Can an Economy Learn to Live with Increasingly High Oil Prices?

Posted by Gail the Actuary on October 11, 2012 - 4:10am

Prof. James Hamilton of University of California recently wrote a post called Thresholds in the economic effects of oil prices. In it, he concludes

As U.S. retail gasoline prices once again near $4.00 a gallon, does this pose a threat to the economy and President Obama’s prospects for re-election? My answer is no.

EDIT - I originally wrote this post thinking that Prof. Hamilton was looking at a broader question: Can an economy learn to live with increasingly high oil prices? After looking again at his article again, I realize that he is talking about a narrow question: Using the figures he was looking at (average gasoline prices across all grades), prices were for the week of Sept. 17 near $4 a gallon, as they had been several times in the past, as they bounced up and down.

In that context, what he says is far closer to right than what my analysis of the broader question of whether an economy can learn to live with increasingly high oil prices, below, would suggest. There is a difference, because gasoline prices are not too closely tied to oil prices in short term fluctuations, and because the issue is likely to be as much one of consumer sentiment as anything else, as long as the issue is simply one of gasoline prices in a not-too-wide range. But I think there are some longer-term, more general issues we should be concerned about.

My Analysis of the More General Question: Can an Economy Learn to Live with Increasingly High Oil Prices?

As I see it, increasingly high oil prices weaken an economy because they reduce discretionary spending and indirectly cause people to be laid-off from work. They have many other adverse effects as well–they tend to raise food prices, with similar effect. The laid-off workers require unemployment compensation payments, and the same time they are contributing less tax revenue. All of this creates a huge imbalance between revenue collected by governments and expenditures paid out. If oil prices rise again, it will tend to make the imbalance worse.

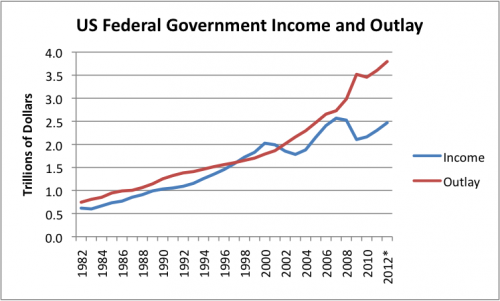

An economy such as the United States can cover up the problems caused by high oil prices with variety of financial techniques. In my view, high consumer confidence measures the success of those cover-ups, more than it measures the actual underlying situation. One way the US government has managed to cover up how badly the economy is being hurt by high oil prices is by spending far more than the government takes in as revenue. This has happened continuously since late 2008, with outgo exceeding income by more than 50% each year, even though the country is supposedly not in recession.

Figure 1. US Government Income and Outlay, based on historical tables from the White House Office of Management and Budget (Table 1.1). Amounts include off-budget spending, such as Social Security and Medicare, in addition to on-budget spending. *2012 is estimated. Office of Management and Budget/Historical Tables.

The amount consumers have available to spend on cars and gasoline is very much affected by deficit spending. With deficit spending, government employment can remain high and transfer payments can continue, without anyone really “paying” for these costs, putting more money into the economy to spend on oil and cars.

There are other government programs as well. Interest rates on homes and new cars are being kept at record lows, leaving consumers with more money to spend on cars and gasoline. Low interest rates and low taxes also stimulate employers to hire more employees. Quantitative easing helps contribute to higher stock market prices, and makes it easier for the federal government to keep adding large amount of debt.

To me, the fact that the economy is not currently completely “in the tank” speaks more to the success of stimulus programs than having anything to do with adaptation to higher price levels. Countries such as Greece, Spain and Italy do not have the luxury of being able to hide the impacts of their high cost of oil. They are doing less well financially, but were not included in Hamilton’s analysis.

Easy to Overestimate Impact of Recent Changes in Vehicles

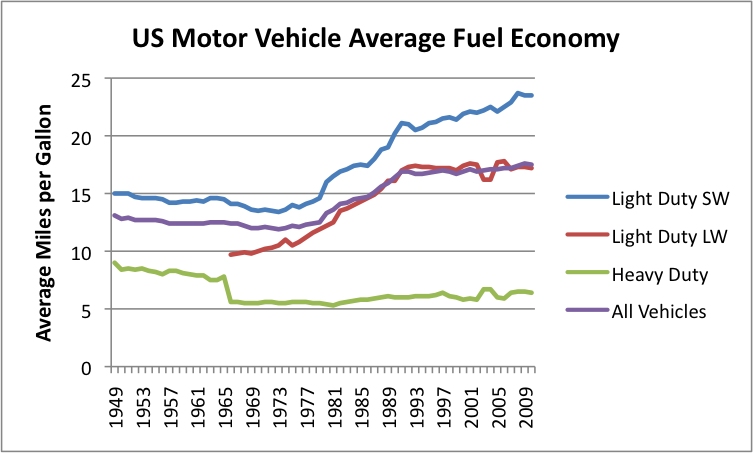

With vehicles, we are dealing with a mixture of vehicles of all ages. The average age of automobiles is now estimated to be 10.8 years. The average age of trucks is no doubt greater. The EIA provides a summary of average fuel economy by type of vehicle based on US Federal Highway Administration Data, summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2. US Motor Vehicle Average Fuel Economy based on US Federal Highway Administration Data (Based on EIA Annual Energy Review, Table 2.8) SW = Short Wheelbase; LW = Long Wheelbase.

This data is only through 2010. While it shows some improvement in efficiency of light duty short wheelbase vehicles, it shows little improvement in efficiency overall. The big increases in efficiency were in the period between 1973 and 1991.

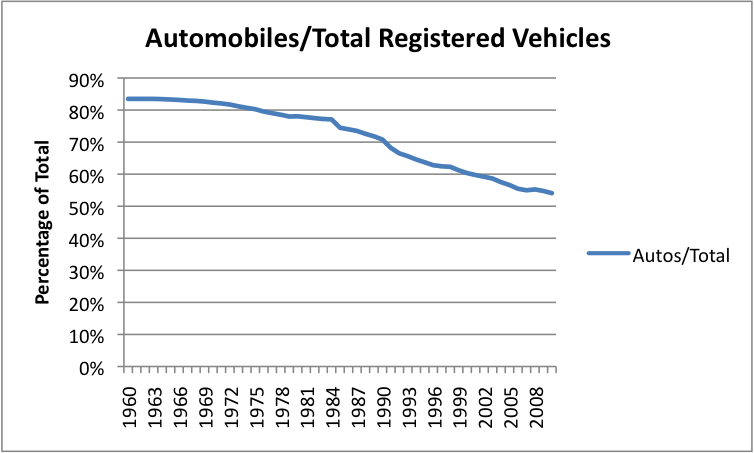

The mix of cars by type is concerning.

Figure 3. Automobiles as percentage of total registered vehicles, based on data of the Federal Highway Administration.

The percentage of automobiles has been dropping, as the number of SUV and trucks has been rising. The change between 2008 and 2010 reflects the fact that the number of “automobile” registrations dropped by 4.5% in that time-period, while the number of other (larger) vehicles rose slightly. Thus, the long-term trend to relatively more of the larger vehicles continued. Obviously, this data doesn’t show carpooling and other adaptations, but it is difficult to see any recent big trend toward efficiency.

Can the Economy Weather another Rise to $4.00 Gasoline?

The question of whether the economy can weather $4.00 gasoline, to me, depends on the issue of whether the US government can keep coming up with more manipulations to hide its financial problems.

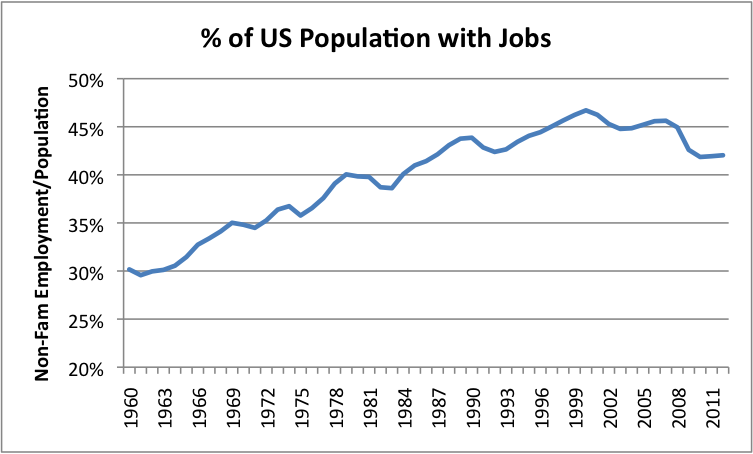

The US economy started to run into severe headwinds about the year 2001. This is when the percentage of Americans with jobs started falling.

