Drilling Rigs and Drilling Ships

Posted by Heading Out on December 6, 2009 - 11:03am

The debate about how much oil is left and recoverable in the world has brought increasing attention to the recovery of oil and natural gas from offshore. And while I suspect that most of those who comment on this site are very familiar with all the terms, some of the more general readership may not be. Let me, therefore, explain just a bit about some of the different words that are being used here - with references and videos, where I can find them - to pictures of the different types of structures that are being used. And if I miss some, please chip in either to ask or answer. Previous posts in this series can be found at the tech talk link.

Just as on land, we need some form of drilling rig if we are going to drive a bit down through the rock and find us some oil. But, unless we are working somewhere like the North Slope where we can wait until the sea freezes over and drive ice roads out to build islands to drill from, we are going to have to find a different way of providing the infrastructure support for that bit. And here is the first distinction - because a drilling rig, in the offshore sense, is more of an exploratory tool, going out to find oil, rather that developing the known fields and bringing in production. That latter task is left more to production platforms, which can be sited where best to drain the field, and may not even use the initial holes drilled by the exploration rig.

As you may have read the Minerals Management Service keeps track of production offshore (as well as on Indian lands) and lest you think that it is not that significant a bunch of folks, they have just handed out $10.68 billion in 2009.

Of the $10.68 billion, $1.99 billion was disbursed directly to states and eligible political subdivisions such as counties and parishes. Another $5.74 billion was disbursed to the U.S. Treasury; $449 million was disbursed to 34 American Indian Tribes and 30,000 individual American Indian mineral owners; $1.45 billion was contributed to the Reclamation Fund for water projects; and $899 million went to the Land & Water Conservation Fund, along with $150 million to the Historic Preservation Fund.

As with many departments of the Administration the MMS is focusing on

the importance of renewable energy and job creation, climate impact and adaptation, and efforts to support and maintain the treasured landscapes of America in the emerging clean energy economy.

Since it also controls (for the Secretary of the Interior) lease sales – with a large upcoming one in the Gulf it is a good site to check on periodically. Now to get back to what we’re going to do to get the oil/gas out if we are fortunate enough to get one of those leases.

In really shallow water, or the bayous, you might launch your bit from a drilling barge, where the derrick can be assembled once the barge has been towed to the right place. Barges can be flooded to rest on the seabed in relatively shallow operations.

However they are very susceptible to bad weather, and last April one had to be raised after being sunk during Hurricane Gustav.

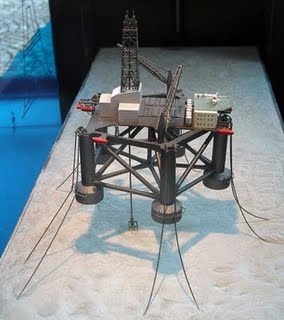

So, as one moves further offshore, then one might use a self-erecting tender from a barge, but would more likely move to something which could get the drilling floor stabilized and up above the waves. These are the jack-up rigs.

Typically they have three legs, that are raised as the rig moves around. Then when it has reached the desired site, the legs are lowered to rest on the sea floor and the entire structure jacks itself up out of the sea, and, hopefully, above the waves. (You can get a paper model to cut out and assemble for this rig). There is also an animated video showing the installation of a rig at a site.

They can do this to work in depths to around 500 ft. The discussion about damaged rigs gave links to the different rigs that have been damaged, and some of these have photos of the rigs in better days.

As one goes out to deeper depths, then one will look for a more substantial vessel and so one comes to the Semi-submersible.

These are built to either sail themselves, or to be towed out to the site, with the assembly floating, and then fluid is pumped into the bottom tanks to partially submerge the vessel and thus stabilize it. One can get some idea of the size of these from some of the photos shown where, (thanks to Ed Ames), wikipedia covers the subject.

Since these are floating there has to be a way of holding them in place. One way is to have them dynamically positioned, using thrusters to hold them in position, such as these.

Note that it takes about 3 years to build such a unit. The alternative is to have the rig attached to anchors on the sea bed using cables, or tethers. (And for those interested in natural gas production, note that the same rigs are used for both).

The connection between the well and the platform now becomes more flexible and special connecting pipes called risers are designed to reach from the blow-out preventer (BOP) at the top of the well, but on the seabed, and the platform. These must allow the rig to rise and fall with the tides and so models of behavior have to be written to design ways of allowing this.

An alternative is to use a drillship to do the exploration. The drillship has the rig mounted in the middle of the ship, and can thus move around somewhat more easily than the others. It is generally held in position by dynamic positioning while drilling. (Video here).

