Galactic Scale Energy, Part 2: Can Economic Growth Last?

Posted by Euan Mearns on July 29, 2011 - 11:29am

This is a guest post by Tom Murphy. Tom is an associate professor of physics at the University of California, San Diego. This article is Part 2 of a two-part assessment of the implications of continued growth. Part 1 appeared here. Both articles first appeared at Do The Math.

As we saw in the previous post, the U.S. has expanded its use of energy at a typical rate of 2.9% per year since 1650. We learned that continuation of this energy growth rate in any form of technology leads to a thermal reckoning in just a few hundred years (not the tepid global warming, but boiling skin!). What does this say about the long-term prospects for economic growth, if anything?

The figure above shows the rate of global economic growth over the last century, as reconstructed by J. Bradford DeLong. Initially, the economy grew at a rate consistent with that of energy growth. Since 1950, the economy has outpaced energy, growing at a 5% annual rate. This might be taken as great news: we do not necessarily require physical growth to maintain growth in the economy. But we need to understand the sources of the additional growth before we can be confident that this condition will survive the long haul. After all, fifty years does not imply everlasting permanence.

The difference between economic and energy growth can be split into efficiency gains—we extract more activity per unit of energy—and “everything else.” The latter category includes sectors of economic activity not directly tied to energy use. Loosely, this could be thought of as non-manufacturing activity: finance, real estate, innovation, and other aspects of the “service” economy. My focus, as a physicist, is to understand whether the impossibility of indefinite physical growth (i.e., in energy, food, manufacturing) means that economic growth in general is also fated to end or reverse. We’ll start with a close look at efficiency, then move on to talk about more spritely economic factors.

Exponential vs. Linear Growth

First, let’s address what I mean when I say growth. I mean a steady rate of fractional expansion each year. For instance, 5% economic growth means any given year will have an economy 5% larger than the year before. This leads to exponential behavior, which is what drives the conclusions. If you object that exponentials are unrealistic, then we’re in agreement. But such growth is the foundation of our current economic system, so we need to explore the consequences. If you think we could save ourselves much of the mess by transitioning to linear growth, this indeed dramatically shifts the timeline—but it’s also a death knell for economic growth.

Let’s say we lock in today’s 5% growth and make it linear, so that we increase by a fixed absolute amount every year—not by a fixed fraction of that year’s level. We would then double in 20 years, and in a century would be five times bigger (as opposed to 132 times bigger under exponential 5% growth). But after just 20 years, the fractional growth rate is 2.5%, and after a century, it’s 1%. So linear growth starves the economic beast, and would force us to abandon our current debt-based financial system of interest and loans. This post is all about whether we can maintain our current, exponential trajectory.

Squeezing Efficiency: Rabbits out of the Hat

It seems clear that we could, in principle, rely on efficiency alone to allow continued economic growth even given a no-growth raw energy future (as is inevitable). The idea is simple. Each year, efficiency improvements allow us to drive further, light more homes, manufacture more goods than the year before—all on a fixed energy income. Fortunately, market forces favor greater efficiency, so that we have enjoyed the fruits of a constant drum-beat toward higher efficiency over time. To the extent that we could continue this trick forever, we could maintain economic growth indefinitely, and all the institutions that are built around it: investment, loans, banks, etc.

But how many times can we pull a rabbit out of the efficiency hat? Barring perpetual motion machines (fantasy) and heat pumps (real; discussed below), we must always settle for an efficiency less than 100%. This puts a bound on how much gain we might expect to accomplish. For instance, if some device starts out at 50% efficiency, there is no way to squeeze more than a factor of two out of its performance. To get a handle on how much there is to gain, and how fast we might expect to saturate, let’s look at what we have accomplished historically.

The Good, the Bad, and the Average

A few shining examples stand out. Refrigerators use half the energy that they did about 35 years ago. The family car that today gets 40 miles per gallon achieved half this value in the 1970′s. Both cases point to a 2% per year improvement (doubling time of 35 years).

Not everything has seen such impressive improvements. The Boeing 747 established a standard for air travel efficiency in 1970 that has hardly budged since. Electric motors, pumps, battery charging, hydroelectric power, electricity transmission—among many other things—operate at near perfect efficiency (often around 90%). Power plants that run on coal, natural gas, or nuclear reactions have seen only marginal gains in efficiency in the last 35 years: well less than 1% per year.

Taken as a whole, we might then loosely guess that overall efficiency has improved by about 1% per year over the past few decades—being bounded by 0% and 2%. This corresponds to a doubling time of 70 years. How many more doublings might we expect?

Potential Gains and Limits

Many of our large-scale applications of energy use heat engines to extract useful energy out of combustion or other source of heat. These include fossil-fuel and nuclear power plants operating at 30–40% efficiency, and automobiles operating at 15–25% efficiency. Heat engines therefore account for about two-thirds of the total energy use in the U.S. (27% in transportation, 36% in electricity production, a bit in industry). The requirement that the entropy of a closed system may never decrease sets a hard limit on how much efficiency one might physically achieve in any heat engine. The maximum theoretical efficiency, in percent, is given by 100×(Th−Tc)/Th, where Th and Tc denote absolute temperatures (in Kelvin) of the hot part of the heat engine and the “cold” environment, respectively. Engineering limitations prevent realization of the theoretical maximum. But in any case, a heat engine operating between 1500 K (hot for a power plant) and room temperature could at most achieve 80% efficiency. So a factor of two improvement is probably impractical in this dominant domain.

The reverse of a heat engine is a heat pump, which uses a little bit of energy to move a lot. Air conditioners, refrigerators, and some home heating systems use this technique. Somewhat magically, moving a certain quantity of heat energy can require less than that amount of energy to accomplish. For cooling applications, the thermodynamic limit to efficiency is given by 100×Tc/(Th−Tc), again expressing temperatures on an absolute scale. A refrigerator (usually a freezer with a piggybacked refrigerator) operating at room temperature can theoretically achieve 1100% efficiency. The Energy Efficiency Ratio (EER), which is displayed for most new cooling devices, is theoretically bounded by 3.4×Tc/(Th−Tc), which in this example is 36. Today’s refrigerators achieve EER values of about 12, so that only a factor of three remains. The same can be said for the Coefficient of Performance (COP) for heat pumps, which is bounded by Th/(Th−Tc). Like refrigerators, these are performing within a factor of 2–3 of theoretical limits.

Lighting has seen dramatic improvements in recent decades, going from incandescent performances of 14 lumens per Watt to compact fluorescent efficacies that are four times better, at 50–60 lumens per Watt. LED lighting currently achieves 60–80 lumens per Watt. An ideal light source emitting a spectrum we would call white (sharing the exact spectrum of daylight) but contrived to have no emission outside our visible range would have a luminous efficacy of 251 lm/W. The best LEDs are now within a factor of three of this hard limit.

The efficiency of gasoline-powered cars can not easily improve by any large factor (see heat engines, above), but the effective efficiency can be improved significantly by transitioning to electric drive trains. While a car getting 40 m.p.g. may have a 20% efficient gasoline engine, a battery-powered drive train might achieve something like 70% efficiency (85% efficiency in charging batteries, 85% in driving the electric motor). The factor of 3.5 improvement in efficiency suggests effective mileage performance of 140 m.p.g. One caution, however: if the input electricity comes from a fossil-fuel power plant operating at 40% efficiency and 90% transmission efficiency, the effective fossil-to-locomotion efficiency is reduced to 25%, and is not such a significant step.

As mentioned above, a broad swath of common devices already operate at close to perfect efficiency. Electrical devices in particular can be quite impressively frugal with energy. That which isn’t used constructively appears as waste heat, which is one way to quickly assess efficiency for devices that do not have heat generation as a goal: power plants are hot; car engines are hot; incandescent lights are hot. On the flip side, hydroelectric plants stay cool, LED lights are cool, and a car battery being charged stays cool.