Figure 4. US Number Employed / Population, where US Number Employed is Total Non-Farm Workers from Current Employment Statistics of the Bureau of Labor Statistics and Population is US Resident Population from the US Census. (This includes children and others not usually in the labor force.) 2012 is a partial year estimate.

While economists don’t seem to attribute past economic growth to increasing employment percentages, it seems logical to believe they played a role in the long-term growth in the 1960 to 2000 period. The economic growth came not just from the work these employees did themselves, but from the fossil fuels they used on the job. The wages the employees obtained for doing the work allowed the workers to buy products others had made. The long-term growth in non-farm employment between 1960 and 2000 was enabled by increased productivity in the agricultural sector, which was also fueled by increasing use of fossil fuels.

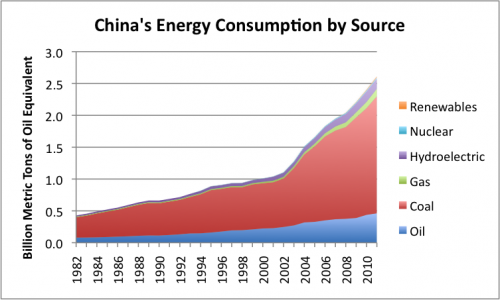

The percentage of the US population with jobs started falling starting in 2001. This is very close to the time when the US started importing far more goods from China, India, and the rest of Asia. If we look at energy consumption for China, we see a sharp increase in energy consumption about 2002:

Figure 5. China’s energy consumption by source, based on BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy data.

We can also look at broader groupings of energy consumption, and see a similar pattern:

Figure 6. Energy Consumption Divided among three parts of the world: (1) The combination of the European Union-27, USA, and Japan, (2) The Former Soviet Union, and (3) The Rest of the World, based on data from BP’s 2012 Statistical Review of World Energy.

The cost of goods produced in Asia is cheaper for two reasons:

(1) They tend to use a lot of coal in their energy mix, keeping energy costs down.

(2) Wages are far lower. One reason wages can be lower is because of the warmer climate.

It seems to be an article of faith of economists today that the US economy and the European economies will return to growth. Then the stimulus can be removed, and everyone can live happily ever after. But is this really something we should be expecting? We really have two kinds of headwinds: (1) higher oil prices, and (2) cheaper competition for jobs from Asia and other developing countries.

As far back as 2001, we read about Greenspan stimulating the economy by lowering interest rates. Various other approaches were used as well, including encouraging more home ownership through subprime loans in the 2002 to 2006 period. The greater demand for homes helped create jobs in the construction industry and helped raise home prices. By refinancing their homes, consumers were able to have funds for purchases they could not otherwise afford. In recent years, we have added a whole list of new stimulus approaches.

I would ask: Aren’t we kidding ourselves if we think a small increase in miles per gallons on new cars is going to fix the problem of another upward bounce in oil prices? Aren’t there some much more basic issues “out there” that need to be fixed as well? Aren’t we fighting two kinds of downside risks to the economy with increasing stimulus, and only marginal success? If oil prices rise some more, aren’t we likely to need “more stimulus”? Where would it possibly come from?

Originally posted at Our Finite World.

You seem to be ignoring the obvious answer, which is "YES" because those in Europe have had much higher prices for decades. Their economic problems have been caused by unmet financial fraud and bailing out banks that got caught in the US-initiated credit crunch. They haven't really been causal connected to energy - but to lack of financial regulation.

It takes adaptation time however. You can't ask a 300lbs man to run a marathon tomorrow, but if you train him over a period of years, then it's certainly possible.

The real question is: "Can the World Economy Learn to Live with Increasingly High Oil Prices? Oil prices are rising all over the world, not just in the USA. Europe is having much harder problems with high oil prices than the US seems to be having.

You could not be more wrong. World economic problems are directly related to the high price of oil. And economists all over the world are sounding the alarm.

Will high oil costs permanently ruin world’s economy?

And here is a great Article just recently published in Forbes:

The Price Of Oil Is The New Economic Spoiler

The charts here are great and they do prove that high oil prices cause recessions. But they in no way prove that QE1 and QE2 caused those high oil prices. However...

Simply because European nations have higher gasoline prices than the USA proves nothing. Europe is geared to smaller cars and mass transportation. High oil prices affect the US transportation industry dramatically because our whole transportation system is geared to cheap energy, just like the rest of our economy.

And the very obvious answer to Gail's question is NO the economy cannot learn to live with increasingly high oil prices.

Ron P.

Darwinian wrote: "Simply because European nations have higher gasoline prices than the USA proves nothing. Europe is geared to smaller cars and mass transportation."

We have smaller cars and mass transportation BECAUSE European nations have had higher gasoline prices than the USA for decades.

With high taxation of oil products the increase of crude prices do not affect the European consumer as much as their US counterpart, despite low gasoline prices J6P pays more of his income for commuting than his European counterpart and gets skrewed much more by price hikes.

The ratio of GDP/per barrel is in many European countries, even those with high industrial production much higher than in the USA.

Therfore, without the finacial crisis my bet would be that European countris can cope much better with higher oil prices, however, with the current EURO crisis the playing field is much more leveled.

That statement implies that high oil prices had little or nothing to do with the financial crisis. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Did High Oil Prices cause the Financial Crash?

This is just one of hundreds of articles on-line that explains that the high price of oil, if not the sole cause of the great recession, was most definitely the major cause.

And one thing you, and others, seem to forget. The price of oil affects the price of everything not just the price of gasoline. Food prices are higher, it cost more to ship everything, it cost more to manufacture everything, everything is higher. Other than the price of petrol, European nations was just as affected by the high price of oil as the USA.

Ron P.

The "financial crisis" is more or less a debt crisis and it started a long time ago : basically further to the dropping of Bretton Woods (wich happens to be right after US production peak)

As to who is doing better between the US and Europe, maybe we shouldn't also forget that :

1) the US is still the third oil producer in the world (and much higher than North Sea production)

2) the $ is still the reserve currency

Otherwise yes also think that what is today called "the financial ccrisis" is primarily an oil crisis (the peakoil oil shock), rendered even worse with the mountains of debts (or accelerated by the corresponding credit since many years).

Yes, but you should also not forget: :-)

1) The USA per capita consumption is twice as high as the European, even with 45% domestic production, the absolut import dependency (barrel/capita) is still larger, sorry.

2) You produce per barrel only 60% of what modern European economies get out of a barrel.

3) You substitute expensive imports with expensive domestic production, good for trade balance, but still not good if you compete with other economies on the global export market (see 2).

4) I do not see despite (1-3) that improving the US energy efficiency has a high priority in the political agenda of your presidental candidates, good luck with that. :-)

Yes fully agree with you :-)

(wrote about the same a bit below regarding what would be US oil import dependency with similar efficiency per capita as in Europe considering current US domestic prod)

But by the way I'm French, understand you're German ? :)

And clearly the fact that taxes is such a taboo in the US doesn't help, especially as I see volume based taxes on fossile fuels as very different from percentages sales taxes or taxes on work for instance, it really is a political decision on accelerating adpatation more than anything else.

I am a German from Lower Saxony in Austrian exile since 1997. However, with two perfectly Austrian kids - this s*** happened even with two German parents- my Germanness is now really in doubt, so maybe I should use in future the label "European inside" instead. :-)

Your points 1-3 are probably right, although I cannot confirm. With respect to #4, Obama has put in place light duty and heavy duty fuel economy standards. The result of those standards is that light cars and trucks need to average improved fuel economy each year until the year 2025 when those vehicles need to average 54 miles per gallon. I understand that Romney has pledged to roll back those standards.

It is strange that both discuss energy supply, not fuel or energy efficiency. I guess that Obama fears that Romney will label him as an over-regulator of the business community thus killing jobs.

