Ten Reasons Why High Oil Prices Are a Problem

Posted by Gail the Actuary on January 29, 2013 - 5:39am

A person might think from looking at news reports that our oil problems are gone, but oil prices are still high.

In fact, the new “tight oil” sources of oil which are supposed to grow in supply are still expensive to extract. If we expect to have more tight oil and more oil from other unconventional sources, we need to expect to continue to have high oil prices. The new oil may help supply somewhat, but the high cost of extraction is not likely to go away.

Why are high oil prices a problem?

1. It is not just oil prices that rise. The cost of food rises as well, partly because oil is used in many ways in growing and transporting food and partly because of the competition from biofuels for land, sending land prices up. The cost of shipping goods of all types rises, since oil is used in nearly all methods of transports. The cost of materials that are made from oil, such as asphalt and chemical products, also rises.

If the cost of oil rises, it tends to raise the cost of other fossil fuels. The cost of natural gas extraction tends to rises, since oil is used in natural gas drilling and in transporting water for fracking. Because of an over-supply of natural gas in the US, its sales price is temporarily less than the cost of production. This is not a sustainable situation. Higher oil costs also tend to raise the cost of transporting coal to the destination where it is used.

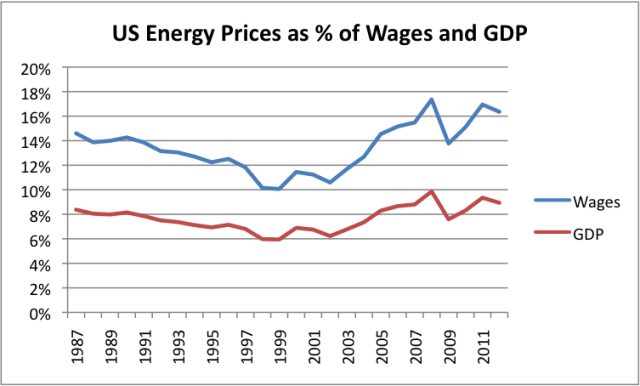

Figure 2 shows total energy costs as a percentage of two different bases: GDP and Wages.1 These costs are still near their high point in 2008, relative to these bases. Because oil is the largest source of energy, and the highest priced, it represents the majority of energy costs. GDP is the usual base of comparison, but I have chosen to show a comparison to wages as well. I do this because even if an increase in costs takes place in the government or business sector of the economy, most of the higher costs will eventually have to be paid for by individuals, through higher taxes or higher prices on goods or services.

2. High oil prices don’t go away, except in recession.

We extracted the easiest (and cheapest) to extract oil first. Even oil company executives say, “The easy oil is gone.” The oil that is available now tends to be expensive to extract because it is deep under the sea, or near the North Pole, or needs to be “fracked,” or is thick like paste, and needs to be melted. We haven’t discovered cheaper substitutes, either, even though we have been looking for years.

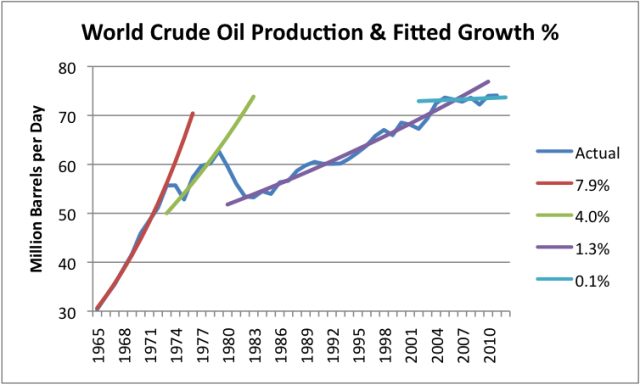

In fact, there is good reason to believe that the cost of oil extraction will continue to rise faster than the rate of inflation, because we are hitting a situation of “diminishing returns”. There is evidence that world oil production costs are increasing at about 9% per year (7% after backing out the effect of inflation). Oil prices paid by consumers will need to keep pace, if we expect increased extraction to take place. There is even evidence that sweet sports are extracted first in Bakken tight oil, causing the cost of this extraction to rise as well.

3. Salaries don’t increase to offset rising oil prices.

Most of us know from personal experience that salaries don’t rise with rising oil prices.

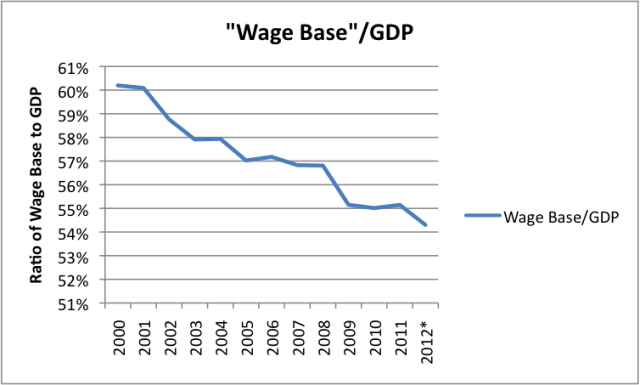

In fact, as oil prices have risen since 2000, wage growth has increasingly lagged GDP growth. Figure 3 shows the ratio of wages (using the same definition as in Figure 2) to GDP.

If salaries don’t rise, and prices of many types of goods and services do, something has to “give”. This disparity seems to be the reason for the continuing economic discomfort experienced in the past several years. For many consumers, the only solution is a long-term cut back in discretionary spending.

4. Spikes in oil prices tend to be associated with recessions.

Economist James Hamilton has shown that 10 out of the last 11 US recessions were associated with oil price spikes.

When oil prices rise, consumers tend to cut back on discretionary spending, so as to have enough money for basics, such as food and gasoline for commuting. These cut-backs in spending lead to lay-offs in discretionary sectors of the economy, such as vacation travel and visits to restaurants. The lay-offs in these sectors lead to more cutbacks in spending, and to more debt defaults.

5. High oil prices don’t “recycle” well through the economy.

Theoretically, high oil prices might lead to more employment in the oil sector, and more purchases by these employees. In practice, this provides only a very partial offset to higher price. The oil sector is not a big employer, although with rising oil extraction costs and more US drilling, it is getting to be a larger employer. Oil importing countries find that much of their expenditures must go abroad. Even if these expenditures are recycled back as more US debt, this is not the same as more US salaries. Also, the United States government is reaching debt limits.

Even within oil exporting countries, high oil prices don’t necessarily recycle to other citizens well. A recent study shows that 2011 food price spikes helped trigger the Arab Spring. Since higher food prices are closely related to higher oil prices (and occurred at the same time), this is an example of poor recycling. As populations rise, the need to keep big populations properly fed and otherwise cared for gets to be more of an issue. Countries with high populations relative to exports, such as Iran, Nigeria, Russia, Sudan, and Venezuela would seem to have the most difficulty in providing needed goods to citizens.

6. Housing prices are adversely affected by high oil prices.

If a person is required to pay more for oil, food, and delivered goods of all sorts, less will be left over for discretionary spending. Buying a new home is one such type of discretionary expenditure.

US housing prices started to drop in mid 2006, according to data of the S&P Case Shiller home price index. This timing fits in well with when oil prices began to rise, based on Figure 1.

7. Business profitability is adversely affected by high oil prices.

Some businesses in discretionary sectors may close their doors completely. Others may lay off workers to get supply and demand back into balance.

8. The impact of high oil prices doesn’t “go away”.

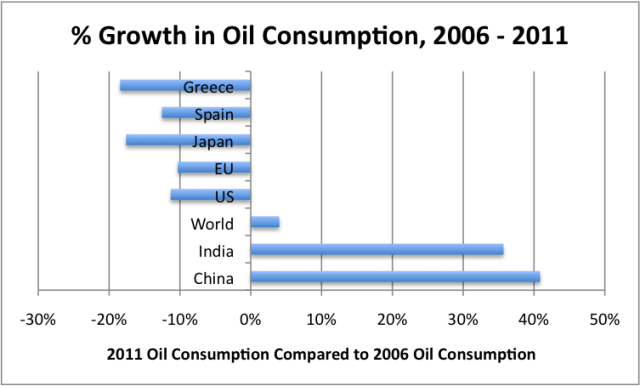

Citizens’ discretionary income is permanently lower. Businesses that close when oil prices rise generally don’t re-open. In some cases, businesses that close may be replaced by companies in China or India, with lower operating costs. These lower operating costs indirectly reflect the fact that the companies use less oil, and the fact that their workers can be paid less, because the workers use less oil. This is a part of the reason why US employment levels remain low, and why we don’t see a big bounce-back in growth after the Great Recession. Figure 4 below shows the big shifts in oil consumption that have taken place.