Summing it Up

Given that two-thirds of our energy resource is burned in heat engines, and that these cannot improve much more than a factor of two, more significant gains elsewhere are diminished in value. For instance, replacing the 10% of our energy budget spent on direct heat (e.g., in furnaces and hot water heaters) with heat pumps operating at their maximum theoretical efficiency effectively replaces a 10% expenditure with a 1% expenditure. A factor of ten sounds like a fantastic improvement, but the overall efficiency improvement in society is only 9%. Likewise with light bulb replacement: large gains in a small sector. We should still pursue these efficiency improvements with vigor, but we should not expect this gift to provide a form of unlimited growth.

On balance, the most we might expect to achieve is a factor of two net efficiency increase before theoretical limits and engineering realities clamp down. At the present 1% overall rate, this means we might expect to run out of gain this century. Some might quibble about whether the factor of two is too pessimistic, and might prefer a factor of 3 or even 4 efficiency gain. Such modifications may change the timescale of saturation, but not the ultimate result.

Faith in Technology

We have developed an unshakable faith in technology to address our problems. Its track record is most impressive. I myself can sit at my dining room table in California and direct a laser in New Mexico to launch pulses at the astronaut-placed reflectors on the moon and measure the distance to one millimeter. I built much of the system, so I am no stranger to technology, and embrace the possibilities it offers. And we’ve seen the future in our movies—it’s almost palpably real. But we have to be careful about faith, and periodically reexamine its validity or possible limits. Following are a few key examples.

What About Substitutions?

The previous discussion is rooted in the technologies of today: coal-fired power plants, for goodness sake! Any self-respecting analysis of the long term future should recognize the near-certainty that tomorrow’s solutions will look different than today’s. We may not even have a name yet for the energy source of the future!

First, I refer you to the previous post: the continued growth of any energy technology—if consumed on the planet—will bring us to a boil. Beyond that, we hit astrophysically nonsensical limits within centuries. So energy scale must cease growth. Likewise, efficiency limits will prevent us from increasing our effective energy available without bound.

Second, you might wonder: can’t we consider solar, wind and other renewables to be more efficient than fossil fuel power, since the energy has free delivery? It’s true that unlike the business model for the printer (cheap printer, expensive ink cartridges that ruin you in the end), the substantial cost for renewables is in the initial investment, with little in the way of consumables. But fossil fuels—although a limited-time offer—are also a free gift of nature. We do have to put effort into retrieving them (delivery not free), although far less than the benefit they deliver. The important metric on the energy/efficiency front is energy return on energy invested (EROEI). Fossil fuels have enjoyed EROEI values typically in the range of 20:1 to 100:1, meaning that less than 5% of the eventual benefit must be invested up front. Solar and wind are less, at 10:1 and 18:1, respectively. These technologies would avoid wasting a majority of the energy in heat engines, but the lower EROEI means it’s less of a freebee than the current juice. And yes, the 15% efficiency of many solar panels does mean that 85% goes to heating the dark panel.

What About Accomplishing the Same Tasks with Less?

One route to coping with a fixed energy income is to invent new devices or techniques that accomplish the same tasks using less energy, rather than incrementally improve on the efficiency of current devices. This works marvelously in some areas (e.g., generational changes in computers, cell phones, shift to online banking/news).

But some things are hard to shave down substantially. Global transportation means pushing through air or water over vast distances that will not shrink. Cooking means heating meal-sized portions of food and water. Heating a home against the winter cold involves a certain amount of thermal energy for a fixed-size home. A hot shower requires a certain amount of energy to heat a sufficient volume of water. Can all of these things be done more efficiently with better aero/hydrodynamics or traveling more slowly; foods requiring less heat to cook; insulation and heat pumps in homes; and taking showers using less water? Absolutely. Can this go on forever to maintain growth? No. As long as these physically-bounded activities comprise a finite portion of our portfolio, no amount of gadget refinement will allow indefinite economic growth. If it did, eventually economic activity would be wholly dominated by us “servicing” each other, and not the physical “stuff.”

What About Paying More to Use Less?

Owners of solar panels or Prius cars have elected to plunk down a significant amount of money to consume fewer resources. Sometimes these decisions are based on more than straight dollars and cents calculations, in that the payback can be very long term and may not be competitive against opportunity cost. Could social conscientiousness become fashionable enough to drive overall economic growth? I suppose it’s possible, but generally most people are only interested in this when the cost of energy is high to start with. Below, we’ll see that if the economy continues its growth trend after energy use flattens, the cost of energy becomes negligibly small—deflating the incentive to pay more for less.

The Unphysical Economy

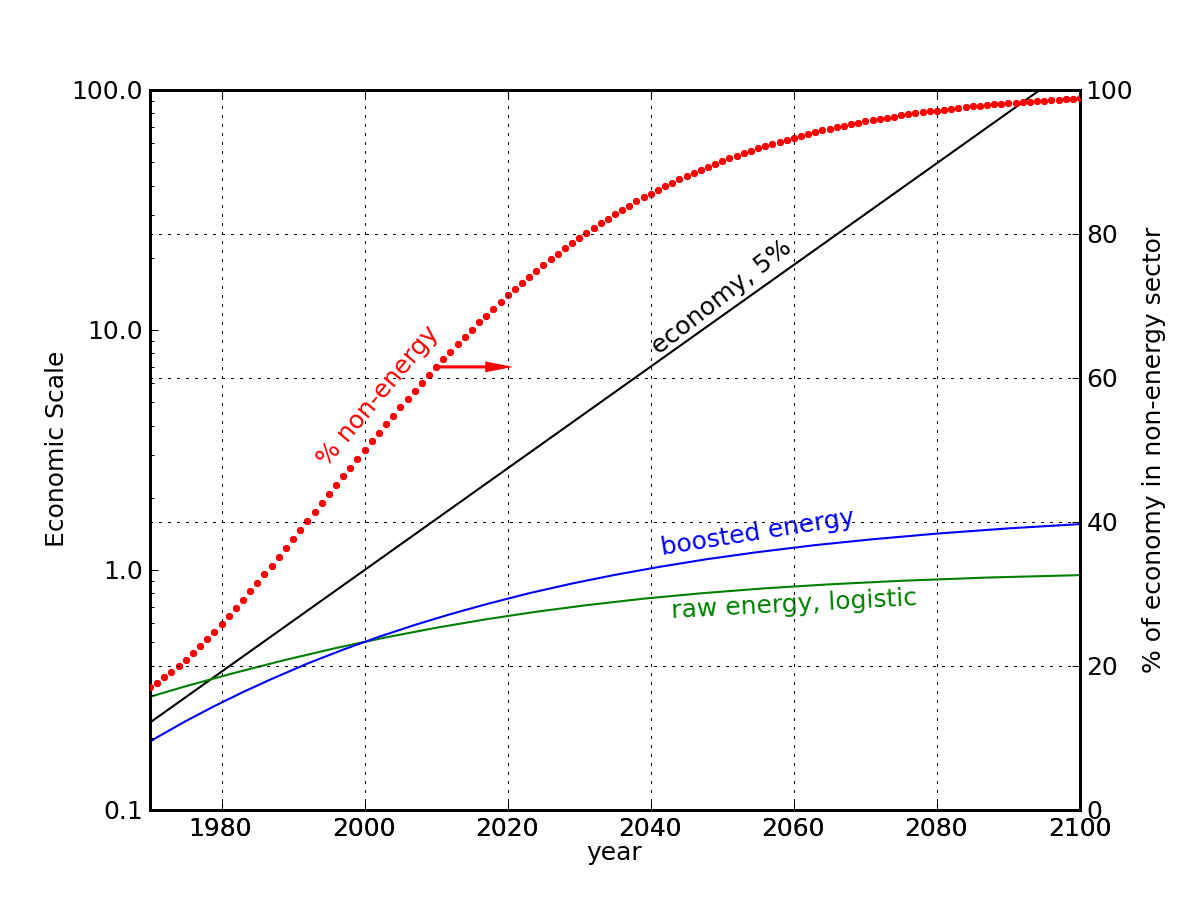

In a future world where energy growth has ceased, and efficiency has been squeezed to a practical limit, can we still expect to grow our economy through innovation, technology, and services? One way to approach the problem is to demand that we maintain 5% economic growth over the long term, and see what fraction of economic activity has to come from the non-energy-demanding sector. Of course all economic activity requires some energy, so by “non-energy” or “unphysical,” I mean those activities that require minimal energy inputs and approach the economist’s dream of “decoupling.”

