South America Enters the LNG World

Posted by nate hagens on December 3, 2010 - 10:34am

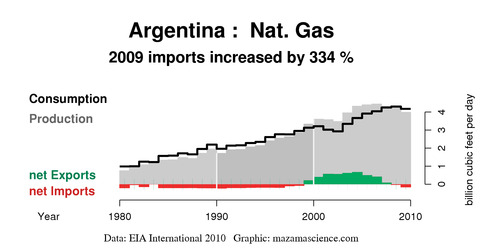

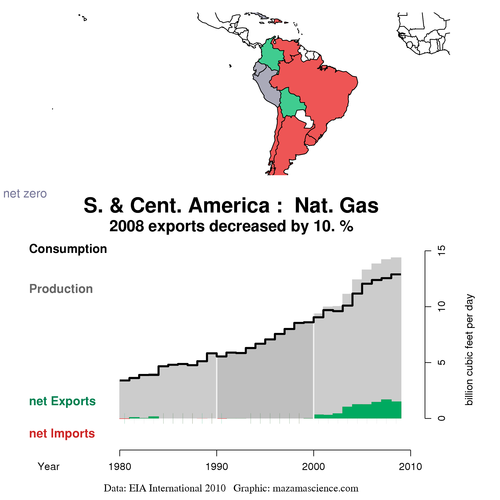

South America is about to change from a region of natural gas self-sufficiency to a source of demand for liquified natural gas (LNG) imports. A peak in production in long-time producer Argentina (Figure 4) has caused natural gas shortages in the Southern Cone while political issues are affecting exploration and development in Bolivia and Venezuela, the two nations with the largest gas reserves. A recently inaugurated liquefaction plant in Peru will enhance exports of LNG from Peru but existing and planned LNG regasification terminals in Argentina, Brazil and Chile will result in increased imports into the dominant economies. The region is on track to become a significant net importer of natural gas over the next decade.

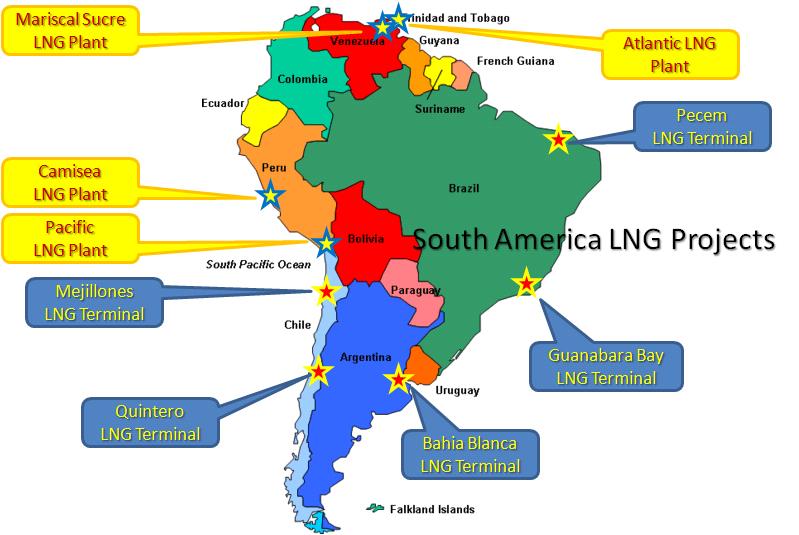

South America’s LNG terminals

South America is relatively new to the LNG market. The following map from lngpedia.com shows the location of all current and planned liquefaction plants (export) and regasification terminals (import).

Specifics for each plant or terminal are summarized in the tables below. (“MMtpa” = million metric tons per annum, “Bcf/d” = billion cubic feet per day)

Liquefaction Plants — Exports |

|||

| name | gas provider | capacity | status |

| Atlantic LNG #1-4 | Trinidad and Tobago | 14.8 MMtpa (1.89 Bcf/d) | inaugurated 1999-2006 |

| Pampa Melchorita (Camisea) | Peru | 4.4 MMtpa (0.56 Bcf/d) | inaugurated 2010 |

| Gran Mariscal #1 | Venezuela | 4.7 MMtpa (0.60 Bcf/d) | planned for 2013 |

| Gran Mariscal #2 | Venezuela | 4.7 MMtpa (0.60 Bcf/d) | no satisfactory bids |

| Gran Mariscal #3 | Venezuela | – | idea |

| Pacific LNG | Bolivia | — | idea |

Regasification Terminals — Imports |

|||

| name | location | capacity | status |

| Bahia Blanca | Argentina | 2.3 MMtpa (0.3 Bcf/d) |

inaugurated 2008 |

| Pecem | Brazil | 2.0 MMtpa (0.25 Bcf/d) |

inaugurated 2008 |

| Guanabara Bay | Brazil | 3.9 MMtpa (0.49 Bcf/d) |

inaugurated 2009 |

| Quintero | Chile | 2.5 MMtpa (0.3 Bcf/d) |

inaugurated 2009 |

| Mejillones | Chile | 4.4 MMtpa (0.6 Bcf/d) |

inaugurated 2010 |

| GNL Del Plata | Uruguay | — | contract awarded 2010 |

Summing up the capacity numbers in each table gives exports of 19.2 MMtpa and imports of 15.1 MMtpa. For the entire region, including Trinidad and Tobago, exports exceed imports by only 4.1 MMtpa. Excluding Trinidad, the South American mainland is already a significant LNG importer at 10.7 MMtpa.

A closer look at the nations involved will give some perspective to help understand how the South American LNG picture is likely to evolve in the future.

Trinidad

Trinidad (population 1.3 million) lies only 10 miles off the coast of Venezuela near the Orinoco delta and near the site of Venezuela’s planned Gran Mariscal LNG facilities. While natural gas has long been an important energy source on the island, the development of LNG export facilities beginning in 1999 have turned it into a globally important LNG provider (#6 according to BP Stat. Review 2010). Export volumes are limited by the four existing LNG trains which have been functioning near capacity since 2007. There have been discussions on constructing a fifth and sixth train but there are no definite plans as yet.

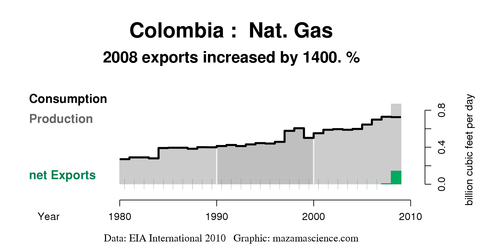

Colombia & Venezuela – reinjection and planned exports

According to the US Energy Information Administration country analysis briefs, most of the natural gas produced in these nations is used in support of the oil industry.

Colombia:

A large portion of the country’s gross natural gas production (43 percent in 2008) is re-injected to aid in enhanced oil recovery.

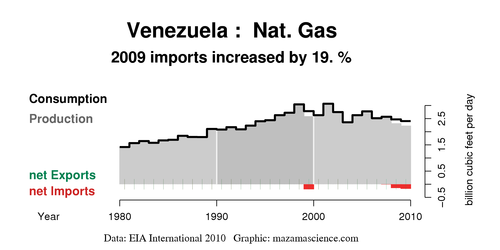

Venezuela:

According to Enagas, the principal government agency charged with regulating the natural gas sector, the petroleum industry consumes over 70 percent of Venezuela’s natural gas production, with the largest share of that consumption in the form of re-injection to aid crude oil extraction.