All these assumptions expect that in 2025 everything will be fundamentally the same as now.

I see the present as the top of a helter-skelter of shortage on all fronts which will make all predictions meaningless.

@Retsel,

Nothing "strange" about it.

In the USofA, "energy efficiency" is a socialist code term. A lot like "gobal warming", "overpopulation", or "Peak Oil". All liberal myths created by pot smoking hippies and greedy scientists to scare us "real" Uhmerikans and trick us into into accepting their socialist One World government agenda. Not surprising such a plan came from our Indonesian socialist "President".

Over here, energy waste is a source of national PRIDE. the smoke belching out of the tail pipe of my Hummer is just the SMELL OF FREEDOM, baby! Hell, we're creating jobs just by driving around. U-S-A, U-S-A, U-S-A!!

(sorry, been watching too much Fox News lately...)

I don't see many Hummers around anymore. They sold about 152,000 H2s and 159,000 H3s according to Wiki. Most of them must be in somebody's barn waiting for the collector value to go up.

I see them fairly often , around various points in S. Cali, usually in or near beach cities.

K.

But the consistently rising energy and commodity prices were what finally broke the back of exponential growth. There has been a sort of frenzied tarantella of expansion, with surging oil production locked into consumer and industrial growth. The oil dance is now over and somebody is being eaten.

You've heard the phrase "the straw that broke the camel's back"?

Do you pick on that last straw as the cause of the camel's demise, or rather is it the other hundredweight of straw that you put on before?

Oil price rises were a widely spread, globally connected stressor on the global economy - true. But those prices were bearable, except for the other things going on.

In particular, the GFC's cause can be laid at widespread endemic fraud in the global financial marketplace, the concious design of it such that it was uncontrollable (and thus money could be made), and the failure of governments to regulate it such that it was a rational system. That's the hundredweight of straw.

Now, westernised economies CAN deal with higher oil prices (Europe shows that), if given the adaptation time. Whilst I'll accept Gail's point that tax goes back into the general economy, you can hardly say that Europe is lightly taxed elsewhere as a result! Decisions of government spend levels makes even that 60% tax level moot.

The point however, is that looking at simple prices and saying "at what level will things break" is the wrong way to look at it. Instead you need to look at price as a rationing mechanism - driving out certain usages in certain locations, in order to balance demand to the available supply. The price will rise to the level needed to do that.

So the real question is, at what level of chaotic, price mediated, rationing of fuel will the wheels start to come off the connected systems of our society?

Posed this way, things become more obvious and simple.

Our rationing, and our method of rationing are not rational. Not only is the fuel resource not apportioned relative to the need to keep the systems of society working, the rationing mechanism acts to syphon that imaginary thing called money away from those that need to use it to change, towards those who are likely to waste it (in societal terms).

What we have is poor rationing mechanism.

Now, taking that into account, we can assume that as rationing continues, the unconsidered necessities of the societal system will mean that progressively more and more key value chains will break. Although it would be nice to think that SUVs will rust in the garage due to high fuel bills; the reality is that the poor developing world farmer will be unable to get his crop to market first.

The reality is oil prices are just one possible straw. The camel still has the hundredweight of financial fraud on it's back, the straw is still being added in a variety of forms - and the splint we put across it's back is not that strong and is already bowed dangerously.

We COULD fix the rationing mechanism, which COULD buy us the time to adapt, somewhat. But we aren't and won't.

There's little doubt that oil prices peaking in the summer of 2008 helped to push the economy over the edge, but oil prices by themselves cannot totally explain the global housing bubble or exploding consumer debt levels from the early 00's on. It's silly to ignore the role of the Federal Reserve and ZIRP (zero interest rate policy), the explosion of MBSs and other derivatives, the late 1990's tech stock bubble (the bursting of which the Fed claims it was trying to mitigate), or the raft of financial deregulation that started with Reagan, and climaxed under Clinton and Bush II (pun intended).

The global housing and consumer debt bubble, largely caused Fed's ZIRP + Commodity Futures Modernization Act (2000) + Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (repealed Glass-Steagall 1999), and the resulting explosion in MBSs and CDOs had *at least* as much to do with the so-called financial "crisis" of 2008 as the price of oil did. High oil prices were just the straw that broke the camel's back.

Sometimes here at TOD it's too easy to get tunnel-visioned about oil/energy and forget that some large-scale economic events may have other root causes.

Totally agree. One other thing, all those fraudulent financial trends you identified were done to keep the system going a bit longer. If ZIRP, QE, etc. hadn't been instituted then the financial system would have collapsed well over a decade ago. In fact, these manipulations have been going on for a loonngg time. Suppression of gold and silver has been going on for well over half a century now. Suppression of oil prices is now firmly entrenched. Suppression of gold, silver, and oil is the same thing as inflating US dollars, which is what the center of the world's financial system revolves around. This is simply the modern version of what an empire does to keep itself going. It's no different than the Roman Empire or any of the other empires you learned about in history. We are servants serving that empire. The US dollar is the center of that. The trade deficit enables goods to enter the US and dollars to leave. The US military is what keeps that flow happening, by forcing countries to accept dollars in return for their trade surpluses. As all empires invariably overxtend themselves and collapse, this is what we are now witnessing. 70% of US government debt now comes from the Fed printing the money into thin air -- it's monetized. The rest of the world doesn't have enough trade surplus to fund US debt anymore.

The brainless economists think that the world can continue to resume growth once the "recovery" happens, and then interest rates can return into positive real territory and then they can continue pummelling gold and silver and oil. Of course, growth will not continue and their plans will not materialize.

Now, when the financial system collapses it will be catastrophic. And China is busy accumulating the gold which used to be at Ft. Knox, which has been sold at firesale prices over the last decade by the criminals leading the US financial system as they try to suppress the market and prop up the dollar. When the financial system finally collapses only gold and other hard assets will remain as stores of wealth, and China will likely have most of it. Then China may emerge as the new economic superpower for a while, since they will then likely have the new reserve currency since they have the gold. Of course they don't have the resources, which makes this a bit different than the path the US enjoyed, but they may be able to fake that for a while using trade deficits. But on the other hand, since the world is rapidly running out of oil, this centralized control by empires may not materialize to the extent that the US has forced itself upon the world. Militaries can't "police" the word if they don't have the energy to do it.

"When the financial system finally collapses only gold and other hard assets will remain as stores of wealth..."

Just a small point to make here...but just as one cannot eat paper dollars, one cannot eat or heat one's home with gold. Why it continues to captivate people's imagination is beyond me.

"Then China may emerge as the new economic superpower for a while...they don't have the resources, which makes this a bit different than the path the US enjoyed..."

I give China a bit more credit than that - they must have studied the way the US has manipulated the world for the past century. The US doesn't really have the resources either, but we've manipulated the rest of the world into giving them to us at fire-sale prices. The big problem is that China could take everything the US has...and it would bring their citizens 27% of what it does in the US. 1,300 million people vs. 350 million.

To get what the United states has, China has to "eat the lunch" of the United States (350 million), Canada (35m) ,U.K. (62m), Germany (82m), France (65m), Australia (23m), Sweden (10m), Denmark (6m), Norway (5m), Switzerland (8m), New Zealand (5)... and that's only 651 million - HALF.

And then there's India...!

But going from a lean-to to a small house with running water represents a much greater quality of life jump and lower energy transition than going from a 3,000 square foot house to 6,000 sq.ft. and increasing your SUV count. But China and India have been sold the image of Beverly Hills. Gangnam style or bust.

The world requires a medium of exchange. While you can't eat gold, you do eat food, and until everyone goes back to the farm and grows their own food (impossible) then you have to pay for it using something. At the level of sophistication we have achieved, the world cannot function on a barter system. If and when at some point paper can no longer hold value then what are the alternatives as a medium of exchange and store of value? When you think about it there are very few, and precious metals are basically the only things. Therefore, currencies will eventually be backed by PM's and possibly also commodities, although PM's are easier to institute. The amount of physical PM's available is tiny in comparison to the amount of perceived wealth out there, and the central banks have levered he PM markets 100:1 paper:actual metal. When the transition happens it will be an elephant going through a wormhole.

