A few more transit stats

Posted by Stuart Staniford on December 15, 2006 - 10:11am

- The Department of Transport transit infrastructure spending numbers I found were off by an order of magnitude, included vehicles, or were otherwise wrong.

- My statistics were old (around 2000), and it was All Different Now, because ridership was up following the increase in energy costs.

- It would be Even More All Different after peak oil, when transit would magically become Much More Effective in the US than it seemingly was hitherto.

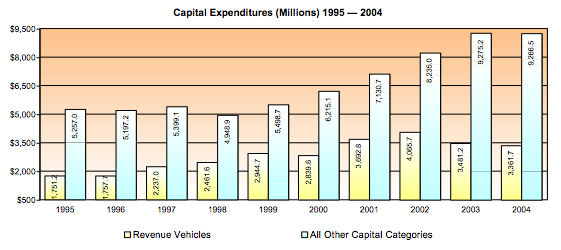

These guys see capex on infrastructure as a little less than $10b/yr, and rolling stock as $3-4b/yr. Their numbers are not consistent with the BEA derived numbers the other day, but are in the same ballpark. Transit spending has been increasing sharply.

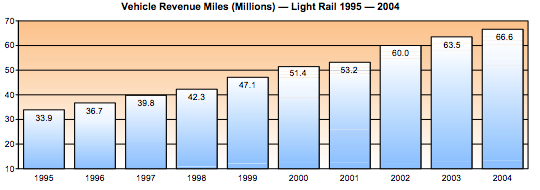

This has increased capacity in just about all forms of transit. For example, the total amount of light rail service available roughly doubled in the decade 1995-2004.

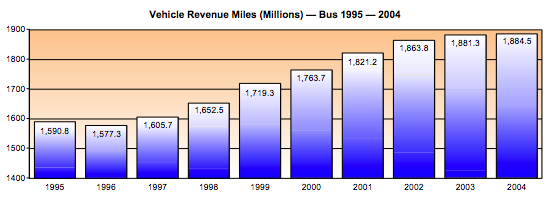

Bus service went up by a more modest 18% or so.

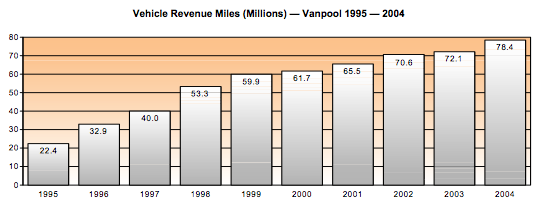

Available vanpool service more than tripled:

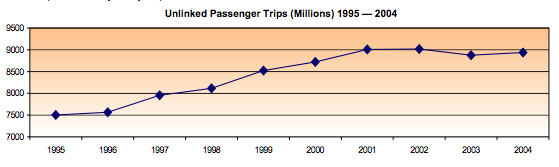

In response to all this increase in capacity, total passenger trips increased 19% over the decade.

Light rail for example, where available service miles went up 100%, saw an increase in passenger trips of 40%.

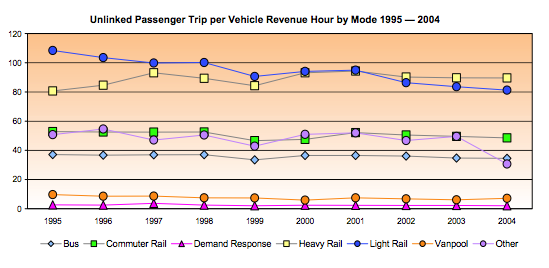

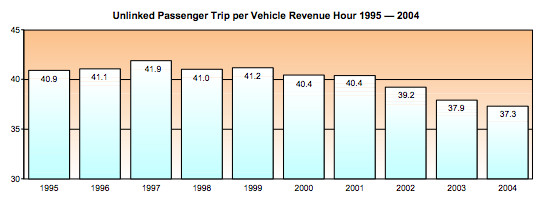

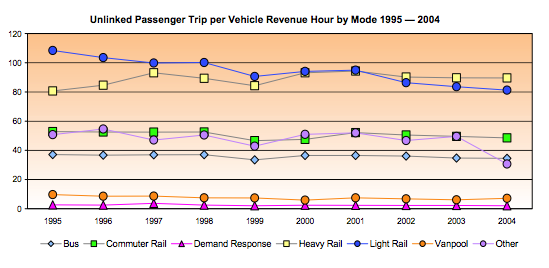

So that must mean that ridership is growing slower than the increase in capacity, right? Yup:

If we breakdown this number (the passenger trips per hour of service provided), we find that the utilization is dropping in most modes. It's particularly serious in light rail, but nothing is doing much better than holding it's own. The best is perhaps heavy rail (but that may be in part because heavy rail service increased less than others - only 20% or so).

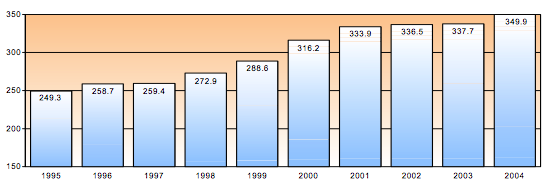

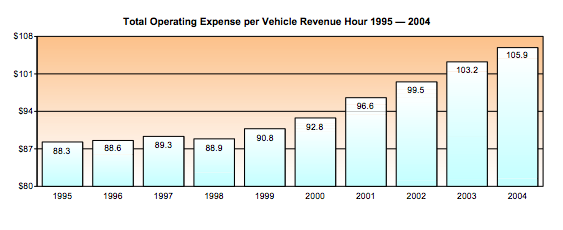

Operating costs per trip started climbing about five or six years ago. I assume this is mainly due to the increase in fuel prices.

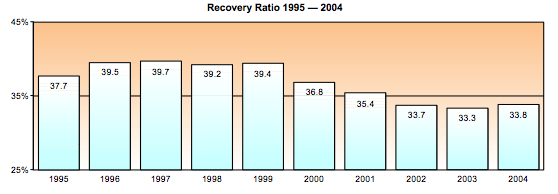

With costs per hour of service going up, and ridership per hour of service going down, the amount of operating costs covered by fares, never good, is falling:

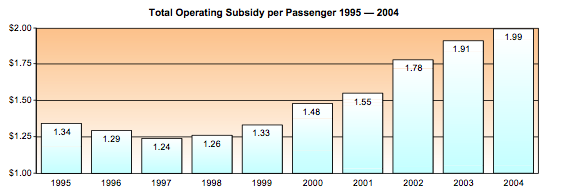

Thus the operating subsidy per passenger is going through the roof (and this doesn't include costs of capital):

So, in summary, during this pre-peak run-up in energy prices, we invested more and more heavily in transit. The effect of that was to increase capacity, but lower utilization. Operating expenses increased, and thus the overall financial performance of transit systems degraded significantly, requiring much larger subsidies per passenger (and the number of passengers increased). Overall, we got diminishing returns from this strategy suggesting that the best transit opportunities are already in use, and newer ones are more marginal. Light rail seemed to degrade the worst of any of the modes.

Under the assumption that the post peak-oil period involves still further rises in energy prices, if we invest even more heavily in transit, it would appear to me that we are likely to get even more diminishing returns.

Very interesting graphs, thank you. They in fact spell a bitter tendency because they encompass years of higher energy prices, where people unfortunately didn't abandon private transport for mass transit.

But again you use the single Liberal view point where mass-transit is private and gets subsidies from the State to penetrate the market. And you continue to compare mass-transit to private transportation on that basis - which is ill formulated because it will always cost more to the State. I don't think that Liberalism will ever suit politics towards mass-transit.

Finally you can't possibly assume that in a post peak environment people won't use mass-transit because they aren't using it now. American folk still have wages above most of the countries' folk, and in fact can still afford for expensive private means of transportation. When (if) they loose that capacity they'll have to use mass-transit.

Here is the short list of places where mass transit systems work:

- Cities which have too few parking lots to accomodate commuter cars, e.g. New York, London, Tokio. You can drive in but then you have to drive your car back home because there is no place to stop.

- Cities which levy 100% luxury tax on cars and gas, e.g. Singapore.

- Cities which have too few parking lots and levy a 100% luxury tax on cars and gas. That would be Singapore.

