Tech Talk - Conditions and Treatments in North Ghawar

Posted by Heading Out on May 27, 2012 - 6:14am

Recent Tech Talks have focused on the increased use of novel technology in Saudi Arabia as a means of recovering oil stranded during the waterfloods that have successfully sustained production over the past few decades. That technology is further expanded with the use of carbon dioxide injection as part of an Enhanced Oil Recovery program. The CO2 project has been in the works for some years, with an initial estimate that some 40 million cubic feet of CO2 would be injected daily into flooded areas of the Ghawar field. The gas will come from the Uthmaniyah Injection Plant and will be initially injected into seven wells in the Uthmaniyah section of Ghawar. The initial flood will be monitored, since it is important to ensure that the CO2 finds the oil that it will help flow to production wells.

Aramco has also recently announced success with changing the make-up of the injection water being pumped into the fields to sustain pressure. By altering the ionic composition and salinity of this water, it has been possible to significantly increase the amount of oil that is liberated and thus recovered from the reservoirs.

Ghawar is sufficiently large that it has been divided into different segments, and the conditions vary between them. Because of the differences between the various regions, the overall statement that Ghawar is producing some 5 mbd has to be read with a degree of caution, lest it be presumed that this has continued to be from the same regions of the overall field. (And while this article deals with oil production, it should be noted that Ghawar also produces around 2.5 billion cubic feet (bcf) of natural gas a day.)

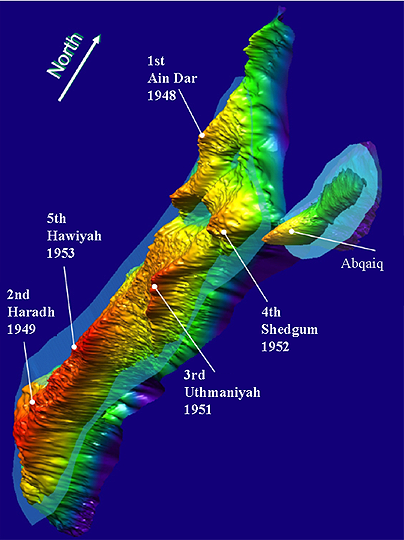

Ain Dar came on line in 1951 with an initial yield of 15.6 kbd of dry oil, and the field was given the overall name of Ghawar, from the Bedouin name of the overlying pasture, in 1952. The original well was still producing 2,100 bd of oil in 2008, having by then produced a total of 152 million barrels. Down at the other end of the field, the first Haradh well was put into production in 1964, and though mothballed for a while due to lack of demand, was still also producing in 2008, at a rate of 2,300 bd – for a total production of 24 million barrels. Shedgum 1 was brought onstream in 1954, and was sidetracked with a horizontal section in 2008, which brought production back to 3,700 bd. The first Hawiyah well went onstream in 1966, and by 2008 was still producing at 4,600 bd – having by that time produced some 51 million barrels of oil.

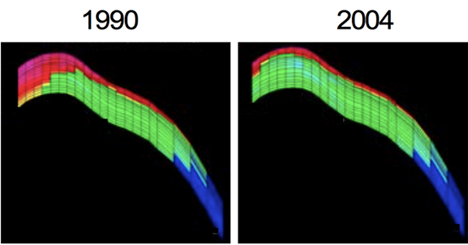

Stuart Staniford and Euan Mearns have, among others at The Oil Drum, provided extensive sets of information on Ghawar over the years. For those who are not familiar with the region, Stuart’s early description is a good place to start. In this brief overview, I will not get into any of the details of those descriptions, though I will quote one or two of the most relevant highlights. The debate initially focused on the amount of the waterflood in different regions of the field, since it was possible, with extensive work, to extract information on the rate that the water was advancing, relative to the remaining volumes in the different regions. For example, in one of his earlier posts, Stuart showed the following sequence of profiles for the water progression across a section of the field at Uthmaniyah. This was followed by an additional response from Euan.

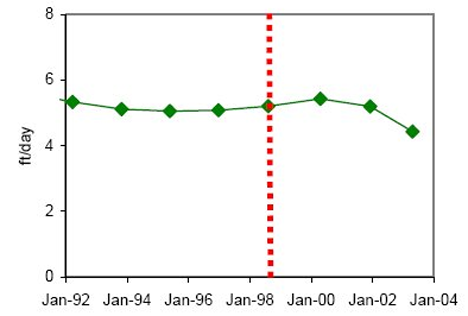

Stuart then continued this analysis into evaluating the conditions in North Ghawar (i.e. Shedgum and Ain Dar) leading him, based on figures such as this:

This led him to accept a prediction from Fractional Flow, who had earlier noted that production in Northern Ghawar had fallen (in 2007) from the 2mbd oil and 1 mbd water of 2003 to 300 kbd oil and 2.7 mbd water in 2007, as follows:

*90% or so of 'Ain Dar/Shedgum's 2mbpd could water out over the course of a few years.

*We are likely somewhere in the midst of that process.

*That is likely the explanation for most of the Saudi production declines we have seen since June 2005 (including the failure of Haradh III and Qatif/Abu Safah to raise production).

The discussion at the time (which is still present in comments under the main papers) was fascinating, since it was based, inter alia, on information such as the speed at which the water front was advancing.