With global oil prices significantly higher than global LNG prices, it is likely the petroleum industry will continue to consume a large portion of natural gas production. Given Venezuela’s proven reserves (EIA) of 176 trillion cubic ft, however, it is no surprise that it would like to mimic Trinidad and Tobago’s LNG export example. Several LNG trains have been suggested but the first is still only in the planning phase.

A side-by-side view of production in Colombia and Venezuela (note the different scales) shows that Colombia’s production is ramping up while Venezuela’s has had difficulties, largely politically induced, since 1999. Given Venezuela’s current difficulties in the oil and gas sector along with an entrenched energy crisis, it is difficult to imagine that their various gas export pipeline and LNG projects[1] will be finished on schedule. It remains to be seen whether they can achieve first exports of LNG in 2013 as currently planned.

Peak Exports in Argentina and the Chilean energy crisis

Until recently, Argentina had been South America’s leader in natural gas exploration and production, rapidly passing Venezuela in gross production in the mid 1990′s. Despite rising consumption during the 1990′s boom times, Argentina was soon in a position to export natural gas to its neighbors. The GasAndes pipeline was brought online in 1997[1] with promises of providing Chile with a new era of clean, reliable energy. Unfortunately, it took only a decade before Argentina’s production growth stalled, due to a combination of geologic, political and economic factors, and was soon outpaced by demand. In 2007, Argentina signed with Excelerate Energy to build the Bahia Blanca LNG receiving facility which came online only one year later in June, 2008, just in time for the South American winter.

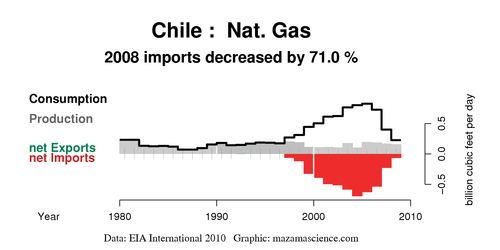

Chile was quite pleased as the first pipelines from Argentina allowed it to switch from expensive and dirty diesel to clean burning natural gas for thermal power generation. Chilean imports of gas increased dramatically from 1999 to 2004 to the point where it relied on piped gas from Argentina for 90% of its supply. Then, between 2004 and 2007, Argentina moved to conserve indigenous supplies of natural gas and increased export taxes and restricted supplies to its Andean neighbor. Chile was caught short[4,5] and quickly signed agreements to develop LNG import facilities, opening the Quintero and Mejillones terminals in 2009 and 2010, respectively. Beginning in 2010, we should expect Chilean consumption of gas to begin climbing again to and then past the levels of 2005. (Chile’s only indigenous supply of energy comes from hydro-power which supplies 20% of total demand.)

Brazil’s growing demand for energy

Brazil’s consumption of energy is rising steadily in sync with its growing population and booming economy. Figure 6 plots energy use from five main sources (excluding biofuels) and shows Brazil’s heavy dependence on oil and hydropower which together constitute 85% of the energy mix. (Biofuels supply less than 5%.)

.png

)

(Biofuels not included.)

Natural gas consumption, though small percentage wise, is rising steeply and Brazil has become a significant importer of gas from Bolivia through the GASBOL[1] and Gasduc III[1,6] pipelines. Imports did decrease in 2009, possibly due to increased hydroelectric output in that year, but the overall trend in recent years is steadily upward. The Mexilhão gas project in the Santos Basin [8] may increase domestic production by up to 0.5 Bcf/d starting in 2011 which would be a tremendous help. And there are high hopes for associated gas in Brazil’s ‘sub-salt’ oil finds but bringing that gas ashore is still years away. In the mean time, it seems clear that Brazil can and will increase its consumption of natural gas as needed to support its economic growth.

Bolivia

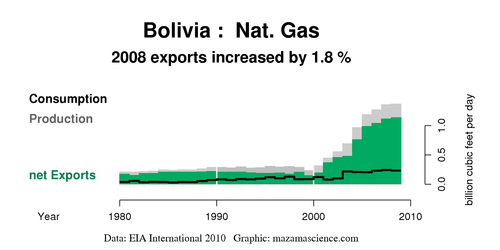

A word must be said about impoverished and landlocked Bolivia, once expected to be a major gas exporter within South America. Pipeline projects between Bolivia and Brazil[1,6] and Bolivia and Argentina[1,3] deliver natural gas to the continent’s largest economies and can be seen in Bolivia’s export profile in Figure 8):

This recent increase in exports is unlikely to continue in the immediate future, however. Bolivian resource nationalism, combined with the drive for energy security on the part of energy importers has pushed the recipients of Bolivian natural gas to embrace the global LNG market instead of relying solely on piped in gas from a single supplier. The situation is well covered in a recent New York Times article[7]:

The new gas-import ventures in Brazil and Argentina, as well as two in Chile, once a potential market for Bolivian gas, all use ship-borne imports, in which the fuel is cooled into liquefied natural gas for transport from exporting countries and reheated on delivery. This increasingly common transport method has provided substantial competition with pipelines in some markets.

…

“A decade ago Bolivia was preparing to be the energy nerve center of South America,” said Gonzalo Chávez, an economist at this city’s Catholic University. “Now a loop of energy-security projects is going up around us.”

Summary

South America’s most dynamic and open economies have embraced shipborne LNG as an important component of their energy mix. Five regasification terminals have opened in the last three years with expectations for increased demand in booming Brazil, peaking Argentina and energy hungry Chile.

On the other side of the coin, the nations with the largest reserves of natural gas and the greatest potential for increased exports, Bolivia and Venezuela, are also the least open to global capital markets and hence the least likely to see quick construction of LNG liquefaction plants. (Bolivia would also need to gain access to a coast.) At the moment, it is Trinidad’s contribution that keeps the continent in net exporter status. While Trinidad may increase exports somewhat with construction of one or two additional LNG trains, at that point it will likely have reached maximum capacity.

Barring a miraculous conversion of Venezuela or Bolivia into a paragon of Western style free-market capitalism, it seems that South America as a whole is destined to become an increasingly important importer of liquified natural gas in the global marketplace.

South America has likely arrived at Peak Gas Exports:

References

Articles

- South America snapshot (Pipelines International – Sep. 2009)

- As temperatures in Argentina get colder than Antarctica, energy demand rises (Washington Post – Aug. 3, 2010)

- Argentina Inks Deal to Build Gas Pipeline From Bolivia to Salta (Rigzone – Aug. 10, 2010)

- Chile’s Energy Crisis: No Magical Solution (Latin Bus. Chronicle – Oct. 22, 2007)

- Chile: Facing a Severe Energy Crisis (Roubini Global Economics – Feb. 12, 2008)

- Petrobras inaugurates Cabiúnas-Reduc III (Gasduc III) gas pipeline (Scandinavian Oil-Gas Magazine – Feb 4, 2010)

- Neighbors Challenge Energy Aims in Bolivia (New York Times – Jan. 09, 2010)

- Petrobras eyes Mexilhão start (Upstream – Oct. 06, 2010)

Papers

- Natural Gas Pipelines in the Southern Cone (PESD – May, 2004)

Links

- World’s LNG liquefaction plants and regasification terminals (globallnginfo.com – July, 2010)

Re: Petrobras eyes Mexihão start

As a native Brazilian this typo rubs me the wrong way a bit, it almost sounds like the Brazilian slang word for "Big Mexican", which would be Mexicão

The correct spelling should be Mexilhão which is the Portuguese word for mussel.

