Why We Drive

Posted by Stuart Staniford on December 13, 2006 - 10:00am

- The need to accomodate peaking or plateauing of global oil supply.

- Carbon emissions contributing to global warming

- Dependence on oil from politically unstable, especially Middle Eastern, sources

Although reasonable people can differ over the timing and shape of the oil peak (#1), only fairly unreasonable people now believe that we can continue to increase our CO2 emissions without severe consequences in the future (#2). And almost everybody agrees that we have a serious near-term problem with #3, since so much of global oil supply comes from parts of the world at risk of "regional conflagration", to use our new Secretary of Defense's term.

So what to do?

There are a variety of answers out there: more efficient cars, better land-use planning, more mass-transit, consuming less, switching to alternative forms of energy to name a few.

Recently, for reasons that will become clearer in future posts, I've been trying to come up to speed on transportation issues. I'm tentatively coming to some conclusions that I know a lot of people on this site aren't going to like. I thought I'd start putting them out there and see what holes in my argument folks can find.

Specifically, it seems to me that neither changes in land-use, nor changes in transportation infrastructure (transit etc), are terribly promising as approaches to the terrible trio.

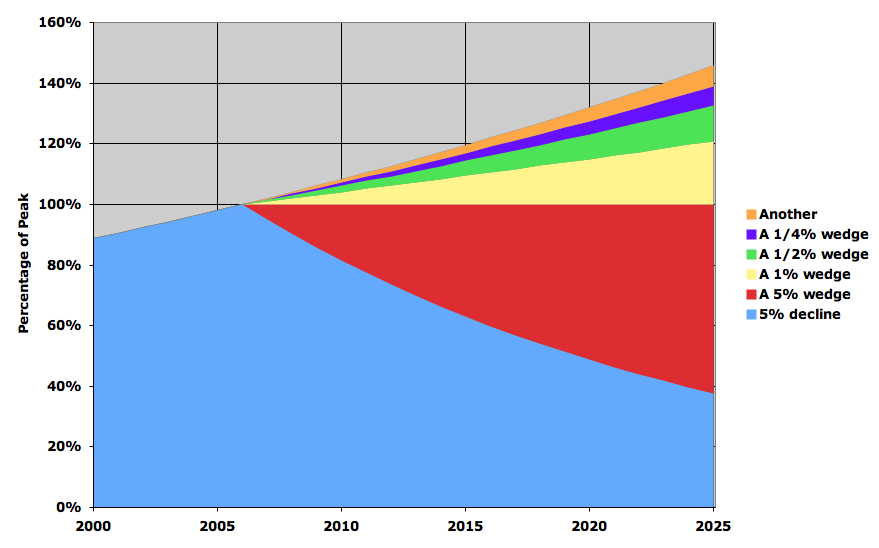

To put this in more concrete terms, I mean that these possibilities can only be very "thin wedges" in the pile of wedges that need to be stacked up between the declining oil usage or carbon emissions we would ideally like to have, and the accelerating usage/emissions we would be likely to get with continued business as usual. Roughly speaking, it appears to me that we need 6-8% of wedges (meaning enough things to get us from 1-2% annual increases down to 5-6% annual decreases in either emissions or oil usage). 5-6% is a reasonable number for illustrative purposes: it's what Hubbert linearization suggests for eventual global decline rates, it's the decline rate achieved in global oil consumption from 1979-1983, and it is also what the Institute for Public Policy Research suggests we do to carbon emissions to have high confidence that global temperature rise will not exceed 2oC. It's in the range of "pretty painful but probably not impossible". So in that context, a big wedge is a 3% or a 5% wedge. A small wedge is 1/2% or less.

The following figure illustrates the general idea (which can only be seen as a rough approximation, but good enough to be useful).

Firstly, let me, for the sake of completeness, justify why one would focus on transport, and specifically autos, if worried about any of the terrible trio:

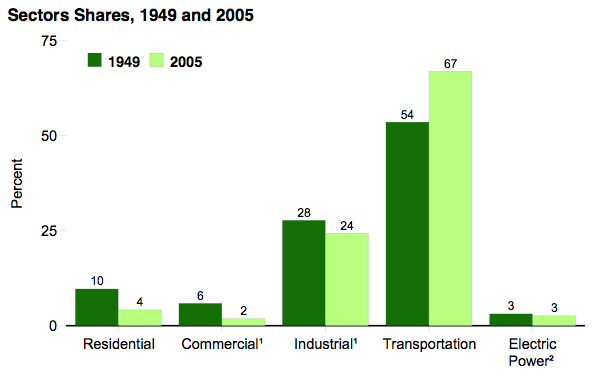

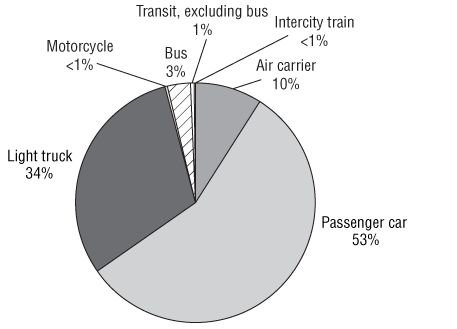

In the US, transportation represents 2/3 of our oil consumption:

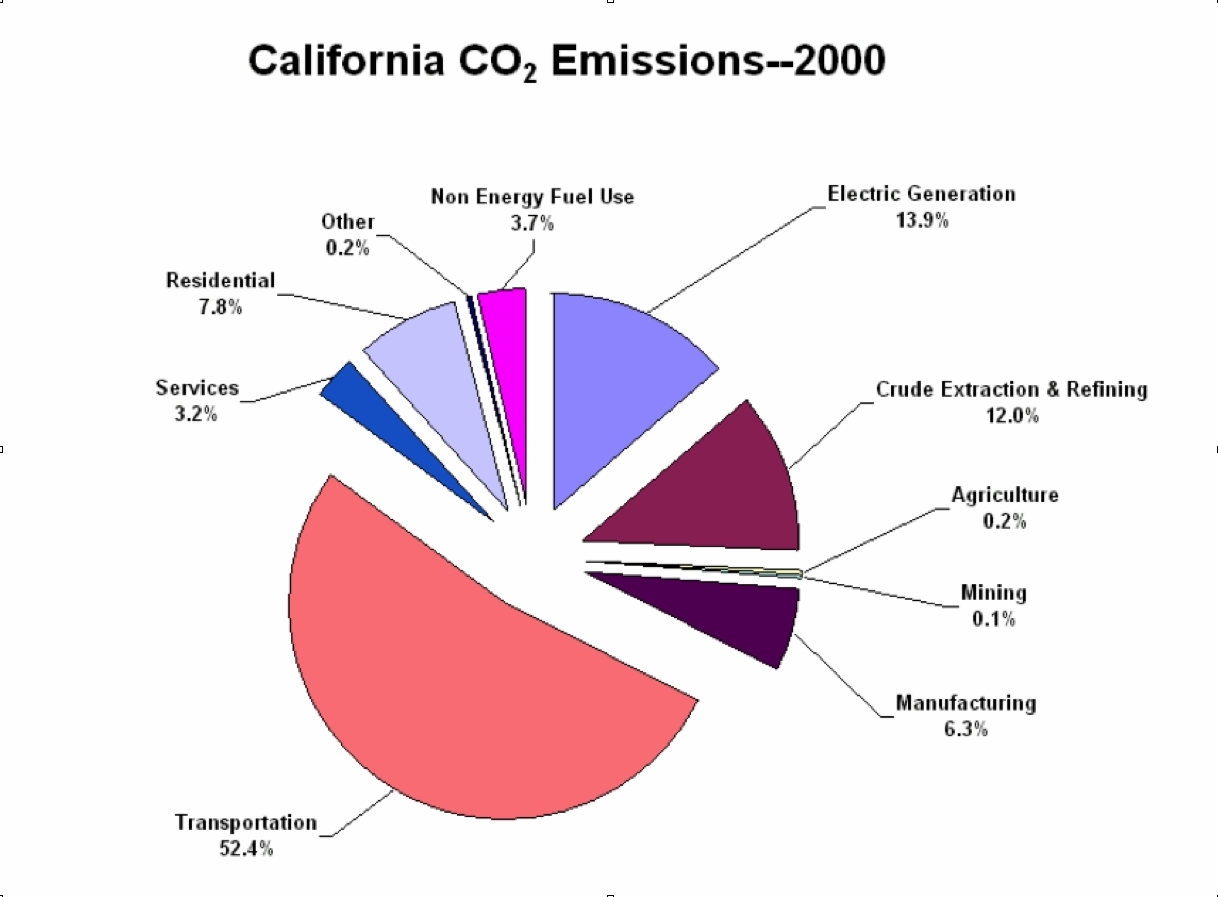

Of that usage, the majority (a shade under 2/3) is used by light vehicles on the highways. Similarly with carbon emissions. For example, here in California, where we just committed to cut carbon emissions 25% below business-as-usual by 2020, over half of the problem is transportation.

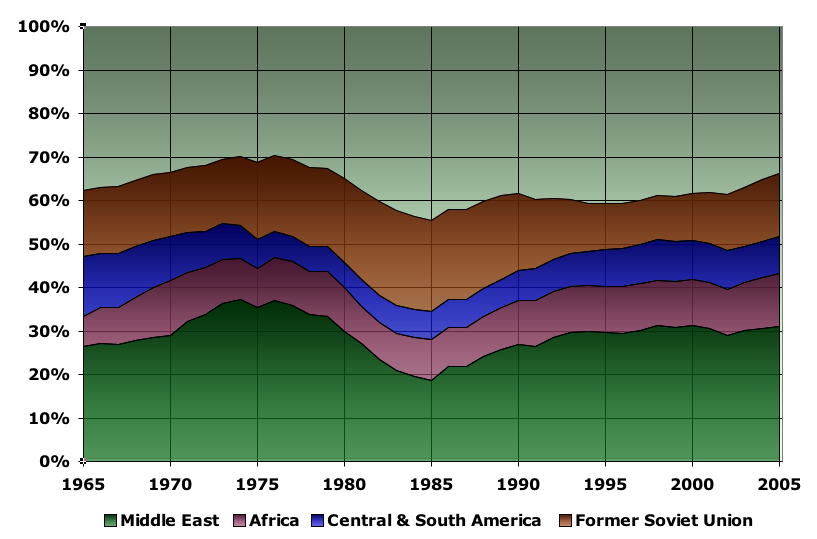

And then there is the energy dependence problem. 96% of US transportation is oil powered, and a large fraction of global oil supply comes from the following mix of less than ideally stable exporting regions.

