Why is US Oil Consumption Lower? Better Gasoline Mileage?

Posted by Gail the Actuary on February 6, 2013 - 10:57am

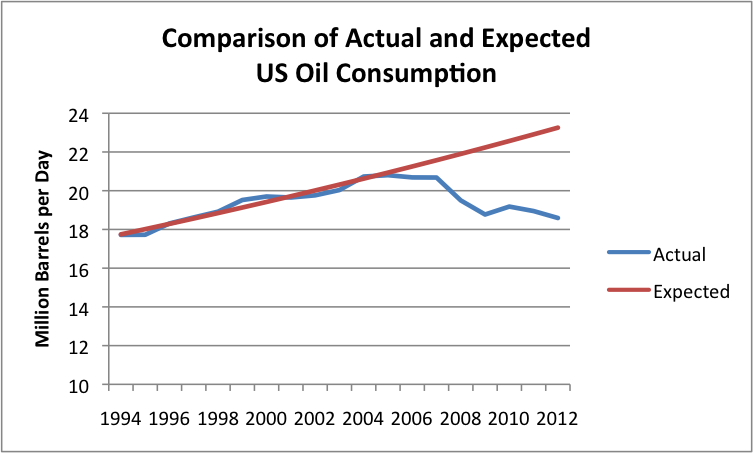

United States oil consumption in 2012 will be about 4.7 million barrels a day, or 20%, lower than it would have been, if the pre-2005 trend in oil consumption growth of 1.5% per year had continued. This drop in consumption is no doubt related to a rise in oil prices starting about 2004.

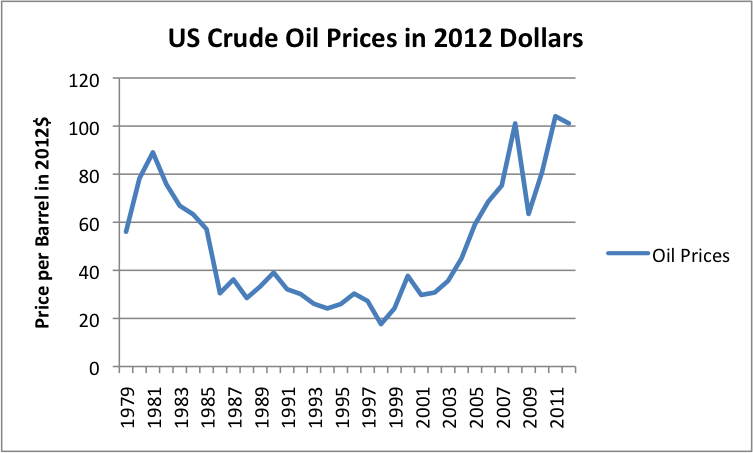

Oil prices started rising rapidly in the 2004-2005 period (Figure 2, below). They reached a peak in 2008, then dipped in 2009. They are now again at a very high level.

Given the timing of the drop off in oil consumption, we would expect that most of the drop off would be the result of “demand destruction” as the result of high oil prices. In this post, we will see more specifically where this decline in consumption occurred.

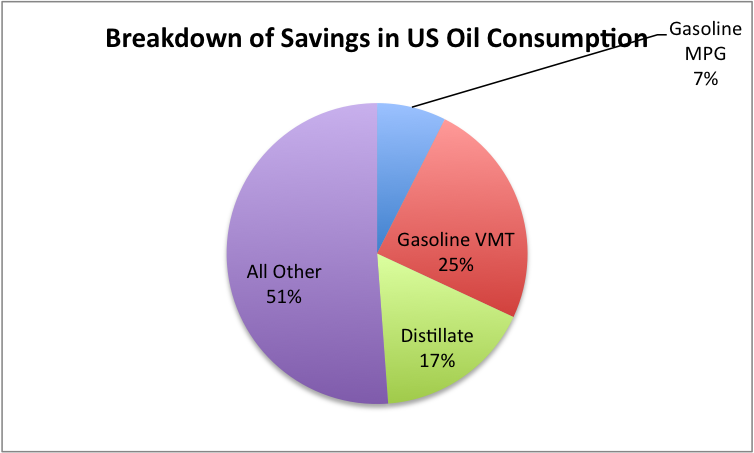

A small part of the decline in oil consumption comes from improved gasoline mileage. My analysis incidates that about 7% of the reduction in oil use was due to better automobile mileage. The amount of savings related to improved gasoline mileage between 2004 and 2012 brought gasoline consumption down by about 347,000 barrels a day. The annual savings due to mileage improvements would be about one-eighth of this, or 43,000 barrels a day.

Apart from improved gasoline mileage, the vast majority of the savings seem to come from (1) continued shrinkage of US industrial activity, (2) a reduction in vehicle miles traveled, and (3) recessionary influences (likely related to high oil prices) on businesses, leading to job layoffs and less fuel use.

Gasoline Savings from Better MPG, Fewer Miles Traveled

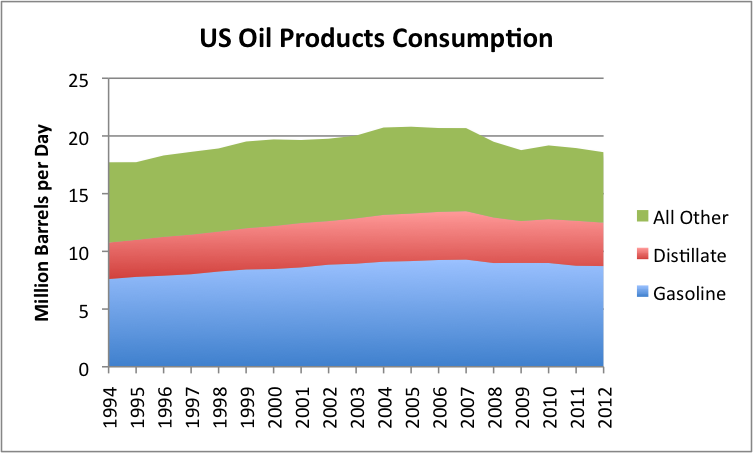

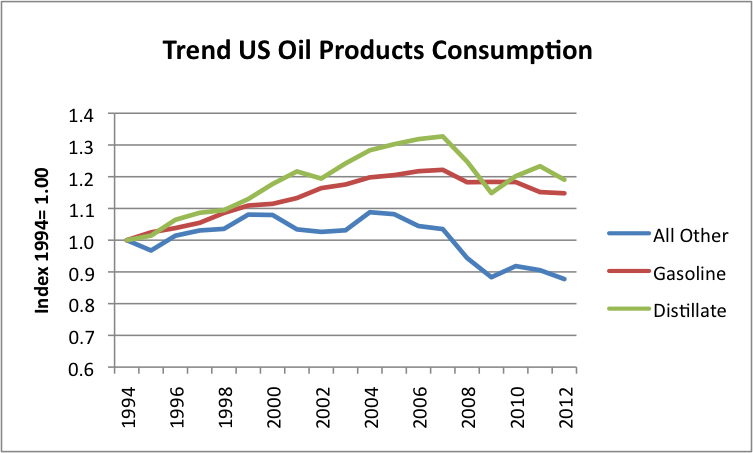

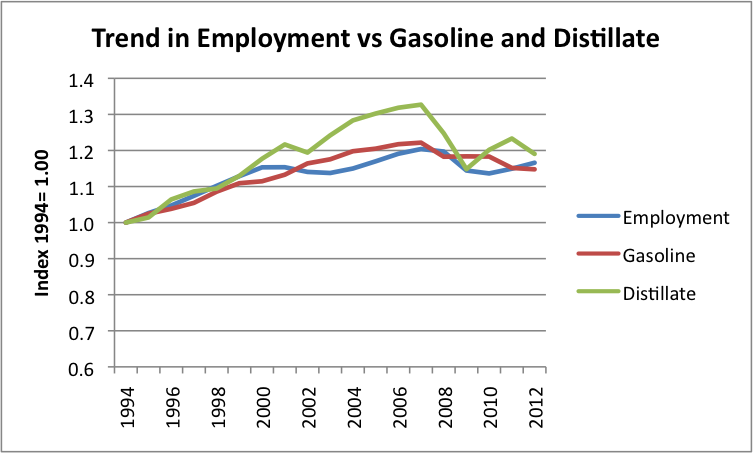

Figure 3 below shows how the consumption of gasoline, distillate, and “All Other” oil products has changed since 1994. (Distillate is used mostly as diesel fuel, but some of it is used for industrial purposes, and some it is used for home heating.)

Of the three product groupings shown, gasoline1 consumption is the flattest. Under “normal” circumstances, we would expect gasoline consumption to continue to rise, along with oil products in general, as shown in Figure 1 at the top of the post.