They named a gas field after a blue bivalve? In the North Sea, Shell named all their fields after sea birds which was also unusual. Brent being the Brent Goose.

On a more serious note, thanks for the interesting post Jon. Surprising in a way that S America got so little nat gas. Would be interesting to see your last chart with Trinidad deducted. And to see S American gas compared with the North.

Euan,

As Trinidad is the only country that had any LNG import or export capacity prior to 2009, the net export total for S. America will equal the production total. Just imagine away any gray outside the black consumption line and get rid of the green exports bit.

For a comparison with the North, you can see how S. & Central American natural gas trends compares with US consumption in the following image:

I think it's important to remember that South America as a whole hasn't developed their natural gas reserves to anywhere near the same extent as North Americans have. There are huge, largely untapped reserves in Venezuela and Bolivia with additional supply in Peru and perhaps Brazil. Even Argentina has more supply that could be brought on line with the right financial incentives.

Until very recently, natural gas markets in South America were limited by pipeline infrastructure. The continent didn't use much natural gas because they couldn't get supply to where it was needed. So the entire continent uses much less gas per capita and in toto when compared to North America or Europe. But I believe it's the trend that is important. South American nations, like nations everywhere on the planet, are looking to natural gas and especially LNG delivered from a world market to help solve their future energy problems.

Peak gas production or global recession?

N America blessed with more gas or is the S doing something wrong? (if anyone wants to normalise this for continent area - be my guest.)

Ignoring for the moment the question about whether N. Amer. is blessed with more, the charts and figures cause me to wonder:

I have read that NG fall off (rate of depletion) post peak is quite extreme, as compared with Oil, post peak. It looks as though S.A. is beginning that sort of drop. And so I wonder, is the depletion rate for N.A. going to be worse because of the frac-ing induced production increases. And, back to the first question that I deferred, may we expect an increase in S.A. production - are they heavily into hydro-fracturing now, and if not shouldn't we expect that they would be later?

Craig

Euan - Unfortunately I can't normalize. But anecdotally I've seen a number of proposed S.A. projects over the years and often the hang up wasn't the geology. It was above ground factors: lack of pipeline infrastructure (along with very high expansion costs) and a lack of storage causing production curtailment. Then add the negative effects on expansion from nationalization. S.A. may have significant NG potential that can't be exploited as readily as has been done in the USA.

Jon, you make some important points, and this is relevant to the S American and global energy debates. Intensity of FF development that is linked to the intensity of economic development.

But it's interesting that S American countries see more economic sense in importing LNG than developing indigenous supplies. This degrades their trade balance and currencies, exposes them to energy insecurity, and exports jobs. Where is The World Bank, the OECD and the IMF? What are they thinking about?

So Venezuela has 22.3 times the population of Trinidad & Tobago, and 192.2 times the area, and they produce less gas? That Dutch Disease is one nasty bug.

Jonathan - the image you linked to is a no go.

Here's what I was trying to post but I had a typo in the URL and now can't change it:

Same idea as in Euan's plots.

Sorry about that. Those typos are hard to catch when it's not your native tongue. And I'm sure that Petrobras doesn't want any "Big Mexicans" telling them how to run their off-shore oil and gas fields. ;-D

@Jonathan

Interesting overview of South American natural gas. I think the main issues of discussion in this are

1) The potential of Natural gas discoveries of the coast of Bazil in the pre/subsalt in the long term (2015+). Petrobras now considering the strategy of natural gas exports in the long term.

2) The development of Bolivian natural gas, both production wise and consumption wise.

Repsol in 2009 stated that it would invest 1.5 billion dollars to increase Bolivian production

"Reuters quoted him as saying the investment will allow the company to increase output in its Huacaya and Margarita fields to 8 million cubic metres per day in 2012 from the current 2 MMcmd, and to 14 MMcmd by mid-2013."

http://www.upstreamonline.com/live/article199909.ece

In respect to consumption, an interesting paper was recently published discussing Gas-to-Liquids plans in Boliva.

Jorge A. Velasco et al., 2010. Gas to Liquids: A technology for natural gas industrialization in Bolivia, Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering, 2, p. 222-228.

The article describes the following plans which would consume

"Expected Bolivian natural gas production during subsequent years also considers industrialization projects in the coun

According to YPFB, the startup of an ammoniaeurea plant expected in 2013. It will be located in Carrasco, Cochabamba, a

have a capacity of 600,000 tons per year of ammonia, a 720,000 tons per year of urea, using around 2.0 MMcmd of natu

gas. The startup of a GTL plant is projected for 2015. It will have a capacity of 15,000 bpd, and for 2021, another with simimilar capacity is projected. Each plant will have a natural gas consumption of about 4.5 MMcmd. These two plants will be located in southern part of the country (Bolivian Gran Chaco) near the mportant gas fields: Margarita, San Alberto, and Sábalo (each with natural gas reserves ofmore than 10 TCF). There are also other projects such as steel production (in Puerto Suarez, Santa Cruz de la Sierra) which will consume between 2.7 and 8.4 MMcmd of natu

gas (Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales Bolivianos (YPFB), 2009)."

Depending on how both sides work out Bolivia will either increase its exports, or exports would remain fairly stable.

Rembrandt

I wonder if ammonia exports should be considered an energy product (like refinery output), and included in this kind of analysis?

Excellent point Nick.

According to this page:

More detailed data is available from the International Fertilizer Industry Association (IFA)"

I don't think so. Ammonia is a commodity product that is produced using energy, just like petrochemicals, plastic, steel, cement powder etc etc.] (even lumber!)

While it is possible to use ammonia as a fuel, it is not used for this purpose anywhere in the world, and there is no infrastructure for this purpose, and producing more of it does not mean more energy is available to do work, it actually means the reverse. So to class it as an energy product is misleading - it should be grouped in with other non-energy physical commodities, as listed above.

Now, when that ammonia is used to fertilise an energy crop, like corn, then it certainly should be counted as an energy input, and even the US Dept of Ag does so for their EROEI calculations.

A product like methanol, presently, falls into the same category, as with the exception of China, no one else is using it for energy, just as an industrial chemical, though hopefully this will change, as it is a great fuel.

I'm not thinking of ammonia as a fuel. I'm thinking of it as something that would illuminate energy trade analysis.

Think of it this way: if Saudi Arabia decides to divert some of it's domestic natural gas production to ammonia, it reduces it's NG exports, but increases it's ammonia production. Assuming world consumption is constant, somebody else reduces their NG imports, and someone reduces their ammonia production.

An analysis that looks only at net NG exports would think that there was a growing problem with declining net NG exports, while an analysis that included ammonia would not. The same thing applies to oil and products like petrochemicals; electricity and aluminium production; etc.

Well, sure, what you are talking about then is the embodied energy in all exported (or imported) goods, from any country.

But to assume world ammonia consumption is constant is not a good assumption - I think you'll find if a country starts producing it, they will use more of it (except say Trinidad which has hardly any farmland). That aside, a country that starts exporting ammonia - and has no other energy exports or imports, would suddenly appear as a net energy exporter, when it ain't so - they are a product exporter, and are no in the energy business.