A major part of the “fix” for high oil prices that does takes place is provided by the government. This takes the place in the form of unemployment benefits, stimulus programs, and artificially low interest rates.

Efficiency changes may provide some mitigation, as older less fuel-efficient cars are replaced with more fuel-efficient cars. Of course, if the more fuel-efficient cars are more expensive, part of the savings to consumers will be lost because of higher monthly payments for the replacement vehicles.

9. Government finances are especially affected by high oil prices.

With higher unemployment rates, governments are faced with paying more unemployment benefits and making more stimulus payments. If there have been many debt defaults (because of more unemployment or because of falling home prices), the government may also need to bail out banks. At the same time, taxes collected from citizens are lower, because of lower employment. A major reason (but not the only reason) for today’s debt problems of the governments of large oil importers, such as US, Japan, and much of Europe, is high oil prices.

Governments are also affected by the high cost of replacing infrastructure that was built when oil prices were much lower. For example, the cost of replacing asphalt roads is much higher. So is the cost of replacing bridges and buried underground pipelines. The only way these costs can be reduced is by doing less–going back to gravel roads, for example.

10. Higher oil prices reflect a need to focus a disproportionate share of investment and resource use inside the oil sector. This makes it increasingly difficult maintain growth within the oil sector, and acts to reduce growth rates outside the oil sector.

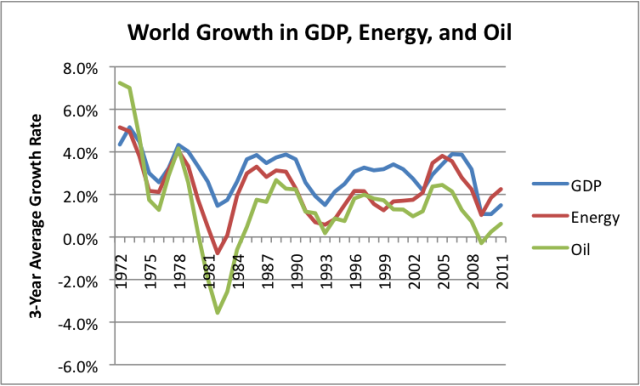

There is a close tie between energy consumption and economic activity because nearly all economic activity requires the use of some type of energy besides human labor. Oil is the single largest source of energy, and the most expensive. When we look at GDP growth for the world, it is closely aligned with growth in oil consumption and growth in energy consumption in general. In fact, changes in oil and energy growth seem to precede GDP growth, as might be expected if oil and energy use are a cause of world economic growth.

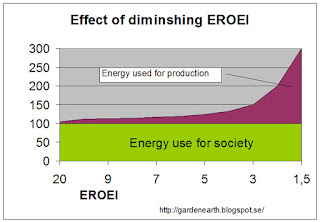

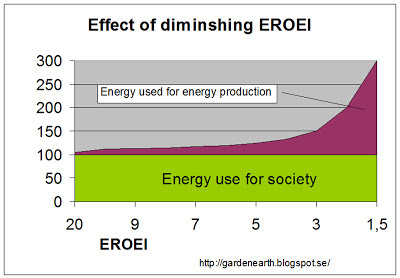

The current situation of needing increasing amounts of resources to extract oil is sometimes referred to one of declining Energy Return on Energy Invested (EROEI). Multiple problems are associated with declining EROEI, when cost levels are already high:

(a) It becomes increasingly difficult to keep scaling up oil industry investment because of limits on debt availability, when heavy investment is made up front, and returns are many years away. As an example, Petrobas in Brazil is running into this limit. Some US oil and gas producers are reaching debt limits as well.

(b) Greater use of oil within the industry leaves less for other sectors of the economy. Oil production has not been rising very quickly in recent years (Figure 6 below), so even a small increase by the industry can reduce net availability of oil to society. Some of this additional oil use is difficult to avoid. For example, if oil is located in a remote area, employees frequently need to live at great distance from the site and commute using oil-based means of transport.

(c) Declining EROEI puts pressure on other limited resources as well. For example, there can be water limits, when fracking is used, leading to conflicts with other use, such as agricultural use of water. Pollution can become an increasingly large problem as well.

(d) High oil investment cost can be expected to slow down new investment, and keep oil supply from rising as fast world demand rises. To the extent that oil is necessary for economic growth, this slowdown will tend to constrain growth in other economic sectors.

Airline Industry as an Example of Impacts on Discretionary Industries

High oil prices can be expected to cause discretionary sectors to shrink back in size. In many respects, the airline industry is the “canary in the coal mine,” showing how discretionary sectors can be forced to shrink.

In the case of commercial air lines, when oil prices are high, consumers have less money to spend on vacation travel, so demand for airline tickets falls. At the same time, the price of fuel to operate airplanes rises, making the cost of operating airplanes higher. Business travel is less affected, but still is affected to some extent, because some long-distance business travel is discretionary.

Airlines respond by consolidating and cutting back in whatever ways they can. Salaries of pilots and stewardesses are reduced. Pension plans are scaled back. New more fuel-efficient aircraft are purchased, and less fuel-efficient aircraft are phased out. Less profitable routes are closed. The industry still experiences bankruptcy after bankruptcy, and merger after merger. If oil prices stabilize for a while, this process stabilizes a bit, but doesn’t really stop. Eventually, the commercial airline industry may shrink to such an extent that necessary business flights become difficult.

There are many discretionary sectors besides the airline industry waiting in the wings to shrink. While oil prices have been high for several years, their effects have not yet been fully incorporated into discretionary sectors. This is the case because governments have been able to use deficit spending and artificially low interest rates to shield consumers from the “real” impacts of high-priced oil.

Governments are now finding that debt cannot be ramped up indefinitely. As taxes need to be raised and benefits decreased, and as interest rates are forced higher, consumers will again see discretionary income squeezed. New cutbacks are likely to hit additional discretionary sectors, such as restaurants, the “arts,” higher education, and medicine for the elderly.

It would be very helpful if new unconventional oil developments would fix the problem of high-cost oil, but it is difficult to see how they will. They are high-cost to develop and slow to ramp up. Governments are in such poor financial condition that they need taxes from wherever they can get them–revenue of oil and gas operators is a likely target. To the extent that unconventional oil and gas production does ramp up, my expectation is that it will be too little, too late, and too high-priced.

Note:

[1] Wages include private and government wages, proprietors’ income, and taxes paid by employers on behalf of employees. They do not include transfer payments, such as Social Security.

This post originally appeared on Our Finite World.

There seems to be a current perception of oil supply and price having leveled off with people having made the necessary adjustments needed for the economy to be stable at least for a while. However, your comments above reflect my concerns that when OECD govt's stop taking on huge debt, those economies will sharply contract.

The postponed face off between Obama and Congress over the budget, now looms a few months away, but the writing's on the wall that attempts will be made to at least get closer to a balanced budget and when that happens it will be very interesting to see what the economic knock on effects will be. Not good I'm sure.

You and I see pretty much the same thing. I put together my forecast for 2013 (or maybe it somehow can be pushed into 2014) in a post I didn't submit to TOD:

2013: Beginning of Long-Term Recession?

I put the chance for another recession at 20% or below. While taxes are increasing modestly, I doubt that we will see much debt reduction. The economists will gladly point to Britian as an example while steep cuts (austerity) is bad. The President did say that he expects that there will be more cuts to Medicare. A significant portion of Medicare spending is "wasted" keeping people alive in the last months of their life. Both political parties have politicized this, but this is the most likely place to find savings. Such cuts would have little impact on the economy (it would just slow the growth of the health care industry) since it does not keep people alive so that they can be productive again.

Furthermore, while the Federal Govt. will try to make additional cuts, the private sector has been paying down dept (including personal debt) which will free up the possibility for individuals to begin spending more again. I think that this could offset any affect that spending changes by the Federal Govt. could have.