Everywhere else in the world mass transit is an addition to automotive transportation, not its replacement.It is refreshing to see thought that once in a while someone shows up who just don't get it and still tries to make it a political matter. It is not. Mass transit is simply a matter of urban design. Some urban planners get a fighting chance to implement working mass transit systems and most don't. It does not matter how many billions of dollars get spent on a system. If it is in the wrong place, it will fail.

Now... that does not mean there should be none in places where they fail. There should be. They are simply a public service to those who can not or do not want to keep a car. Availability of cheap public transportation is simply a matter of quality of life. And quality of life, again, is independent of political affiliation. If a town sucks, it sucks for both, liberals and conservatives.

Not in Bulgaria and most of Easter Europe AFAIK. Living there gives the distinct feeling that the various forms of mass transit are the primary mode of transportation, while personal cars are considered a luxury (as opposed to necessity) and are accordingly taxed. It is the design of the cities (compact, walkable) which is guiding this policy as well as the cost of energy which has always been high. The mass transit is truly mass - meaning that the majority of the population is using it for most of the trips.

Personally I never missed having a car over there. Having seen both extremes (currently in suburban Atlanta) I can say that if I could choose it will be somewhere in the middle - which is to a great extent achieved in West european countries. I would love if I could take the train to work here and have some free time while travelling instead of being stuck in congestions and risking my life on the highway. I would have still kept the car of course for leisure trips or shopping.

My grandparents owned one automobile, as did my parents until the mid 1960s.I rode city busses to schoole until my graduation from High School.

Cars are fantasticially expensive. Depreciation, fuel, insurance, extra expense for driveways and inside parking, maintaince-I bet if we add it all up then the IRS 0.445 cents per mile deduction looks too low. Thats $5,000 or $6,000 a year for most automobiles and even more for luxery cars like Hummers or $60,000 dually pickups.

We subsidise automobile with huge streets, highways, bridges, and tax credits on many wastefull automobiles. They make subways look pretty cheap, and thats not counting the CO2 or emmissions problem. Our national security is a farce when we are importing 70% of our energy.

So be a chump. Label yourself and others Conservative and Liberal rather than take a look at reality-anyone who does this with the peak oil situation is just stupid and gullible. Its an old totalitarian trick-divide and conquer.

I guess its time to confess to my dark secret, Rove is my ex-husband-in-law. His first ex-wife was my third ex-wife. This is a relationship recognised on the Jerry Springer show and in any trailer park in Texas. It makes me overly sensitive to neocons.

http://www.ac.wwu.edu/~stephan/Rulers/norman.html

William the Conqueror down to Edward III.

Your story is almost as good!

I remember his ex wife was a Dallas oil heiress, and that brought him to Texas?

The man is the political genius of his age, although the strategy of 'divide and rule' hasn't quite played out: they vacated the political centre and the Democrats have, for the mo' at least, occupied it.

If they hadn't invaded Iraq, then I think things might have come out very differently, so you could say Rove was in part ruined by the materials (ie GWB) that he had at hand, rather than the strategy itself.

The benefits aren't capturable (entirely) by the operator and user.

If you use public transport, I benefit because I can drive to work more quickly, there is less air polllution, etc.

It's an uncaptured positive externality problem.

Interestingly, in the UK, when new roads are proposed, they are allowed to calculate the uncapturable externality (ie benefit to society as a whole) in the cost-benefit equation.

This is not the case when new rail systems are proposed.

In a true Libertarian perspective, ie an economic efficiency one, you would want a system that captured the benefits of taking public transport, for the operators of public transport systems.

Taxes such as the London congestion charge are a first step down this road.

Transit is and has long been the great Rorschach test of peoples attitudes about....well, just about everything.

My father was from a rural area, and hated buses and the very idea of them. Buses were a sign of poverty. My mother was raised in the city and was disappointed there were no buses in the country when she married and moved to a small town. She did not learn to drive until I taught her in her late 30's. It was one of the happiest days of her life when she got her drivers liscense. :-)

Trains are more interesting. Older people have a soft spot for trains running out through the country, but are not so keen on commuters or "EL" trains, such as are seen in the city. And let's not forget the helll that was most high school kids memory of riding a school bus, a moving torture chamber of bullies and jockying for position that often rivaled "The Lord of The Flies."

I got a job and saved money to buy my first car so I could drive to school, a waste of fuel, yes, but a JOYfUL change for me.

What has long been lacking is a very civil and well managed transit system, more in the European mold, that would be more like a cafe than a cattle car. Some friends of mine and I once did some pretty involved study on the city of Louisville KY, considering a mixed light rail or bus and river ferry system, to carry commuters/shoppers from the prosperous east end of the city down the river to the downtown office and shopping area. The distance is actually very short, and the river offered free real estate requiring no building of track. With only a handful of buses and a few nice river ferries, most of the city could have been covered.

There was no real technical barrier to the whole project, but we had to admit it....as long as fuel was cheap, there would be little ridership. What boosters of mass transit refuse to admit is that most people want a car, for weekends, for "just in case" for social reasons (back to the Rorschach test, try to impress a woman on a date by going by bus or commuter train and you will get a fast lesson in reality) and once a car is purchased, the fuel even at current prices is a very small part of the total cost of ownership, and is miniscule if the car is not driven great distances.

I have always felt that trolleys and trams succeed in Europe for purely social/psychological differences, and not simply because fuel is expensive there.

Here's a free prediction, probably worth what it cost: I think privately owned electric cars will have a bigger impact on fuel consumption than mass transit ever will, not because they are demonstrably superior but because they fit the American mindset better.

Roger Conner known to you as ThatsItImout

Indeed they did not succeed. They were widely abolished after WW2 throughout Europe. Trams were loud, screeching and badly maintained. Citys didn't want that wiring in the streets any more (that's why Bordeaux/France got a tram with a third (power)rail, that is activated by the weight of the train. This system failed to work at the day of opening, with the french president on board ..).

And, of course, streetcars are obstacles to driving, perhaps the most important reason to get rid of them.

These days a new tram line in Paris/France is opened, with HiTech trains, described as "superbe" by their drivers, very silent, very effective.

France is described as the new tram wonderland.

Not everyone threw away what they had.

By the way, I think Strasburg/Strasbourg uses the same type of train - they are very quiet, very convenient, but not that well suited for heavy ridership somehow. Just an impression for a couple of years ago.

For very different reasons. If you have experienced a ride on the East-Berlin tram before 1990 (during the GDR era) you will remember one. They couldn't abolish their tram because the socialist subjects had to wait more than 10 years until being rationed a car. So buses and street cars had to do.

In second-biggest western cities such as Nuernberg or Karlsruhe the tram was kind of tolerated for decades, though often majorities of car drivers were hostile to it. The main argument against it was municipal deficits in comparison to poor ridership/comfort and so on, but the real reason is, and was, that they were hindering individual (car) traffic.

The Karlsruhe region is an exception in Germany. Most regions could learn a lot from the planners of the Karlsruhe-Bretten-Pforzheim rail system, which is exemplary in entire Germany.

Unfortunately it is true what someone said: "Car drivers love transit. The others should give up driving and change to transit. The ultima ratio is, and is to stay, "cars first".

Transit will not work as an incentive, it will definetely not get drivers out of their cars; that is wishful thinking. Restrictive measures are necessary (and will not happen since in a democracy those who implement them will be voted out of office).

Our great poet Heinrich Heine knew it - already in 1843 - when he wrote:

"Womit man einlullt, wenn es greint,

Das Volk, den großen Lümmel."

He didn't know cars, of course. But he knew the people.

Car pooling with efficient small cars is at least as environmentally friendly as rail.

To illustrate my point. My small 5 year old Italian Fiat Punto not marketed in the US- but the best selling gasoline EU car in the mini segment weighs some 1000 pounds, 80 hp , EURO NCAP 4 star, emits 140 g CO2 per km (even 44.8 mpg average on my 2000 mile summer holiday in France). With 2 passengers well below 50 gram CO2 passenger km. The FIAT car fleet is by the way the lowest consuming car producer in the EU with an average 139 gram CO2/km - see table page 2 here. http://www.transportenvironment.org/docs/Press/2006/2006_10_25_car_brands_co2_en.pdf

Rail emissions:

Now most rail data for emission is in the range of 40 - 70 gram CO2/passenger km. This http://www.transwatch.co.uk/transport-fact-sheet-5a.htm

UK study gives ( table 1 : 14.4 gram times 3.67 = 52.8 g/passenger km )

So my humble conclusion is that Car pooling could be as good as rail - or even better, at least in terms of energy use and emissions and for reducing congestion.

regards

And1I see nuke as not more than 50% of US grid under any reasonable scenario.