But, if you included it in energy trade, at what point in the ammonia chain do you then exclude it? When it is made into urea/nitrate? What happens when the ammonia is applied directly as fertiliser? You run into a problem of where to draw the boundaries, and the logical one is where it changes from an energy product to something else, as it can no longer be used as energy.

what you are talking about then is the embodied energy in all exported (or imported) goods, from any country.

Yes.

a country that starts exporting ammonia - and has no other energy exports or imports, would suddenly appear as a net energy exporter, when it ain't so - they are a product exporter, and are no in the energy business.

Yes, that would confuse your audience if you didn't clearly explain the purpose and nature of the analysis.

at what point in the ammonia chain do you then exclude it?

At the point where the gathering and analysis of data becomes too difficult. As long as the data is available, is clean, and one has the time to analyze it, the more the merrier!

As a practical matter, I'd include big, obvious industries which are dominated by energy/FF inputs, like petrochemicals, fertilizer, aluminium and perhaps steel.

Such a system, of accounting for the embodied energy, would be the basis for an international carbon tax, which would be the best way to negate China's production advantage gained by using coal energy.

I would still say that the demarcation point should be transformation of energy into product, because after that, what happens to the product doesn't really matter, the energy input has been accounted for.

So for any business or country, the equation becomes primary energy in) = product out + primary energy out.

And measuring primary energy consumption is easy, and is already done. You just have to then measure additional primary energy inputs in later processess.

Every industry has a pretty good idea of what their embodied energy is - though they go to great lengths to hide it. That is why I like the carbon tax idea - it reveals it. And if country X doesn't want to track its carbon, then won;t be able to sell to any country that does.

So if the US just gets religion on a carbon tax (we already have one here, but it is useless), and imposes it on all domestic production and all imports, we would see quite an increase inn domestic manufacturing, and new, non technology specific incentive, for all renewable energy. And pseudo renewable,s like ethanol, would have their carbon content revealed for all to see.

Really, such a system of truth could only result in- anarchy!

Such a system, of accounting for the embodied energy, would be the basis for an international carbon tax

Sounds good to me!

I would still say that the demarcation point should be transformation of energy into product, because after that, what happens to the product doesn't really matter, the energy input has been accounted for.

That wouldn't account for non-energy things, like petrochemicals and ammonia. Let's say Trinidad decides to convert all of it's NG into ammonia, and export that to the US. Well, an analysis that didn't include ammonia would conclude that there was a serious drop in NG exports to the US, when in fact all that happened was that ammonia production moved from one place to another. Ceterus paribus, of course....

-----------------------------------------

I like the idea of a carbon tax. It would certainly require some kind of tariff for imports. Calculating that tariff seems difficult, but worth doing.

Let's say Trinidad decides to convert all of it's NG into ammonia, and export that to the US. Well, an analysis that didn't include ammonia would conclude that there was a serious drop in NG exports to the US, when in fact all that happened was that ammonia production moved from one place to another.

But if Trinidad had been exporting to the US, then there was a serious drop in NG exports, that is the point. The US can decide what to do with imported NG, as it is energy, but imported ammonia is not energy, just a manufactured product.

I don't think we should count product imports as energy, 'cos they aren't. BUT if we can account for the embodied energy, then we do get the true picture of the "energy footprint". Of course, the US per capita energy has been declining, but if we account for the embodied energy ion imported goods, I suspect it has been increasing, or at least , not declining as rapidly.

The carbon tax is, i think, the fairest possible system, except that it relies on the integrity of the producing country. In the case of China, that is dubious. It could also lead to game playing, where China states all its exporters use "clean" energy, and uses dirty energy for domestic stuff.

So, still some questions to be answered there.

But if Trinidad had been exporting to the US, then there was a serious drop in NG exports, that is the point.

Sure. But if the US no longer has to import NG in order to manufacture ammonia, then the drop in NG exports doesn't mean the same thing. IOW, it's not a problem.

The US can decide what to do with imported NG, as it is energy

True. This is just an example. In a complex market system there will be a lot of shifting around, and ceterus paribus will be hard to achieve. The point is simply that a drop in NG exports that is matched with an essentially equal increase in ammonia exports is a very, very different thing than a drop in NG exports alone. The former is a modest change, that may improve system efficiency, the other is a serious sign of trouble for both exporter and importer.

imported ammonia is not energy, just a manufactured product.

True. I'm not suggesting that it is. But, it needs to be included in any kind of analysis which is trying to come to meaningful conclusions about energy security.

Energy security is what the Original Post was about, as best I can tell. If the analysis misses important elements, then it's not useful.

I don't think we should count product imports as energy, 'cos they aren't. BUT if we can account for the embodied energy, then we do get the true picture of the "energy footprint".

I agree.

Of course, the US per capita energy has been declining, but if we account for the embodied energy ion imported goods, I suspect it has been increasing, or at least , not declining as rapidly.

It would be an interesting analysis. US manufacturing rose by 50% from 1980 to 2000, then declined slightly since China's entrance to the WTO. A complicating factor: Chinese manufacturing is much less energy efficient than US manufacturing.

The carbon tax is, i think, the fairest possible system, except that it relies on the integrity of the producing country. In the case of China, that is dubious. It could also lead to game playing, where China states all its exporters use "clean" energy, and uses dirty energy for domestic stuff.

I really don't think we could rely on Chinese self-reporting. We'd have to assign arbitrary averages, I think.

US manufacturing rose by 50% from 1980 to 2000, then declined slightly since China's entrance to the WTO. A complicating factor: Chinese manufacturing is much less energy efficient than US manufacturing.

But how are you measuring that 50% - by $ value? If so, that may not relate, at all, to the energy content. And even so, with mfring, many of the components are imported, so they have an embodied energy from elsewhere.

Chinese mfring is indeed much less efficient, that is why Jeff Rubin argued that a carbon tax, and high energy prices generally, are what can rescue many declining areas of US manufacturing, and I would agree.

Instead of all this wasted talk about international carbon agreements, the US should just lead from the front with a carbon tax, both domestic and on imports. domestic is levied according to measured primary carbon inputs. Imports are levied based on the average carbon of that country, unless that country can satisfy US requirements for carbon accounting (most OECD countries probably could).

Why should the US just do it - because they are the only market that is big enough that importers will comply, rather than just give up on that market. For China, the US is effectively saying we will tax your carbon emissions, and if you choose to keep using carbon(coal) then you keep paying the tax.

A trade war where the US can take the high moral, and environmental ground!

Set the tax at about $50/ton of carbon, increasing $10/yr to $100/ton. In gasoline terms, this is about $0.16/gal going to $0.30/gal. For domestic coal fired electricity (35% eff) this is an increase of 1.7 going to 3.4c/kWh- not enough to cause a panic, but enough to give a boost to renewables, and certainly enough to give a price disadvantage to Chinese and other carbon intensive imports.

Even the Cdn oilsands will have to pay it, but so be it - sure beats middle east oil.

Such a scheme gives industry some degree of certainty over what is going to happen, and , best of all, it does not involve "trading" so Wall St is out of it!

Of course, it must be matched by equivalent tax breaks in other areas, like reduction in corporate and income taxes. Less tax on business and employers, no tax on renewables, more tax on high carbon imported goods - all ingredients for boosting domestic industry, and encouraging efficient resource usage.

Let's get started!

But how are you measuring that 50% - by $ value?

