A Megaproject list from the Oil and Gas Journal

Posted by Heading Out on June 18, 2006 - 10:22pm

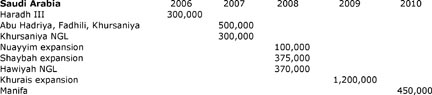

The projects are not all inclusive, at least I hope not, since they have only one new project for Russia, Prirazlomnoye in 2009+, and they do not give any oil production numbers for Sakhalin Island at all, but notice who the new player is (our good friend Gazprom, of course). But the OGJ also reaches deeper into the smaller projects, there being one down as small as 5,000 bd for example. To correct my comment the other day on where the Saudi oil will come from in this time frame they have:

This will cost somewhere on the thick end of $20 billion, but will very largely produce (other than the Manifa which is heavy) light and extra light oil.

The listing is also useful because it lists the NGL that can be expected from natural gas production, and where new natural gas production can be anticipated (and again there is nothing new from Russia until Sakhalin 1 comes on stream in 2009).

In regard to new technology they cite increased fracturing of wells in the Piceance basin where, with an average of 45 well fracture zones per well, ExxonMobil have developed a way of accelerating gas production from the wells by a factor of around 3-fold (1 bcf in 500 days as opposed to about 0.3 bcf). The technology won the Most Innovative Commercial Technology of the Year.

The summary comments deal more with the finding of new gas projects including the Great Gorgon in Australia (2 LNG trains), and an expansion of the LNG facility in East Timor. There will be a new LNG facility in Norway at Snohvit. In Kazakhstan they will reinject sour gas at Tengiz to increase oil recovery. There will be a new LNG facility off Equatorial Guinea, while there are three new LNG projects anticipated for Nigeria, although there is a question as to when they will come on line. And Peru is anticipating an LNG plant for their Camisea field.

If we are to put these projects in the same context as earlier discussions relative to the balance of supply and demand then if we are looking at an increase in demand of around 1.2 mbd/year globally, then we had better hope, either that depletion of production from existing wells is less than 4% or that folk keep cranking up that ethanol production (grin).

Interestingly our friends from CERA have just come out with a report that states that supplies will be tight now through 2007. After earlier claiming that it would not be long before we would be `swimming in oil" they now state that

Disruptions to supplies of gasoline, diesel fuel, and light products, associated in part with changes in fuel quality standards, will keep oil markets tight and prices high during the next 2 years, Cambridge Energy Research Associates forecast in a report issued June 6.They also see an increase in refining costs due to a shortage of skilled labor, and construction materials, while they expect midwestern and Middle Eastern refineries to start adapting more to dealing with heavier crudes."Incremental additions to refining capacity over the next 2 years [will] be insufficient to meet new global demand," it predicts.

I took the report from the paper version of the OGJ, which also has a section on the oil sands of Canada, and I will include a comment on that in my next post (grin).

Energy exploration 'hit by rising costs'

The biggest hold up for LNG projects may be price.

Everyone was licking their chops at the prospect of getting into the LNG game at prices of more than $12.00 or $14.00 dollars per MM/BTU, but the dew has gone off the daisy at prices down in the $6.00 range. This seems to cause some folks to notice what would seem to be a perfectly obvious condition of LNG: It always has to compete against local pipeline gas first.

This is why the contracts are long term term in the LNG trade, and why the investment can only be undertaken at the lowest possible assumed prices.

Once you begin building (actually before, if you include all the legalisms) you are married to whatever market price you assumed would be in play for many years out in front.

The same situation is true of huge pipeline projects, and is why there has been so much vacilation on the Alaska nat gas pipeline.

It's a tricky business. For LNG terminals and pipelines to make sense, the price has to stay high enough to pay for the venture to repay the investor but low enough not to destroy demand through "off shoring", conservation and alternatives.

The truth is, no one has any real idea how much natural gas we have. There is stranded gas, coalbed gas, tight gas, unconventional gas, offshore gas, and gas still under moratoria for environmental reasons.

There is the problem of weather. A few mild seasons in a row and the fact that North America may be peaked means little with the price collapses for a half decade or more and it's your money tied up in a furloghed LNG terminal.

There is the problem of regulation. What if the U.S. government simply threw open all moratoria areas? There is the problem of substitution by LPG or GTL.

But.....

The opposite edge of the sword is always worrying. After 4 or 5 easy winters, when nat gas stayed cheap, we could get hit with a back to back record winter, and consumption would skyrocket so fast that there would be no time to put in the LNG or the Alaska pipeline. It would be too late. And the United States and Canada could then face at least an economy threatening problem, at worst a life threatening one.

