss of ocean productivity.

I would like to share your optimism, and I think there is a small chance we could pull it off, but I think a massive cultural change to a caretaker attitude will need to happen first.

And modest too!

What evidence do you have of this? I think you greatly over rate rationality.

There are many reasons:

1. Environmental regulations seems to get tighter all the time. Even ignoring AGW, gasoline, diesel, coal and biomass won't burn clean whatever you do with them, and so cause cancers and other diseases that we'd like to get rid of.

2. The world is soon democratic overall - this common ground will make it easier to agree.

3. The world is becoming ever-more prosperous - this makes sacrifices easier to bear.

4. People are becoming smarter and more scientifically inclined. This improves prospects for AGW action.

5. The heat will go up, literally. That will make it easier to agree.

6. Tech progress will make it easier to use alternatives to fossils for a wide range of applications. For instance, EVs have better performance and comfort in every way but range. The range issue will slowly improve.

7. Carbon taxes are appealing to politicians in most countries. They get some environmental cred and some revenue to play with.

1. In the US environmental regulations are at a standstill due to governmental stalemate. Read the stories about pollution in china today. If the economy doesn’t improve, look at this trend to continue.

2. Democracy doesn't always result in agreement, in fact, Jared Diamond, in the book Collapse, shows that it more often leads to inaction. A “philosopher king” is often the better arrangement. Want to apply for the job?

3. And most conservative thinkers would say that regulations would destroy that prosperity. Look at the resistance for the wealthy to share a greater burden. The trend is more like "I got mine and keep your hands off it!".

4. Sorry, but my experience in dealing with working class people every day at my employment indicate that the larger segment of the population is getting dumber, and it is this segment of the population politicians cater to. As Adlai Stevenson stated long ago in response that he was going to get the thinking person’s vote, “"That's not enough, madam, we need a majority!". More true today. Add fundamentalist religion to the mix and it really looks dire.

5. The heat goes up, and so does the denial. By the time the symptoms manifest themselves, like cancer, it is probably too late.

6. EV's are nice, unfortunately many people cannot afford one. Ever look at the average age of the auto fleet in the US lately? It’s going way up. Auto loans are impossible to get if your credit rating is destroyed. I’m driving a 15 year old vehicle.

7. Carbon taxes are being resisted by the conservatives.

The truth is humans are an irrational creature. I suggest you look at Reg Morrison’s “Spirit of the Gene” or Craig Dilworth’s “Too Smart For Our Own Good” (a professor from Sweden).

Ok - I don't follow US politics that well. But I thought natgas was only part of the reason coal has declined - I've read the Obama administration's regulation can take part of the credit. Is that untrue?

Absolutely, it would be so good! And I can relate to the inaction thing in intra-state politics (just look at nuclear power). However, in inter-state politics, I think common ground make things easier.

Well, internalization as a tool for optimization of outcome is not embraced by everybody, but perhaps by most, especially among economists. It is not that difficult to make the case. Also, I think conservatism will tend to give way to libertarianism over time.

I can't really accept that anecdote. The Flynn effect is quite universally accepted.

Perhaps, we'll see. If not, it will be part of what enables us to get off fossil in this century.

While many can. This is always the case with new tech.

OTOH, some change happen eventually, when the balance of power has shifted temporarily, and then is fairly irreversible and quickly accepted. I do recognize that the US is especially paralyzed in matters like this. But while your comment is very US-centric, the US is actually getting increasingly irrelevant in global matters. More and more progress is lead by other countries such as China.

What is your definition of 'progress' or 'golden age', or even 'we'?

The progress we have had is less wars and violence, better nutrition, lower levels of poverty, better tech, a long list of decreased pollution levels and improved environmental regulation, freedom for women and gays, increased IQ and health stats, better longevity, education.

The golden age would be more of the same, an end to armed conflict, democracy for all, much less religion and superstition, stopped population growth, a decrease in global footprint.

"We" would be humanity.

I think this statement is non sequitur, among other things.

1. I convinced there are limits somewhere.

2. Any very advanced species should be able and might be willing to cover up its tracks.

3. We might be first tech civilisation in the observable universe. Or at least, the light from other tech civilisations might not have reached us yet.

I think there might be a Kuznets curve to that. The 17:th century Europe might have been fairly bad, and hunter-gatherer life might have been good to native Americans. But now, modern life is even better and will continue to become better. Also, even if hunter-gatherer life was better than modern life will ever be, which I doubt, that's irrelevant. We won't go back voluntarily.

*ding ding* "We have a winner!"

(Perhaps especially insofar as some of us have a thing for myths and misconceptions, etc....)

One of my faves:

Civilization! - *Some Restrictions Apply

(I imagine people will appreciate the depictions of "freedom" therein, including women and gays of course.)

Feeling a little studious?...

Get your 'modern nutritional progress' right here:

The Seven Myths of Agriculture

There's your golden age right there in bold, jeppen.

Worth repeating. ;)

In response to Zerzan's theories, it's important to remember that anarchism is simply unworkable without a fundamental rewiring of humanity's psyche. Any society that embraces anarchy will be at the mercy of any nation state willing to exert itself to conquer the anarchic society. While we may be able to learn from hunter-gatherer societies to improve our modern relationships and habits, the notion that anarchy will triumph over nations is as realistic as assuming that multi-cellular lifeforms will lose out to their single-celled ancestors. I'm not discounting his ideas, and I think that there is compelling evidence for the idea that agriculture may have resulted in an impoverished existence for the average human. However, agricultural societies dominated the globe for a reason - agriculture resulted in more energy available for consumption, and thus agricultural societies were more powerful.

I also enjoy Illich's work, but the critique you bring up is entirely negative. As an engineering scientist working in health care, there is much in institutionalized education that is valuable, and there is a growing emphasis in healthcare on actual health care and preventive medicine. I am surrounded by people, products of our educational system, working to produce new therapies. Modern medicine's ability to deal with cardiac disease and cancer are evidence of our successes. Additionally, the health care system is beginning to emphasize preventative care and lifestyle choices. My sister is working on a research project that involves community outreach in an attempt to teach healthy habits to prevent diabetes in at-risk populations. What's especially interesting is that the modern health care system is now attempting to engineer populations to effect a permanently altered set of habits in order to achieve a higher quality of life. Perhaps this shifting emphasis came about in response to criticism by people like Illich.