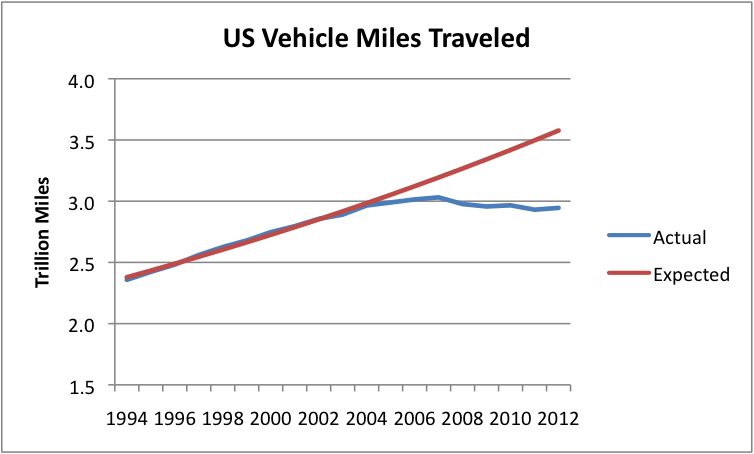

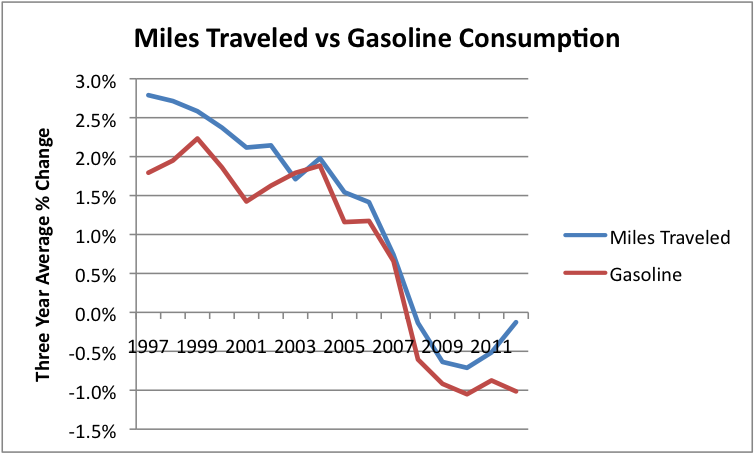

The amount of gasoline consumed reflects at least two different influences (1) the number of miles traveled, and (2) savings due to more fuel efficient cars. Based on data compiled by the US Department of Transportation, vehicle miles traveled (VMT) were rising by 2.2% per year prior to 2004, then suddenly flattened (Figure 4, below) about the time oil prices started to rise significantly.

The drop in vehicle miles traveled greatly affects gasoline sales. If vehicle miles traveled had continued to rise as quickly as in the early period, we would expect automobile mileage to be 21% higher than my current projection for the full year 2012, and gasoline use would be equivalently higher.

How do changes in gasoline sales track with changes in VMT? Figure 5, below, shows that they track fairly closely. Annual changes in gasoline consumption are a little below changes in VMT (averaging about 0.4% below VMT).

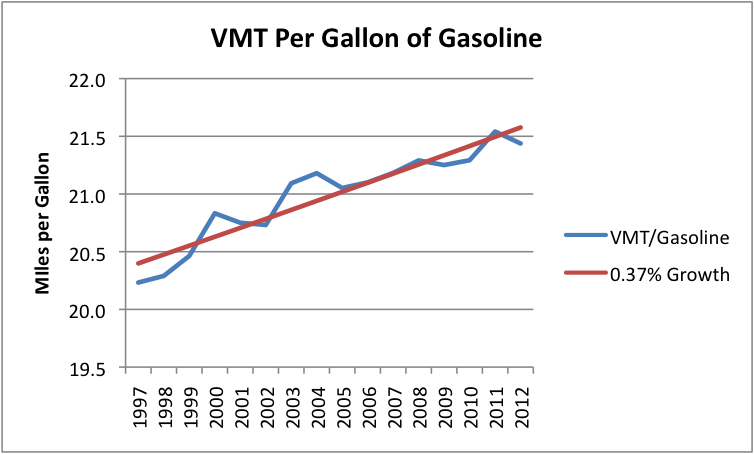

It is also possible to calculate implied VMT per gallon of gasoline (Figure 6, below). This is somewhat of an apples to oranges comparison because VMT includes travel by vehicles using fuels other than gasoline (usually diesel, but occasionally natural gas or electricity). As a result, the calculated mileage in Figure 6 is higher than the actual average MPG for gasoline powered vehicles. If the proportion of gasoline powered vehicles in the mix stays fairly constant, the annual percentage change should still be accurate, though.

If we apply the 2004 rate of fuel usage (or MPG) to 2012 VMT, we find that the improvement in fuel mileage between 2004 and 2012 reduced fuel usage by 347 thousand barrels a day over the eight year period, which is equivalent to a reduction of about 43 thousand barrels a day, per year.

The total reduction in gasoline use between 2004 and 2012, relative to what would have been expected, (based on the trend line in Figure 1, assuming the mix of products each retain their 2004 proportions) is about 1.49 million barrels a day. Thus, this calculation implies that about 23% of gasoline savings is from better mileage; the other 77% is from driving fewer miles.

One point of interest is the fact that US population has recently been growing by 1% per year. Because of the growing population, a person would expect VMT to grow by at least 1% per year, unless per capita miles driven is shrinking. Since 2004, vehicle miles traveled have been growing less rapidly than population growth. As a result, mileage per person has been shrinking, recently by a little over 1% per year. Prior to 2004, vehicle miles traveled were growing at 2.2% a year while population was growing at 1.1% per year, implying that per capita miles traveled were increasing by 1.1% per year.

How do vehicle miles per person go from increasing to decreasing? There are a couple of possible ways. One is by a reduction in the number of drivers; the other is by decreasing the number of miles driven for individual drivers. My friends who are automobile insurance actuaries tell me that at least part of the change recently is that fewer young people are driving. This is not too surprising–young people today have very high unemployment rates, so they are less able to afford the cost of a car.

Fuel Savings for Distillate and for Other Oil Products

Figure 7, below, shows the trend in fuel consumption since 1994 for the same fuels as shown in Figure 3. It is clear from Figure 7 that gasoline and distillate consumption have followed fairly similar patterns. It is the “All Other” category that has shrunk markedly.

At least part of the reason the “All Other” portion is shrinking is the fact that the All Other category includes quite a bit of oil products for industrial use, and the amount oil products used by the industrial sector shrank by 7.9%, comparing 2011 to 1994.

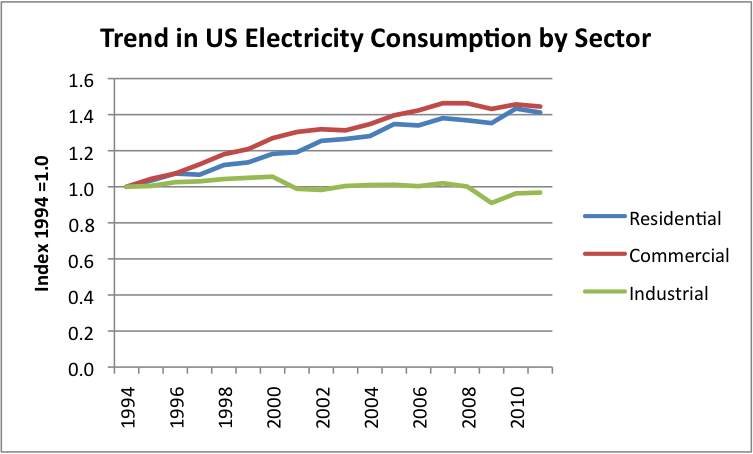

We can also look at the use of other energy products by sector, to see additional evidence that the Industrial Sector is shrinking, or at least, not growing nearly as much as the other sectors are growing. For example, if we look at electricity use by sector, residential use is up by 41% since 1994, commercial use (office and stores) is up by 44% since 1994, while industrial use is down by 3%.

Also, between 1994 and 2011, use of natural gas by the industrial sector declined by 8.5% further suggesting that the industrial sector that is shrinking. One factor in this shrinkage is likely increased competition from China, once they joined the World Trade Organization in December 2001.

Of course, part of the reason for the lower growth in oil products use by All Other could be greater industrial efficiency. Industrial users, and users such a big agriculture and aviation, are in a position to see ways to reduce oil use quickly. Such approaches would include “no till” farming (often substituting oil-based herbicides for oil-based tilling) and cutting back on unprofitable airline routes, saving fuel by grounding underutilized jets and laying off workers.

Part of the reduction in All Other use, too, could be that at the high oil prices available recently, refiners can make more greater profits by ”cracking” and refining the heavy portion of oil, rather than sell it as products such as asphalt or residual fuel oil. Because of this, refiners are making less of the “All Other” products, and more Distillate and Gasoline. Users of heavy products are forced find substitutes, such as diesel or coal or concrete.

Another point of interest is the fact that the trend in gasoline and in distillate consumption both roughly follow the trend in the number of jobs available in the US economy.

There is a theoretical reason why gasoline consumption might rise and fall with employment. People who have jobs can afford to buy cars and drive them. People who don’t, often can’t afford to drive.

Distillate use tends to bounce around more, as if businesses (who tend to use diesel fuel) are more influenced by economic conditions than individual drivers driving gasoline powered cars. The overall trend still seems to follow employment, though. This would seem to suggest that if less fuel is used by vehicles, this is often accompianied by fewer workers–either fewer drivers for trucks, or fewer workers making the goods carried in the trucks. There may be gradual mileage efficiency gains, but in the short run, the big fuel savings come from operational changes that lead to using fewer vehicles and also fewer workers.