As you can see, dependence on the unstable regions peaked in the 1970s, and then declined as North Sea and Alaskan oil were developed. However, now that those are declining rapidly, dependence on unstable places is worsening again. Since the only possible source of much new oil from stable places is now Canadian tar sands, and growth in that source is expected to be relatively slow, this situation is all but certain to get worse unless demand for oil can be shrunk.

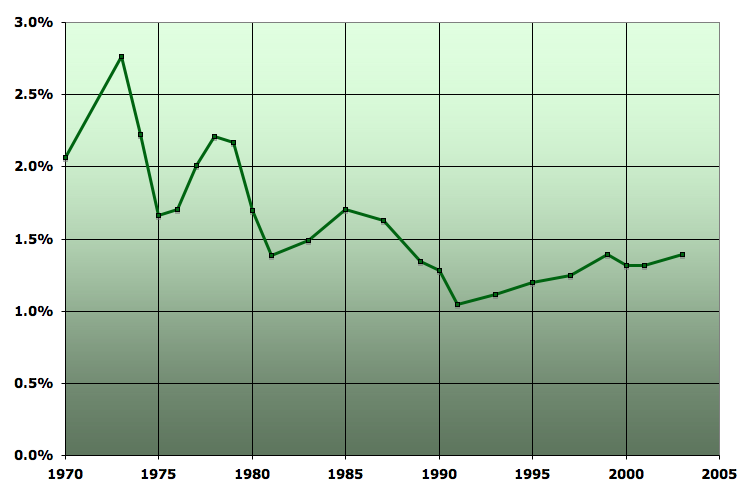

Not only is transportation critically linked with both oil and carbon emissions, but the quantity of transportation used (which can be measured by vehicle miles traveled) has historically been extraordinarily inelastic. It tends to increase inexorably year after year. Even the 1970s oil shocks produced only tiny 2% reductions in annual vehicle miles traveled.

Year on year percentage changes in US vehicle miles traveled, with GDP for comparison. Major oil shocks occurred in 1973 (Arab embargo), 1978-80 (Iranian revolution and Iran-Iraq war), and 1990-1991 (first Gulf war).

All in all, highway transportation is both the most important and the most intransigent aspect of our energy problem, so it makes sense to focus on it. We really love to drive. And I should say, since much of this piece is about the downsides and externalities of driving, that in my opinion, mobility is actually a good thing and a thing critical to a developed economy. There's a reason that kids can't wait to drive when they turn of age, and there's a reason poor countries use mules while rich countries use cars. It's the same reason why GDP and miles driven are highly correlated in the graph above. Being able to drive, or otherwise get around, allows workers to choose amongst more jobs, it allows contractors or salespeople to reach more clients, it allows employers to choose from a larger set of workers. In general, mobility promotes improved division of labor and economic efficiency, and thus wealth. Conversely, wealth allows more people to pay for more mobility, which they do with great enthusiasm all over the world.

We also just like the convenience of driving, as well as the aesthetic experience of piloting a couple of tons of steel with a few hundred horsepower of motivation.

So the question is how to have the upsides of getting around freely while cutting the downsides.

A popular answer with many Oil Drum readers, environmentalists, and a significant fraction of the urban planning community is mass transit. This has historically made intuitive sense to me since certainly these modes require less energy per passenger mile when operated at a decent fraction of capacity (and I commute by Caltrain many days myself). However, it doesn't take long with the data to make this look like a very unlikely solution to our terrible trio.

Firstly, as most people are aware, hardly anyone in the US is using transit:

As you can see, railroads, light rail etc are less than 2% of passenger miles. Buses are another 3%. Cars and trucks are almost the entire picture, with air transport the main long distance mode.

Not only is the share of transit ridership tiny, but it's been falling over recent decades.

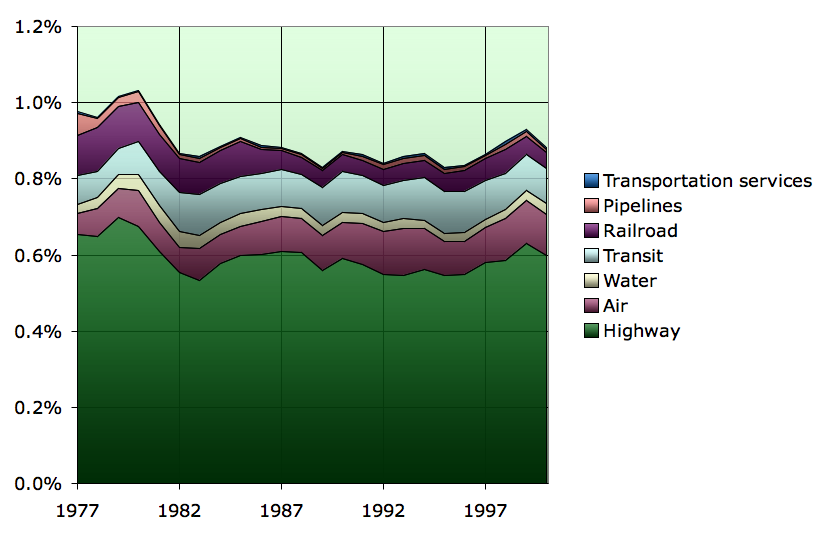

Ok, but maybe this is because, due to the evil car companies and oil companies, we underinvest in railroads and transit? Well, a few hours digging around in government statistics suggest otherwise. For orientation, here is the fraction of GDP that is expended on investment in transport infrastructure.

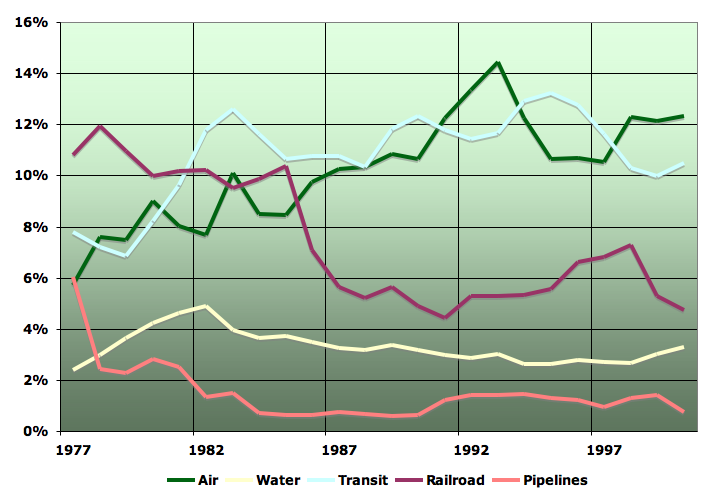

As you can see, we mostly spend a little less than 1% of our GDP on investment in our transport infrastructure, and that mainly goes on highways. However, look at this next graph. It shows the proportion of all transport infrastructure investment going on each of the non-highway modes.

What becomes clear to me is that the proportion of investment on transit and railroads is completely disproportionate to their ridership and has been for decades. Far from underinvesting in these modes, we are overinvesting. We invest comfortably over 15% of our total transportation infrastructure national budget into railroads and transit, and yet they are carrying only 1.5% of passenger miles. So each of those modes is roughly a factor of 10 worse than highways and airports in terms of the return (in actual useful movement of people) on the investment (in transport infrastructure spending). That's appalling and suggests that transit projects, at least taken in the aggregate, are basically a giant black hole for dollars that deliver little value. (Caveat: the long-haul railroad spending may have a stronger justification in terms of freight, but I didn't analyze that).

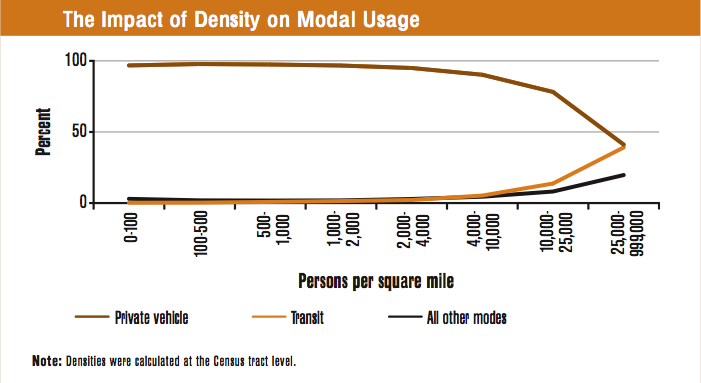

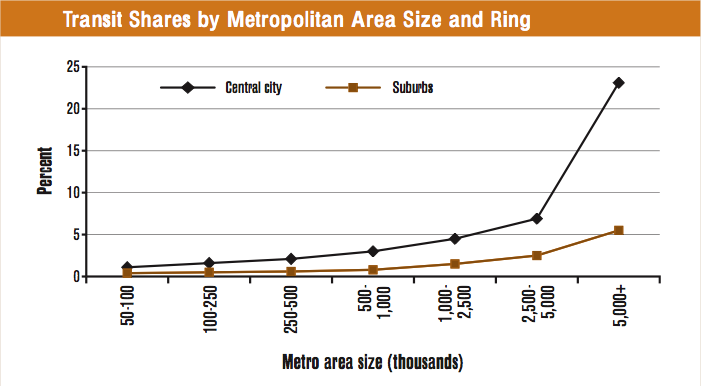

Ok, well why won't Americans take the train? Well, the rough answer is that it takes nearly twice as long to get anywhere (36 minutes versus 21 minutes for an average metropolitan area US commute according to The Road More Travelled). More specifically, transit critically depends on high population densities. There have to be enough people close to the station at one end of the ride, and enough interesting destinations at the other end of the ride, to make the ridership viable. It also helps if population density is high enough to make roads very congested. The following graph makes it amazingly clear:

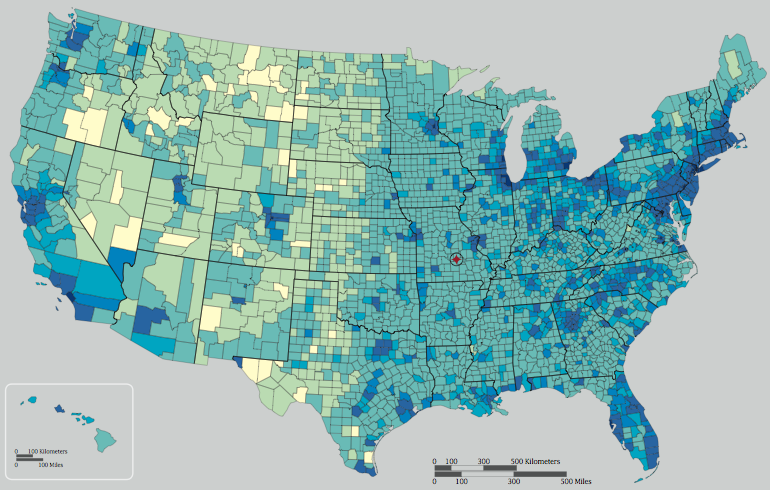

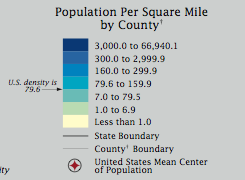

And, again as most of us know, America was not developed with high density in mind. The number of places with densities in excess of 10,000 people/sq mile is extremely small:

Thus as a result, transit share is extremely small except in the very largest cities, and then only in the city core:

So in short, transit is quite simply never going to work to reduce auto VMT significantly at any reasonable cost in the present pattern of US urban development.