Best Hopes,

Alan

- In UK 43% of passenger rail emissions and whopping 96% of freight rail emissions are due to diesel powered engines. Electrical trains are more CO2 efficient - south east is showing 12.5g/pkm vs 16.9g/pkm for intercity.

- The study is comparing real-world data for trains to theoretical data for lorries and cars. For example 10mpg for a coach and 50mpg. for a diesel car are not realistic real-world estimates, IMO. There is technological overhead, stop/go urban driving reduces MPG, etc.

- The biggest part of the CO and SOx emissions are from the diesel trains.

Conclusions: instead of moving rail to road transport, better electrify your network and build more carbon-free electricity generation. Increase the passenger rail load factor. Overall the potential for CO2 reductions in rail are an order of magnitude higher than for road transport.Only if you compare to ICE road transport. Electric vehicles use less electricity per passenger mile than rail.

You're making things much more complicated than they need to be. For instance, "materials costs, production costs, reproduction costs" seem to be redundant. "road infrastructure, public education, licensing, policing and health costs. " are all the same or cheaper for EV's. Policing???

EV's cost about $.02 per mile for electricity, versus $.10 for ICE's. They're simpler, and easier to make than ICE's: simpler transmission (the Tesla has only 2 gears), safer (no more hollywood exploding cars), have lower maintenance costs, negligible pollution at the vehicle and almost zero total pollution if powered by renewables. The Tesla is so expensive because they're only making about 200/year in the first year. Still, it's cheaper than comparable ICE sports cars.

The only barrier is batteries. Batteries are now light & energy dense enough to make the Tesla possible, but they're still too expensive (at $20k for the Tesla battery pack) to compete with really cheap gasoline - an EV would be competitive with gas at around $5-6/gallon.

The Tesla battery pack will likely cost about $.20-30 per mile, depending on miles/year. ICE's cost an average of $.10 per mile for fuel, and another $.35 per mile for everything else. All told, EV's probably cost about $.55/mile now, vs ICE's at $.445 (per IRS).

Battery costs are falling relentlessly 7-10% per year and are likely to fall faster with next generation li-ion chemistries with much higher cycle lives. Gas prices will rise, and the two lines will cross in the next few years. Of course, if you were to include all of the external costs of oil, EV's would be cheaper right now.

Someone make a real utility vehicle for the whole family that can compete with a well designed diesel or hybrid and we talk. We shall also talk about the extra power plants and power lines that will be needed to recharge that sucker once there are millions around.

:-)

No additional power plants and power lines would be needed to recharge: almost all charging could be done offpeak with current infrastructure (see the recent DOE/NREL study for verification), and additional power could come from wind.

Policing. Transit systems require policing. So do personal transport systems, including attendance at collisions. The point is that they need to be compared when preparing the balance sheet.

Download pdf on Rail Transit In America: Comprehensive Evaluation of Benefits. Chose Executive Summary or Full Report. Not exactly what you asked for, but close.

Best Hopes,

Alan

What are you concerned about in particular?

I.e. he's asking for a comparison of EV's with "an electrified rail mass transit system."

His first line seemed to imply a comparison with space-travel, which would suggest that EV's might be impractical, or inferior to present day vehicles. Apart from the basic question of battery cost (which I tried to address), I can't see any reason to think that way, so I was puzzled.

I'd be delighted to see a thorough-going comparison of all costs & benefits for EV's and rail. I think that's the thing that Stuart is trying to start to build.

EVs will have (when they arrive) minimal in any indirect energy savinsg by altering the Urban form. Most Urban Rail energy savings will be via indirect energy savings.

Alan

Again, I'm just trying to remind people that "road transport" isn't just Internal Combustion Engine cars, it is also EV's, and EV's are indeed among the solutions to Peak Oil.

I agree with "silver BB's". I think rail is great, though more for the indirect, hard to quantify benefits than for the direct costs like energy.

Rely solely on rail? 1) As you note elsewhere, it likely isn't going to get the required commitment, 2) it would be much more expensive than a pluralistic approach, and 3) rail is a centralized, government, long-term capital expenditure kind of thing, and EV's are a consumer-side kind of thing, and the two are going to happen simultaneously.

I think people will get very discouraged if they think rail is the only transportation solution, and I think it's a mistake to say so.

EV's will be much cheaper than scrapping the suburbs: they might cost another $100 per month at most. That's much cheaper than moving and losing one's home equity, paying much higher housing prices in the city, etc. I'm willing to pay 3x per sq foot to live in the city, but most aren't.

Some months ago I read Amsterdam intends even to use trams for freight transport (and to more and more keep the trucks out of the downtown area). So the Amsterdam tram may also be a hopeful story.

By saying "not succesful" I was trying to describe the past 50 or 60 years in Germany. The tram was abolished in virtually all major cities, as Hamburg or Berlin.

My personal view however, is that trams are by far one of the best means for urban transportation. There are new, modern trams in Nuernberg - really cool. But they are not cool for the average car driver.

Germany had the misfortune to have its major urban centres completely destroyed, at a time when urban planning philosophy was (post war) coming to favour the car. By contrast Austrian cities were not so badly hit (out of range of Allied bombers) and Dutch et al. cities were not targetted (friendly civilians rather than enemy civilians).

(there were similar effects in a number of British cities from the Luftwaffe bombings. The cities were rebuilt, but the tram systems never recovered from the damage.)

As of Germany that's not correct - quite the contrary. Since more and more buses were needed during the war the tendency to close down tram lines was significantly slowed! (Shutting down trams had begun long before the war - just at the time when car traffic started growing - or better: sprawling).

Trams were about the first means of transportation to take up service again even in totally destroyed cities as Hamburg or Berlin, and stayed in service until end of the sixties.

At first they were lots of incidents with cars, not used to look at the "new kid in town".

But don't you have problems with pedestrians getting hit? You rarely see tracks level with the platform around here, because Americans, always in a hurry, will try to run across the tracks and beat the train. (I used to do it myself, until they raised the platform so high you couldn't climb down any more. Probably on the advice of their lawyers.)

We are in population overshoot anyway right? Lets get the stupid people off the planet 1st.

I get so mad at people that make a big deal when I plane crashes. I'm always like, "Dude..... Airplanes are the safest thing in the WORLD. Cars.... cars WILL kill you"

But plane journeys tend to be far longer per journey.

On a per journey basis, the death rates are much closer (I don't have the stats to hand). Planes don't crash that often, but when they do, the effect is gigantic.

Interesting that the number of deaths per aviation incident is steadily rising-- planes are bigger, and when they do crash more people are killed. This is true even if we strip out 9-11 (the largest aviation incident in history).

Your conclusion 'Under the assumption that the post peak-oil period involves still further rises in energy prices, if we invest even more heavily in transit, it would appear to me that we are likely to get even more diminishing returns.' seems well founded at one level, which is the practical/political level typical in America - in fact, it is likely that a declining revenue base will lead to such well-founded arguments being used in discussions concerning how to keep things running along.

The scary thing is that I think Kunstler's point about having reality being the source of America's next discussion about how to live is actually valid.

This is not a discussion of the best forms of transit - I think the 'heavy' and 'light' rail distinction pretty artificial, and that European style systems, which essentially fit into normal traffic as is, are the right thing to consider.

But your work is again disturbing in showing just how deeply the changes must run.

I may add that at least where I live in Germany, the local transit system (KVV) is definitely pulling riders from cars, but the system makes a real effort to provide a service which can compete with a car on a price/time level. Only a few cities in America come close - SF, NYC, Boston to an extent, and in my memory from the mid-80s, Denver - which due to pollution problems, had a fantastic 24 hour bus system, which in no way could have been even 20% covered by fares.

I've lived in SF, and silicon valley, and can categorically state that the public transport is an abortion. Just the fact that CalTrain is n blocks south of the centre of the city is a testament to the bad planing.

The commute from SF <-> Palo Alto would try anyone's patience. An equivalent commute in europe / japan...

BART is an textbook example of poor transit planning. It uses a 5 ft 6 in rail guage instead of the standard 4 ft 8.5 in, precluding the use of existing right-of-way, motive power, or rolling stock. The initial computer system designed to run the trains failed miserably. The system, which started carrying passengers in 1972, failed to connect to SF International Airport (a mere 14 miles from SF) until 2003! That 14 mile extension cost $1.55 billion to construct. To this day you need to take a shuttle bus to connect from BART to Oakland Airport, and forget about connections to San Jose International Airport.