Darley can write. Simmons can write. Yergin can write. The EIA and IAE can write. The USGS can write. But the truth is, it's a crap shoot.

Roger Conner known to you as ThatsItImout

But if the US is to recieve 10%, or even 6% of it's domestic NG from LNG. a significant, and expensive, expansion of the world LNG fleet is needed. LNG tankers are several times more expensive per unit of energy than oil tankers (superinsulated containers with speciality steel and high quality construction).

When Spain was hit with a bad drought, they increased LNG imports on the spot market (which exists) and imported more from Algeria & Nigeria (I assume). Shipping was not a major issue, they had extra capacity at their recieving terminals. Italy et al made up for less LNG with more Russian gas and a profit.

If the US has a bad winter, a hot summer and then another bad winter, we will run into tanker shortages if we try to increase supply through the thin spot LNG market.

We may find LNG supplies, have enough capacity at LNG terminals but not have enough tankers to move very much LNG.

China will be buying Australian LNG. In an emergency, we buy a cargo from China, but it will take four times as long for the cargo to get here. Is China willing to delay three cargos worth "until the end of the contract" and resell one cargo to the US ?

IMO, the sudden demands of the US on the spot market will overwhelm spot shipping before we exhaust either spot LNG supplies or our limited recieving capacity. Shipping will be the critical bottleneck for the US due to our location.

One "competive" advantage of Gulf Coast LNG terminals is that we are closer to Africa than New England terminals, and Florida has trouble with putting LNG terminals anywhere.

BTW, are their any West Coast LNG plans permited yet ?

The Sempra terminal just south of the MExican border is under construction and has has for permits almost doubling capacity.

See this blog for the news:

http://calenergy.blogspot.com/

I generally keep an eye on these developments but I can't claim real expertise in the day-to-day.

"If the US has a bad winter, a hot summer and then another bad winter, we will run into tanker shortages if we try to increase supply through the thin spot LNG market."

Where are you seeing tanker shortages?

After reading a wall street journal article pointing to a glut of tanker ships, I have yet to see the tanker situation change. Every LNG production facility being built have corresponding tanker ship orders being placed. There are also some tanker operators who have order ships for the spot market. From all evidence available now, the tanker market is not the bottleneck, but the LNG exporters are the bottleneck. Delays in getting production to start and other production delays are really hurting the tanker operators.

I will say this: tanker builders need a long lag time between orders and delivery, so it is possible that LNG producers accelerate their production beyond tanker transportation capacity. Nevertheless, we are not seeing that now nor in the near future. You must be looking at the long term to state that LNG tankers are the bottlenecks.

You stated:

"China will be buying Australian LNG. In an emergency, we buy a cargo from China, but it will take four times as long for the cargo to get here. Is China willing to delay three cargos worth "until the end of the contract" and resell one cargo to the US ?"

This is assuming a lot or you got countries mixed up. The last I heard, China has not sign any major deals for LNG from Australia. You must be thinking of Japan who is the largest importer of Aussie LNG based on signed contract at the moment. I do believe China is a wild card, but as of now, China does not have the market conditions to pay for expensive LNG that US, Japan, and Europe are currently paying.

My review of the news that is available to me is much different than yours. My conclusion is that the bottleneck is with LNG production and the lack of natural gas at these sites. At least, this is the bottleneck for the next 3-4 years.

I've supposed that almost all LNG traded today is on fixed contract. There may be some on spot markets but the amount is small. Anyone have figures as to spot as percentage of total LNG trade?

Last winter, US LNG terminals ran at well below capacity even with $15/mmBTU prices at Henry Hub and the US still lost ship loads to other countries (Spain?) I read one story of a tanker from Trinidad being diverted from our Gulf Coast to Europe mid-voyage.

If demand is outstripping supply, I'd expect liquefaction plant developers to get full take-or-pay contracts with very little open to selling spot. Given the perishablity of a tanker load of LNG, transport routings are also closely calculated in development. Unlike oil, LNG depletes in transit as it boils off making travel time a critical economic factor.

You just have to hope that some government agency keeps track of LNG to get your stats.

To further boost my claims, LNG trains are coming online slowly and very costly. Getting welders have been very difficult and if anyone seen how LNG trains are put together, you will know how much pipes you need to put together.

I am curious to know where all the natural gas is coming from to fill up all these LNG trains under construction. If these LNG trains are not in full production, there are no way in hell we will have LNG tanker shortages. It is faster to built a tanker than a train. It is even harder to find enough gas to keep the train in full operations.