Much of modern society does seem to be an unnecessary rat race, and there are large inefficiencies in many (if not all) of our cultural systems. It also seems clear that we are headed for an age of adversity and resource scarcity during which society must adapt to become more efficient. Some societies will be unable to adapt and thus will fail, just as many species became extinct during previous global cataclysms. However, looking back at previous great global extinctions that nevertheless led to systems of increasing complexity, I can't help but think that the process will continue.

"No enemies have ever entered Ankh-Morpork.

This is not entirely true. Technically they have, quite frequently; the city welcomes free-spending barbarian invaders, but somehow the puzzled raiders always find, after a few days, that they don't own their horses any more, and within a couple of months they're just another minority group with its own graffiti and food shops."

I think that the probability of singled celled life forms inheriting this planet from multi-cellular creatures is actually quite high given what we know about the history of life on this planet. Nature doesn't seem to share our biased thinking that more complex is always more fit for long term survival.

The history of life on this planet has resulted in ever-increasing complexity, eventually resulting in humanity and the rise of culture and cultural evolution. All previous mass extinction events failed to eliminate complex life, and they also failed to reduce its complexity in the long run. Perhaps a graph of complexity (which is itself a fuzzy concept) versus time would look sawtooths ramping upwards, with extinction events temporarily knocking back complexity, but science has yet to describe an event which wiped out multicellular lifeforms. Perhaps such an event took place very early on, before multicellular lifeforms were widespread.

It is somewhat plausible that all societies completely collapse, but it is far less plausible that all of humanity is completely wiped out. It is even less plausible that all multicellular lifeforms are wiped out. I'm a little surprised that you'd propose such a scenario.

It's amusing that, in all our complexity, we end up as cogs-- cells or specialized organs-- in a machine without a brain. I'm being a little poetic here, but just a little...

So that, instead of Gail the Human Being, we have Gail the Actuary. Humans do more than actuaries. Actuaries-- jobs, careers, professions-- are glorified obsessive compulsive disorders, relatively-speaking.

"Hi, I'm asinine, the lower-bowel."

Amusing, certainly, but it fits within the framework of increasing complexity. We don't generally think about the violence involved in the taming of the mitochondria, or the fact that the development of multicellular life did not entail purely cooperative relationships. There is certainly of violence against the individual human inherent in societal structure, and it will require much time before human and societal evolution converge such that we can create a society through purely voluntary interactions. Consider the human individual from the point of view of the cancer: why should this body restrict my right to grow and thrive? The cancer results from a change in its basic operating system that causes it to ignore outside control. We view it as something to be eliminated because it does not mesh with our desires. Similarly, there are many cultural elements we view as destructive or unnecessary and we are actively working to eliminate them.

Why should we be more than actuaries? The vast majority of human desire is bestial in nature. I do not accept for granted that we should set the individual as the ultimate goal.

And here I was under the impression that you'd care more about other claims like:

I agree, the nuclear numbers are also fairly happy.

Agriculture and food production is not that big a problem, sustainability-wise.

It seems the human population will stop growing at 9-10 billion. There should be no major problem feeding that many sustainably using modern techniques.

Given your past postings I'm shocked you didn't respond to:

When necessary, agriculture can produce its own energy and hydrocarbon feedstock from its biomass.

Here's a gent stating that organic production should be converted into chemicals VS your past position of organics -> compost and you didn't bat an eyelash.

And to claim:

fortified or replaced with energy and hydrogen from nuclear

The regular TOD reader, upon seeing 'if the organics come up short - use fission power to make up the difference' and comparing to your past statements Tribe, its like you don't really belief what you've argued for so passionately in the past.

I didn't read the whole thread.

But as we both know, with each new generation, the knowledge reset button is pressed, never mind the headache of "reality", itself, (and the ongoing programming) which follows us to the grave.

Nevertheless, it's important to keep in mind that jeppen is 'fairly sophisticated'. (Hugz and lingonberries. :)

If you take your last paragraph and aim it back toward your first two, you may consider that it shoots them up, maybe like a bad old western movie gunfight.

(Tribal/Band) Anarchy appears the undercurrent that runs us, asinine, and the state is, itself, in its own anarchy anyway, apparently. Like a toppling tree-fractal. Trees fall; seeds are dispersed...

Does the social or collective fight with the individual or does it get along? Utopia says it gets along; dystopia that it doesn't. We seem to be flirting with the latter. Take a look around. If you can't see it, then try taking a few steps back from the pointillism.

Read my previous comment. See also.

We're being played. ;)

Jeppen, you can't possibly be serious! No matter how much you may think you can improve food production through GMO technology, at some point you are still going to be faced with insurmountable physical and chemical limits. Not to mention all the inherent risks of basing our survival on a very few GM monocultures in a world that has been ecologically devastated. Anyone who thinks BAU with 9+ billion humans on this planet is sustainable or desirable has simply been ignoring reality.

Might I suggest a primer in basic ecosystem thermodynamics.

http://www.uni-kiel.de/ecology/users/fmueller/salzau2006/ea_presentation...

Have you hugged your bag of NPK today?!

I'm very serious.

If we look at the ecological footprints graph, we see that everything but the carbon part is almost flat since 1960 even though the population has exploded, and everything but carbon emissions fits very well within the carrying capacity of the Earth. This fact is due to the amazing revolution of modern agriculture, and this revolution is far from done. GMO and modern agricultural practices has yet to improve large parts of the world's agriculture.

I think the footprints graph prove you wrong. If we solve the carbon problem, we're basically in the clear and can even shrink the rest of the footprint with better tech. Yes, we still have to manage different kinds of pollutants, and we would benefit from reverting to sustainable fishing and so on. (I.e. we would get larger catches if we weren't overfishing.) But these are manageable problems.

You may, but it doesn't help and your link basically said nothing at all, as is usually the case when thermodynamics is invoked in the context of sustainability or peak whatever. I don't know what it is with thermodynamics that make people think they have a profound understanding of everything after reading a little about it. It isn't more relevant than, for instance, quantum dynamics. Even though they are both fundamental principles that govern all things, they are the wrong levels of abstraction here and says nothing of our limits.

GMO and modern agricultural practices has yet to improve large parts of the world's agriculture.

Perhaps because GMOs don't result in yield improvement - just profit improvement for the vendors.