The key thing is crude oil prices. Will crude oil increase dramatically? If so, that could drive us back into recession. The yearly increase in crude oil prices is around $10/bbl. If this continues, I don't think that it will cause a recession, just continued slow growth - higher increases is a different matter.

The best part of that is that the Tea Party-On Dudes who were having head explosions on pretty much a daily basis about Obamacare's "death panels" will have no problem going to the ends of the earth forcing and justifying Medicare cuts. They will be, in effect, all for instituting actual death panels (i.e. we don't need to spend anymore on end of life care for this person) rather than those dreamt up in the right wing paranoid delusion flavor of the week.

Notice how a certain state government recently decided to cut hospice care due to "austerity" measures. Understandable - the oligarchy has no problem letting people live without dignity - why should their last few days / months in existence be any different ?

To me I see only two paths- 1)debt default/deflation, 2) debasement of currency - the functions/mechanisms for this to happen are opaque to me, so I would love to hear Gails inputs.

1) Debt default/deflation. This is what world governments are trying to avoid. Meridith Whitney made a compelling case for massive municipal bond default a couple of years ago, but this has been delayed by the political sector. The politic sector is stuck in the "Election Land Model" (Sorry Jeffery - ELM - the best I could do ) but in all seriousness they are looking to keep their jobs first and foremost. All actions to date are to kick the debt/default can down the road and keep their jobs. 2006-2007 housing ponzi dynamics are complicating their actions and high oil prices are functioning like an ever increasing tax most of which literally goes up in smoke, with no residual long term store of value (products). Energy to light our streets at night is gone in a flash, energy used to say produce a piece of furniture has a long term store of value if it is well made and functional long term.

2) currency debasement. This is where I think we will end up. I see no other way to address all the financial promises and guarantees that have been made. In the final examination it is (currently) political suicide to massively cut programs and pensions. With the Fed buying treasuries the mechanism is in place to print without having to borrow from foreign sources or to pay reasonable interest on US gov debt. There will be lots of political drama claiming doom, temporary extensions, and promised resolution will be 3 months away(wash, rinse, repeat). Victory will be claimed by some who reduce the rate of debt expansion.

It is how this will trickle down into the voters pockets that is not clear to me. Sans overthrows and dictatorships, appeasing a large enough group of people people who are financially hurting to get elected will be the name of the game in my Election Land Model. The political arena is where we will be increasingly focused for answers. Bottom line the politicians will be looking at getting elected. They do not lead but attempt to stay ahead of our financial desires.

Must watch-

http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2013-01-04/how-fiat-currency-leads-collect...

"Sans overthrows and dictatorships, appeasing a large enough group of people people who are financially hurting to get elected will be the name of the game in my Election Land Model."

http://www.truthdig.com/report/item/white_power_to_the_rescue_20130128/

White Power to the Rescue

last paragraph from your link-

"There are ample historical records that disprove the myths espoused by the neo-Confederates, who insist the Civil War was not about slavery but states’ rights and the protection of traditional Christianity. But these records are useless in puncturing their self-delusion, just as documentary evidence does nothing to blunt the self-delusion of Holocaust deniers. Those who retreat into fantasy cannot be engaged in rational discussion, for fantasy is all that is left of their tattered self-esteem. When their myths are attacked as untrue it triggers not a discussion of facts and evidence but a ferocious emotional backlash. The challenge of the myth threatens what is left of hope. And as the economy unravels, as the future looks bleaker and bleaker, this terrifying myth gains potency."

This is the stuff of nightmares. Unfortunately, I have observed this in certain individuals at times and he is quite correct you cannot argue with a persons deluded fantasy, much like a chinese finger trap the harder you try the worse it gets.

"It is how this will trickle down into the voters pockets that is not clear to me."

It was never meant to. It's all about plugging holes in banks' balance sheets and propping up the value of their paper assets, which have been leveraged to many times their true market value, and to shore up against these assets being marked to market. This is why I've determined that we will see a deflationary period; we must because virtually everything of real value has been leveraged so far beyond its intrinsic worth. Zombie money doesn't circulate like true capital. It's a fundamentally corrupting process.

Illargi's latest: How To Spot A Zombie

He goes on:

Weather it's our financial system or our relationship to real capital (resources), it occurs to me that it comes down to too many current and future claims on declining real resources and the delusion that we can substitute imaginary resources for them. This why we see such a remarkable feeding frenzy over things we can dig up or pump out of the ground. That said, everything gets "marked to market" eventually. When this occurs, far too many humans will be faced with having to fight over what remains of anything with intrinsic value, and that won't be much, it seems.

Agreed on where we have been but looking forward, sans overthrows and dictatorships, those same politicians helping the bankers are going to need votes. Money can buy a politician but not an election.

Romney vs Obama-

CMAG's preliminary estimate of $479 million to $396 million, but Obama's campaign either held its own or retained the edge in many aspects of the air war.

http://adage.com/article/campaign-trail/romney-outspent-obama-advertise/...

"We the people" will choose the direction we go, the politicians can only hope to stay out in front. They need our votes, so we decide. We will choose to avoid the pain of fiscal responsibility. When the time comes it will be easier to extend and pretend with the hope that someone other than us will pay.

http://www.zerohedge.com/news/2013-01-04/how-fiat-currency-leads-collect...

I'm not sure I would count on deflation. The whole point of the Fed buying MBS at face value to the tune of $50B a month is to slowly bury the mortgage losses on their balance sheet. That coupled with the ability of corporations to continue to refinance at ever lower interest rates is doing a great job of preventing the losses from reaching the holders of capital which then leaves them in a position to bid up more assets.

I guess I see a third possibility--some kind of discontinuity, so the currency, for example, does not really buy much in the way of international goods any more. There will be currencies, but they will be closer to local currencies.

We saw the Soviet Union become the Former Soviet Union. Quite a few of us would not be shocked to see the Eurozone become the Former Eurozone. There is nothing etched in stone that the make-up of the United States has to remain as it is. A state or area that is doing better than the rest could decide they want to pick up and leave, just as Catalonia wants to leave Spain. With changes of this type, the US dollar may not remain the reserve currency. International trade could be fairly different, it would seem.

Gail,

What you suggest would indeed seem likely at some future point when sections of the US or the euro zone decide they are better to go it alone. I would think this is most likely in the euro zone as they were independent not that long ago.

For the US I would think this would need something fairly dramatic, like a complete collapse of the US Federal government. Making any state feel like it is better off without the Federal government like you suggest would be a financial one, but would likely require a weak Federal government. I would think this would lead to money printing first as the Fed would try to hang on with as much assistance as possible, leading to debasement, leading to dissolution of the union, and then the rise of local currencies.

I see deflation in non essentials, inflation in essentials, and the best plan is Westexas's recommendations abut getting to the non discretionary side of the economy. But with the US economy based so much on non essentials we are seeing high and likely rising unemployment. Cutting food stamps, SS, medicare, and other assistance will be political suicide. I see no other option in the near future other than debasement. Debasement isn't good for anyone but I can see it being viewed as the least bad option.

A wake up moment of a bank holiday or bond market collapse has basically been decided against so far. The rules on marking anything to market are being ignored. The Federal reserve is buying MBS every month. Looks like extend and pretend is the key and politically favorable option. Romney and his people had some fairly snarly comments about peoples dependance on government money, I think this cost him the election.

The powers that be are trying to avoid anything that might start a panic. The recent sales of firearms as an indicator of the mood of the people. Mention taking away gun rights people will panic and buy arms. It is on the TV every night, empty shelves at gun stores. People are worried, they watched New Orleans, they know despite all the happy talk the economy is not getting as good as the msm tries to tell you it is. Against all of this try taking entitlements away from suffering people while giving bankers huge bailouts. The average Goldman bonus was $400k, and you want to cut my food stamps and get re-elected? The government is backed into a political corner, they have to print imho.