Who is going to issue the new currency backed by precious metals? If some entity starts to issue paper currency backed by a precious metal, are you going to trade your cache of precious metal for that paper currency? And at what discount? (And, if you have not been prudent enough to take physical possession of your precious metal before things get bad, you probably will not get anything for it.) If civilization has deteriorated to the point that existing paper currencies are no longer accepted, it will take time to establish a new system. Survivors may well have to rely on barter for a while. So, how much of a krugerrand would you trade for a dozen eggs?

The survivalists in the US seem to be banking on pre-1965 US silver coins. They are easily recognized, 90% silver and hard to counterfeit.

If (when) the fiat money system falls apart, I don't think it will take long for people to settle on how many silver cents a dozen eggs is. The gold coins and ounce silver bars will see use for large purchases.

"The survivalists in the US seem to be banking on pre-1965 US silver coins."

In principle it would work. The 'yabut' is that there are not enough of them. How many units of currency would you need to keep even a crashed economy working at all?

And if you say deflation will make a silver dime worth $10 fiat, now I need to subdivide the dime. Stuck there too.

"How many units of currency would you need to keep even a crashed economy working at all?"

That may depend on how many survivors there are to circulate the coins. And on how easily you can get people to agree on what they are worth. I suspect that until a currency becomes legal tender for taxes and debts, every transaction will involve haggling and a lot of bartering will continue.

I think some time around 2015-2017 our current financial system will collapse. At that point we will probably get a massive dollar devaluation that will restore confidence back in the (now diluted) paper currencies. To get some indication of the future price of gold, divide the external liabilities of the US with the gold reserves of the US. Today the number is around $11,000/oz (it was around $800/oz in 1980). The Fed could announce that they will buy all available gold at $11,000/oz. Paying massive debt with devalued dollars, euros, and rupees is not a big deal. Ofcourse this will impoverish people without hard assets. Why people with savings are not buying hard assets today is beyond my understanding.

Bottom line is that you will always pay with dollars, not krugerrands, for a dozen eggs. However, you will pay a lot more dollars in the future compared to today.

There's another reason for that. Europe has historically had very little oil of its own outside of the recent North Sea / Norwegian finds. Had Europe been like the United States with a Texas-like source of oil to begin with, it'd have been a lot different - more like the United States. It isn't because of higher prices therefore, necessarily, it's because the Europeans had never a chance otherwise.

There will be much suffering as the Russian and Eastern Bloc sources begin with withdraw their veins that feed the over-dependent Europeans. In contrast, the United States could persevere (physically, but not economically) with its own oil production, perhaps with some purloined Canadian too.

OK, there we have an issue. The decision to highly tax oil products is a purly political one, a problem many US citizens do not get :-)!

You have in Norway (exporter) a very high taxation and you may find countries without a domestic production with relatively low taxation, it is simply an approach to curb the consumption of strategically important stuff that is imported or may deplete at home in near future, so the USA may simply lagg behind since 1971. :-)

With the political will the US could, just as from 1942-1954, cut oil usage by 20% and STILL

maintain transit mobility by simply running existing Green public transit and ceasing to subsidize Auto Addiction. As I have pointed out before the US actually has more Green public transit available than most people realize. Brookings 2 year study of Census data, jobs and transit stops found in May, 2011 that in 100 US Metro areas without laying a single Rail that 70% of working age Americans lived only 3/4ths mile from a Transit stop!

http://www.brookings.edu/research/reports/2011/05/12-jobs-and-transit

The problem is that given the horrible frequency of Green public transit, lack of local/express service, poor connections and lack of the last mile only 30% could reach a job on Green Transit in less than 90 minutes. This is easy and cheap to fix - simply restore all the Transit cuts in 150 cities since 2008 to begin with. Then run all trains every 20-30 minutes 7 days per week. Add shuttles for the last mile, build very cheap bike paths. Then restore strategic parts of the US existing 233,000 miles of Rail to passenger service. Many of these tracks are already running periodic freight and periodic leaf peeper tourist trains and could run frequent passenger service. Finally begin building key Rail lines down Interstate Medians as they were designed to do like I87/287 in New York/ New Jersey which could connect 10 different running Rail lines.

From 1942-1945 intercity trains, buses, trolleys and commuter rail ridership quadrupled in just 3 years to deal with WW II. We could do the same right now.

I don't think it proves anything. There are a couple of important things to note:

1. The supposedly high oil prices really represent a tax that is charged on certain types of oil consumption in Europe. The fact that more is charged on oil means that less is charged on other goods. It is really the total that is relevant. This approach is intended to get people to buy smaller cars.

2. It is not clear that these taxes really save Europe from the impact of higher oil prices. There are a number of countries close to "in the tank" from high oil prices in Europe (The PIIGS: Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain). These have been countries with the highest proportion of imported oil in their energy mix.

From Why are high oil prices no affecting Europe more than the US?

The taxes affect some oil use, but not all. But when prices rise, there is still a problem with higher unemployment and rising government deficits in countries with high oil usage.

"1. The supposedly high oil prices really represent a tax that is charged on certain types of oil consumption in Europe. The fact that more is charged on oil means that less is charged on other goods. It is really the total that is relevant. This approach is intended to get people to buy smaller cars."

Yes for sure, at a country level the price is the same for everybody, but again : European countries have almost no oil besides UK and Norway (and a bit Italy), and never had any, so comparing with the US which is still the third producer, and was the first up to beginning 70ies (when exactly ?), first exporter up to the 50ies I think, is a bit difficult.

"U.S. fields accounted for slightly more than 70 percent of world oil production in 1925, around 63 percent in 1941, and over 50 percent in 1950."

http://www.americanforeignrelations.com/O-W/Oil-Oil-and-world-power.html

What should be compared is European countries as now and as if the volume based taxes had not been put. Obviously tough to do, but would bet the mess would be more serious (and for instance the cars or trains less competitive on export market).

For me the major difference between today and the seventies is that we are not even able anymore to name the problem (a gigantic oil shock), which can be understood if for most people, even if not saying it, the deal is done anyway (crash coming).

IMO, most oil importing OECD countries are pretty much in the same situation. So far at least, since 2005, we have been forced to make do with a declining share of a declining volume of Global Net Exports of oil (GNE*) as the developing countries, led by China, consumed an increasing share of a declining volume of GNE.

At the 2005 to 2011 rate of decline in the ratio of GNE to Chindia's Net Imports (CNI), the GNE/CNI ratio would approach 1.0 around the year 2030, 18 years from now, when China and India alone would theoretically consume 100% of GNE. While I don't think that will actually happen (and we have seen signs of slowing demand in the Chindia region), the fact remains that rate of decline in the GNE/CNI has accelerated in recent years, hitting an almost double digit rate from 2008 to 2011 (falling at 9.5%/year).

*Top 33 net oil exporters in 2005, BP + Minor EIA data

To me provided every country pays the same price on the market (which might not be the case in the future through specific bilateral contracts already being set up) the ratio of consumption between China+India and OECD doesn't appear as a major parameter. More important is to decrease oil dependency (or oil per unit of GDP) which can also mean producing more "oil scarcity adapted products".

And still, the "oil bill" of the US is very much lowered by US domestic production.

In fact if you consider that European per capita consume around half the oil as Americans (around the case I think), with a consumption similar to Europeans, the US would be around 0 import for oil today.

I estimate that there are about 157 net oil importing countries in the world, and at the current rate of decline in the ratio of Global Net Exports oil to Chindia's Net Imports, in about 18 years the volume of Global Net Exports available to about 155 net oil importing countries would be zero.

OK, that was the answer to the question I did not want to ask. 18 years = zero.

Then what we currently see and what we argue about with regard to the economy is meaningless or will be shortly, followed by another meaningless "we have adjusted" conversation at the next plateau.

Likely we will not have the fuel to wage another global war, sans missiles, but we have enough nuclear power plants that will not cool their own waste to poison the whole f-ing planet.

Brilliant@Q

There is easily enough fuel to wage multiple global wars during the 21st century.

18 years to available net exports reaching zero assumes that current trends remain constant. China and India will not continue blazing forward with double digit growth rates acquiring all of the exported crude oil while the rest of the world does without imported crude oil. Oil exporting countries will have to cut their subsidies for domestic fuel before their exports reach zero which will dampen or end domestic growth. If Westexas would model phase 2 of ELM more realistically, the date would be pushed farther into the future.