Summary of Where Oil Savings Comes From

As stated at the beginning of the post, United States oil consumption is about 4.7 million barrels a day lower in 2012 than would have been expected based on pre-2005 patterns. The way that this savings breaks out by product grouping is as follows:

Decreased gasoline usage due to improved gasoline mileage amounts to 7% of the total, decreased gasoline usage because of fewer miles traveled amounts to 25% of the total, and a decrease in distillate use amounts to 17% of the savings. The majority of the decrease, 51%, comes from a decrease in the “All Other” category, which is most closely related to a decrease in industrialization.

The way the calculation is made is as follows: The trend line forecast of 2012 consumption of oil products shown in Figure 1 is distributed to product based on the product’s share of 2004 US oil consumption. The year 2004 is used as a baseline because it approximately represents the situation before the big rise in oil prices took place. The savings is then the difference between (1) these forecasts of consumption by product and (2) my estimates of 2012 actual consumption by product. The latter estimates should be fairly “solid,” because they are based on actual consumption through October.

Going forward, fuel efficiency changes are likely to play a larger role in fuel savings, because CAFE (Corporate Average Fuel Efficiency) Standards have been unchanged for about 20 years. For model years 2012 to 2016, they are again increasing, so auto makers are again making more of an effort to improve mileage.

Actual fuel efficiency gains in the next several years for the US fleet of cars will depend partly on the mileage improvements incorporated by manufacturers, and partly on how many of these more efficient (but also more expensive) cars are purchased. I have recently forecast that we will be entering another very-long recession in 2013. The recently announced decline in US GDP in the fourth quarter of 2012 is another indication in this direction. In a recession, it will be difficult to sell as many of the new fuel-efficient vehicles.

Another factor that is likely to be important for future actual vehicle mileage is the condition of roads. Mileage estimates are based on having good paved roads. If local governments find their budgets stretched thin, road maintenance may not get proper funding. We may even see more gravel roads, if asphalt is increasingly unavailable, and concrete is too expensive.

Note:

[1] Gasoline as used in this analysis includes any ethanol that is blended in. This has been an increasing percentage over time, and now is typically 10% by volume. The addition of ethanol tends to keep mileage down because ethanol only gets about two-thirds as many miles per gallon as gasoline. I have not attempted to adjust for this. The mileage gain would be somewhat better, if ethanol had not been added to the gasoline. An increase in the ethanol blend to 15% have been approved. As this is phased in, it will also tend to depress mileage gains.

This post originally appeared on Our Finite World.

An excellent analysis as usual by Gail.

However except for this note:

Yes numerous data sources indicate that young people are not getting cars, driving and even not getting drivers licenses at all. So how are they getting anywhere? They are moving back to Transit oriented cities and places, taking the Megabus, and increasingly taking Green public transit. According to a recent USPIRG study of young people and transit 16% are taking more Green public transit for Environmental reasons!

It is not just due to not having a job.

My own daughter and her friends have moved to the city where she has not even needed to use the Zipcar membership I got her. All of her cousins except for one understand the need to reduce driving out of concern for greenhouse emissions and Climate Change which they all accept as reality, even the right wing cousin interested in the military.

I believe public transit has been increasing about 5% per year which has a disproportionate impact on saving oil. Intercity bus riders increased 27% last year!

This is why as James Kunstler has long advocated, Rail and Green Transit are key to mobility in the future. Even Bill McKibben in his latest speech to the Vermont legislature said there should be no more car expansion and there needs to be restoration of passenger service in Vermont.

It is a pity that Auto Addicted Atlanta rejected the recent proposed tax hike to pay for

restoring Green Transit in the Railroad Hub of the South. When you live in these areas it is understandable that Auto Addiction seems immutable like a force of nature. Unlike the NYC Metro area which already has the top 3 populous cities with the lowest car ownership per capita: New York, Newark, NJ and Jersey City, NJ.

But there are still 233,000 miles of Rail as in Atlanta all over the USA waiting to be restored to passenger service.

Another factor is the high cost of auto insurance, especially for anyone under 25, and most especially for males under 18. These costs, combined with real enforcement of insurance requirements and stagnant or falling real wages make it hard for an employed young person, much less an unemployed young person, to be able to run a car without parental subsidy. My own daughter, a librarian, got a job straight out of graduate school over six years ago and has exactly the same salary she had in 2006. She is in better financial shape than most of her friends from high school.

The contribution of better fuel economy can be expected to grow quite quickly. My niece's husband bought a 2011 full size pickup to replace his 2005 one, and was very pleasantly surprised to find that his real-life fuel economy was 19 miles per gallon. His old pickup, the same size, got about 13 miles per gallon. That's 32% drop fuel usage. Interestingly, his old pickup never did as well as the EPA rating (16 combined), but the new one does better (also 16 combined).

I have an adult daughter who lives in Boston and does not have a car. She found an apartment she could share practically next door to where she works, so she has no need to commute. Grocery stores and most other frequent shopping needs are nearby as well. Occasionally, she uses public transit or a taxi. There are even a few times she catches a ride with a friend. (She prefers not to drive in city traffic.)

My husband and I have followed somewhat this same model as well. We live on the edge of the campus where my husband works. Before we moved here (while the children were still in high school), we lived within a short walking distance of the school, so that our children could walk (even though there were no sidewalks). Everyone else's children rode the school bus, or the parents drove them to school.

I am not convinced that the Zipcar model is financially viable. Zipcar has continually lost money on the idea. A company has to have seven day a week rentals for its cars, or very much higher rates, to make a profit. Zipcar ends up being close by, but doesn't rent enough during the week.

Public transit is a separate issue. It seems to work where population is dense. It is less clear that it can be made to work where it is not.

From my experience with my children and their friends, I think that there are many reasons other than financial that their cohort is driving less.

Living in Boulder Colorado many of my children's friends are from super-affluent families, and lots of them went to private colleges, including Ivy League, on the east coast. Their families could afford cars for their kids without a second thought. But mostly this group has chosen to live in dense city cores where car ownership is pretty much more hassle than it is worth. So they almost all get by with transit, Chinatown buses, foot, and bike and maybe some car-share. I think the biggest difference is cultural, in that this group is rejecting the suburban/auto lifestyle, in favor of a mainly pedestrian urban lifestyle. Clearly cultural changes can be temporary and faddish, so I don't think anyone can really say if their distaste for automobile dependence will continue as they get older, have children and demanding jobs, etc. But I know that using laptops and smart phones on buses and subways is a normal part of life for this generation, so without self-driving cars they mostly consider driving time as wasted time, since they cannot be working and goofing off on electronics while driving.

I also disagree with Gail's comments about economics of car-sharing. The link posted above says that Zipcar is expected to be between break-even and $3 Million profit this quarter, despite massive costs for system expansion. Here is Boulder we have Ego Carshare which is a non-profit that has no resources for running at a loss, users must pay the full costs or shut down. The economics of many vehicles are overwhelmingly in favor of the car share model. I can use the car share pickup trucks for about $4 hour + 30 cents/mile, gasoline included. Even if I used the pickup truck every week of the year, I would only spend about $500 per year, versus the estimated $9000 per year cost of the cheapest pickup truck available (http://www.edmunds.com/car-reviews/lowest-cost-to-own.html). So with car share I can get the utility of a truck while spending better than an order of magnitude less. Aside from the hokey marketing fake masculinity aspect, there is really no reason for non-rural and non-construction people to own trucks. Car share and smart phones work together beautifully, just like urban bike share programs do too (GPS tells you nearest available vehicle, gives directions, phone reserves and bills car/bike share usage,etc.). This system makes way too much economic sense, compared to the dumb-ass model of buying a $20K personal vehicle that spends much more than half the time sitting unused but incurring very expensive depreciation. Car and bike sharing are growing at effectively geometric growth rates globally, so the financial problems of one particular company in one particular market (ie.,Zipcar which is growing itself at about 15% per year) cannot reasonably be used to predict world-wide results (see the graph in http://www.carsharing.net/library/UCD-ITS-RR-06-22.pdf). The financial analysts at Hertz and Avis certainly believe that car share will continue to grow, since they are making big investments in carshare, including spending $500 Million to purchase Zipcar (if they questioned the financial model would they invest half a billion?).

Thanks for the additional information on car-sharing. The only one I had run across was Zipcar.

I expect the car-shaing model will need to use older, less expensive cars to keep cost down, since ultimately, that is what most users would normally be driving.

The social as well as the financial and environmental aspects of car and bike sharing or mass transportation seem to be important to the younger generations.

Well all the answers I see from US of A

For my children here in the - well they are put off by insurance ( well I am as I FUND it )

18 yrs Girl full license 1 yrs no claims on a Ford KA 1.3 ( 38 mpg imperial of course) 1800GBP full comp. - third party fire and theft - 1760GBP - over here the reason given is third party claims for whiplash amongst other things.

I her college most actually are on their parents insurance - not a lot saved I might add as they insure on the highest risk driver.