Here's data at http://www.census.gov/manufacturing/m3/index.html, including http://www.census.gov/manufacturing/m3/historical_data/index.html , Historic Timeseries - SIC (1958-2001), "Shipments" http://www.census.gov/manufacturing/m3/historical_data/index.html.

with mfring, many of the components are imported, so they have an embodied energy from elsewhere.

I'm sure that these statistics account for imported components.

a carbon tax, and high energy prices generally, are what can rescue many declining areas of US manufacturing

More likely the Chinese would dramatically reduce energy consumption in manufacturing. Either would be good.

Instead of all this wasted talk about international carbon agreements, the US should just lead from the front with a carbon tax, both domestic and on imports. domestic is levied according to measured primary carbon inputs. Imports are levied based on the average carbon of that country, unless that country can satisfy US requirements for carbon accounting (most OECD countries probably could).

That's a great idea!

A trade war where the US can take the high moral, and environmental ground!

Would the WTO allow this??

3.4c/kWh- not enough to cause a panic, but enough to give a boost to renewables, and certainly enough to give a price disadvantage to Chinese and other carbon intensive imports.

I wonder if that's really enough to change prices significantly. Most manufacturing really isn't that power intensive. We really need calculations...

More likely the Chinese would dramatically reduce energy consumption in manufacturing.

I'm not sure they can do it quickly. To reduce the energy in steelmaking, for example, means major changes to steel mills - though if anyone can do it quickly, it would be them.

There is also the problem of shipping energy. Low value, high mass/volume items like wooden furniture, will have a high shipping carbon consumption relative to their value.

Things like Tv's, Ipods etc would be pretty much unaffected.

It would be interesting to see the WTO's take on it. Would they denounce a carbon tax, and demand that it be dismantled because it is a restraint of free trade? That would provoke some very interesting discussion, and lead some to question the relevance of the WTO.

The US is still the only country that can act unilaterally, and having had the world point the finger at it for carbon emissions, this is the best way I can think of to take action, and issue the challenge to everyone else, without transferring vast amounts of wealth to developing countries, as is currently being proposed in Cancun.

It leads by example and says to the developing countries that if you want to trade with the developed world, do so as clean as the developed world, otherwise, they can just trade with each other, and where is the money in that?

As for the electricity prices, keep in mind that large industrial customers only pay 4-5c for their electricity, so this is a BIG jump. Ditto for aluminium smelters in China, powered by coal electricity - yo can picture how their costs will change compared to hydro powered ones in Can/NZ/Chile etc.

At the retail elec level, it is not much of a difference, but would lessen the gap with wind power etc, so more people/companies/cities would opt to buy green power.

Best of all, the carbon tax can't be gamed or avoided - if company X is buying fuel, it is paying tax when it buys it! It then has to charge the sum of all its carbon taxes when it sells the product. It is not a deductible cost, because they charge out what they paid - the only way you can avoid it is to not buy carbon fuels, or carbon taxed supplies, in the first place.

A key part of the system is that the tax MUST be displayed/accounted for separately from the price of the good/service, and you MUST charge out equal to what you paid - so there is no hiding your carbon footprint. Customers can do carbon tax comparison shopping, whether they are buying fuel, a car, a can of beans or even services like lawyers, banks, etc.

It would be interesting then to se a carbon tax comparison of a Leaf and a Corolla, and of a solar panel made in China, new ordinary house compared to a "green" house, etc

And, it would do away with a lot of the false "green" claims we see on consumer products today.

Pair it up with country of origin labelling for fuels, and you have a real interesting conundrum - buy high carbon Cdn oilsands fuel, or low Carbon Saudi/Iraq fuel? The system really starts to empower consumers, through the price mechanism, only now it js the carbon price mechanism. I think this empowerment is actually the main reason why it is not being done!

To reduce the energy in steelmaking, for example, means major changes to steel mills - though if anyone can do it quickly, it would be them.

I have the impression that new Chinese steel plants are reasonably modern. The specific sources of inefficiency I'm aware of are 1) older coal plants, 2) small-scale diesel, and 3) hand manufacture in processes like li-ion batteries. Do you know of more?

The first two are reasonably straightforward to fix - just build the proper new generation. The hand manufacture - well, I'm not sure of the dynamics there.

more later...

Sense of deja vu here - you and I being the only commenters on a (now) old thread!

The main source of inefficiency is indeed the coal generation. They are building lots of new efficient stuff, and retiring old stuff, but they have a long way to go.

For something like steel, when you add in the shipping energy, and carbon tax it, China is at a disadvantage to domestic.

Small scale diesel is likely more an issue for villages, farms etc than factories. For hand made products, that have to be hand made, they will continue to be made there - the carbon tax won't bridge the labour cost gap.

The carbon tax would quickly identify the high carbon, high shipping energy, low value products, and those would start to get made domestically.

The carbon tax applies to everything, even food, so refridgerated produce from Chile, Mexico or China will have its price too. Same for air freighted produce that comes from Africa to the east coast. Instead of "food miles" we would have "food carbon", and that would be a boon to local producers. It would also lead to a shift towards more eating of things that are in season, instead of imported out of season stuff. It would be interesting to see the carbon content of some highly processed foods, and things like meat and dairy!

The "low fat diet" would be replaced with the "low carbon diet" - there could be quite some change in consumption patterns!

Sense of deja vu here - you and I being the only commenters on a (now) old thread!

Yes - a good conversation!

Small scale diesel is likely more an issue for villages, farms etc than factories.

I think this is a problem for all categories of Chinese industry, due to inadequate grid supplies - large entities are getting a substantial portion of their power from diesel. It's one of the wildcards for oil and coal consumption.

For hand made products, that have to be hand made, they will continue to be made there

I think one of the major hopes for US manufacturers of li-ion is to automate the winding process.

Same for air freighted produce that comes from Africa to the east coast.

One big effect that I know you're aware of: a shift from truck to rail. I think that some of the other effects of a carbon tax might surprise you: I think that large scale farming and transportation (especially with rail) is more energy-efficient than local truck farming, and water freight (say, from Chile to the US East Coast) is lower energy than rail freight (say, from California to the same destination).

Rubin makes a big deal of this, but I think he's over estimating the effect on international trade. One big factor: industry and transportation will increase efficiency, sometimes in unexpected ways. A shift from trucking to rail will give an advantage to very large farms. A shift from ground transportation to water would help intercontinental trade - for instance, more coal would move from Australia to China vs from the interior of China.

Another big factor: industry and shipping will become more energy efficient. When energy is cheap, reducing consumption is a low priority. When it becomes more expensive, very large shifts in efficiency or energy source are possible.

You have to remember the winner-take-all nature of market competition: there can be substitutes or energy efficiency strategies that are only slightly more expensive than the status quo which instantly would become useful if energy became more expensive.

One big effect that I know you're aware of: a shift from truck to rail. I think that some of the other effects of a carbon tax might surprise you: I think that large scale farming and transportation (especially with rail) is more energy-efficient than local truck farming, and water freight (say, from Chile to the US East Coast) is lower energy than rail freight (say, from California to the same destination).

This is true, but I don't consider California to NY local either. A greenhouse operation in the Catskills is what I call local, and if they heat their greenhouse with a biomass CHP (I hope to be doing just such a project for a greenhouse here next year) then they have a huge carbon advantage over Chile or Ca - though it will still be a seasonal business. All the Catskill operation has to do is get within 20% of the retail price of Ca/Chile, and then locals will buy them - if they know that half the price of the Chile ones are carbon tax. A food processor like Kraft would be a different story, of course.