Once the field has been established, then a larger production platform can be brought out and placed where it can, using directional drilling, reach the best places to extract oil from the field. It is these large structures, such as that the Orlan platform from which Sakhalin Island oil finally began to flow recently, or the Thunder Horse, or Mars platforms. Although the former was due to produce by 2005, it was delayed by damage from Dennis and did not get up into major production until the end of last year, while the Mars platform was extensively damaged by Katrina. it is now back in production.

One of the problems with using these large platforms for Deepwater recovery is that they focus collection and so when these two are disabled, for example, they take about 400,000 bd out of production. And once they are damaged they are not so easily replaced. Back when I first wrote on this subject, in 2005 demand for rigs so strong that, as the International Herald Tribune reported

"If a customer comes today with an order, he'll have to wait until 2009 for delivery," Choo said in an interview last week. "That's how busy we are. If he's willing to pay more, he can get a rig by 2008 from our American shipyard."

By 2008 demand was such that prices had risen to half a billion dollars for a drill ship.

The original article noted that while it may only take 2 years to build a rig, the yard could only work on 8 at a time, and thus current deliveries were for 2009. The more recent story notes:

As a result, drilling costs for some of the newest deepwater rigs in the Gulf of Mexico — the nation’s top source of domestic oil and natural gas supplies — have reached about $600,000 a day, compared with $150,000 a day in 2002.

These record prices have spurred a new wave of drill-ship construction. This boom could lead to renewed offshore oil exploration that would eventually bring more supplies to the oil market, and push down prices.

Already, 16 new drill-ships are scheduled to be delivered to oil companies this year — more than double the number delivered over the last six years combined. In fact, 75 ultra-deepwater rigs should be delivered from 2008 to 2011, according to ODS-Petrodata, a firm that tracks drilling rigs.

The Chinese have also introduced a new design which is circular.

The Sevan Driller is the world’s first of its kind, with the most advanced deep-water drilling capabilities that allow it to drill wells of up to almost 13,500 metres (40,000 feet) in water depths of up to nearly 4,200 metres (12,500 feet) and an internal storage capacity of up to 150,000 barrels of oil.

The owner is Sevan Marine. The construction of this rig started at COSCO Nantong Shipyard in May 2007 and was relocated to COSCO’s Qidong Shipyard in April for derrick erection and final commissioning activities. The rig is due for delivery in the third quarter of this year and will be deployed by Petrobras in the Santos Basin, off the Brazilian coastline.

As of last week it was on its way to Brazil (which takes about 75 – 80 days) where it will drill in the Campos Basin in just over a mile of water.

Again this is a very, very brief and simplified look at some of the ways oil and gas can be produced from under the sea. It barely touches on some of the difficulties that are encountered, however. The sinking of the one barge shown at the top of the post could have been also repeated with pictures of other rigs in storms, and in battered condition.

Thanks, Heading Out!

I think these platforms are interesting. I did a post a couple of years ago on my visit to Shell's Brutus Platform in the Gulf of Mexico.

One of the issues with the platforms is that they seem to be built for longer life that the time needed to drill a particular spot. They can theoretically be moved to a new spot, after the oil in the old spot runs out, but the new spot much be at the right depth for the particular platform.

The problem is that most of the shallow places have been drilled. Now, all of the "action" is deeper.

Chevron has some new drillships that drill up to a total depth of 40,000 feet.

True Gail...a non-producing shelf platform was once considered a minimal asset 20 or 30 years ago. A good-sized industry developed for cutting the platforms legs and moving it to shallower water. But, as you point out, drilling on the shelf declined over time. For quit a while companies kept marginal and non-producing platforms in place. But the damages from recent hurricanes have significantly changed such policies. A typical shelf platform removal, including plugging the depleted wells, might cost $10 million. But knock that platform over and the costs can jump to $100 million. The huge insurance claims in the last several years have also changed the insurance game and not just from the premium perspective. Coverage limits have been greatly reduced. I can’t offer a number but there has been a huge uninsured liability developed in the GOM as a result.

Here's a real life example. In 1993 there was the deepest water (600’) fixed-leg platform in the western GOM for sale. There was about $30 million of production left to recover. But the cost estimate to remove this platform was over $30 million. There was only one lift vessel in the world that could pull this jacket out of the water. It was in Norway and would costs $5 million just to mobilize it to the GOM. Once here the day rate was $500,000. Thus no one made an offer. As we were evaluating the project the Feds changed the rules. Instead of completely removing the jacket we could just cut the top 100’ off and drop it into the water. This was fine with the state of Texas. The jacket had already established itself as an artificial reef and was considered an environment asset. The salvage estimate dropped to $5 million. Essentially a win-win for everyone. Another important aspect was this platform was also a tie-in location for the western most oil/NG pipeline in the GOM. Today this is an important hub for DW development going on in the western GOM even though the field production is gone.