For my Son , a Honda CBR 125 14BHP 90MPG imperial ( kool! still can reach 80 mph on motorway) 17 with full license ( restricted to 33HP - got in before the laws changed yet again here ) 600GBP third party F&T.

His friends? most are learning to drive a car like he is - again insurance is high > upto 3000GBP on a 1.0ltr car of 1200GBP value with 1000GBP excess ( daughters is 400GBP ) .

Does make you wonder why but when you see the poor bus services - two changes to town - 5 miles away , and three back ( I kid you not ) and the cost , to sit on a smelly often late bus ??

Right , if you're going to and from London , theres good routes but even the train costs are rubbish compared to buying a chinese 125 or moped and running that !

Across country ? forget it the infrastructure is geared to going to London and back - and you wont be buying or renting much there on a min wage job , even pooling .....

Well that's what its like from this side of the pond where I live . your mileage may vary

Forbin

In Victoria, Australia, the youngin's need 120hrs on learner plates before they can apply for a full license. That's a lot of parenting time, not to mention cost of all that unnecessary "driving around". My prefect daughter (that's prefect, not perfect... though that as well! :)) - and it seems the vast majority of her friends, male and female, don't seem to have a burning desire to drive.

Fine by me, BTW.

Yet another anecdote. Our family downsized to one car four years ago. (Got rid of the minivan, just have a 2004 Prius.) We got two electric bikes in addition to regular bikes, and outfitted all our kids' bikes appropriate to ride in the city. (Lights, fenders, etc. We ended up with eight bikes in the garage where the van used to be.) We also got a subscription to CityCarShare, a non-profit competitor to ZipCar here in San Francisco. We find we don't use it much. We live up a huge hill, so in general though my husband and I bicycle nearly daily, the kids when teenagers preferred to take the bus.

My oldest is now 22, still doesn't have a driver's license. He's out of school with his own apartment and a full time job. To get to work, he bikes to Caltrain, takes his bike on the train. Middle child also has no driver's license and is at a college that doesn't allow freshman to have cars on campus. She can come home on vacation from her college by train. Youngest (15) is hot to get her license. We'll see. The substantial money we've saved on cars and insurance has gone into college tuition.

It is good that young people are moving to the cities and taking mass transit. That will leave more room in the suburbs for the 1.5 million people that will immigrate to the country each year.

Immigrants typically move to the inner city areas first, and tend to take mass transit because that is what they did in their home countries. The suburbs, I think, are just going to become rather empty.

Demographer Alan Ehrenhalt argues convincingly in his book The Great Inversion that FiniteQuantity is right: There is a new and widespread pattern at work in US cities whereby both the grown up children of the previous generation of the 'flight to the suburbs' set and an important number of retired suburbanites themselves are moving back to gentrifying inner city areas. And that they are being replaced in suburban and exurban locals by the poor and and new arrivals.

This is the reversal of the postwar pattern that RMG refers to, hence: The Great Inversion.

It's a very carefully constructed argument and uses data form all kinds of cities from the sunbelt to the rustbelt, not just the urbanists favourites of Manhattan, SF, or Portland.

It's observable all over the OECD, we call it here in Auckland the 'flight to the centre'. It goes hand in hand with the fall-off in driving; in other words many of those that can afford to rearrange their spatial conditions to reduce their driving are doing it. As usual the poor and new immigrants in fit with what's available. Poverty is now suburban, areas which suffer from disconnection by distance to employment and other services, poor urban form [cul de sacs etc], poor Transit provision; auto-dependency.

The really interesting question is: Is this simply a response to rising costs of car use or is it the 'spirit of the times', the zeitgiest, a fashion?

My contention is that it is both however the later is the more powerful force. And is as unstoppable as the abandonment of the inner cities and the invention of auto-dependant suburbia was in the post-war era.

The word 'urban' used to be code for any number of things to be avoided by polite society; decay, race, poverty. It now is increasingly associated with; sophistication, desirable real estate, success.

Worth a read:

http://www.amazon.com/Great-Inversion-Future-American-City/dp/0307272745

.

That's interesting. I downloaded the book to my iPad so I can read it.

The author points to the example of Paris, which is quite different from American cities, and deliberately so. The French government deliberately encouraged the wealthy to live in the inner city areas of Paris, and they pushed the poor and the immigrants into the suburbs because that was the only place where people who were not wealthy could afford to live.

But that required the French to spend a lot of money on the Metro and similar urban services. US governments did quite the reverse and subsidized the building of freeways and rampant suburban development, while starving the inner cities of money.

He gives the example of Vancouver as a city which has developed quite differently than US cities, and I can relate to that since I was born in Vancouver and still visit there often. However, Vancouver was the only major city in North America which did not build any urban freeways, and driving there is quite a challenge. Gasoline is very expensive because of the multiple taxes on it. OTOH, the SkyTrain is a very advanced, albeit expensive piece of transportation technology, and definitely something that encourages living in the inner city area.

I don't think most Americans realized the forces that drove their movement to the suburbs were not random, and were not as important in other countries. The biggest factor was cheap gasoline, and that was compounded by the rampant construction of freeways. In cities that did not build freeways, Vancouver being the only major one in North America, commuting in from the suburbs to the inner city was a great deal less fun. The movement to the suburbs in other North American cities is coming to an end, mostly because of high gasoline prices and the fact that governments can no longer afford to maintain and expand the freeways, and the re-population of the inner cities is starting to become a major factor.

Yes Vancouver is the great model, Paris less so. Paris is wonderful, except where it isn't. Les Banlieu: Multi story slums for the disaffected mostly from France's old colonies. Too easily ignored by the ruling elite, hence the recourse to rioting in order to get noticed. An example of Corbusian modernism at its most miserable (great architect; terrible urban designer, just like Wright). Paris is a great Transit city though and they are now expanding this place saving resource out to the blighted Banlieu.

Back to North America; you can drive from Mexico all the way up the west coast and the first time you will have to stop at a traffic light is Vancouver. But I would disagree strongly with the idea that the Skytrain is expensive, what?; interstates don't cost anything? And how about opex? The driverless electric Skytrain is hugely cost effective and model for all the world, especially good in places like Canada (&NZ, Norway) with a huge hydroelectric resource. A great way to displace fossil fuel dependency.

What you really mean is that the auto-highway complex successfully structured the way we (taxpayers) fund infrastructure to make roads appear free and god given and right but Transit as commie, unaffordable, wasteful, and therefore highly contested and all but impossible to build. Insane, but it is the same all through the anglophone world.

The Skytrain and other good urbanist policies in Vancouver is one reason for that city's increasing success. The contrast with the more auto-dependant cities is only going to widen as this century unfolds. The Pacific Northwest looks a better bet to me both climate wise and in terms of spatial organisation and movement options than the entire sunbelt going forward.

When I said the Vancouver SkyTrain is expensive, I was looking at it from the perspective of the cost of the Calgary CTrain, which I rode to work for years.

The Calgary LRT system set a new standard for cost-effectiveness - it managed to run the equivalent of a 16-lane freeway through the middle of downtown without a lot of fuss or bother using the center two lanes of one narrow downtown street. Buses, taxis, and police cars used the outer two lanes. And it was essentially powered by wind turbines on a wind farm in Southern Alberta. See http://www.calgarytransit.com/pdf/calgary_ctrain_effective_capital_utili...

Yes, the Vancouver SkyTrain was inexpensive relative to the cost of urban freeways, but the Calgary CTrain verged on being ridiculously inexpensive. It carried passengers for a cost of about 27 cents per trip.

That's undoubtedly a factor, but I think Patrick is right in pointing out that there's a shift in attitudes away from driving.

Among my peer group (mostly in their 30s), driving is widely seen as a chore and a waste of time, not a leisure activity or source of freedom. Several households I know have no interest in owning a car, despite having plenty of money -- they prefer to live centrally and walk or take transit. It's not a universal attitude, of course, but for many of us the celebration of car culture on display in 60s and 70s media looks not just archaic, but unfathomable.

As a result, I would expect car use to significantly erode in North America in the coming decades, regardless of oil prices. Factor in persistently high gas prices, better efficiency standards, and improving hybrid/EV technology, and I expect gasoline consumption to be in terminal decline even without any oil shortages.

It's obvious that expensive fuel and high unemployment will make it hard to live in car-dependent suburbs.

To me it is obvious that with infinite immigration and birth rates still above replacement level (a lot of that due to the higher birth rates of immigrant mothers) that today's American suburbs are tomorrow's American cities. So you can have your house in the suburbs and eventually it will be a house in a city. In California the suburbs have all filled in wall to wall and now the city councils scour the area looking for commercial buildings that can be torn down and replaced by condos or taller commercial buildings to support the population growth from immigrants (California has had a negative outflow with respect to the rest of the US for most of three decades).

And while it would seem likely that immigration would stop at some point if the price of oil skyrockets and brings the economy to it's knees, that might not ever be the case. Immigration is a very sacred cow and not a peep, not a single peep was heard about stopping it - not even stopping illegal immigration - when unemployment was consistently at 10%. In fact, CEOs and economists are always praising immigration and while not always advocating an overall increase, are always advocating an increase in the number of college educated immigrants. And the silence with regard to an infinite immigration is not just at CEO and economist gatherings. Even Peak Oilers speak very little of it.