Auckland is even worse than San Jose. There are all the geographic issues of a Seattle or SF - hills, narrow streets, bridges, no bike lanes. Plus public transit is limited and riding a bicycle is extremely dangerous. I avoid Auckland like the plague it is.

:-(

The secret is to lose weight, your ankles will lose that "about to break" feeling if you drop 100lbs.

And fundamentally over capacity, at least in the core 7.45-9.15 and 6.00-7.00 commuting hours. Some of the Tube lines are running at more than 100% of theoretical capacity.

My wife takes the kids to school etc. In almost all cases, even on SF's much better than average public transportation, driving takes half the time of walking/Muni. Therefore she almost always drives.

"Under the assumption that the post peak-oil period involves still further rises in energy prices, if we invest even more heavily in transit, it would appear to me that we are likely to get even more diminishing returns."

The investment being made in light rail and other modes of expanded transit represent some respectable long-term planning, and can be quickly thumped by showing their short-term costs. There are a number of factors that affect how people become regular passengers, including long-standing driving and lifestyle habits, housing choices and urban designs that may barely look at 'distance to stations/stops'. (while in NY, this is in many/most real estate ads as a clear advantage) Add to that, of course, the reluctance of much of our society to acknowledge our energy precariousness, and it's clear that the investment may not see it's returns quickly, but is as smart an investment as we could be making to prepare for such a likely contingency as a major energy disruption.

So while your conclusion may be partially correct, in that the investment will still be a heavy burden to bear (and keep increasing) while so many Luxury Hummers are still boppin' along out there, don't you think this is a vital and useful piece of infrastructure to be expanding upon? Just because they haven't yet given up on the F350's and the mondo-commute is hardly going to convince me that they can't, and that we shouldn't be setting things up for that eventuality just in case. It may not be possible to make a concrete economic case for it, unless you look Below the bottom line.

Bob Fiske

I think the 'Big Dig' qualifies as a sad example of many wasted tax dollars (subsidising a lot of Drivers), the Medicare non-bargaining policy, the Tax Breaks to XOM last fall, when they were hurting so bad.. the EROEI on the war seems bad, unless you're in Al Quaeda.. - but looking at poor short-term ridership gains as a gauge on transit development seems to be a funny target for cleaning up our budget problems, particularly the ones we can expect to face when people really can't fill their tanks any more.

Best Hopes for spending 1 month of Iraqi spending on new Urban Rail each year,

Alan

How likely is any of that?

I don't mind putting some money into transit. I mind claiming that it is the solution to the PO problem.

Cost-benefit analysis assumes that transit systems and cars serve the same goal. In most instances they don't. Transit systems are mostly a matter of quality of life of a city or a region. Having a car is mostly a matter of quality of life of an individual.

It is therefor a judgement call how much quality of life a city wants to offer to its citizens by building a functional and useful transit system.

PO does not threaten transit systems because cost of energy is not a serious concern. But PO threatens private car ownwership for those who bought the wrong car.

My comments are all fundamentally based on these and similar thoughts which seperate concerns. Public transit takes over the role of cars in very, very few places in the US. New York and Washington, maybe San Francisco and a few others. Everywhere else being on transit sucks. Take it from someone who does not own a car. I couldn't possibly move to L.A. and live the same way I do now. It just does not work.

So who (on The Oil Drum anyhow) is claiming transit is the solution? That's a strawman as far as I can tell. Transit is one silver BB among several others. And it's a necessary BB.

Transit doesn't have to be gold-plated, either. There are European cities with very inexpensive rapid bus systems. Just separate a lane with a continuous wheelstop. Space stops 1/4 mile apart instead of every block. Sell boarding tickets or cards in stores or kiosks, anywhere but from the driver. Voila! You've got yourself a cheap transit line that can get across town as quickly as a car -- or quicker, if traffic is heavy.

About cost-benefit analyses for transit, please see Determining the Value of Public Transit Service.

I took an 1898 subway to and from the ASPO convention in Boston. I take the 1834 streetcar line (on 1923/24 rolling stock) pre-K.

Best Hopes for Long Term solutions,

Alan

http://bayrailalliance.org/caltrain/dtx/

http://sfcityscape.com/transit/transbay.html

Miami is building a Miami Intermodal Center, connected to the airport via people mover, all of the airport auto rental would be located there. Served by Miami Metro "Subway in the Sky", Amtrak, Tri-Rail (local commuter rail), Greyhound, and local city buses.

Alan

Huh? I have no idea what you just said. Venezuela will provide you a writing coach. Free of charge. I'm serious. I'll give you my best one. You need help, my friend.

In these paragraphs, Stuart concisely summarizes interpretations of all the graphs he presents. That isn't as easy as it sounds.

Stuart says... (blockquotes)

While oil got more expensive, we spent more on transit infrastructure...

So, with that money, we built more available transit seats for people to use. However, the percentage of seats getting used by people went down. (it is also noted later that the total number of seats being used went up, while the percentage of seats being used went down)

The cost to run the transit networks went up, and quite a lot too. The proportional amount the cost to run transit went up was greater than the increase in passenger numbers. That's not good, because it means that the cost per passenger went up. Taxpayers are paying a much greater subsidy per passenger on transit compared to 10 yrs ago, even though ridership is up.

Since we spent large amounts of money improving transit infrastructure, but the end result has been an even greater cost per passenger, this suggests that investment in transit is probably a really bad idea, and offers diminishing returns. Looking back, we can see that the most recent spending has resulted in higher overall costs per passenger, therefore we can surmise that the spending that took place prior to 1995 resulted in better costs per passenger than the spending that took place after 1995. The best opportunities to spend money on transit had probably already been used prior to 1995. Spending after 1995 was on projects that on balance weren't really that great.

Over the period of study, between 1995 and 2004, the cost per passenger for the government to run transit increased on average for all categories, but it increased most for light rail.

If we keep doing this stuff, the end result is more likely than not more of the same.

That means, increased numbers of people using transit, and an increased cost to the taxpayer per person using transit. Put those together and you get a big hole in government spending at a time when presumably, money for projects will be hard to come by.

Hope that helps! Free of charge ;-)

On behalf of all those who, like me, mainly lurk, thank you Stuart for your writing. It is highly valued. When you disappeared some months ago, I very much regretted not having thanked you for your posts.

You don't seperate rolling stock from geological capacity.

Adding rolling stock does not automatically propel people to use them - it has a relatively minor effect once you get past a certain number of trains an hour. It's pushed upwards by high ridership, it doesn't push ridership upwards.

Adding track and stations, on the other hand, directly adds to ridership in a more than linear fashion - the reach of the network expands, and so more people use it rather than driving, and so it can support more tracks... TOD takes over near the stations, because the walking distance of a building near a station has expanded from 2 blocks of the building to 2 blocks of any station.

In Ottawa, Ontario where I live, we have a well developed public transit system, including light rail. One lane of the main cross town commuter highway has been reserved for public transit. The bus malls are bright, clean and generally safe, as is the entire system. I have no problem letting my teenagers use the system unaccompanied.

The bridges between Ontario and Quebec connect the greater national capital region and are heavily congested with commuter traffic. However, one lane has been reserved for HOV-3, public transit, and taxis.

In spite of all this, public transit is under utilized. Commuters find themselves parked on the highways and bridges while the public transit lanes remain empty, except the the occassional passing bus.

Maintaining the bridges at HOV-3 instead of HOV-2 is a bit of social engineering which doesn't appear to be working. As well, HOV-3 is not well inforced and there is a lot of defecting.

Allowing taxis to use the transit lane, to me, sends entirely the wrong message. If you cannot afford a car, are environmentally concious, or can simply fit public transport into your lifestyle you can move along swiftly. On the other hand, if you can afford a private rent-a-chauffeur, you can also take advantage of the public transit system.

On another front, there is a general bias against urban sprawl in Canadian cities even though our largest cities suffer from it greatly. In Ottawa, just outside the core within a 15 minute walk, are beautiful, old residential neighborhoods with expensive, well maintained homes.

However, until recently, the true core of Ottawa has had some poorer, affordable housing that attracted students, welfare recipients, and the homeless who rely on the many shelters.