What happens if housing prices are allowed to fall significantly from this juncture? How many people then are underwater? How will they react? Is this why they are propping up banks and home prices, extending and pretending, not forcing housing to be marked to market. I think we have reached an infliction point. The public has its back against the wall, they are edgy and panicky. I think printing is being viewed as the least painful option today, right now. It is conveniently (intentionally?) obscure, but it is there. I don't go in for huge conspiracies, and beside so much of this is really in your face, I think it is our collective denial and hope. Obama used the word hope during his first election, as if that was something you could tie your wagon to, and it worked. I think that tells us where we were. I think desperation comes after hope. Desperation allows you to ignore accounting rules and mark to market. Desperation allows you to borrow from your own central bank to fund government. I don't expect much more deflation before they really try and stimulate the economy.

International trade without the global green back would be dificult at best.

- an anecdotal international trade story- Friend of my wife went to Mexico to learn all about a factory the company she works for operates there. What the people who worked there did not know is that this factory will be closed down and operations moved back to the US. What also wasn't shared was that automation will reduce the amount of jobs by almost 90%.

A few links regarding when sections of the US ... decide they are better to go it alone.

http://vermontrepublic.org/

http://www.vtcommons.org/blog/spark-flare-wildfire-lierre-keith-vermont-...

VT is the one I have been following. Here are some more, of varying seriousness:

http://io9.com/5923080/10-movements-to-secede-from-the-united-states

Don't worry prices will soon fall because there is a worldwide oil glut. Proof can be found in this well researched and thought out economic blog post.....

http://econintersect.com/wordpress/?p=32437

P.S. I hope the sarcasm dripping off my keyboard comes through in the typing of the above statement. I was searching for what is really going on with the Seaway pipeline expansion hiccups when I clicked on this drivel. I thought about posting a comment on some inaccuracies in the post but was unable to figure out where to start.

w - I'm trying to get some details on Seagate from some semi-insiders. It's more than an academic interest to me. I sell my Texas crude in Lake Charles pegged to Light La. Sweet prices and not WTI. With the Seagate on and off again delivery reports LLS has been on something of a rolleroaster: $112/bbl down to under $95/bbl and now back up to $110/bbl. And the WTI sellers are watching closely also. The differential between WTI and LLS/Brent has decreased significantly. Last time I checked the differential between WTI and Brent fell about 40%.

And as they say down on the farm: you ain't seen nothing yet. They expect to have two new oil lines coming down the existing ROW that may be bring an additional 600K to 800k bopd down to the Gulf Coast from Cushing in two years. Pipelines that require no fed permission. The Canadians will be thrilled to see their market expand. The rest of us...not so much

My opinion is that LLS is at present more closely linked to international oil prices;essentially Brent and Dubai, which are the basis prices off which pretty much everything else (ex WTI/Bakken/WCS) gets priced.

However, with Cushing increasingly unblocked(and therefore, to a certain extent, Bakken and Canada) you are likely to see a quite sharp drop in LLS pricing as it comes more in line with WTI Cushing-based prices. Unblocking Cushing will raise WTI prices somewhat, but with US ban on crude oil exports it's possible that US (and therefore Canadian) crudes will price somewhat below international crudes, for as long as Bakken and Canadian crude or syncrude production is rising.

I suspect Canada will wish to use the US Gulf Coast to export its own production to a wider global market, though really I think they need to access the Pacific Basin directly. Canadian exports via the Gulf Coast could create some interesting back-haul opportunities for oil tankers currently shipping crude east>west. Ultimately it's all about crude qualities required by refineries... I guess the Canadians can create more or less whatever quality syncrude is required, within reason...??

For you guys pricing production off LLS, the hit will be unpleasant, but nowhere close to the massive cut in earnings for mid-west refiners as WTI reprices higher. No comfort for you, ROCKMAN, I know...

Very much off the cuff thoughts... be interested for TODers to pick holes....

NFE – Here are someone’s thoughts on those potential problems: http://www.rbnenergy.com/after-the-flood-light-sweet-crude-pricing-beyon...

“After the Flood – Gulf Coast Light Sweet Crude Pricing Beyond 2013: A veritable flood of more than 3 MMb/d of new crude production from the US and Canada will come into the Houston region by 2015 via long awaited new pipeline infrastructure. The most immediate impact will be to back out light sweet crudes from the Gulf Coast region – as early as 2013. Today we assess how the changes will affect light sweet crude pricing.”

Thanks ROCKMAN,

I think they more or less said what I was trying to say, albeit with a lot more detail and analysis.

I'm very intrigued as to what the strategy will be for Canadian crudes being exported from the Gulf Coast (I assume they are not affected by the US ban on exports, though that may be a false assumption).

On the whole, I think the unblocking of Cushing (and the Permian Basin) will have a dampening effect on global sweet crude benchmarks, though that must be considered in the light of the overall tightening that we should expect in crude pricing. I.E. despite the unblocking of Cushing/Permian (and the Canadian border?) crude prices may well be higher in the future, just not as high as they would have been if the bottlenecks persisted...

Rock- Rbnergy has some pretty well researched posts. I actually replied to this post (as jwwrightmt). I do think though that he has underestimated the ability of seaborne Gulf shipments to reach the east coast markets. It won't take much of a discount in LLS for shipments from Corpus to other points in the gulf to begin to move up the east coast.

I don't think that LLS will completely disconnect from Brent.

NFE- It doesn't matter if it is illegal to export Canadian crude from the gulf coast. There is way more heavy oil refining capacity on the gulf than will ever be met by Canadian crude. Shipping costs will dictate that Canadian oil on the gulf will be refined not exported.

It is not illegal to export refined products from the gulf coast.

Canadian oil may be exported from the gulf coast but only after it is refined.

If more Canadian oil reaches the gulf it will replace inputs to refineries from other heavy oils like Venezuela and Saudi Arabia.

Thanks for the link to RBN. That was quite informative.

I am not sure about the backing out of heavy crude in the way that you have imagined. The Gulf coast refineries are set up to run heavy sour crude, and have a lot of coking capacity, and I mean a lot. The Permian basin crudes are 38-42 API, very light, even lighter than Brent, and this will cause a few issues in these refineries if run straight. The heavy end of the refinery capacity will be underutilised and to back out all of the heavy crude seems to me unlikley. More likley they might blend the light crude with heavy crude or even atmospheric resid to ensure that they have enough of the heavy end of the barrel to load up the cokers. Otherwise they will have a lot of underutilised capacity and the effective refinery throughput could go DOWN.

carnot-I don't disagree with anything you said in that post maybe I stated what a meant poorly.

I was specifically referring to the thought that Canadian crude will be exported from the gulf coast if it gets that far. My point was that the refiners in the gulf need the heavy oil like the Canadian oil and rather than exporting it they would use it. There is so much heavy demand on the gulf coast that Keystone XL flowing full out with Canadian crude would never get close to surpassing it. It could back out some other heavy imports but not all of them.

The oil without refining capacity on the gulf will soon be the eagle ford, Permian and Bakken oils. Corpus was the first to be oversupplied with light oil and start shipping it out in significant volumes last year. Houston is probably oversupplied at the moment or probably will be very soon.

w - You probably already know this but for others who don't: paper swaps. We don't talk about it much here but it's done all the time. Company A, say a Chinese company, owns Canadian oil. But for a variety of reason can't get it to China but is shipping it to a Gulf Coast refiner. Company B owns some Indonesian oil. So Company A swaps (on paper) ownership of some Canadian oil volume to Company B for some of their oil. There may be some price adjustments as well given grade variations. So China gets to ship that Ind. oil to the homeland and the Ind. company sells the Canadian oil it now owns to a Gulf Coast refiner.

So essentially China was able to "import" its Canadian oil back to China. But the obvious question: why doesn't the Chinese company just sell the oil to the GC refiner and use that money to buy the Ind. oil? Other than saving some transport costs (which is often the prime motive) a real incentive behind such swaps can be ACCESS to the oil production. Assume all the Ind. oil is owned or under contract to third parties: China can't buy what isn't for sale. It's similar to having a “call" or right of first refusal on such production. Not a big deal today but in the past when access to oil/NG was a big issue such calls and ROFR's where very important leverages. When NG supplies got very tight in New England decades ago utilities that had paid for a ROFR satisfied their customers’ demand. Those that didn’t have such ROFR had to curtail deliveries to its customers. For instance it isn't important at the moment but supposedly part of the incentive for China to loan many $billions to Brazil for Deep Water development was China getting the FOFR on a volume of future Bz oil. IOW as long as China paid the then current market price that volume of oil had to be sold to China and no one else...such as the US. Again not a big deal today. But in 5 or 10 years?