Ok. But we should start fixing all this, right? It may have been that American sprawl is "the most destructive development pattern the world has ever seen, and perhaps the greatest misallocation of resources the world has ever known" in Kunstler's memorable phrase, but we can fix it, no? We can promote Transit Oriented Development, and all will get better?

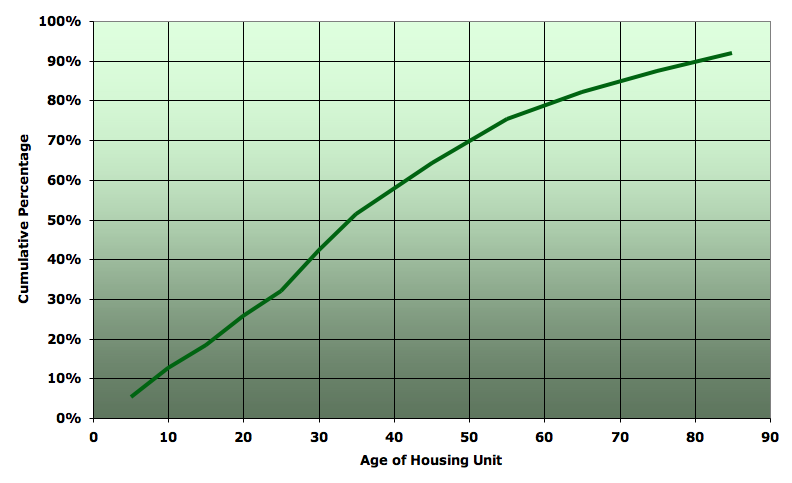

Only very slowly. The core problem here is the longevity of the housing stock. Here's the number of new housing units completed each year as a fraction of the existing housing stock:

As you can see, we only add a tiny and dropping fraction to the housing stock each year - now well less than 2%. Thus any changes we start to make in where we put future housing units will only make a very small difference each year. To get another look at the same things, here's the age distribution of US housing units:

The median housing unit is 35 years old, and many houses last a century.

To put this in wedge terms, consider the following thought experiment. Suppose, by politically draconian measures, we insist that all new housing development henceforward occurs such that the average driving of residents of those new units will only be half of the resident of existing units and we insist on retiring old units at the same rate we build new ones. That is, we basically force all new development to occur next to transit or in places of very high density. For this inconceivably herculean political effort, what do we get? Well, since about 1.25% or so of units turn over each year, we get a 0.6% wedge - not a major factor in our solution.

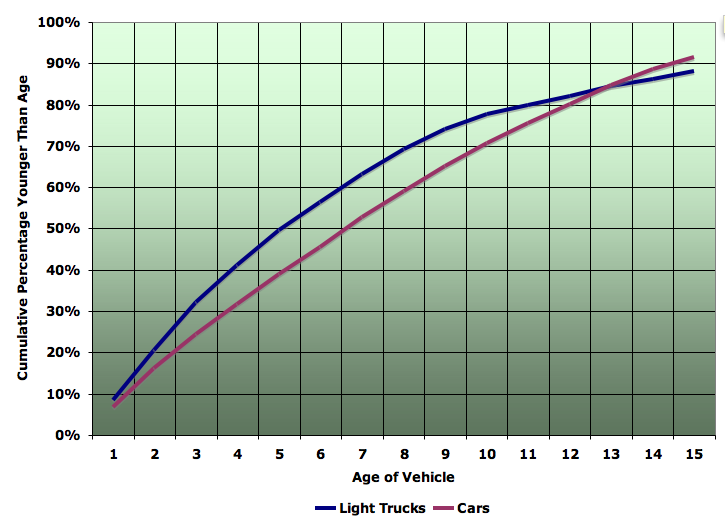

Contrast this with the situation for cars and trucks, which have a median life of only 5-6 years. Thus a herculean car replacement policy that insists all new vehicles are twice as fuel efficient as the old ones will create about a 4% wedge (ie something that makes a real difference). And this is why fuel economy responses were the leading demand-side response to the 70s oil shocks, and will probably be even more important going forward.

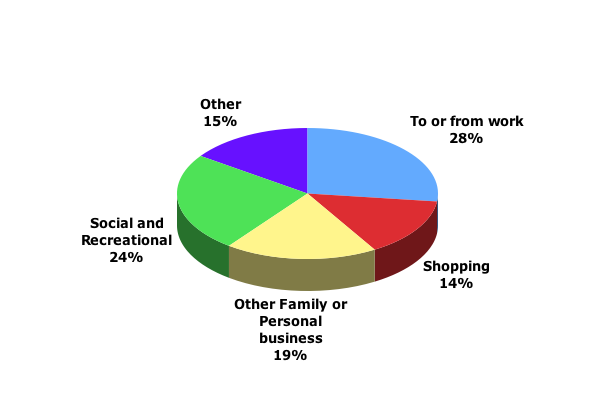

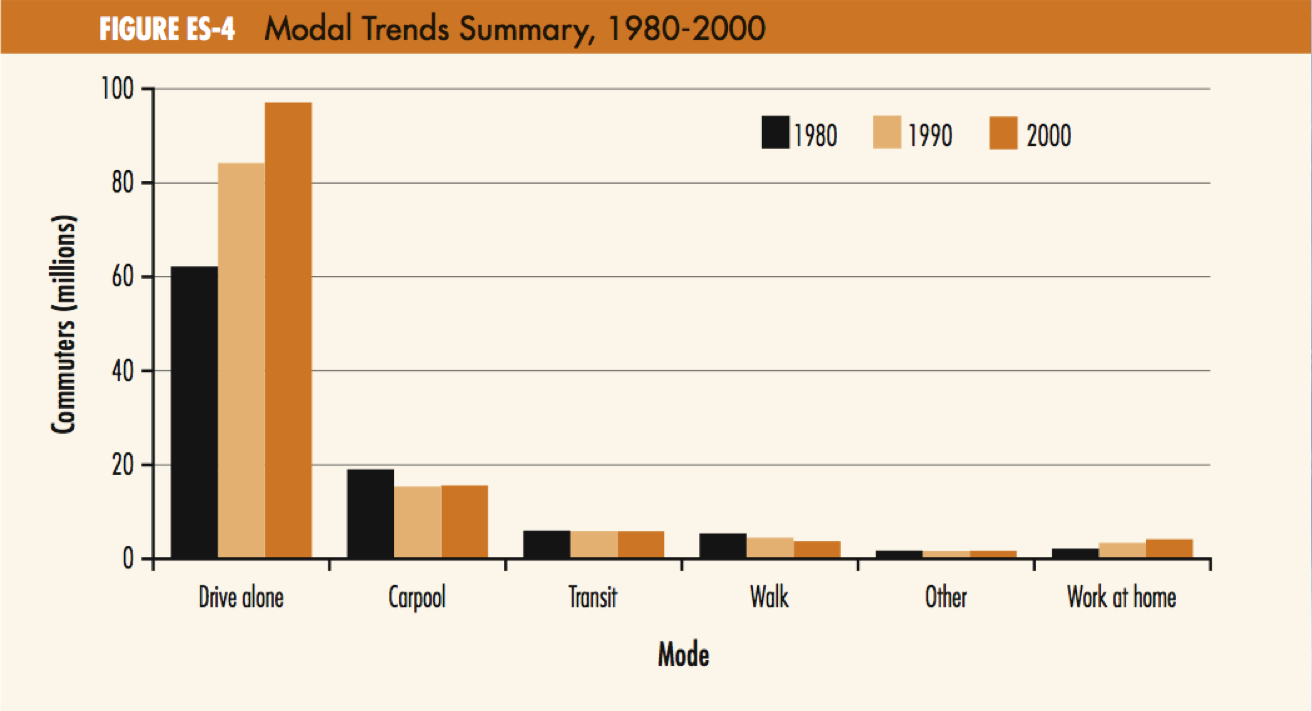

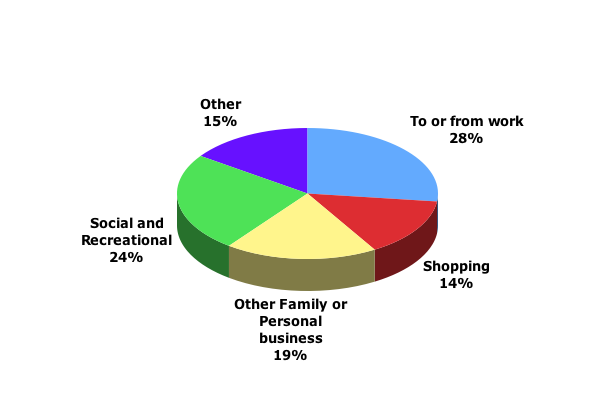

Finally, let me close with one last graph, which I finally tracked down: what are we all doing out there on the roads?

As you can see, the largest share of miles go in commuting, but social and recreational mileage is very close behind. Miles on personal errands and shopping are also significant contributions. So we would need to attack several of these categories to have much of an effect on vehicle miles traveled. More on that next time.

The problem around here is what to do with the car. I still must travel on some weekends, and as Stuart mentions above, the train and bus service take over seven hours for a three hour drive, and leave only once per day.

I also need a car for occasional business meetings. The local garages all have waiting lists for monthly parking, and you can get ticketed for feeding the meter in the same spot. Three of those tickets cost the same as monthly parking at a garage a mile away, so I guess I'll stick the car there and ride the Xootr over when I need it.