This is all changing with the aging boomers. Downtown Ottawa has become "the place to live." Expensive condominium appartments are springing up everywhere in the heart of the city and in the run up to the recent municipal election, the incumbent alderman for Ottawa Center ran on a platform of moving out the homeless and shelters. He never quite got around to saying precisely where they were supposed to go. Perhaps out to the suburbs.

If relying on the charity of wealthy downtown boomers is the "job" of the future, at least these poor souls will have access to an excellent public transportaion system to take them to "work." That may increase ridership considerably.

I've actually noticed this in New Westminster, where I live. I'd bet the majority of the people here are over 50 or in their 20s. In that sense, at least, there may be some hope for rejuvenating cities, since both the oldest and youngest (autonomous) generations are starting to return to cities for the accessibility, price (?), and perhaps potential for socializing.

That means people who drive less are subsidizing those who drive a lot; those who drive mainly on city streets are subsidizing those who mostly use highways.

See Fueling Transportation Finance: A Primer on the Gas Tax

Does anyone know some references about this?

Traffic: Why It's Getting Worse, What Government Can Do

Why Traffic Congestion Is Here To Stay, And Will Get Worse

Another Brookings Institution study:

The Effect of Government Highway Spending on Road Users' Congestion Costs

Generated Traffic and Induced Travel by Todd Littman:

However, if we simply look at the short term return on our transit investments and then compare that to the next phase of fruitless highway expansion and neighborhood destruction, then we make poor investments in the long term. Cities that excel as far as non auto transportation started planning and building decades ago. They are now reaping the benefit. Would any of these cities like to go back and reverse their investment profile or road vs transit?

The Long Island Expressway, AKA "The World's Longest Parking Lot," was the subject of a planning study awhile back. It came to the conclusion that even if they double-decked the entire highway and doubled capacity, it would only encourage people who currently take the bus or LIRR to drive, and the congestion would be just as bad as ever.

The DOT decided it wasn't worth it, and were upfront about it to the people affected. They understood. Why spend billions to get the same problem you already have, only uglier?

If any American city is to try electronic congestion charging, I suspect it will be NYC first. Or, oddly enough, Los Angeles, which despite stereotypes has a relatively high population density (1) and a history of innovation.

I was struck by the number of SUVs in NYC though. In Texas, sure, but I would have expected NYC to have the same numbers of SUVs as London (about 1/8).

(1) some distortions there, in that that number is based on the Census Metropolitan Area-- I've heard it said that if you adjust for that, LA doesn't look that dense. Nonetheless, LA is apparently of above average density amongst American cities.

But do they ever vote out County Commissioners? Not in my life time, and I'm 55.

There is not a major city on the planet without traffic jams at rush hour. Due to the diminishing returns of paving a city (it pushes uses farther apart, requiring even longer-distance travel across the paved expanses and disadvantages other modes) as the above posts noted, it is impossible to build enough auto capacity to avoid rush-hour traffic jams.

So traffic-jams are not only "politically sustainable" but an inescapable fact of life.

Name one major city that lives without them. A city without gridlock does not exist.

Transit does not serve to prevent gridlock, but only provides an alternative for people who prefer reading a paper on a train to staring at a bumper.

The City of Boulder, which would be the recipient of said traffic, is resisting this approach. They would prefer no additional lanes with the extra traffic taken care of by light rail and bus. This political entity is, in essence, saying that they refuse to bow to the paradigm that says we should always acomodate projections of additional traffic with road widening. They are a political entity and will, I belive, be supported by a good majority of the citizens of Boulder.

This approach is not political suicide everywhere. No doubt there are jurisdictions where this approach would be suicidal. Not here.

D.C. was often gridlocked when I lived there twenty years ago. My guess is that their mass transit system is successful, in part, because driving is often such a distasteful way to get around, considering the alternatives.

Hope Springs :-)

Alan

Transitioning to significant bicycle usage would also help make the big drop in fuel usage that I think we need.

Here in the Atlanta area, I have a difficult time imagining public transit making very big inroads. Everything is spread out, so there is no concentration of traffic going to a single location. I don't see rebuilding infrastructure in concentrated locations at this late date to be a feasible option.

I find the section of gas taxes very interesting since it shows that the gas tax in Georgia pays almost none of the cost of roads so most of the money comes from other sources such as sales and property taxes. It's especially enlightening since the bulk of the population of Georgia believes that gas taxes are too high and that they more than over the cost of roads. As long as the general public remains willfully ignorant of the actual costs of different transportation modes, things are not going to change.

The report also shows that the roads in Georgia are in extremely good condition (Charts 14, 15, 16, and 17). This tends to encourage more road use.

At least for the year shown in the report (2004), GA spending on maintenance and construction was very low (Exhibit 8). This seems to correlate with the low GA gas tax, so less amount available in total to spend. But how can the roads be kept in such good shape, with limited spending? Was 2004 an unusually low spending year?

The nice part of transit is that you don't have to drive; the bad part is the loss of (percieved) control. Instead of sitting at red lights, you're sitting at the station - waiting for your connection.

Worse yet, if the train I can't board is the last one home at night, then what am I supposed to do? (Just ride the bike home? If that had been practical, what in the world did I need the train for in the first place?)

But basically, it's the downward spiral-- happens to any public service.

You can see assaults like that taking place against public education, mail service, etc. If you reduce the quality and usership by enough, you get a 'tipping point' and wholesale abandonment and collapse of political support.

The problem of mass transit in the US is a classical chicken & egg problem. Nobody rides it because its not reliable and nobody invests in it, because nobody rides in it. Therefore unless a major effort is undertaken to invest the huge upfront resources that it requires, I don't see people accepting it, ever. The mistake was made with the urban planning that started some 50 years ago and now I'm afraid is too late to fix it.

I was late to my job interview, because I had never ridden a subway before and got on in the wrong direction. I was half an hour late, and figured I'd lost the job. But the guy who interviewed me didn't even notice I was late, and hired me on the spot. I later realized that half an hour late is on-time to the average New Yorker. It's places like Minnesota, where (relatively) empty highways beckon that 10 minutes late is late.

Much has been written about the passive-aggressiveness of the Midwestern personality, and it's worth researching.

Then reflect on the fact the the basic Amerian personality is Midwestern.

Yeah..real people pouring their hearts out.

I have sat in a few bars in NY. You make a simple conversational comment and the guy next to you opens you up like with a canopener. They have compassion a mile wide and a micron deep.

Whatever happened to the old Yankee inguenity? The old "use it up, wear it out, make it last" mentality? I spent a year in upstate, and saw a few old Yankees. Some good folks in Woodstock and Bearsville.

Going to White Plains to our hdqtrs I meet the filth and scum of the universe. Then to Manhattan and sheer terror. I saw a couple standing beside their VW van as it burned to the ground. NO ONE helped them. I saw how the cabbies drove and how if you didnt have the guts to face the crazy traffic down you just sit there forever.

Yeah it was really great. You can have the armpit of the world. I will stay in Kentucky where neighbors help you instead turning their heads and walking away.

Keep repeating your mantra, "I love New Yawk. I love New Yawk." You know you hate it.

This is after having visited in the mid 80s, and vowed never to visit again: a scary place 'Escape from New York' was almost a reality. Of course in the 90s crime and the streets were cleaned up, but there has also been a change of mood.

But after 9-11, everyone says, it has changed-- people wear their hearts more on their sleeves. I certainly found it so.

Bicycles are, in fact, the only way that we can meaningfully increase traffic thru-put.

Buses have been expanded, to the point they contribute to congestion. The Tube (subway) is over capacity, and a new £16bn extension is delayed till post the Olympics at least (and maybe never) despite the City (home of 10% of UK GDP) saying that it is vital.

The Congestion Charge has reduced traffic by c. 15%, but by less at peak hours.

One of the key things about public transport is that it has to be pretty good before people start using it to its full capacity. That means that you have to go through an expensive capacity-building phase before you really see any significant take-up. From the capex graph it looks like the ramp-up started around 2000 - perhaps the utilisation will begin to rise? Major cultural shifts don't necessarily happen on the same timescale as the construction projects which enable them.

Another question is how and where that capital expenditure is being spent. Does the US manufacture its own rail infrastructure, or is it imported? Because if it's imported, then the decline of the dollar since 2000 might play a significant role.

Of course, it's also possible that the money was spent on badly-designed boondoogle projects... Or that Americans really are irredeemably wedded to their cars to a much greater extent than we Europeans.