We start by setting energy to flatten out as a logistic function (standard S-curve in population studies), with an inflection point at the year 2000 (halfway along). We then let efficiency boost our effective energy at the present rate of 1% gain per year, ultimately saturating at a factor of two. The figure below provides a toy example of how this might look.

The timescale is not the important feature of the figure. The important result is that trying to maintain a growth economy in a world of tapering raw energy growth (perhaps accompanied by leveling population) and diminishing gains from efficiency improvements would require the “other” category of activity to eventually dominate the economy. This would mean that an increasingly small fraction of economic activity would depend heavily on energy, so that food production, manufacturing, transportation, etc. would be relegated to economic insignificance. Activities like selling and buying existing houses, financial transactions, innovations (including new ways to move money around), fashion, and psychotherapy will be effectively all that’s left. Consequently, the price of food, energy, and manufacturing would drop to negligible levels relative to the fluffy stuff. And is this realistic—that a vital resource at its physical limit gets arbitrarily cheap? Bizarre.

This scenario has many problems. For instance, if food production shrinks to 1% of our economy, while staying at a comparable absolute scale as it is today (we must eat, after all), then food is effectively very cheap relative to the paychecks that let us enjoy the fruits of the broader economy. This would mean that farmers’ wages would sink far lower than they are today relative to other members of society, so they could not enjoy the innovations and improvements the rest of us can pay for. Subsidies, donations, or any other mechanism to compensate farmers more handsomely would simply undercut the “other” economy, preventing it from swelling to arbitrary size—and thus limiting growth.

Another way to put it is that since we all must eat, and a certain, finite fraction of our population must be engaged in the production of food, the price of food cannot sink to arbitrarily low levels. The economy is rooted in a physical world that has historically been joined at the hip to energy use (through food production, manufacturing, transport of goods in the global economy). It is fantastical to think that an economy can unmoor itself from its physical underpinnings and become dominated by activities unrelated to energy, food, and manufacturing constraints.

I’m not claiming that certain industries will not grow: there will always be growth in some sector. But net growth will be constrained. Winners will not outpace the losers. Nor am I claiming that some economic activities cannot exist virtually independent of energy. We can point to plenty of examples of this today. But these things can’t grow to 90%, then 99%, then 99.9%, etc. of the total economic activity—as would be mandated if economic growth is to continue apace.

Where Does this Leave Us?

Together with the last post, I have used physical analysis to argue that sustained economic growth in the long term is fantastical. Maybe for some, this is stating the obvious. After all, Adam Smith imagined a 200-year phase of economic growth followed by a steady state. But our mentality is currently centered on growth. Our economic systems rely on growth for investment, loans, and interest to make any sense. If we don’t deliberately put ourselves onto a steady state trajectory, we risk a complete and unchoreographed collapse of our economic institutions.

Admittedly, the argument that economic growth will stop is not as direct a result of physics as is the argument that physical growth will stop, and as such represents a stretch outside my usual comfort zone. But besides physical limits, I think we must also apply notions of common sense and human psychology. The artificial world that must be envisioned to keep economic growth alive in the face of physical limits strikes me as preposterous and untenable. It would be an existence far removed from demonstrated modes of human economic activity. Not everyone would want to participate in this whimsical society, preferring instead to spend their puffy paychecks on constrained physical goods and energy (which is now dirt cheap, by the way, so a few individuals could easily afford to own all of it!).

Recognizing the need to ultimately transition to a non-growth economy, I am personally disconcerted by the fact that we lack a tested economic system based on steady-state conditions. I would like to take a conservative, low-risk approach to the future and smartly place ourselves on a sustainable trajectory. There are well-developed steady-state economic models, pioneered by Herman Daly and others. There are even stepwise plans to transition our economy into a steady-state. But not one of those steps will be taken if people (who elect politicians) do not crave this result. The only way people will crave this result is if they understand (or experience) the impossibility of continued growth and the consequences of not acting soon enough. I hope we can collectively be smart enough to make this transition.

Acknowledgments: Thanks to Brian Pierini for his review and comments.

Related articles on the Oil Drum

Steven Balogh and Hannes Kunz

Revisting the Fake Fire BrigadeJoules Burn

American Physical Society Report on Energy EfficiencyHerman Daly

From a Failed Growth Economy to a Steady State EconomyTowards a Steady State Economy

Nate Hagens

A Net Energy Parable: Why is ERoEI Important?Dear Candidate: What Will You Do if Growth is Over?

Euan Mearns

The energy efficiency of cars

I should be impressed by all this, but I'm not. Too much qualitative, not enough quantitative (despite the charts). Little credit given, perhaps not even understood, to human characteristics.

As Hawkings said, we're capable of building our own genes now.

On the contrary, I think this is a great article, because it uses a minimum of numbers to deduce it's conclusions. It shows that the

actual numbers are irrelevant because economic growth as it is defined now cannot continue much longer.

Yes we can manipulate genes. Sort of. Can you tell me the code for Superman? (I worked on the human genome project).

What this article doesn't talk about is human numbers. Population. We have finite, indeed declining natural resources. We have growing population. We can grow the quality of life long term for the average human being only by reducing the supply of human beings.

That is the bottom line. We in the OECD (even the poorest of us) live like kings compared to half the world's population. We cannot bring them up to our standard of living. There is not enough land to raise the cattle.

We all need to eat lower down the food chain and we need population control and we need it yesterday.

When the inequality in the world has fallen from 1000 to 1 to 10 to 1 then we can talk about growing the economy for us lucky few.

The snippet below exemplifies the problems of a growth political system.

How do we build a political system in which the lack of the ability in an individual to gather resources without conflict results in eating lower down the food chain and lower procreation? Perhaps, the old Chinese custom that saving a life means that one is legally responsible for that life forever would do this. Perhaps the outlawing of charity would be enough.

Yes, I remember a comment on a thread here some time ago about how the "gene guys" at Monsanto, DuPont, etc. were going to work miracles and we would have 1000-, 5000- or 10,000-bu/acre corn to make corn ethanol and other genetic wonders. And I have heard claims that we could totally engineer our genetics to have chlorophyll in our skins so we could just make our food by lying around in the sun. That sounds like fun so I wish they would bring it on!

Inequality in the world will fall when the population drops from 1000 to 1. The fewer people the greater the equality and the lower the complexity. In the complexity resides the inequality.

Not only in complexity, but in the sheer numbers of the mass market. If you can make an iphone app that sells for $10 and ten million people buys it, then you can retire. The bigger the base, the higher the pyramid.

As the author notes, we have to be careful about faith.;-)

Personally, I find this article to be utterly convincing.

The only reason it doesn't scare the hell out of me is that my monkey brain time discount rate prevents me from actually being emotionally afraid of things still a decade away, or longer, in the future;after all, I will have been safely composted myself by the time the real energy crunch hits, when we are short of not only oil but also coal, natural gas , etc.

OFM, we will embalm you ;-)

Old Farmer would prefer the composting...it has a sort of natural poetry to it.

Anyway, my 4 grandperents had a total of 14 children. Of those 14, only my own father and mother had 4, all my aunts and uncles (city and country folk alike) had 3 or less, most had 2, all combined not quite getting to the total of 14. From my father and mothers children, myself and my 3 sisters have had a total of 3 children, and we are all past childbearing age. All my cousins have had 2 or less, with several having either none or one. In 2 generations, from my grandparents to mine, in about one century, we have cut our population growth to not only no growth, but to about half of what my grandparents generation was very used to. Our case is not exceptional, many of my school friends families had exactly the same or even more pronounced lack of population growth, in fact, population shrinkage. Similiar results are occurring in every nation passing into industrialism and then on to "post industrialism". At the rate we are going, what few offspring there are in the world in a couple of centuries will inherit a mostly empty planet...full of empty cities and abandoned buildings...much the way Gary IN or much of the old once crammed full but now empty industrial slums look today. They will have room to breathe thanks to one of the least energy consumptive but most revolutionary devices in history...the birth control pill and the human desire to be unencumbered by children.