The Canadians are not particularly thrilled because the pipeline bottlenecks have moved to the Canadian border and heavy oil is backing up within Canada. Western Canadian Select (WCS) is currently trading at $32 under the price of WTI and $50 under the price of Brent.

It is causing a lot of political problems for Canadian governments, not least of which is because the governments themselves are losing money. Canadian governments collect a higher percentage of oil revenue in the form of taxes and royalties than US governments - Some states collect no severance taxes at all, and the US federal government does not have a Goods & Services Tax on oil companies like the Canadian government. This lost revenue is causing government deficits where they would otherwise be running surpluses.

One oil company CEO calculated the total revenue loss to Canadians of pipeline bottlenecks is currently running about $1,200 per person per year. As a result of its vast oil sands, Canada can produce considerably more oil than it does now, but selling it is a different issue.

Rockman--Let us know what you learn please.

I am no insider but with Seaway practically running through my back yard and my natural nerdy interest in energy I have been doing a fair amount of research on oil flow in my new home state of Texas the last couple years.

I am making some assumptions that may not be correct. If you are selling Texas crude based on light sweet oil prices in Louisiana it seems most likely that you are shipping from Corpus. If that is an incorrect assumption then much of the rest of this comment is probably less relevant to you.

I think that most of the recent roller coaster ride LLS has been experiencing is because traders with lots of money to move markets are trading in local oil price commodities that they think they understand will be affected by the expansion. They are moving these relatively small markets dramatically. They don't understand that capacity from Houston to Louisiana is currently strained and that Seaway actually has little impact on the eastern gulf at the moment.

I read this morning in the WSJ that Seaway is running near pre-expansion levels because the terminals at the end can only take 170,000 barrels per day. Investigation leads me to believe that what actually happened this week was traders got hold of technical info from Enterprise and misinterpreted it. Customers were probably told that we need to slow down what is being delivered to Jones Creek and find other delivery points. At start-up they are probably shipping more light than heavy to test things out. The market for light crude in Houston is saturated so storage at Jones Creek quickly filled up (until the HO-HO reversal comes online this shouldn't significantly affect the actual supply/demand situation in the eastern gulf for light oil). There is lots of demand in Houston still for heavy crude so when Seaway's mix changes to a heavier one storage should no longer be an issue. Also it appears that Enterprise can take oil off in Katy and ship and store much of the surplus light oil at Houston locations other than Jones Creek. So it is likely that the flow down Seaway is actually and will continue to be significantly higher than what the WSJ is reporting that it is or will be.

Coastal shipments could change this but Jones Act vessels are pretty busy already so it is unlikely we will see significant coastal movements of crude from Houston to Louisiana before HO-HO comes online.

The LLS traders will figure this out soon.

Meanwhile Valero and KNOC (who actually have people that understand the physical supply/demand issues) are making a fortune this month loading oil indexed to LLS based prices in Corpus and shipping it to their refineries in Canada. (sweet arbitrage for them)

If Corpus can expand their capacity to load these 330,000 to 500,000 barrel tankers in a reasonable time frame then when the glut of light oil from the Permian and Bakken overwhelm the Gulf's capacity to profitably refine light oil at market prices then most oil from Corpus will flow up the east coast and should eventually be indexed to Brent (though at a 1-5 dollar discount for shipping costs). From a price standpoint Eagle Ford oil is sitting pretty in the world market.

If I were exporting light oil out of Corpus my biggest concern would be with Corpus's ability to load tankers faster and load bigger tankers. That is what will make the biggest difference in realized prices for Eagle Ford shippers.

W – So far I getting mostly no responses from sources. Not unusual for oil traders. A lot of money can be made on just a $.50 slide in prices. And when I do get some sort of an answer I don’t know if I should believe it.

I’m actually barging my Matagorda County oil out of the terminals south Victoria. I can’t say for sure how the Houston to Lake Charles capacity is strained or not. There are lots of barges/push boats along the coast and it’s not a very long run up the Intercoastall Waterway. I think you may be correct about traders making incorrect assumptions. As far as demand in Houston for heavy crude I haven’t heard much about the huge Saudi refinery in Port A except that they expect it to become operational soon. Given the original plan was to ship a lot of Saudi heavy to it. But I’m not sure that will stay the plan if a lot more Canadian rude makes it to the coast. I don’t have any feeling for what the KSA price point might be. Likewise for the leverage to ship (or not) products to the east coast instead of oil.

The overall dynamics are way beyond my capacity to pick t apart. The only hard number I have is how my revenue checks for my Matagorda oil have been bouncing down and then up

The problem at Corpus is the low bridge (a/k/a "Napoleon's Hat"). There are folks who would replace it, see: ftp://ftp.dot.state.tx.us/pub/txdot-info/tpp/ports_waterways/harbor_brid...

The greater problem is the mindset in Corpus. Many don't really think the locals can get the job done, though a few differ (see: http://www.caller.com/news/2011/aug/14/effort-to-replace-harbor-bridge-c...). Hence the activity up South of Victoria referenced in this thread by Rockman. As I recall, they did put one supertanker into the channel there, and it was not easy. They had to remove the radar from the tanker superstructure, and still scraped the bottom going under it.

My guess is that the 'no new taxes' people in Corpus will keep anything from happening for those 20 years of life left to Napoleon's Hat assigned by the CT.

Craig

edit: The other part of the problem is the loading infrastructure. Unless done by the oil companies, that is problematic. The Port was not able to convince the populace of the value of having decent container equipment years ago, and I doubt their resolve has changed in any meaningful way.

Valero has been shipping Eagle Ford oil from Texas to its Quebec refinery. Feedstock costs have been causing heavy losses at the Quebec refinery, and sweet, light Eagle Ford oil is cheaper than sweet, light West African oil. I doubt that the Quebec refinery could handle the heavy, sour oil being shipped from Canada to the US Gulf Coast - the Gulf Coast refineries are much better able to handle that stuff.

It's something of a myth that companies can't export oil from the US. It is true that they need a permit, but permits have become relatively easy to get.

Valero to ship Eagle Ford crude to Quebec plant

600K-800K?

Are you talking about the Gulf Coast project that will bring 700K later this year and 830+K when fully operational?

What about the 450K twinning of Seaway next year?

What about all the small 30-230K projects coming out of the Permian over the next 2 years. While technically not from cushing they are expansions of capacity that allow tons of oil currently flowing into Cushing to be diverted to the gulf rather than sent to Cushing.

Being in Calgary, I can tell you that canadians are really pushing for key stone pipeline. It look like a distant dream to me. But, Chinese interest in Canadian oil and gas industry can be seen from recently acquired NEXEN.

In future, we will be seeing much of Canadian oil and gas flowing to CHINA instead of USA..

I am wondering if more pipelines aren't needed, as Rockman says.

Also, the refineries on the coast were pretty much full the last I looked, so some of the oil being refined on the Gulf Coast has to go elsewhere--either the new oil coming in, or the oil that previously was being refined there. This presumably means more heavy oil for China and other places where there are refineries for heavy oil. Once it is refined there, I would imagine it pretty much stays there. East Coast refineries without "crackers" will still be out of luck, except perhaps that the Bakken oil will have an alternate route to the East Coast (pipeline to the Gulf, then tanker to East Coast refineries). I don't know how this compares with train cost to the East Coast.

gail--A significant portion of the cost of shipping by tanker is the loading and unloading costs. That means the first light oil to move up the east coast will most likely be oil that is currently being shipped in tankers from Corpus to the Northern Gulf coast. Eagle Ford oil could be displaced by Bakken oil in East Texas and Louisiana and instead flow up the east coast to be unloaded there.

Good point!

I agree. Also, in a "they must be watching us" moment, here is an update on Port of Corpus Christi / Harbor Bridge:

http://portofcorpuschristi.com/index.php/94-broadcasts-seacasts/374-new-...

and,

http://portofcorpuschristi.com/

Craig

I have been looking for data confirming a decline in air miles traveled. Anyone able to post a link? Thx!

Can't assure this is the data you're looking for, but this looks quite interesting :

http://www.developpement-durable.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/2013_01_07_AOC_decembre...