Refrigerated storage/transport, in particular will be thing. We may see more food being processed in Chile first, but shipping and storing refrigerated fruit will have a very high carbon tax, even if the fruit is very cheap to start with. Every bit of spoilage still incurred a carbon cost, which must be recouped on the dale of the remainder. So we would see more trade in processed/packaged and less in fresh. It is a market opportunity for local grown fresh stuff - we'll see if they're up to it.

I still think Rubin is on the right track - the steel example is a good one - energy is a much bigger part of the cost than labor,but other things won;t be affected. I am sure the rail and shipping industries will lift their game, and that means the carbon tax is working!

In the US a shift from road to rail would be great, but not as easy as the Alan Drakes of the world would have us believe - on many lines there is not that much spare capacity, so a lot of double tracking would be needed, which takes time. But it will happen, and I am all for that.

The winner take all is exactly what we want - we just need to set up the rules of the game properly. In a carbon tax, the winner is the one that can reduce the carbon intensity of their operations, but you can have more companies "winning". In a cap and trade, the winner is simply the one that can dominate the market for buying credits, and the loser is the one that can't. We would probably see an opec like bloc of credit buyers form, to drive down the price - the big industrial emitters, the credit buyers, have much deeper pockets than the credit sellers, so I think they would win that round.

For small emitting companies, they would have to buy credits on the open/secondary market, at a much higher price. With the tax, that sort of strong arming just can't happen.

A greenhouse operation in the Catskills is what I call local, and if they heat their greenhouse with a biomass CHP (I hope to be doing just such a project for a greenhouse here next year) then they have a huge carbon advantage over Chile or Ca

Have you seen any analyses of greenhouse operations vs open-air? I'd love to see one. I've assumed that they were never directly competitive.

Refrigerated storage/transport, in particular will be thing. We may see more food being processed in Chile first, but shipping and storing refrigerated fruit will have a very high carbon tax, even if the fruit is very cheap to start with.

Electric rail can certainly be low-CO2; refrigeration can always be made more efficient with better insulation; and there are "reefer" units that are "charged" on land, using grid power, that don't need any inputs from the ship during transit.

I am sure the rail and shipping industries will lift their game, and that means the carbon tax is working!

Absolutely!

on many lines there is not that much spare capacity, so a lot of double tracking would be needed, which takes time. But it will happen, and I am all for that.

Yes.

I agree about cap and trade - it's a bad compromise.

Low value, high mass/volume items like wooden furniture, will have a high shipping carbon consumption relative to their value.

hmmm. Perhaps biomass like wood would be exempt.

Things like Tv's, Ipods etc would be pretty much unaffected.

Yes.

It would be interesting to see the WTO's take on it.

As I think about it, it might be like a value added tax, which Europe rebates on exports, thus effectively subsidizing exports. As long as it applied to all US production, it might be ok.

A key part of the system is that the tax MUST be displayed/accounted for separately from the price

This I think would be a mistake. A big part of the enormous advantage carbon taxes have over cap n trade is their simplicity: it takes advantage of the existing price system, and doesn't add more accounting.

It would be interesting then to se a carbon tax comparison of a Leaf and a Corolla, and of a solar panel made in China, new ordinary house compared to a "green" house, etc

Yes.

The system really starts to empower consumers, through the price mechanism, only now it js the carbon price mechanism. I think this empowerment is actually the main reason why it is not being done!

Absolutely: cap n trade was preferred because it's weaker.

A key part of the system is that the tax MUST be displayed/accounted for separately from the price

This I think would be a mistake. A big part of the enormous advantage carbon taxes have over cap n trade is their simplicity: it takes advantage of the existing price system, and doesn't add more accounting.

It has to be separated - if it is hidden, then how does the customer know how much carbon is embodied? All they can go on is total price. But when the carbon is explicitly stated, customers can, if they choose, buy on the basis of carbon content. Just like when buying yoghurt, I look at the sugar content - scary how much is in most, but my first criteria is low sugar, then I look at other attributes. If we are having this system, to quantify carbon, why hide it from the customer?

The other thing with cap and trade is that it doesn't reduce anything, unless you reduce the cap, and you can imagine the lobbying that would occur over gov decisions to lower the cap. With the tax, the decision is to set the price, and of carbon is still increasing, well then you can raise the tax (price). There would still be lobbying over that, of course, but it does mean no one is obligated to do anything, or caught buying the last allowable emissions at astronomical cost. Business has price stability, which they don;t have with cap and trade. That way, their only variable is to reduce carbon, not creative trading. Of course, company A, a carbon emitter, could still buy company B, a carbon sink, or even buy their carbon credits to offset carbon tax, but these are just normal business buying and selling decisions, which don;t have to go through a broker/market, though if I was a broker I would be trying to set up such a market.

It has to be separated - if it is hidden, then how does the customer know how much carbon is embodied? All they can go on is total price.

That's the beauty of it - customers don't have to juggle multiple variables.

But when the carbon is explicitly stated, customers can, if they choose, buy on the basis of carbon content. Just like when buying yoghurt, I look at the sugar content - scary how much is in most, but my first criteria is low sugar, then I look at other attributes.

If we set a Pigovian tax properly, then the cost of the carbon (including externalities like climate change) are included in the price of the product. If we, as a society, decide properly on how to price the cost of carbon, consumers no longer need to worry about adding it in - it's already in there.

If we are having this system, to quantify carbon, why hide it from the customer?

Oh, I wouldn't hide it. If the data is available, then I'd display it. The problem is that data is very, very hard to find. It would require a parallel accounting system: very complicated, very hard to regulate, easy to game, easy to get wrong.

Cost accounting is very, very hard to do. There are a lot of subjective judgment calls even with what you might think are simple hard costs. Part of the problem: indirect cost allocation - how do you allocate overhead costs? It's very, very hard to do. Expensive.

Well, we digress here, though I concede your system will be simpler, and for that reason alone more likely to be successful.

The simplest way for the carbon tax, domestically, is to charge the primary carbon producers (oil gas NG), at the mine/wellhead, just like an increased royalty, and let them price it into their product. then there is not tracking it through the system, and no carbon quantification at the point of sale. Great for a closed system, but then how do we account for imported goods (other than primary energy), when it has not been priced into a product? how do we know how much carbon is used for the made in china sofa when we aren't tracking it here?

I like a separate tax, as it allows carbon comparison shopping. if you have two competing products, one with high labour low carbon, and the other low labour high carbon, and they end up selling at the same price, how does the consumer decide? If the idea is to get people to reduce carbon usage then we should absolutely separate and highlight the tax. For the consumer, that means you not only get to shop low carbon, but you can actively shop to avoid paying a tax! How often do you get to choose how much or how little tax you pay, and given the choice, who wants to pay more tax?

It cant be addressed by product labelling, either. heinz uses x energy to make a can of beans, but the store in Cleveland has used less energy to get the beans there than the one in Fairbanks, Alaska, so it can charge less carbon tax.

but to implement my system is more complex, as each buyer has to pay carbon tax on inputs, and collect it on outputs. How do you allocate the carbon tax for heating head office to 23 different product lines that get shipped to 50 states?

And we still have the issue of evaluating imports. Even if we had a "worldwide" carbon tax, levied equally by all countries, how can we be sure China is actually charging it, or not rebating it back in some other way, or only loading it all on domestic consumption and not exports?