And as old Farmer Mac says, I will be long composted by then...

RC

It was foretold:

Isaiah 24

How would new genes solve the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics. Most biological systems run at or near maximum efficiency anyway. LOL. The problem is that people require a lot of fossil energy to "live" today. Are you suggesting that genes could be engineered to reduce our need to burn fossils.

Maybe we could all pack into 1 square meter boxes with the right genes and live happily being fed mush from bacterial growth on seaweed.

I would say that this article is very important and shows that we are headed to steady state.

Would love to see a part 3, where we get an idea of what the steady state world will be. Can the US lead steady state or is Wall Street doomed to die an ugly death? When will the growth paradigm die?

I am sick of hearing about how China growth will save us. LOL. What a load of false logic.

A steady state world is an impossibility, because those trying to retain some sort of status quo will eventually be supplanted by those who grow. The growth meme is the one that will always succeed according to the laws of nature - produce overshoot, or die out.

The growth meme (as you call it) is nothing new for humans---but having petroleum products at our disposal to enagage willy nilly in the growth meme is relatively new. Without a lot of fossil fuels, the war-loving or exoansion-minded groups find themselves bogged down inthe realities of everyday existence....not that they can't win a few battles, or even take some territory but their hands are tied by thermodynamic laws. So a steady state world is going to look like the past, probably, with lots of localized skirmishes, lots of people who make efforts to grow but are forced to give up past a certain point. So the whole system is steady state but here and there you can see some groups dominating for a while. Those battles, or forays, or whatever you call it, would keep people busy and happy planning....Really it is nothing new, now we have global business, it amounts to the same thing (grow or die)---if and when it whithers due to lack of energy all those busy business people will not care much and look elsewhere for strategizing opportunities. People are such giddy creatures....

The problem is, the past never was steady state either.

Like a colleague of mine puts it: "By 2100, we'll all be living sustainably - one way or another".

We'll either solve this or we won't.

I agree. Growth will not say us. the opposite will. Since few in the world choose lower birth rates nature will take care of it with higher death rates. It is just we are usually afraid of the 4 horsemen. Since the west has not seen them for a generation we think they are not in the mix.

You missed the point. Most people hear about peak resources, and just say "science" will find a way. The entire point of this article was to debunk that argument. He does a great job of it.

If 2.3% growth continues, no matter how -- we boil the oceans in 400 years. So much for a "star trek" future ;)

A Star Trek future would cause the growth to move off of Earth and continue until we consume all the resources in the universe that we can access. If the universe is finite, then the day of reckoning would be delayed but not avoided. How long would be needed for humans to construct a Dyson Sphere around every star in the universe? Alas, we fanciful monkeys will not even construct one.

Who's Hawkings?

Surely, if we were to live in a Matrix style system, where everyone is effectively a brain in a jar, then this would massively reduce the need for energy consumption. After, all the cost of simulating a rich and energy intensive lifestyle would be little different from simulating a deprived and miserable one.

This doesn't really solve our immediate energy problem, but it does suggest a way in which an incredible standard of living could be achieved, without cooking the planet...

Only if applied toghether with some form of population control. The first article of the series was quite clear about that...

Tom, in Figure 1 what is the cause of the gradient change in GWP growth? Is this Bretton Woods (1945) and subsequent unilateral break from gold standard by USA (1971), following their peak oil event, setting the scene for deficit, monetary, bubble based growth that looks like is entering the end game?

It is just a fit to two straight lines, to describe a nearly straight line, while adding one slight wobble to improve the fit. A slightly curved parabola would probably also do. Or maybe an S-shaped curve: to my eye it looks like the growth in the most recent points is slightly lower again, more like earlier parts of the 20th century.

@Tom, Euan, Nichol,

The data behind the chart 1 above shows three distinct different paces of growth from 1900 to 1950, from 1951 to 1971, and from 1972 to 2000. It is likely that the 1950 switch has a lot to do with the end of world war II, rebuilding of the European economy speeding up, and the 1970 switch with the peak in US oil production and ensuing oil crises.

I have plotted the GDP growth figures to energy consumption from 1900 until 2000 (excluding biomass) which shows quite good correlation between energy consumption and GDP until 1970, after which the energy consumption pattern becomes much more erratic. Take care though that this is interpolated GDP data as the source provided by Tom only gives figures every 5 or 10 years (and the energy data as of 1970 is annually)

Rembrandt: Thanks for the significant analytical contribution! The tracking in some segments is stunning.

The tracking virtually disappeared after 1970. That's what's really stunning.

What is even more stunning is that some may interpret the erratic lack of tracking over the past few decades as some predictor of the future—against all physical reasoning.

That per-capita energy started saturating in industrialised countries around 1970 has profound implications, and there is no reason to expect that to change either, especially as more countries get saturated the same way.

Interesting point. Could you expand on what those implications are, in your view?

My sense is that the mantra of eternal growth had become systemic by the mid to late 70s and financing became a bigger part of the economy, so people could grow steadily through the drops in energy growth because they had enough borrowed money--which was ultimately based on the faith that net energy production growth would bounce back.

What we are starting to see is what happens when that faith is challenged. The top layers of the financial system--the investment banks--were hit first. Yes, they had gotten into some wild shenanigans, but those generally worked out (short term) average as long underlying energy growth kept bouncing back with enough demand (i.e. with high enough prices). But now with prices about ten times what they were in '98 and essentially no net growth in crude oil production since about late '03, the cracks in the system are starting to become more and more evident--the faith in the mantra is slowly being shaken to its root.

One might even call the idea that energy and economic growth are linked Faith!

.. I wonder if I've just committed left wing heresy?

We now have power through technology that believers once thought was the realm of the Gods. Well, congratulations, we've become God, and each one of us have to start being aware of our power and take responsibility for it. Most importantly that includes trying to discern what actually *is* in our power, and what is in the power of others.

.. Hopefully that is sufficiently heretical for the right wing as well..

Some charts I made in post Financial Return on energy Invested:

Energy Data from EIA link in previous post by this author, population from US Census, and real GDP in 2005 $ from USDA. GDP growth per capita is 1.34 % and population should level off at 10 billion in 2100 according to UN (medium fertility scenario). I don't want people to give up hope, but the transition to no growth still needs to happen, maybe just not in 100 years, but probably in 200.

Thanks for the graphs, Euan.

I'm confused about an apparent discrepancy between the last two graphs. Why, in the European one, is the energy efficient path toward the top while in the previous chart it was at the bottom?

Hello,

I believe that we are missing an important point. China has a energy intensive GDP, but they produce a lot of what we consume. Production is an energy intensive activity, so when they export goods to the USA or Europe, they export embeded energy (a iron garden table is somehow raw material + energy). When you pay 10$ for a chinese product, at least 75% stay in your country, so you increase your GDP without increasing much your energy need.

Best regards,

Esteban

Good point. And I think it is important to also put some of these figures in percapita terms.

The early 50s was when the Green Revolution kicked into high gear. All this new food enabled the population to take off. I believe this had no small part in GWP growth rate that took off at about the same time.

Ron P.

Its a good point Ron as one possible contributing factor. No doubt that population growth is one of the basic things that underpins GDP growth. This is one of the main reasons US growth has outstripped Europe for decades. But one cost of this is living beyond energy means resulting in deficit based finance.

Yes! We have been taking part in an Population Ponzi scheme.

I wish I knew a way to come down off this high we are on. I am afraid a crash is inevitible, and all of our talk is just an erudite effort at denial.