Immigration from Mexico is pretty much zero right now, due to unemployment in the US, and higher growth in Mexico.

And, US birth rates are below replacement, and dropping.

"Immigration from Mexico is pretty much zero right now, due to unemployment in the US, and higher growth in Mexico."

I assume you are referring only to illegal immigration from Mexico, as this

http://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/immigration-statisti...

shows that in 2011 Mexico sent more people legally to the US than any other country. I don't think that they would have gone from the highest amount to 0 in one year. I don't believe there are any people reporting how many illegals they are hiring or how many illegals they are renting to, so any claim that there are less illegals (let alone that there are virtually none) coming from Mexico is unverifiable. Because there is such a tremendous disparity in standard of living between the two countries, there is still a tremendous incentive to come illegally to the US, even if someone has a job in Mexico. The other thing is that they are in the process of legalizing millions of illegals. At some point employers and the rich will want a fresh group of illegals as they will work for less than legals work for, and under more severe conditions and with more disregard from the employer.

"And, US birth rates are below replacement, and dropping."

If you look at this graph, you will see that it has dropped before, and subsequently risen. So I think it is too early to declare a negative population growth rate from internal births. In fact, between 1960 and 2010, the lowest fertility rate was in 1976. The graph only shows data to 2010, but from that it can be seen that only one year since 1976 (2007) has had a higher fertility rate than 2010. So if it is dropping in the last two years, the 36 year long term trend is up.

https://www.google.com/publicdata/explore?ds=d5bncppjof8f9_&met_y=sp_dyn...

What baffles me is that I always see a significant percentage of our population growth (up something like 110 million since 1970) as being from internal births. And yet that graph shows a 2.1 or lower fertility rate for over 30 years. Presumably that is from births being more than deaths through that period. But even with the past low fertility rates, the US is projecting births to be more than deaths for the 45 years from 2015 through 2060, although they will become closer as time goes on. They are also projecting a population increase during that period of a 100 million people. But I guess all will be fine if the 100 million new people take the bus.

http://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2012/summaryt...

The population growth from legal immigration continues at a pace of over 1 million a year as shown in the PDF above.

It's easy to cut fuel costs. For instance, buy a Prius C. If that doesn't do it, buy a Nissan Leaf.

Actually, the unemployed will find it much easier to live in the suburbs, because the cost of living is much lower. Of course, that only works if the suburbs allow zoning for small, cheap apartments. If not, that may force people to where those exist, like dense cities.

If someone is unemployed, I think they are better off living in the suburbs. With no money they will need to board for free from a relative or friend, and there is more room in houses than in small, cheap apartments.

I think that the 2004 video "End of Suburbia" was generally very accurate. Link to trailer:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qHr8OzaloLM

Except it's completely unrealistic.

Really.

Electric vehicles (partial and 100%) work just fine for transportation. Electric rail works just fine for freight.

Nick. No.

Perhaps you have heard of the London Underground, or all the other successful passenger rail systems in the world. I guess you are American (my apologies if not), if you will concede that NYC is part of the union you might have ridden the subway there? I think we can agree that it works and only carries human self-loading freight, otherwise known as passengers and is powered by electricity.

I may be wrong but what it seems you are trying argue in your comments here is that the highly dispersed world of he American suburbs can remain unchanged and viable through the agency of the electric car. Maybe. But I wouldn't count on it. Especially as we are already seeing a decline in enthusiasm for this spatial order, not critical yet but the trend is clear. Those that do remain viable are likely to be much more like earlier suburbs built more densely around Transit nodes.

I agree that electricity is the coming energy system but this side of a huge revolution in battery technology tethered systems will always have huge advantages. No need to waste most of the energy dragging that heavy battery around.

Remember the first suburbs were in fact built around the train and remain pretty good places to live in those cities that didn't destroy them by ramming freeways through and running down or pulling out the Transit system.

But I guess it's a question of what we can afford to do; change all our vehicles and power them or move to less auto dependant places... We'll probably do a bit of both.... But I wouldn't be aiming to retire on the value of a big house in a distant 'burb; may not be all that many takers in a decade.

Patrick,

I like electric rail - it's safer, and I can read while I ride - I use it daily. I like dense, walkable urban neighborhoods - that's where I live.

But, I recognize that it's much more expensive than exurban living.

The average new car in the US costs $30k. The average US car gets 21 MPG. Partial EVs (hybrids and plugins) and pure EVs range from $19k to $33k, and cost much less to operate. So, there is no life-cycle cost penalty to move to EVs, and the additional upfront cost is very, very small compared to the premium for urban housing.

I hope that rail and Transit-Oriented Development becomes more popular, and that it gets built. But to suggest that PO will *force* the end of the suburbs is highly unrealistic.

Nick you're just doing the selective math that every generation of Americans since the 50s have been taught. Sprawl is the most wasteful, and therefore expensive, social order yet devised, and was certainly only possible because of cheap liquid fuel. Not only directly but also because cheap oil provided the excess easy capital for the OECD [especially the anglophone countries] to expand in this crazy way. Not to mention giving us the mad faith in limitless growth to borrow against.

No sadly PO is not going to get us new transit focussed euro cities, because we've blown the money and then some, living like teenages on that last summer for a few decades. What will happen is that the most auto-dependant and unfixably sprawly [+ water scarce and aircon hungry] cities are going to do it tough. And those happy places that are already denser and better connected outside of the private car will fair better [depending on climate vulnerabilities too].

End of the suburbs? No, although some will go like Detroit's inner city did. This is the point; the blight is reversing: It is survival of the fittest for places, where fittest of course means; 'the best fit'. Those places that best fit the post-cheap oil new economy will be the most successful.

The really interesting question is where are this era's Detroits? Can the obvious solar opportunity save Phoenix and ABQ? Or will their exurbs go back to desert. And how will it go? Will it be Katrina and Sandy events and just a failure to rebuild afterwards [and Fukushima]. Or will it be more financial storms with people just walking away from negative equity...?Fascinating.

The middle of your continent looks likely to be doing it tough for water and with heat, balanced by the current hydrocarbon boom, and the entire UK has an energy crisis that they don't seem to be admitting.....

I've used the "Sixth Sense" metaphor. In the Sixth Sense movie, many ghosts don't know they are dead, and they only see what they want to see. IMO, for most Americans in the 'burbs, our auto-centric, suburban way of life is dead, but most of us don't know it yet, and we only see what we want to see.

just doing the selective math

Patrick,

No offense, but you're not doing the math at all. EVs are perfectly affordable, and wind and solar are affordable (and getting cheap), scalable, high E-ROI, etc.

Again, what's the math behind your intuition that electric transportation won't work?

t this side of a huge revolution in battery technology tethered systems will always have huge advantages. No need to waste most of the energy dragging that heavy battery around.

Actually, it takes very little energy to drag batteries around. The main reason weight is important for vehicles is the energy used to accelerate the mass, which is wasted when one brakes. Regenerative braking, enabled by those batteries, solves that problem.

That's why hybrid electric cars reverse the classic ICE pattern of improved mileage on the highway, and get better mileage at low speeds: aerodynamics become more important, and air friction is lower at lower speeds.

No, you are unrealistic. Electric vehicles are expensive and available in very low volumes and the range is poor and they need at least 8 hours to recharge off a regular charger. Electric rail ? Sounds very good to me. EV's are ok for short commuter trips, but don't look for EV's to replace heavy trucks or other heavy transportation equipment,and if you want to tow a heavy trailer then the EV's range again a problem.

Keep in mind the above is based on current capabilities and production of electric vehicles. Like I said, with a crust concentration of 0.005 parts per million, lithium isn't a widely available resource in large volumes. The barrier to adoption of EV's is cheap, widely available batteries.

Of course, the flip side of declining liquids consumption in OECD countries is increasing consumption in developing countries, led by China. The annual Brent price increased at 17%/year from 2002 to 2011, with one year over year decline in 2009. Over this time frame, the Chindia (China + India) region's consumption increased at 6.1%/year, from 7.6 mbpd in 2002 to 13.2 mbpd in 2011 (BP). Chindia's Net Imports (CNI) increased even faster, going up at 9.6%year, from 3.5 mbpd in 2002 to 8.3 mbpd in 2011.

Link to, and excerpt from, a prior post, with graphics:

http://www.theoildrum.com/node/9795#comment-943202

I agree that this is what is happening to the oil. It is going to countries like China and India, who can make better use of it, while we increasingly go into debt.

There is a myth that if US energy efficiency raises auto fuel efficiency sufficiently, the oil will just be left in the ground, for our children. In fact, world oil supply is constrained. We will use 100% of what is pulled out of the ground. Less demand may mean a little lower oil price, but not necessarily less oil produced for the world as a whole. (Of course, if price drops too low, there will be a big drop in production, as in 2008.) In any event, the oil will be used, quite likely by some one in China or India, who can leverage its use better than we can.

A couple of related posts: Energy Leveraging: An Explanation for China's Success and the World's Unemployment

Why world coal consumption keeps rising; What economists missed

For any commodity there are supply demand curves, both for production and consumption.