TRUTH: GM crops do not increase yield potential – and in many cases decrease it

You will have a field day with this one, but still, I'll be lazy and cite the evil ones themselves, i.e. Monsanto's rebuttal.

Again, if one were a bit lazy, one could have a look at the rest of the "myths" claimed in your link, apply some critical thinking, and quickly deduce that either we have an epic conspiracy on our hands, or the people you link to just cling to every little straw of bad science and nutty pseudo-science they can find to discredit GMO.

Btw, Mark Lynas recently apologized for being anti-GMO.

GMO, meet biochar, biochar, GMO. My god, we really have our work cut out for us as a species.

I'll take a slice of Mad Max meets Bladerunner, please, with a dollop of Soylent Green and a splotch of Eraserhead. And another for my... kid... whose playing in The Matrix...

..."What was that honey? ...Oh yes of course, you may accept blue candy from gentleman in nice suit with crisp white shirt and sunglasses... Don't forget to say thank you..."

So you don't have actual data supporting your position - just rebuttal when you are challenged?

Mark Lynas recently apologized for being anti-GMO.

Is this some kind of appeal to authority argument? Why should anyone one care about Mr. Lynas when Mr. Lynas was anti-GMO VS now?

I agree. Farmers do GMO because they are tricked or coerced by Monsanto. And the fairly common piracy of GMO crops, of course, is even more of a folly since GMO lowers yield and increase the need for inputs. The lower price of GMO products doesn't say anything either, as price says nothing about yield or inputs.

Ordinary breeding can be positive, but the increased speed, precision and freedom with which to combine specific genes of organisms using GM is just confusing to the poor scientists. They don't have a clue what they are doing and cannot possibly improve on the work of Mother Nature.

Reminds me of a Watchtower paper a Jehovas Witness gave me. It claimed GMO is like stirring the insides of a broken radio with a stick. "This doesn't make it better." Complete with a picture of an open radio apparatus with a stick in it. (Yes, I know this is called "guilt by association".)

Right! Everything I've read says that the apparent increase in yield is because the plants can make use of increased inputs, not an increase of output with no additional input. More fertilizer and nutrients needed to get more out. Your article shows the so-called increased output comes at a cost of less what I'd call "efficiency".

I've read says that the apparent increase in yield is because the plants can make use of increased inputs, not an increase of output with no additional input.

And I'm sure our resident expert will show exactly how GMOs and only the GMOed things have this yield increase and how with his expert study he'll have seperated it from other variables.

Next up on the techno-fix bandwagon to boost yield will be hooking up the plants to electrodes to make 'em grow better no doubt.

Try reading this:

http://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/gmo/reports_studies/docs/economic_perform...

"Assessment of the economic performance of GM crops worldwide", by the Univ of Reading and the Swiss Federal Inst of Technology-Zurich, 29 March 2011.

Excerpt: "Due to the strong variations between regions and the additional varying factors found in the analysis that influence results on the economic performance of GM crops (see above), any generalised conclusions on the economic performance of GM crops for the whole world would inevitably be misleading. However, positive economic effects have been observed for a number of countries, which is in line with other review studies (e.g. Carpenter, 2010, Gouse et al., 2009, Bennett et al., 2004a, Frernandez-Cornejo et al., 2005, and Qaim, 2009) and explains the high adoption rates of GM crops in these countries."

Cheers.

Concerning the graph, the amount of cropland in use being approximately constant over the last 50 years indicates little about the total land that could be cropland and how much has been degraded.

The Future Prospects for Global Arable Land, Future Direction International, 19 May 2011

At that linear rate of degradation humans have about 65 years before using all the available arable land at which time the "cropland" wedge in the graph will begin contracting. The Limits to Growth model warns this ruining of arable land is not sustainable.

I don't understand your 65 years. 22% has been degraded over ~65 years. According to your link, 1.5 billion hectares are currently used for crops, and 2.7 billion hectares has the potential. More than 65 years should pass before we're down to 1.5, right?

You guys understand that much cropland is not likely farmed by you, or even a traditional/local farmer, right? That it's likely farmed by some entity you don't know, and in which you have little say with regard to how things operate? And you have some understanding behind some of the implications behind the model/system under which those crops are farmed?

If 2 billion hectares were ruined in 50 years (one could pick 60 years because it stated 1950's, not 1950), then an average of 40 million hectares are ruined per year. At that rate 2.7 billion hectares would be ruined in 67.5 years using up the currently unused arable land. I rounded down to 65 years because the data was published in 2011.

If 2 billion hectares were ruined in 60 years, then 81 years is needed to ruin 2.7 billion hectares.

But you're then comparing apples and pears. The ruined area included more land. Again, look at the 22% figure.

Note that I was talking specifically about how thermodynamics applies within the context of ecosystems and not as some abstract general principal. Even Agro industrial production of GM monocultures are still subject to increasing entropy so while you seem to disagree about the relevance it is actually highly relevant in the context of limits.

http://www.ibiblio.org/london/agriculture/forums/sustainable-agriculture...

Two things:

1. That something isn't done sustainably does not mean it can't be done sustainably. It's not very strange that you do it unsustainably for a while until you hit limits, and then you adapt as necessary. Every time I eat dessert, for instance, I do something unsustainable to my body. So after a while I get full and react to that by stopping and reverting to eating nothing (which is also unsustainable, so after a while ...).

2. Agriculture can be sustained energy-wise by renewables. Water can be had by desalination, also powered by renewables. Soil can be improved by rotating crops, letting the fields rest and by adding dung, for instance. And if all else fails, nuclear power can provide the energy until the Sun goes red giant.

Hi Jeppen,

Two quick points. I too try to be optimistic (though not quite at your level of optimism), but I try to maintain some level of realism.

First, the graph you posted (which you will claim is not correct in any case) only shows data through 2006, carbon emissions have continue to increase by 2.5 % per year through 2012.

Second, you assume the carbon problem will be "solved". This is by no means clear. It might be "solved" by running out of fossil fuels, but such a "solution", is likely to lead to 4 C warming above pre-industrial (lets say 18th century mean) temperatures, possibly more. You might argue that such temperature increases would be beneficial, I would argue the reverse and believe that a majority of scientists, (particularly biological and ecological scientists (who would know best) would agree with me.