I lived in Montreal for a year before I got a car, I only got one after I got married.

Amongst cities where one could live (maybe) without public transit: Montreal, Vancouver, Ottawa, Toronto, New York, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco...

mostly eastern cities, all densely populated, mostly Canadian cities.

Even in Toronto, which has an extensive public transport system, it's basically no good if you live outside the 416 area) ie only half the population of the GTA (2.3 million/ 5.0 million) and I can tell you if you live more than 2 miles off the subway line in Toronto (most in the north of the City do) then transport is a nightmare. There is a reason the 401 Highway is one of the widest in the world.

Pre-K, 3 of the 5 apartments occupied in my "house" did not have cars. One bicycled to work, one was retired and one was an artist. Each made limited use of public transit.

Best Hopes for walkable enighborhoods,

Alan

Do we live in a densified coastal city? No, we live in public-transit-hostile Louisville, Kentucky.

That is why I purchased a used, cheap, small scooter. It drastically raised my gas mileage, but retains my 'mobility freedom' here in the Asphalt Wonderland. Obviously, the climate, no mass-transit, too few buses, and lack of urban density make this a good solution for me.

Bob Shaw in Phx,Az Are Humans Smarter than Yeast?

They spew out MORE pollution per minute than a fuel

efficient car. When I ballparked the figures a while ago my Chevy Sprint (52hp, 1L, 3 cylinder engine) put out less pollution than my 3hp lawn mower! It only takes around 10hp to cruise the highway and scooters, lawn mowers and other machines of that ilk have no pollution control equipment. A scotter also doesn't get much better milage than my Sprint (still on the road and gets >60mpg on the highway).

Of course we now use a push mower; but that's mostly been done away with by planting clover, wild strawberries (keeps the kids busy for many hours each summer) and using a neighbours electric push mower when we decide to hack it back.

Of course not using a pollution spewer unless you need to can make a big difference. In the case of our car the cost of purchase, maintaince, licensing, insurance and plates is many many times the cost of fuel (aprox 6,000 driving km/yr) and, for us, we'd not be able to move the kids on a scooter (the reason to have a car is to get the kids/family somewhere). I wonder what the cost of a scooter is? I'm cynical enough to think that the cost of insurnace would swamp the cost of purchase, fuel or maintaince.

Neighbours rent a car only when they need it - but now that they have a second child they're looking at buying a car. We thought about car sharing - but it doesn't work unless it's local - really local - as you can't just leave the kids behind while you go get a car ...

Cynically I think that when the #@$@$ hits the fan - that small changes like this are irrelevent. We'll be making big changes and fast. I'm just too cynical about rising debt, lack of savings and generally being overextended. Peak oil will deal a nasty blow when it's acknowledged and there is some panic.

This place in DC has a few:

http://www.skootercommuter.com/

Thxs for responding. Agreed, old two-stroke scooters are bad news--I would never own one of those smokers that is too underpowered to ride on city streets. The recent 4-stroke models are very much improved with computer-controlled programmed fuel injection and other emission goodies:

---------------------------------

Honda's Silverwing is powered by a 582cc DOHC parallel-twin, liquid-cooled motor, putting out a claimed 50hp (@7,500 rpm) and 37 ftlbs of torque (@6,000 rpm), Vibes from the 360-degree crank are kept at bay with twin balance shafts, fuel is injected, emissions are reduced by an exhaust air-injector and catalytic converter, and final drive is by CVT.

----------------------------------

400-600cc Scooters are tiny compared to the big Harleys and Honda Goldwings in engine displacement and acceleration performance. But if one just needs acceleration superior to most traffic--these scooters are sized just right. The big bikes and crotch rockets can accelerate like missiles--most car drivers have no appreciation of the unbelievable "get-up and go" these high power machines are capable of achieving. It is not necessary to have a big bike or crotch rocket unless every now and then you wish to 'goose it' for a thrill.

Bob Shaw in Phx,Az Are Humans Smarter than Yeast?

Click to enlarge photo

Cool picture! Looks like about 500 bikes--compare with the acres of real estate required to park 500 cars. Glad to see all the helmets. Covered parking is a smart incentive too.

Bob Shaw in Phx,Az Are Humans Smarter than Yeast?

found this today at the united nations website, its not just transport!!

http://www.fao.org/newsroom/en/news/2006/1000448/index.html

Livestock a major threat to environment

Remedies urgently needed

29 November 2006, Rome - Which causes more greenhouse gas emissions, rearing cattle or driving cars?

Surprise!

According to a new report published by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, the livestock sector generates more greenhouse gas emissions as measured in CO2 equivalent - 18 percent - than transport. It is also a major source of land and water degradation.

Says Henning Steinfeld, Chief of FAO's Livestock Information and Policy Branch and senior author of the report: "Livestock are one of the most significant contributors to today's most serious environmental problems. Urgent action is required to remedy the situation."

With increased prosperity, people are consuming more meat and dairy products every year. Global meat production is projected to more than double from 229 million tonnes in 1999/2001 to 465 million tonnes in 2050, while milk output is set to climb from 580 to 1043 million tonnes.

Long shadow

The global livestock sector is growing faster than any other agricultural sub-sector. It provides livelihoods to about 1.3 billion people and contributes about 40 percent to global agricultural output. For many poor farmers in developing countries livestock are also a source of renewable energy for draft and an essential source of organic fertilizer for their crops.

But such rapid growth exacts a steep environmental price, according to the FAO report, Livestock's Long Shadow -Environmental Issues and Options. "The environmental costs per unit of livestock production must be cut by one half, just to avoid the level of damage worsening beyond its present level," it warns.

When emissions from land use and land use change are included, the livestock sector accounts for 9 percent of CO2 deriving from human-related activities, but produces a much larger share of even more harmful greenhouse gases. It generates 65 percent of human-related nitrous oxide, which has 296 times the Global Warming Potential (GWP) of CO2. Most of this comes from manure.

And it accounts for respectively 37 percent of all human-induced methane (23 times as warming as CO2), which is largely produced by the digestive system of ruminants, and 64 percent of ammonia, which contributes significantly to acid rain.

Livestock now use 30 percent of the earth's entire land surface, mostly permanent pasture but also including 33 percent of the global arable land used to producing feed for livestock, the report notes. As forests are cleared to create new pastures, it is a major driver of deforestation, especially in Latin America where, for example, some 70 percent of former forests in the Amazon have been turned over to grazing.

Land and water

At the same time herds cause wide-scale land degradation, with about 20 percent of pastures considered as degraded through overgrazing, compaction and erosion. This figure is even higher in the drylands where inappropriate policies and inadequate livestock management contribute to advancing desertification.

The livestock business is among the most damaging sectors to the earth's increasingly scarce water resources, contributing among other things to water pollution, euthropication and the degeneration of coral reefs. The major polluting agents are animal wastes, antibiotics and hormones, chemicals from tanneries, fertilizers and the pesticides used to spray feed crops. Widespread overgrazing disturbs water cycles, reducing replenishment of above and below ground water resources. Significant amounts of water are withdrawn for the production of feed.

Livestock are estimated to be the main inland source of phosphorous and nitrogen contamination of the South China Sea, contributing to biodiversity loss in marine ecosystems.

Meat and dairy animals now account for about 20 percent of all terrestrial animal biomass. Livestock's presence in vast tracts of land and its demand for feed crops also contribute to biodiversity loss; 15 out of 24 important ecosystem services are assessed as in decline, with livestock identified as a culprit.

Remedies

The report, which was produced with the support of the multi-institutional Livestock, Environment and Development (LEAD) Initiative, proposes explicitly to consider these environmental costs and suggests a number of ways of remedying the situation, including:

Land degradation - controlling access and removing obstacles to mobility on common pastures. Use of soil conservation methods and silvopastoralism, together with controlled livestock exclusion from sensitive areas; payment schemes for environmental services in livestock-based land use to help reduce and reverse land degradation.

Atmosphere and climate - increasing the efficiency of livestock production and feed crop agriculture. Improving animals' diets to reduce enteric fermentation and consequent methane emissions, and setting up biogas plant initiatives to recycle manure.

Water - improving the efficiency of irrigation systems. Introducing full-cost pricing for water together with taxes to discourage large-scale livestock concentration close to cities.

These and related questions are the focus of discussions between FAO and its partners meeting to chart the way forward for livestock production at global consultations in Bangkok this week. These discussions also include the substantial public health risks related to the rapid livestock sector growth as, increasingly, animal diseases also affect humans; rapid livestock sector growth can also lead to the exclusion of smallholders from growing markets.

My scooter is an e-max and it runs on electricity generated by wind power from the grid. I also have 4 small solar panels that I use to recharge the batteries in the summer.

The only bad thing about the scooter is that I do not use it much in December or January because of the weather here in Utah. When the weather is bad I drive the Prius to work. If they start selling a plugin version I will be first in line to buy one of those.

The black and decker electric mower is a good solution for the lawn duties along with an electric trimmer.

I always liked the looks of the Chevy sprint, to bad GM does not still build new ones.

If we can't get the suburbs back to town, why not bring town to the suburbs? In my estate in Coventry ,UK, I notice we have very few amenities within walking distance. This is because the town planners who designed it didn't believe in mixed-use. I think there might be some mileage (he he) in building small local centres at strategic points in suburbia with shops and workplaces. It'll mean that people have the option to live closer to work and have a walk or a much shorter drive to their local shops. These centers could maybe be linked together by freeway, tram or rail.

This might be a way to avoid Kunstler-burbs, basically by bringing some granularity to existing low density suburbs. These new "town centres" might contain higher density housing and may attract locals to live there, abandoning the most hard-to-reach 'burbs in an energy shortage.

I think that this will be the cheapest and easiest way to the future. It gives people ways to localise.

- What will stop people using personal automobiles for commuting purposes

- What will stop people using personal automobiles for social and recreational purposes

- What will stop people using personal automobiles for shopping

The obvious, but politically nigh-on-impossible, answer is to tax gasoline to a level that is so painful that people have no choice but to use the bus, train or other (where such exists) to commute, reduce their social and recreational motoring, and plan their shopping trips to buy as much as produce as they need for as long a period as economically practicable.Aside from the difficulty of finding a politician to back such a vote-losing proposition, another problem with the obvious solution is that it is a burden borne foremost by the poorest people first, and thus may be seen as a tax predominantly on the poor. Arguably, this is not in itself a problem as long as alternatives are available at a reasonable price and utility.