A gas pipeline loses pressure as the flow rate increases. In fact, the flow is trans-sonic. That means that to push gas through a long pipe, one has to start with a high pressure to get meaningful gas out the other end. The longer the pipe for a given flow rate, the higher the pressure and the thicker the steel.

To keep wall thickness within economic bounds, land pipelines use booster pumps along the line to make up the pressure drop and keep the gas flowing. Often a pipeline will be constructed and then uprated later with the addition of more booster pumping stations.

A 2,000 mile long pipeline without booster pumps would require extraordinary amounts of steel or else flow little gas. Alternately, building booster pumps 20,000 feet underwater (and maintaining them) is as of yet an unmet challenge.

Tom,

I think people here at TOD will accuse me of being technically optimistic to a fault (some would say a HUGE fault! :-), but I have to say, that yes, a Transatlantic pipeline is out of the debate. Stringing a cable from a spool on the back of an ocean liner is small game compared to the construction and repeating the repressuring of the pipeline at regular interval....it would require repeating stations with compressors and power sources sitting on the bottom of the deep oceans...technically, we're good, but we just ain't that damm good! (don't we wish though...)

What is interesting however is the variety of ideas that are in play to move natural gas....here's one that has actually been explored by the Defense Department as far back as the 1950's....

Suppose you built larger than Hindenburg size airships.....and fill the supporting bladder with natural gas.....it is lighter than air by enough to be bouyant, since it is mostly hydrogen....Then you simply tow a couple of the balloons with one powered airship.....with the weather satellites and good communication, you could steer above and around really rough weather (it would be at least as safe as a deep offshore oil rig in a hurricane!) and move the gas without liquification. :-)

The balloons would have to be VERY LARGE to move enough to make it worth it,but if the airship is well designed aerodynamically, for examle, as a "delta

type shape, they would be very stable.....

The Russians once had an even more radical approach....they were going to fill "floater" balloons with natural gas, and release them into the high altitude....then whenever winds carried them somewhere that had a market for gas, or close enough to it, the customer would send a plane up to capture and retrieve the balloons! With GPS and electronic I.D., the customer would then be billed for the balloon!

And people call me an optimist! :-)

Roger Conner known to you as ThatsItImout

Roger Conner

****************

That's thinking outside the box!

Just to try to think a bit outside the box, why not 'float' the cross ocean pipeline say about 30 to 50 meters below the surface. An electrical power cable running with the pipeline would power the booster pumps. All servicing would be at relatively easy to get at depths? Probably wouldn't take any more materials than building a bunch of tanker ships?

O.K., Jon, I hand over my optimists title belt to you, at least for now....:-), that's actually pretty good, in particular if the route was correctly chosen...(would a polar route make sense?)....interesting stuff! I am sure we could sign the Brits up for a station on the line! :-)

Roger Conner known to you as ThatsItImout

Would there be enough gas on either side to justify this?

I think if cost was not an issue then yes, technically, engineers will come up with a solution, but it will be damn expensive.

My understanding is that historically there was always a surplus supply ready to bring to market. Inexpensive field development allowed lots of supply to be on hand if needed. Now all new sources cost an arm and a leg to develop. No guarantee of ROI unless price stays high, so many aren't developed.

Doesn't this situation guarantee that prices will stay high going forward? As many people state the era of cheap energy is over.

Pretty good additions this year... are we awash in oil? Is depletion keeping pace? If depletion is increasing, won't at least 2007/8 get worse?

http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/bizchina/2006-06/16/content_618447.htm

---------------

Shenhua to build oil projects

By Wang Ying (China Daily)

Updated: 2006-06-16 08:57

China's biggest coal producer, Shenhua Group, plans to convert coal into 30 million tons of oil by the year 2020 in four northern provinces.

Three of eight projects planned will be completed by 2010, Zhang Yuzhuo, in charge of Shenhua's coal liquefaction business, told an energy forum hosted by the China Energy Research Society in Beijing yesterday.

The first three plants are expected to have a total capacity of 4 million tons a year, said Zhang.

"We aim to produce 30 million tons a year by 2020," the company executive said.

The eight plants will be built in Shaanxi, and the autonomous regions of Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang Uygur and Ningxia Hui.

The State-owned energy conglomerate plans to partner with foreign companies, such as Royal Dutch Shell and Sasol, based in South Africa, over technology transfers.

"We have almost finalized talks with South Africa and will possibly sign a deal with them sometime next week," Zhang said, declining to give details of the accord.

China's already burnt that same damm goal about 6 times in 6 different ways, haven't they?