DC

When I say that CO2 emissions will be "solved", I mean that yearly emissions will go down to sustainable levels within a hundred years or so due to depletion and political action. However, the cumulative emissions before this happens will be (is) triggering a catastrophe of a fairly large scale. I hope it won't be as big as undoing our civilisation.

Are they serious with almost flat fishing footprint since 1961?

And with such a methodology - are they serious with the rest?

And is that fishing somehow "sustainable" cuz it is under that "1 Earth" line?

There should be no major problem feeding that many sustainably using modern techniques.

Do you have proof of this, or just faith?

Please have a look at the global footprint graph I posted.

Is that your "proof"?

I wouldn't call it proof, but isn't it the best we have? I'm sure the footprints calculations will be revised and improved in the years to come, but I don't expect them to ever be exact or rigorously proving anything.

If you have anything better (quantitatively, not hand-waving, please), I'm willing to listen.

I wouldn't call it proof,

So then your statement is one made on faith.

but isn't it the best we have?

No. Until terms are defined and assumptions agreed to as "what is modern agriculture" the end result will be like the Fission is safe discussion with one position of 'fission plants are safe because no one dies in them' and when data gets posted that is in opposition to your position it will be called "nutty pseudo-science" even when the link says:

(silly USDA and their nutty pseudo-science).

Right off the bat there are "issues with terms"

Lets re-look at the pull-quote: feeding that many sustainably using modern techniques.

If 'modern techniques' are the use of petroleum derived herbicides and pesticides, how do those chemicals fit with the definition of 'sustainably' as commonly used?

I'm willing to listen.

I'm going to state that here I think you are lying and being disingenuous,

I was wondering if your claim was based on actual data or just faith or perhaps a word salad and I have my answer.

Yes, I do have some faith in the ecological footprint calculations. I'm sorry you feel they are hogwash, but since you can't come up with anything better, we are stuck with you hating everything that can be interpreted in a positive way and me trying to point to what data we have available.

That you linked to a crazy-house featuring a non-referenced claim about USDA is worth very little. Anyone can make such a claim. It need not be true, or it can be twisted, exaggerated and taken out of context.

Quite well. When necessary, agriculture can produce its own energy and hydrocarbon feedstock from its biomass. (Preferably, for the environments sake, fortified or replaced with energy and hydrogen from nuclear and so on.)

That's part of your pathology, I think. I don't think you are lying and being disingenuous. I just think you have some kind of deficiency (I'll abstain from speculating on the exact nature of it) that make you especially subjective and unreasonable. I've seen it before from you in several contexts and regarding several topics. You choose your truths based on what fits your shallow world view and then that's that. I think you're being completely honest, though.

That you linked to a crazy-house featuring a non-referenced claim about USDA is worth very little.

From the web page cited:

http://earthopensource.org/index.php/5-gm-crops-impacts-on-the-farm-and-...

See the 6? That indicates an actual reference.

Now at the bottom of the page there is a link to this:

http://earthopensource.org/index.php/5-gm-crops-impacts-on-the-farm-and-...

(For references, please click here. is the text where one can find the link.)

And from the references:

My mistake, missed the reference links to the right.

However, you still referenced a crazy-house site, and the quotes you refer to are taken out of context from the original report and pasted together with a "..." in-between to make a completely false impression.

The first part continues: "In fact, yield may even decrease if the varieties used to carry the herbicidetolerant or insect-resistant genes are not the highestyielding cultivars. However, by protecting the plant from certain pests, GE crops can prevent yield losses compared with non-GE varieties, particularly when infestation of susceptible pests occurs. This effect is particularly important in Bt crops."

The second part continues: "Both herbicide-tolerant cotton and Bt cotton showed positive economic results, so rapid growth in adoption is not surprising in these cases. However, since adoption of herbicide-tolerant corn appears to improve farm financial performance among specialized corn farms, why is its adoption relatively low?"

And in the conclusion section of the reference report, it is stated that: "All in all, we conclude that there are tangible benefits to farmers adopting first-generation GE crops."

So that was that.

Yair . . .there are lots of numbers about land degradation being tossed back and forth and to some degree I believe it's a lot of cobblers.

You blokes are looking at the Agro-business big picture and when the SHTF that will all be irrelivent.

I'm on the east coast of Australia and I can tell you there is enough land and water to produce all the seasonal vegetable produce needed within a hundred kilometer radius of all our major towns and cities.

. . .take that out to one hundred and fifty kays and you can include some grains

The proviso it has to be small scale farming. It can be done with solar or mains powered equipment such as our "Circle Worker" concept . . .but as with all simple things that could be done it will probably take a while for the population to realise small scale farming is a good, satisfying and honourable profession and doesn't have to be that hard.

Cheers.

A more directed question ... Is Malthus wrong if six billion of the seven billion people on earth were to starve to death tomorrow ? ... curlyq3

And the final question is ... Is human extinction necessary for Malthus to be "Right" ? ... curlyq3

curly - valid points IMHO. I'm glad Gail is leading the discussion because I don't think I've seen her take on an aspect of supply/demand that has surfaced recently on TOD. If I'm looking at the world upside down she can straighten me out. LOL. One simple question: is it possible to ever "run out of" any commodity on this planet? One of the problems with such discussions IMHO is the use of such phrases. While it seems to imply much it doesn't really say anything. We will never run out of food, oil, fresh water, etc, etc. IOW demand will always be met by a sufficient amount of supply. That's true IF you accept the definition that demand is what one can afford to pay for...not what you want/need to acquire. Obviously price will moderate the balance. In the days of Malthus as well as today there were huge numbers of folks going hungry. And many dead as a direct result of malnutrition or its side effects. For these folks the world did, and has, "run out of food"...the world has run out of food they could afford to buy.

Just as there are millions who have run out of oil not just today but decades ago. If you live in NY, lost your job and can't buy heating oil the world has run out of oil from your perspective. And when the day comes when oil is $200/bbl and global production is half of what it is today but a person has access to and can afford to pay for his fuel oil delivery then the world hasn't run out of oil. And never will for those that can pay for it.