The link you provide is for France. I expect the situation in the US is different, because the Euro came into use in 2002, facilitating transportation within the countries with the currency.

Air travel to and from developing countries has no doubt "taken off" in recent years. I haven't looked at that.

So the world situation has a lot of nuances to it.

the first page is for the whole world.

so look at PKT, first page. passenger kilometers traveled are still growing everywhere it seems.

however, transporting cargo (TKF, fret) has declined somewhat globally.

Sorry I didn't look at it closely enough. Thanks for the link!

I see the CR (passenger load factor) has been increasing on a world-wide basis, and is quite a bit higher in North America than elsewhere on the most recent year. North America is only broken out separately for the latest year. Seats offered and passenger freight are both down in North America, and their year change are lower than anywhere else in the world..

http://atwonline.com/airline-finance-data/news/us-airline-passenger-load...

Record load factors are the rule as airlines decrease flights, increase efficiency for large hubs. They are getting better at judging equipment needs, increasing size of aircraft with new gen engines, while limiting the number of flights and scheduling better. Of course, they are also jamming more and more bodies into those aircraft, so that for most folks flying is less comfortable. I once had to spend most of a flight standing up since my knees hit the back of the seat in front, and after take off I could not extend my legs into the aisle.

I think that more and more people are flying strictly for business purposes, and less for leisure. I know that to get a good rate, you have to book months in advance any more as the majors hold back more seats for their business customers. And, flying at the last minute is a good prescription for penury.

Craig

I talk a little about tends in fuel consumption in my latest Our FInite World post, How High Oil Prices Lead to Recession. This is a chart from that post:

This chart shows jet fuel consumed, compared to 1994 (as well as three other fuels). Since Jet fuel use is way down, so it is pretty clear that the miles traveled by jets is down as well.

While I didn't show it in this chart, diesel and gasoline have held up in usage better than practically anything else. The very heavy grades are now increasingly being "cracked" to make transportation fuels. The only exception is very light fractions such as ethane, which comes from natural gas liquids.These are now in higher supply, thanks to the rise of "liquids" production from natural gas,. Ethane's price has recently dropped, because of excess supply relative to manufacturing capacity.

While I have no doubt that total miles traveled by jet has fallen, especially since 2008, is there any data out there as to how much of the reduction in jet fuel consumption is due to airline fuel efficiency due to upgrading of fleets to newer models.

I found this report which provides some interesting data, unfortunately it only goes up to 2008, it might be nice to see a more recent update.

http://ec.europa.eu/transport/modes/air/doc/fuel_report_final.pdf

There is a chart in the report that seems to indicate that fuel efficiency improvements due to technological improvements are close to reaching physical limits... damn laws of physics seem to get us every time!

Oh, and they still seem to be counting on infinite growth, of course back in 2008 no one could have foreseen that a day would come when growth might slow down a bit /sarc

I expect with jets, most fuel improvements have come through retirements of older short-distance jets (as well as flying with fewer empty seats). It is my understanding that the jets that were retired were less fuel efficient. At the same time, airports in some smaller cities were closed. New more fuel efficient jets take a long time to get into service. Boeing's new Dreamliner, which is supposed to be 20% more fuel efficient than other jets, was started in 2003. Boeing has over 800 orders, and only 50 in service so far. As you no doubt have heard, the 50 in service have been grounded for battery problems. The major reason for the bigger batteries needed was the fact that more functions were being made electric, to save fuel.

I do have some charts for autos, though, and they seem to say that the vast majority of gasoline fuel savings have been from driving less. On the chart below, the miles traveled is from Department of Transportation estimates (here and here). The gap between the "gasoline" (red) and the "miles traveled" (blue) lines represents the increase in car fuel economy. It is clear from the chart below that the vast majority of the gasoline savings is from fewer miles driven, rather than from better mileage. There seems to be evidence that the gap is widening at the end, a hopeful sign.

I show distillate on the above chart as well. This is primarily diesel fuel, but includes a little home heating oil as well. Its use tends to be more volatile--respond more quickly to ups and downs in the economy.

Over the period 1994 to 2012, both seem to be pretty closely correlated with the number of people with jobs in the economy. The (r2 for each one is about .92).

These are from my large stack of things that I have run across, that need to be written up as posts.

The transportation sector accounts for over a quarter of total world energy use, and the proportion has increased since 1973. Cars, trucks and air transport use most of the transport energy; in the European Union, road transport represents 82% and air transport represents 14% of the trans¬port energy. Transport of people both for work and for leisure increase dramatically as people become wealthier. A flight from England to Mallorca was a big thing and was very costly in the 1960s; now it is almost like catching a bus, and would be a lot more so if it weren’t for all the security measures. Unless there is a major shift away from current patterns of energy use, world transportation energy use is expected to grow at 2% per year, with energy use reaching 80% above 2002 levels by 2030 (Garden Earth, Gunnar Rundgren 2012).

Air transport is still increasing and increasing quicker than energy efficiency saves fuel. The efficiency gains in the air have not been impressive and take a long time to reach out. I travel in many countries and frequently travel in planes that are fifty years old!

USA Today has this available on its website:

http://travel.usatoday.com/flights/airline-capacity-map.htm

I have tracked it for several years. Generally speaking, airlines are looking to consolidate, maximizing seat utilization. Watch for trends in shorter trips, as these tend to have a higher cost per passenger.

Watching for trends, or setting trends? In watching, we see what mass marketing and propaganda can accomplish in the short term. Were we to turn rather to setting trends, we would see an evolution, or more precisely a re-evolution, in train transportation. Short flights are less efficient for many reasons; we should see an evolution from short flights to train routes (probably elevated - maybe monorail, or similar concept - with light freight and passengers traveling at higher speeds above heavy trains the will continue to serve on presently existing tracks, and modified from diesel electric to pure electric transmission), and later, as air travel becomes impossibly expensive, high speed elevated train travel. The hope would be that it would be city center to city center, though through the 'kulge' (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kludge) process of economic evolution it may wind up that existing airports will become "trainports" as well.

The real problem is the extent of sunk capital involved in the cheap-oil economy we have in place, and the lack of replacement capital, compounded by the extent to which those with vested interests in the present model control that capital.

Craig

THX to you all!

Does CPI urban include fuel, food and rent ?

Common Misconceptions about the Consumer Price Index: Questions and Answers

This blog post has 3 charts of YOY change in Energy CPI. The data goes back to 1957 so I'm puzzled why EIA aren't presenting the full historical perspective on this matter. The BLS data shows energy as a % of wages even higher 30 years ago, too. I couldn't find any charts covering this matter, no doubt Hamilton has examined it exhaustively somewhere though.

Isn't the real problem that Social Security, CPI Index Funds and most COLA formulae tend to use the core CPI? Problem, that is, if you are on fixed income and having budgetary difficulties.

Craig

I understand CPI-Urban does include fuel, food, and rent. There is another version that I didn't use that does not.

There is a fair amount of controversy as to whether the statistics, as computed, understate the effect of inflation. For example, the calculations they way they are done assume that if the price of a preferred type of goods (beef) moves up, an alternate type of goods (chicken) will be produced, so that the rise in the price of beef has less effect than it would otherwise. It also attempts to figure out how much quality improvement is included in new products, such as cars, refrigerators, and computers. (Thus, if the price goes up, it isn't inflation, it is because you are buying a better product.) Shadow Stats shows alternative inflation amounts, which are higher.

The government has great incentive to understate reported inflation rates, to the extent it can, for several reasons:

1. The higher the inflation rate, the higher the increase in benefits for Social Security recipients.

2. Reported real GDP numbers are better if inflation rates are lower.

3. Calculated efficiency gains are higher, if inflation rates are lower.

Gail, there was a reader comment on TOD a few days ago that maybe the CPI inflation value was understated by 50%. Do you think it could be off by that much?

If they are talking about a difference between a 2% reported and a 3% actual inflation rate, I would think a difference of that size is quite possible, and in fact, quite likely. Efficiency gains are quite small, so an error of this size tends to fairly significantly wipe them out.