It may therefore make sense to use a significant proportion of increased gasoline taxes to create and subsidise a more efficient, reliable, pratical, cleaner and cheaper public network of buses, trains etc. In this way, people get financially squeezed out of their cars but ultimately benefit financially and otherwise from a better transport system than previously existed. In turn, richer people who elected to continue to use private transport would essentially be directly subsidising the poorer masses who are forced into using public trasnportation.

These are just some knee-jerk thoughts to Stuart's post. Interested in thoughts about practicality or otherwise of the above, as well as ideas about the sort of public transportation required. As an example, I believe that local networks of buses (similar to school bus system) would be required to deliver people from home to station and station to place-of-work.

I believe that even higher taxes would force people out of their cars and am not in principle opposed to this, as long as a substitute service is provided with the taxes raised. This means more bus, train, tram and underground services operating more efficiently over a wider area (such that door-to-door service is almost available as with private cars) at a lower cost than at present.

However, on the whole, you are right, the LOWEST hanging fruit in conservation in the US is a transition to smaller more fuel-efficient vehicles. That would however necesitate a change in the non-negotiable way of life.

The point I'm making is that high or low taxes are just a matter of historical expediency, not sound economic management by the government. In the UK so called "green" taxes have actually fallen since Labour came into power 9 years ago and the pre-budget speech by Gordon Brown contained just a couple of pathetically mild measures which will make no difference to anything. The US political system might be broken, but no more so than in the UK. Economic growth is still seen as the number 1 priority vote winner and the environmental is more of a lip service thing.

The 'escalator' was a tacit agreement by both parties that petrol duties could be raised by inflation + 3%.

The logic was simple. It was easier to raise taxes on petrol, than on VAT or income tax. The UK raises £20bn pa from petrol taxation, a very large sum, and has some of the highest petrol taxes in the world.

In 2000, the straw broke the camel's back. Petrol crept over the 80p/ litre level. A group of truckers, farmers, and others blockaded the fuel depots, sparking a popular revolt, and a nearly complete shutdown of the country for 3 days.

Since then, guided by Tony Blair's grasp of what is acceptable to the common man (and the Daily Mail) and in particular the key swing voter 'Mondeo Man', a suburban dwelling, car driving bloke, the Chancellor has not been allowed anywhere near the motorist.

Not about cars for sure, but involved in the small problem of transport in general:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/scotland/north_east/6173795.stm

Aberdeen Airport is to be extended to enable transatlantic flights. Cost? £300 million

Should be ready by 2015.

Will make a nice skate board park from 2020 onwards.

For several years I drove a downtown parking shuttle where people could parked for free and rode for free. The state provided a per passenger subsidy to the transit system. Ridership was so high on the free shuttle that it was the only route that made a profit for the agency.

If you want to get people out of their cars onto collective transport the fare matters little here but it helps to have a dense schedule, preferably every 20 min or less, good cleaning of the wehicels, air conditioning and they are for some strange reason more attractive if they run on rails.

The income from fares is usually about 30-50% of the total cost for collective traffic in Sweden. The tax subsidy is large :-( The only collective traffic running withouth subsidy are the main rail routes, private bus companies between some large towns, airport shuttles and air travel from large airports.

Cleaner air and streets not full of cars, for example, or being able to enjoy an evening downtown without having to worry about driving home, or the children who can ride the system for free or a very small fee, or the access to the city for people who live in smaller towns without a vehicle (that one tends to have the merchants support him very strongly, by the way).

In other words, much like the parks and playgrounds, or the museums and theaters, as long as access is broad enough, such things are worth having, even if they don't pay for themselves in a free market sense.

- What will attract people to alternatives to using personal automobiles for commuting purposes?

- What will attract people to alternatives to using personal automobiles for social and recreational purposes?

- What will attract people to alternatives to using personal automobiles for shopping?

The key is in meeting commuter expectations rather than thwarting them.One aspect, which has yet to receive much discussion in this thread, is pricing other than fuel. One of the reason that people in the U.S. drive so much is that it is relatively inexpensive to drive and park a car. As the total cost of commuting increases - fuel, insurance, tolls, parking, congestion pricing, etc. - people will have more incentive to look at transportation alternatives. Certainly, when I worked in downtown Portland, the main reason that I rode the bus was that a bus pass was cheaper than parking. Conversely, working in downtown Austin today, my parking is provided free of charge, and I have less incentive to use the less convenient transit.

One of the big issues currently being debated in Texas is how to pay for our roads. The governor has proposed a major toll-road building program that has met with significant public opposition. The other possibility is to increase the state gas tax. Regardless, driving costs in Texas, already the state with the highest transportation costs, will likely be going up.

Returning to the original post, flaws and gaps in the data relied upon undermine the conclusions. For instance, the Passenger-Miles of Travel by Mode chart omits any categories for bicyclists and pedestrians. Now, these will be small percentages, but they need to be included. Also, as pointed out by others, when measuring trips rather than miles, these modes will rise in significance, particularly for the major urban areas. For instance, I just returned from walking two blocks to lunch: low mileage but two trips.

I also question the methodology used to generate the Summary of Travel Trends pie chart used to open and close the post. Given the breadth of the other four categories, I cannot begin to imagine what trips are included in the "15% Other." This raises questions about how the data was gathered and interpreted.

In closing, VMT can be reduced through a combination of pricing, land use, and transit, but the potential reduction will be partially offset through shifts to higher mileage vehicles.

While I think there's a lot more elasticity of the social fabric built in before we proverbially 'resort to cannibalism,' (or any other image of Doom), there's a hell of a lot more to be done than simply requiring lighter hybrid cars, or spending a fraction of a percent of GDP on trains.

EVERY aspect of how we live needs to be examined from a systems perspective, with an eye towards saving energy. This will not happen at The Speed of Congress - being slower than any impending catastrophe, including a peak 30 years out.

The only way to make it happen is to make gasoline energy a significant percentage of the cost of driving(rather than the silver-plated Peltier-effect cupholders), to make natural gas energy a significant percentage of the cost of heating a house (rather than ammortization of the fake fireplace you bought), to make bombs cost more to produce than the pilot that drops them.

The only way to force this level of attention is a free market approach, combined with subsidies for durable systematic improvements (rather than consummables).

You should be able to drive around in that Hummer all day long if you can afford it, and you can offer me just compensation for taking more than your share of the pie, and shitting in my air supply.

So here's the plan:

We tax energy. Heavily. At the source. To levels comparable to Europe - which would force severe, rapid change in the US (yeah, we're not Europe, I get it). The tax has two parts (let's call them equal for sweet, light crude): Pollution, and Energy Security. Energy security is levied on imported energy. Pollution is levied mostly on GhG equivalence, and minor amounts on toxic portions of coal, oil, uranium, etc.

Taxing is done at the heavy industry level - refinery, mine, powerplant, distributor - whatever. It trickles down in a way that cutting taxes for the rich never did.

No fucking carbon trading. No paying people for trees that they didn't cut down, oil they didn't buy, or trips that they didn't take. No rationing. No exemptions, deductions, or allowances.

Then, we give it all back in a rebate at the end of the year. One equal check per tax paying US citizen.

This handily solves the political problem (it's minimally progressive, even, as the rich spend more energy), it's enforceable, it caters to the isolationist masses which teem after a major war, and it creates a market for energy saving solutions, changes in culture, and relocalization that nothing else can possibly do other than a postpeak drawdown.

A major energy tax is necessary, but it's not enough...

----------------------------------------

There was a question asked in a HuffPo article a few days ago - what would you spend, given one free Act of Congress, on sustainability and solving Global Warming, and how much of it would go where.

I think around 2% of GDP - $250 billion a year is necessary in government spending, on top of the energy tax mentioned above.

30 billion / yr to create a national inter-metropolitan area highspeed maglev network, designed to obsolete the long-haul trucking industry, the airline industry, and some of the long-distance features we currently require in automotives. Anything should be haulable from Boston to San Diego in 12 hours. Existing lowspeed rail networks form a last-mile approach, and could be reactivated commercially if such a system were in place. Stations are under major airport terminals every 100 miles or so. Shades of the Interstate project.

30 billion / yr in matching funds for electrified urban and semi-urban rail, starting with Alan's projects.

20 billion / yr in incentives for wind energy capacity, mostly using emminent federal domain to defeat NIMBYism

10 billion / yr goes into a fund that purchases progressively larger, progressively cheaper solar installations in a non-bidding scheme: "I'll buy 1GW at $2/watt, then 1.5GW at $1.80/watt, then 2GW at $1.60/watt" Solar energy is noncompetitive without major cost improvements.

20 billion / yr goes into subsidized energy efficient home and commercial systems: Mostly insulation + insulation retrofits, multipane windows, shutters and windows that open/close, better lighting, weathersealing, cheaper solar thermal solutions, greywater recycling systems... the list goes on for a few pages. Intended to be exceeded by private sector activity, but this provides a leg up.

20 billion / yr goes to giving the UN teeth to fight its own wars by consensus rather than using our oil, in combination with a major drawdown in US military forces designed to allow this much spending on energy. We attacked Iraq, while letting Darfur burn, North Korea glow, Al Qaeda open branch offices, and the Taliban grow heroin. An internationalist military bent (call it what you will) is simply much cheaper in energy, political willpower, and human life than being the world's only military superpower, on hundreds of billions of dollars of national debt a year.

5 billion / yr goes into a new energy research organisation resembling DARPA which provides numerous small-scale grants and overview for scientists and inventors doing research on sustainability, energy, etc.

20 billion / yr on 3G nuclear fission.

10 billion / yr on nuclear fusion.

10 billion / yr on undeveloped biologicals (crops lacking lobbyists, but suitable for growing in the US), with an emphasis on algal biodiesel, and secondary emphasis on jatropha and pongammia biodiesel, and gasification from a wide variety of sources.

1 billion / yr on whichever ends up being higher ROI and higher energy / pollution ratio: CTL or Oil Shale.

5 billion / yr goes into providing cogen systems for heavy industry, with utility hookup: there are a lot of waste heat sources out there, and a lot of hot water heaters, radiators, and steam turbines to be spun.

2 billion / yr in federal assistance to science & engineering students

1 billion / yr to implement geothermal + hydro wherever possible.

The rest goes into a program that shifts in allocation: the first year, all is put into protectionist trade measures to keep manufacturing here and cushion the economy. The next year, 10% goes to energy production capacity improvements based on best-available technology improvements, the next year, 20% goes to capacity. By the end of 10 years, all of it goes to capacity.