But there's other scenarios where a buyer has the funds to pay for oil but has no access to it. Some form of embargo would create such a situation. Another circumstance would be the result of a country, such as China, buying a number of the world's fields and removing them from the market place. Or having large supplies under long term contract. Or having the right of first refusal as part of a loan arrangement with an exporting country. But none of these possibilities represents the world running out of oil...at least from a Chinese perspective. OTOH from the perspective of a country that has no opportunity to buy oil the world has run out of oil. Thus back to why I consider such loose terms as "running out of X" to be rather meaningless. Why I've also come to the conclusion that the actual date of PO is also rather unimportant. Maybe we did reach PO in 2005. But every oil consumer in the world has all the oil available to them today that they can AFFORD. Excluding local distribution problems not one American has been denied an ounce of gasoline that they could AFFORD to pay for. For these citizens not only has the world not run out of gasoline but it's not even in short supply: they can buy as much as they want...as long as they can afford it. Equally unimportant if PO doesn't occur until 2030 for a consumer today who can't afford the current price of oil. From their perspective the world has not only reached PO but has gone far beyond...the world has run out of oil.

Howdy ROCKMAN ... I always look forward to your posts here ... my grandpa would tell us your as free as your money will take you in this world ... our comfort and survival is circumstantial ... curlyq3

And the current unemployment rate in the US is about 8% if you don't count those who have given up trying to find a job...

This is my employment as a percentage of US population graph that I have posted in several Our Finite World posts, including Energy Leveraging - An Explanation for China's Success and the World's Unemployment.

The part I find disturbing is that the US employment percentage started decreasing very close to the same time that China's energy use started ramping up (which in turn was right after it entered the World Trade Organization in 2001).

There was a little somethin' which happened in September of that year...

The downturn starts before that...around the time of the "DotCom" bubble burst. IIRC that caused a real ripple through the economy and pulled a lot of investment capital out. Then we got the Bush Tax Cuts in 2001 and a redirection of government spending into the (low return on investment) War Machine.

Good points! The Bush Tax Cuts didn't really help the job situation much, did they? Of course, hiring a few more for the military "helped" in some sense.

The other thing happening here, I think, is job outsourcing to China, as stuff is made in China it isn't made elsewhere.

Gail,

A much better metric is the ratio of employment to working age population rather than employment/population.

See http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/01/13/notes-on-japanese-numbers-bo...

DC

It has nothing to do with China.

The employment percentage fell in 2001 because a recession started in 2001. Look at the chart -- every recession results in a fall in the employment percentage.

The employment percentage has been in long-term decline due to simple demographics -- aging baby boomers -- as the BLS data clearly shows:

* Participation rates are highest for age 25-34 and 35-44, slightly lower from 45-54, and much lower from 55-65.[1]

* Population in the 25-44 age bracket fell from 2000 to 2010, but increased sharply in the 45-54 and especially 55-65 brackets.[2]

As a result of these two facts, it was inevitable that the US's labour force participation rate (and, hence, employment rate) was going to fall between 2000 and 2010, and will continue to fall from 2010 to 2020.

[1] http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_table_303.htm

[2] http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_table_302.htm

But of course. Outsourcing manufacturing jobs to places that pay one tenth the US wage level has nothing to do with it. All those steel mills, all those cotton mills and every other kind of mill has moved overseas because the baby boomers have aged.

And all the time I thought it was because of the wage differential. Silly me.

Ron P.

That's hyperbole, but it's almost true - the BLS data clearly shows that demographics is driving the decline in the employment ratio. I'll briefly summarize what that data shows:

Labour force participation fell by 2.4% between 2000 and 2010. If we take the 2000 participation rates and the 2010 population mix, we still get a fall of about 1.3%; in other words, more than half of the difference is due to a shift in the demographic mix. The employment ratio always falls during a recession, as the original chart indicates, suggesting that most of the remaining 1.1% is likely due to comparing an economic peak (2000) to an economic trough (2010).

Please feel free to look at that data yourself if you don't believe me. It's simply a fact that the key here is an aging population.

Life cycle economics are helpful up to a point but I am not sure that demographics only explain what is going on in the US. It would be interesting to look at other areas like Japan and Europe with respect to employment. I know that in both of those regions the ration 19-65 vs the rest is declining but I haven't looked at employment rates.

Rgds

WeekendPeak

This issue is high oil price. This leads to higher food prices in addition. These higher prices "messes up" the financial system. People don't understand that what they should be looking for is a financial system problem, not a physical shortage of oil.

One article I wrote about this subject is Our Oil Related Fiscal Cliff. (I don't think I ever submitted this to TOD. )

Another issue that is important is the fact that the dollar is the world's reserve currency. If this should change, it would have huge ramifications, practically overnight. I have recently been reading about how the dollar becoming the world's reserve currency in 1944 helped enable greater world trade and also allowed the US to amass greater and greater debt at ridiculously low interest rates. (See this recent ASPO-USA post by Erik Townsend--very good, but long.) This timing also helped enable the growth of world oil use--something I didn't think about when writing the current post.

One problem we are running into now is that the US as the world's reserve currency is clearly unsustainable for the long run. For one thing, the US is amassing so much debt--in excess of 100% of GDP--that something has to give. For another, if the world ever becomes "oil independent", the Saudis (and others) will have not motive to price oil in dollars. In fact, the US is already becoming less and less dominant as a buyer of world oil.

At any rate, if the situation of the world as reserve currency should change, this could increase the US' interest ate for borrowing money to that that it really should be--I am guessing in the 5%+ range. The higher debt payments would mean that interest payments on debt would suddenly become a much larger ($500 billion to $1 trillion) larger source of outgo, and mean that the US budget deficit is a whole lot worse than currently advertised. US would be much less able to compete in world markets.

None of this would look like peak oil, but it really is.

Hi Gail,

Most US debt is held by US citizens. Higher interest payments would be payments to US citizens, the idea that most US debt is held by China is a fallacy. The US budget deficit is also much less of a problem than many think. See

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/01/10/the-mostly-solved-deficit-pr...

As far as unsustainable debt, consider Japan, see

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/01/11/is-japan-the-country-of-the-...

Japan is often held up as an example of the problem of a high debt/GDP ratio, but after about 20 years of high debt/GDP, we are still waiting for the catastrophe.

DC

We can see limits on many things. It is hard to see in advance exactly when those limits will kick actually kick in. The fact that the debt has continued to be repaid so far mostly means that adverse events (like high oil prices) haven't kicked in to a significant enough extent yet as to push countries over the "edge".