The use of horizontal wells and MRC came late in the development of North Ghawar, which is why the use of carbon dioxide injection for EOR, smartwater injection, induced fractures, and long horizontal wells to capture otherwise stranded oil, will play a more important part in the production from the region.

What these new technologies bring with them is the ability to go back into the older regions of Ghawar and extract some of the oil that was left in place during the original water floods. Because a number of them will be dealing with regions of the reservoir that are already flooded, so that the oil will be coming from wells with a high water cut, it is, in my opinion, unlikely that these will allow increases in production from the region, but rather it will sustain existing production levels somewhat further into the future than we (the collective wisdom of the TOD writers) have predicted in the past.

But Ghawar is not just the original wells of the North, and I will have more to say about the field, and then about other fields in the country, in future posts.

Perhaps jumping ahead, but Haradh has tighter rock (lower darcies) and lower quality oil (lower API) than the rest of Ghawar.

Thus Haradh, per my limited understanding, had minimal exploitation until three 300,000 b/day projects were implemented in quick succession around 2000. It can likely produce at that rate for a half century or longer. However, the temptation to increase that rate of extraction will be strong in the coming years.

Are there any signs that Aramco has succumbed to that temptation and increased teh production rate at Haradh ?

Thanks,

Alan

Alan:

JoulesBurn has been looking at the Haradh developments for some time, see for example, here and would be better able to comment.

"Thus Haradh, per my limited understanding, had minimal exploitation until three 300,000 b/day projects were implemented in quick succession around 2000. It can likely produce at that rate for a half century or longer."

I can vaguely remember thirty years from somewhere but can not find it now. I would expect Haradh to decline last since it is the least good area and it was developed last or put another way then Haradh decline Ghawar would be almost empty. Even if it is almost empty there would however be some more to get by scraping the bottom.

The Haradh section of Ghawar does have much tighter rock than that found in the North Ghawar - with Haradh's Permeability=52 mllidarcies, versus 617 millidarcies for Ain Dar and 639 millidarcies for Shedgum.

While the porosity at Haradh is not especially low, it is somewhat lower at 14% than is found in Ain Dar and Shedgum, which are both at 19% porosity. Decent porosity with low permeability would seem to suggest a potential candidate for fracking. I don't really know if the modern, aggressive, hydro-fracking style now seen in the USA is currently used, or planned for use, at Ghawar - but this might be a very interesting approach to see applied to the world's greatest oil field (assuming that the Saudis allow us to "see" much in the way of specific results..?).

However, I don't completely agree with the "lower API" part of the quoted comment. I have read that the oil quality of Haradh is only slightly lower than oil in the rest of Ghawar. At http://www.gregcroft.com/ghawar.ivnu Haradh is shown as having Oil Gravity of 32 degrees API (another source says 33 degrees API for Haradh) while both Ain Dar and Shedgum are listed with Oil Gravity=34 degrees API. 32 and 34 degrees API (although near the lower end) are both within the established range for Arab Light oil, which is the oil grade found throughout all sections of Gharwar and other Saudi onshore fields as well. While Arab medium and heavy oil grades are typically produced from the Saudi offshore fields in the Persian Gulf, like Safaniyah and Manifa.

Heading out, I read your comments and links with great interest. Not much I can comment on because you covered it all. Please don't conclude from the lack of comments that your input is not appreciated. It definitely is.

Oh, I read this morning that Abu Dhabi May Inject CO2 in Offshore Fields to Boost Output just as Saudi Arabia is doing in Ghawar. I believe this is a sure sign of fast decline and desperate efforts to try to slow that decline.

Ron Patterson

I am not so sure that it is a "sure sign of fast decline".

The Emirates have the most conservative extraction policy in the world (from memory, 100 years to depletion - since ramped up).

Perhaps good petroleum engineering has suggested this as a way to extend reserves, without the immediate pressure of depletion. These are hereditary monarchies - leave some oil for the son.

As Rockman has pointed out, starting enhanced recovery early is better than later.

Even in North Ghawar, "watering out" is a process that will take, at a minimum, the better part of a decade or a bit more time. I do think that we are well into that "better part of a decade", but there are a few years left (I Hope !) before all that is left is going after "attic oil", stranded oil and "oil stained water".

And those scraps will be significant in the first few years.

Alan

Well their old wells are definitely in fast decline just like those in North Ghawar. However, like Saudi, they have had a massive infill drilling program going for years now and have managed to keep production from falling. They are currently producing almost, but not quite, as much as they produced in the first half of 2008.

Ron P.

I second this. These articles are very informative, and help me out understanding stuff very well. I rarely comment (although I do sometimes) but that is because what is discussed here is far above my reach. I read, and learn.

Keep em comming.

Perhaps a comment on the article from Business Insider may be relevant:

http://www.businessinsider.com/barton-biggs-saudi-arabia-bankrupt-iraq-i...

I find these articles fascinating, particzularly as I used to drive the deserts of Saudi Arabia years ago in an old 4WD.

There was one kind of desert we didn't drive over and that was "Sabkhah". Discernible as flat regions with a dark surface, we knew that if you ever got stuck you might even lose your vehicle! So we avoided them at all costs.

imho you have to take some of the theories about Saudi with a bucket of salt. I heard one during the Deepwater crisis about a huge oil spill in the 1990s which the Saudis covered up. I spent a lot of time out on boats in the Gulf during that time and can say there was no such oil spill.

Keep sane.