There is another reason the government has an incentive to under-report true inflation:

Government debt is liquidated an increasing amount these days via direct purchase of debt bonds by central banks, aka, "money printing", or "quantitative easing", or "debt monetization", or "keeping deflation at bay at all costs". This dilutes the money supply and, all else being equal, results in inflation. Inflation is a transfer of wealth from savers to debtors. By artificially stating inflation too low, the effects of this money printing are hidden, so that retirees and other savers are duped into keeping their money invested in the system, happy with their 3% return, even though the cost to live is actually rising faster than 3%. Naturally, the rational response to a lower-than-bond-return rise in commodities prices would be for savers to dump all their bonds and instead put their savings into the commodities markets. However, by introducing volatility into the markets, savers can be scared out of these kinds of moves (that would bring the whole system crashing down), and be convinced to remain in the "stable" bond market, even though it delivers a negative real return and ultimately, is the greatest ponzi scheme in the history of the world and has zero fundamental value, because all debt (bonds) is now insolvent and without further economic growth, cannot be serviced.

It's interesting to ponder about what the yard stick should be to measure inflation against. For example, one could say that oil price has increased 8% per year over the last 10 years, whereas inflation was only 3% per year (I am just guessing at those figures, I don't have them off the top of my head right now). Therefore, oil price increased 5% more than inflation. Well, how does one define the baseline inflation metric? Since everything in the economy ultimately comes back to energy, then shouldn't the true measure to which inflation should be compared be the price of a Joule of energy, for example oil? So what "Joule" of energy should should be used? Gasoline? Electricity? Natural gas? Food?

It seems the government's CPI figures are wildly understated, but at the same time I'm not so sure I accept the Shadowstats ones either. I am starting to develop my own inflation statistics that more accurately represent how the real cost to live an equivalent lifestyle since 1950 has changed.

Interestingly, from beginning to look at the data, it seems that coal and electricity have maintained their absolute price over the last 100 years or so. Yes, that's right -- a kW-hr of electricity now costs the same in ABSOLUTE DOLLARS (around 10 cents) as it did around 100 years ago! Electricity is now WAY cheaper than it used to be.

The one caveat with respect to commodity prices is that someone, in fact, has to be able to afford to pay the high prices for the commodities. This seems to at best lead to very volatile commodity prices.

The price of land should theoretically rise, too, like commodities.

As commodity and land prices (and energy prices in general) rise, I think what you end up with is a situation which is fundamentally unstable, because while the population needs the land and commodities, it can't really afford them. The book Secular Cycles by Peter Turchin and Sergey Nefedov looks at what happens takes in past civilizations which ended in collapse. In the book, they talk about four stages of a "secular cycle", which includes collapse. This is my summary of their four stages (over about a 300 year period), as shown in my post, 2013: Beginning of Long-Term Recession?

It seems to me that volatility in commodities is one of the things that marks the transition from phase 2 to phase 3. High land prices and serious tax problems also mark the transition from Phase 2 to Phase 3.

How a person "properly" measures inflation is really an open question. For example, part of the reason that a single wage-earner could support a family in the 1950s is because homes were much smaller then, and no one worried much about fancy landscaping, or letting kids play outside with other kids for a few hours at a time. Now there is the expectation that mom will drive children to play outings with other children, and that homes will be larger and fancier. How do you take into account a changing way of life?

Might be drifting a little OT with this, but as the military is so energy intensive and intertwined in the energy/government picture...what does this graph look like if you take out the increases in "Defense" spending since 2001 - just the increase, not the baseline around 500 bill/yr (700B/yr with debt interest): http://gailtheactuary.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/us-government-spending...

This supposed deliberate underestimation of inflation tastes too much like a conspiracy theory to me. I'd like to see evidence put forward for its actual existence, rather than having it deduced because its results are supposedly favourable to the powers that be.

It is correct to say that the CPI underestimates the change in the cost of living, but that is very different from saying it's manipulated. Rather, society changes so that the cost of participating in it rises over time, particularly for those at the bottom of the income scale. The CPI, which measures changes in the cost of a fixed basket of goods and services, doesn't take account of that. Some examples are:

(a) This year's standard model from Detroit Inc is a little more expensive than last year's. Some of its standard features, however, were optional extras last year. After accounting for the quality difference, the car component in the CPI doesn't rise in price.

(b) This year's standard desktop computer from Silicon Valley Inc is the same price as last year's. It has at least 50% more RAM, though, as well as more storage on the hard drive and better sound & video cards. After accounting for the quality difference, the computer component of the CPI goes down.

(c) Building a new house in outer suburbia (on a block you already own) is more expensive than last year, because the the builders have all put an extra room in their plans, increasing the size of the dwelling. People continue to buy them, however, because they are assumed to be a good investment over the long term. Because of the extra room, however, the price rise doesn't put up the house purchase component of the CPI. In fact, the price on a per square basis decreases, so it sends the CPI down.

(d) Building a new house in outer suburbia means doing it an extra kilometre or so further out than last year, so you'll have to drive further to get anywhere and burn more petrol doing it. This doesn't figure in the CPI at all.

Note that none of these things result from manipulation of the index. Instead, they just serve to point out the difference between a price index and a cost of living index. I could also add how some expenses have become practical necessities these days (e.g. home computers, mobile phones) or conveniences that, while rare when my generation was young, are now practically inconceivable for many to go without (e.g. dishwashers, air).

Finally, the impact of the factors I set out above is far more powerful on people at the lower end of the income scale for two reasons:

(a) People at the bottom of the income scale don't usually buy according to a trade-off of price vs quality (as the economic textbooks would predict), but instead they buy the cheapest version available. If the cheapest version available is going up in price because of quality increases, their costs go up. People further up the income scale, and who are choosing a product on the predicted price vs quality trade-off, can afford to buy the same version this year as last year, even though it is standard this year but came as "standard + optional extras" last year.

(b) When you look at the goods and services which are decreasing in price (or at least, because of quality improvements, decreasing in their contribution to the CPI) and compare them to the ones that are increasing, you will find that for the most part, the essentials of life are increasing at a faster rate than discretionary expenditure. Therefore, the basket of goods and services that low income people consume will have a higher CPI than the basket for the community as a whole and especially higher than the basket for people towards (though not necessarily at) the top of the scale.

Price indexes exist in their current form for good reasons. They help break the rise in income over time into rises in the "standard of living" on the one hand and price levels on the other (though not perfectly - see my example above re driving distances). They do not, however, do anything to account for how the cost of living changes in a different way from the price levels. Many changes in the "standard of living" are not optional and are reflected in the cost of living. Certainly, governments take advantage of the inadequacy of the CPI as a cost of living measure, but that is another matter. Another matter entirely.

The data doesn't seem to agree with that idea, though.

Take a look at census data on average annual expenditures broken out by income quintile for 1989 vs. 2011. Food is the most basic "essential of life" category, but it's been dropping as a share of expenses, even for the poorest 20%:

- 1989: 18.2%

- 2011: 16.1%

Incidentally, that's also pretty conclusive evidence that the shadowstats guy is blowing smoke to sell subscriptions to his data -- he's claiming purchasing power has fallen by 50% since the mid-80s, but if that were true, we would expect food to take up more of people's incomes, not less.

(Relatedly, MIT's Billion Prices Project is a separate measure of inflation, but gives very similar results to CPI.)

Another possibility is that other things like housing, transportation, medical, schooling, taxes, etc have risen faster than food and has, to a certain extent, crowded food out. All part of the hedonic adjustment from steak to ground beef. Both keep you alive but one costs less than the other.

Remember that we're talking about:

- the lowest-income 20%

- a claimed 50% drop in purchasing power

- a demonstrated 12% drop in food expenditure share

For all of those to be true, 1989's poorest could have spent only 44% as much on their food and still eaten as well as today's poorest. By suggesting hedonics accounts for that, you're suggesting that 1989's poorest had an enormous amount of luxury built into their food choices.

That's quite a strong statement; is there evidence to support it?

The data you provided easily supported the 12% drop in the food expenditure share of income which is what I was referring too. Housing alone ate twice the drop in food.

As for the shadowstats 50% decline in purchasing power, I'm guessing this means that as income doubled during this time period prices would have quadrupled? That does seem excessive however the bottom 20% seems to be struggling more than I remember in 1989 and seems to require more assistance both public and private. In my area, the demand on the food pantries has risen significantly even with the expansion of the SNAP program.

