Peak Oil Overview - July 2009

Posted by Gail the Actuary on July 20, 2009 - 10:07am

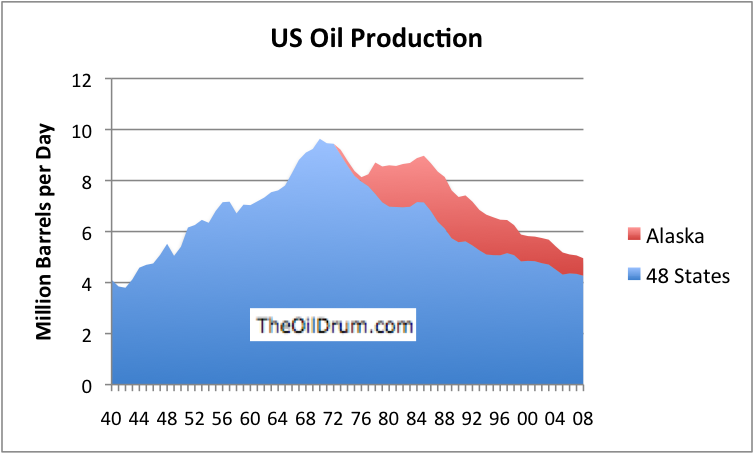

Most people who have read a little about peak oil have heard that US oil production peaked in 1970. This happened, even though oil companies have been working as hard as they can to keep production up. Oil companies have even applied enhanced oil recovery techniques to wells where it looked like doing so would be profitable. After the US mainland (48 states) peaked in 1970, extra effort was expended to ramp up Alaskan production. It soon peaked as well, in 1988.

The question now is with respect to world production. The price of oil isn't very high--is there any possibility of a near-term peak in world oil production? Lower prices would seem to suggest there is no problem.

It seems to me that if we look closely at the situation, world oil production has likely peaked, even though prices are not behaving as most had expected. Furthermore, the peaking of world oil production seems to be a major cause of the current financial crisis. The tie of peak oil to recent demand destruction points to a possible continuing destruction in demand in the years ahead, with oil prices fluctuating, but not necessarily rising to great heights.

1. Where are we now with respect to world peak oil?

There is considerable evidence that we may already be somewhat past the peak in world oil production.

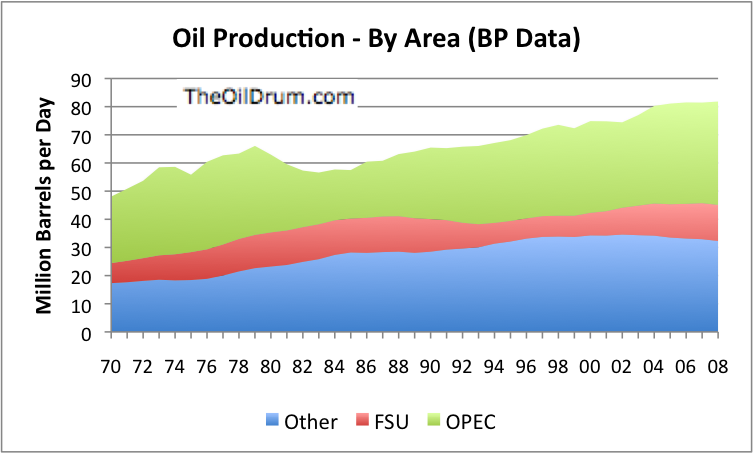

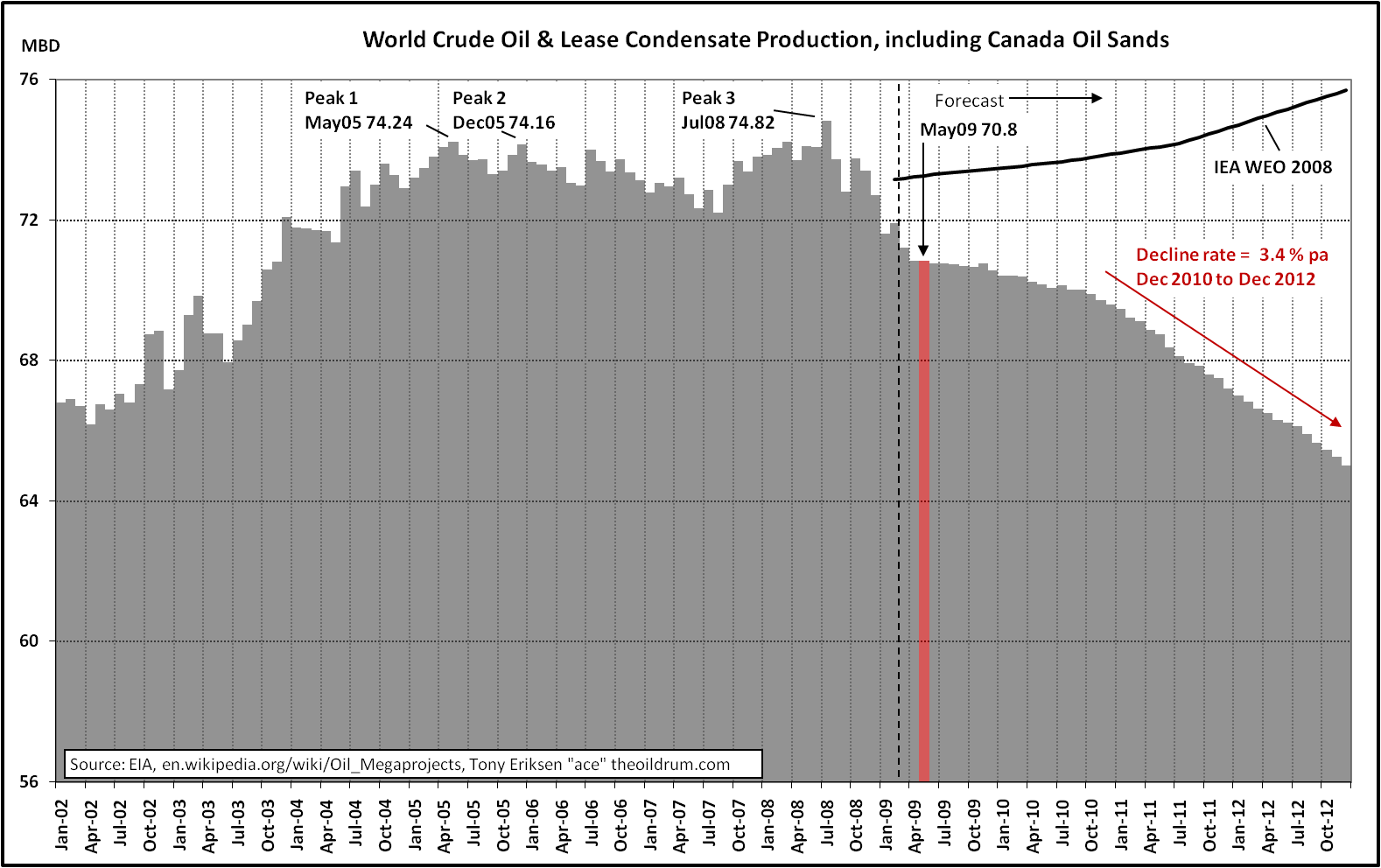

Figure 2 indicates that world oil production was rising up until 2005, but then leveled out in the 2005 to 2008 period, at a little over 80 million barrels a day of oil production. If we divide up world production into three components--Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countires (OPEC), Former Soviet Union (FSU) and All Other, the three groups act quite differently.

OPEC production bounces around, as production is raised and lowered because of planned production changes, wars, over-production and need to rest fields, depletion, and response to market conditions.

FSU production reached a peak prior to the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1990. It is currently at a new lower maximum (still rising, but not quickly), with the application of new technology and additional investment.

Oil production for the big group of All Other countries (shown in blue on Figure 2) is characterized by more steady investment. When one considers the steady investment, production for this group has almost certainly peaked. This group would include US, Canada, the North Sea, Mexico, China, and many smaller oil producers not in OPEC or the FSU.

The peak for this group occurred in 2002, with a plateau occurring more or less in the 2000 to 2004 period. Once this group started declining, there wasn't enough of a production increase elsewhere (FSU and OPEC) to bring total production up. One could argue that this was just because FSU and OPEC chose not to increase production more, but there seems to be more to the situation than this.

2. What makes you think that world oil production has peaked? Figure 2 just shows that it has been flat recently.

There are several things:

a. Recent drop in world oil production. In 2009, there has been a drop in oil production, that doesn't show up in the annual data in Figure 2.

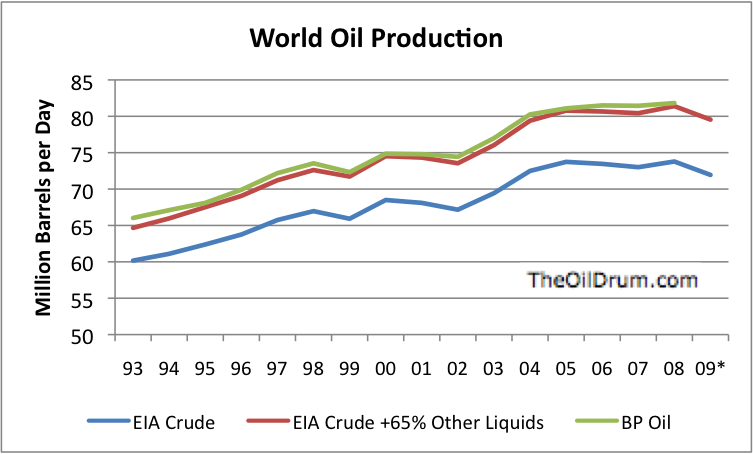

There are a number of sources of oil production data. Figure 3 compares three measures of oil production, two of them from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), the official US source of data.