---------------------------------

This is designed to be implemented in 2008 by a PO-aware tri-majority Democratic president, and to have enough momentum that A) it would achieve energy independance and a major reduction in carbon footprint before 2020, B) it would accomplish a major cultural shift, and C) it would be impossible (fight oil lobbyists with wind/nuke/etc lobbyists) to completely dismantle given a change of party in ensuing elections.

IF there is a goal that they will buy into, they can tax themselves.

IF they accept that Peak Oil is a reality and $4.80/gallon is just the beginning, then higher gas taxes for a "way out" are supportable, IMHO. Not overwhelming political support, but doable.

Clinton did manage a 4.x cent gas tax BTW.

Alan

He tried to get a 50c tax in 1993, and Congress cut it down to 4c. And what happened to the Democratic party in 1994? Oops.

I think HOT lanes are probably a more promising approach than a gas tax. Convert existing HOV lanes to HOT, and then as people get used to them, make more from the regular lanes by degrees. I think that has more chance of working because people might see advantages for themselves in the existence of the HOT lane (ie that they can get somewhere fast when they need to if they are willing to pay). However, I imagine it will still be a slow and hard-fought process.

I think raising CAFE is more promising again, because voters are more willing to put the problem on the auto companies than take it on themselves. However, Detroit will no doubt push back mightily. But there might be enough political will at the moment with all the concern over energy independence.

I think the politicians have their marching orders and need their feet held to the fire until they get it done.

What I'm looking for her is a tipping point when it becomes so clear that oil is a loser that we start to change how we do things in a big way.

Source

Another big wedge is available in the USA through switching vehicle use from SUVs and pickups to passenger cars. Light trucks make up approximately 50% of new vehicle sales in the US but most are used for tasks like commuting and transporting the kids to school. CO2 emissions and fuel consumption are directly related. Driving an average new light truck to the supermarket uses about 42% more fuel than driving an average new car. The savings from switching to a small, fuel-efficient car are even greater.

Doomer

Social & Recreational -- 24%

Fill'er Up For

Happy Motoring!

I believe when Jim uses the phrase the greatest misallocation of resources the world has ever known, we now begin to grasp what he really means.

Kunstler's words struck home with me a long while ago and I agreed the first time I read them. Further, I'll state that I think homo americanus-automobilus is doomed to extinction within a century at the most.

There is nothing wrong with recreational driving. There is a lot wrong with using 5.8l 300hp engines to move 2 tons of sheet metal penis enlargement to do it.

This is news. Where did these five year plans with the 'least amount' of energy/matter input occur?

There is nothing wrong with markets playing the real-time equivalent of these idealized controlling instances. We know it works... up to a point. Markets need to be regulated to stay within reasonable bounds and be left alone to sense trends that are not appearent to any logical analysis. There are judgement calls here.

In the end ... the oil markets will regulate the SUV out of existence. It will come at a very high cost but it will come. One could do the same thing at a much lower cost by using regulatory mechanism like the gas tax. Oh... actually... most of the world has. Only the US is lagging behind.

Bullshit, and especially re the freezing and starving, except for the latter ONCE in China in the early fifties (and even that is disputed, e.g. by William Hinton).

The system 'worked' extremely well. In the USSR/DDR, one did not pay, e.g. mortgage costs, rent, or even utilities. Imagine, you Yanks: a society where one does not pay the banker, or the landlord, or even the utility company! GASP! Where money is largely 'tokenistic', some pittance you give up to get on the tram (Orlov). It's entirely against the natural order! It is IMPOSSIBLE! Surely no modern society could ever have done such a thing!

Uh-oh, flame war time. 300 million brainwashed Americans about to tell me how everyone in the Soviet bloc was starving and freezing, just like the Western press has always told us!

Propaganda notwithstanding, the Soviet bloc had fully functional industrial societies with well-fed populations. (except Romania).

So eff off with your stale anti-Communist propaganda.

By the way, one of the largest 'planned economies' on Earth is the Pentagon. And I think it does rather well, except of course when it comes to fighting :)...

No flames from me. I think it entirely possible to do the same in America if TPTB can be convinced [and that is the difficult part!], that it is an excellent way to help reduce violence postPeak. But I am not enough of an econ-expert on the topic of a 'gift economy' to know how this should be designed and implemented.

I think this is what Richard Rainwater will do to get his South Carolina neighbors to rally around to build a large communal survival habitat.

Hey, Don Sailorman! Are you there? Care to comment?

Bob Shaw in Phx,Az Are Humans Smarter than Yeast?

being from Germany, I can maybe add some little aspects to your glorious communism that were observed at the time:

- Yes, nobody starved.

But:

- In general, the economy didn't work very well. When Germany was reunified, it turned out that most of the East-German industrial base had been systematically worn-down from the already low peak it achieved after it had half-way recovered from the destructions of WW2 and the disinstallations the Soviets did.

- The environment generally suffered heavily under the emissions of long outdated technology and complete disregard for the health of the population.

- Not having to pay a landlord, almost equal incomes, little private whealth and all the other glorious achievements of East-German socialism (it has never been real communism!) resulted in a lack of initiative and care for the common possessions. Example: I live in a part of the former East Germany and it took all the years since 1990 to redevelop most of the ruined building stock to any reasonable level.

Having seen all that, I strongly advocate using market forces for most aspects of resource distribution but strongly reigned in by far-sighted government regulation.Cheers,

Davidyson

I agree with your statements, but I have one question: How are we to get "far-sighted government regulation."? Most elected politicians look into the future only as far as the next election.

To deal with peak oil and global warming more government regulation will be needed--I don't think there can be any doubt as to that conclusion. However, my guess is that until there is a major crisis (say equal to the Great Depression), the U.S. government (and most other governments) will react with feeble legislation and regulation and only incrementally.

I don't want a major economic collapse. I don't want a major war. But one or the other will probably be required to make major changes in a society as car-centered as is the U.S.

there are some examples of fairly far-sighted government regulation, as in the catalytic converter regulation or the ozone hole chemicals regulation.

However, these were certainly easy compared to the challenges of peak oil. So I agree that we will probably not see any timely reaction from the governments.

Pity!

Cheers,

Davidyson

And they had prison camps, and tortured and murdered opponents.

And they built a wall around it and shot anyone who tried to get out.

Soviet Communism was amongst the most odious regimes ever invented by the human race. Fascism was arguably worse, but Marxist-Leninism did more damage to more people, by the sheer virtue of being around much longer on the face of the planet.

- Australian aborigines - the (Protestant) British Empire

- North American aboriginals - see above, also the United States (no Catholic President pre 1960)

(the French married them, the English and Americans slaughtered them-- Riel was a Catholic priest before he was a resistance leader)- the liquidation of the Kulaks and the Great Purge in 1930s Russia (say 12-15m dead) - Stalin

- the Great Leap Forward in 1959-60 China (say 10 million) - Mao Tse Dong

- Genghis Khan (20 million, 30 million? who knows?)

- the Holocaust (6-7 million)- the Nazis

- Japan in China in the 1930s (Rape of Nanjing etc.)

None of these can be wholly, or primarily, or indeed at all, awarded to the Catholic ChurchWe can count against the Catholics what happened when the Spanish conquered South and Central America. Although of course disease did much of the work for them. And latterly, the Church took responsibility for protecting the natives against colonial depredation.

We could count the Belgian 19th century genocide in the Congo, but since Belgium was an independent nation, albeit a Catholic one, I'm not sure how well that would work.

Which particular atrocities were you seeking to balance against those?

The church had and in many places still has a very big cultural influence: keeping the disdain for jews alive and thereby providing ground for countless pogroms and similar policies, providing a moral ground for the domination and exploitation of heathens, blocking the spread of a responsible attitude towards family planning, etc.

The goal of the church in the colonies was simply to expand its power, whether by sending priests after the conquistadores or missionaries before them - as long as the heathen were converted, and adopted European culture everything else didn't matter (remember the debate of De Las Casas vs. Sepulveda). The colonization of Africa was a similarly messy affair of economic exploitation, and do you really think that the humanity of the plantation masters depended on the flag on their villa?

We need to see the church (any church) as it really is: an organisation that, in the first place, seeks to gain power and to perpetuate itself.

Humans have an (apparently) innate need to seek the spiritual.

That tends to lead to organised religion.

If the motive were entirely self centred, I don't think religion would thrive in the way it does, in human affairs.

And nations without strong religious institutions (I am thinking post communist China and Russia) have their own pathologies: a kind of mindless selfish materialism.

"Well fed" if you ignore the Ukrainian terror famines and crop failures in the 'stans, not to mention the Aral Sea catastrophe.

As for not freezing, that was mostly 'thanks' to district scaled hot water distribution systems that were exceedingly wasteful.

The Soviet Union had all the energy wastefullness and profligacy of the United States, and none of the fun.

http://www.lightrailnow.org/features/f_lrt_2006-05a.htm

I also have a $125-$150 billion dollar list of "on-the-shelf" Urban Rail projects that could be started in 1 to 3 years. A second wave of $300 to $500 billion in 5 to 8 years (start construction, not complete).

Now, I assumed "pre-Peak" conditions (somewhat rising oil prices) in my "10% savings" projection. Raise oil prices, put 50 mph speed limits on, change gov't policies and I can "promise" 20%, not 10% savings ! Perhaps even 33% of total US oil consumption in ten to twelve years.

I look at the less than 1% drop in US oil consumption with recent oil price increases and I see economic recession/depression as the only way to get even -2.5% to -3% annual drops in oil consumption with "free market" responses. Start considering -8% compounded for a half dozen years and {insert image of computer blue screen}

IMHO, post-Peak Oil will not be a stick, it will be a hammer !

The only refuge from this destructive hammer will be clustered around non-oil transportation, using little oil & NG for other needs. We may be in a situation where "extraordinary" events unfold and previously unthinkable choices are made.

I live in post-Katrina New Orleans and my sense of what is possible is much greater than most.

I look to history. The US totally changed our urban form from ~1950 to ~1970. We killed (or at least marginalized), with very few exceptions, every one of our downtown commercial areas ! We invented new urban forms (strip malls, drive-in everything, regional malls, interstate highway development) ! A truly remarkable "achievement".

We also built, largely with "coal, mules and sweat", subways in our largest cities and streetcars in 500 cities, towns and even villages, in twenty years from 1897 to 1916. No advanced technology, very little oil till towards the end of the period, but astounding results !