Reinhart and Rogoff's book, This Time is Different looks at actual debt experience of countries. They debunk the popular belief that internal debt doesn't matter. In the US, large debts are owed to the Social Security trust fund, to pay benefits. (Money that people paid in for Social Security benefits has already been spent on something else, leaving no real cushion when the baby boomers hit retirement!) Defaulting on these bonds will mean less income to Social Security recipients. Isn't this a problem?

Reinhart and Rogoff mention that 40% to 80% of GDP are normal debt to GDP ratios. I believe that they also say that above 90% is in the danger zone, or something like that--didn't see the exact reference now. According to the US Treasury, US Debt as of December 31, 2012 was about $16.4 trillion. We don't know what the GDP for the year will be yet, but based on data through September, $15.5 or $15.6 trillion would be a reasonable guess. If we use $15.6 trillion as the denominator, the US will be at a ratio of about 105% at December 31, 2012. (Sometimes people get confused by government debt that doesn't include amounts to that are not in publicly traded bonds, like debts to Social Security, and get the current US debt too low. Federal Reserve Z.1 data for example leaves out this debt.)

This is the real reason that all the politicians keep mentioning "entitlements" when talking about the debt. Though Social Security and Medicare are separately funded through their own tax, the "Trust Fund" has absolutely nothing in it. Can you imagine if Al Gore had been selected by the Supreme Court and gotten his Social Security "Lock Box?" (and two wars and likely 9/11 wouldn't have happened because Gore wouldn't have re-assigned the intelligence agencies to Iraq as top priority).

So what are politicians to do? Cut benefits to hide the fact that they've been stealing from Social Security for years and years. That's why they keep coming up in these discussions. If they raise the retirement age by 2 years they, on average, get to steal another $28,000 per person more before getting caught.

There is a partial excuse behind the "stealing from Social Security" problem. As much as we would like to be able to "prefund" retirement benefits, it doesn't really work well in practice, at least on any very large scale. The stock and bond markets of countries are not large enough to hold all the funds that would need to be invested. (Perhaps they could hold the planned prefunding to help smooth out the jump in benefits, caused by the boomers retirement, though.)

Behind this prefunding problem is an issue that many people may not have stopped to consider. In a given year, say 2020, retirees have to live on whatever food, clothing and other consumables are produced in that year. In fact, in 2020, the whole world's population will pretty much have to live on what consumables are produced in 2020. If the amount of those consumables is lower in 2020 than it is now, that is too bad--that is all we will have (adjusted for whatever carry over from prior years there is). If retirees get 1/3 of the consumables total, then the rest of society will get 2/3 of the total. The taxes on the rest of society will need to be high enough to pay for what the retirees get.

Our financial system has given us the impression that we can put away money and save for tomorrow. That is only true, if enough goods and services are being produced to cover these promises. High oil prices and low growth in oil supply tend to depress economic growth. The low economic growth in recent years makes it very hard for any kind of pension program or any kind of benefit such as Social Security to work as planned.

The US is already 5% with 25% of most everything already. That is 5% of the world population consuming 25% of the world's (name anything). I'm not sure how having Social Security funded would result in the problem you mention.

There is, however, a curious point which you've conjured...if the fund were actually pre-funded in total, set aside in the "lock box," then that would have the same economy-stagnating effect that the mill/billionaires and corporations/banks are having accumulating all of the capital and not spending it - since that money, too, is not available for circulation (money doing "work"). I'm thinking things would equalize after the initial "charging" phase of the "lock box" and the money would eventually go into circulation as people retired - but it would be distributed fairly equitably as everyone who retired would get it to spend.

Gail, I too have worried about this. I don't think a lot of citizens have even thought about the issue.

There were a couple of folks who brought the US reserve currency issue at the ASPO-USA conference as well. Quite a few people know a bit about the subject, but not too much.

If/when China decides to float their currency there likely is going to be a significant impact on the status of the US dollar.

Rgds

WeekendPeak

Hi Rockman,

I also look forward to your posts.

Peak oil is simply that the current flow rate cannot be increased any further. How the produced oil is distributed is not really part of the equation. At least to my mind it is conceivable that at some point (my guess would be 25 years or less) that no matter how high oil prices rise that no higher level of production of petroleum liquids (C+C+NGL) per day (in barrels of oil equivalent=5.8 million BTU/barrel) can be reached. The price is just a convenient way to ration available supply and is better than a planned economy (Soviet style). IT MIGHT be nice if oil were free so that everyone could afford as much as they would like, but I am certain that not much oil would be produced if the price were zero.

I think that it is important for people to realize that we may reach PO as I have defined it and sooner than some (Yergin comes to mind) would think. It would be better to start to prepare 20 or more years in advance.

From your perspective as a geologist with far more knowledge than me of what is likely to be possible, do you think we will reach peak oil (as I defined it above) by 2020 even if real oil prices increase by 12 % per year (reaching $240/barrel in 2013 dollars by 2020)? This also assumes there is no worldwide economic collapse in the meantime. Thanks.

It occurs to me as I re-read my comment that I am missing your point. Are you implying that peak oil is likely to be reached because of a lack of demand as prices rise rather than the lack of ability of producers to supply oil at any price? If that was your point, I tend to agree. If one postulated one million dollars per barrel as the real price of oil, we would see a lot of oil produced, but not very much demand. My scenario above is based on $20/ barrel in 1998 rising to $100/barrel in 2012 (inflation adjusted dollars) which is a 12 %/year increase in price, which I extended out to 2020 to come up with $240/barrel. My optimistic assumption is that this price increase does not crash the world economy.

If we start at 2004 ($44/barrel) and prices increase by 11 % we get to $101/barrel in 2012 and $234 in 2020. World C+C increased from 72.5 to 75.5 MMb/d (EIA data, 2012 estimated) from 2004 to 2012 which is an increase of 0.5 % per year, if that trend continues we would reach 78.5 MMb/d in 2020. I think it likely we will be on an undulating plateau from 2015 to 2025 at 76 to 77 MMb/d, with high enough prices we might extend the plateau out to 2035 at most with decline thereafter at any reasonable price (lets say less than $2500 per barrel in 2012 dollars, note that the 11 % price rise gets us to $1100/ barrel by 2035). At one point a few years ago it seemed your position matched this scenario fairly closely, lately you seem more pessimistic.