I can't see how we can predict with accuracy any outcome.

However, if one assumes everyone will try to maintain BAU, and they will, then 18 years is what we have, as best we can determine. Call this our first choice. I agree it will likely be a longer time frame, likely due to economic problems, but the recent past is all we have to form a guesstimate. All our other societal energy transitions were to higher quality fuels, now we get to do the reverse with a lot more people.

In a longer time frame you must include all the variables, with war being the first option of the second level. How well do we really believe we can wage global war and keep our economy in any semblance of order? I think we might try but I have severe doubts. We have many weapons that are much more accurate, surviving infrastructure will be much less than in the past. Oil will be a target, right alongside offensive weaponry. We are not a rational species, just educated with opposing thumbs.

Of course, I don't think that China & India will actually be consuming 100% of GNE in only 18 years, but on the other hand, the rate of increase in oil consumption in developing countries is one heck of a freight train.

In any case, the endgame, in terms of depletion, is far less important that the depletion we are seeing right now. A rough rule of thumb is that about one-half of post-peak Cumulative Net Exports (CNE) tend to be shipped about one-third of the way into a net export decline period. So, as a rule of thumb, for every three years that we extend the point in time that a country hits zero net oil exports, the 50% post-peak CNE depletion point is only extended by one year.

For example, combined production from the IUKE + VAM Six Country Model* virtually stopped increasing in 1995. They hit zero net oil exports in 2007. One third of the way into the net export decline period, at the end of 1999, they had shipped 54% of post-1995 CNE. Note that 1999 production was slightly higher (at 7.0 mbpd) than 1995 production (6.9 mbpd), and net exports were only down slightly (2.7 mbpd in 1999, versus 2.8 mbpd in 1995), yet the post-1995 "Net Export Fuel Tank" was more than half empty at the end of 1999.

Also, an extrapolation of the 1995 to 2001 decline in the Six Country ECI ratio (ratio of production to consumption), if extrapolated, suggested that they would hit zero net oil exports in 2015, 20 years after production virtually stopped increasing in 1995. They actually hit zero net oil exports in 2007. In other words, An extrapolation of the six year rate of decline in the ECI ratio was too optimistic:

http://i1095.photobucket.com/albums/i475/westexas/NewECIFiles.jpg

The GNE to CNI ratio is very much analogous to the ECI ratio, and an extrapolation of the six year 2005 to 2011 rate of decline in the GNE/CNI ratio suggests that it would hit 1.0, when China & India would theoretically consume 100% of GNE, in 18 years, around 2030. As noted above, a rule of thumb is that for every three years that we extend the theoretical point in time that the GNE/CNI ratio hits 1.0, we only extend the post-2005 Available CNE 50% depletion point by one year.

What has happened is clear. We have seen an epic collapse in the ratio of Global Net Exports of oil to Chindia's Net Imports, falling by more than half in only 9 years, from 11.0 in 2002 to 5.3 in 2011, and the rate of decline in the ratio accelerated to almost 10% per year, from 2008 to 2011, versus the 7%/year rate of decline that we saw from 2002 to 2005.

*Indonesia, UK, Egypt, Vietnam, Argentina, Malaysia

Indonesia, UK, Egypt, Vietnam, Argentina and Malaysia are not representative of the world because you picked them because their productions peaked during the same time frame. Your selection bias accelerates the decline of the group. When considering the world during the next 20 years, there will be countries whose productions will be increasing or roughly constant, such as Canada, Venezuela, Iraq and USA, which will moderate the decline of GNE. These 6 countries were not as economically dependent on the oil revenue as Saudi Arabia which may alter their behavior in phase 2 of ELM. These 6 countries had consumption comparable in magnitude to exports which places the export decline in the region of the inflection point on the falling edge of their production curves. This is where the greatest rate of decline in production lies. The peak production of 4 of them was less than 1 Mb/d. Being nearly 3 Mb/d and comprising about 40% of the total group, the behavior of the UK might be dominating the outcome of the group. No country currently produces 40% of world crude oil production making your extrapolation to world production dubious. UK's production is offshore which has a different production profile (judging from the graphs, declines faster?) than onshore wells.

From the Energy Export Databrowser:

I am not attacking your model, westexas, and intend my post to be constructive criticism. You introduced me to the concept of ELM, and I think it has merit. Exports will decrease faster than production. However, choosing unrealistically pessimistic scenarios will ultimately harm ELM when they are shown to be incorrect. Crude oil will likely continue to be exported in 2030 causing the majority of people to casually dismiss ELM as incorrect and you as a crackpot. That would be a shame considering the brilliance of and effort you have invested in ELM.

"However, choosing unrealistically pessimistic scenarios ..."

Pessimism has an unusual way of becoming reality these days.

One of those graphs caught my eye...Egypt was on a steep net-export crash leading up to "Arab Spring." I tried to look up Syria, Libya, Tunisia, and Yemen but they don't have the net import/export data. It would be interesting to see the data from those places to note if their exports had been demolished as badly as those of Egypt leading up to their revolutions.

It's interesting also to look at the PIIGS nations...Portugal - all imports, drastic increase just before 2000 and maintaining that through 2006ish with a sharp drop-off afterwards. Ireland - all imports, increased through 2008 with drop-off afterward. Italy - mostly all imports, flat since the 90's with accelerating decrease starting around 2000. Greece - all imports, increasing usage until 2006ish, then steep decrease. Spain - all imports, increasing usage until 2007, then steep decrease.

The UK still has a lot of domestic production but is quickly getting itself into a pickle and transitioned to net importer around 2006 in particularly rapid fashion. Still their consumption had been flat since the mid-80's.

France is an interesting case, another one with all imports, but they've had steady consumption since essentially the mid 80's. As they're one of the "stable" EU countries I think it can be assumed they've been working on efficiency and non-oil based strategies of increasing their economy.

Germany, the other "stable" EU country, another all-importer but again steady oil consumption since the mid-80's and starting in 2000 was declining in oil use.

The countries that seem to have gotten themselves into the biggest trouble are the ones that were rapidly increasing their oil usage just before the crash. All except Italy showed that trend of the PIIGS countries - and indeed Italy was the last to catch the "contagion" and has one of the smaller deficits of that group (though one of the highest public sector debts). Germany and France have obviously been growing their economy on efficiency and/or something other than oil.

Actually, I picked them because they were, as of 2011 (BP data base), all members of AFPEC (Association of Former Petroleum Exporting Countries). Also, they are geographically diverse, with differing taxation policies regarding energy consumption, e.g., UK heavily taxes energy consumption, while Indonesia subsidizes energy consumption. Incidentally, Indonesia is struggling to curtail petroleum consumption subsidies, even after they slipped into net importer status.

Also, after their combined production virtually stopped growing in 1995, they showed an "Undulating Plateau," with combined production ranging from 6.9 to 7.0 mbpd from 1995 to 1999 inclusive. In 2001, their combined production was only down to 6.5 mbpd, a simple percentage decline of only 6% from 1995, a six year rate of change of -1%/year. The following sketch shows normalized combined Six Country production and remaining post-1995 CNE (Cumulative Net Exports) by year, with 1995 = 100%:

The above sketch shows how an "Undulating Plateau" in production hid a catastrophic post-1995 CNE depletion rate. Production fell at 1%/year from 1995 to 2001, while the volume of post-1995 CNE fell at 23%/year over the same time frame.

Since production from the top 33 net exporters in 2005 virtually stopped increasing in 2005, I thought that these countries would serve as a useful real world model for GNE (Global Net Exports). In other words, I suspect that Global Net Exports were to 2005 as the Six Country Model was to 1995. And of course, the Six Country Real World Model confirms what the mathematical Export Land Model predicted we would see.

The Six Country data base covers 26 years, from 1986 to 2011, inclusive. If there are any other major net exporters (100,000 bpd or more of net exports) that you are aware of that slipped into net importer status in this time frame, I would be happy to look at including them in the model.

I suppose we could include China in the model, but that would truly distort the model, since China, like the US, slipped into net importer status even as their production continued to increase. As such, the US and China are not representative of the pattern that we expect to see as more and more countries join AFPEC.