The EIA now reports a broad measure of oil production called "all liquids". It includes everything from crude oil, to natural gas liquids, to refinery gain, to ethanol. The problem with this measure is most of the "other liquids" are lower in energy content than crude oil. They have been growing by volume in recent years. I have attempted to correct for the lower energy content by showing a line called crude + 65% x "other liquids".

One can see that with each of these measures, oil production is clearly down in 2009. In fact, since oil production was close to flat between 2005 and 2008, with the drop, production for 2009 year-to-date is at or below the level of 2004 production. Since population is rising, and the number of vehicles in use is rising, this is truly alarming.

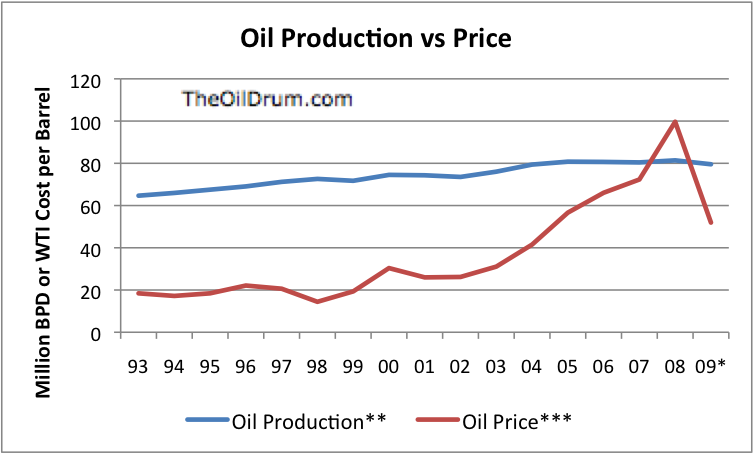

b. Strange behavior in oil prices in the 2003 to 2009 period. One would expect oil prices to rise with the general inflation rate, but instead prices rose much faster than inflation in the 2003 to 2008 period. Then, a sudden break came, and oil prices dropped from $147 barrel to $30 barrel in the second half of 2008. Oil prices have since risen to above $60 barrel. (The graph shows only annual data, so you cannot see this detail.)

The long rise in the price of oil between 2003 and 2008 seems to indicate production of oil was not rising as much as was needed by the economy and the growing number of vehicles. Oil prices were rising to encourage increased production.

According to economic theory, higher oil prices should have lead to higher oil production (or substitutes-but the impact of biofuels is small, and included in "All liquids" in Figure 3), but this did not happen, suggesting that it really was not possible to ramp up production as much as the economy needed. Even if some of the price rise at the end may have been speculation, the price rise still did not result in much of an increase in production.

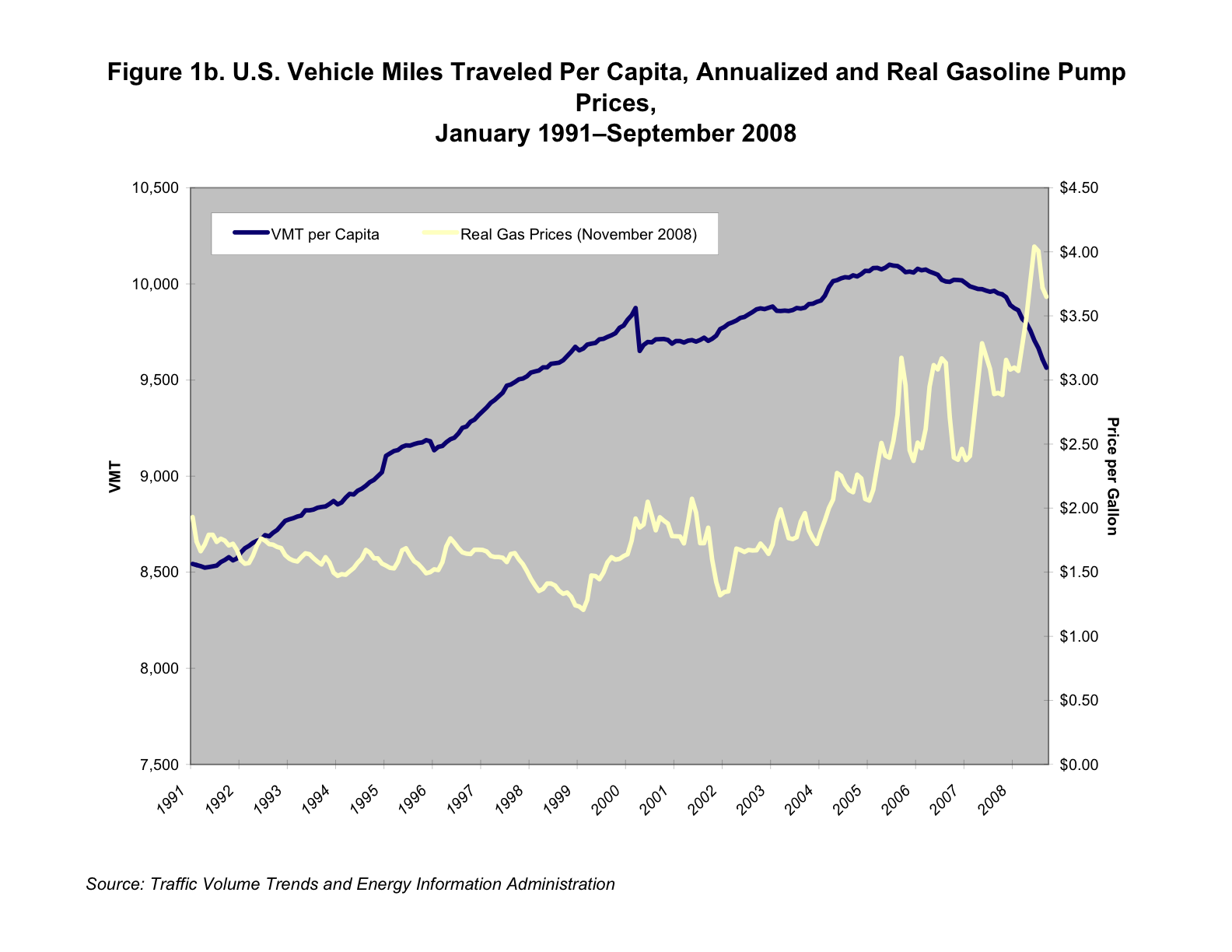

It should be noted that the rise in energy prices started right after the production of the "All Other" group in Figure 2 began to decline. It was at this point that a real increase in production was needed from OPEC or FSU to offset the drop in oil production from Mexico and the North Sea. While there was some increase in production, it was not enough of an increase to keep oil prices steady. Instead oil prices keep rising. In response, per capita vehicle miles traveled declined starting in 2005, according to a study by the Brookings Institution.

In the 2004 to 2006 period, the Fed, it its minutes, expressed concern about rising oil prices, and raised interest rates because it felt the economy must be overheating, if such inflationary effects were occurring. The combination of higher oil prices, higher food prices (caused by higher oil prices) and the higher interest rates set by the Fed in response to higher oil prices had a braking effect on the economy. People's discretionary income dropped. Housing prices began to drop, especially in the more distant suburbs, as people could afford less. People began defaulting on loans, and the financial condition of banks became worse and worse. Still, through all of this, oil prices continued to rise.

Finally, in July 2008, a break came. The economy could no longer tolerate the high oil price. Instead of rising higher, other changes started occurring, affecting the economy as a whole. Banks began cutting back on lending. This cut-back in lending, as much as anything else, caused demand for all kinds of products to drop, since without more loans, people couldn't buy automobiles and all of the other things they wanted, and without loans, businesses couldn't fund new investments.

Once the break in oil prices occurred, oil companies began delaying their plans for increased production, especially in high cost places like the Oil Sands in Canada, where it would not be possible to produce oil and make a profit at the new lower prices. The cutback in lending also affected some of the oil companies, forcing them to limit investments to what could be financed through cash flow from current production. Since prices were low, cash flow was low, further reducing investible funds. Production from existing wells continues to decline, and new investment is needed to offset this decline. With the current lower investment, though, the amount of new investment is almost certainly inadequate, so future oil production is very likely to drop.

Spikes in oil prices have in the past have been associated with recessions, according to Jeff Rubin. In addition, an econometric study by James Hamilton of the University of California at San Diego shows a link between oil prices and the current recession:

Whereas historical oil price shocks were primarily caused by physical disruptions of supply, the price run-up of 2007-08 was caused by strong demand confronting stagnating world production. Although the causes were different, the consequences for the economy appear to have been very similar to those observed in earlier episodes, with significant effects on overall consumption spending and purchases of domestic automobiles in particular. In the absence of those declines, it is unlikely that we would have characterized the period 2007:Q4 to 2008:Q3 as one of economic recession for the U.S.

If there is a single day for peak oil, it would be the day the price break took place. This was July 11, 2008.

c. Forecasts by Tony Eriksen ("ace") based on megaprojects data show declining future oil production.