DC

DC - " How the produced oil is distributed is not really part of the equation". I suppose that depends on what equation concerns you. What concerns you more: how much global oil is being produced in 2020 or what you'll have to pay for all your energy in 2020? Personally I don't care if we've reached PO 7 years ago or if it's another 15 years out. All I'm concerned about is my supply and what it will cost me. If I can outbid 99% of the rest of the consumers out there PO doesn't exist for me and never will. Conversely that's what I meant about affordability: in 1971 when oil peaked in the US if you couldn't afford to buy a tank of gasoline does it make any difference to you if the US is producing more oil than ever before?

"Are you implying that peak oil is likely to be reached because of a lack of demand as prices rise rather than the lack of ability of producers to supply oil at any price?" I haven't thought of it in that context but at first blush I like it. How would that work: higher oil prices lead to the development of more production but depletion still reduces the amount of the oil that was cheaper to develop. Along, of course, with the more expensive oil from recent production gains. So to prevent a peak even more of the expensive to develop oil needs to be brought on line but the higher oil prices create demand destruction which reduces the amount of oil that can be purchased and thus reduces production rates. Sorta like the old question about a tree falling in the forest: if there is no one there to buy the oil (or hear the tree fall) is there a PO (or the sound of a crashing tree)? If folks can't afford to buy oil does it matter whether we've reached or past PO?

But with the time lag factor balance is difficult to achieve on any one particular day. But in general some equilibrium should be reached. As you say it doesn't matter if oil prices rise to $BIG BUCKS per bbl if no one can afford to buy it? I'm sure we could bring more oil on line if the price goes to $200/bbl. But how much oil? More than we were producing but would even $200/bbl oil offset decline of existing fields indefinitely? Maybe not. There is a finite amount of oil that can be developed at $200/bbl. How much I wouldn't guess but it's probably fairly limited IMHO. And then what when those reserves are developed?

But back to your point: how much demand would there be in the US for $200 oil? Easy to guess not nearly as much as $100 oil. So companies only produce a limited amount of $200 oil. Maybe that's another concept to toy with: PO$X. IOW when did we reach the peak of $50/bbl oil? $100/bbl oil? Need to wrap my head around that for a bit. Back in 1986 or so when the KSA opened their valves and drove much oil down to $10/bbl the world was producing much less oil than now. Was that the date of PO$10? IOW if oil stayed at $10/bbl how much new oil production would be developed? I imagine very little if any. Global oil production had a short lived peaked when oil hit $35/bbl back in the late 70's or so. Was that PO$35?

From 2005 global oil production has been fairly flat compared to the long trend. Bent ranged from $40/bbl to $140/bbl during that time span. So was PO$140 in 2008 and PO$40 just 6 months later? Does the concept of PO production linked to a price even make sense? Again, dealing with the time lag and rapid changes in demand with price instability can any quantitative relationship be considered?

I just wrote this stuff and I'm not sure what I'm saying. You have a clue? LOL.

Rockman,

Thanks for the reply. I think I understand what your saying. But to be sure we are on the same page, let me clarify my thoughts here.

First, I brought prices into the concept of peak oil mainly because you often say that when we talk about how much oil can be produced price matters, more gets produced at $100/barrel than $30/barrel (for example in the Bakken and Eagle Ford plays).

When I think of peak oil, it is really independent of price. From a logical perspective the price level will not be infinite, it is unlikely to rise above $1500/ barrel in 2012 dollars by 2035 in my opinion. Let's assume there is enough demand for oil in 2035 that crude oil prices actually reach this $1500/barrel level, I contend that if peak oil has been reached that world oil output in 2035 will less than the highest annual level previously reached and that it will never surpass that previous high, no matter how high prices rise. (Note that I expect PO will be reached before 2035, I think it is remotely possible that a plateau is maintained from 2015 to 2035, suffice it to say we will be past the peak by 2035.) In fact a rise in price will simply ration available supplies amongst the highest bidders.

So by my reckoning there is not PO at $140 or PO at $240, there is just PO. Also it is not PO for you or PO for the guy behind the tree, it is PO for the world.

You often say you don't care when PO is, whether 2005 or 2035. It doesn't really matter I suppose, but if knowing that PO will arrive at some point causes the world to more aggressively move to alternatives, it would be useful.

Even if the mainstream media never accepts peak oil until it arrives, rising prices might lead to a move to alternatives, but it will be too little too late.

DC

DC - I think we see the world in a similar light. But a hypothetical, if you please. How would your actions going forward from today be if PO definately occured in 2005? And if you knew for a fact it would happen in 2025? The same? If different in what way?

And would you expect the world would act differently if they were completely convinced PO happened in 2005? And if they were convinced it wouldn't happen until 2025?

I would argue that you and the world wouldn't change their actions in either case. Our actions, or reactions if you please, are controlled by the POD...the Peak Oil Dynamic. We're creatures of the moment IMHO. And I postulate the POD is independent of the date of PO. And my proof: no one can offer definitive proof if global PO has occurred or not. And yet the POD exists today as it does. And the world's actions, as well as its lack of actions, are as they are.

Hi Rockman,

I think that awareness of peak oil does change behavior. I think many on this site have changed their behavior to varying degrees based on peak oil, global warming, and environmental degradation in general.

When the peak occurs is probably less important than society in general realizing that such a peak either is imminent or has already occured. Most people will not believe it until it occurs, so only in that sense does the timing matter, I am pretty sure the peak was not 2005, my guess is a plateau from 2015 to 2025, it may take until 2020 for people to believe the peak has arrived. Maybe prices in 2020 at $235/barrel (2012 $) will get people's attention. Can you define the peak oil dynamic, please?

DC

DC - Now I see how we differ: you have faith in human beings. HA! GOT YA!. LOL. To be consistent I don't tend to pay much attention to efforts to date PO. But I see folks present folks offer that we have reached global PO or at least on a global plateau that will have small up bumps. They may be correct or you're guess may be closer. But assume those other folks are correct and PO has occurred. Are we seeing any awareness of PO that changing behavior? Folks are fairly aware that smoking and drunk driving are fairly destructive habits yet that awareness doesn't seem to be changing behavior significantly. We can go on with that list adding more examples such as the awareness of eating too much leads to obesity.