IF we start now, even with modest goals, this will enlarge and speed up a later, much larger transformation. Spend 85%, and not 15% of our transportation capital on electrified rail, muc of the rest of buses, HOV lanes, etc. Starting from a slow walk is much easier than from a recliner, asleep.

I want to start walking in the right direction ! Then we can start running when we have to.

Best Hopes,

Alan

Here in London, lack of housing is has caused a huge runup in pricing so I wonder if pricing could be a mechanism to force the closedown of suburbia? However having said that if the cost of transit to/from work becomes a major major factor then we might be on the verge of city collapse anyway...

Regards, Nick.

I have a friend, a college profesor, who elected to stay in town even though they wanted a bigger yard for their three boys. When they figured in the cost of having to go from 1 car to 2, they realized ir just didn't make sense (He walks to work). Now they live in a slightly bigger home with a slightly bigger yard that's one block from a city park and they're still a one car family. If Americans really thought about it, it doesn't always make economic sense to live in the burbs. Perhaps in hot markets like Boston, but not in your average midwest city.

I think status is still a big driver in the continued growth of suburbs, plus suburbia is needed to maintain the large corporate home builders. A large behemoth like Toll Brothers cannot survive doing urban redevelopment- tucking in a house on a empty lot here, building a 12 unit condo building there. They need 400 acres for a 800 home development to sustain the machine.

Where in the world do you think everyone is going to go?

The cities are already crowded. Sure you could build up, but it isn't cheap. New construction in Boston or Cambridge (the city) routinely goes for $400k+ for a 1 bedroom. And I know here in Boston there are tons of historic districts that fight any new addition to the skyline.

There's no way the suburbs are going away. I could certainly see a little reconfiguration with commercial and retail being blended in, but this vision of empty housing developments as far as the eye can see is crazy. The cars people drive will radically change (smaller/lighter) long before you see any sort of mass exodus from ther suburbs.

I think we're going to crowd in together, like they do in Third World nations.

Here in the U.S., we laugh at the idea of taking in a boarder to make ends meet. We pass laws to keep immigrants from crowding 15 people into a small apartment. We consider it practically child abuse if each kid doesn't get his own room.

That will change. In the Great Depression, tent cities sprouted near cities, full of people looking for work. I think we'll see that again.

The problem of insufficient housing infrastructure is a problem only if you think every family needs their own apartment...or 3,000SF McMansion.

308 sq ft (about 31 m2)

http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2006/03/04/HOG86HFNDU1.DTL

Best Hopes,

Alan

But if my family needed a place to stay - my parents, my grandparents, my sister and her partner, my cousins, etc. - I would welcome them with open arms. I think most people would, if things were Great Depression-bad.

And if prices keep getting higher while my income does not, I would give serious consideration to renting out my spare bedroom to a coworker.

An excerpt from the daily meltdown (housing bubble blog):

Eventually though, all of those houses will be sold and occupied, it's just that the price will have to come down first. This might take a bankruptcy or two, but it will happen.

Peak Oil doesn't mean an end to energy. It's a gradual decline of cheap energy being replaced with more expensive energy. This will create imbalances in the market, which creative entrepenuers will capitalize on...

In any capitalistic society there is always a risk of recessions and depressions, but to see peak oil as a never ending great depression is a bit far fetched I think...

Good stuff. I agree with you on the FED's impotence. They won't be able to cause inflation if they wanted to. I read everything you wrote -- twice. Why is it that it's so easy to get people worked up about inflation, but any talk of the opposite goes in one ear and out the other? There probably aren't five people on this board who agree with your outlook. I know the feeling. Keep up the good work.

I haven't been posting because I've been busy -- not kidnapped. Hello, everyone.

Any reads on the current market? Not wanting to profit from it, just curious.

I remember when I was a kid, I had a math teacher who told me about how he and his sister never agreed on money. She saved everything, he spent everything. His reasoning? Spend it now, because it will be worth less in the future. I asked him if his sister was older than he was. He said she was. I told him that maybe her view was different because she could remember the Depression, and its deflation.

Despite the fact that he was much older and better educated than me (he was a college math instructor), he had never heard of deflation. He said there was no such thing. Finally, he went and got an economics teacher. She told him that yes, there was such a thing as inflation. He was astounded.

Just to make sure about what you are saying: under inflation, you spend it now; under deflation, you don't spend it because the money will be worth more later.

As the saying goes, In deflation, cash is king.

That is if we are on a turning point towards post-Peak Oil.

I have seen well built homes in the "wrong neighborhoods" suffer this fate in years past.

Alan

To date, the urban decay in America has tended to be from the inwards out: Detroit the canonical case. The City has just hollowed out-- there are open fields where once there were Victorian houses.

I don't deny the opposite is possible (think of any number of cases in other countries, for example, post oil booms), think some of those dying towns in Siberia.

What neighborhood is that? My impression is that suburban Detroit caught up with the 1920's buildout sometime in the 60's or 70's...

Basically I think the Ford Motor Company planned a new plant, and a new community to house its workers. When the Crash of 1929 came, the community was never built.

Big deal... not. We will simply see more baby boomers stay on the job a couple years longer and maybe help out at the grocery store.

Declining Energy production, a historic credit bubble and an aging working population points to the "perfect financial storm". All three seem to be converging in 2008.

Ever seen Koyaanisqatsi? http://www.koyaanisqatsi.org/films/koyaanisqatsi.php

Plenty of scenes of "empty housing developments as far as the eye can see" - admittedly mostly inner-city project-style buildings, but the point remains the same...

Take space away from the auto. Build housing on parking spaces (either new structures or expansions).

Best Hopes,

Alan

Issues like this are why the market cannot and will not provide an answer to this crisis in time except in one manner - discovery of a new energy source to continue the binge. Data like this demonstrate why this is "the long emergency" and needs to be addressed like an emergency, probably with emergency powers.

But we won't do it. We'll refuse and claim it is our right to be stupid. Thus and so shall die the automobile culture and with it much of what we know as the United States.

Yes, I agree. Adjusted for inflation & GNP, the writeoff of downtown commerical property (not counting residential) from 1950 to 1970 was of the same relative magnitude.

I think it can. I have lived in post-Katrina New Orleans and my view of what is possible and tolerable it much broader than yours.

Best Hopes,

Alan

As I said, I fear you are being too optimistic.

The City of New Orleans has had to pay for a search of dead bodies "missed" by FEMA contractors (see above). Over 100 dead found so far. We ran out of money just before last Christmas and no doubt some bodies were put into dumpsters as homes were demolished in the 2 months that followed. We started up the search again with the sales tax $ from Mardi Gras, but stopped again a month or so ago.

The Fire Dept. chief made the valid point that he had limited personnel and had to chose between the living and the dead. Fire protection is minimal (at best) and he pulled his men off the search. Off duty fire fighters continued the work as volunteers and found the 28th body since Mardi Gras last week,

There has been no "federal money spigot" for New Orleans, just the largely out of town contractors.

Best Hopes, but not for FEMA,

Alan

I came from Australia (space galore) to Hong Kong (space at an incredible premium). I have thrown away almost everything I own, and look forward to culling the rest.

I do not make these remarks as any criticism of Alan, but rather against anyone who says 'Can't be done'. People can certainly get used to much smaller spaces - especially when they have to.

One of my greatest fears - the hordes trying to escape the unsustainable cities will descend on the little burgs.

At first this might seem like a boon-time for the small towns and cites, but more than likely they will be likely be overwhelmed with city refugees and unable to cope with the extra burdens of delivering necessities to the refugee populations.

I imagine the city refugees will consist mostly of former middle managers with limited useful skills, and there families.

Then again, maybe these refugees will become good "migrant labor" for the smaller towns and the surrounding farmers whose fuel rations fail to meat their planting and harvesting needs ??

Coupla things. Several talked about this above - in my (early 90's) thesis, I took a look at the real vs. market cost of gasoline. We pay billions in health, environmental and defense costs associated with 'our oil' and 'our non-negotiable way of life' that does not get reflected at the pump, nor per mile driven, as it ought. Just leveling that playing filed would go a long way toward pushing us from the private car to the publci train.

But to me we've got to keep the bigger picture always in mind. Where are the people going to go? Suburbia can't go away? Well, a little ol' thing called carrying capacity may have a thing or two to say about that. We are deep in overshoot, and William Catton showed that 25 years ago. On the other side of peak, not only is our commute going to become more dear, but so is food production, and everything else that underpins our easy motoring lifestyle. We'll be plowing up yards to grow food, and yes, I expect there to be scavengers. Which is apt, as that's what we've become, detritivores living off the death of eons ago. It's so utterly unsustainable that to be arguing over gas tazxes and transit subsidies is absurd. The planet cannot sustain 8 or7 or 6 or ? billion of us, especially living as Americans feel entitled. Economize, localize, produce, as WT says. where will the people go? They will go hungry, then they will go away. You know where that is, right? It's where we throw our trash, where we offshore the unsightly aspects of our unsustainable lives, where we pump our pollution, where we turn our eyes away from. Away is coming our way, sooner than most would think.

The problem is working it as a fact-based conclusion. That is hard to do without combining those facts with assumptions of future behavior, future lifestyle, future technology. It would be interesting to see an overshoot argument made, while carefully noting the assumptions made along the way. IMO, there are are a lot of assumptions made in connecting those dots.

I don't feel like I'm being pinned down thought, because there isn't any secret underlying position. I really don't know.

And even then I could be wrong, and change my mind ;-)

Jim pointed out that by refusing to negotiate, we will have a new negotiating partner chosen for us--reality.

And IMO, that reality is coming hard and fast in the shape of the expectation of increasing US imports against the reality of declining world export capacity.

The only way for imports not to grow from their current level is if our consumption falls, barrel for barrel, at the same rate that our domestic production is declining. And this has to happen every single year going forward. But this is also true of all the new emerging importers, such as Indonesia and the UK. Some reports suggest that Iran could be a net importer in as little as 10 years. If everyone is on their way to becoming net importers, who is exporting?

I use it to reinforce the idea that we are looking for adaption today, in preparation for scarcity tomorrow.

Stuart's a smart guy, and I think he gets that above. He shows a lot of charts of current trends, but when he uses the words "[5-6% is] what Hubbert linearization suggests for eventual global decline rates" I think he's making careful use of the word "eventual."

Eventual as in when? If eventual is 20 years from now I think we have a lot of time for pre-adaption.