But my primary point continues to be that the largest volumetric CNE depletion rate per year is occurring right now. In my opinion, we are only maintaining something resembling BAU because of a sky-high rate of depletion in post-2005 Global CNE and in Available CNE. Whether Saudi Arabia is able to maintain a one mbpd or so of net exports after 2030 doesn't alter the fact that the 2005 to 2011 Saudi data suggest that they may have already shipped, in only six years, more than one-third of their post-2005 CNE.

As noted above, an extrapolation of the six year 1995 to 2001 Six Country data produced an estimated 1995 to 2001 post-1995 CNE depletion rate of 15%/year. The actual 1995 to 2001 post-1995 CNE depletion rate turned out to be 23%/year.

An extrapolation of the rate of decline in the six year 2005 to 2011 GNE to CNI (Chindia's Net Imports) ratio suggests that we may be currently consuming the remaining volume of the total post-2005 supply of net exported oil that will be available to importers other than China and India at the rate of almost 1% per month.

Our data base shows that ANE (Available Net Exports) were 12.8 Gb in 2011. At this rate of consumption, an extrapolation of the 2005 to 2011 data suggest that the remaining supply of post-2005 Available CNE, the cumulative volume of net exported oil that will be available to about 155 net importing countries, would be depleted in about seven years.

As you can see, the seven years from 2030 to 2037 concern me a lot less than the seven years from 2011 to 2018.

The continuing irony of this situation is that the oil importing OECD countries are implementing measures to maintain and encourage consumption, through massive deficit spending, financed by a combination of real creditors and helpful central banks.

"... 1% per month."

Did everyone catch that?

Over a six year time period (1995 to 2001) in which the combined production from the Six Country Model* declined at only 1%/year, the Six Countries were depleting their combined post-1995 CNE (Cumulative Net Exports) at the rate of almost 2% per month.

*Indonesia, UK, Egypt, Vietnam, Argentina, Malaysia

I understand the "export land model", but think these tendancial projections, if good to raise attention to this key aspect, aren't very meaningfull, especially for middle east producing countries : they need to eat as well and buy things (extraction technology being one of them), and haven't much besides oil to pay for imports. Russia would be different in that respect.

But also think we will get into some kind of "discontinuity".

As Westtexas states, ELM is the most relevant issue today. Something has to give, and it isn't going to be the Chinese and their billion plus people - the sheer inertia will smother many if not most of the 156 other oil consumers, that includes the US. I do not believe the US could win an all-out war against China unless nukes were employed and that wouldn't be winning either.

Countdown to zero began yesterday - and 18 years is probably generous.

Sometimes real numbers instead of % give a much clearer picture:

The per capita import of crude is due to the high consumption higher in the USA than in Europe. In addition, energy efficiency (GDP/barrel oil) is much lower.

Of course taxes do not save Europe, however, these taxes have led to an infrastructure in the past that allows to a certain extend the substitution of oil. Working class Europeans pay on avarage less than their US couterparts for commuting, despite/because of these taxes, i.e. many people in Europe do not have to use a car.

Another POV would be economic competitiveness: Do you see any positive correlation between competitiveness and low energy prices? I do not. Or could it in fact be that economies with traditionally high energy prices do better in the current situation? Why?

Do you see any positive correlation between competitiveness and low energy prices? I do not.

Yes, well, I also don't see any positive correlation between "competitiveness" and ultra-low wages on labor, long hours and nonexistent benefits (unless you're a financier who personally benefits from the race to the bottom). Nonetheless, this is the Ayn Rand trickle-down cr*p the American public has swallowed and accepted as gospel for the last 30+ years.

I also don't see any positive correlation between "competitiveness" and ultra-HIGH wages for the financial elites --or for that matter, a positive correlation between "job creators" and actual jobs (at least not jobs for working class Americans anyway).

I also don't see any positive correlation between our voting public and reality, facts, ability to think, or a clue. which of course explains our leaders and what passes for "policy debate" these days.

Unfortunately, public perception in large part determines "reality", or at least what constitutes socially acceptable subject matter and options for policy debate. Over here the Overton Window is simply too small and too far to the right to include Peak Oil, conservation or alternative energy.

I think it is far less complicated than people try to make it.

It all comes down to how much net energy is available to the people.

If we look at the minimum amount of net energy needed for survival we can look at various economies around the world that are just hovering above total collapse. Let us look at North Korea.

Their society is still intact but their people are suffering malnutrition and on the edge calamity.

If we compare that to a modern society we don't have to go far - South Korea. If you look at the extra amount of energy available for economic activities you can estimate around 6 times as much / person.

North Korea - 795 kg of oil equivalent / capita / year

South Korea - 4,990 kg of oil equivalent / capita / year

In reality, humans have a tremendous amount of net energy due to being at the peak of the fossil fuel era and 33 billion barrels of oil per year allows massive economic activity, just not for everyone.

Economies will deal with the net energy decline by moving their people closer to work, dictating the use of smaller cars, then forcing everyone to go back to bicycles and then to horses (actually, they don't have to do anything, this will happen naturally). World population levels will decline according to their ability, or inability to get a good share of these now even more valuable resources.

Resource wars around the globe will be almost continuous for the next 150 years or so until energy balance with nature is reached.

Rich and powerful countries like the US and friends will have the lion's share of these resources due to their powerful militaries. The rich in America and Europe will still have great and luxurious lives while the poor will continue to suffer and die off. It will be a very cut-throat world and we will lose most of our civility in the process, as our history clearly shows.

In summary, prepare yourself not only for a career change to farming but to be able to protect yourselves from groups that didn't prepare.

Good land with great defensive geography. That is what those that wish to prosper should be thinking about.

I disagree. So far at least, the US and most other oil importing OECD countries are being gradually priced out of the market for exported oil, as the developing countries, led by China, consume an increasing share of a declining volume of Global Net Exports of oil (GNE).

We can try to seize foreign oil fields, but transporting that oil to our shores, without a lot of tankers being sunk or damaged is a different matter.

Not yet updated for 2011, but no material change:

It isn't necessarily about "seizing oil fields", today it is a lot about : doing the police job (with allies) along oil routes and producing regions, having oil traded in $, $ as reserve currency, ability to sell treasury bonds. But Iraq and Lybia were clearly primarily about oil (and keeping it in the $ market sphere)

And today if the US wanted to cut oil to China for instance they could.

Then there is the market.

And if China wanted to attack oil tankers bound for the US, they could easily do so, using a variety of methods.

Only because we are still being nice. What do you think will happen when "nice" goes out the window? If our people are starving it will be easy for the next Hitler to come alone and promise to bring us back to glory. That will happen by stealing resources. It is going to get very ugly and those with the biggest, baddest and most bombs are going to win. Do you really think the US Military Industrial Complex is going to just stand by when there is so much to gain? No way. That is like expecting the biggest bully in the schoolyard to not get someone's lunch money when that bully is extremely hungry.

Now, if you can show some historical events that show otherwise, I would like to hear about them.

YvesT and Tankingthinker, the idea that the US would, with their military, just seize foreign oil is absurd. We don't live in that kind of world anymore. Islamic oil nations, or more likely terrorist in Islamic oil nations, could just blow up the oil fields like Saddam did to the Kuwaiti fields. A single terrorist bomb could close any oil terminal.

And what currency oil is traded in has nothing to do with it. I don't know why that old saw keeps coming up. Oil can just as easily be traded in any currency the two trading nations agree upon. They could just agree to swap oil for goats and it would work just fine.

Russia could very easily stop oil even from coming to the ports and sell it, via pipeline to China and other former FSU or Baltic countries.

Any effort by the US to shift oil flow to the US from Africa would only add to the conflict in that continent.

We cannot and will not have the whole world as our enemy despite the wishes of many on this list who seem to believe it is already the case.

Never said it would happen soon, said Iraq and Lybian wars were primarily about oil, that is all.

As to "And what currency oil is traded in has nothing to do with it. I don't know why that old saw keeps coming up. "

What can be said ? "lol" maybe ;)

You really think if the $ wasn't the main trading currency it would be a reserve currency ?

Also chapter 8 and 9 below quite good regarding the basic historical background :

http://books.google.fr/books/about/The_Age_of_Oil.html?id=JWmx5uKA6gIC&r...