Tony and others have put together a database of planned investments in oil fields called the megaprojects database on Wikipedia. This database includes all known capacity additions of 100,000 barrels a day or more, and is constantly updated. With the drop in oil prices, more and more projects have been pushed off to future dates. At the same time, existing fields continue to deplete.

Prior to the recent drop in prices, it seemed likely that production could continue to rise, at least for a few more years. Now with lower prices, enough projects have been delayed that based on Tony's analysis, oil decline can be expected for the next several years.

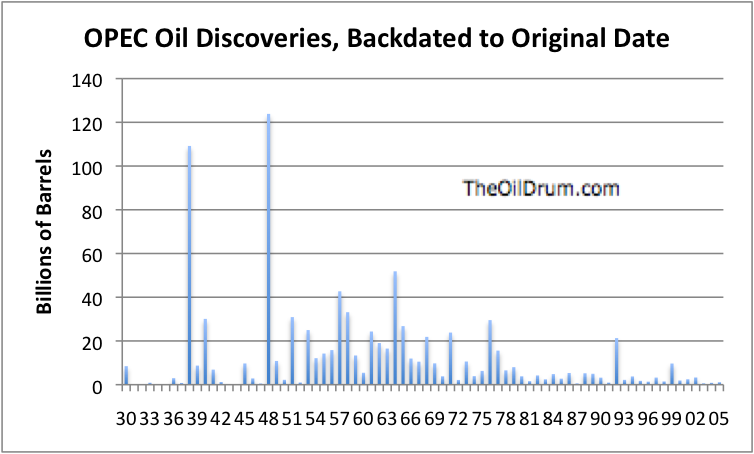

d. OPEC wells are for the most part very old. Decline can be expected in the not-too-distant future.

We really have very poor information about OPEC's true oil production capability. Several of the OPEC countries have published very high reserve estimates, but these amounts are not audited, and there is serious doubt that the actual amounts are as high as they claim. Also, we don't know how fast the oil can be extracted. We don't know if these high reserves mean they actually have enough to maintain, or increase, their current production levels. The reserves could also be consistent with a near-term drop in production, and a continuing dribble for hundreds of years.

Figure 6 shows that most of OPEC oil reserves relate to fields that were discovered more than 40 year ago. In fact, some were discovered more than 60 years ago.

The problem is that at some point, oil fields become depleted. Instead of being able to pump a constant or rising amount of oil out, production begins to drop rapidly, even with rising investment. In the United States, that drop in production occurred in 1970 (see Figure 1), about 40 years after production from its major oil fields began. In the North Sea, the time frame was shorter--about 28 years between initial production and the time when it became virtually impossible to maintain the prior level of production.

Several of the OPEC countries have not been pumping at maximum capacity for the full time and initial reserves seem to be quite large, so the time until terminal decline starts playing a major role is likely longer--but could be very soon.

We know that Saudi Arabia is using aggressive techniques to maintain it production. But at some point, these techniques are likely to stop working, and production may drop by as much as 3 million barrels a day quite quickly. We have heard reports that Saudi Arabia is "resting" 1.5 million barrels a day of production from its largest field, Ghawar. This may--or may not--indicate a problem in maintaining production in the field. If Ghawar (with at one point, 5 million barrels a day of production) should start declining rapidly, this would be a problem.

e. The FSU does not look like it can play a major role in offsetting declines elsewhere.

Russia represents the largest part of the FSU. Its production seems to have recently started declining. Investment available for further development is limited by the lower oil prices, so Russia's production is likely to continue to decline. The production of the other countries in the FSU are relatively small. Their production may be able to offset Russia's decline for a few years, but are unlikely to add enough to offset much of the "All Other" decline in Figure 2. As a result, the vast majority of the decline in the "All Other" category will need to be made up by OPEC.

3. Can't OPEC adjust prices so that they are just right--high enough to keep production rising, and low enough so the world economy will not go into shock?

There are a couple of problems with adjusting prices. The first is that it is not all that clear that OPEC has that much control over price. Most members would prefer to produce "flat out", so it is difficult for OPEC to reduce production by very much, from their maximum available production. While we are often told that there is "x million barrels a day" in spare capacity, we have no way of verifying that that is in fact the case. So if production is down, we don't know if that is because of an intended cutback, or if it is because there are other issues (for Venezuela, inability to pay creditors; for Saudi Arabia, need to rest wells).

Apart from the difficulty in controlling the price, the real problem is that there really is no "sweet spot" where oil prices are high enough to encourage adequate production, but low enough to keep the world economy running. The US Fed found that even when oil prices increased from $30 barrel to $40 barrel back in 2004, this had inflationary effects on the economy, which they felt were necessary to control.

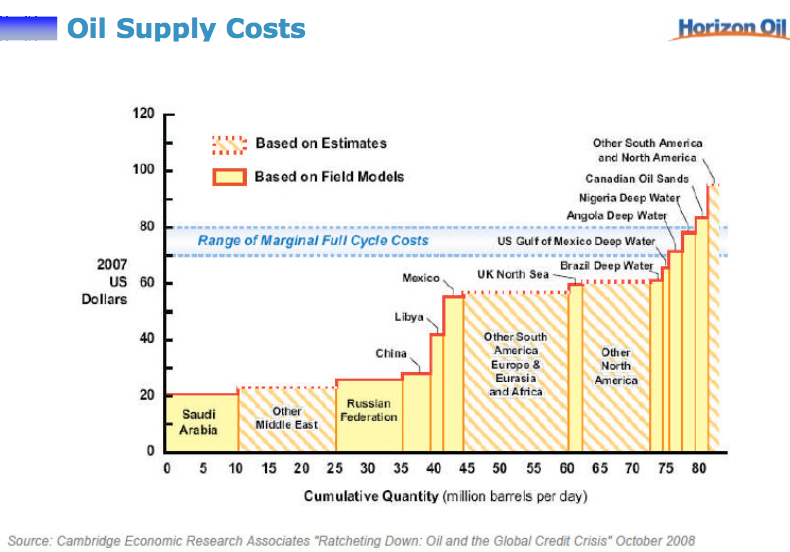

Clearly a much higher price than $40 barrel is needed to encourage production. We don't know exactly what that price is, but this graph gives an indication of the range in production costs:

In order to get oil production to rise, we need new oil production from even the most expensive sources, including new deep water production and oil sands production. This means we likely need oil prices of something like $100 barrel. The world economy cannot support such high oil prices, without people defaulting on their loans, banks getting into serious financial difficulty, and the whole financial system crashing.

4. Where can oil prices and production be expected to go from here?

Opinions differ on this, but my view is that I don't expect oil prices to go radically higher. Instead, I expect that oil prices will continue to fluctuate, and the economy to continue to collapse. Thus, what we will see will look more like collapsing demand than collapsing supply.

In my view, the underlying problem is the fact that the current level of debt (by individuals, businesses, and governments) cannot be maintained, unless we have a growing economy. The reason we need a growing economy for the debt system to work is the fact that a person can borrow from tomorrow, only if tomorrow is better than today. (This is especially the case if loans require the payment of interest.) But if tomorrow is worse than today, borrowing from the future doesn't work. Even if tomorrow is the same as today, the system doesn't work, if loans need to be paid back with interest.

The problem is that the economy cannot grow unless oil production is truly rising. This lack of growth in world oil production since 2005 is what is causing the debt collapse we are now seeing. This debt collapse is in turn giving rise to the demand destruction we are seeing currently. Since oil production cannot rise in the future, it seems to me that we are going to see a continuing unwind of the credit bubble that was made possible by rising oil production. Without credit, people will be unable to buy cars and houses. Businesses will be unable to finance new investment, and we will see greater and greater demand destruction.

The result will be oil prices dropping, more and more people unemployed, and fewer goods and services purchased. In short, the whole system will unwind from the demand side. At some point, there may be a major break, if the international financial system cannot stand the strain. There may also be political upheaval, both in oil producing countries (because the price is too low) and in oil consuming nations (because more and more people are out of work). The results are likely not to be very nice.

Gail, Great post and summary. Thanks for all you and the other contributors do. I have a sense that there are still a couple of pieces missing which I struggle to articulate.

As Sam and WT point out with the export land model, many exporters past peak will soon go to zero exports. While that is important, it doesn't seem to me to go far enough. As every former exporter moves from the export camp into the import camp, every subsequent depleted barrel they lose in production equals 2 barrels needed on the global export side to remain the same. In other word, there is now a barrel that was their previous contribution to available export which is not there, plus a second barrel which is now needed for them to import.

In a recent post there was also a chart showing the impact of decreasing EROEI. Although we may go into a slow global descent in production, a larger percentage of that production will be funneled back into future production leading to a reduced net availability for end user consumption.

With the havoc of the current economic situations, and increased cost of exotic explorations, risks factors may reach a point where future exploration is greatly curtailed. A single multi-billion dollar dry hole will greatly reduce investments, and money will tend toward the sure thing which means major players will buy proven fields from independents, and the independent wildcatters be fewer and far between.

I also sense that the majority of technological solutions (Horizontal/multilateral wells, fracturing, acidizing) in the oilfield work toward increasing the flow rates, and increasing cash flows rather than significantly increasing the ultimate recovery. We can suck the well dry faster, but don't get that much more out of it in the end.

Again, I have trouble grappling with these concepts, but to me at least, it seems we have reached peak and the impact of the decline may be more harsh and more rapid than many realize. Of course time will tell.