Bikes are the only form of last-mile transportation that is effective. But they are also completely incompatible with current bus and train designs. That is not only a shame but should also be a call to designers to change railway cars and busses to accomodate more bikes.

But it is pretty obvious that current bike designs are not very space-efficient. We need a standard mechanism to fold pedals and handle-bars and make commuter bikes stiff, flat object that can fit into a standardized bike compartment. The current method of hanging them on the bus or somehow jamming them into a heap inside a train car is ridiculous. On Caltrain the conductors are advising people to get folding bikes because those can be taken on any car, not just the bike car. Now... a folding bike is not exactly a very good bike for any purpose. So the choice is between a poor riding experience and not getting on the train...

Bikes are clearly better vehicles on nice, clear, dry roads. On crowded sidewalks, at relatively low near-pedestrian speeds the segway will do better.

I agree that the Segway has been a godsend for a lot of disabled folks.

You might want to resume your medication....

I also think that the "If you build it, they will replan" idea will have more sway in times of tighter LTF supplies. Businesses and Apartments in the 5-boroughs of NYC have been, for decades now shifting and blossoming in relation to their proximity to transit. Nothing stands still (unless the subsidy of a cheap energy supply allows it to hover like a Helicopter.. but that get's pricey) This is an opportunity for the Forward-thinking real gamblers to figure out where the precious transit access lines/points are now sitting undervalued, but could become new focal points of activity and regular foot-traffic.

In America, at least, we will never make much progress by simpling tacking on mass transit while still making every effort to accomodating the demands of increased auto traffic. One needs an affordable faster alternative to auto traffic to have a significant impact on people's transportation choices.

I, for example, chose to take a bus to work when I worked in Denver. The first part of my journey was clearly superior to the automobile as the bus was able to take the HOV lane. In the middle of Denver, however, the bus was forced to share the interstate with all the other autos. I chose to put up with this unsatisfactory situation anyway because I was so committed to public transportation. I can understand, however, why the vast majority chose the auto as it was a much faster way to get to work.

When I lived in Germany, however, taking transit was a no brainer. The bus that took me to the subway was a less than five minute walk. The subway came by every 3 minutes during rush hour and deposited me a station which was right by my place of employment.

Elsewhere, Alan has reported the massive increases in transit ridership in the D.C. area. I can understand that since that area, where I used to live, has been an auto nightmare for decades. Rather than try to fix the unfixable, the freeway system, D.C. chose to focus on their mass transportation system, including their fine subway system.

One question would be, how does D.C. stack up against this this overall analysis prepared by Stuart.

Despite these numbers, I think we need to continue to press on with expansion of our transit system. At the same time, however, we should do nothing to make it easier or even bearable for people to drive their cars in the city. Things will change, but it will take more than higher gas prices.

God forbid the facts should interfere with our theories...

I suggest a very crude rule of thumb.

If you have a large, very densely populated city (on the US scale) that doesn't already have a transit system, or has an incomplete one, it may make sense to add transit to it. Otherwise, it's a boondoggle.

What has driven me crazy about all discussions about peak energy is that few take the time to consider the longer term consequences of trying to maintain the status quo. Where's the Precautionary Principle?

I know of many people around here who make several trips a day between home and town for errands and shuttling the kids to activities. Building public transport to support that would be nutty.

I believe George Monbiot's book "Heat" has some detailed discussion of transport options in the UK.

We need to break this down to see where additional capital expenditures would make sense. I would agree that your analysis demonstrates that simply building hoping they will come will not work.

Transit alone is not the solution, of course, and should not bear the full burden for 'See, it didn't work'. An effective long-term plan has to incorporate the ways transit can be a precursor to a shift in community planning.

Just cause they didn't buy enough Betamax, didn't mean it wasn't a better format. In that case, it did prove that it wasn't better enough for the market to demand it over VHS. Question is, will mass-transit provide solutions to energy challenges enough to be worth the heavy setup prices?

SS seems to suggest that it doesn't, but that's based on New Investments and New Ridership, during a brief, strange period in the US that included $11/oil and two oil wars (at least), a massive Tech Boom for computing, and a rebirth of 'America First'ism .. does the rest of the history of Mass Transit offer any overall benefits that may help reframe this issue?

Of the $10 billion/year, roughly $2 billion in recent years has been for New Starts Urban Rail.

The current administration has heavily pushed BRT (improved bus) and pushed against Urban rail. I agree with Stuart that more BRT does little good.

IN ALL CASES rail is cheaper to oeprate than buses (even though buses get "free streets").

The operating economics of early light rail (San Diego & Portland as good examples) were better than buses but are far short of the economics today FOR THOSE SAME LINES.

New lines have been added in both cities and the first lines have "matured", altough they are still maturing as new TOD goes in each year.

The economics of maturing systems are interesting. People get better at what they do the longer they do it (to a limit). Efficiencies of scale lower costs as new lines are added. Rail ridership rises year by year on the majority of Urban Rail lines. As ridership rises, unit costs drop.

Comparing Portland of 1986 to Portland of 2006 would make one think that '86 Portland was a waste of money ! Why didn't you build the much better Portland of 2006 ?

Why. building more '86 Portlands will take you on a downwards spiral of ever increasing costs ! 2006 Portlands are "OK" but small & trivial on the national level (Portland OR has meet Kyoto CO2 reductions BTW). However, diluting them with more '86 Portlands is the path to disaster !

And we spent many billions on buses and more people did not ride more buses, so one must conclude that we should not build Urban rail (implied Urban Rail = Buses, they are all "transit").

Best Hopes for City-by-City case studies, more can be learned that way.

This is a key point that transportation engineers have analyzed in detail. The denser the development, the more viable the mass transit system. So what is the the minimum density that should be considered? Studies indicate that around 4,200 persons per square mile is an effective minimum. That translates to 6-7 persons per acre, and at 2.5 persons per dwelling, that is 2-3 dwellings per acre.

That's enough for stand-alone garages and swimming pools. At least 25% of the U.S. population (and most likely more than that) lives at these densities or higher.

I did a rather nasty commute once: five hours total for a distance that would have been less than an hour and a half by car. Of course the problem was that the train pulled into the station the minute the bus left and that the next bus was 29 minutes away. In other words: I had to waste a full hour on waiting and it took the bus longer to get me down the last 7 miles than it had taken the train to get me down the first 30. Had the company been one mile down the road, there would have been no bus at all.

One thing that's muddying up these Oil Drum threads on transit is that the discussions cover both current customer preferences and potential post-Peak scenarios. I am interested in the potential for transit post-Peak: What types of transit and other transport solutions can be quickly and cheaply implemented to cope with critical fuel shortages? Whether and how travel behavior will change? Whether and how land use and density will change, and at what rate?

Technically and economically, there is nothing prohibiting rapid change for some of these factors. For instance, density can increase simply by subdividing homes or building accessory units. The more persistent obstacles are cultural and political.

GPS is of no use if the busses are running on half an hour schedule and have rarely more than five passengers. Running them more often doesn't help because the train still doesn't go where people need to go and not everyone is like me and is accepting of a 3.5 hour instead of a 5 hour commute if one pulled all the stops in that system.

This is not about intelligence but about the simple facts of life: you can't cover random traffic flows with public transportation. If the urban area was not planned well, like suburbia, which is not planned at all but just spray painted on a random cheap location next to the highway, no amount of intelligent traffic planning can save the day. A bus works fine over three to five miles distance. Over fifteen it takes longer than anyone can stand... including me.

Transit post peak will have as much potential as before: none. One can't undo a hundred years of missed urban planning and start over. The US is what it is - vast and randomly populated.

"For instance, density can increase simply by subdividing homes or building accessory units."

Good luck subdividing a single family home in suburbia.

Look... some things just don't work. You look at them, shake your head and move on. This is one of those things. Can it be made better? Sure... Can it be made good enough? No, not really. And better is unfortunately not good enough.

For someone with the handle InfinitePossibilities, you sure have a limited view of what's possible, or how attitudes can change.

During WW II, the survivied a 6 year complete oil embargo. At the end, the average Swiss used less oil in a year than the average American uses in a day ! But their society and economy still functioned, and they had a decent quality of life.

It took almost two decades of preparation,

Please note my post elsewhere on this thread on their 1998 rail plans for 2020.

How un-American !

Best Hopes for Long Range Planning !