The bust during the 80's led to many mobile drilling rigs being scraped. In some cases it was long overdue. We may be about to see another phase of rig salvage. The down turn has many rigs "stacked" in the GOM. Costs while stacked aren't great but it does add up. More importantly, the drilling companies look at the value from scraping a rig today vs. the revenue potential in the future. Obviously future utilization rates/daily rental fees play heavily in this analysis. If drilling stays suppressed we'll likely see scraping increase quickly. Thanks to Chindia activity there is a good market for scrap steel. Another factor in GOM rig count has been the flux due to our rigs being sent overseas. When local demand slips at the same time that overseas demand jumps there's a quick transfer. But not cheap. Typically these rigs have to be put on huge lift vessels to be moved overseas. Such an operation can cost over $30 million. Over the years many have been moved to the Persian Gulf.

Given the future limited shelf drilling this might not pose a big problem. We are seeing a minor up tick of very deep drilling projects in shallow waters in the GOM. The objectives are major NG targets. In January we'll participate in a 23,000' well drilling in less then 100' of water off the coast of La. About 12 months ago the drill hole cost of this well was $23 million. Now it's $12 million. Great for us but it indicates how much the oil patch service industries has taken a hit. The new deep play is exciting but will have relatively limited activity.

“Hopefully above waves” is call air gap. Legs are not very strong in the lateral direction so that wave forces must minimized on the hull.

The round circular discs at the bottom of the leg are called a spud cans. The spud can will bear against the floor and support the weight of the rig plus the weight on the string of pipe hanging off of the derrick. When the spud can sinks into the mud, the mud acts like a suction cup. In order to pull the leg out of the mud later if the rig is to be moved a spud can jetting system is used. The nozzles are placed around the cans. The nozzles are connected to a high-pressure pump that supplies water to the nozzles. The nozzles when pressurized blast the mud away from the spud can and so the leg can be retracted.

The jackup will have say (4) V-16 caterpillar generators that supply power to the motors on each leg that lift the platform. They are geared to the leg or have notches like a jack to move the leg down. As the rig is lifted out of the water, it is impossible to draw suction from the ocean to cool the diesels. A standpipe not shown runs down one leg and is pressurized by a submersible pump on the leg that pressurizes the standpipe. As the rig is lifted there are nozzles along the standpipe at different elevations that allow the operators to disconnect a hose and connect to another nozzle so cooling water is never interrupted as the rig is lifted.

Normally the rig before the lift is pre-loaded with water. All of the ballast tanks on the rig is filled with water. The purpose of the pre-load is ensure that the legs are sunk deep enough into the mud to hit a solid base on the floor. If the legs are not solid on the floor, one leg could buckle and the whole think would fall into the drink.

The floater, as they are called in the picture, is a TLP. Thunderhorse a TLP weighs about 30000 tons. Spars are another type that is a long cylinder that extends into the water with the topside mounted on the top of the can. Medussa the spar I helped design weighs about 7000 tons. One thing that was not covered is umbilical. The umbilical a cable that encapsulates many tubes, wires, and fiber. The purpose of the umbilical is to carry messages and power to the equipment on the floor. Another purpose is to send chemicals to the well head to inject into the well. Sometimes diesel is carried to the well to thin the oil. The diesel is recovered on the platform for reuse. The umbilical is the nerve from the rig to the equipment on the floor. One of the innovations lately to cut costs is to locate the production equipment on the floor. There may be numerous umbilicals that connect say (3) or (4) platforms to the mother platform.

I never knew the thrusters were used to stabilize the rig. They can be used to propel the rig from one location to another. When I worked offshore I have witnessed the strange creatures propelling themselves across the ocean. The thrusters I’m familiar with used variable pitch propellers but I guess today high pressure pumps have replaced the propeller. It certainly is simpler.

Another thing that is interesting is how the anchor chain is tied to the ocean floor. Sometimes they use cans that are pushed into the mud and then a suction is drawn on the can that imbeds it into the mud. Sometimes piers are used. The winches topside keep a pre-determined load on the chain to keep the rig on location. The riser that connects the BOP to the rig is very sensitive to lateral loads. There are different types of risers some connect the piping from the wellhead to the rig and the riser that connects the BOP to the rig. The BOP riser conducts the mud and fines from the bore back to the platform for reuse. The mud is very heavy and is also used to prevent blowouts.