The more I think about it, the harder it becomes to implement. Maybe it is just the country's carbon use per $GDP, applied to all imports from that country. Fine for China but for say Canada, that lumps averages the low carbon exporters and the high carbon ones.

Hmm, have to think about that one while I put some more coal on the fire....

Pau & Nick,

Congratulations on creating one of TOD's longer sustained threads of intelligent, on-topic conversation!

You should consider editing the ideas and offering them up as a joint guest post.

Regards,

Jon

Thanks!

That's a funny comment on the S/N ratio here...

Regarding a joint post: that would be fun. What do you think, Paul?

Hi Jon,

Thanks for the compliments - you may be able to tell that Nick and I have done this several times before, on different topics. Probably would be easier by email exchange, but this way everyone gets to see it, and can contribute.

The carbon tax is an interesting one, and is a classic "devil in the details" situation. It would have to be very carefully done to avoid gaming, especially with imports, and to low enough to be palatable and yet high enough to actually achieve change.

Here in BC, we have a carbon tax, but it is not applied to imported goods (too difficult, for reasons discussed above) , and the tax is hidden in consumer pricing, and the tax rate is too small to really make a difference to anyone's buying decisions!

Here is the tax schedule, more info here; http://www.sbr.gov.bc.ca/documents_library/notices/British_Columbia_Carb...

July 1, 2009 ‐ $15 per tonne of CO2e emissions

July 1, 2010 ‐ $20 per tonne of CO2e emissions

July 1, 2011 ‐ $25 per tonne of CO2e emissions

July 1, 2012 ‐ $30 per tonne of CO2e emissions

While I don;t agree with many policies of the BC govt, I do approve of this one - it took real political backbone to implement it, and is probably the first new tax in history that was actually politically popular!

The $30/ton CO2 works out to $0.27/gal for gasoline, or $1.50/MMBTU for NG- is that enough to make any real difference? Are there alternatives available to any customers?

Ethanol does not attract the carbon tax, but its inputs would, and with something like 50,000 btu's of NG for a gallon of ethanol, the producer has to pay about 8c of carbon tax on that, and carbon tax is paid on fuel to transport it, etc. But, there is the (small) incentive to use carbon neutral fuel as input, or waste heat.

AS for a joint post, interesting idea, if we can agree on enough! We are two pragmatists that approach the same issues from quite different directions.

I haven't forgotten your invitation to Seattle - I will probably be doing a trip to Portland in Feb, to check out a woodgas-electricity system, so will let you know when I do.

Cheers,

Paul

The $30/ton CO2 works out to $0.27/gal for gasoline, or $1.50/MMBTU for NG- is that enough to make any real difference?

For corporate industrial/commercial customers, the answer is definitely yes. That's more than enough to make the difference in a lot of close competitive purchasing/bidding situations.

Are there alternatives available to any customers?

Rail vs trucking; coal vs NG; NG vs wind; EVs vs ICE.

By far the most important influence is on pricing: there would be many, many more situations where prices would change for various products, though that wouldn't necessarily be known or thought about by the buyers or, indeed, any of the participants.

That's the beauty of a market system: no one has to think about anything but price, and the infinitely complex ramifications of the carbon tax would ripple through the whole economy, causing myriad changes that no one has to think about - just follow the price signals.

By alternatives, I was actually thinking about renewable alternatives to NG.

For the tax to be effective, it must incentivise customers to move from coal to NG, and from NG to something else. But the price gap between coal and NG is much larger than $30/ton, and the coal users (power stations and steel mills) can't re-equip easily, so I'm not sure how much of a shift we would really see. For the (non transport)NG users, unless they are near an anaerobic digestion system, or a source of biomass, they have no real alternative, other than efficiency projects, and possibly shifting to electricity (e.g. heat pumps) but they have a big price differential to overcome.

So for the non transport "fuel burners" they will mostly have little alternative - the tax will simply raise the price of all goods they produce.

That is the thing about the tax being effective - if the fuel burners are not switching to something else, is the tax working?

Transport is different, of course, rail and CNG ( and even ethanol) would be the winners. EV's are already so cheap for "fuel" that it would make no difference there - the hurdle is, and will always be first cost - though creative leasing can get around that.

The other side of the carbon tax coin, is those doing sequestering, who will want to claim a tax credit. Some farmers and woodlot owners claim they are sequestering, but how do you quantify that? Even a landfill is a form of sequestering!

I would want some very strict rules on sequestering, AND it has to be done here, not a forest in Chile, etc.

For the tax to be effective, it must incentivise customers to move from coal to NG, and from NG to something else.

I'd say incentivization of efficiency will be at least as important as fuel switching, and probably much more so.

The thing to keep in mind here: the current complex array of production and consumption systems have been optimized for a certain set of low-energy costs. If those costs change even moderately, there is an enormously complex set of changes that will take place.

Every day production managers (and individual consumers, with a much lower level of analysis) make a wide variety of choices, many of them based on very small cost differences. Over time, a modest cost change can mean much more change than you might expect.

Now, as far as coal vs NG vs wind vs solar: every user, especially large industrial users, is optimizing all of the time. Coal will get used where it's cheaper, including all of it's costs, such as opportunity, storage, transport, etc. Even a small price shift will cause someone, somewhere to move on a cost/benefit curve from coal to NG, coal to wind, etc.

Regarding sequestration: good questions. I'm not sure. One thought: any change in prices involves windfall profits for people in the right position, but we accept that cost for the greater benefits of a flexible market system. If sequestration really is beneficial (and it probably is), we may need to accept windfall profits here, too.

Efficiency is certainly important, and there are many projects that don;t get done presently as the payback is not deemed good enough. When it comes to fuel switching, there is always the risk of industry relocation! A coal fired alum smelter might find it a better decision to move to China rather than switch to NG or whatever else. That is exactly what we don;t want, but some industry has definitely migrated to lower energy places.

What we do want is a more efficient, lower carbon industry here, rather than a less efficient, higher carbon, cheaper industry there.

With coal, one change that can then be made is allowing elec customers to choose their source, and the sources will have different prices. There is already some of this, of course, where you can buy green power. But when the factory can choose coal, NG or other, then there is a price signal. Big change for the elec industry, but a good one, I think. It will lay out the reality of all generation sources.

Since elec is the biggest user of coal, this is where the biggest difference can happen. A coal plant that (somehow) manages co@ sequestration has and advantage, though the cost of achieving that is likely more than their advantage - no one yet has a successful coal CO2 sequestration system.

I have no problem with people making money of sequestration, though I can;t see how they will get more than what the tax is. What I don;t want is system gaming, and projects that"predict" if we do X then Y tons of Co2 will be sequestered over Z years. Now, someone can do a project, and make that claim, and even forward sell the rights to their credits to someone else (like gold mines do with future production) BUT there are no actual credits created until a ton is actually sequestered. So the forest only gets so many credits per year, as measured by a certified third party.

There has to absolute integrity in sequestration measuring. I have no problem with windfall profits, i have a problem with fraudulent profits, and the scam artists will be waiting. Even industry is not immune - the pulp industry got their "money for nothing" by blending diesel with black liquor they were already producing and burning, and then got billions in tax credits for a "biofuel". It is biologically sourced, but you can;t burn it in a diesel engine, which was the purpose of the credit. The pulp mills got about $4bn out of that before the loophole was closed.