EJ

Some variations on the ELM

I assumed that we had an exporting country that hit peak production and then saw a production decline rate of -5%/year, comparable to Norway, Indonesia, Mexico, etc. The three variables that control the net export decline rate are consumption as percentage of production at final peak, the rate of change in production and the rate of change in consumption. If the rate of increase in consumption is fast enough, net oil exporters can slip into net importer status even as their domestic production increases, e.g., the US & China.

In any case, let's look at four variations of the ELM, using a constant production decline rate of -5%/year, and varying the rate of change in consumption (RCC) and varying consumption as a percentage of production at final peak (C/P)

(1) C/P = 50%, RCC = +2.5%/year; Net Exports go to zero in 9 years, with an 8 year decline rate of -28%/year

(2) C/P = 50%, RCC = 0%/year; Net Exports go to zero in 14 years, with a 13 year decline rate of -24%/year

(3) C/P = 25%, RCC = +2.5%/year; Net Exports go to zero in 19 years, with an 18 year decline rate of -22%/year

(4) C/P = 25%, RCC = 0%/year; Net Exports go to zero in 28 years, with a 27 year decline rate of -16%/year

All four of these models show that the net export decline rate exceeds the production decline rate of -5%/year and that the net export decline rate accelerates with time. An obvious implication of this is that net export declines tend to be front end loaded, with the bulk of post-peak cumulative net oil exports being shipped early the decline phase, e.g., Indonesia shipped 44% of their post-1996 cumulative net oil exports in only two years (1997 & 1998), as they went from final production peak in 1996 to net oil importer status in 2004.

I have recently reviewed 15 net oil exporters that have slipped into net importer status, or that have recently shown net export declines. All 15 have shown net export declines that are in excess of their production decline rates (or rate of increase in production in the case of China) and despite occasional year over year increases in net exports, the overall trend was predominantly for an accelerating rate of decline in net oil exports--especially for countries have slipped into net importer status.

Egyptian Net Oil Exports/Imports (EIA), result of declining production & increasing consumption:

(Egypt, 1996-2006: Production, -3.3%/year & Net Oil Exports, -29.3%/year)

Chinese Net Oil Exports/Imports (EIA), result of increasing production & fast increase in consumption (note difference in vertical scale):

(China 1985-1992: Production, +1.8%/year & Net Oil Exports, -16.9%/year)

WT re ELM

I have heard you review some of this info before, and I confess I still don't understand the implications.

Basically we have 30 odd countries who are exporters today

Each one of these falls into one of you four cases you outline here

So what you are suggesting (if i understand it)is that the decline in exports will be much, much faster than the overall global decline (lets say 5%), or the global decline as applied to available exports (lets say 8% or 9%)

what you seem to be suggesting is that the decline rate in available export crude will be 15% or 20% or more, once it kicks in, when you aggregate all countries

... but we have not seen this yet in the aggregate... is that becuase as Indonesia or Egypt crashes, we have a Nigeria or other to take its place

but soon there will be no new exporters. and so we will be hit with the full impact of the exporters...

could you explore the global implications of your hypothesis, and suggest where you think we are today on a global basis, and what we could expect in the next few years?

First, high flow rates can be quite misleading. As I have frequently pointed out, Indonesia's final production peak was 1996, and their net exports fell in 1997, before rebounding in 1998, so that their 1998 net export rate was only 9% below their 1996 rate--this doesn't sound so bad, except that by the end of 1998, they had shipped 44% of their post-1996 cumulative net oil exports, with the remaining 56% being shipped from 1999-2003. In 1997 and 1998, Indonesia was shipping one percent of their post-1996 cumulative net oil exports about every 17 days.

As you know, Sam has done quite a bit of modeling of the top five net oil exporters--Saudi Arabia; Russia; Norway; Iran and the UAE--accounting for about half of world net oil exports. The 2006-2008 data points are falling between his middle case and high case, which suggests that they will collectively approach zero net oil exports around the 2033 time frame. However, as noted above, net export declines are front end loaded. A ballpark estimate is that the top five will have shipped about one-third of their post-2005 cumulative net oil exports by the end of next year (one third gone in five years), with about 60% having ben shipped by the end of 2015. Currently, Sam's estimate is that the top five are shipping one percent of their post-2005 cumulative net oil exports about every 50 days or so.

We are focused on the top five because they are easier to model and they are the key contributors to the total volume of net oil exports, but consider three smaller, but still major, net oil exporters--Canada, Mexico & Venezuela (CMV), which represent three of the top four sources of imported oil for the US. From 2004 to 2008, their combined net oil exports fell from 5. 0 mbpd to 4.0 mbpd.

The point of my comment about the 15 case histories is that I have not yet found an example of a net exporter of any size, say a few hundred thousand barrels per day or so, which is showing or has shown lower production, and that is not showing an overall net export decline rate that is faster than the production decline rate. So, the expectation is that as more exporters peak and start declining, the aggregate net export decline rate will exceed the exporters' production decline rate and that the net export decline rate will tend to accelerate with time. And again, net export declines are front-end loaded, with the bulk of net exports being shipped early in the decline phase.

The disconnect between "Net Export Math" and the conventional wisdom of near infinite fossil fuel supplies is breathtaking.

Another way to look at it is to consider Nigeria with a population of 140 million heading fairly rapidly to 300 million.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_Nigeria#Population_and_Popu...

If Nigerians lived the non-negotiable American way of life the intrinsic right of a person living in a free democracy they would be a huge oil importer around 8mpd.

With very few exceptions most oil exporting nations would be major importers if the lifestyle of the population was even close to that of the US.

In general the oil age was only possible because the populations of oil rich countries in general live in abject poverty makes you wonder and hopefully it makes net export math more sensible. Basically any change in the living standard upwards rapidly drops net exports to zero in most oil producing countries.

If the populations in exporting countries are rising, just maintaining the standard of living [same per capita use] the internal use of the country will rise. Will exporters sacrifice their populations for the sake of continuing to have positive trade balances?

Vicky

A copy of a post I made on the DB thread:

Let's assume that you are sitting in a commercial airliner, about to take off on a New York to London flight, and you get three different evaluations of fuel on board, from the pilot, co-pilot and from a relief pilot.

The pilot says that he calculates that we have plenty of fuel for not only London, but a grand tour flying over European capitals, returning to London at our leisure--with plenty of fuel on board for a non-stop round the world trip if we wanted to try it. The co-pilot says that he estimates that we have enough fuel to get to London and for a controlled descent for landing. The relief pilot says that he calculates that the plane will run out of fuel about half way across the Atlantic, and he wants off the airplane.

The three pilots respectively represent the conventional wisdom view of virtually infinite fossil fuel resources, the Peak Oil view and the Export Land Model.

:) now we are getting somewhere. Memmel, bring over that kettle of hot water ! Last tea anyone ?

Very good metaphor.

The Peak Oil pilot might be a bit optimistic, though ;-)

ERORI can be tricky. Much of the energy invested is electricity and natural gas, at least in refinery operations. Does declining EROEI result in relatively higher exploration and production costs, and is E&P more oil-intensive than refining?

From the data I have seen the largest energy expense is the steel casing pipe. So I would say E&P is more coal and NG intensive than oil intensive. I don't know how the energy balance works out with deep water, hydro frac or heavy oil. Heavy oil is likely to be strongly NG biased.

Other questions:

If we effectively abandon some of our existing coal infrastructure, what does this do for EROI calculations? How many years can we expect new infrastructure to last (and therefore expect amortization over), in a world with less oil resources? Does Liebig's Law of the Minimum become effective early on?

ESTAMOS

You have made a key point that I don't think has been discussed on TOD:

"While that is important, it doesn't seem to me to go far enough. As every former exporter moves from the export camp into the import camp, every subsequent depleted barrel they lose in production equals 2 barrels needed on the global export side to remain the same. In other word, there is now a barrel that was their previous contribution to available export which is not there, plus a second barrel which is now needed for them to import"

thus if the decline rate of the world is 5%

5% of 74MBD = 3.7MBD

but its not 74 we should be looking at, its 44MBD which is the total world exports

this is the only number that counts

3.7 / 44 = 8.4%

Poly,

Thanks, yes that is what I have been struggling with. The impact is that net exports are falling faster than the production drop, because exporter internal consumption is increasing. Also former exporters are becoming importers, vying for a share of the available net export. Metaphorically our export pie is getting smaller, but now we need to divvy it up into more slices. The size of each respective sliver will be reducing at a rate faster than the overall pie.

ej

Again, there are three key variables: consumption as a percentage of production, rate of change in production and rate of change in consumption that determine the "glideslope" of a net export decline.

Two examples: (1) China went from (net) exporting about 600,000 bpd to net importer status in eight years because of rising consumption, even as their production increased, while (2) the UK went from (net) exporting over one mbpd to net importer status in seven years because of falling production; they had almost no increase in consumption.

One more compliation: I wonder whether Exporter consumption will continue to rise in a post-Crash world. Are their economies really that insulated? I can imagine destructive feedback loops.

I think it would be hard to constrain exporter consumption, because people in exporter countries live near the vulnerable oil infrastructure. Make them too unhappy, and they will start blowing it up, as we've seen in Nigeria and Iraq.