Focusing on energy how many folks in the US really believe we just spent $trillions and countless lives to "export democracy" to the ME and not for the sake of oil? And are we seeing any significant behavioral changes as a result? Where we seem to agree is that the only hope for a significant change in attitude is a reaction to very significant events. And IMHO those events will happen in the context of the Peak Oil Dynamic: all those various manifestations of a declining fossil fuel base which are primarily all the economic and political ramifications . It might be a tad late at that point but that's what it will take IMHO. If God descended and she told everyone PO would definitely happen on 21 June, 2025 I wouldn't expect any significant change in behavior. But that's just me and my lack of faith in man's rationality.

Rock,

The way you define the issue of 'running out' makes a lot of sense to me. But then it begs a new series of metrics that allows one to analyze the situation per your perspective. How do we construct that? Maybe Gail can think up some formulas for us to use as the effects would seem to be measurable to some degree of accuracy.

If we look at real costs of energy and the rise to the point that X% of the population is priced out of the market could we create a series of formulas that approximates the effect that would have on food supplies, population levels over a variety of terms; short, med long? And effects on GDP, trade levels, climate impacts, etc.

There would, of course, be a host of interesting discussions on what happens in localized areas (counties) based upon their starting levels of affluence and internal access to energy resources. And, since the world is currently committed to a high level of integration and complexity, how much degradation of the periphery has to occur before even the rich locations start to feel the effects of our creeping Malthusian fate.

Wyo

Wyo

Wyo - And this is where the Gails et al need to lead us. I understand my little piece of the puzzel fairly well. But IMHO the BIG PICTURE takes a very multidiscipline approach to flesh it out into some meaningful form.

A big piece of being "priced out of the oil market" occurs on the business side of things. What happens is that the number of jobs (that use oil, and that allow the job-holder to purchase oil related products) tends to decline. See my post The Close Tie Between Energy Consumption, Employment, and Recession and my earlier post The Oil Employment Link - Part 1.

I try to write about the Big Picture on Our Finite World. The Oil Drum tries to stick more to the oil situation. It doesn't have reviewers with broad enough areas of expertise to evaluate posts that are very multi-disciplinary.

Really?

Rgds

WP

ROCKMAN, good point.

I differ with one aspect of this thread, the idea that there will always be a supply of fuel to keep things going. You cannot exclude local distribution problems, especially when those can extend across the country. I feel that the kingpin will be when the distribution network for the fuel supplies breaks down, and as availability starts to pinch and prices rise, systemic failure will happen.

I am old enough to remember gas rationing during WWII. At times there were some without fuel, except when they could get it on the black market or borrow from a friend. I remember lines of cars waiting to fill their tanks in the 70s, when I ran out of time to stay in line. Looking ahead, I see the time when the authorities must start to prioritize who gets fuel in order to provide basic fire and safety services. More and more people will simply not be able to get the fuel they want, and eventually, the fuel they need to continue their lifestyle.

I have been a full-time RVer for the past fifteen years, and I have learned to expect there will be problems down the road. I keep my fuel and water tanks full because there will be a time when I cannot refill them. It is not a matter of AFFORDing to pay for the resource; it is truly a matter of availability.

Now if you extend this problem into the real world of today, there will be the time when the fuel simply is not available, even it someone's life depends on it. That problem will only get worse and worse.

Where does this leave Malthus? His thought was on target, but his timing was off because a White Swan came along. Unfortunately, that Swan is losing its feathers; they are regrowing black.

sam (prudentrver.com and Was A Time When)

The other point I'd make in support of your systemic failure leading to genuine shortages situation is this: A hundred years ago, oil was super easy to extract. All you had to do was poke a hole in the ground in the right place and it squirted out. Very little technology required.

We have since used up those easy deposits and today, to get more oil out, not only has EROEI dropped, but along with this, the complexity, difficulty, and time required of the technology to get more out has gone way up. Now in the oil sands you have to build huge complex facilities to cook the oil in the ground for months, then process the goo that comes out, and then further upgrade this into something resembling conventional oil.

If there is a social collapse then what chance do we have of being able to construct and operate these mammoth operations? The second Mad Max movie had it wrong when it depicted a little oasis of society clustered around an oil well, with everything outside being anarchy. The problem with that Mad Max scenario is that we won't have any more oil wells to cluster society around; we will instead only have the option of gigantic complex oil sands facilities. These by definition require a huge amount of support from manufacturers and suppliers all throughout the rest of society and the continent. If that society is falling apart, then how will the oil sands facilities be able to be supported and expanded?

I envision fossil fuel extraction more like a siphon. Initially it gushes out but the as the liquid is removed the head drops. This then reduces flow rate. Near the end, the siphon gurgles and sucks air, barely staying in motion. Soon the minimum momentum cannot be maintained and the siphon breaks completely.

There are gravity drained stripper wells producing 10 barrels of oil per day that will slowly decline to nothing over the next 100 years. The operator needs replacement parts for the pump jack and some electricity to keep oil flowing.

Do you have an idea of how much production all these stripper wells add up to?

U.S. Dept. of Energy: Stripper Well Revitalization states:

which makes it 710 kb/d in the U.S. in 2008.

More information: Tech Talk - American Stripper Well Production, Heading Out, May 22, 2011

Was a Time When ... intriguing, but doesn't appear to be a link?

BTW, Sam, good to hear from you. Wish you'd drop in more often. The new site layout looks great! Still in SoCal?

I fixed the link for "Was a Time When"

I agree with you on systemic failure likely being a problem.

In Atlanta, we were very short on gasoline after both the 2005 and 2008 hurricanes. Part of the problem is temporary disruptions. At some point, it is going to be harder to repair these. If prices are held down, then supplies especially tend to run short.

http://youtu.be/b4r0uWvsopU

Happened all around the Southeast...having read TOD I managed to fill the tank when the hurricane hit and reports of damage started coming in that almost carried me through it. Had to wait in line one day for about 20 minutes to get 5 rationed gallons which (@ 40mpg) was enough to last me another two weeks. I was turning my engine off while in line and in the few places I could I was pushing the car (CRX - it's light)...all the while around me were pickup trucks idling which probably got 12 mpg on a good day with the wind behind them. A taste of what's to come, I imagine.

Sam - “…the idea that there will always be a supply of fuel to keep things going.” I didn’t notice anyone saying that. I know I didn’t. There has never been enough of anything to keep “everything going” as far as I know. My point was perhaps too simple: anyone will have enough of anything they desire if they can afford it. If oil goes to $200/bbl there will be an adequate supply to satisfy everyone that can afford to pay that price. Granted the only potential buyer at that price for the long term may be the DOD.