If people in the US use less oil, then reduced demand will drop global prices, which will spur consumption at other locations, but also provide less incentive for "producers" to extract more oil from the ground (nobody actually produces oil, of course). So whether US energy efficiency will actually reduce total global oil consumption depends on the shape of the global consumer and "producer" price elasticity curves.

But there is no doubt at all that increased US energy efficiency will reduce energy imports (and thereby improve the trade deficit/balance of payments), improve air quality, save consumers' money, and help develop the efficient technologies required to address both climate change and fossil fuel depletion.

I have never seen anyone espouse the simplistic view quoted above, and would be curious to see a link to anyone making such a silly claim. Clearly individual policies can either speed or delay oil extraction, for example allowing East Coast off-shore oil drilling clearly speeds extraction/depletion, just as the moratorium slows it. The policy position of slowing US oil production wherever possible makes economic and environmental sense, without reference to any silly belief that the oil will "just be left in the ground".

For these reasons, I personally support continued restrictions on East Coast off-shore, Keystone pipeline, ANWR, fracking, etc.. I expect that most of those fuels will eventually be burnt, but delay allows and incentivizes the development of societal change, renewables and efficiency while "Drill, Baby, Drill" does the opposite and sells more SUVs instead.

I agree that from an individual country's point of view, there are reasons for reducing oil consumption, including improving balance of payments. This is a major reason why efficiency improvements are so popular.

Indirect effects are not taken into account in economic models. We know that in practice, world effects are very different from individual country effects. In my view, anything that acts to increase world trade will increase total world emissions, even if the effect on the home country is beneficial. I am sure you have seen how world emissions have increased in recent years, after the Kyoto Protocol was signed in 1997. (See my article Climate Change: The Standard Fixes Don't Work.)

You may not have heard such a simplistic quote, but the view seems to be quite popular among people who are concerned about oil limits. Of course, King Abdullla has made a comment about leaving Saudi oil in the ground for Saudi children.

The comment seems to be made quite often in response to Oil Drum articles, for example, in response to this article. I know in talking with some ASPO-USA members, this is the motivation for buying a Prius, or taking some other oil-saving action. Of course, if the person saves money by the oil saving action, some of the money previously spent on oil will likely be spent on something else, which may also use oil. For example, using the money saved on a vacation.

Normalized liquids consumption for (2005) Top 33 Net Oil Exporters, China, India and the US, from 2002 to 2011 (2002 consumption = 100%, BP data), versus annual Brent crude oil prices (in red):

I think that it is likely that these consumption trends will more or less continue.

...until they can't.

Yeah, it's clear that the US is going in the right direction, and that China and India are digging themselves into oil-import holes.

I would be interested in knowing the impact, if any, of the growth of internet sales on fuel consumption. I think this was debated at some point on TOD but wonder if anyone has any numbers on this.

It seems like it is more efficient for one UPS truck with 100 boxes to take an optimized route to deliver to 100 residences rather than each of those residences to drive to pickup each of those boxes. One key question, however, is whether that actually cuts back on shopping. Maybe most people continue to shop at physical locations with the same regularity while also buying online.

Another issue is that in another era (maybe it still exists in places like New York), when I was a child, it was common to call the grocery store with a grocery list and have the store deliver. No doubt this exists in some places now but it not common. This also seems like a more efficient and certainly more hassle free way to shop. I currently use this kind of service here in Colorado from what is called Door to Door Organics where they deliver once a week.

Back in the 1950s, it was perfectly possible for a family in a small town to be a one-car family (or even a zero-car family). Everything was within walking distance, so children could walk or bicycle to school. Milk was delivered several times a week. Groceries were delivered, if a person called and asked. Clothes often came from a catalog. Furniture came from the store downtown, which delivered.

We are making small steps back in this direction with, as you note, some deliveries of groceries, and some purchases through Amazon. I know I am going to physical book stores less, and I think others are too, judging from the number of book stores that are closing their doors. But my guess is that this the change we have made so far is just small inroads.

I think that one thing that holds up going back to the way things were is the physical layout. Homes are now built on large lots on cul-de-sac streets that make it hard to get anywhere within reasonable walking distance, and make the connecting streets terribly busy. Businesses in the center of small towns have been replaced by stores selling handicrafts and other non-necessities, while grocery stores and Walmart have moved out to the edge of town, making them much harder to walk to. Grocery stores now are huge. In years back, there were small stores on the corners in the city, where a person could walk and purchase the basics. (There may still be, in some places.) Now most people have to drive to a megastore, because the (many fewer) megastores are not nearby.

Agreed that physical layout is a major contributor to US auto dependence.

What is interesting to me is to watch the incremental changes in physical layout that mostly seem to be moving in the other direction. Exurban property has lost much more value than core urban property (http://crosscut.com/2011/08/31/real-estate/21246/Sick-suburbs-expiring-e...). All over the US, developers are adding density to existing urban cores (whenever regulations allow it), and profiting from high demand. Most of the urban re-development that I see is mixed-use, with retail on ground floors and office/residential above. So much of the "sprawl" physical layout of the US is densifying in place, while extreme ex-urban sprawl is becoming either devalued or de-populated. Plus transit-oriented development focused around transit service is booming everywhere that transit exists.

Agreed that every transit mode has a minimum density for economic viability. But there is positive feedback when transit development encourages more dense transit-oriented development, which encourages more transit use, which encourages more TOD, etc.,etc.

The reduced auto dependence and increased transit usage among young age cohorts means that political support for transit investment will only grow as the auto-dependent older generation passes from the scene. My experience with co-workers who got a free transit pass was that the first transit usage was a big roadblock that many never crossed, but that those who used transit once often eventually made transit a normal part of their lives. How many US citizens have never used a bus or subway? So my guess is that a cohort that grew up using transit will continue to use it at some level throughout their lives, unlike people who grew up with auto-dependence as an unthinking and automatic response.

I think it would help if people can get rid of some transportation habits that are very wasteful. For example, if you need to drive to the shop, try making one large shopping trip per week and not every day (some people do that). If you have a shop nearby, try walking there (a bag on wheels is extremely practical). You get exercise and use the local shops which is always good.

Never drive to the gym! If you need to exercise, run around the house 10 times or in the woods or wherever - get some manuals and lift in your garage - or just tidy and clean the house thoroughly (I mean scrubbing) - the exercise in this is great!

Consider getting a tablet and stop buying physical books and newspapers, think of the paper you save and transportation savings. Ofc this isnt good for book stores and sort of assumes that technology and services can exist for a very long time (lets assume that). You wont have to fill your house with books then either - its a more minimalistic approach to reading, not for everyones liking, but the benefits are great (less bookshelves to dust). The same can be said for music and movies. I just went to the movies with my wife and kids and the total price (we used public transit at least) was close to $100 including 2 tickets bus/tram (family ticket), 4 movie tickets, snacks. Most likely I could have bought that movie on a DVD in 1 months time for $15 tops and $10 for some snacks. Ofc if everyone did this the movie theatre would go bust but its really rather silly today to use all this energy and money to get to some place to watch a movie when it can be just as cosy at home (and you can pause the movie and go to the loo). :)

Its clear that a lot of the services offered today is really only possible with the extremely cheap energy we have had (and still have to some degree), although we all know this will change soon. I am under the impression that this change is somewhat good as we need to rethink how we use energy and build our infrastructure to be more walkable or made for public transit.

These dudes seem to concur with your opinion on UPS vs. individuals driving to a store to p/u their stuff:

http://www.cmu.edu/news/archive/2009/March/march3_onlineshopping.shtml

Not sure if riding a bike to a store to p/u would be best of both worlds, guess it depends how optimized Fedex's loads are compared to the store's...

Desert

Yes, absolutely true. One truck delivering to 100 homes is much more efficient than 100 homeowners driving to one place. The problem is the orders aren't concurrent, i.e, orders come in from time to time not all at once.

The three month average Net Petroleum Imports peaked in March of 2007 at 13,089,000 barrels per day. They reached almost that three month average in November of 07 and again in October of 08. Since then the three month average of Net Imported Products have fallen by almost 5 million barrels per day.

Since then US production has risen by about 1.8 mb/d. That would put US consumption down by about 3 million barrels per day. However the US Monthly Energy Review says "Total Products Delivered" (consumption) is down by just over two million barrels per day since the average of 2007.

Using the Monthly Energy Review's figures, US consumption of petroleum products is down at just about 10 percent from the average for 2007 to the average for 2012. That is all products including propane, jet fuel, heating oil and everything else. It is my opinion that the greatest part of that is demand destruction due to high prices. Some of it, a small part, is due to better gas mileage from new cars on the road.

Monthly Net Imports of Petroleum Products, 3 Month Average in KB/d. The last data point is Feb. 1st 2013.

Ron P.

We are in agreement then.

Gail, we seem to agree on most things. ;-)

Ron P.

I came to similar conclusions -- that most of the decline in US oil consumption was due to the recession, not to greater efficiency -- in my investigation of this question back in September: http://www.getreallist.com/has-vehicle-efficiency-really-curbed-u-s-oil-...