Simply stating the name of a book is not any kind of argument, especially if the author of that book is Leonardo Maugeri.

Ron P.

I said for the historical background aspects (not for the "don't beleive in peak oil" aspects)

But if you don't get that the police role the US is playing around oil has as a major consequence or condition, oil traded in $, $ as the reserve currency, what can I say.

You might remember Saddam saying he would trade in Euro or Gadhaffi in yuan or something.

To think that humanity, importing countries or whoever is beyond using violence is not an argument but an opinion.

Using violence or not to secure resources is probably just a matter of cost. Costs obviously come in a number of forms, dollars, lives, political (in) stability, goodwill etc.

Rgds

WeekendPeak

Saddam Hussein switched the trading currency for Iraqi oil to Euros. One of the first things the US did after occupying Iraq was to change the currency back to dollars.

Ron,

If there is anyone more delusional than the Cornucopians, I think it is the people who think the US can use force to bring oil to our shores that we cannot afford to buy in the open marketplace. As you know oil tankers are highly vulnerable to everything from submarines to sabotage, not to mention the inherent vulnerabilities in the entire pipeline and refining infrastructure in the US. Forcing oil to our shores, away from the high bidders in the open marketplace, would be an act of aggression against other oil importing countries, which I don't think would go unanswered.

How many torpedoes are needed to sink an oil tanker?

During the tanker war of the 1980's, oil tankers proved resilient to air-to-ship missiles. Missiles designed to penetrate steel hulls and explode inside the ship did little damage exploding inside a filled compartment of oil because there was no oxygen. There is not much fire and oil leaks out into the ocean. Being underwater a torpedo would make the oil leak out and water rush in, but being compartmentalized, the oil tanker would not sink.

A single missile or torpedo is more effective against a container ship or warship. I am not aware of a laden LNG tanker being struck by a missile or torpedo.

Modern torpedoes are designed to explode under the ship and thus break its back rather than blowing a hole. There are plenty of nice videos on YouTube that show the process in action.

NAOM

Thank-you. I learn something new about torpedoes. The Russian Type 65 (also used by China) is designed to sink large ships, such as aircraft carriers and supertankers.

You are just not thinking nasty enough. I'm talking old school wars. WWI and WWII style wars where almost anything was in play, like firebombing most of the cities in Japan, women and children included.

Firstly, there will likely be a WWII-like alliance that will work together to make sure the resources can be secured. If you don't think the US Military with full use of force, not a police action we have seen, can secure some oil resources then you don't understand what it possible with the military technology that is available. Full force and effort like used in WWII where thousands died every day, not a few thousand died in 10 years. People just forget the scale of what is possible and what humans will resort to when things get bad enough.

When we start down that fossil fuel bell curve there is going to be panic at first then there will be plans made up to secure resources. Countries will group in such a way as to ensure they can keep their people from starving. I guess many still don't understand just how dependent the West is on fossil fuels or don't get just how over populated we are. We can't just give up our industries and go back to the farms. We have a population that is around seven times to big for that!

No, I stand firm on my argument that those with power will steal what is needed and the Middle Eastern countries and their pre-WWII military technology and strength are not going to stand in the way. You talk about sabotage? Well, many armies throughout history had a solution to that - kill everyone. In fact, that was the norm for most of the time man has been at war. Kill the men and take the women and resources. Simple and clean.

You are thinking that people will keep the same amount of civility they had when they had all their luxuries and pampered lives. Did you read The Road? That makes more sense on how people revert back to primal survival instincts. Those that don't will be killed by those that do, just like throughout most of our history.

Oh, we can't get the tankers through to keep our people from starving because Iran has insurgents that keep blowing up the port? General: Clear it completely out for 200 miles and don't leave even an ant alive. Done. Submarines? The Middle East is going to provide a challenge to the US navy? lol. Now that is delusional!

Of course Europe is going to side with the US, as will Canada, Australia, South Korea and Japan. Most likely Russia will as well. China would be committing suicide not to side up. I just don't see why people don't think this could happen easily. The strategy is not only obvious but follows our history and human nature.

Nice is a short-term concept when things are going well.

Food for thought - Earth's population will be less than 1 billion in 150 years. If you think that is going to happen smoothly you really are a optimist. We will burn everything, everywhere and kill everything, just to survive. That is our basic coding and evolution would take thousands of years to change that reality.

You are somewhat delusional about WWII and WWII. In both wars the fighting had been going on for years before the US joined in, and the US only joined because the enemy foolishly started sinking its ships. The main effect was to tilt the balance heavily in favor of the Allied forces. The US could not have defeated the Axis powers without allies - they had already fought the enemy to a standstill even before the US joined.

You are also delusional to think the US would automatically have allies in anything it does. Every country has its own agenda, and that may not be compatible with the US agenda. How many allies did the US have in Iraq? Not even Canada was on side. Britain lined up, but it eventually cost the Prime Minister his job.

WWI was stalemated when the US joined the fight, but WWII is a different story. Germany was advancing into Russia and Japan was advancing into China when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Japan made major advances after the US entered the war: Indochina, Philippines, Malaya, Dutch East Indies, Burma. Germany would likely have gotten bogged down in Russia (how soon without US aid to Russia is an open question), but they had a very firm grip on Europe. Japan would also likely have eventually gotten bogged down in China, but that would not have defeated them. Britain was barely hanging on, but if Germany had managed to take or block the Suez and/or Japan had taken much of India, Britain's future would have been grim. It did take the total resources of the Allies to defeat the Axis, but the Axis had not been brought to a standstill before the US became an active participant in the war.

About wwI and II we can also remember the huge importance that oil already played in these wars, for instance Hitler having Baku (after Romania) as his main target :

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rGzEs3K66hA

And also the fact that the US have been selling oil(and other things) to both sides quite long during the two wars..

As to a possible new "world war" around the middle east, to me in any case, it would clearly not be "middle east countries against the rest", more some alliances fighting over the middle east (and fight between middle east countries part of one or another alliance), as more or less already the case.

But not so sure that will happen, a kind of "generalized civil war" could also be the outcome.

"You are somewhat delusional about WWII and WWII"

Actually, those wars are well documented. You can spend a lifetime just reading about them.

Many still think the US was an innocent bystander when Japan attacked. Not true. The US put up a blockade that was putting the brakes on Japan's war efforts. Yes, they were being squeezed by reduced oil supply. Huh, that black gold is amazing.

Hitler also needed Russian oil fields to power their war machine.

You are comparing global resource wars over Bush's Iraq war? lol. Then you call me delusional? lol. Excellent!

No, the coming resource wars are going to be far more serious than a huge power fighting against a tiny one. It will probably start off as such and then grow as countries take sides. Again, history shows that going against the US in a full out war is a losing proposition.

Don't even bring up cold wars like Korea or Vietnam. These were simple cold war battles and both sides decided to back off before WWIII started. I am talking about WWIII driven by the actual survival of countries.

Mixing full out efforts like WWI and WWII and comparing them to Korea, Vietnam and Iraq show a lack of understanding of what humans will do when they put into a corner, when things get desperate and nasty.

Things are going to get nasty. It is like putting a group of men in a locked stadium and putting in a set amount of food. Once they understand that they have to kill to survive, they will. The strong will team up and take from the weaker groups and individuals. Once the deaths start to rack up, all hell breaks loose with eventually one last man standing.

This is the situation as we enter the second half of the fossil fuel era. This is not about political or religious ideology but about survival. Earth can only hold less than about 1 billion people (much less if they want to live very comfortably). It is not just about energy but about all the other supporting resources like ocean fisheries, forests, clean air, clean fresh water, metals, minerals, etc.

Balance will be achieved, sooner or later.

In 1939, in the biggest battle you never heard of, the Battle of Khalkhin Gol, the Russian Siberian division wiped out the Japanese Manchurian division on the Mongolian border.

Although the Japanese were surrounded, they refused to surrender, so the Russians just killed them all. There are no good estimates of casualties since both sides lied, but most likely 17,000 Russians and 50,000 Japanese were killed. It was the biggest tank battle in history to that time - the Russians fielded about 500 tanks and they were far superior to the Japanese tanks.