I sailed on the Glomar Java Sea and Glomar Conception. The Java Sea sank but there are still many old rigs drilling. They use heavy anchors tied to chain that is attached to winches on board. The anchors are carried out about a quarter of a mile by work boats and then lowered to the bottom. It is very complicated system that keeps the chain at a pre-determined tension. Normally there well be (4) chains forward and (4) chains aft. Again it is very important to keep lateral loads off of the riser.

Mars is fixed platform whereas Thunderhorse is a floater TLP or Tension Leg Platform.

Chevrons TLP Typhoon sank with Katrina. Spars are very stable because the can is ballasted very low in the water.

Thanks for the details - these are amazing structures. One poster or the like I came across a while ago showed jackups in relation to the largest skyscrapers.

Now, how does this Sevan Driller thing work?

Seems like it shouldn't, but then I'm still scratching my head at spars. It'd be like stabilizing an empty water bottle in your bathtub!

Morgan Downey relates how the term "semi-submersible" was coined by Shell engineer Bruce Collipp, or rather the local Coast Guard official to whom he was explaining the concept to.

fascinating article and comments

this modern deep sea rig technology has got to be some of the largest, most complex and most expensive technology ever designed and used in any project

the economic break even for deep sea oil keeps moving out, and at some point it has to stop. where i don't know.

but this is some expensive oil

This is an image from a Shell website, showing dates of rigs and different depths:

Shell has some pictures of its new Perdido "spar" here and here.

According to Shell's website:

Production is planned for 2010 using the Perdido spar.

Wiki has a List of tallest structures in the world. Perdido, Bullwinkle, and Petronius all rub elbows with a raft of guyed masts and the Burj Dubai.

I see the Saudis were considering building a Mile-High Tower in Jeddah. Apparently the soil isn't quite firm enough to support such a monstrosity so it's been scaled back to "only" 1100m/3608 ft. Feh. How trivial!

Spars are transported to location in two pieces. One piece is the can and the second piece is the topside. Medussa had (3) decks maybe (4). I’ve slept since then. The can is floated to location like a bottle on its side. At location, the ballast tanks are flooded that are located at end that will be under water. As the tanks are flooded the can tips up vertical and sinks with a small part of the can exposed above the ocean surface. Heavy lift cranes lift the entire topside and stack it on the top of the expose part of the can. Medussa has (4) chains and winches that tie back to the mud cans on the floor. This keeps the rig on location. Medussa is a dry tree rig which means the trees are on deck. The risers from the wells come up through the inside of the can and tie to the trees. Many rigs though have wet trees which means they are located on the floor.

You can see the way they tip the can at location that there is a large amount of ballast located very low in the structure. This gives it a terrific amount of stability. Also, the weight of the topside acts along the centerline of the can so that it would be almost impossible to capsize the rig because the heeling moment never overtakes the buoyancy moment. The chains also add stability.

I talked to a man who worked on this spar and he said the motion on deck resembled a figure eight.

At the time Medussa was completed she was the Mother of all Spars.

Frontrunner is the sister to Medussa. Devilstower no relation to Medussa was the deepest of the deep water spars.

Semi-submersibles which I am not that familiar with are not used in deep water. The legs of the semi are flooded with ballast and sink down into the ocean. I believe they have thrusters to stay on location. Semi’s are not tied back to mud cans. TLP’s are tied back to mud cans thus tension leg.

Semi-submersibles are/have been used in deep water. One co. I worked for in the past had at that time,the record for deepest anchor set in the GOM (over 6000 ft. for Exxon I believe). Now ultra-deep may be another story. Semis can also be kept on location with DP (thrusters) or moored to the bottom w/any number of types of anchors, including the "suction pile" type.

Thanks gentle folk for all the additional info. There are lots of fascinating stories from the GOM and the rigs out there, but there is little that tells as much as personal experience.

And thanks Gail, for catching the info on Perdido, the scale of the challenges and the answers just keeps growing.