On the other hand, catastrophists would have us fear that eventual is next week, and the time for pre-adaption is past.

I haven't seen a good case to support that kind of deadline.

I assume that over that 20 years signals, and their associated responses, would build.

I don't assume steady-state until some fanciful cliff.

I always had this problem with Duncan's Olduvai Theory. The grids are going out in 2008! Worldwide!

Wait a minute... US, maybe... but worldwide? How do we get from US to 'worldwide'?

This is what I call the 'World Series Fallacy' - that the US is the entire world.

Just because the US (and, unfortunately, my native Australia) has a particular set of social, political and economic problems that means it will be hit very hard by Peak Oil, does not mean everyone else fares the same. The Third World will do even worse, Europe may do better ... provided they ditch you Americans and start cozying up to Russia, like smart people would in the circumstances.

Okay, I know this blog is US-centric. Still: keep it in mind. Death of US suburbia is not the end of Western society.

Europe may be more economical in some ways, but it is also crucially dependent on exports, and on imported energy (something like over 80% of our total energy use is imported).

Europe also has a hugely inflexible labour market and complete labour immobility. So any fall in aggregate demand feeds right through to unemployment, and hence to political stability. An Energy Crisis would hit Europe as hard as it would the US, even though we consume less oil per person.

If the US has a severe recession, Germany et al will follow. The US is 1/4th of the world's economy, and for the last 5 years at least, the US and China have accounted for something like 2/3rds world demand growth.

Under a business-as-usual scenario, when the US goes into recession, so do Germany, Japan, China and so on. If you think about it, it is ridiculous that the world can be organized in such a fashion.

'Doom' in the US means that these world 'business as usual' arrangements must be written off. The US would be on the mat and would not be getting up again, and this would be clearly visible to everyone who is left standing (and there will be, Peak Oil being more fundamental than the illusions of our 'globalized' i.e. US-weighted, economy). Those that have the physical capacity and resources would then cooperate amongst themselves.

I think Peak Oil takes down the US before it does Europe, and Europeans will adapt to what that means.

You write that you "think" "Peak Oil takes down the US before it does Europe, and Europeans will adapt to what that means. "

But it sounds like what you mean is you "hope" "Peak Oil takes down the US before it does Europe, and Europeans will adapt to what that means. "

That doesn't make it true and your utter lack of support for your ideas doesn't make them very convincing.

That's good enough for me as a first-order approximation.

But for you, it appears that mere mouth and projection serves as 'analysis'. It is you who 'hopes' and 'thinks', apparently, from your lack of argument.

Suit yourself.

The US is shrinking from the unsurpassed top dog, to one of the top dogs, in a much more interdependent world. China will be as big an economy as the US (sometime after 2040, perhaps 2050), and in aggregate the US will be a smaller portion of a (larger) pie.

Britain found this unbearably difficult, and went through economic and political crisis after crisis.

In the end, we invaded Suez in 1956 in collusion with Israel and France, and without American support.

Eisenhower thought this was an idiotic piece of colonialism, and refused to support the pound. Faced with a currency collapse, the British government had to withdraw in humiliation.

Could Iraq be America's Suez?

Well, as my Swedish gramma used to say, "Ufda!"

Right?

Amazingly, there is a lot more at the link.

We have a winner. The reaction of many to the contractions in spending will result in problems.

What do you think will be the reactions to a lack of spending on 'social programs' - as I expect they will be cut before the military is.

This view is the one which most logically leads to war - and Iraq and Sudan are merely the opening acts.

As others have noticed, every car advertisement shows you all alone in your beautiful shiny new car driving in some gorgeous location on this earth.

Until we stop painting car ownership and operation as though it is a club med type experience, people will keep doing it in the hopeless attempt to "get" that vacation experience in the car that they saw on the TV ad.

The fact is that people drive to get from point A to point B. In North America, save in a very few spots, that is best done by private car. If the driver actually enjoys the sensation of motoring, well and good. That's just a bonus. Many others dislike the stress but drive anyway. They have a destination to get to.

The advertising problem has to do with the size of the car, not the number of miles driven. Manufacturers are now advertising with people living in their cars... which is done to emphasize size and comfort, not basic road performance. The times when road performance mattered in ads is gone for ten years. Now it is all off-road performance (yeah, right... when did Mom take the Hummer into the mountains and drove all the way to the peak?) and size, capacity, towing etc..

We are being sold features and product performance we don't need. And too many people buy into that. They could be prevented from doing so... with a simple gas tax.

1.) It's much faster. As mentioned above, it takes at least twice as long to get just about anywhere, except into and out of the city during rush hour, when we're all in a world of hurt (cars still have a slight advantage, though).

2.) It's much more convenient. You don't have to wait on a bus platform or a wind-swept winter street for 20 minutes waiting for the damned thing to finally show up, you just get in your car and go. This is tied in with number 1 above. Also, you can go to the grocery store whenever you like and haul away as much as you want without having to worry about personally carrying it all back home for 45 minutes.

3.) It's much more dignified. Let me tell you, I think this one might have more to do with it than 1 and 2 put together. All other things being equal, would you rather sit in relative comfort in your own little heated/air conditioned space that's at your beck and call, or would you rather run your ass off to jump aboard an overcrowded train/bus, to be packed cheek by jowl with all manner of people (both savory and unsavory) while the conveyance lurches back and froth, tossing you into each other? Yeah, I thought so.

These three factors will combine, I believe, to make it so that cars will trump mass transit even when it is available until the last possible moment, if that moment does arrive.

So, thinking about all that, I advocate the auto club, where your cell phone connects you to any kind of transport you want- limo, junker, big van, garbage truck-- at the push of a button, which connects you to that educated computer which knows your preferences and sends the right thing to fit your needs and your pocket just right, and fast.

My student simulated this concept for our small town and it worked fine, saving huge amounts on money, parking, time wasted and the rest.

Some places have tried this in a sort of half-way, but not to the full degree that will capture the real value.

Owning a car is a stupid and inefficient way, relatively speaking, to get what we want. Why not own a bunch of them, and in the process forget about parking, upkeep and all the rest?

I have no patience at all with the pathetic creature who thinks owning a fancy car somehow makes him anything more than the jerk he is.

BTW, I enjoyed riding buses in LA, wherein I was almost always the only Anglo, treated with great friendliness by all the peasants, even tho I could only understand a fraction of their conversation. It was also fun to note that there seemed to be an unmentioned agreement with the driver that they didn't actually pay for their ride.

Also loved the tiny cars of Paris, especially the Smart Car.

You walk a lot more in Paris, but it's like walking through a giant art gallery. And the sidewalk cafes are simply great.

Because of the walking, I suppose, we simply didn't see any fat Parisians.

Even with all the wonderful food they eat.

Paris makes sense to me.

Our food is better than the excellent food of Paris, our architecture is different, we have LOTS of SUVs & pickups with Texas plates now, but hopefully gone by then.

Come visit :-)

Alan

"Duallies", Hummers, Espalanades, etc. were extremely rare pre-Katrina, and now common (most with Texas plates).

Oversized SUVs & PUs blasting down the street, faster than the 25 mph speed limit (locals drive 15-20 mph usually due to parked cars, people walking, etc.) are now common. More often than not with Texas plates.

Had one Aggie (gig em on bumper, Texas plates), turned wrong way on one way, backed up, cracked my light, and then refuse to stop as I blew my horn for about a mile. He ran red light to get away from me.

We welcome walking Texans :-)

Alan

And it is seldom minus 5 degrees and snowy in winter (again see US cities).

There's no way to easily reconfigure US cities to look like European ones. And indeed European cities are sprawling: people are moving out of the centre of Paris, and Madrid is sprouting new suburbs by the day. I always notice with my French friends that they all have cars, and many drive in Paris itself (in London, this is something I avoid if possible).

German cities are probably, on average, the best planned and nicest in Europe (we destroyed almost all of them in 1944-45, and they rebuilt them quite sensibly). Nonetheless Germans drive a lot and have a a lot of cars and suburbs, and drive at 100mph+ on the motorways.

Sure Europeans drive "a lot" but Euro vehicles get 40% higher mpg and travel 30% less VMT per vehicle (see http://www.martecgroup.com/cafe/CAFEmar02.pdf),plus there are many fewer vehicles per capita.

When I visit my wife's French relatives I am always amazed at the number of people who choose to sit in gridlocked Paris streets in their mini-cars while pedestrians pass them by, but those chosing to clog the streets are a very visible minority, while the vast majority uses feet, metro, and buses (in that order).

The migration to the 'exurbs' and 'ruburbs' is as great or a greater factor.

Even in a city like Toronto, where the construction of downtown is palpable (a micro city of 25,000 people being built along the lake, in the old railway lands)and where public transport is extensive, what is striking is the degree of sprawl into the Greater Toronto Area (60 miles by 60 miles) that is taking place, rather than a 5% increase in the population downtown.

Agree I haven't travelled widely in the US outside the coasts, the last 10 years.

When the people moved to the suburbs, but commuted downtown, then mass transit worked well. But now cities are configured around 'edge cities', big box stores and 'here there and everywhere' commuting (suburb to suburb, exurb to exurb, rural to suburban, urban back out into the suburbs). People shop, live and work in the extended megalopolis, rather than radially between suburb and downtown.

The effect is rather Los Angeles like. LA is a relatively dense city by US standards (who knew?-- it's one of those truly odd statistics) but population and work sprawl in every direction.

There are different ways of playing this: Denver investing in mass transit, v. Phoenix or Dallas Ft . Worth which are more sceptical of that approach, but the sprawl continues.

My conclusion is that more fuel efficient cars, smarter traffic management, are the more likely response rather than a recentralisation of American life.

http://www.valleymetro.org/METRO_light_rail/

Clearly all these cities continue to sprawl, but like almost all US cities are also investing in rail infrastructure as they go.

I like our Subaru, but I'm glad I don't have to drive every day. The luxury of traffic lights, congestion, regular maintenance and eventual breakdowns anyway is enough to remind me that the enjoyment of cars is costly, and often not convenient through and through..

Sociobiology applied to public transport?

Best Hopes,

Alan

Best Hopes for New Orleans,

Alan

1 and 2 are objective, can actually be measured, and are clearly related to the level of public transit in one's locale. Frequency of service is everything.

Factor Three is of a very subjective nature. It is a question of social conditioning. And what you call "dignity", Adam, would call "snobbery". As I say, it is very subjective.