It scared the wits out of the Japanese - they never attacked the Russians again -, so they switched from Plan A, conquer Mongolia and Siberia, to Plan B, conquer the South Pacific. This brought them into conflict with the US, and apparently they had learned nothing from fighting the Russians, so they attacked the US, at which point your story begins.

The Russians had learned a lot, however, so when the Germans invaded them, they brought their Siberian division West and threw them at the Germans in Battle of Moscow, forcing the German troops to retreat and killing many of them. The Germans turned out to be slow learners, too, so the Russians used their Mongolian techniques against them at the Battle of Stalingrad and destroyed the entire German Sixth Army. In all, 80% of German casualties occurred on the Eastern Front.

In between, Britain sank 50% of the German destroyer fleet in the Battle of Narvik, and crippled the Luftwafte during the Battle of Britain, ending the German capability for invading Britain. Hitler, too, switched to his Plan B, invade Russia, which was no more well thought out than the Japanese Plan B.

So, at this point, the US was attacked by Japan and entered the war. However, from the Russian and British perspective the war was half over by this time - they had already brought the Axis invasions of their countries to a halt, but they lacked the capability to bring the war to an end by invading Germany and Japan - which problem the US solved.

Note that I am not looking at this from the American perspective. My father was in the Canadian Army repairing damaged tanks England, my uncle was in the Royal Canadian Air Force bombing Germans everywhere there were Germans to bomb, and my wife's father was in the RAF flying secret supplies to the French Resistance fighters. Many of their friends were in the Canadian or British Navy, running escort duty for convoys of Canadian supplies heading to England. They all felt the U S was very late getting into the war.

I hear this "strategic" nonsence about why Germany or Japan lost WW II on and on. The ratio of casualties of the German Wehrmacht regarding the Red Armie was about 1 to 2-4. Germany lost about 3 million soldiers on the Eastfront while the Soviet Union lost about 7 million. Even in Stalingrad the casualties ratio was about 1 to 1 (1 million each including allies for the whole operation). When their was a strategic deficit of the Wehrmacht, than it was their considerably higher weather-related problems because of the russian winter, including both soldiers (e.g. clothes) and technic vehicles.

But the main reason Germany - after their initial moment of inertia - was defeadet by the Russians was of demografic nature. Germany attacked when Russia had their democrapic all-time high. The relevant birth cohorts in russia of the 1920's reached 4 million per year, whereas the German yearly birth cohorts where only a a little over a million.

Stalin had more than 20 million soldiers at his hand. He sacrified millions because he could afford that casualties. Germany could not. The longer the war went on, the more this demograpic superioty came into action. The western front did not help this. At the high time Germany had nearly 5 million soldiers on the east front, the Soviet Union more than 10 million. The Soviet Union lost nerlay 20 million people in "The Great Fatherland War" of which 13 million where civilians. Germany lost about 6 million of which 3.5 million where soldiers. By the way - the US of A lost about half a million in WW II and 60.000 in Vietnam. At the end of WW II the US of A build fregates faster than the Japanese built torpedos. No mystic strategic "Vodoo", just industrial and demographic superiorty!

In nearly every historic discussion demograpic reality is ignored or vastly underestimated, see Antic Rom, Greece, ...

I wonder about timing. The US still has a LOT of coal so they aren't going to be starving anytime soon, especially since it's the world's breadbasket. I wonder if they'll just put their efforts into CTL instead. I can't see how it would take more than 10 years to ramp that up to something that could allow the country to continue functioning at a rudimentary level. All they need is the right motivation, and losing the right to import oil would certainly provide that. For Americans' sakes, I sure hope the financial system collapses soon rather than later, while they are still the #3 oil producer, so they'll at least have some domestic oil left to power the transition to coal. And by the time the US runs out of coal, the Middle East's oil will likely be long gone.

"I wonder if they'll just put their efforts into CTL instead."

I wonder about this as well. Doesn't appear to be too much activity ..... yet.

Perhaps, but based on the evolutionary history of our planet there is no guarantee that Homo idioticus will be a part of that new and improved balanced ecosystem.

http://i289.photobucket.com/albums/ll225/Fmagyar/coping.jpg

"After a week of hard fighting, Coalition forces took Mombasa and began to advance up the main highway toward Nairobi, while the battered US divisions and their Kenyan allies retreated before them. The Kenyan president fled to Kisumu, in the far west of the country, with his mistress and his cabinet. Jets still screamed south from US bases in the Persian Gulf to tangle with Chinese fighters based in half a dozen African countries, and land-based cruise missiles and B-52s from Diego Garcia pounded anything that looked vaguely like a military target, but it was hard for anyone to miss the fact that the US was losing the war."

http://thearchdruidreport.blogspot.com/2012/10/how-it-could-happen-part-...

You imply that N. Korea is functioning at near minimal net energy need. How much 'energy' do you think it might gain if it did not have a military. I am not arguing if this is a realistic assumption, but many countries in this world spend an inordinate amount of energy on their military forces.

Don

I guess I picked a good time to finally begin reading "Collapse" by Jared Diamond then.

I don't know the right answer but the obvious answer seems to lack some context.

The European prices are due to higher taxes. These taxes buy public goods in these same countries.

A significant share of the new, higher prices are exported to oil producers

I like your work - some use of statistics seems a little naive:

For example the graph you show of 'employment' is this FT or all, in the UK only 25% of the working age population has a FT job, the recent drop in US unemployment U3 was not reflected in U6...

In the US you have had wage deflation plus aggressive outsourcing for at least a decade longer than in Europe so I imagine the structural employment problems are worse.

As I'm sure you know the real unemployment rate is ~23% and that is in a country with no universal means tested cash benefits - unlike the UK and much of Europe.

We are in an economic war with our masters and they control the media for example according to the UK's mass media we are in an age of austerity BUT the government borrowed >20% more than last year, of course this may in part have something to do with the also >20% decrease in North Sea revenues over the same period.

Rice Farmer has just posted up 'Special Issue "New Studies in EROI (Energy Return on Investment)"'

http://www.mdpi.com/journal/sustainability/special_issues/New_Studies_EROI

Looks good reading if you have any interest in EROEI or EROI ;-)

My blog:

http://slightlypreoccupied.blogspot.co.uk/

This looks a bit afterthought-ed in. There are plenty of places in the US/Mexico and other non-Asia places where you could make that argument. A more plausible reason is a "long-age of expectations" clash. In the US we expect to have an environment that isn't completely toxic from straight-piped industrial waste and we expect to have reasonable and safe working conditions. Beyond that the US expects to live in rather large houses with climate control, electricity, and running water and most also expect to have personal automotive transportation. There are other things Americans expect, obviously, but those are biggies. So I'd say the cost of goods produced in Asia is not climate driven, but due to starting from a lower point with different expectations.

This comment is really too short, but I was trying to write a post of 1,000 or so words, and didn't have room for a good explanation.

I had talked about this a little bit more in The Close Tie Between Energy Consumption, Employment and Recession (which is not on TOD).

There are really a number of issues, and what you describe is part of them. Starting with a colder climate, Northern Europe and later America stumbled into using fossil fuels early on, because trying to heat our homes was leading to deforestation and not enough fuel for everyone. As we learned to use fossil fuels, we built up a whole culture around them. We made big sturdy cars, too, rather than bicycles, partly justifying this based on the fact that in some places, it is too cold for bicycles in winter. The early use of fossil fuels also made us rich enough to build big sturdy houses, which people needed high salaries to pay for.

The globally warmer countries generally did not ramp up their fossil fuel use as much. Part of this may have been the fact that they did not have as much of a need for supplemental energy to keep their homes warm. Homes could also be built in a much less sturdy fashion.

About fossile fuels usage yes maybe you could say so, first major use of fossile fuel is peat in Holland I think, then coal in England and very soon after in continental Europe.

As to houses, would say that houses tended to be more "sturdy" in southern europe than northern one (and also the case compared to current American ones in fact), for instance in France, southern old houses are always plain stones and sometimes really thick (also true in Spain, Italy or even Libanon for instance) whereas in Normandy it was more "wood structure with mud and straw", and with coal, bricks became also very common. Scandinavian traditional houses are also more wood I think.

But also a lot of cultural aspects, in many Chinese regions the climate is also very harsh, also true in Japan, but wood always has been a major part in construction (not only).

But for sure the case compared to tropical climates.