Facts are facts Once critical mass is attained, Uranium will undergo fission. Is this also a necessary result from some population cm? And, if so, what would you say that mass is, and what will be the ultimate impact?

In a word, is there a way to actually realize a sustainable steady state economy, or are we wasting time even considering it?

Serious times ahead. Maybe interesting, in the 'Chinese Proverbial' way, but serious.

Craig

Hard to say. Looking at history, most would say that there are few cases of large scale societies achieving steady state over long periods of time and many the overextended and imploded.

But human's are not uranium molecules. Supposedly there are things like cognition and culture that are malleable.

To some extent, it could be that to the extent we decide we can't change to adjust to these realities, we won't. In other words, any attempt to look at human society in a scientific way is bound to be like heisenberg (the principle, not the TOD poster) on steroids. Everything observation affects the subject being observed.

So, watch out for Heidinger's cat! The real problem is we really have never been here before, and prediction is difficult. Easy to look back and say, this is why that happened. Looking forward - not so much.

Underlying question: what do I tell my grandchildren? Other than, "Sorry!" that is.

Craig

"In a word, is there a way to actually realize a sustainable steady state economy"

A very good question. I think that if there is a way to realize a sustainable steady state, it will involve a revolutionary break through in economic theory. All rational thinking in economics now involves the core assumption that the goal of economics is to guide thinking about how to maintain 'healthy growth'. Tom argues that:

1. Sustained growth in energy consumption is not possible.

2. Economic activity cannot be entirely decoupled from energy consumption.

Taken together, it follows that sustained economic growth is impossible.

My thought is that we don't have any economists thinking about how a constant size economy might work. Maybe if they thought about it carefully ... maybe they might get some good ideas as to how to reorganize and act.

This is not a proof that anything good has to follow from more careful thinking, just a thought for further investigation.

Economists are very optimistic about technology coming to the rescue.

But this optimism is based on absolute ignorance of technological and scientific fact. No. Economics is not science. At best it is a coherent belief system, like Islam or Christianity, but with a much cruder moral code than either.

What economists know as 'fact' about technology is not fact but is stories told them by hucksters pedaling investment 'opportunities'.

"if there is a way to realize a sustainable steady state, it will involve a revolutionary break through in economic theory. All rational thinking in economics now involves the core assumption that the goal of economics is to guide thinking about how to maintain 'healthy growth'."

You should learn some economics, this is just embarassingly silly.

I have met or heard of very few economists who don't think that eternal economic growth is possible, necessary and a kind of absolute good. Is your experience different? Most economists still, asfaics, still accept growth as an unquestionable axiom of their faith.

But this part of his/her post did reveal some ignorance:

"we don't have any economists thinking about how a constant size economy might work"

S/He apparently has not heard of Herman Daly and others that have further developed his ideas, in spit of there having been main posts here about his work. But these do seem to be exceptions to the rule, in my experience.

But perhaps there are vast numbers of economists working on steady state economics that I am unaware of, beyond the relatively tiny (as far as I know) but interesting 'de-growth' movement.

"I have met or heard of very few economists who don't think that eternal economic growth is possible, necessary and a kind of absolute good."

I have heard of very few economists who don't believe in pink unicorns. Actually, I have heard no-one say that they don't. No a single one! Could it be the same with you? You expect them to believe in eternal economic growth and assume they do if you don't hear them say otherwise?

"Most economists still, asfaics, still accept growth as an unquestionable axiom of their faith."

Then just how do you see this?

"But perhaps there are vast numbers of economists working on steady state economics"

You came closest to the truth above when you said that about "absolute good". So, if economists generally (1) think growth is good, (2)don't see any near-term end to growth and (3)don't believe the system will be unable to handle no growth, then there is no point in working on steady state economics, right?

The above economist position comes from a NYT Econo-blog post mentioned elsewhere on TOD.

What I don't get is what kinds of twirly bird thoughts fly through the echo-chamber brains of most economists.

Do they imagine that there are these mythical "job creators" out there?

And all we've got to do is take a cattle prod labeled as "aggregate demand" and put it to the back sides of these so-called "job creators"?

And that will fix everything?

Which aisle at Home Depot do I search to get me one of them "aggregate demand" prods?

[ i.mage.+]

________________________

[i]= image, [+]= more info

"You expect them to believe in eternal economic growth and assume they do if you don't hear them say otherwise?"

No, I make a point of asking them specifically.

If find your final point incomprehensible.

No matter what some or most economists think, it is still of course always worthwhile for someone at least to work on steady state economics. So your last paragraph seems to be a non-sequitur, at best.

I honestly want you to enlighten me, if you know of vast numbers of economists working on steady state economics. It would really make my day and change my view of the whole discipline.

So please do tell me if you know of any, especially if they represent a large part of the field or a major movement.

"No, I make a point of asking them specifically."

Really? Care to name drop?

"No matter what some or most economists think, it is still of course always worthwhile for someone at least to work on steady state economics. So your last paragraph seems to be a non-sequitur, at best."

Yes, you think it would be worthwhile, but I tried to explain why economists doesn't think so. I don't get why that would be non-sequitur.

"I honestly want you to enlighten me, if you know of vast numbers of economists working on steady state economics."

I'm quite sure very few do. I explained the reason why that is so.

"S/He apparently has not heard of Herman Daly "

But I have heard of Herman E. Daly. AFAICT, his writings are ignored by both fresh water and salt water economists. Both schools are busy currying favor with the rich. Like Tom Murphy, Daly has written good pieces on how continued growth is impossible. ( different starting context and chain of reasoning. same conclusion. ) But neither has addressed what must change in our financial system in order to actually transition deliberately from the here and now to the promised land. Or have I missed something? Please show me.

There was a nice piece by Daly on a stepwise plan to transition to steady state on some website that may be familiar to this readership: http://www.theoildrum.com/node/3941. It was good to see a carefully thought-out plan, but I was struck by the sense that none of the steps would be enacted unless society's goal was to deliberately transition to steady state.

I wonder how much of past economic growth was just dependent on population growth, and how slowing end ending population growth would affect economic growth. With a growing population, it is rational for a current generation to take on large debt, to be payed off by the larger future generation, that will profit from the investments made using those debts.

I can remember when GDP used to be reported as 'per capita'. And people were only supposed to be happy if this per capita number increased - which would indicate real raising of wealth/living standards.

Sometime in the early 90s (if memory serves) the 'per capita' was mysteriously dropped and it was just the aggregate GDP in the whole economy that was reported.

Another sign of what Chris Martenson calls 'fuzzy numbers'

Tom, politicians can be informed that exponential growth of economy, energy use and population must stop one day but knowing when that day actually arrives is really quite important. Whilst accepting your broad arguments on energy efficiency gains, I believe that massive gains are still there to be had. For example, wind produced electricity is extremely efficient in energy terms and charging a car battery from this source can provide vehicular transport that is 2 to 3 times more efficient than ICE. Add to that legislation that penalises single occupancy journeys and so forth then i think the possibility exists for even larger gains - that of course cannot go on for ever. Similar argument may apply to heat pumps powered by wind or solar sources linked to pumped storage.

On the other side of the coin, replacing extreme high ERoEI energy stores with lower intermittent flows places a large burden on the system.

As I commented in your last post, I believe that the Human - Earth system response to boundaries and limits will be incremental. One of the first things to be hit will be pensions and social services (social security, education and healthcare) - it is already happening, but just that society's view is that the cause is banking and debt miss management.

Part of the system response is for population to stabalise and the growth rate is already slowing. How the population knows to do this is of course intriguing - pressing on limits.

My main point is this. If efficiency gains and incremental change enables the current system to hobble along for another 50 years or so then that is what I think will happen. Virtually zero chance of OECD and BRIC deciding to adopt a new model now based on the unflawed logic of the eventual and ultimate need to change. Of course political hands may be forced by events and at that point having good understanding of the underlying causes of stagnation and economic depression would be good to have so that a more sustainable system can be designed to replace the current one.