Alan

There are many problems with your analysis, but the absence of critical information about fixed route transit is the most glaring. I will mention one: transportation planners today refer to something called 'uplifting' when calculating the costs of installing new fixed route public transit, of which rail is the best example (bus transitways are another). Uplifting refers to the increased value of land in the vicinity of transit stations. Why is the land more valuable? Because ready access to transit increases demand for living/commercial use of the location and allows for intensification. Municipal taxes rise with the intensified development such as medium-highrise buildings. This is not theory, but a description of what happens in almost all circumstances.

Intensification takes time, but only incredibly stupid political decisions stand in the way of this market process.

The result is that overtime a 'natural' transit clientele is developed.

The numbers you use indicate an expansion of rail transit capacity, leading to a lower rate of capacity utilisation.

Like too much economic analysis, yours ignores change over time.

Your analysis does not permit you to conclude that building a transit system in places other than very densely populated cities without an existing transit system is a boondoggle.

Depends upon you definition of "densely populated" of course.

Using 80+ year old equipment, it covered (pre-K) 80% of it's operating expenses from fares & ads.

A majority of people used it (still shut down) at least occasionally. Couple nearby walk to work on nice days to 51 story One Shell Square (about a mile away) and take the streetcar on "bad days".

Houses are a mix of 1,2 & 3 stories, plenty of "green" space.

Alan

For the 1000ths time: it is not about recovering operating expenses! For heavens sake... the problem is that rails are one dimensional and commuting is a two dimensional problem...

See Miami Plans.

http://www.miamidade.gov/trafficrelief/RailMap.htm

Dark brown lines are post-2016 plans. I would like to see 100% build-out by 2013/14.

Without additional TOD, 90% will live within 3 miles of a rail station, 50% within 2 miles. My own SWAG is that 20% will live within 3-4 blocks of a station and 40% of jobs will be that close by 2020/25.

Each station has bus lines servicing local destination.

Best Hopes,

Alan

The only thing wrong about the system is the use of buses instead of rail, especially given the higher labour and energy costs of buses. The system was designed to permit a change to rail at some future date.

There are other problems with Stuart's take on transit, not the least of which is the muddled thinking on subsidies. It is important when considering the comparative costs of transportation (or any) systems to think in terms of costs (and of course benefits) to the economy, regional and otherwise. The subsidy to a system operator to meet operating costs that exceed farebox revenue in most cases provide a benefit to the economy. For this same reason, highways are largely socialized in most countries.

A proper comparison of different transport modes has as is oft noted to consider externalities such as pollution costs. But there are other considerations: what, for example, are the opportunity costs of the dollars exported (from the local/regional economy) to purchase the energy in excess of the energy required for an alternative system? What is the impact in an energy constrained world (supply-led) of effectively unnecessary demand, because transport alternatives exist, on the operations of those providers of goods and services for whom consumption is not elastic. Ambulance and fire services are charged examples.

The essential problems with Stuart's analysis are, in my opinion, twofold: first, it is static and, second, it assumes a demand-led economy, when we are entering an era wherein the transcendant factor in the economy, energy, or even, energy-matter, is irrevocably limited.

http://www.octa.on.ca/forum/viewmessages.cfm?forum=20&topic=1194

Pittsburgh, the US city most devoted to BRT has no plans for more BRT and is currently building light rail to the North Shore, where several potential lines can feed into it.

Best Hopes for Urban Rail,

Alan

Nonetheless, it is not correct to say that BRT doesn't work in Ottawa. It moves a lot of people every day. Which is not to say that any city contemplating fixed route transit today is not better off to choose rail.

Is anyone proposing adding transit anywhere other than the dense regions of cities?

I have not heard of any plans for light rail in Baggs, Wyoming.

Essentially all major US cities have corridors with sufficient density to support rail transit, yet many of these corridors currently lack transit. Most US cities are adding rail capacity as we speak, even sprawling cities like Phoenix and Dallas-Fort Worth, but they are adding rail along the densest and most heavily travelled corridors. The densifying effect of the Transit-Oriented-Development which follows rail construction is well-documented and visible around every new rail system which I have seen. Over the centuries of useful life offered by rail systems, transit nodes will re-develop to higher densities.

For example the Cinderella City redevelopment along Denver's light rail.

http://www.realestatejournal.com/buysell/markettrends/20061207-herrick.html

-"A decade ago, the fortunes of this lower-middle-class Denver suburb were inextricably linked to Cinderella City, a mall virtually devoid of retailers, and to the automobile.

Today, where the 1960s mall and its parking lots once sat, Englewood has latched onto a new hope: 55 acres of apartments, stores and offices anchored by a stop on a light-rail line that links Englewood to downtown Denver. The $155 million development features 438 apartments, 350,000 square feet of retail space, including a Wal-Mart, and the town's library and city hall. "Our community has a new core," says Gary Sears, Englewood city manager.

Opened in 2000, CityCenter Englewood is one of a growing number of developments offering a mix of uses that have emerged around mass-transit rail lines, a trend that is particularly notable in the car-friendly West. In Dallas, Mockingbird Station on the city's light-rail system boasts an artsy Angelika Film Center, loft apartments that utilize a 1940s warehouse, and retail and office space. And the Del Mar stop in Pasadena, Calif., along Los Angeles's light rail includes 347 apartments stacked over ground floors intended for shops that will give the project a dense, urban feel amid its low-rise Southern California surroundings when it is completed early next year.

Such projects still have plenty of challenges, one of the reasons the Federal Transit Administration counts only about 100 of them nationwide. Because zoning often favors a single use, such as residential or commercial, developers must work with city officials to change the rules. Land can be difficult to assemble. And upfront costs for developers -- especially with demand to include features such as plazas and parks -- are high with financial returns often slow in coming."_

So in the case of mass transit we currently have supply well above consumption - good.

The price spikesfor gasoline the past few years have not been enough to end the Mass Delusion of the Culture of the Automobile.

It's good to know we at least we have a cushion for when the Post Peak Reality pops that bubble.

In reality... in my area a real gas shortage would leave a hundred thousand people stranded and the transit systems have the capacity to move a couple thousand more than they actually do. In other words: even if the trains went where people needed to go, only very few would be able to get on the train.

This is a typical case of "Just because you want really badly it does not make it so.".

http://www.lightrailnow.org/features/f_lrt_2006-05a.htm

Even in DC & NYC, all but the Lexington Ave line can accept more rolling stock in an emergency.

In addition plans could be made for expanding Park & Ride lots (DART lots were FULL after Katrina) in a variety of ways, as well as more buses to rail stations). Blocking off 2 lanes of nearby 4 lane streets and turning them into parking, parking on grass, commandering nearby office & retail parking, etc.

But this takes advance planning.

The slide down the Peak Oil slope will NOT be smooth !

Best Hopes for Rational Planning,

Alan

"10% is not an order of magnitude"

do you not understand?

You are a factor of 20 away from covering every commuter and all the systems that actually work are maxed out.

You want to block off two lanes of the nearby highway for parking? Be my guest... the average distance between rail system and highway around here is a mile and a half. I am sure a lot of people will love the opportunity for that walk every morning and every evening. And don't forget to charge them $7 for parking. They will like that even better.

:-)

Guys... this is getting ridiculous... you know. PO means you have to give up your freaking SUV and get a smaller car... it does not mean to dig up half of America to install yet another non-functional transit system.

What is there so hard to understand? Life is not "Sim City". You can't just erase the whole game and start over. You have to work with what you got. And what you got are highways.

I'd like to think there was a more durable system that we could start resurfacing our roads with.. but in those quantities, what would you propose? My "Sim-Highway" dream project would be Nano-machines in weather balloons, pulling carbon molecules from the atmosphere and tossing little bundles of 'BuckyBalls' and 'Nano Carbon Tubes' down for new construction.. but I bet it would be hard..

Rails used in DC Metro have the better part of a century left. OTOH, NYC subways have some worn rail that could be replaced next year. Boston rail is bas in some spots, good in others (spot replacement ?).

Urban Rail can be realistically expected to last the better part of a century to over a century with minimal work (not so true of old wooden ties).

The new Swiss rail (pax + freight) is being designed to last 100 years with minimal maintenance under extremely heavy use.

Best Hopes for Long Lived Investments,

Alan

BTW, The under construction Greenbush commuter line south of Boston should be extraordinarily long lived. Well built, properly banked, cracked granite ballast (the best), concrete ties (except at road crossings) fairly heavy rail (135# from memory), well built and about 30 light commuter rail trains/day (single track mainly, so same rail used coming & going).