I agree that Nigeria is a prime example of what happens if a country tries to minimize domestic consumption. In any case, so far I haven't found a single example of an exporting country with declining production where the net export decline rate did not exceed the production decline rate.

I didn't mean to "try" to minimize local consumption. I meant, maybe their economies will tank too, lowering consumption. The premise of this article is that economic destruction willdrive oil prices lower at the same time. Won't that affect exporters economies and, thus, consumption? An unemployed Iraqi drives less just like an unemployed American.

Just an idea.

EJ,

Your comments are what I would call exponential growth, in reverse, with a double whammy!

Regrettably, your thoughts that the decline may be harsher than first thought, may prove correct?

A really nice summery Gail.

I agree with your basic position. I think we will see a pattern of price spikes and dips. But we won't see extremely high prices until the least efficient parts of the economy have been "demand destroyed". And who knows, that could be 30% of the economy destroyed before what is left will support a $200 per barrel oil price.

I think Jeff Vail had a nice graphic in his Oil Demand Destruction article. Different pieces of the economy are more or less efficient at turning energy into useful products. Those that are more efficient can support higher prices. The range of pieces causes a different kind of price behavior that if demand were uniform.

The financial sector is extremely efficient at turning oil products into GDP, but I see its place in the next few years as falling apart rapidly. It seems like other service sectors will collapse as well--how often does one need one's hair cut, or toenails painted. In fact, how much of the population do we really need to send to college or graduate school?

At the same time, we see a call to make huge changes to our infrastructure--like more transmission lines, more railroad capacity, more wind turbines and more electric cars. Building all of these things will take a huge amount of oil, with a payback over many future years (we hope).

So it is not obvious to me that we will see a big improvement in "efficiency" going forward, even though we may think we are working in that direction. We may spend more of our oil resources on things that don't bear results quickly.

If we look at the third world or any traditional culture, personal grooming services are are the very core of the service sector. They require almost no physical resources and they meet a basic human need - to look and feel good.

We may lose the boutiques but the hairdresser has a job for life.

Education and infrastructure don't stand a chance...

and don't forget dendistry , one's teeth are essential

look at the old civilizations - dentistry was a binding concern!

Forbin

Yes, the "barber" was an important figure a few centuries ago, cutting off unwanted growths, pulling teeth, and so on. Let's hope somebody somewhere is stockpiling topical Lidocaine, or at least clove oil.

But I think it's a fool's game to bet on future COMEX oil prices, which are not predictable and may not even be meaningful in a time of shortages.

The rubber band stretched tight last Summer, the economy snapped down in response to high oil prices (IMO), and the overshoot then pulled down the oil price. It's rebounding now, but how far depends on too many variables in both the supply and the demand sides of the equation. It's easy enough to predict volatility, but about what mean?

Unless we'd care to venture a guess about the political scene, we can't say whether in the short term the oil price will drive the economy or vice-versa. Yes, in the future oil must become less affordable, but no, that does not imply a higher price.

Personally, I'm ready to go short again in most of the indexes, but I'm steering clear of oil altogether.

Of course it will be rocky early but we are part of nature and thermodynamics will prevail.

We always take the path of least resistance when it presents itself.

Live and learn I guess.

All of these things can be built without huge amounts of oil. In fact, most of the country's railroad lines were built without huge amounts of oil, back in the 19th century. They were built in most cases with what amounted to slave labor.

Gail,

"At the same time, we see a call to make huge changes to our infrastructure--like more transmission lines, more railroad capacity, more wind turbines and more electric cars. Building all of these things will take a huge amount of oil, with a payback over many future years (we hope)."

You regularly make these claims, I think they are all wrong. In the case of wind turbines oil accounts for less than 5% of energy used( mainly transport to sites) and the total energy is returned within 6 months. For transmission lines, electric cars ( mainly steel and aluminium) the only oil is used for mining ores and transport of components.

Most oil in US is used for truck and light vehicle passenger transport, heating oil and jet fuel. Very little is used for farming(2%), rail or ship transport(5%), mining or manufacturing(?). With the exception of jet fuel most uses can be replaced by NG or electricity ,generated by NG, coal or renewable and nuclear.

Most of the oil used for manufacturing and construction is used by the employees in their ICE vehicles averaging 25mpg. The room for improved efficiency in private transport is "huge" and the payback very rapid if oil prices continue to increase.

I'm on the fence between your and Gail's analyses..

I do think there are ways to build what we need, particularly by reallocating MFG assets that have been making fripperies and widgets, say.. but aside from the sheer volume of Oil required to make Electric Cars, Grid Lines or Wind Turbines, say, is the bottleneck effect in the overall transportation sector.

EVERYTHING we make, buy and sell is affected by the tagline..

"If you bought it, a truck brought it." (While there are surely particular exceptions, a vast majority of shipped components within our trade goods are only one hand-shake *{degree of separation} from a vital Truckload.)

jokuhl,

I would agree that almost everything we use and make involves oil, that's only an issue IF suddenly there is NO oil or IF we use a very large amount of oil for most of these processes.

Clearly we use a lot of oil for transport, but a lot of that is single passenger commuting and light commercial vehicles. The really essential transport miles( rail and ship) don't use very much and rail in time can be converted to electric.

"but aside from the sheer volume of Oil required to make Electric Cars, Grid Lines or Wind Turbines,"

That's what I am challenging, is it really a high volume of oil for these activities?

."..is the bottleneck effect in the overall transportation sector."

Agreed transport is absolutely essential and oil is essential for transport, but that doesn't mean a high proportion of the oil presently used for transport cannot be replaced by electricity and higher fuel efficiency. We don't have to replace all oil tomorrow we have to replace the DECLINE in oil availability by efficiency and a much smaller ( in BTU terms) amount of electricity AS OIL DECLINE OCCURS.

The big exception is air transportation, this will have to contract.

Neil1947,

I don't say that Gail is "wrong" per se, because I do not know what scale of re-engineering and restructuring she is using as a model, but I do think that the consumption of oil in restructuring the economy is sometimes greatly overstated.

According to graphs that Gail herself has linked us to almost all the oil we use is burned, i.e, it goes to Diesel fuel, gasoline or heating oil, up the smokestack or out the tailpipe. Very little is used for "other" such as industrial applications, chemical applications, etc. This is mostly provided by natural gas. Thus the changeover to a more efficient energy system could raise crude oil consumption some but is more likely to have an effect on natural gas consumption.

The most promising return is of course the plug hybrid car. Almost all of our oil is consumed in transportation, and this sector promises the most improvement fast. As regular sized vehicles are shifted more and more to plug hybrid, crude oil consumption per mile is reduced and crude oil consumption flattens and then begins to drop. The plug hybrid is the most acceptable technology to the public that can radically reduce crude oil consumption.

We are in an interesting period: Oil producers are much more frightened of demand destruction than lack of supply. This means they are not willing to make the long term investments needed for oil production. We must recall that the investment in oil production cannot be expected to pay off in less than 10 years or so, and the producers simply cannot be assured of demand levels they need to pay for the investment as fast as the alternative technologies are now moving. Carbon release issues will only accelerate incentivization of the plug hybrid vehicle. Friends, we are seeing a pivotal shift away from crude oil as the driver of growth in the world. The race is now fully ON. The nations that adapt fastest will be the power players in the world for the next century. Those who do not will abide by their will.

RC

The calculations for restructuring the economy are fairly easy; there won't be enough in the diminished future because there isn't enough in the less- diminished now.

@ 80 million barrels a day, there is almost no restructuring taking place. Without anyone paying attention, the world shifted from a 'total growth regime' to an allocation regime.

An allocation regime requires choosing between commercial investment or energy use. In a total growth regime it would be possible to order- up both at the same time.

The allocation model has been gaining force for at least ten years. Actual hard- cash plus massively leveraged investments have taken place in demand- only areas such as housing, commercial real estate and in conventional auto- building capacity. All of this so- called 'investment' has amplified consumption. Investment directed toward energy production has been inadequate and grudging (Simmons). During the same period actual, net energy consumption itself increased. This is before the total of just- built demand has arrived in the market! The support of simultaneous commercial investment (on energy use) and energy demand required a dangerous increase in credit and risk. Every marginal increase in credit reduced the ability to allocate effectively by stacking risk and redirecting allocations away from energy production toward supporting financial institutions.

Energy- centric allocation was not and is still not considered necessary by the economic/political establishment. This form of blindness is likely to prove fatal to economic development as once reserves are directed into the credit 'black hole' there is less available for 'brick and mortar' investments in energy production or consumption efficiency. This is the main point Gail is making.

The US not only borrowed cash money from the future, but also borrowed a great deal of energy, as well. In demonstrating how to do this 'paying foward', Americans have stimulated excess demand for energy worldwide, particularly among countries who can leverage lending against their energy- derived cash flows.

See any of weatexas's posts here @ TOD. By means of US- derived finance credit, oil producers quickly became large consumers, building thousands of miles of highways and filling them with tens of millions of cars.

In order to have the kind of commercial growth that you suggest, it would be necessary to not purchase oil at all and direct spending toward energy investments. If there was no oil consumption, there would not be enough economic horsepower to effect the desired restructuring. If one chose to purchase oil, one would be restricted to both the legacy fleet of oil- consuming equipment AND legacy oil producing infrastructure. Both sets of which are deteriorating rapidly.