Euan: Yes, our lack of ability to predict a year when economic growth will stop reduces any chance of deliberate, pre-meditated action. Even if we could put a definitive, convincing number on it, anything beyond 5 or 10 years may not inspire action. So I agree that the actual path will be to muddle along until we can't any more. Of course this path poses significant risk: making a transition away from the growth-based economy in crisis-mode may be ugly. But even if this is our fate, I see a role for universal awareness that growth is fated to end eventually. As you suggest, understanding the underlying cause of stagnation will be handy in a pinch.

Slightly facetiously, this is a bit like trying to predict one's (or someone else) last breath. Wrong everytime until overtaken by the event.

"transition", "crisis"... Don't those words have the same meaning?

Why would anyone expect or even WANT a political solution to over population? Even small groups of people are ungovernable and resent being controlled. The world will never have a useful overall leadership. It's too diverse. Too many cats to herd.

The markets will fix this in due time. Rising resource prices will naturally curb growth. No need to fear the future. It will fix itself.

The 'markets' are what got us into this mess. I am not optimistic that the cause of the problem will be a very good solution to it.

Some may say the markets accelerate resource consumption. Offshoring energy intensive production to China did nothing to reduce the consumption of resources. There are no market solutions to resource limitation in a debt-based society other than to impoverish future citizens, which is what we are presently working towards (i.e. read the front page of the newspapers).

How long can you raid the future my friend with your markets?

It seems to be a common misconception here that debt is about lending from the future. It isn't, you always borrow from the present.

Markets doesn't accelerate resource consumption as much as it optimize the utility of available resources. Given resource constraints, markets are the way to go to make the best of what we got.

Hence, Social Security and most pension funds are currently being raided. CO2 deposition into the atmosphere. Cheap fossil stores are eliminated using ever more energy units per returned energy units.

Sounds like the future is being raided.

"Markets doesn't accelerate resource consumption as much as it optimize the utility of available resources. "

To my mind this statement is nonsense that illustrates something of the nature of the problem. To say that something optimizes something else without having a clear idea of what that something else is -- is foolish. I suggest that the easy way to make the statement very believable is to say that utility is growth, in the population and in per-capita consumption. But isn't that the rat race from which we must escape?

I don't have any crazy alternative to crazy growth economics. I just don't believe conventional wisdom has much to offer.

A crazy thought for your consideration: If gold were bid up to about $500,000

per troy-oz, by the gold bugs, the US government could pay off its debt in one grand stroke by selling its gold holdings and buying back its outstanding treasury notes.

I'd like to give an answer, but I don't know where to start. What you wrote just don't make sense. The utility is defined by you and me, all that is acting on the market, having preferences in consumption and life style.

But how can the markets optimize both your concept of utility and mine simultaneously?

You should not attribute to me a shared belief in your definition of utility and optimum, which you have not defined. That really does NOT make sense! Or perhaps it makes sense, but only to a madman. IMHO, you are offering a muddled version of conventional wisdom.

The problem that is central to the existence of TOD is the advent of a gigantic decrease in availability of an important 'available resource', namely petroleum. Many people here are skeptical of the belief that the market optimum utility of the available resources, with petroleum no longer so plentiful, will not provide for the continuation of civilization as we know it today. Your assertions offer them little comfort.

"But how can the markets optimize both your concept of utility and mine simultaneously?"

By adapting to what I demand, and by adapting to what you demand. This is one reason markets are so great.

"Many people here are skeptical of the belief that the market optimum utility of the available resources,"

Sure, but they should not be skeptical. It is the best way. Neither planning nor rationing can do a better job.

"The utility is defined by you and me" is what you said. I took that to mean that we agree on the definition of utility, which I found highly implausible for a starting assumption. Now you are indicating that what is optimized is some melding of your desires and mine into a single composite desire. But without any idea how this melding is to be done. It boggles my mind to think how you can test such an hypothesis, or claim that it has been proven.

" It is the best way. "

This really does smack of a belief system like Islam or Christianity, only much more shallow. Where is the observational support? Listen to yourself.

The way things are being done now seems not to be working very well for many people. You appear to be taking a position that was parodied in Voltaire's Dr. Pangloss. Do you really intend that?

"Now you are indicating that what is optimized is some melding of your desires and mine into a single composite desire. But without any idea how this melding is to be done. It boggles my mind to think how you can test such an hypothesis, or claim that it has been proven."

Melding into a single composite desire? Again, you don't make sense. Perhaps I expressed myself a bit too tersely, but I was convinced that readers would know enough of the world to get what I was talking about. I'm sorry, I simply won't try to explain to you how grassroots' demand is aggregated and supplied efficiently in the market place. It is too basic.

"This really does smack of a belief system like Islam or Christianity, only much more shallow. Where is the observational support?"

Is this candid camera or something?

"The way things are being done now seems not to be working very well for many people. You appear to be taking a position that was parodied in Voltaire's Dr. Pangloss."

No, we don't live in the best of worlds. It is far too statist.

I don't think a more sustainable system can or will be designed...it will be the outcome, an unintentinal one, of a more local economy. People will simply stop havingthe ability to build dams, bridges, highways, factories, etc. They will just make do with what is around and stop noticing what is happening far away because of constraints of paper and electricity costs. Little by little large empty abandoned buildings will be seen as potential sites for new farms or other more sun-based economic activities. LArge governments will whither and then all of their important activities will be curtailed...It is a scary future because of the nuclear power plants that need constant tender care. People will simply shrug...ah well, it had to be this way....infinite growth was an unrealistic dream.

Tom,

This would mean that an increasingly small fraction of economic activity would depend heavily on energy, so that food production, manufacturing, transportation, etc. would be relegated to economic insignificance. Activities like selling and buying existing houses, financial transactions, innovations (including new ways to move money around), fashion, and psychotherapy will be effectively all that’s left. Consequently, the price of food, energy, and manufacturing would drop to negligible levels relative to the fluffy stuff. And is this realistic—that a vital resource at its physical limit gets arbitrarily cheap? Bizarre.

(1)Why are you assuming that the price of food, energy and manufacturing will not increase in price relative to service sector?

For example if these items were X10 more expensive in you projection to 2100, they would account for 20% of economy rather than 2%(about what they are now).

(2) You are using a very narrow definition of services; what about entertainment(movies, internet),is there a limit to value of what can be spent on restraunt meals(same amount of food, compare one star with five star). What about medical services? or software? or improved education? surely these are not "fluffy stuff" but real valuable services worth paying an ever increasing portion of GDP to access.

I would agree that growth in financial services or doing each others washing are "fluffy" .

@Tom, Neil1947

The growth in financial services, entertainment, restaurant meals, washing in today's society are not fluffy in an energy sense these are quite costly activities. Unless you are referring to an economy were all these things are done solely by hand (which means a huge drop in income). In our society washing is done by complicated energy consuming machines, financial services require vast electronic and digital infrastructure (the energy cost to produce a laptop or computer is substantial), the production of a movie involves hundreds of people, lots of equipment, tens to hundreds of flights, the production of restaurant meals is tied into the global interconnected system. The bottom line is that there is no such thing as an unphysical economy possible. The only thing that would come close is a lifestyle were we go back to a manual labour economy with far less of the wealth we have today as substantially more human labour is necessary to create an "unphysical" economy.

Rembrandt,

I was drawing attention to the range in quality and thus value of say a $10 fast food meal or a $200 fine restaurant meal, similar basic food inputs, or a movie grossing $500 million is only going to require a fraction of the energy of $500 million spend on driving a million low mpg SUV's an extra 1000 miles.

In general the service economy is less energy intensive( tourism being an exception) than manufacturing, oil refining, mining. If the energy intensive parts of the economy become relatively more expensive more of the economy will be dominated by lower energy and resource intensive service sectors. This shift can be very slow and still have growth in GDP and no growth in energy consumption.

@Neil1947

"In general the service economy is less energy intensive( tourism being an exception) than manufacturing, oil refining, mining. If the energy intensive parts of the economy become relatively more expensive more of the economy will be dominated by lower energy and resource intensive service sectors."