Ah, but the claims you show in your article aren't that vehicle MPG was the cause of declining consumption - the claims are mostly about overall efficiency of fuel use (Yergin notwithstanding - as we know, he'll say anything). As Gail pointed out, declines in oil consumption have come more from non-transportation uses.

Sure, MPG hasn't risen much. But, vehicle miles travelled hasn't fallen much, and that decline can be explained by other factors besides the recession. We know for sure that young people with jobs are deciding not to buy cars - their VMT is down by 20%. Other factors include shifts to carpooling, transit, and online shopping.

The bottom line: the meme that declining oil consumption is a bad thing is unrealistic.

We need to kick our addiction to oil, and that will be a good thing.

However you slice it, be it MPG or something else, it's clear enough that efficiency gains played a small role in the decline of US oil consumption. Shifting transportation modes from private autos to mass transit and carpooling, and shopping online rather than in person, are recessionary effects because they're cheaper than driving. What Gail calls "deindustrialization" can also be interpreted as a response to the recession.

The industrialization occurred when production was moved to India and China. You can see it in the U.S or here in Finland. China (and India) has cheap electricity from coal, cheap and abundant labor, and lax environmental standards. The environmental standards are really strict in Finland. Many towns here that have derelict smokestack industries, industry just went right down here or what's left is heavily automated and has a minimum of employees.

it's clear enough that efficiency gains played a small role in the decline of US oil consumption.

Well, no, it's not. First, it appears that industrial/commercial efficiencies were more important than transportation - the "other" that Gail discusses. Gail is wrong to assume "deindustrialization".

2nd, VMT has fallen to some extent because of changing preferences: young people, even if they're employed, are driving less, in part because they recognize the external costs (CO2 emissions) of driving. People are shopping online because they like it better.

3rd, substitutes like mass transit and carpooling may be considered slightly inferior (and therefore 2nd choices when gas is cheap), but that's far from TEOTWAWKI.

But what is "demand destruction"?

If a homeowner insulates, or switches from fuel oil to an electric heat pump, they're far better off. If a shopper decides to buy something on Amazon or Peapod instead of driving to the store, they're probably better off than even before prices rose.

"demand destruction" has such a negative sound.

Most of demand destruction has to do with people losing jobs--the people working in the store that is now losing out to Amazon, for example. Jobs seem to move to countries where costs are cheaper--wages lower, more coal use, etc. I would call this demand destruction pretty negative.

Most of demand destruction has to do with people losing jobs

I don't think you've done the research and analysis to support that. That's just an assumption. I'd say most "demand destruction" has to do with low value energy use being eliminated(by insulation, for instance), and low cost greater efficiency.

Jobs seem to move to countries where costs are cheaper

No, most job loss in areas like manufacturing have to do with automation and greater labor productivity.

In the short run, people changing jobs is painful (like from a local store to Amazon). But, in the long run, it's the basis of prosperity.

Finally, unemployment is a very bad thing, but it has little to do with the recent price increase of oil, and much more to do with oil companies trying to protect their privileges by destroying the regulatory power of government. They do that by forcing tax cuts on government, and trying to "starve the beast". Did you notice that the recent quarter of -.1% GDP decline was caused entirely by reductions in government spending?

Nick – “I'd say most "demand destruction" has to do with low value energy use being eliminated (by insulation, for instance), and low cost greater efficiency”. I suppose a fair question would be do you have studies to back that statement up? You may be correct for all I know. OTOH I don’t need a study to tell me that when someone’s paycheck stops coming in they cut back on just about everything including energy. Again whether that’s a big percentage of the decrease or not I don’t know. And then there’s the folks who still have jobs but see higher energy costs and cut back on energy usage…especially if they think their job may be in jeopardy. I know a fair number of upper middle class folks who have cut back on their travels both driving and flying.

Certainly insulation and other efficiency gains would help but I suspect there’s a significant time lag for that to show up compared to folks getting fired or just scared about it.

Also, I curious: which oil companies forced the govt to make tax cuts and how did they do that?

do you have studies to back that statement up?

Not on hand - I'd love to see a good analysis. US oil consumption is now well below where it was in 1979, even though the economy is 2.5x larger, and manufacturing output is 1.5x larger. It's pretty clear that in the longrun efficiency and substitution are the reasons for declining oil consumption.

More recently, I think we can be confident about heating oil reductions. Of course, oil for generation is dropping quickly in the US. Even in places like Hawaii, where rooftop PV is now much cheaper than grid power.

US industrial output is as high now as it was at the roughly 2007 peak of oil consumption, so Gail's assumption that industrial decline is the culprit for industrial energy consumption reductions is incorrect. Petrochemical companies are reducing oil inputs as fast as possible. Have you looked at the shape and thickness of plastic bottles lately?

The dynamics behind reduced VMT are more complex. VMT is being by reduced a number of things - online ordering & socializing, carpooling (which is larger than mass transit in the US), generational change. We can see in Gail's chart that VMT annual growth was declining well before the recent oil price shock.

I suspect there’s a significant time lag

Sure. short term demand elasticity is much lower than long-term.

which oil companies forced the govt to make tax cuts and how did they do that?

It wasn't oil company staff so much as oil company owners - the Koch brothers are the most visible. They've funded a long-term effort to cripple government. They don't hide that, though they like to minimize their involvement in the specifics, like funding the Tea Party astroturf, or various "free market" think tanks (Cato, etc).

Oil consumption is flattish and primary energy consumption is up about 20% or so over that timeframe which is much less than the increase in population. The missing piece of the puzzle to me is how much of the energy consumed over the years was exported (both explicit as well as implicit). I would not be surprised that in the late 70's/early 80's the US exported more "things" (with significant embedded energy) versus today. It's important to keep in mind that part of energy consumption goes towards production, something which you can see quite cleary in China for example. As the US imports more things from other countries we may seem to use less energy but part of that is because of outsourced energy use for manufacturing. And the same goes for the labor component of production of course.

Rgds

WeekendPeak

Unfortunately, in 1979 the US was running a trade deficit just as it is today.

US manufacturing output is 1.5x larger now than it was then- that rules out outsourced energy use as a primary cause of the decreased oil (and other energy) consumption.

Gail wrote:

Most of demand destruction has to do with people losing jobs-- Jobs seem to move to countries where costs are cheaper--wages lower, more coal use, etc. I would call this demand destruction pretty negative.

Nick replied:

I don't think you've done the research and analysis to support that. That's just an assumption.

Now I have heard it all. There is actually someone on this list that don't believe people are losing their jobs because of demand destruction. That's just an assumption. Yeah, right!

People are losing their jobs, not only because the jobs are moving overseas where there is cheaper labor, but also because people are spending less on petroleum products. People are traveling less. That means people in the travel industry are losing their jobs. Motel and hotel workers are losing their jobs. People are eating out less. It is a different world since petroleum prices started to skyrocket in the first part of this century. (Brent price was below $10 a barrel for much of 1999.) And US oil consumption has dropped rather dramatically in the last decade. And most of that drop was due to demand destruction.

Not only that but because labor is a buyers market now, people are working for less. They have to take less or not work at all. And it was, in my opinion anyway, brought on because of the high price of oil.

Demand destruction is a very destructive thing.

Ron P.

the jobs are moving overseas where there is cheaper labor

Except, that's not really true. Job losses are primarily due to automation, and secondarily due to the collapse of the housing bubble - that's a lot of realtors, mortgage brokers, carpenters, etc, out of work because no one needs new houses right now.

People are traveling less.

Plane passenger miles only down by .-9%. As we saw above, VMT is only down by roughly 3%, and that has many sources besides reductions in "travel", including shifts to carpooling, transit, online shopping, young people deciding walk and bike, etc.

http://apps.bts.gov/xml/air_traffic/src/datadisp.xml

People are eating out less.

That's up by 11.5%, since 2007 - http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-expenditures.aspx

I wrote:< the jobs are moving overseas where there is cheaper labor...

You replied Except, that's not really true.

Good gracious man, are you serious? I live in a town, Huntsville, AL, where there once 13 textile mills. Now there are none. Now they, along with almost every other textile and clothing manufacturer, have all moved overseas, to Bangladesh, to Taiwan, To China, to other places where labor is cheap. Birmingham, AL, once had the largest steel plant in the South. Now it is gone.. to Japan along with most other steel plants. Most all electronic, plants like Zenith, RCA, and others, have all either gone under or moved to China and other such places. All your TVs and electronics are now made, mostly in China. Slave wages are paid.

Shoes are no longer manufactured here. Virtually all labor intensive manufacturing plants have all left for foreign shores. A few automobile assembly plants remain but not much more.

And you have the audacity to say that is not true? Goodness man, you have now lost all credibility.

Ron P.

He's correctly saying that the primary cause of lost manufacturing jobs in the USA is automation, not outsourcing. This has been widely reported for years; see, for example, here or here.

Your links spout pure nonsense Pitt. Do you actually believe that robots are manufacturing clothing in the US? Do you actually believe that robots are making shoes in the US? And there are a thousand other items that were once made in the US that are no longer made in the US, not by man and not by machine. They are made in third world countries by workers working for near slave wages.