High speed switches will wear in decades (3, 4 ?) and wood ties at road crossings was a mistake (IMVHO) but rest should last a LONG time. Salt is not used on rail lines, so that problem is avoided.

Yep! If we plan not to have a permanent gas shortage, as in post peak, and then we decide not to build the infrastructure to take care of that shortage, then these people will be stranded. In the short to medium term, the required investment might seem to be a very bad allocation of resources. But what of the long term?

The people in the Denver area decided to tax themselves to provide billions to expand their light rail system. They will not get their "return" for a couple of decades, if that. Many of them will be long dead before this thing reaches its full flower. Perhaps it is all just a gross waste of capital. Perhaps. Part of that decision, however, entailed a vision, where people decided that total dependence upon the auto, which has already destroyed much of this area, was simply unacceptable.

One drawback, though, is that they should have embarked on this twenty years ago. All this investment may be too late for post peak. If I were in my 20s or 30 or early 40s, however, I know where I would be purchasing real estate.

Coulda, woulda, shoulda. Great game. And so helpful....

:-)

It is also a case of one of many "infinite possibilities" not having a high probability.

S.F. has among nation's highest public transit use among commuters

San Francisco is among the cities with the highest use of public transit, according to a U.S. Census Bureau report released Tuesday. San Francisco tied with Boston, where about 31 percent of workers commute on public transportation.

The only U.S. cities with higher public transit use were New York, with 55 percent, and Washington, D.C., with 37 percent. One-third of the nation's 6.4 million people who travel to work on public transportation use systems in New York, according to the report.

Of the approximately 6.4 million people nationwide who usually travel to work using public transportation, nearly one-third live in New York City, according to a new analysis of American Community Survey data released today by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Chicago and Philadelphia each have 27 percent public transit usage among commuters. Newark, N.J. had 26 percent and Baltimore had 25 percent.

Only one Los Angeles worker in eight uses public transportation, and in Houston, only 6 percent of workers use public transportation.

Overall, 5 percent of the nation's 128.6 million workers use public transportation to get to work.

Other survey highlights:

* Nationwide, 77 percent of workers drove alone to work, 10 percent carpooled and 2 percent walked.

* Bus transportation accounted for 55 percent of public transportation use nationally; subway

Can I translate that into bad news for you:

95% of the nation's workers use their cars. Of the 5% which use public transportation, approx. 50% live in areas where the transportation systems are operating close to their peak capacity during commute hours, New York and Washington.

In other words... we could probably transport 8-10% of all commuters on public transportation systems, everyone else, i.e. 90% or more still need to travel by car.

In other words: the energy savings in the best case scenario are marginal.

...what shall we do after the first year and a quarter?

Kunstler's reality will offer shoe-leather or bicycles. I suggest to everyone to have a bicycle ready to go.Never forget that mass-produced, standardized bicycle tires wear much longer than customized, size-specific footwear. Compare the price and maximum mileage wear of a couple of bicycles tires to decent quality walking shoes or boots that won't give you blisters.

PostPeak: shuffling your feet and/or dragging your heels will be seen as a very expensive waste of shoe leather.

Bob Shaw in Phx,Az Are Humans Smarter than Yeast?

Now it is not necessary. The lower-middle class, which is where I would have placed us at the time, could afford one car. Now they have multiple cars. It's an expectation. Each kids gets a car.

Going back to the buses, giving up the second car, and reserving the only car for absolute necessities, will be unconformtable for most if not all. Who wants to go backwards?

But the basic idea driving this transporation analysis is that energy will become more dear, more expensive, less driving will take place. And that choices will have to be made. Yet I see no discussion of choices. There is no discussion of the future. Just an analysis of the past based upon low (and still low) energy prices.

Analysis looking at past transportion usage, during a period of rising but still enormously cheap energy, has little preditive value, in my mind, to what will come.

It's useful to look at. But I think it tells us little and, other than pulling together some great information on transportation, the presentation does not at all argue or make the case that it has any predictive value.

Past results do not always predict future performance.

As mentioned yesterday.

YOU MIX BUS & RAIL AS "TRANSIT"

New Starts Light rail spending is in the range of $2 billion/year (federal & local, I gave the current federal spending yesterday at $1.25 billion/year with 50% match common).

This is the segment that I want to explode with $125 to $150 billion for Phase I.

You and others will note that I have NEVER promoted buses as a solution, other than advocating electric trolley buses to replace FF buses on busy routes.

Buses promote zero changes to the Urban form (TOD)(zero indirect energy savings), have high operating costs and fuel consumption /pax-mile varies from good to terrible. That is where "Transit" is in the US, with rail as a small afterthought.

In other forum, I have advocated increasing bus replacement cycles to 15 years from 12 years and using the savings for Urban Rail. In other words, shift part fo that $10 billion from bus to rail.

You have caught a labor savings (but electricity consuming) trend among agencies not to decouple trains between rush hours and run full trains sets all day. Easily reversed if/when the labor rate/electricity cost ratio reverses.

New lines do not have the passenger density of long established line ?

Big deal, I could have told you that ! There is zero TOD for new lines and ridership climbs over time. WMATA (DC Metro) has been counting on 2% to 3% annual increases for decades. They saw a spike this summer and flat growth since then.

IF WE BUILD OUT URBAN RAIL, MOST NEW LINES WILL BE LOWER DENSITY THAN MATURE EXISTING URBAN RAIL LINES

Boston will open a new (non-FTA funded, a rarity) diesel commuter rail line south of town (Greenbush http://www.cbbgreenbush.com/routemap.html I took a tour after ASPO Boston) in a few months. I forecast that it will have lower than average riderhship (compared to other Boston commuter rail lines) for a decade. I also forecast that the new line will steal ridership from the line directly to west, and the commuter ferry, thereby lowering your metric of pax/vehicle mile for Boston.

Greenbush was built with future electrification in mind, but several bridges closer to Boston have to be raised for all of the South Boston commuter rail lines to be electrified.

Obviously a waste of money (by your inferred logic) ! Spend money to build and then LOWER average pax-miles/vehicle ! WHAT A WASTE !

The 4 track Lexington Avenue subway in NYC is above nominal capacity at 600,000 to 650,000 pax/day. Near crush loads at rush hour. VERY cost effective ! I want to build the 2nd Avenue subway to take the load off of Lexington Ave., and attract pax that will not tolerate such crowding.

Obviously a waste of money (by your inferred logic) ! Spend money to build and then LOWER average pax-miles/vehicle ! WHAT A WASTE !

Other than the stolen pax from the line to the west and the ferry (they will travel to a new station for Park & Ride if it is closer) it will take people who would have otherwise driven into Boston. And it will add several thousand more daily riders to the "T"s Red, Green, Blue and Orange lines (some will walk from South Station terminus to work). Oddly, bus transfers may be added later by rerouting existing bus routes but walkups (~15%), bicyclists, Park & Ride and Kiss & Ride will be the source of riders.

The new Urban rail lines have the following in common (A few exceptions).

- Lower than than US average passenger density (I prefer pax/mile averaged over all miles, i.e tennysons).

- First year ridership is the lowest, going up almost every year after that.

- Higher ridership in their first year than the bus service they displaced.

- Higher than FTA projected ridership first year

- Lower operating costs/pax-mile than the buses they displaced. Thus pax/vehicle ratios 1/3rd or 1/4th of US averages are still more cost effective to operate than buses.

- Adding ridership to other rail lines in the system (Greenbush will add subway riders to the "T", but steal riders from commuter line to West). Thus new Line B added to new Line A will increase cost effectiveness of Line A. Same is true of Lines C, D, E ...

Systems work better than single lines. They feed into each other.- Roughly half of new Light Rail Lines are single lines. Denver (until a few months ago), Houston, Minneapolis, St. Louis (until earlier this year), Salt Lake City (until 2004 ?) More single lines planned in Seattle, Phoenix, Charlotte,.

- Streetcars carry fewer pax/vehicle than do Light Rail, and I think the two are combined in FTA stats. There several small touristy streetcar lines added in the last decade. Memphis, Tampa, Dallas, Kenosha. And the 24 streetcar Canal Streetcar Line in New Orleans. I suspect some dilution in # due to disproportionate growth in streetcar %.