To produce new energy sources and still maintain consumption against current demand would require supply in excess of that demand to price crude @ a very low level: Think $30 oil. I don't know what that supply/demand ratio would be but last years' low would suggest an available supply over a considerable time of 88- 90 million barrels per day over 2008 consumption. Any increase in demand would need additional supply + 4 or 5 mbpd.

It's the money directed toward supporting consumption that is pulling the world away from alternatives. This leaves inadequate funding available to support restructuring; building a to- scale increase in the hybrid vehicle fleet for example. The costs of the fleet 're-engineering' that has taken place so far has been internally subsidized by manufacturers by the sale of large, gas- guzzling vehicles like SUV's and giant pick-up trucks. These vehicles were sufficiently profitable to allow makers to charge less for gas- efficient vehicles.

You might check Money and Markets. Martin Weiss PhD. has made a brief examination of the last Federal Reserve Quarterly Flow of Funds report.

It is hard to read - no, not the eyeball- numbing charts - its its sober and ominous content. There is simply not enough cash in the till to make grand restructurings.

We are broke!

You are right about not having enough energy/money to do everything simultaneously. It is hard for me to get numbers to put around what the problem is--partly because I am not sure the right numbers are published, and partly because I am not as familiar with data sources.

According to one report, the IEA estimated that global upstream oil and gas budgets were being cut by $100 billion, or 21% from 2008 levels. This would seem to suggest that in 2008, global upstream investment budgets amounted to $100 billion / 21%, or $476 billion.

As the "easy-oil" gets extracted, the cost of per barrel of extracting the remaining barrels goes up. So this hundreds of billion dollar amount goes up. Financing this becomes more and more difficult, especially for countries like Venezuela, with financial difficulties, and Mexico. As those who cannot get financing drop back, production is likely to drop faster than our models would predict.

The price barrier is unknown. There was no increase in output @ $100 per barrel prior to 2008. Would $200 generate more production?

No and that means that $200 ie simply a tariff. At that point the economic system is completely broken - what does $147 suggest?

That we are so ... so ... so very close to the edge.

I can understand people paying 'Large Dollars' for oil if it is used as an energy multiplier like Indium or Tellurium. Those elements leverage energy production and neither are directly consumable.

I presume your figures are all non- OPEC; let's use their figures and give them a trillion per year for capacity costs and compare this to the $20- plus trillion committed since 2007 toward consumption.

"Bbbut ... those moneys are investments ...!"

Yes, investments in autos, consumer and mortgage finance, commercial real estate, road building, communications (read 'advertising') and simply rolling over past loans for past consumption. Our goods wind up in the landfill inevitably. Our debt lives forever.

The produce- to- consume model is never scrutinized or put under administrative assault. It erodes from within as its capital base disintegrates, but you wouldn't know it by looking at the onslaught of consumption strategies. Our stance is (fatally) compromised by our viewpoint; we are so immersed in consumption that anything else fails to register.

$200 is too valuable to burn or the money paying for it is only good for burning. An honest $200 barrel cannot be leveraged into consumption. Consumption itself has too 'cheap' a return on energy invested. What is the borrowed energy worth? Since its product/proxies all wind up the the trash or in the atmosphere, the 'book' value of the energy that enables this is simple ~0 or less than worthless since atmospheric remediation has costs, too ...

That's the conceptual problem with EROEI; no liabilities to balance the assets. EROEI is about production, the greater balance sheet (game) is really consumption.

How does anyone balance EROEI against less than zero- worthlessness? How can anyone justify trillions in investment on some good that is simply wasted? What is the real value of the investment and how does one value alternative TYPES of investments? What do we do with all those energy 'slaves'? What are they worth? Nothing, obviously since we pay so little for them.

Can EROEI withstand any conceptual competitor that returns anything greater than -1 or -n or any positive number. We were gifted 100:1 EROEI and what did we do with it? Travel the solar system? Leverage more 100:1 energy systems with that original 100:1?

We humans 'had' WWII and we invented suburbia and SUV's. (Am beating head on wall ...)

$200 oil does not by itself bankrupt economies, it means economies are already bankrupted by $100 oil or $60 oil. This is done by default/repudiation or runs against currencies. $200 oil does not generate financial returns or increase energy returns. At this point there is no oil price funding level for alternative because there is no real economic activity. @ a consistent $200 price level there is much less oil sold. Increasing the price further reduces demand, diminishing the utility of the money spent even more. $200 oil is a collecter's item.

You are right, Gail; Post- peak feedback loops are hard to figure out. I suspect + $45 oil starts bleeding economies; that is what we are currently living.

I would agree w/ James Hamilton in that $147 oil did so much damage the outcome was reflected in the $34 oil ...

Those are parameters. I would say ~ $150 is the bomb. The next 'trend' low would be $40. Over resistance @ $78 and a retest of the 2008 high is next. That would wring more $trillions out of the nation's bank accounts; more deleveraging and another panic.

$40 ot $150 is a good swing. That by itself is damaging.

Great job, as usual Gail.

Agreed.

I think we're still in for some interesting price spikes still in our future so that our decline looks like this:

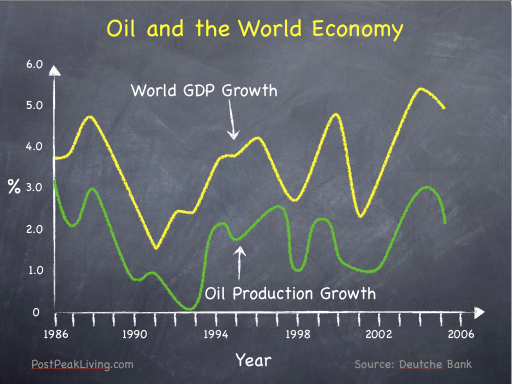

And Hirsch used this graph from Deutche Bank to show how completely dependent on oil we still are:

For a full estimate of our economic decline as oil declines, Hirsch's paper is an excellent starting point:

Mitigation of Maximum World Oil Production:Shortage Scenarios, Hirsch, 2008

It's behind a paywall so I've got a short writeup here that includes his paper and three others:

http://www.postpeakliving.com/blog/aangel/estimating-economic-impacts-pe...

-André

Thanks!

On Hirsch's graph from Deutch bank, I wonder what World GDP growth would look like, if we looked at growth in World GDP less the financial services industry. I bet the two lines would be quite a bit closer together.

I think your graphs are correct however I'd suggest that we simply don't know the prices as we take the second step. Related to my other posts in this thread peak oil is a rear view mirror type event. Only after peak is well in the past is peak oil important. We probably have made the first step down but its hidden if you will in many other factors. Esp as Gail point out in here reply in our economic system and financial system. Its when we make that second step that peak oil begins to become a clear economic factor.

We simply have not quite yet made the transition into the post peak oil economy and I don't think it makes sense to try and carry forward whats happened to date and assume it applies to what will happen as we make the second step. However its probably a safe bet that as we do make it the economy will recognize its in a post peak world.

Now I think your 100% right about where we are i.e just starting on the second step but its wrong to take the events of the first step and apply them to the second. We are hitting one of the biggest transitions in the last 100 years this year. From a cheap oil fiat currency/debt driven economy to a resource constrained ?????

I think you are correct that we are still operating in the "there will be a recovery" context and that is primarily determining investment decisions. It will take some time before there is a tipping point and enough people take their marbles and go home instead of risk them inside the current system. (I had a conversation on Saturday with a friend who is an investment advisor who is still advocating dollar-cost averaging. I bit my lip because I just wasn't up to the conversation after two beers in the rare warm sun shining down on San Francisco in the summer.)

I think the staircase graph shows the general outlines well enough though and I put question marks beside the prices for subsequent spikes because between deflation/hyperinflation/economic contraction/etc. it's impossible to tell what price will "damage" the economy further. I am certain, though, that there will be price spikes that — at whatever level they arrive — will cause the current participants in the economy some grief.

When enough people understand the concept of receding horizons, all it will take is one event to spook the market and everyone who was hoping to "make just a little bit more money before getting out" will run for the doors.

At that point the green line above goes virtually straight down. There are many other scenarios that can produce that result sooner but that one is building in the background, I think.

According to Chris Nelder's latest piece, "the smart money" is already leaving the system. He reports: "In their judgment [his associates who are managing large amounts of money], the markets are simply too corrupt to play anymore, and Goldman Sachs is Public Enemy #1 with alumni now staffing all the key posts at the Fed, Treasury, SEC, and on down the line."

http://tinyurl.com/nabjz8

I would want more data to say that what he reports is a trend but it is at least one data point.

For those interested in the idea of the receding horizon, please see:

You've Bought Your Last Car

http://www.postpeakliving.com/content/youve-bought-your-last-car

-André

P.S. for those interested, tonight I'm hosting an evening with Matt Stein, author of "When Technology Fails"...it's going to be an open question evening so bring your questions for Matt...for when our systems begin functioning intermittently or stop altogether....

I agree 100% with: "We simply have not quite yet made the transition into the post peak oil economy and I don't think it makes sense to try and carry forward whats happened to date "

Please read the piece from Stoneleigh:

Eventually the dollar will collapse, but that time is not now (and a falling dollar does not mean an expanding money supply, ie inflation)

Energy prices are first affected by demand collapse, then supply collapse, so that prices first fall and then rise enormously

Ordinary people are unlikely to be able to afford oil products AT ALL within 5 years

http://theautomaticearth.blogspot.com/2009/06/june-17-2009-40-ways-to-lo...