HO comment about personal experiences reminded me of a small nightmare a lifelong friend of mine, Mike, experienced about 8 years or so ago. It was a DW GOM well that had already been drilled and suspended as a subsea completion. A SS completion isn't tied to a surface structure. The wellhead sits on the sea floor and is connected by control lines/pipelines to a distant production structure. They had to latch onto this subsea well head to effect the completion. There is often a deep current (the LOOP current) in the GOM that has to be dealt with. The rigs are designed to deal with the max velocity (3 mph???) of the LC. Unfortunately they encountered a LC moving much faster then had been recorded before. Mike would watch the pilots in the control room try so steer the riser pipe, via cameras, to latch on to the wellhead. And miss and miss and miss. For about 10 weeks they just kept missing. I don’t recall the exact day rate but it probably as at least $400,000/day. Needless to say there was a bit of a cost over run before ops even started. Mike was working as a well site geologist as I had been for years. Great duty for Mike: eat, sleep and read for 10 weeks and get paid.

The really sad part of the story was that Mike and his wife were to two Americans killed on the Air France flight that went down in the Atlantic last spring. A great guy that was liked by everyone, without exception, that got to know him. Like me he had worked more than 30 years in the GOM and we had our fair share of near misses. Mike was working DW Brazil for Devon at the time. Then he doesn’t survive a vacation flight. Just another lesson about appreciating every day.

This is expensive technology required to get the "last" of the big oil for the US. Very good info that explains why much of the new oil requires $50 to $80 bbl price to produce.

I have one question: What happens when a gas well suffers blow out on a semi-submersible, does the platform sink due to drop in density of seawater?

That's exactly what happens mb. About 34 years ago when I had just started at Mobil Oil they had NG leak up around the surface casing of a well off the La. coast. The crew saw the gas bubbles but just sat and waited. In a few hours the water column density decreased and the rig quickly sank. All the hands made it off OK. Next time this happened they knew what to do: they cut loose the anchor system and had the field work boat tow them off location. Accidents still happen but the drilling companies now have a much better idea of the dynamics involved in such operations. In the bad old days loosing rigs and hands was considered just the price for doing business. Now safety training is a very big part of the process.

I now start to understand why it takes 10 years plus to go from discovery to production.

For example, could someone draw the timeline from when Brazil Tupi was a twinkle in someones eye - when they first got the idea that there may be oil out there and they should do some serious investigation - to today - to the estimated first production of commercial oil.

I would guess 20 years

How do you forecast costs and prices over 20 years? How do you plan for this, given rapid day to day volatility?

We make predictions for fun, but these guys have to back it up with real money

I know the cathedrals in medeval Europe would take a hundred years to build. So in some sense we are back to that. This is faith based management. You just go forward and assume that it builds day to day and eventually it will succeed.

It has to be "sunk cost" financing,(no pun intended) where you invest without a payback horizon, because NPV does not work. Hence government money is essential.

I compare this to the English channel tunnel, or the US moon shot, where there is assumed to be some ultimate public good which cannot be measured in dollars.

Poly -- As to "How do you forecast costs and prices over 20 years?" the answer is simple: you can't. Which doesn't mean they don't do just that. But in the end it's the current price of oil/NG that drives these investments. I know it sounds stupid but this is what I've observed for over 30 years: it's never easier to talk someone into an oil/NG project then when prices are high. But when you look at the history high prices are always followed by a price crash. Thus if you're dealing with a long term investment it's more likely you'll have low prices by the time you start production. Even short term investments can fail. Look back to the late 70's as an example: 4600 drilling rigs running in the US. Billions of dollars thrown at poor drilling projects because the embargo hype was out of control. I actually heard one shareholder in my then company proclaim (in 1980) that he was selling his stock because my management was only projecting $75 oil by the mid 80's but he had read in the Wall Street Journal that oil would be $100/bbl by then. In 1986 oil fell to around $10/bbl.

Today is a great time to drill in the US: costs are way down and there are numerous drilling projects begging for investors. But don't try to start an oil/NG investment conversation with most funds or bankers. But when oil was heading over $100/bbl last year these folks couldn't write checks fast enough. Now they have broken backs and fear such investments. From my experiences this is how it has always been and will likely remain the same. Fortunately for my company we are the proverbial fox in the chicken coop right now. Again, the simplistic rule still holds true: buy low...sell high.

Rockman - thanks

"buy low and sell high" and I guess you can add

... and be patient

one thing you can be sure of is: extreme price volatility will continue

For sure Poly. When I started in the 1975 the cycles seem to last the better part of 10 years or longer. Now look at the cycles we went thru in just the last 3 years. The next boom will take a while...probably 4 or 5 years IMHO. The bust can happen in less then a year as we just witnessed. My owner's model is that we'll peak again in that 5 year time frame. Then we sell out and head to the house before it all collapses again. Sure do hope he's right.