These things, from clothing to shoes to electronic products such as iphones and TV sets are not being made by automated robots in the US. They are not being made in the US at all. They are being made in China by people. And those people work for a fraction of the wages that a dishwasher would demand in the USA.

Of course automation takes jobs. That is a given. But there are some jobs that robots cannot do. A robot cannot make a dress, or a shoe, or a hat, or put together a delicate electronic device like a cell phone. Those jobs must be done by people.

Apple supplier halts China factory after violence The factory that makes Apple's iPhones employes 79,000 people. Most of them live in a dormitory because that's all they can afford. But when you pack people together like slaves, there are bound to be problems.

Now iPhones could be made in the US if robots could make them. But they cannot so they are made in China where workers are paid slave wages and housed like animals.

And that Pitt, is why US jobs are being shipped overseas.

Ron P.

I'm not sure the most productive method of discussion is to simultaneously agree with the main point of a position while deriding it as "pure nonsense". That style of rhetoric makes it hard to discern what you're actually trying to be serious about.

I'm not sure you understand what "industrial automation" means. It doesn't mean "fire a human and put a robot where he was working". It means "give human workers better tools to do their job faster and more efficiently".

It means "give a seamstress a sewing machine instead of a needle and thread. She'll be able to get her work done 5 times faster, which means she can do 5 times as much work per shift, which means you'll be able to make the same number of dresses with only 20% as many people."

That is how industrial automation works, and that is why it's a downward force on the number of manufacturing jobs.

The fact that it's a stronger downward force on the number of US manufacturing jobs than outsourcing is interesting, but not terribly surprising if you've paid attention to the large gains in multi-factor productivity since the late 90s.

Jeeze Pitt, it is not "either this or that". It is not either automation takes jobs or outsourcing takes jobs, but it cannot be both. (Wrote while pounding my head against the wall.) Yes it can be both. Of course automation takes jobs and yes outsourcing takes jobs.

There is no denying that automation takes jobs. But to say that outsourcing does not take jobs is to bury your head in the sand. I gave you example after example and you ignored them. Do you deny that once everything in the textile industry was right here in the USA? Do you deny that the cotton was grown here, the cotton was spun into yarn and thread here, and the thread was woven into cloth here, and that cloth was sewn into garments here?

But nooooo, not any more. The bales of cotton that are still grown here are loaded onto boats and shipped overseas to where the mills are. Only the cotton is grown here, everything else, and I do mean everything else, has been outsourced. There was once a shoe factory just a few miles from where I am sitting right now. And there was another just 100 miles north of where I sit, in Nashville Tennessee. And there were dozens more around the USA. They are gone gone now. If there is a single shoe factory left in the USA then I am not aware of it. Shoes are now made mostly in China and India.

And it is the same with almost every other industry. It is the same with every labor intensive industry that possibly can be outsourced. Any labor intensive industry that can possibly be outsourced has been outsourced! End of story.

Give me the name and address of those garment factories where the seamstress can do 5 times the work per shift. They are all in Bangladesh, India, China, Pakistan or somewhere where the wage is one tenth what it is in the US. The manufacturing jobs were not driven out by automation, they were driven out by the wage differential between here and there.

And it is not just clothing or shoes, it is electronics and just every other thing that requires lots of man hours to produce. It is the wage differential Pitt, the wage differential.

Pitt, everyone knows that. You know that. My 13 year old grandchild knows that and you know that.

Ron P.

...is not something I've ever done.

My point was simply to note and provide evidence for an interesting fact, namely that increases in manufacturing productivity has been a greater source of loss of American manufacturing jobs than outsourcing has. A greater source, not the only source.

It ain't so much what we know that gets us into trouble. It's what we know that just ain't so.

"Nine Things We All Know That Just Ain't So

3. Manufacturing has collapsed in the US

Most people know that manufacturing collapsed in the US, as jobs were shipped to China, with devastating effects on the once-productive Rust Belt. Thus in 1969, manufacturing accounted for 26% of national employment but accounts for only about 9% today. In reality, manufacturing output in the US is as high as it have ever been. One part of what happened to manufacturing was higher productivity. The decline in U.S. manufacturing employment is explained in part by rapid growth in manufacturing productivity over the past 50 years. Just as agriculture which once employed a third of the workforce now feeds the nation and more with only 2 percent of the workforce, so manufacturing simply needs much fewer people to produce the same output."

Outsourcing is real, but is only one factor.

Wrong. A huge chunk of the world's steel is made in China, with cheap Chinese coal. American steel can't compete with the price of Chinese steel.

China makes a lot of steel, but that doesn't mean that they stole it from the US. US production hasn't gone down much from historical levels:

Page 6 of the USGS steel report below says that in 2000 US raw steel production was 102M tons. In 2011 it was 86.4M. Thats 85% of 2000 production, and pretty consistent with the average production post-WWII. In 2000 US imports were 34.4M. In 2008 they were 14.7M, or less than 50% as large. Net steel imports dropped by 63% from 1978 to 2009:

Imports Exports Net-imports

1978 20M 2.97M = 17M

2009 14.7M 8.42M = 6.3M

Clearly off-shoring of US steel production is not the cause of declining US oil:GDP intensity.

http://minerals.usgs.gov/ds/2005/140/ds140-feste.pdf

Yes, you're probably right, although China is supplying a heck of a lot of steel, I don't know who the end users are. Never thought the steel production had much to do with reduced US oil output.

That is just not true. In dollar amount, no doubt but not in manufactured items produced. Almost all the textile industry has moved overseas. Almost all the steel industry has moved overseas. Almost all the garment manufacturing industry has moved overseas. Almost all the shoe manufacturing industry has moved overseas. And the metals industry, from steel to aluminum has been decimated by outsourcing. Yes these jobs have been automated but the automation is taking place in India and China.

Automobile assembly has remained here with but the foreign plants that are here, almost all the parts are shipped from Japan or South Korea to be bolted together in the US. I have a Hyundai that was assembled in Montgomery, Alabama and even the windows are stamped "Made in South Korea".

And about automation, call about your Visa bill and if you ever get through to a human being, they will be in India. And almost every electronic item in your house was made in China. Even the automated jobs are being shipped overseas.

Over 90 percent of the products Wal-Mart sells are manufactured in foreign facilities. Fifty years ago there was no Wal-Mart but 90 percent of the items sold at Woolworth was manufactured in the US of A as was the case in every other store, whether a hardware store, a clothing store, a shoe store or a five and dime store. Now the vast majority of items sold in any of those type of stores are made overseas.

Ron P.

Almost all the steel industry has moved overseas.

Ron, it may feel that way, but it's just not true: look at my comment just above.

Almost all the textile industry has moved overseas.

I haven't looked up the stats, but the terrible truth is that most of those plants would have closed either way. If they hadn't moved then production would have been consolidated at just a few, very productive plants.

Manufacturing of all types uses a wide variety of methods: work simplification, redesign, etc, to relentlessly reduce labor inputs by about 5% every year. If the industry matures and it's growth ends (like textiles) then employment starts dropping. It's like the shark metaphor: it either keeps moving, or it dies. Except, of course, that in this case it's only the employees that "die".

Over 90 percent of the products Wal-Mart sells are manufactured in foreign facilities.

At the height of the US post-WWII miracle, the US produced more than 50% of the manufactured goods in the world. Now, it's a much smaller fraction. In a world of international trade, the things on the shelf are going to come from places with funny names. On the other hand, the same thing is true in other countries: they see things from other countries. The US imports *and* exports.

Ask yourself: did you ever expect to see everything on the shelf of Walmart say "Made in Alabama"? No, right? Then, in a world of international trade, why expect everything to say "Made in the USA"?

Now, there's no question that the US has a trade deficit, and that some jobs have been outsourced. If other countries hadn't stolen some of our trade, we would have a larger manufacturing sector than we do. But, that doesn't change the basic fact that US manufacturing is as large now as it's ever been.

It is not a "fact" that US manufacturing is as large now as it's ever been.

I'm not sure what motivates you to continue to states things as fact that clearly are not. Perhaps you have an agenda or you just like getting people riled up. Whatever it is, isn't helpful to the conversation.

Umm..yes it is, as measured by things produced. It's not as large as measured by employment, that's for sure.

So, which do you mean? If it's the first, then please give some evidence for it.

As I stated below, the value added by the manufacturing sector has not even kept up with inflation let alone the increase in GDP. Value added is what we here in the US actually produce as part of the manufacturing process. It strips out the cost of raw material costs and imported parts.

And, how do you know that?

Here's info for you: See nice charts from a left-leaning source: http://www.counterpunch.org/2012/10/15/the-myth-of-u-s-manufacturing-dec...

and from the right: http://www.dailymarkets.com/economy/2010/10/03/increases-in-u-s-worker-p... .

Here's a good analysis of the impact of automation on routine employment in general: http://economistsview.typepad.com/economistsview/2012/11/jobless-recover...

Here's production data at http://www.census.gov/manufacturing/m3/index.html, including http://www.census.gov/manufacturing/m3/historical_data/index.html , especially Historic Timeseries - SIC (1958-2001), "Shipments".