That I agree with, however you assume that the service economy can do without the manufacturing, oil refining, and mining sector. It relies on it to function. The idea that we can shrink the manufacturing, oil refining, and mining sector and increase the service sector is a fallacy.

Rembrandt,

The idea that we can shrink the manufacturing, oil refining, and mining sector and increase the service sector is a fallacy.

Even though the services sector relies on the energy, mining and manufacturing sector there is no intrinsic ratio, as the energy intensity of the economy decreases, the energy sector may account for a smaller portion or energy may become more expensive as FF use is replaced by more expensive renewable energy. Mining could decline in absolute production (tonnes/year) as % recycling increases and still have growth in absolute consumption(tonnes/year). Manufacturing value could continue to grow(even if at a slower rate than GDP) but consume lower amounts of materials and energy by producing more high value products( for example an Chevy volt rather than a Chevy pickup).

I don't see a limit to services increasing, although there would be a minimum of manufacturing required/capita just to maintain basic needs(food, water housing, transportation) so mining, energy and manufacturing would not necessarily shrink in absolute terms(KWh of energy or tonnes of goods) even if they didnt increase or increased at a very modest rate.

I think Neil1947 is on to something that most of the rest of the comments are missing. Try to think about the idealized world that the original post envisioned: energy inputs approaching a fixed limit but non-energy using aspects of the economy continuing to grow. It seems to me very unlikely that the value of the energy intensive parts of the economy would go to zero. Instead there would be inflation in the cost of these parts to keep demand in check. If growth of non-energy intensive parts was still possible with fixed energy input, then you would indeed have growth in a system with fixed resources. Note that it is likely impossible to grow non-energy intensive parts indefinitely, but that is not under discussion. That is an assumption of the model in the original post. And I think this argument in the original post is wrong. You can't show that exponential growth is impossible in an economy with fixed inputs without showing that no parts of the economy can be fully decoupled from the inputs.

We all need to eat, drink, sleep and socialise. (and some other basic functions). We need education, medical care, and we need a social backup system, to help when our house catches fire.

Beyond that, we need entertaining to stop us going stir crazy, and we need a belief system to help us make sense of the world, and to give ourselves some self-respect. Some of us manage to carve out our own, most of us select, or are indoctrinated into, a pre-existing one.

All these needs require energy and resources. Some are absolute. We all need enough clean water and food to keep us alive and healthy. How much we spend on a belief system or entertainment, is highly variable.

The US system is hopelessly inefficient in providing all of these functions, except basic food and water. The US has never needed to be efficient because it had resources to burn. Unfortunately, it evolved a belief system that included profligate consumption of resources as both a right and necessity. This was most unfortunate and is unsustainable.

The OECD has used cheap energy to build a huge material and social infrastructure which support a high quality supply of all these requirements (except self-respect). This infrastructure has increased efficiency and quality on the large scale, but it has a high operating cost in energy and resources, and will require an even higher cost in maintaining and upgrading this infrastructure. We are hitting the law of diminishing returns, and we have lost resilience. the system cannot be maintained in its entirety and it will not degrade gracefully.

The irony is that we can have a long, healthy and fulfilling life on a far lower energy and resource input, and plenty of evidence that the GDP required is well below $20,000 per capita. Unfortunately, there is no easy way to redesign our infrastructure or culture around this lower figure. We cannot easily transition without collapse.

With 7 billion people, even $20,000 is probably unsustainable worldwide. The point is academic because we are degrading our biosphere so rapidly already that we could never transition quickly enough.

There is no well defined or universally accepted metric for monitoring these basic quality of life requirements, although there are many attempts. We urgently need to redesign global society around one of them, all of them would be an improvement over what we have now.

Exceptionally well stated RalphW.

Indeed. Especially:

"The US system is hopelessly inefficient in providing all of these functions, except basic food and water. The US has never needed to be efficient because it had resources to burn. Unfortunately, it evolved a belief system that included profligate consumption of resources as both a right and necessity. This was most unfortunate and is unsustainable."

And of course, beyond the logistic difficulty/impossibility of scaling down the economy and society, there is the political difficulty/impossibility that a very powerful Republican party is rabidly against anything remotely suggesting such a thing, and most Dems are not too far behind them. Other parties are so minor as to be irrelevant, and most of them are as a bad as or worse than the major parties on these fronts.

We should, though, recall that monastic life sustained bodies and souls for many for thousands of years on much less than the modern equivalent of $20,000 (or even $1000?). That is why it seems to me that something like a mass immediate religious conversion of some sort is the only thing that has a chance of even slowing down our spiral into becoming an essentially dead planet.

A former oil market analysis and peak oil follower writes this blog :

http://oscfreeland.wordpress.com/

Yes very true. One thing not often mentioned in consideration of a powered down economy and the (for me) fear of a brutish/dangerous dumbed down society is the wonder of instant communication and transfer of ideas via the internet, email etc; TOD a prime example. We can be linked, can learn, discover, entertain, and share without using too much energy.

However, getting from here to there for many stuck on the inside of the ship going down will not be pretty.

"We urgently need to redesign global society around one of them, all of them would be an improvement over what we have now."

And yet the turkeys cannot move forward on debt ceiling vote, the banking crisis, and the rape of economies by a few powerful individuals and organizations.

This excellent article gives creedence to the idea that one best get building that personal lifeboat and hope it floats.

All the best....Paulo

Well said. Diminishing marginal returns on investment, sunk costs etc. The pieces of the puzzle are starting to come together.

We will become poorer, whether by deflation or inflation is fairly irrelevant. Life will get down to the essentials, which will take up all of the remaining cash flow even as everything else is liquidated. Permanent joblessness, with the remaining jobs becoming less exciting and less lucrative. Endless political and financial instability as the decline continues. Maybe a drought here, a famine there, a war over yonder.

What can stop this? The energy isn't there. Krugman the debt pimp is welcome to go back to school, get a degree in physics, and try to make nuclear fusion work.

Rembrandt: thanks for making this point. I am completely with you that none of our activities can be totally decoupled from energy. This only makes the point stronger that capped energy growth translates to capped economic growth. In the post, I entertained the economist's fantasy that perfect decoupling is allowable, and showed that even then growth has limits (if energy has any cost at all). It sounds like you don't believe in this fantasy any more than I do.

@Neil1947:

For point 1, I think its ridiculous that food, energy, etc. would sink to arbitrarily low prices. But I'm saying that this would have to happen in order to see unabated economic growth: once the physical system is tapped-out/level (if we are lucky enough not to see decline, that is), then the only way to continue economic growth is through the "fluffy" stuff—meaning that the relative price of food/energy/etc. would have to drop. I think this goes against simple supply/demand, which only reinforces my point that the fluffy stuff can't grow without bound, and therefore economic growth is capped.

For point 2, I'm happy to add any services you like. I just didn't want an exhaustive laundry list weighing down the paragraph. And I don't discount their value to us, or their ability to grow to a larger fraction of total economic activity than we see today. I just think these things can't grow to 99.99999% of economic activity (and beyond), which is required to keep the growth dream alive indefinitely.

I applaud your physics insight, but I think your economics is a little sketchy. It is emphatically not true that the price of a resource depends on its share in the world economy. Case in point: platinum. Platinum mining and processing is a negligible fraction of economic activity, but we can't do without it: it's indispensable for catalytic converters in automobiles and chemical plants. And yet it's very expensive, and hasn't gotten cheaper over time.

But platinum has always been a tiny part of the economy. So let's consider horses. In the mid-19th century, horses drove the Western economy, and a decent horse cost in the ballpark of $50. Today, they're a nearly irrelevant sideline to our economy, and cost around $1500 --- a factor of 30 price increase. On a consumer price index-adjusted basis, the price of a horse is the same as it was 150 years ago.