Monthly/quarterly world production data can be obtained from the EIA's International Energy Statistics Portal.

No problem in finding the data. I was just trying to simplify.

A lot of people have trouble reading graphs. The more complex I make things, the worse it gets.

gail, do you have monthly data going back long enough to notice if the first quater of a year has higher or lower production than average? or is the monthly jitter just too random? if there is a lot of jitter, do you think the error bars on that the last point would be, if there isn't could you comment on the production difference of the first quarter of a year vs the year average?

thanks,

Andrew

(i tried to do a plot of the monthly data from the IEA website, but cyclones have skewed the means with 1 month big drops, as the series only goes back 4.5 years... )

In this particular post, I was just trying to pull together things from a variety of other posts, in as simple a format as possible, so that much of the story as possible could be told in one place, without getting into all kinds of details. The story is still pretty difficult to follow for a new reader, unless he/she is very persistent.

EIA data is generally a whole lot easier to use than IEA data. This source is monthly, and goes back to 1994.

In general, oil demand is highest going into winter, because so many use oil for heating. I haven't really researched how Jan - April compares to the year as a whole. Back in the "good old days", oil production was generally rising, so the second half of the year tended to have higher production than the first half of the year, just because of the general upward trend.

Forecast demand numbers by various agencies also give some idea as to seasonality.

Gail, Thanks for the pointer to that data.

RE: seasonal trends:

The above image is the mean difference between a 12 month average (centered on that month) and each months production.

The second series does not count any month which was more than 1MB/d lower than the previous month (9 months out of the series, which goes back to 1994), to ignore the effect of cyclones on seasonal trends.

On average the year to date production for jan-apr will be 194k above the year average (178k if you ignore cyclone effects), suggesting that any estimate of the mean production for 2009 is currently .2Mbpd too high (assuming a constant production, which seems to be optimistic).

In the whole scheme of things, 200,000 bpd isn't all that much.

Disruption by hurricanes is to some extent to be expected in the July - September period. June must be the month that a disproportionate amount of maintenance work is done.

I expect that that is at least part of the reason for higher production during October to March is the outages in the summer. Of course, the use of oil for heating during winter is the other reason.

Fundamental supply does control the price of oil !

Thats right the price of oil is not tied to fundamental supply levels. Consider the case of a fairly enlightened society like the EU that heavily taxes most oil products forcing demand lower than what it would other be because of simple price arguments. And consider the heavily subsidized situation in many oil producing nations leading to higher oil consumption than is "normal".

This demand side is thus heavily influenced by economic policy and this demand interacts with supply to result in a price. And last but not least the price of oil is controlled by a futures market. If the futures market does not expect a strong increase in prices for what ever reason then you won't see super steep contango and rising prices.

Now whats important and its something I've realized from following the futures market for oil over the last several days is to recognize that this market has yet to "price in" peak oil.

In short the recent price swings are not driven by a market recognition of peak oil. This should be fairly obvious if you follow the mainstream media where peak oil is still considered a fringe subject. I think all of us me included have read to much into the price movements of the last two years. Thats not to say that peak oil is not and underlying factor in the price movements but for financial markets its critical to differentiate between what I call key market drivers and underlying forces. Traditional market bubbles make it clear that fundamentals can be ignored for a surprisingly long time.

So I'd suggest that this key post is simply to early for the market peak oil has yet to arrive and only when its clear that the market is actually directly pricing in peak oil does it make sense to look at fundamental supply and the market.

This means of course that you have to dismiss the rise in prices in 2008 as a signal of peak oil from the market perspective despite the fact that fundamentals played a role in the rise.

I think if you really look at whats happened you will come to a similar conclusion that peak oil is not yet a important factor in the worlds oil markets. We are blinded by our own insight.

Why is this important ?

Well 150 a barrel is probably not even close to the price of oil once the markets start pricing in peak oil.

Who knows what the price will be but I'm now convinced we have not even come close to seeing it.

I suspect many people will be shocked at the market decision when it does wake up to peak oil.

:) thx memmel, you have a lovely way to give people the creeps! Adapting theses pesky trading algorithms to peak oil might take some time too...

I tried to find a children's story without success. It goes like this Momma was going to make her homemade soup and each child asked here to leave out a ingredient that they did not like. In the end the soup was only hot water.

Now we can look back at the past 18 months and realize that peak oil is just that hot water as far as the market is concerned if you treat cheap oil as cold water using the soup story analogy.

Once you subtract all the economic factors and assume that the economy simply grew to fast and resulted in temporary supply and demand imbalances the peak oil signal is so weak its hard to justify.

Instead if you look you will see the combination of rapid growth in China and India and flattening of growth in the oil supply played the biggest role in recent price history.

I'd argue that anyone who is willing to take a unjaundiced view of the market and its difficult to do if your peak oil aware will realize quickly that peak oil is simply not part of our current oil price.

This does not mean we are incorrect in recognizing that its probably the underlying driver for the current price situation but to put it in perspective peak oil is driving oil prices without market recognition and these rising prices have themselves had a secondary impact on popping the recent credit bubble. I argue that to date peak oil itself has been such a small factor it can readily be discounted.

To a large extent this makes a lot of sense if you really think about it because peak oil really just sets a floor on prices until its fully recognized and "priced in" other factors have had a far greater influence on both the highs and the lows in recent oil prices most from the demand side of the equation.

Thus so far there seems be no clear peak oil signal in prices its simply not there. So far only hot water.

Memmel

I think you are looking for to closely for a cause and effect relationship, Possibly peak oil is a factor in the last few bubbles as the "conventional" economy over compensated for falling net energy by allowing over zealous growth in other areas, i.e. It masked the effect simply because it could. Conventionally the "automatic stabilizers" would kick in if such a pivotal commodity such as oil was in short supply, but in oils case its own short supply (which should strangle the economy) generates growth (in attempting to extract more/economise more/substitute).

This is where conventional economics fails, it treats oil as just another product, not the crucial major contributor to all productivity.

Neven

I don't disagree what I'm trying to say is that for the most part despite the wild swing in oil prices its been BAU. I expect that as oil depletion/export land advances that we will see a strong and direct signal from peak oil. I'm asserting we have yet to see it. Put it this way the ability of expanding debt to work as faux economic growth despite tepid growth in oil supplies and changing import patters is business as usual at least since the 1970's for most of the OECD nations excluding Britain/Canada for a few decades.

I'd argue the price spike in 2008 had a lot more to do with a bit of final bubble economy blow off than with basic lack of oil. It was peak BAU. So far given the size of the bubble we have also had a fairly standard recession. Thus although this last party and resulting hangover where super sized they where not fundamentally different outside of stagnant oil production despite rising prices.

But the game is now changing. Now we are I believe starting to begin a new phase where the critical nature of oil becomes important in its own right. But to repeat myself one more time whats most important for everyone to understand is that we are almost certainly in a once in a lifetime transition period. Or probably more correct once in a civilization.

Whats happening right now is so huge it splits the next few years off as being completely different from every year thats gone before.

It could well be that what we see is just a repeat of 2008 for decades I doubt it but it still marks the end.

The next important thing to understand is that given I'm saying we are undergoing a gut wrenching economic transition where fiat money effectively no longer works we simply can't project the past into the future. New and powerful trends are developing that will swamp out the old BAU relationships. Again it could just mean we have a sort of cycle of price spikes and collapses and the economy contracts however I simply don't see that as the most likely scenario. And I just don't feel that recent price history will be a good guide to future oil pricing. I just can't see this 200 year disaster ending with a whimper.

I hadn't thought about 2008 being peak BAU, but I guess that is a reasonable description of where we are been.

This downward trend is really uncharted. In some ways, I guess what I am saying is "Don't expect that there has to be a huge price spike for oil availability to be going down. That is a simple explanation of how things may work, but we are in uncharted territory now."

Memmel,

I think both you and Gail have done a fine job of presenting your arguments.Obviously there are so many variables involved no one can say for sure what will happen in the short term,but the long term is, paraxodically, easier.

My guess is that Gail is more nearly on the money for the next year or two ,or maybe even five years or so.

But if the depletion numbers we see here on the Oil Drum are correct,(and I suppose they are as good as any and better than most)then unless the world economy continues to contract and contract fast,the depletion problem will soon out wiegh the contraction problem ,and then I'm with you.

Once the market really recognizes peak oil,the sky is the limit imo.

What's to stop a long term Warren Buffet type investor from simply tying up a good field and waiting for his windfall?

Or a megabank from moving from tank farms and parked and loaded supertankers to under ground storage of crude similar to the fed's storage of the strategic reserve?

Or the Saudi royal family deciding that crude undisturbed under the sand is a better investment than bonds and stocks?

Of course WWIII will rearrange the ownership of the world considerably,and like the big one in California, it's coming-someday.

As an amatuer student of history,my opinion is that the only thing that is stopping it is in fact fear of nuclear Armageddon.

Whats vital about my argument is to understand you simply can't take whats happened to date and speculate into even the near term future. I'd argue that the price now will have zero bearing on the price even six months from now. At best you can look into the future about three months. If you will we are right now at a sort of Black Swan moment. Now six to eight months from now I'd argue that we can begin to look farther out into the future but for now at least we can only take what happens as it comes.

I've written a few times that I think we are right in the middle of a critical transition from pre to a post peak world. But for the moment at least this completely obscures any attempt to even guess the future.

