The ASPO plot

Posted by Heading Out on September 11, 2005 - 3:51pm

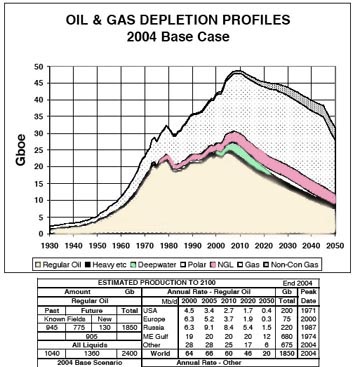

Sometimes it is useful to go back to the original source for the depletion curves that we discuss, and so I just copied this from the latest edition of the ASPO newsletter (which is a pdf from ASPO-Ireland which is on the Blogroll). To make it easier to read I have added a bit of color.

The relevant bits that I would draw attention to are the bulges up at the top of the curve, which relate to Deepwater production (green), and to the growth in supply of Natural Gas Liquids (pink).

If you look at the list of new projects that have been the subject of the posts last week, relative to CERA, you will see that a significant number are coming from Deepwater. These are the more expensive efforts that are long in planning, and which can more easily identified as a result. And note that it is these that are cummulatively now moving us upward, instead of already falling back. They are also "The Last Frontier."

Natural Gas Liquids, more commonly associated with gas production are also the major source of the additional oil that CERA is predicting will come to the global rescue. The volumes shown here do not seem to agree with CERA numbers, however, and so I suspect we will need to do a little more detective work to see where they all come from.

On the whole, oil is not used to get oil out of the ground. In 1997, roughly 90% of the fuel energy used by the oil and natural gas extraction energy was provided by natural gas (most of which was produced on site).

See ENERGY INTENSITY OF OIL AND GAS EXTRACTION

As for my comments on the graph

It's like someone claiming to have an undiscovered, authentic manuscript by Shakespeare, but not letting anyone see it. How much credence would you give to that claim?

I have read papers the ASPO people have presented in their seminars. I think those people are very serious. They know. Their main task has been to come forward with the phenomenon itself, the Peak Oil. They have also tried to make a very long range estimate of the production. This is of course virtually impossible...

There is also a political aspect in ASPO work. They changed their scenario last year and reduced the "swing" component of Middle East markedly. I think this was to emphasize the problem. Simmons has been still more pessimistic about the Middle East capacity. It should be remembered that here are people who consult the US goverment and big oil companies. The public domain scenario might not be the same they tell them.

But ASPO uses the Hubbert methodology. It is much more than extrapolating present production trends and summing new projects. M. King Hubbert could predict the US peak in 1970 already in the '50s and place the world peak around 2000 (conventional oil) in the '70s. This is astonishing. No economist can make very long range forecasts so accurately. It is difficult enough to guess the next year right. IEA has had difficulties in predicting the oil supply and demand one year ahead (can they get 6 monts right or the past 6 months production...). The greatest discrepancy between ASPO and the official forecasts (EIA,IEA USGS...) has been in the next 20 years or so. Here I would rely more on M. King Hubbert and ASPO than others.

If we look at conventional (and especially onshore) oil, Campbell hits fairly right. There were problems already in the end of '90s. This is not meaningless. Regular oil still makes the bulk af all oil production. The offshore production change rates are much higher and very high in deepwater. That's why we see optimism now.

I completely agree with you that they have been extremely brave at considerable personal career risk, and have done an enormous amount to draw attention to the problem. But that doesn't mean we shouldn't try to improve on their methodology. And the way any science advances is by open publication of results, sharing of data, critique of methods, leading to steady improvement. Since they haven't seen fit to share their database, that process is impeded, and I think Lynch is right to draw attention to that fact.

Refining is an entirely different factor. "Petroleum refining is the most energy-intensive manufacturing industry in the United States and accounts for about 7.5% of total U.S. energy consumption." I haven't done a refining calculation yet, but this link is one gateway to the data:

http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/mecs/iab98/petroleum/energy_use.html

The energy flow diagrams for the U.S. given on P. 2 and 3 of the following document are also good sources:

http://eed.llnl.gov/flow/pdf/ucrl-tr-129990-02.pdf

% of american energy produced spent on refining:

1985 6.56%

1988 7.62%

1991 6.81%

1994 7.02%

1998 7.50%

So, a trend with the exception of 1988?? And Im sure there is more recent data than 7 years ago? - but maybe not

This region is other people's hobby as well. Sir Mark Thatcher had much more profitable approach to Equitorial Guinea: just take it over.

I'm interested in the geopolitical aspects, reasoning that oil isn't of much use if you can't successfully extract and trade it. Info on your corner of the world:

Political Stability as a percentile of world,

World Bank average of 5 to 8 surveys

http://info.worldbank.org/governance/kkz2002/

Angola 18

Benin 35

Cameroon 21

Congo 9

Equitorial Guinea 37

Gabon 48

Nigeria 5

Togo 33

For comparison, Saudi is 31, Egypt 25. Using that sort of scaling, we can say there are no really stable counties here. And I'd bet, the better the oil, the stronger the urge to take it over.

The Angolans say that their total production will be double the present in 2008. It would mean 1.8 mpd or slightly more. This also ASPO peak rate for Angola. But the curve is very steep. ASPO curve shows that the production will collapse immedately after the peak and it will be back at the current level in 10 years. ASPO thinks that Angola don't want to develop the deepwater at the maximun pace. But they want. So ASPO puts the peak near 2020 but the Angolans say that level will be reached already in 2008. Because the conventional production will be higher then than 2020 this means that they will get real peak about 2010. Everything will be over in 25 years. After that the total production will remain quite small. Nice ride!

All this means that in 2012 - 2015 Angola may export almost double the present amount but only very short time. In five years it may be back at the present level. So this is a very short-lived affair. In fact it would be a quick robbery of Angolan oil and no lasting remedy for the US oil needs.

What do you think?

Since we are seeing these really sharp deepwater decline rates it might be a wild ride indeed.

HO

Meanwhile, there are entertaining analyses like Deciphering Russia's oil production from RIA Novosti.

Now RIA Novosti in fact tells that the production is flat this year. Because the production was still growing througout last year (9%, EIA), year-to-year comparisons give seemingly some growth this year, too. If we compare the month-to-month numbers the picture is different. Excluding some companies doesn't mean nothing. It is convenient to blame Yukos for the problems but we'll see only later if this really was temporary or not.

On todays (September 12) Newsweek there's an interview of the acting secretary-general of OPEC, Adnan Shihab-Eldin, on page 68. Here's an interesting quote from the interview:

"

Q: But won't the soaring demand from the developing world -as well as a forecast decline in supplies- inevitably keep prices high?

A: We wont't have a problem in 10, 15 or 20 years' time because the resources are sufficient and the investment is already in place. We don't see any problem in meeting demand from the developing countries even if demand continues at a robust [annual] level of 5 percent. Obviously in 40 or 50 years' time there may be [a problem], but we will have plenty of time to work out alternatives.

"

I don't know enough to think anything about this. What do you think?