American businesses are the masters of system gaming - we have to make sure they game it in a way that actually achieves something, not just paper shuffling!

Sounds reasonable.

Yes, international trade is a problem.

how do we know how much carbon is used for the made in china sofa when we aren't tracking it here?

I'm not sure our data is useful. OTOH, it would be much better than nothing.

The simplest approach: get domestic numbers either from industry statistics, or do some intensive study of a small sample in each industry in the US (or Canada), and apply those numbers to imports. That would at least put domestic and imported products on a level playing field.

Possibly the next step would be to 1) adjust those numbers (probably upwards) if data was available from the country of origin, and 2) allow appeals (downwards) by individual importers with good, transparent data.

Nick, I'm up for a joint post, though it will take some time and effort to turn this into one.

The problem with using industry statistics is that the innovators get lumped in with everyone else. Yes, they can appeal it, but these are typically the smallest producers of X, who have the least time and money to go through any such process! If their larger competitors appeal the appeal, they can outlast the small guy. And then when you make a change, do you have to go through it again? It would be like a mini version of the Public Utilities Commissions that many States have. They do have simplified rules for small utilities, but they are still onerous.

BC just avoided the whole problem of taxing imports. And a domestic exporter is at a disadvantage as they are paying carbon tax that their out of province/country competitors aren't. You could allow them a refund on the portion of production exported, though you can see already where this would be gamed by them trying to claim the exported products use more carbon. Worse, it provides no incentive for an exporter to reduce carbon.

How were imports treated under cap and trade?

I'm up for a joint post, though it will take some time and effort to turn this into one.

hmmm. Yes, it would be a bit of a project. A dialogue is a lot easier than a properly researched, organized and edited paper. hmmm...

The problem with using industry statistics is that the innovators get lumped in with everyone else.

I think that if a US average were used, it would be hard for a Chinese company to get significantly below it. That might be an argument for not using anything higher than the US industry average.

If their larger competitors appeal the appeal, they can outlast the small guy.

I don't think you'd let companies appeal anything but their own assessment.

How were imports treated under can and trade?

I'm not sure - we could look at the sulfur version, or the recent CO2 proposals. I'm pretty sure they didn't try to deal with imports, though.

Even using the US average is difficult - what is the average for a US made sofa? In fact, what is an average US made sofa? A modern style two seater will have vastly different materials and labour inputs than an old style overstuffed one, and a leather one is different again? So even with the US, there will be a wide variation.

And then who audits the mom and pop operation in India? (I am corresponding with one presently that hand builds steam engines!) The compliance costs for a small volume company would be such that they just wouldn't bother.

The only way you can do that is if the carbon tax is cascading, like GST. But if it is only levied on the sale of carbon fuels, there is no way to track it.

I don't think you'd let companies appeal anything but their own assessment.

It solves one problem but that puts a LOT of power in the hands of the determining authority - opens up the way for corruption/political influence?

I've never looked at the Montreal protocol (sulphur, not poutine or hockey), but they had it easy as there are relatively few emitters of sulphur, and they are all industrial entities.

Maybe we just call a spade a spade, and have a carbon tax on ALL imports, on $ value and the carbon usage of the exporting country, no company. If you don;t want to pay the tax, then set up shop in the US. I guess there could be a process where you could have your facility audited by US inspectors, to US standards. For the small guy, cheaper to just eat the tax. But for some, like automakers, it would be worth it.

I wonder if there has ever been any discussion of this at WTO - it would make existing trade deals look simple by comparison!

I don't think you'd let companies appeal anything but their own assessment. - It solves one problem but that puts a LOT of power in the hands of the determining authority - opens up the way for corruption/political influence?

The local property tax appeals process in the US is somewhat comparable. AFAIK, local property taxes can generally only be appealed by the taxpayer. OTOH, I've seen property tax appeals where affected taxing bodies are allowed to intercede to provide information to support the existing assessment (I imagine transparency would help a lot with corruption - OTOH, there would be problems with corporate trade secrets).

Have you seen other models for tax assessment appeals?

Maybe we just call a spade a spade, and have a carbon tax on ALL imports, on $ value and the carbon usage of the exporting country, no company.

Probably the primary purpose of an import tax is to preserve an equal playing field for domestic companies. That would be the basis that could be most easily defended against charges of protectionism.

To defend against charges of protectionism, we would probably take the lowest of the alternatives, where available: the domestic industry average; the foreign national average; the foreign national industry average; and the foreign individual company audited data.

I wonder if there has ever been any discussion of this at WTO

Me too. I suspect that the European cap and trade doesn't try to tax imports. OTOH, the European C&T is so weak it doesn't matter.

Rembrandt,

I agree with points 1) and 2) but we mustn't forget that the largest reserves of all are found in Venezuela (176 Tcf according to the EIA). And Venezuelan gas fields are largely on land or in shallow water allowing for easy development in a different political regime. It's also worth noting that Brazil's offshore gas fields so far are high-pressure, high-temperature and high-technology and thus will probably be a lot slower coming on line.

With respect to the consumption side, the article you provide suggests that even as natural gas production increases in nations like Bolivia and Brazil (and Venezuela), more and more will be consumed internally to spur economic development in heavy industry and agriculture.

This is precisely what every current importer has done with their own indigenous or imported natural gas and it is unreasonable to expect that those developing nations that can ramp up production will be willing to remain economic backwaters that simply export raw materials to the OECD.

I don't think it is a wise long term plan to assume that the global LNG market will remain as oversupplied as it is today. LNG will become more expensive over the next decade.

@jonathan

It depends a lot on what one expects of the institutional/political factors in each country in the future. I think it is more likely that Brazilian deepwater gas reserves will be developed before Venezuela has a political regime change and can attract the required capital to develop its gas reserves.

I think the main point of the article you wrote, which is part of the bigger trend, is that more and more will processing of resources take place at the point of extraction. Due to a variety of factors (more costly extraction, economic development, political decision). But that fact is being ignored in the 'service' economies whose leaders think they can do away with resources (at least to a large extent).

Thanks for chipping in in the comments.

Rembrandt

Good post, but there is a mistake in the map. Bahía Blanca, Argentina is not where it is shown at (in the city of Buenos Aires, in front of Montevideo), rather a long way to the South, round that bulge.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bah%C3%ADa_Blanca

Thanks for pointing that out. Unfortunately, the map is borrowed from another site and I can't fix it.

I was about to point out that.

_____

wordpress themes

web hosting

Burning LNG for critical applications like electricity seems like a sandwich in a can. The effort and theatre that goes into it seems way out of proportion to the end product. Electricity generation should be resilient and use local resources. Therefore I see growing LNG import dependence as a bad sign.

If CNG replaces expensive diesel in trucks and buses that will further increase global gas demand, maybe by 20% or more. With talk of carbon taxes more baseload electricity will come from combined cycle gas plant not coal fired. Gas generators also have low capital cost, fast construction times and can use air cooling. As mentioned a lot of NG is embodied in nitrogen fertilisers and demand must increase.

Eventually gas demand will outstrip supply of both piped gas and shipped LNG. Prices must increase. That is despite supposedly huge reserve increases from shale gas fracking, coal seam gas and offshore NG. Growing dependence on LNG is just compounding the mistakes we have already made with oil. Instead of imported LNG emerging economies should aim to get their new energy from non-carbon based sources.