I think there is a real possibility that there will be a major break, and things will be very different going forward.

This would likely come in the form of a breakdown in international trading, many political changes, and possibly even war. My expectation that something of this form would result in a much bigger drop in oil production. I am not certain we can even talk about what it would do with prices. There may be a new price system all together.

There are all these rumors about the US sending huge amounts of $ to its embassies and consulates and telling them to change it to the local currency---they will need about a years` worth of cash apparently and they should be done with the changing within 120-150 days.

Also I read that Panasonic asked all its employees in the US to leave by September 9. Is this true or just a grim I-net rumor?

I wonder if the US govt IS planning some sort of major US$ devaluation or bank holiday in order to get out ahead of this mess and take control of the situation before it loses any possibility of doing so in the future?

Stoneleigh predicted currency controls I remember.......

Some are saying there will be a new curency, one based on something with value.

We shall see.

I don't agree with the internet rumor of either a 'de jure' devaluation or of a bank holiday.

These kinds of rumors are quite similar to rumors that have Barack Obama as not being the President because he was born in Nairobi, Kenya. Or Jakarta. Or Monrovia. There doesn't appear to be any rationale behind this bank holiday rumor.

First of all, the bank holiday would accomplish exactly what? Friday, Saturday and Sunday are more than enough time to roll over failed banks and - as during the crisis period of last year - bail out important friends of the Treasury Secretary.

And crush the competition of Goldman- Sachs and JP Morgan- Chase. Ol' JP would be proud!

When FDR declared his famous bank holiday in 1934, there was no deposit insurance; depositors were yanking funds from accounts and causing solvent banks to fail. Banks had been failing for years and the stream of failures fed on itself, becoming a river of palpable fear. The bank holiday stemmed the panic and gave Roosevelt the opportunity to ship stacks of liquid cash - by airplane - to banks all over the country.

See, "The Glory and the Dream" by William Manchester.

Today, there is the FDIC. Deposits are insured to the amount of $250k. There is no need for a holiday.

As for a devaluation; compared to what? The world's other currencies are as sorry as the dollar. Even the once- mighty Swiss franc is on the ropes as Switzerland teeters at the edge of an Eastern European credit meltdown, funded in francs. Devaluation of the dollar would simply make petroleum that much more expensive. The current slide in the dollar is already contributing to an almost 100% price rise since the beginning of the year. If the economy is staggering around now like a drunken sailor as a consequence of $60 oil, imagine what it will do with a cheaper dollar and oil prices twice as high.

Most likely are credit problems expanding from eastern Europe. In today's whacky markets this would probably mean a sharply higher Euro ... for awhile. As European bank failures multiply, the outcome as usual would be a flight to safety into the dollar and Treasuries.

I'm more cynical that the usual pundit. The Treasury simply has to push one of its zombies off the cliff and the resulting panic would punch up the dollar. Morgan- Stanley, anyone?

From reading Matthew Simmons, it didn't sound like Saudi Arabia has the luxury of sitting on their oil. They need the cash flow for infrastructure investment, debt payments, and to subsidize their rapidly growing population. How do they get from here to there (deciding to sit on their oil)?

They don't have to sit on all of it.And the way bookkeepers and accountants work sometimes seems to me to be straight out of an acid trip-although I do more or less understand why things are done the way they are done.

They sit on billions in investmenst while they borrow billions more for infrastructure or social needs.Why? Because they think the investments will repay the debt plus the interest plus leave something over,so they hang onto the investments.

In an area of rising prices they can make more on the oil in the ground than they can make in bonds or stocks-or they may think they can at least.

Oil left in the ground when it was twenty a barrel a few yars back that could be sold today or this year for anywhere from forty to eighty,or last year for a hundred plus,could easily beat most portfolios over the same period.

They can sit on some oil until they have no cash reserves or other investments left if they choose to do so.As far as I know they have plenty of both in Saudia Arabia and most of the middle east but of course the situation in Venezula and Mexico is different.

If depletion numbers are correct here on TOD...

Here on TOD they are talking about 2% to 3% depletion.

But the IEA in its latest report from November 2008 talks about 8% depletion without new discoveries and about 6.3% with new discoveries included. Thats the IEA! Did you forgot this report?

I think you are talking about decline rates, and you are right there are all kinds of numbers around, in different reports, depending on what is referred to. The IEA has post peak decline rates, and post plateau decline rates. Overall decline rates, which include increasing as well as decreasing fields, but not new production, are often quoted at about 4.5%.

I don't know what you are referring to by "Here on TOD they are talking about 2% to 3% depletion?" Are you talking about Ace's graph? On it, he is adding new production. In addition to that, Ace's number include both fields where production was recently started, which are increasing, and fields where production is now decreasing. It is not surprising to me that this number (including new fields, fields with increasing production, and fields with decreasing production) would show a much smaller decline rate than the 8% IEA was talking about, based on only fields in decline. I am also not surprised that it is lower than an overall decline rate of 4.5%, not including new production.

It is sort of apples, oranges, and pears.

Yes, you need a discovery model plus a reserve growth model to compensate for depletion. This allows you to arrive at an aggregate.

It may be apples ad oranges to a certain extent yet these growth and depletion terms can be easily mixed using the shock model. Nothing I have seen suggests that there is any fundamental problem in the understanding. Depletion, decline, growth all have the same dimensional units if treated correctly.

There has been research on what percentage oil costs can be, relative to GDP, before there start to be recessionary impacts. I was hoping that one of these posts would be up before this post, but I don't remember one. We will likely have one shortly. The maximum oil price before there are recessionary impacts seems to be in the 4% to 8% range, and this has a limiting impact on oil prices. (It is different for US and world, and imports affect this result.)

The problem is that as oil prices rise, so do substitutes, and so do food prices. The prices of use goods that are shipped by oil rises. Demand for all of these things is relatively inelastic, so it is demand for the elastic goods that is cut back (new houses, new cars, trips to restaurants). All of this puts a brake on the economy, and tends to hold prices down.

Gail,

Surely Euan's post on the financial return on energy invested suggested <14% of GDP for energy was a critical value.

http://europe.theoildrum.com/node/5495#more

It's important not to forget that these numbers are not set in concrete, as the economy changes a very different number could be sustainable.

Long term declines in electricity and NG will provide more room for oil to take up a larger portion of total energy.

This says nothing about oil price long term, for example a 100% increase in efficiency of oil used could allow a 100% rise in price with no change in % of economy. Or for example if 50% of vehicles moved to EV, and the other 50% ICE vehicles had twice the fuel economy(HEV), gasoline use could be only 25% of today's figure and the price 400% higher. Other sectors such as heating oil and jet fuel may be forced out and completely replaced.

Thanks for reminding me of that link. Euan's analysis is of total energy, rather than oil, which would be lower, and would to some extent depend on other energy availability / cost.

There have been other posts as well. This is one by Dave Murphy, specifically looking at oil. His cut-off for recession is about 5.5% for oil.

Memmel,

When do you expect the market to "price in" Peak Oil?

The thing that has begun to strike me is the extent to which the "market", by that I mean, the "traders" understand the nature of the Peak Oil problem. In today's "Energy Bulletin" there was an interview with Marshall Adkins of Raymond James Assoc. in which he very succinctly discusses Peak Oil and most interestingly, the lack of counter-argument he has been getting from the investment community. We also have the likes of Matt Simmons, long term member of the oil patch's investment banking community as well as people like Morgan Downey who wrote "Oil 101" and a trader in oil commodities for fifteen years. None of these people are "fringe elements". It seems to me that at this point, a sizable segment of the oil business/trading community is pretty well up to speed on the Peak Oil problem. It seems to me that it's now more the mainstream media and politicians who still don't "get it".

I am watching market sentiment very closely at the Energy Futures Databrowser.

Here is the crude oil futures chain from yesterday (which basically means from Friday's close):

The black dots are yesterday's futures chain. The red dots are futures chains from each day of the last week. Blue is from the last month and gray is from the most recent quarter.

If you aren't used to looking at this data, the first and most astonishing thing is that traders are willing to place bets on the dollar price of oil all the way out to December of 2017!!!

More to the point of Jabberwock's comment, in the last month we can see a range of prices and, more importantly, a steepening contango. ( This means that contracts for delivery out in the distant future are more expensive than contracts for delivery in the near future.) I take this to mean that traders are betting either on inflation or on oil scarcity or both.

(Personally, I believe they are vastly underestimating the potential for both in the 10-year time frame.)

It will be interesting to see what will happen to the shape of the curve if there is another big leg down in the stock market.

Happy Exploring!

-- Jon

This is also for Jabberwock.

However I think right now the bulk of the contango is inflation fears and I agree even these are probably understated if commodities are simply constrained.

I also look at this sort of signature on a daily basis. Its the futures chain that matters in my opinion for peak oil.

I think once it really hits we will see one of two types of events occur. Either the front month will go into steep backwardation literally snapping the futures chain towards some new ridiculous number say 500 a barrel.

This would happen fast i.e the front month would go in a sort of tight spiral with the futures rising then forcing up the futures.

Or we will see a camel hump develop in the further out futures starting 3-6 months out this will then lift both the front and future contracts. you would have contango before the camels up and backwardation afterwards.

The 3-6 month area is about as far out as real oil users use the futures market to any large degree past that its generally pure speculation. Thats not to say its not commercial player even further out but they are also speculating much past six months.

My bet is on a camels hump.