It's a good thing that China's "plans" to burn coal don't create CO2 as fast as actually burning it....if so, London would no longer need it's "Tropical Wing" at the botanical gardens!

Roger Conner known to you as ThatsItImout

Don't know what the equivalent CO2 release rate is for GTL but I expect it would be less than for CTL since you're starting with excess protons on GTL and a deficit in CTL, supplied by H2O.

The carbon monoxide is burned again to make CO2 plus feed some heat back in.

Note I make no claims to expertise on this subject but I'm learning too.

Or do they mean that Haradh III will come on stream in 2006 and its maximum peak production is predicted to eventually reach 300,000 bpd ?

If its the latter, won't the field follow a Hubberts curve and reach a predicted 300,000 bpd several years (decades ?)after 2006.

When you say quite steep, any guesses how steep ?

Even 2 or 3 years to ramp up to peak flow, makes a big difference when considering the precarious supply/demand balance up to 2010.

I think they know what we know and have been trying to preach what they HOPE will happen and now realize that it WILL NOT SAVE them in time. So to stay on the side of Truth they give the MSM a bit of it and hope when the time comes to admit Peak Oil has been here all along they can point back to statements like these and mention that they had been trying to tell us all the while.

Or I might be up to early and need more sleep to form better opinions. Laughs. Okay best go back to bed anyway, I'll save energy when the computer is not on.

ExxonMobil's estimate for the world decline rate, before new production, was 4% to 6% per year, or about 4 mbpd of new production that we need to stay even. Assuming a steady state of 85 mbpd in total production, over the next 10 years we need about 40 mbpd of new production, or four new Saudi Arabias--just to stay even, without meeting any new demand.

Total Fossil Fuel + Nuclear Energy Consumption

At current rates of consumption, over the next 10 years we will consume--from fossil fuel + nuclear sources--the energy equivalent of about 730 Gb of oil.

I assume that you mean that this is an annual decline of 1.1 mbpd per year. This would equate to a percentage decline rate of about 1.3% per year or so. I again assume that you are talking about the decline rate in existing production.

To put this in perspective, consider the long term net decline rate for Texas--about 4.4% per year. Note that this is the net decline rate, after putting new oil wells on line.

Also consider Cantarell. Current production about 2 mbpd. Current oil column: about 825'. Thnning at: about 300' per year. Internal Pemex reports suggest decline rates (worst case, but reasonable considering the oil column): 40% per year. This is a worst case decline of 800,000 bpd per year.

Also consider the North Sea, which has dropped close to 25% since peaking at 52% of Qt in 1999. Again note that this is a net decline after adding new production. Based on the HL method, the world is approximately where the Lower 48 was at in 1970 and where the North Sea was at in 1999.

The total increase in world production, according to BP was 890 kbd. Does anybody know what the projections were for new projects coming online in 2005? Or how much acttually did come online? If so, subtract 890 kbp from that and you would have a figure for depletion and disruptions.

ALBUSKJELL: URR= 5.1 Gb, K= 8.4%STATFJORD: URR= 3.5 Gb, K= 25.8%

OSEBERG: URR= 2.1 Gb, K= 32%

TAMBAR: URR= 2.2 Gb, K= 32.7%

OSEBERG: URR= 2.1 Gb, K= 32%

COD: URR= 1.43 Gb, K= 37%

I don't know the exact cause.

More importantly, how many other Norwegian fields are there in addition to these that would make up, say, 95% of all Norwegian production? Do you have numbers for them?

The good news is that high prices will eventually bring texas advantages to the rest of the world, meaning the downslope should be a little gentler.

Keep in mind the image of a horizontal pipe and rising under it oil and under that water (or gas). At the point when the water (or gas) level gets to the horizontal pipe - it's time to blow taps for that field - or at least for that part of that field.

In any case, I assume that BP was certainly among the top 10 majors referenced by Matt. So, according to Matt Simmons, BP was assuring us in 1999 that the North Sea would not peak until 2010, while the HL method said that the North Sea was in peak territory.

BP is now assuring us that the world peak is decades away, while the HL method is again saying that we are in peak territory.

What was George Bush trying to say about fool me once, fool me twice. . .

The North Sea Oil Production Model

Through the 1980s and 1990s, oil production in the North Sea increased dramatically and some individuals and organizations were claiming that production would continue to increase well beyond 2000, or at worst decline only marginally. One organization providing fairly rosy assessments for future North Sea production was the U.S. Department of Energy/Energy Information Administration (U.S. DOE/EIA). For individuals looking closely at field production, it was obvious by the middle 1990s that oil production in the United Kingdom (U.K.) and Norway would achieve peak production around 2000 and then decline fairly rapidly.