You're absolutely right that, come what may, everyone has got to eat, including the farmers. (I'm using "farmers" as a proxy for everyone who produces goods in the "physical" economy) But that doesn't place any limit on the price of food, or its share in the economy. Why not? Because in an expanding service economy, each member of society spends more and more money on things that aren't food -- INCLUDING THE FARMERS. For the last 200 years, farmers have spent less and less of the products of their labor on feeding themselves, and more and more on machinery, fertilizer, technical expertise, and luxuries. As farming has gone from the majority of our economic output to a small minority, the *number* of farmers has shrunk dramatically, but their food output has increased.

Consider the absolute limit of a future world with only one farmer. He controls a robotic fleet of planting, harvesting, and transporting machines, and pays many billions of dollars a year to people in other market sectors: robot machinery vendors (who employ thousands of skilled engineers and shopworkers), repair mechanics, weather forecasting agencies, crop planning consultants, industrial architects, etc., while his family ingests a steady diet of blockbuster movies and video games. Running all this is expensive, so his food doesn't come cheap; he's a negligible part of the economy, and yet food still costs money, and everyone still gets fed.

I think the way forward is to focus on the physics wherever possible: money is slippery and vague stuff, but energy is always conserved.

If there's going to be one farmer, it's going to be me. But the family diet will be more along the lines of the latest supercomputers, Terabit network access, and college tuition/room/board grants for up-and-coming game programmers. Or maybe video feeds from private space exploration.

goodmanj: I don't deny that the nature of farming has changed over time so that fewer farmers produce more food. We still spend 17% of our energy in the U.S. on food production. Some of that is shifted into manufacture of gigantic farm equipment, for instance, that allows one farmer to do more. A significant portion of the economic pie also goes to Monsanto, ADM, Cargill, etc. to control the genetically modified seed supply. So while farmers themselves are being squeezed to lower levels, I think you'll find most Americans paying 10–20% of their incomes on food (more in Europe, and perhaps most of income in impoverished places).

I very much doubt that we'll ever consider food to be an insignificant part of our economy—especially as population pressures, overtaxed lands, and climate change-induced crop failures create food shortages. As you concede, platinum is not a good example. Horses aren't either since we replaced them with cars and spend much more on this mode of transport than we ever did on horses (cars are more expensive than the inflation-adjusted horse price, and at least as ubiquitous). What do we replace food with? Food?

Finally, I'll just say that if you're really willing to envision a future where one (or a few) "farmer(s)" control a robotic, automated fleet of farm machines, then we do have to part company and may not see eye to eye on a number of issues. We have not proven that we can do anything of the sort. If this is the corner we must paint ourselves into to support endless economic growth, then I think it only highlights the absurdity of the notion.

We still spend 17% of our energy in the U.S. on food production.

Well, no. We spend that much on food related things, but the inputs are very different. In particular, the single largest item is refrigeration in the home of consumers.

I think you'll find most Americans paying 10–20% of their incomes on food

Sure, but the food is very different. If Americans still cooked their own food, that would require about 2% of their income. Instead, Americans consume the majority of their food through restaurants (including fast food restaurants), and the majority of the remainder is heavily processed. This is far more convenient, if not necessarily higher nutrition...

cars are more expensive than the inflation-adjusted horse price

Cars are far less expensive to buy, adjusted for horse-power, or any other measure of utility you might want. They have far lower operating costs, and last far longer.

One book that I enjoyed the hell out of a couple years ago was Steel Beach by John Varley. And this was the whole premise of it (and of all the stories he wrote in that setting). Given enough (magical) energy and a complex enough (fantastical) manager to support a population, and tapped at efficiency, he imagined humanity sinking pretty deep into frivolity, occupying itself with entertainment and tourism, and generally constructing stories out of the character types that struggle for meaning in an advanced, brave new world sort of steady state of civilization. I've always found his writing to be an astute balance of basic understandings of thermodynamic limits, complexity, and human nature, extrapolated however ludicrously far.

See also the Culture novels of Iain M. Banks. Banks's specialty is finding meaningful conflicts to support plotlines in a post-scarcity society. (His other specialty is the Really Big Thing.)

I think the Culture is one of the most convincing post-scarcisty utopias from the socio-psychological point of view. Unfortunately, Banks not only needs post-scarcity for this to happen, but also superhuman AI.

@Tom

Thanks for the post, the points about efficiency and the difficulty of substitution are especially important. The efficiency gains in industrial societies these are fairly low unfortunately, except from a user perspective which is too little recognized by governments and business.

One topic I would like to see addressed is what population level, given our current level of technology, can we expect the earth to consider sustainable (carrying capacity).

Currently, we are drawing deeply down into our resource reserves and if we just stopped now and held our energy limit, we would still soon bump up against other resources like:

arable land

clean air

low CO2 air

sustaining forests

sustaining ocean fisheries

sustainable amounts of mined products (using a combination of mining and recycling)

Thus, if we put the two subjects together we soon see that not only must we stop growing, but ride the decline to sustainability. Anyone else feel uneasy about this? It strikes me like a reverse roller coaster - fun on the way up but depressing on the way back.

Yair...I see this "arable land" limitation all the time. What is arable land? If it is land that can produce food there is no shortage here in Queensland.

There are millions of acres of country in forty inch plus rainfall regions right up the eastern seaboard. If it was in China or Indonesia the whole region would be farmed...right now it's running Brahmans at about one beast to nine acres.

Now a question to economists: which steps should governments take to ease into the necessary transition into an economy that in the future might need to have quite different underpinnings. A stable non-growth economy, with stable or even falling population numbers, probably needs to depend less on debt. Unless the debt is inflated away, which seems to be the way that structural change of economies often works .. ?

Would targeted stimulation and investment in future-directed business help? Or is the current craze of austerity what we need to force a large part of the population into a different state of mind, and reduce consumption? Or is a combination of austerity and stimulation needed?

Regarding steady-state economies, I have no faith that such can exist, unless the system greatly reduces the use of debt. Even then, to be steady state for the long term, they essentially have to do without fossil fuels. To me, they sound pretty much equivalent to post-crash scenarios in which we move to an economy where our only food is that that we grow ourselves with hoes and perhaps farm animals, and we dig our own wells with shovels.

I read through the 1972 version of Limits to Growth. The authors hypothesized some sort of steady state economy that lasted only until 2100, by dropping fuel use way back, and assuming that it could be used in a level fashion (perhaps with a lot of nuclear energy) over the approximately 125 years in question. (Then fuel use went to 0!) They also would control population to remain level. I don't think this type of temporary steady state is really an option. For one thing, our current financial system would not withstand the huge drop in production needed to negotiate the step-down in energy use required for this to occur. It is also doubtful that we could support the world's population on a tiny fraction of today's fossil fuel use.

"our current financial system would not withstand..."

Maybe you haven't noticed, but our current financial system is imploding in any case--time to find a new system.

And note that it is only a tiny fraction of the world's population that uses the lion's share of the ff's.

As a shameless plus I would like to present a paper I have written about almost the same topic.

http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2007arXiv0711.1777D

Yvan,

The abstract looks interesting, but I can't figure out how to get a copy of the paper. Do you have a link to instructions?

Click on arXiv e-print (arXiv:0711.1777)

Then click on Download PDF and you'll get the paper

A few very basic criticisms:

1. Per-capita economic growth has been decoupled from energy the last 40 years in industrialised countries (like the US, UK, Germany...). For them, only the part of growth that is dependent on population increase leads to an increase in the energy consumption.

2. That our economic system needs growth is simply incorrect. I have raised the point before on TOD, and nobody has been able to defend the idea that investments, loans, interest and so on would depend on growth. They do not!

3. Economic growth may stop one day, but it may very well be so far off that it would be purely sci-fi to speculate about what the world will be like then. For instance, revolutionary genetic reengineering of humans may be part of the mix.

In short, the focus on growth (of either kind) is unwarranted, and these articles are a bit like straw men. We need growth for poorer countries, to industrialise them and get their populations to peak. The rest of the chips may fall as they will, and the invisible hand can and should be allowed to sort it out for us.