Yes, percentages sum to 100, so of course reductions in the share spent on food will appear somewhere else.

What's important is that food is one of the least-discretionary categories for poor people -- you can decide to live in a smaller apartment or share it with more people, but there's a biological limit to how much less food you can eat. Accordingly, an effective 50% drop in income for the already-poorest cannot reasonably result in a 50% reduction in food expenditures, meaning that the share of expenses devoted to food should increase.

By contrast, we see the share of expenses devoted to food decrease, even for the poorest. As a result, we can be reasonably confident that they have not suffered a massive decrease in purchasing power, and hence we can reject the hypothesis that inflation is as high as shadowstats suggests.

Agreed, I think you make a very valid point.

Null Hypothesis, putting money in a CD at our local credit union gets one about 1% interest with a two year term. With the CPI at almost twice that it is defintely a transfer of wealth from the saver to the debtor. Now if the real inflation is double the government stats (e.g. 3 to 6%), then we are losing out even more.

Per US stats: US CPI Data

gail......you hit the biggest ones but here are a few more

4. Tax brackets are indexed to inflation... the lower inflation is the more people pay higher tax rates.

5. Tax exemptions are indexed to inflation so higher inflation leads to higher income tax deductions.

6. CSRS and FERS pensions are indexed to inflation so lower inflation leads to less pay to federal retirees.

wright1bby:

Your comments elsewhere were quite good. I have a few questions about this post, though:

about 4: it seems to make the unwarranted assumption that wages still go up when there is low inflation. Given our experience, the opposite is true.

about 5: there is a difference between exemptions and deductions. Even if exemptions are indexed, deductions are not. And, with the AMT not being indexed (for most of its life within the tax code), they actually drop. Not sure what your point is in any event.

about 6: so is Social Security. So what? If the price of oil is increasingly controlled by extraction cost, fewer dollars still will not reduce the ultimate cost of oil to below replacement, at least without significant deflation in both prices and wages - that is to say a revaluation of the dollar vis-a-vis labor.

Overall, I am not sure what your point was. Maybe I am having a slow day? For most folks the problem with the cost of living indexing is that it does not cover the actual increase during times of inflation, largely because the 'official' rates are gamed so heavily.

Picking nits with any of the big 10 listed by Gail is not, IMO, a profitable enterprise. The overall points she made are that: oil price impacts prices of many things. There seems to be a strong correlation between increases in oil price and recession or economic downturn. And, the cost of oil recovery is going up so the price of oil will not drop during those economic downturns. Hence the economic impact of high oil prices can reasonably be expected to be somewhat greater. And therefore, the more oil production costs do increase, the more impact they will have on the economy. Not really rocket science; it is more like reasoning by deduction. I think she made the points clearly - a rarity in recent commentary on the subject from other sources.

Craig

I agree with you. with respect to 4, 5, and 6.

I think what Zaphod is saying is that if people are on average earning less and contributing less, the new brackets may not get total tax collections up to the old level they were, before layoffs and wage cuts.

This is not really the point though. If we compare expected tax collections with an estimated 2% inflation rate with expected tax collection with an estimated 3% inflation rate, collections will be higher with the estimated 2% inflation rate.

That would be true if you are saying that the indexing is at 2% vs 3% and the actual income increase is, say 1%. In that case, you would be indexing lower taxes. If on the other hand, income increases at more than 3% then taxes would increase (in nominal dollars) due to higher actual income and you would be indexing higher taxes. The determinate is whether actual wages change at a rate larger or smaller than the index rate. And, again, in the likely case that index rate is less than actual rate, AMT would raise effective rates higher for even more taxpayers.

Stated differently, it is more obvious: In cases where nominal wages increase at a rate above index, tax collections increase. In cases where nominal wages increase at a rate below index, tax collections decrease.

Craig

Does anyone really believe this? Planned obsolescence is a more likely hypothesis, IMO. One recalls the "light bulb conspiracy" of the 1920's. http://conspiracy.wikia.com/wiki/Light_bulb_conspiracy

A not scientific, but realistic account is one of washing machines and clothes dryers. Recently I have noted mine last about 3 to 5 years (depending, interestingly enough, on how long the warranty is), whereas those I purchased in the 1960s were still in frequent use 30 years later, and with few if any service calls. My grandmother's refrigerator (had the coils on top) lasted 50 years; our has a life of about 10.

While I will admit that my fridge is a bit 'neater' than hers (coils hidden, water and ice through the door), the basic function is the same, and hers did it just as well as mine. Also, the ice maker breaks down right after the warranty runs out! In every one I have had to date! Without fail! So much for "better!" The better part is propaganda for planned obsolescence.

/end rant

Craig

Thanks, Gail. What we're discussing, in a nutshell, is the inevitable limits-to growth/overshoot nexus. Substituting eroei-inferior sources of energy and credit/debt for finite resources, and the chorus of rationalizations we're seeing for a continued massive depletion rate of real capital; all symptoms of the endgame for industrial population explosion. "Rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic" may be a crude clich`, but that's exactly what we're doing.

Industrial civilization is the mother of all ponzi schemes, nothing more.

How long do you think this situation can continue for? Japan has been an economic disaster zone for two decades now, in the U.S. the S&P 500 has is back to where it was 13 years ago.

Japan, treading water, so to speak, has occured during a period when global economic growth was continuing, able to skim off resources with the aid of nations still a bit higher on the overall decline curve. Think intrest payments on their US Treasury bonds, continuing exports, etc. Where would (will) Japan be without these things. Where will they be as global resource ELM progresses. They may already be winning the race to the bottom, a possible advantage going forward, and they have other advantages such as a legacy of social/racial/cultural cohesion which will certainly be advantageous while weathering the storms of contraction, being the first, as Kunstler suggests, to return to a world made by hand. It won't be easy, but perhaps easier for Japan than for many.

On a personal level, being an early adopter of austerity, resilence, and a certain level of self-sufficiency helped my family through a time when we saw many folks in our area lose everything they had been working for. Most of these folks, who were on a similar socio-economic level, are desperatly attempting to claw their way back to where they were, pre-2008, still investing in the wrong things, still insisting that society do the same. We are using this "inertial period" to wean ourselves from any longage of expectations we may have had in the past.

Those societies that leverage what remains of a still massive endowment of resources to develop a much lower level of reliance on said resources, paying sustainability forward, IMO, will also be able to leverage what may be only a slight advantage as other less forward-looking societies crash and burn. Of course, what remains of more short-sighted cultures won't be content to stand by and admire the success of others. It's the paradox of global overshoot.

The 20 or so years that Japan has been coming to terms with it's resource limits is just a moment in time compared to the global contraction which is the net legacy of industrialism. We, collectivly, are using up the planet. There's nowhere, and no way, to hide from that for long.

High oil prices will be a relatively short-lived problem.

It seems like it is an issue of how far a system can be stretched until it breaks. This is hard to tell, but there are a lot of telltale signs. It seems quite possible that a significant decline could start in the next year or two.

THe financial problems of the United States, most of Europe and Japan are more and more coming to the fore. It is hard to believe that the US dollar can continue to be the reserve currency forever. ASPO-USA ran a post on this subject recently, that was interesting. Why Peak Oil Threatens the International Monetary System. I don't know whether it will be the continuation of the dollar as reserve currency, or simply something that causes interest rates to rise (despite all of the "money printing" that is going on today). It seems like the "advanced countries are very vulnerable--it would only take slide of confidence to set things off. THe result may not be too different from the collapse of the Former Soviet Union in 1991, but affecting the US, EU, and perhaps Japan.

The less developed countries may band together and continue onward for a while longer, without the pesky oil demands of the (formerly) high income countries.

So I read Bernstein Research (I don't know who they are) says it costs $92 per barrel to bring new oil to market now and is rising at least 10% per year. Any comments? Appreciated from all, especially those who celebrate new Bakken production highs.

I don't have all the answers on this one. I know the number of drilling rigs is down since mid-year, but supposedly efficiency is up. I know that there is a lag for fracking, so some of the new production may represent fracking of previously drilled wells.

North Dakota data is showing that November oil production is lower than October, but this is supposedly because of snow in November.

I am wondering if we need to wait a little longer to see how this falls out. It takes a while for changes to feed through the system.