Based upon U.S. DOE/EIA data, U.K. oil production (crude oil + condensate) achieved peak production in 1999 at 2.684 mb/d. The average production rate for the first 11 months of 2005 was 1.649 mb/d or 1.035 mb/d (38.6%) less than the 1999 average. Based upon data from the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD), Norwegian oil production (crude oil + condensate) peaked in 2000 at 3.291 mb/d. In 2005, Norway's oil production averaged 2.710 mb/d, a decline of 581,000 b/d (17.7%) since 2000. In 2005, 6 Norwegian fields declined by more than 20,000 b/d compared to 2004 (Table 1).

Field

Absolute Decline (b/d)

% Decline

Troll

60,994

19.92

Snorre

48,336

24.29

Draugen

30,844

22.91

Norne

30,011

24.84

Statfjord

24,257

20.19

Gullfaks

23,701

14.15

Table 1

The decline of Norway's large oil fields illustrates why Norwegian oil production is declining rapidly (8.4% in 2005 compared to 2004). The same process is happening in the U.K.

The U.S. DOE/EIA's International Energy Outlook 2001 (IEO2001), stated the following concerning future U.K. oil production:

"The United Kingdom is expected to produce about 3.1 million barrels/day by the middle of this decade (~2005), followed by a decline to 2.7 mb/d by 2020."

In the IEO2003, the U.S. DOE/EIA stated the following concerning Norwegian and North Sea oil production:

"The decline in North Sea production is slowed as a result of substantial improvement in field recovery rates. Production from Norway, Western Europe's largest producer, is expected to peak at about 3.4 million barrels per day in 2004 and then gradually decline to about 2.5 million barrels per day by the end of the forecast period with the maturing of some of its larger and older fields."

Note that these statements were made after production had peaked in both countries. The U.S. DOE/EIA includes liquified petroleum gas, refinery gain and other hydrocarbon liquids in their assessments but those components make up a relatively small part of oil production in Norway and the U.K. The statements above illustrate how poor the U.S. DOE/EIA long-term assessments can be.

This is important because I've been hearing comments from and seeing assessments by the U.S. DOE/EIA, other organizations and individuals which describe a big increase in global oil production in the next ~20 years, largely based upon big production increases in deepwater regions (>1000 ft water depth) of the world. In the next 4 years there will be a large number of deepwater oil projects coming on-line in the Gulf of Mexico (GOM), Campos Basin (Brazil) and off west Africa, regions where most of the deepwater oil will be found.

In the case of the U.S. GOM, 6 large fields with peak production >=100,000 b/d are expected to come on-line during 2004-2007 bringing ~850,000 b/d of summed peak production on-line. It's possible that U.S. oil production will increase over the next ~3 years due to the introduction of those fields, assuming no further hurricane problems. The down side of the rapid increase is that the increase will be followed by a rapid decrease, similar to what has happened in the U.K. and Norway. It appears to me that U.S. deepwater GOM oil production will peak in approximately 2010, as will Campos Basin production. Deepwater production off west Africa will peak somewhat later. Peak production in those areas will be followed by fairly rapid production declines. Recent assessments by the U.S. DOE/EIA don't account for rapid declines after peak production for deepwater regions so don't be surprised if their long-term projections are off dramatically.

http://policypete.com/Misc/TheNorthSeaModelofOilProduction.htm

Too bad we don't have a better "filing system" for collecting posts such as this...

Depending upon the day of the week, I believe that world Peak will be 2006, 2008 or 2010. With this datum, today I think Peak Oil will be 2010 !

http://www.energybulletin.net/17262.html

Not exactly what you're asking, but similar subject. Blanchard says he correctly called the North Sea peaks in '99 and '01, and is calling world peak in 2010.

Big oil projects and nuclear power plants draw on many of the same skill sets (welders, concrete workers, boilermakers, industrial electricians, etc) and same materials (rebar, concrete, steel pipe, copper wire).

We're looking at a 30 reactor expansion starting over the next 5 years in the US alone. That's about $100 billion worth of construction for a market that's put no demands on supplies for the last 30 years. Add in global demand easily double that and there will be crunches.

Good thing that China is putting a slowdown on construction and easy money

Now would be a good time to own a blast furnance or take up welding.

while i do know steel was made long before the industrial revolution, it was said revolution that allowed building grade steel to be made.

You can even use bio-coke (charcoal) as a substitute for coal.

There's a marketing idea - green steel!

Sent you an e-mail. I need a little information on what you've got in mind regarding OGJ and those tar sands.

get in touch, OK?

Thanks